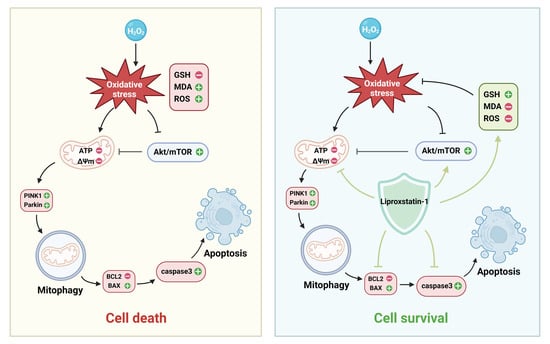

Liproxstatin-1 Protects SH-SY5Y Cells by Inhibiting H2O2-Induced Excessive Mitophagy and Apoptosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

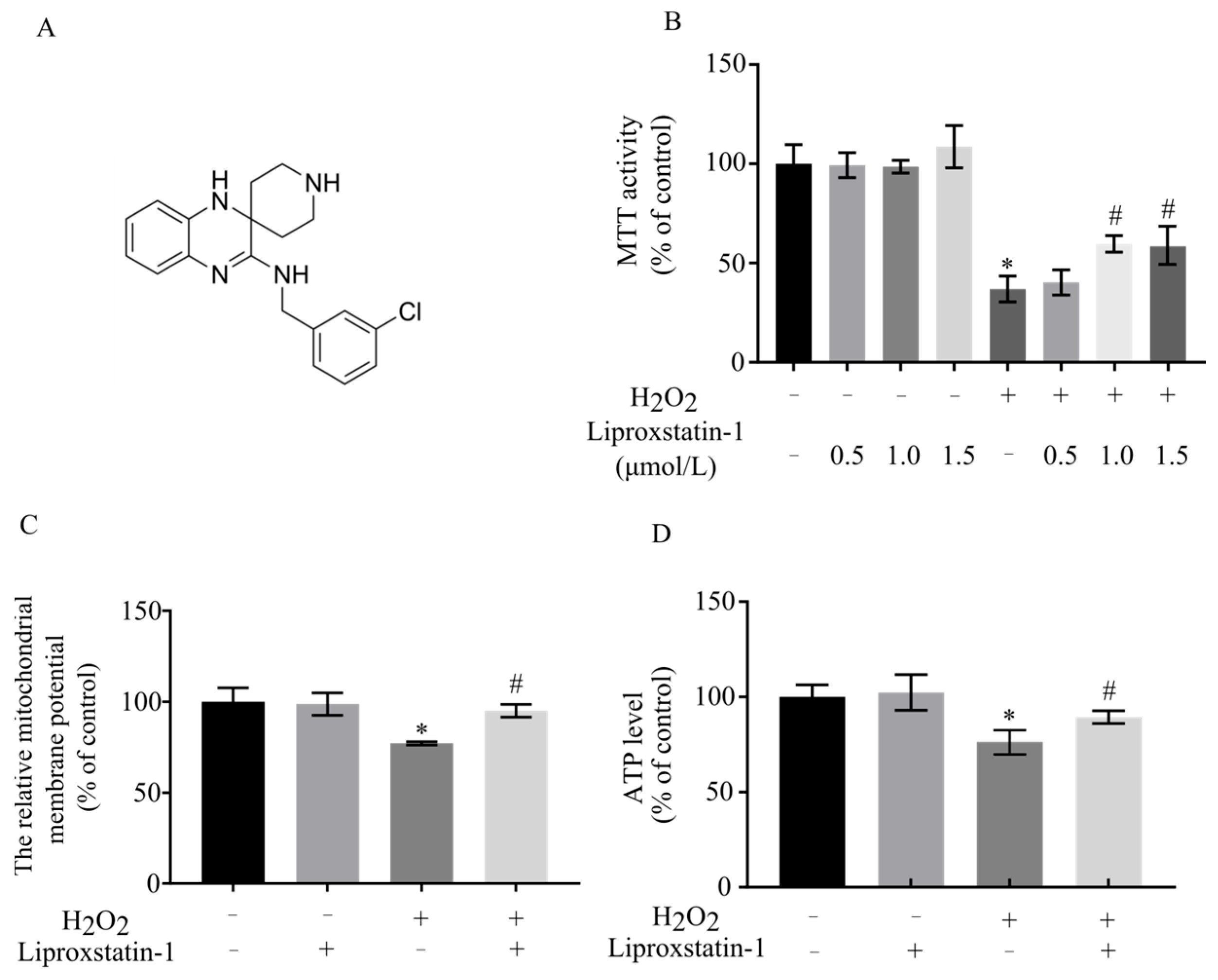

2.1. Liproxstatin-1 Preserves Cell Viability and Mitochondrial Function in H2O2-Exposed SH-SY5Y Cells

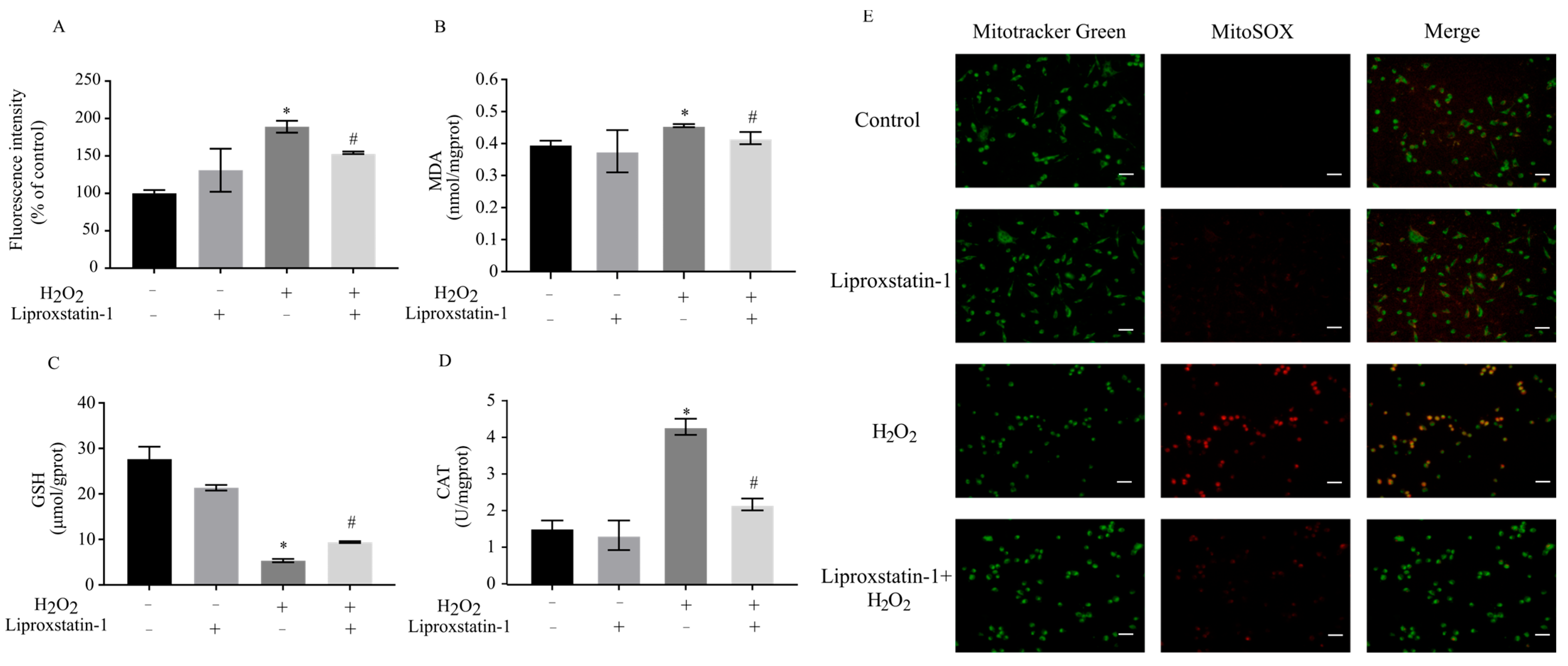

2.2. Liproxstatin-1 Attenuates Oxidative Stress in H2O2-Treated SH-SY5Y Cells

2.3. Liproxstatin-1 Modulates Mitophagy and Mitophagy-Related Protein Expression in H2O2-Treated SH-SY5Y Cells

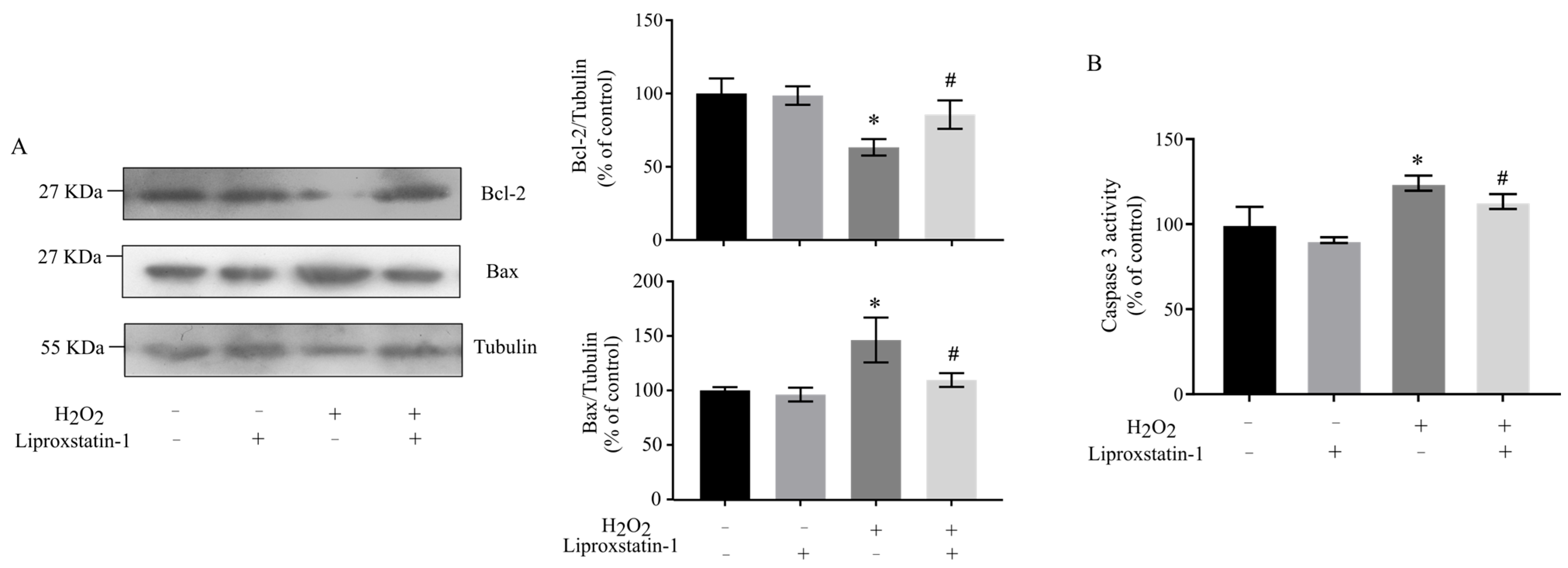

2.4. Liproxstatin-1 Attenuates H2O2-Induced Apoptosis in SH-SY5Y Cells via Regulation of Mitochondrial Pathways

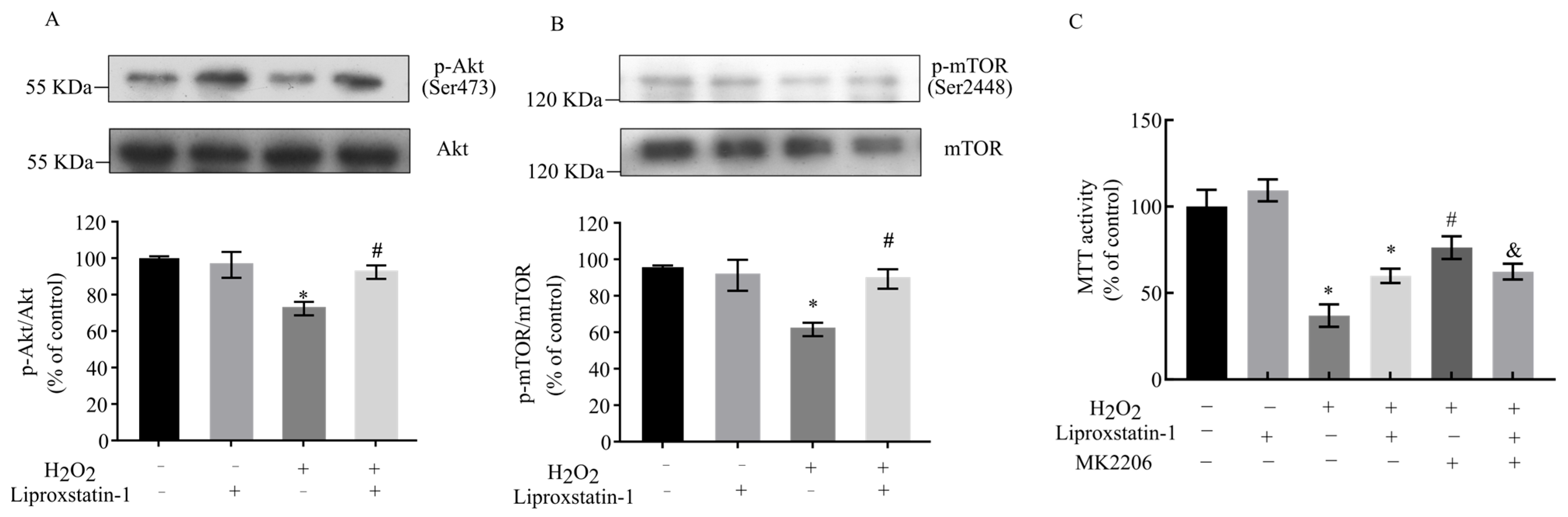

2.5. Liproxstatin-1 Preserves Akt/mTOR Signaling in H2O2-Exposed SH-SY5Y Cells

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Cell Culture

4.3. MTT Assay

4.4. Measurement of ATP Content

4.5. Measurement of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential

4.6. Measurements of Total ROS and Mitochondrial ROS

4.7. Measurement of Caspase 3 Activity

4.8. Measurement of MDA

4.9. Measurement of GSH

4.10. Measurement of CAT

4.11. Mitochondria and Lysosomes Colocalization

4.12. Analyses of Mitochondrial Mass

4.13. Western Blot Assays

4.14. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Wanderoy, S.; Hees, J.T.; Klesse, R.; Edlich, F.; Harbauer, A.B. Kill one or kill the many: Interplay between mitophagy and apoptosis. Biol. Chem. 2020, 402, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fields, M.; Marcuzzi, A.; Gonelli, A.; Celeghini, C.; Maximova, N.; Rimondi, E. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants, an innovative class of antioxidant compounds for neurodegenerative diseases: Perspectives and limitations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, R.G.; Hollville, E.; Martin, S.J. Parkin sensitizes toward apoptosis induced by mitochondrial depolarization through promoting degradation of Mcl-1. Cell Rep. 2014, 9, 1538–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lossi, L. The concept of intrinsic versus extrinsic apoptosis. Biochem. J. 2022, 479, 357–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayersdorf, R.; Schumacher, B. Recent advances in understanding the mechanisms determining longevity. F1000Research 2019, 8, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, T.; Li, M.; Lin, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tang, S.; Dai, C. Ivermectin-induced apoptotic cell death in human SH-SY5Y cells involves the activation of oxidative stress and mitochondrial pathway and Akt/mTOR-pathway-mediated autophagy. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Q.; Liu, H.; Yang, C.; Chen, Y.; Huang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Pan, Y.; He, J.; Du, Q.; Wang, Q.; et al. Bushen-Yizhi formula exerts neuroprotective effect via inhibiting excessive mitophagy in rats with chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 310, 116326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, J.; Lan, X.T.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Sun, D.-Y.; Wang, X.-J.; Ou-Yang, S.-X.; Zhuang, C.-L.; Shen, F.-M.; Wang, P.; et al. Ferroptosis inhibitor liproxstatin-1 alleviates metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease in mice: Potential involvement of PANoptosis. ACTA Pharmacol. Sin. 2023, 44, 1014–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, M.; Cao, F.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, H.; Cao, J.; Song, J.; Ma, Y.; Mi, W.; et al. The ferroptosis inhibitor liproxstatin-1 ameliorates LPS-induced cognitive impairment in mice. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Li, Y.; He, C.; Yan, F.; Li, J.R.; Xu, H.Z.; Zhuang, J.F.; Zhou, H.; Peng, Y.C.; Fu, X.J.; et al. Selective ferroptosis inhibitor liproxstatin-1 attenuates neurological deficits and neuroinflammation after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosci. Bull. 2021, 37, 535–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.Y.; Pang, Y.L.; Li, W.X.; Zhao, C.-X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Ning, G.-Z.; Kong, X.-H.; Liu, C.; Yao, X.; et al. Liproxstatin-1 is an effective inhibitor of oligodendrocyte ferroptosis induced by inhibition of glutathione peroxidase 4. Neural Regen. Res. 2021, 16, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Ding, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, F.; Zhang, G.; Zheng, X.; Jia, G.; et al. Astaxanthin Inhibits H2O2-Induced Excessive Mitophagy and Apoptosis in SH-SY5Y Cells by Regulation of Akt/mTOR Activation. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Fan, Y.; Yu, Y.; Loor, J.J.; Elsabagh, M.; Peng, A.; Wang, H. L-arginine alleviates hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative damage in ovine intestinal epithelial cells by regulating apoptosis, mitochondrial function, and autophagy. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 1038–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Bae, J.Y.; Yoo, S.; Kim, H.W.; Lee, S.A.; Kim, E.T.; Koh, G. 2-Deoxy-d-ribose induces ferroptosis in renal tubular epithelial cells via ubiquitin-proteasome system-mediated xCT protein degradation. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2023, 208, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, P.; Sun, Z.; Gou, F.; Wang, J.; Fan, Q.; Zhao, D.; Yang, L. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial impairment: Key drivers in neurodegenerative disorders. Ageing Res. Rev. 2025, 104, 102667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Yin, W.; Wang, J.; Feng, L.; Kang, Y.J. Mitophagy promotes the stemness of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Exp. Biol. Med. 2020, 246, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, H.Q.; Liang, S.J.; Xu, Y.L.; Dai, Y.; Sun, N.; Deng, D.H.; Cheng, P. Liproxstatin-1 induces cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and caspase-3/GSDME-dependent secondary pyroptosis in K562 cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2022, 61, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galber, C.; Minervini, G.; Cannino, G.; Boldrin, F.; Petronilli, V.; Tosatto, S.; Lippe, G.; Giorgio, V. The f subunit of human ATP synthase is essential for normal mitochondrial morphology and permeability transition. Cell Rep. 2021, 35, 109111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Shi, R.; Wang, S.; Duan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, P.; Sun, X.; Chen, X.; Ji, G.; Shen, Y.; et al. ADSL promotes autophagy and tumor growth through fumarate-mediated Beclin1 dimethylation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2025, 21, 894–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad-Jiménez, Z.; López-Domènech, S.; Pelechá, M.; Perea-Galera, L.; Rovira-Llopis, S.; Bañuls, C.; Blas-García, A.; Apostolova, N.; Morillas, C.; Víctor, V.M.; et al. Calorie restriction modulates mitochondrial dynamics and autophagy in leukocytes of patients with obesity. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 225, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiney, S.J.; Adlard, P.A.; Lei, P.; Mawal, C.H.; Bush, A.I.; Finkelstein, D.I.; Ayton, S. Fibrillar alpha-synuclein toxicity depends on functional lysosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 17497–17513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, A.; Yoshikawa, S.; Ikeda, Y.; Taniguchi, K.; Sawamura, H.; Morikawa, S.; Nakashima, M.; Asai, T.; Matsuda, S. Tactics with prebiotics for the treatment of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease via the improvement of mitophagy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Yap, Y.Q.; Moujalled, D.M.; Sumardy, F.; Khakham, Y.; Georgiou, A.; Jahja, M.; Lew, T.E.; De Silva, M.; Luo, M.X.; et al. Differential regulation of BAX and BAK apoptotic activity revealed by small molecules. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadr8146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.C.; Chen, Y.T.; Liu, H.W.; Chan, Y.-C.; Liu, M.-Y.; Hu, S.-H.; Tseng, W.-T.; Wu, H.-L.; Wang, M.-F.; Chang, S.-J. Oligonol alleviates sarcopenia by regulation of signaling pathways involved in protein turnover and mitochondrial quality. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2019, 63, 1801102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhuang, H.; Wen, X.; Su, Y.; Wang, J.; Qin, H.; Wang, J.; Shangguan, Z.; Ma, Y.; Dong, J.; et al. Organelle remodeling enhances mitochondrial ATP disruption for blocking neuro-pain signaling in bone tumor therapy. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 506, 159825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mock, J.T.; Mensah-Kane, P.; Davis, D.L.; Wong, J.M.; Vann, P.H.; Forster, M.J.; Sumien, N. Lifelong glutathione deficiency in mice increased lifespan and delayed age-related motor declines. Aging Dis. 2025, 16, 3671–3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Lu, Y.; Long, C.; Song, Y.; Dai, Q.; Hou, J.; Wu, J.; Lin, H.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, D. Interaction mechanism of lipid metabolism remodeling, oxidative stress, and immune response mediated by Epinephelus coioides SRECII. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2025, 228, 14–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, X.W.; Bhave, M.; Fong, A.Y.Y.; Matsuura, E.; Kobayashi, K.; Shen, L.H.; Hwang, S.S. Cytoprotective and cytotoxic effects of rice bran extracts in rat H9c2(2-1) cardiomyocytes. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 6943053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakash, R.; Fauzia, E.; Siddiqui, A.J.; Yadav, S.K.; Kumari, N.; Singhai, A.; Khan, M.A.; Janowski, M.; Bhutia, S.K.; Raza, S.S. Oxidative stress enhances autophagy-mediated death of stem cells through Erk1/2 signaling pathway—Implications for neurotransplantations. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2021, 17, 2347–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Liu, S.; Li, J.; Tian, Y.; Xue, Y.; Liu, X. Parkin and Nrf2 prevent oxidative stress-induced apoptosis in intervertebral endplate chondrocytes via inducing mitophagy and anti-oxidant defenses. Life Sci. 2020, 243, 117244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel-Lerma, L.E.; Carrillo-Campos, J.; Sianez-Estrada, L.I.; Siqueiros-Cendon, T.S.; Leon-Flores, D.B.; Espinoza-Sanchez, E.A.; Arevalo-Gallegos, S.; Iglesias-Figueroa, B.F.; Rascon-Cruz, Q. Molecular docking of lactoferrin with apoptosis-related proteins insights into its anticancer mechanism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, C.Y.; Liu, S.W.; Chen, C.J.; Chen, W.Y. Chlorpyrifos induces apoptosis in macrophages by activating both intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways. Environ. Toxicol. 2025, 40, 1150–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Nam, S.A.; Koh, E.S.; Kim, H.W.; Kim, S.; Woo, J.J.; Kim, Y.K. The impairment of endothelial autophagy accelerates renal senescence by ferroptosis and NLRP3 inflammasome signaling pathways with the disruption of endothelial barrier. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Wang, H.; Yan, L.; Han, X. Isoegomaketone improves radiotherapy efficacy and intestinal injury by regulating apoptosis, autophagy and PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling in a colon cancer model. Oncol. Rep. 2025, 53, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Ozgen, S.; Luo, H.; Krigman, J.; Zhao, Y.; Xin, G.; Sun, N. The mitochondrial deubiquitinase USP30 regulates AKT/mTOR signaling. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 816551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Wang, L.; Lv, H.; Liu, J.; Dong, Y.; Shi, L.; Ji, Q. EphA2 inhibits SRA01/04 cells apoptosis by suppressing autophagy via activating PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2021, 711, 109024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Wang, J.; Liu, M.; Chen, G. Fluvastatin protects neuronal cells from hydrogen peroxide-induced toxicity with decreasing oxidative damage and increasing PI3K/Akt/mTOR signalling. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2021, 73, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; Ares, I.; Martínez, M.; Lopez-Torres, B.; Martínez-Larrañaga, M.-R.; Wang, X.; Anadón, A.; Martinez, M.-A. Neonicotinoids: Mechanisms of systemic toxicity based on oxidative stress-mitochondrial damage. Arch. Toxicol. 2022, 96, 1493–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpellini, C.; Klejborowska, G.; Lanthier, C.; Hassannia, B.; Vanden Berghe, T.; Augustyns, K. Beyond ferrostatin-1: A comprehensive review of ferroptosis inhibitors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 44, 902–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Du, Y.; Zheng, J.; Tang, W.; Liang, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Liu, B.; Sun, H.; Wang, K.; Shao, C. Liproxstatin-1 alleviated ischemia/reperfusion-induced acute kidney injury via inhibiting ferroptosis. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.; Liu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, L.; Cheng, J.; Hua, R.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Q. Melatonin protects mouse testes from palmitic acid-induced lipotoxicity by attenuating oxidative stress and DNA damage in a SIRT1-dependent manner. J. Pineal Res. 2020, 69, e12690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Sun, F.; Xiong, B.; Zhang, Z. Preparation of mitochondria to measure superoxide flashes in angiosperm flowers. PeerJ 2019, 7, e6708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, D.H.; Kim, G.H.; Nepal, R.U.; Nepal, M.R.; Jeong, T.C. A convenient spectrophotometric test for screening skin-sensitizing chemicals using reactivity with glutathione in chemico. Toxicol. Res. 2024, 40, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, C.; Guo, Y.; Li, J.; Wu, C.; Jiao, J.; Zheng, H. Ginsenoside Rg1 improves Alzheimer’s disease by regulating oxidative stress, apoptosis, and neuroinflammation through Wnt/GSK-3β/β-catenin signaling pathway. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2022, 99, 884–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalta, J.I.; Galli, S.; Iacaruso, M.F.; Antico Arciuch, V.G.; Poderoso, J.J.; Jares-Erijman, E.A.; Pietrasanta, L.I. New algorithm to determine true colocalization in combination with image restoration and time-lapse confocal microscopy to MAP kinases in mitochondria. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, T.; Ding, F.; Fang, Z.; Zhao, Y. Liproxstatin-1 Protects SH-SY5Y Cells by Inhibiting H2O2-Induced Excessive Mitophagy and Apoptosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11641. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311641

Yan T, Ding F, Fang Z, Zhao Y. Liproxstatin-1 Protects SH-SY5Y Cells by Inhibiting H2O2-Induced Excessive Mitophagy and Apoptosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11641. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311641

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Tingting, Feng Ding, Zhongyuan Fang, and Yan Zhao. 2025. "Liproxstatin-1 Protects SH-SY5Y Cells by Inhibiting H2O2-Induced Excessive Mitophagy and Apoptosis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11641. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311641

APA StyleYan, T., Ding, F., Fang, Z., & Zhao, Y. (2025). Liproxstatin-1 Protects SH-SY5Y Cells by Inhibiting H2O2-Induced Excessive Mitophagy and Apoptosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11641. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311641