Antibody-Dependent Cytotoxicity of Monocytes in Preeclampsia Is Associated with Soluble Forms of HLA

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Clinical Characteristics of Patients

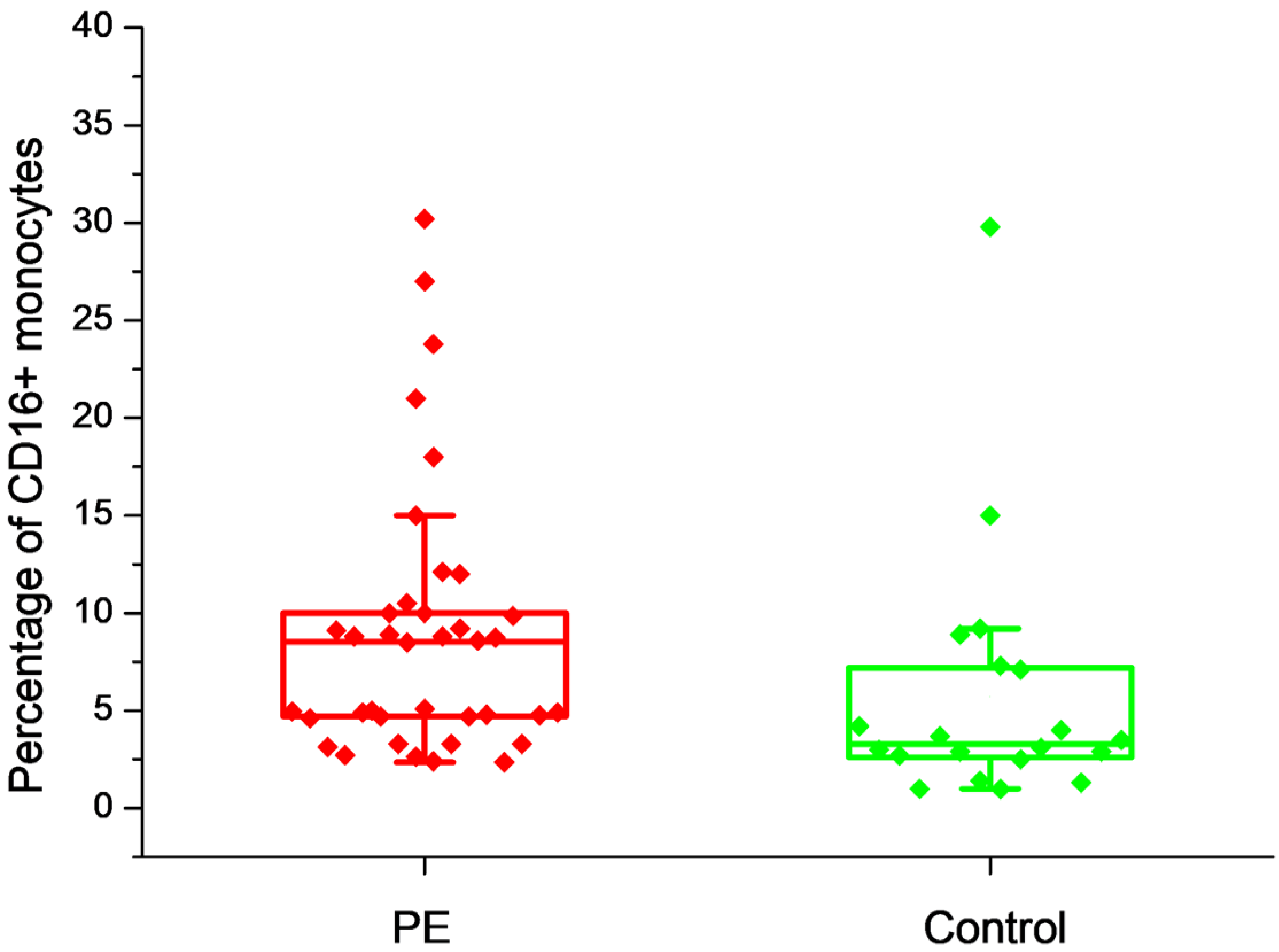

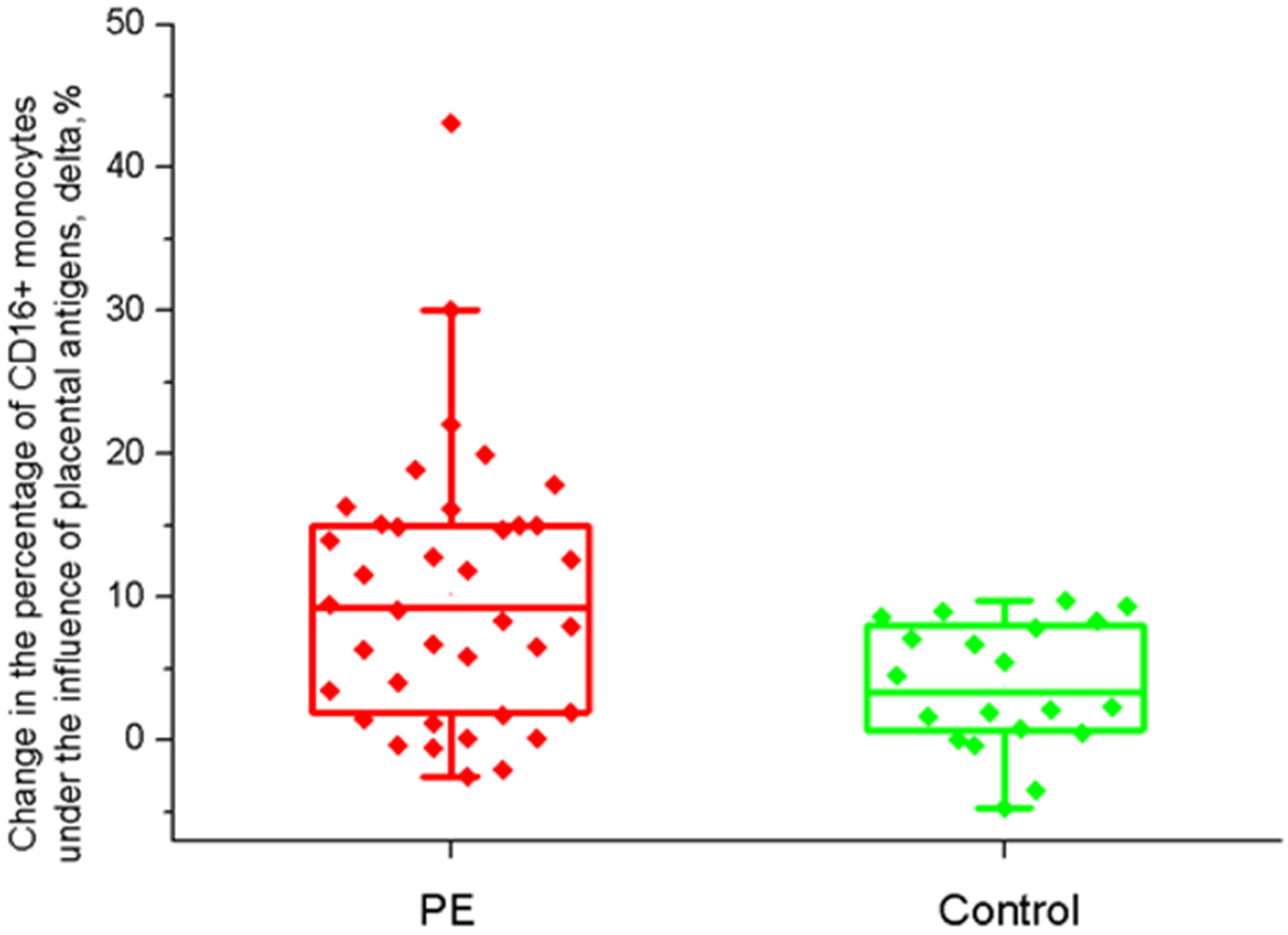

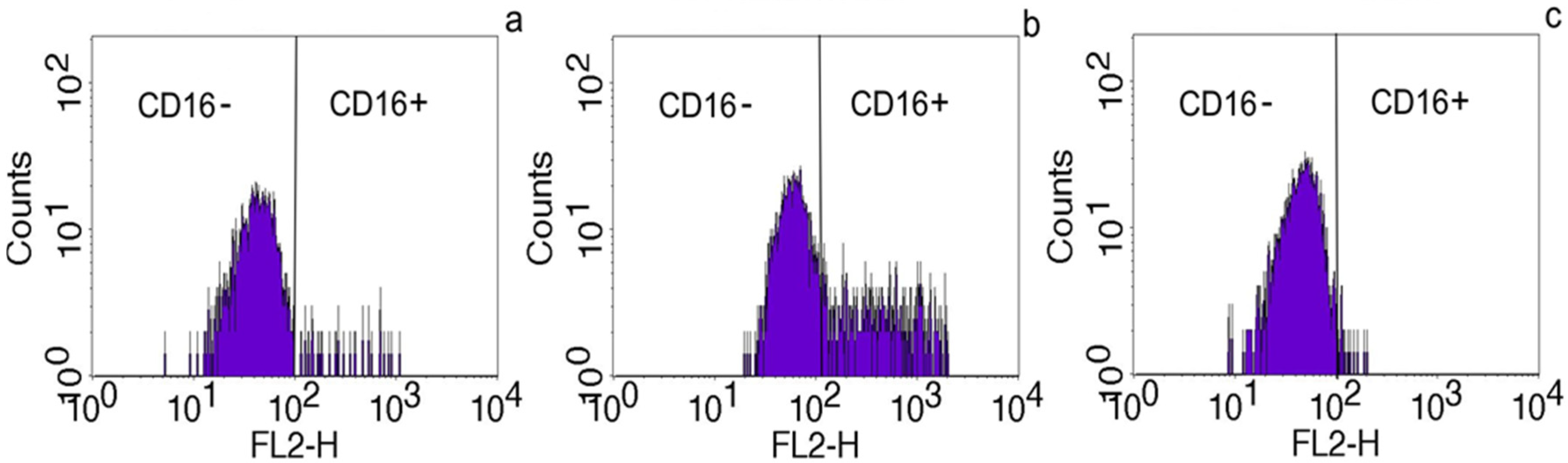

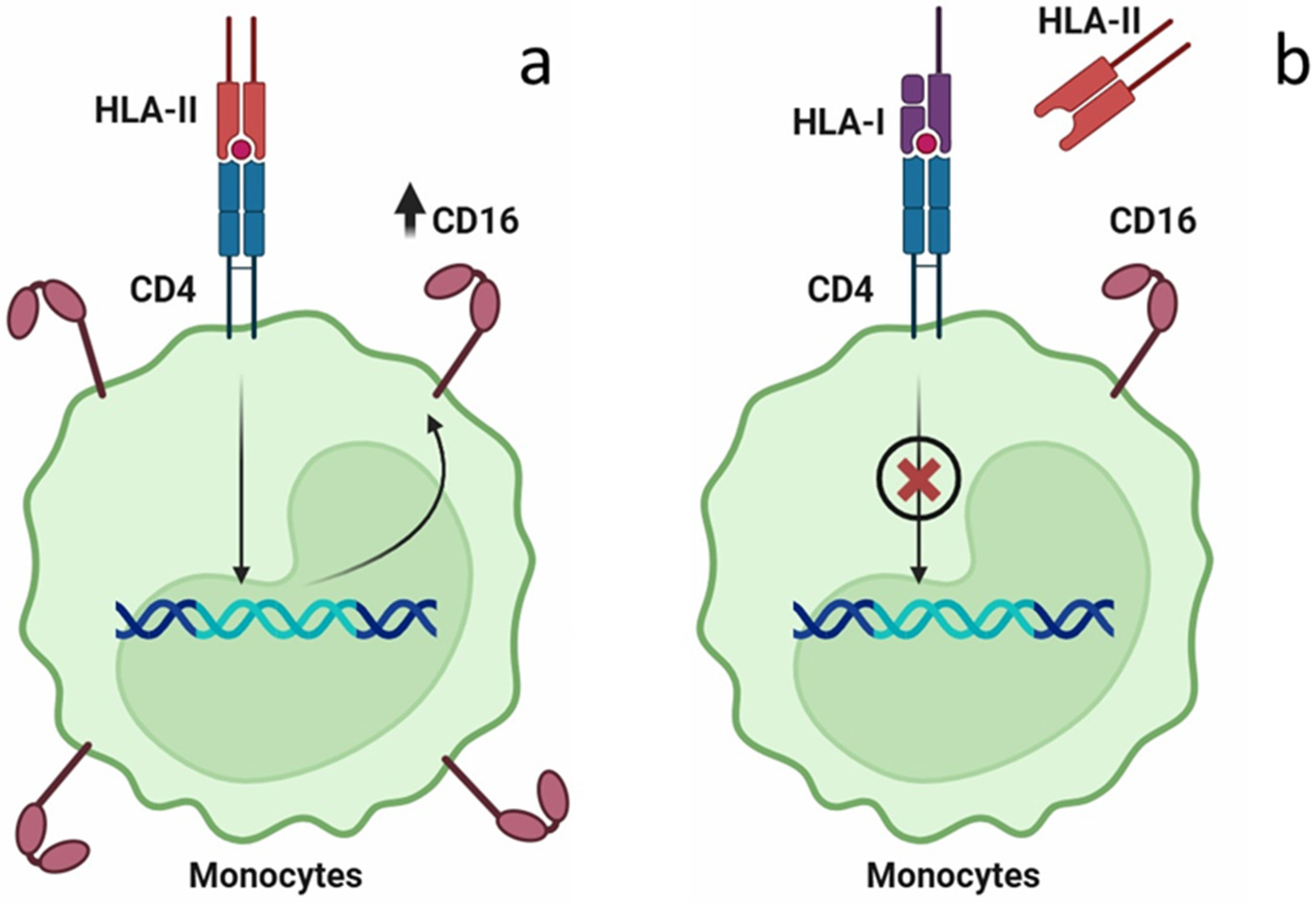

2.2. The Effect of Placental Soluble Factors on CD16 Expression by Monocytes

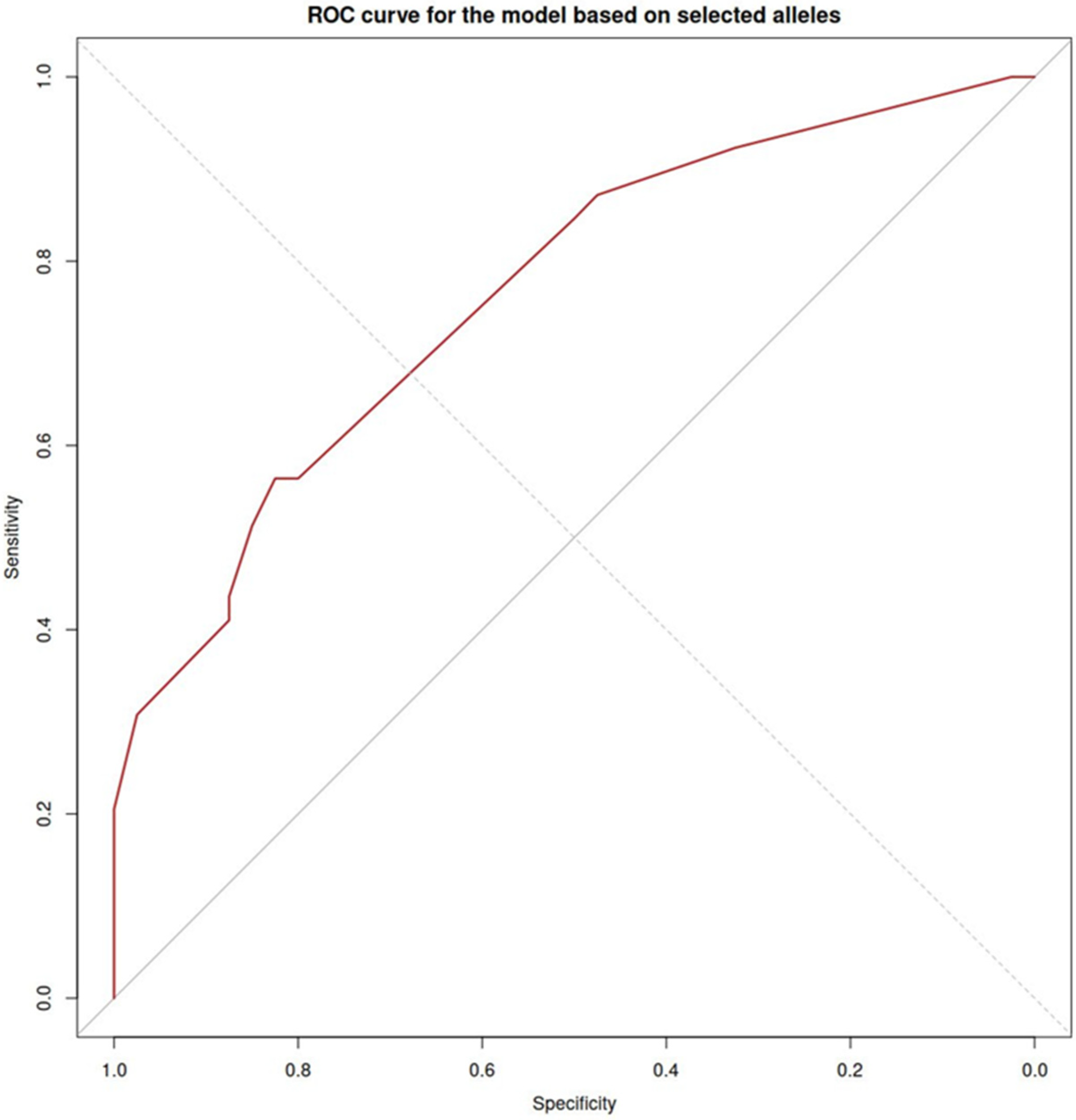

2.3. The Effect of HLA Class I (HLA-B) on CD16 Expression on Monocytes

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PE | Preeclampsia |

| OD | Oocyte donation |

| HLA | Human Leukocyte Antigens |

| ADCC | Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity |

| PVCM | Placental villus-conditioned culture medium |

| PBMC | Peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| ICM | ImmunoCult medium |

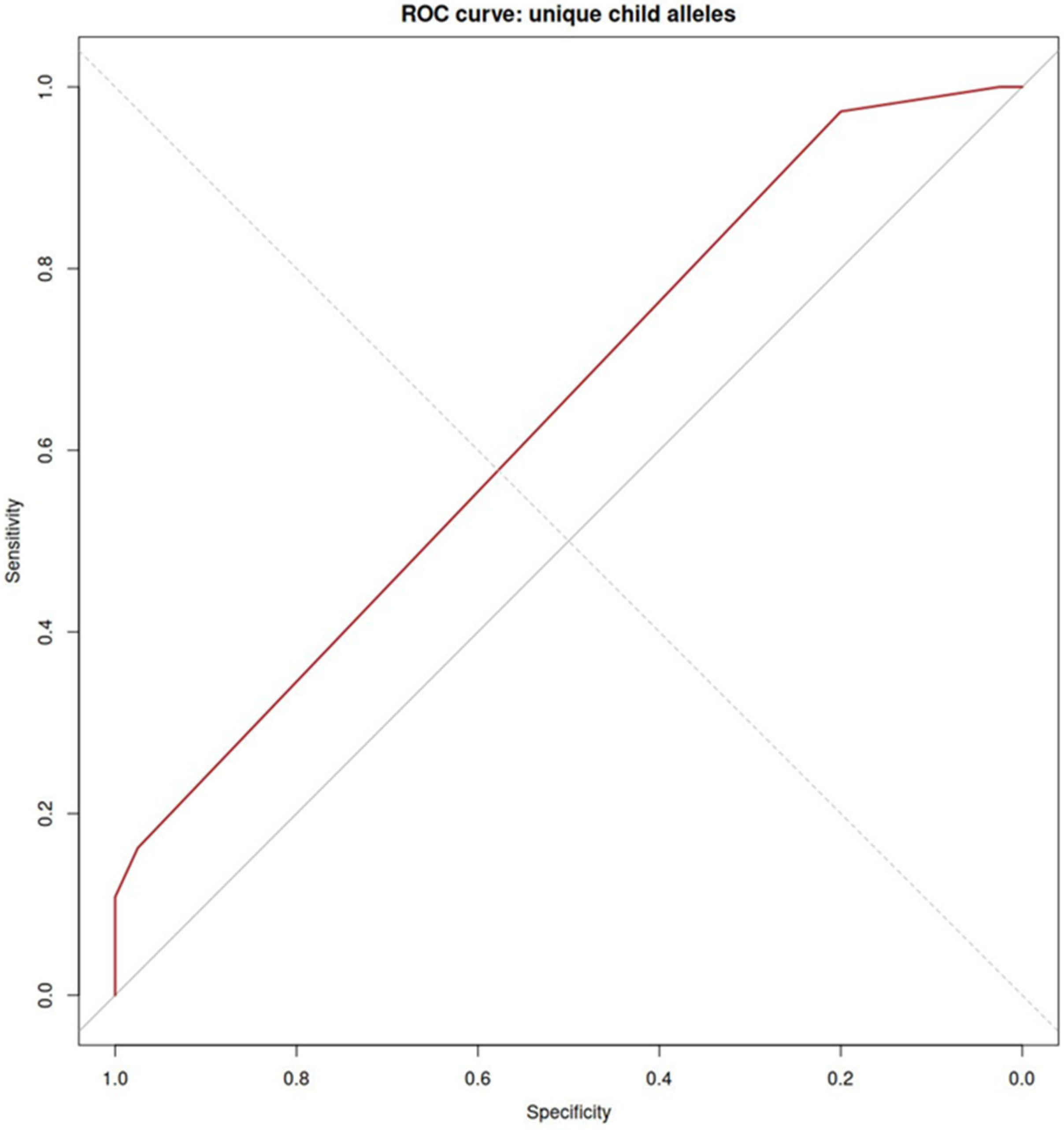

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

References

- Chappell, L.C.; Cluver, C.A.; Kingdom, J.; Tong, S. Pre-Eclampsia. Lancet 2021, 398, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, E.; Romero, R.; Yeo, L.; Gomez-Lopez, N.; Chaemsaithong, P.; Jaovisidha, A.; Gotsch, F.; Erez, O. The Etiology of Preeclampsia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 226, S844–S866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Han, T.; Zhu, X. Role of Maternal–Fetal Immune Tolerance in the Establishment and Maintenance of Pregnancy. Chin. Med. J. 2024, 137, 1399–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Varea, A.; Pellicer, B.; Perales-Marín, A.; Pellicer, A. Relationship between Maternal Immunological Response during Pregnancy and Onset of Preeclampsia. J. Immunol. Res. 2014, 2014, 210241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Bentem, K.; Bos, M.; Van Der Keur, C.; Brand-Schaaf, S.H.; Haasnoot, G.W.; Roelen, D.L.; Eikmans, M.; Heidt, S.; Claas, F.H.J.; Lashley, E.E.L.O.; et al. The Development of Preeclampsia in Oocyte Donation Pregnancies Is Related to the Number of Fetal-Maternal HLA Class II Mismatches. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2020, 137, 103074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ordikhani, F.; Pothula, V.; Sanchez-Tarjuelo, R.; Jordan, S.; Ochando, J. Macrophages in Organ Transplantation. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 582939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhen, A.; Krutzik, S.R.; Levin, B.R.; Kasparian, S.; Zack, J.A.; Kitchen, S.G. CD4 Ligation on Human Blood Monocytes Triggers Macrophage Differentiation and Enhances HIV Infection. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 9934–9946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakela, K.; Athanassakis, I. Soluble Major Histocompatibility Complex Molecules in Immune Regulation: Highlighting Class II Antigens. Immunology 2018, 153, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Van Den Bosch, T.P.; Caliskan, K.; Kraaij, M.D.; Constantinescu, A.A.; Manintveld, O.C.; Leenen, P.J.; Von Der Thüsen, J.H.; Clahsen-Van Groningen, M.C.; Baan, C.C.; Rowshani, A.T. CD16+ Monocytes and Skewed Macrophage Polarization toward M2 Type Hallmark Heart Transplant Acute Cellular Rejection. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vereyken, E.J.; Kraaij, M.D.; Baan, C.C.; Rezaee, F.; Weimar, W.; Wood, K.J.; Leenen, P.J.; Rowshani, A.T. A Shift Towards Pro-Inflammatory CD16+ Monocyte Subsets with Preserved Cytokine Production Potential After Kidney Transplantation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeap, W.H.; Wong, K.L.; Shimasaki, N.; Teo, E.C.Y.; Quek, J.K.S.; Yong, H.X.; Diong, C.P.; Bertoletti, A.; Linn, Y.C.; Wong, S.C. CD16 Is Indispensable for Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity by Human Monocytes. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34310, Erratum in Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laresgoiti-Servitje, E. A Leading Role for the Immune System in the Pathophysiology of Preeclampsia. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2013, 94, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boris, D.A.; Volgina, N.E.; Krasnyi, A.M.; Tyutyunnik, V.L.; Kan, N.E. Prediction of Preeclampsia on the Couts of CD-16 Negative Monocytes. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 7, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, X.; Xu, Z.; Ren, H. Analysis of Risk Factors of Preeclampsia in Pregnant Women with Chronic Hypertension and Its Impact on Pregnancy Outcomes. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safar, M.E.; Asmar, R.; Benetos, A.; Blacher, J.; Boutouyrie, P.; Lacolley, P.; Laurent, S.; London, G.; Pannier, B.; Protogerou, A.; et al. Interaction between Hypertension and Arterial Stiffness. Hypertension 2018, 72, 796–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phipps, E.A.; Thadhani, R.; Benzing, T.; Karumanchi, S.A. Pre-Eclampsia: Pathogenesis, Novel Diagnostics and Therapies. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2019, 15, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmery, J.; Hachmon, R.; Pyo, C.W.; Nelson, W.C.; Geraghty, D.E.; Andersen, A.M.N.; Melbye, M.; Hviid, T.V.F. Maternal and Fetal Human Leukocyte Antigen Class Ia and II Alleles in Severe Preeclampsia and Eclampsia. Genes Immun. 2016, 17, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Torres, J.; Espino-Y-Sosa, S.; Martínez-Portilla, R.; Borboa-Olivares, H.; Estrada-Gutierrez, G.; Acevedo-Gallegos, S.; Ruiz-Ramirez, E.; Velasco-Espin, M.; Cerda-Flores, P.; Ramírez-González, A.; et al. A Narrative Review on the Pathophysiology of Preeclampsia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashley, E.E.L.O.; Meuleman, T.; Claas, F.H.J. Beneficial or Harmful Effect of Antipaternal Human Leukocyte Antibodies on Pregnancy Outcome? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2013, 70, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Women with PE (n = 38) | Healthy Women (n = 40) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 33.0 (29.5; 34.5) | 30.5 (29.0; 34.0) | 0.098 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29.0 (24.0; 32.0) | 25.5 (23.7; 28.2) | 0.062 |

| Primigravida | 17 (43.6) | 17 (42.5) | 0.922 |

| Primipara | 20 (51.3) | 20 (50.0) | 0.909 |

| Preeclampsia in the anamnesis | 5 (12.8) | 0 | 0.026 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 145.0 (140.0; 153.5) | 115.0 (110.1; 120.5) | 0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 90 (86; 100) | 70 (60; 75) | 0.001 |

| Protein in urine, g/L | 0.77 (0.30; 1.65) | 0.05 (0.03; 0.12) | <0.001 |

| Edema | 17 (43.6) | 6 (15.0) | 0.01 |

| Chronic arterial hypertension | 12 (30.8) | 1 (2.5) | <0.001 |

| Chronic liver disease | 12 (30.8) | 6 (15.0) | 0.093 |

| Vascular disease | 4 (10.3) | 6 (15.0) | 0.737 |

| Diabetes | 1 (2.6) | 0 | 0.494 |

| Gestational age at delivery, weeks | 35.7 (31.0; 39.0) | 39.0 (39.0; 40.0) | <0.001 |

| Cesarean section | |||

| 19 (50.0) | 6 (15.0) | <0.001 |

| 13 (34.2) | 13 (34.2) | 0.005 |

| Newborn weight, g | 2265.5 (1420.0; 3390.0) | 3367.0 (3142.5; 3685.0) | <0.001 |

| Fetal growth restriction | 8 (21.1) | 0 | 0.002 |

| Allele | Preeclampsia (n = 38) | Control (n = 40) | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | F (%) | n | F (%) | ||

| DRB1*01:01:01G | 12 | 30.8 | 1 | 2.5 | <0.001 |

| DQB1*05:01:01G | 13 | 33.3 | 4 | 10 | 0.014 |

| DPB1*04:01:01G | 22 | 56.4 | 33 | 82.5 | 0.015 |

| DRB4*01:01:01G | 11 | 28.2 | 22 | 55 | 0.022 |

| DQA1*03:01:01G | 5 | 12.8 | 14 | 35 | 0.034 |

| Allele | Preeclampsia (n = 36) | Control (n = 40) | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | F (%) | n | F (%) | ||

| DQB1*06:03:01G | 1 | 2.8 | 8 | 20 | 0.029 |

| DRB1*04:01:01G | 4 | 11.1 | 0 | 0 | 0.049 |

| DQB1*03:02:01G | 6 | 16.7 | 1 | 2.5 | 0.051 |

| DRB1*13:01:01G | 1 | 2.8 | 7 | 17.5 | 0.058 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krasnyi, A.M.; Sorokina, L.E.; Argentova-Stevens, A.M.; Kokoeva, D.N.; Alekseev, A.A.; Jankevic, T.; Kan, N.E.; Tyutyunnik, V.L.; Sukhikh, G.T. Antibody-Dependent Cytotoxicity of Monocytes in Preeclampsia Is Associated with Soluble Forms of HLA. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11638. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311638

Krasnyi AM, Sorokina LE, Argentova-Stevens AM, Kokoeva DN, Alekseev AA, Jankevic T, Kan NE, Tyutyunnik VL, Sukhikh GT. Antibody-Dependent Cytotoxicity of Monocytes in Preeclampsia Is Associated with Soluble Forms of HLA. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11638. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311638

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrasnyi, Aleksey M., Leya E. Sorokina, Anastacia Maria Argentova-Stevens, Diana N. Kokoeva, Aleksey A. Alekseev, Tatjana Jankevic, Natalia E. Kan, Victor L. Tyutyunnik, and Gennady T. Sukhikh. 2025. "Antibody-Dependent Cytotoxicity of Monocytes in Preeclampsia Is Associated with Soluble Forms of HLA" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11638. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311638

APA StyleKrasnyi, A. M., Sorokina, L. E., Argentova-Stevens, A. M., Kokoeva, D. N., Alekseev, A. A., Jankevic, T., Kan, N. E., Tyutyunnik, V. L., & Sukhikh, G. T. (2025). Antibody-Dependent Cytotoxicity of Monocytes in Preeclampsia Is Associated with Soluble Forms of HLA. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11638. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311638