Natural Products as Potential Therapeutic Candidates for Diabetic Kidney Disease: Molecular Mechanisms, Translational Challenges, and Future Prospects

Abstract

1. Introduction

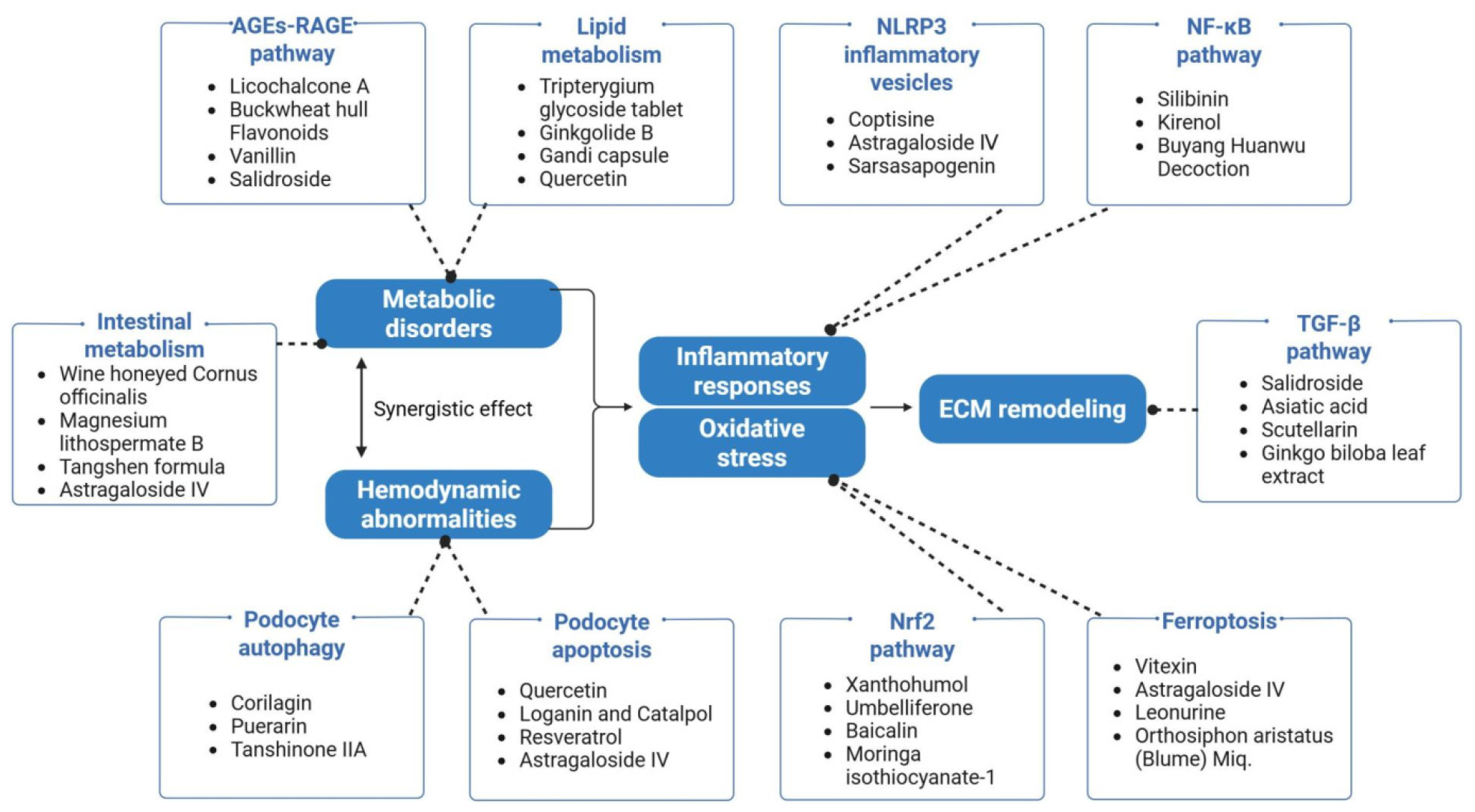

2. Pathogenesis in Diabetic Kidney Disease

2.1. Metabolic Disorder Regulatory Network

2.2. Hemodynamic Abnormalities

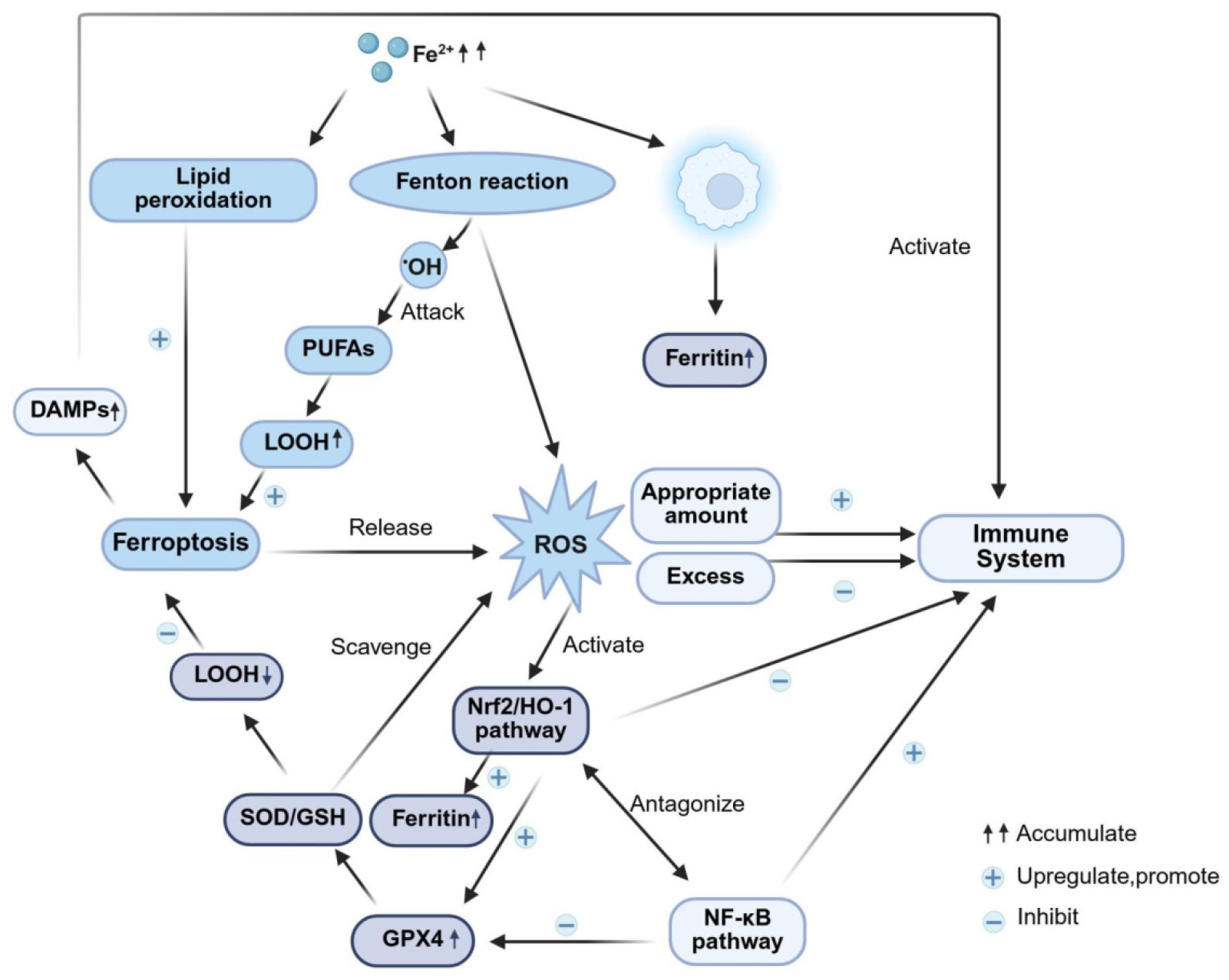

2.3. Inflammation–Oxidative Stress–Ferroptosis–Immunity: Pathological Amplification Core

2.4. ECM Remodeling: Terminal Damage of Fibrosis

2.5. Genetic Susceptibility

3. Therapeutic Drugs and Their Mechanistic Pathways

3.1. Metabolic Regulation: AGEs–RAGE–Lipids–Microbiota Cascade Synergistic Network

- AGEs-RAGE pathway modulation: Cellular and animal studies have validated the effectiveness of this intervention mechanism cascade. For instance, salidroside reduces AGE accumulation by inhibiting the RAGE/JAK1/STAT3 signaling axis [57]. However, current research exhibits notable limitations: the lack of human clinical trials to validate dose–response relationships leads to a fragmented evidence chain for clinical translation. Moreover, the correlation between pathway inhibition and attenuation of renal injury has only been confirmed in a single DKD model, and the therapeutic efficacy of intervention for DKD linked to distinct etiologies (type 1 vs. type 2 diabetes) is yet to be elucidated.

- Lipid Metabolism Regulation: The lipid metabolism regulatory effects of natural medicines are well-documented in animal studies. For instance, ginkgolide B stabilizes the expression of GPX4 while simultaneously improving lipid dysregulation and inhibiting ferroptosis [58]. Quercetin had also demonstrated reduced renal lipid deposition in small-sample clinical studies of early-stage DKD [59]. However, a core issue persists: large-scale trials have yet to verify differences in therapeutic efficacy across distinct DKD stages. Furthermore, the synergistic mechanisms of drugs targeting lipid breakdown (e.g., ATGL upregulation) versus those targeting lipid transport (e.g., SCAP/SREBP2 inhibition) have not been explored, leaving clinical combination therapy lacking a theoretical basis.

- Gut Microbiota Regulation: In animal studies, the correlation between modulation of the gut microbiota and renal protection has been validated. For instance, magnesium lithospermate B modulates gut microbiota composition and inhibits the conversion of p-cresol (PC) to p-cresol sulfonate (PCS), thereby mitigating renal injury [60], while wine-processed Cornus officinalis alleviates gut-derived renal injury by reshaping the gut microbial community [61]. However, existing research has limitations: quantitative evaluation indicators for regulating the “gut–kidney axis” (e.g., the threshold for decreased indole-3-sulfate levels) remain unestablished, and clinical microbiome detection data are insufficient to support these findings. Furthermore, the causal relationship between altered gut microbial structure and decreased renal toxic metabolites has not been validated through assays like fecal microbiota transplantation, rendering it challenging to rule out interfering factors from other metabolic pathways.

| Natural Products | Experiment Type | Disease Model | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buckwheat hull Flavonoids | in vivo | db/db mice | AGEs-RAGE pathway ↓ | [62] |

| Licochalcone A | in vivo | STZ-induced mice | AGEs-RAGE pathway ↓ | [63] |

| Tinospora cordifolia (Willd.) using polylactic acid nanoparticles | in vivo | STZ-induced rats | AGEs-RAGE pathway ↓ | [64] |

| Dieckol | in vitro | mGMCs | AGEs-RAGE pathway ↓ | [65] |

| Dang Gui Bu Xue decoction | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced mice HK-2 | AGEs-RAGE pathway ↓ | [17] |

| Geniposide | in vivo in vitro | db/db mice HEK293 | AGEs-RAGE pathway ↓ | [66] |

| Vanillin | in vivo | STZ-induced rats | AGEs-RAGE pathway ↓, NF-κB pathway ↓ | [67] |

| Syzygium cumini (L.) Skeels formulations | in vitro | HEK293 | AGEs-RAGE pathway ↓, NF-κB pathway ↓ | [68] |

| Loganin and Catalpol | in vivo in vitro | HFD-induced KK-Ay mice IMPC | AGEs-RAGE pathway ↓, p38 MAPK pathway ↓, NOX 4 pathway ↓ | [69] |

| Huang-Lian-Jie-Du Decoction | in vivo | db/db mice | AGEs/RAGE/Akt/Nrf2 pathway ↓ | [70] |

| Salidroside | in vivo | STZ-induced mice | RAGE/JAK1/STAT3 pathway ↓ | [57] |

| Catalpol | in vivo in vitro | HFD-induced KK-Ay mice mGECs, RAW264.7 macrophages | RAGE/RhoA/ROCK pathway ↓ | [71] |

| Natural Products | Experiment Type | Disease Model | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tripterygium glycoside tablet | in vivo | STZ-induced mice | ATGL ↑ | [72] |

| Ginkgolide B | in vivo in vitro | db/db mice MPC5 | Ubiquitination degradation of GPX4 ↓ | [58] |

| Gandi Capsule | in vivo in vitro | db/db mice MPC5 | SIRT1 ↑, AMPK ↑, HNF4A ↓ | [73] |

| Quercetin | in vivo | db/db mice | SCAP/SREBP2/LDLr pathway ↓ | [59] |

| Chrysin | in vivo | STZ-induced mice | AMPK ↑, SREBP1c ↓ | [74] |

| Yishen Huashi granule | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced rats HepG2 and CaCO2 cells | mTOR/AMPK/PI3K/AKT pathway ↓ | [75] |

3.2. Regulation of Podocyte Injury: The Balance Between Autophagy and Apoptosis

| Natural Products | Experiment Type | Disease Model | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corilagin | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced mice MPC5 | SIRT1-AMPK pathway ↑ | [79] |

| Puerarin | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced mice ciMPC | HMOX1/SIRT1 pathway ↑, AMPK pathway ↑; PERK/eIF2α/ATF4 pathway ↑ | [80,81] |

| Yishen capsule | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced rats MPC5 | SIRT1 ↑, NF-κB pathway ↓ | [82] |

| Selenized Tripterine Phytosomes | in vitro | MPC5 | SIRT1 ↑, NLRP3 ↓ | [83] |

| Astragalus polysaccharide | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced rats BFN60700330 | SIRT1/FoxO1 pathway ↑ | [84] |

| Emodin | in vivo | STZ-induced rats | AMPK ↑, mTOR ↓ | [85] |

| Kaempferol | in vivo | db/db mice | AMPK ↑, mTOR ↓ | [86] |

| Catalpol | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced mice ciMPC | mTOR/TFEB pathway ↑ | [78] |

| Vitamin D | in vivo | STZ-induced rats | mTOR ↓ | [87] |

| Yiqi Huoxue recipe | in vivo | STZ-induced rats | mTOR ↓, S6K1 ↓, LC3 ↑ | [88] |

| Geniposide | in vivo | STZ-induced mice | AMPK/ULK1 pathway ↑ | [89] |

| Tangshen Decoction | in vivo | STZ-induced rats | p-AMPK/p-ULK1 pathway ↑ | [90] |

| Huang-Gui solid dispersion | in vivo | STZ-induced rats db/db mice | AMPK pathway ↑ | [91] |

| Tanshinone IIA | in vivo in vitro | db/db mice MPC5 | PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway ↓ | [92] |

| Paecilomyces cicadae-fermented Radix astragali | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced mice Mouse podocyte cell lines | PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway ↓ | [93] |

| Celastrol | in vivo | STZ-induced rats | PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway ↓ | [94] |

| Curcumin | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced rats MPC5 | PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway ↓, Beclin1 ↑, UVRAG ↑ | [95,96] |

| Isoorientin | in vivo | STZ-induced mice MPC5 | PI3K/AKT/TSC2/mTOR pathway ↓ | [97] |

| Sarsasapogenin | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced rats mouse podocytes | GSK 3β pathway ↓ | [98] |

| Natural Products | Experiment Type | Disease Model | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quercetin | in vivo in vitro | db/db mice ciMPC | EGFR pathway ↓ | [99] |

| Zuogui Wan | in vivo in vitro | db/db mice ciMPC | p38/MAPK pathway ↓ | [100] |

| Huidouba | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced rats MPC5 | NOX 4—ROS pathway ↓ | [101] |

| Resveratrol | in vivo in vitro | db/db mice ciMPC | AMPK pathway ↑ | [102] |

| Astragaloside IV | in vivo in vitro | db/db mice ciMPC | PPARγ/Klotho/FoxO1 pathway ↑; Klotho ↑, NF-κB/NLRP3 axis ↓; IRE-1α/NF-κB/NLRP3 pathway ↓ | [11,12,13] |

| Baoshenfang formula | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced rats ciMPC | NOX 4/ROS/p38 pathway ↓ | [103] |

| Baicalin | in vitro | MPC5 | SIRT1/NF-κB pathway ↑ | [104] |

3.3. Inflammation Regulation: Core Interventions by NLRP3 and NF-κB

| Natural Products | Experiment Type | Disease Model | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coptisine | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced rats HK-2 cells | the NLRP3 inflammasome ↓ | [107] |

| Ferulic acid | in vivo | STZ-induced mice | the NLRP3 inflammasome ↓ | [110] |

| Hong Guo Ginseng Guo | in vivo | STZ-induced rats | the NLRP3 inflammasome ↓ | [111] |

| Crocin | in vivo | STZ-induced rats | the NLRP3 inflammasome ↓ | [112] |

| Berberine | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced rats HK-2 | the NLRP3 inflammasome ↓ | [113] |

| Sarsasapogenin | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced rats HMCs | PAR-1 ↓, the NLRP3 inflammasome ↓, NF-κB pathway ↓, AGEs-RAGE pathway ↓ | [114,115] |

| Dioscorea zingiberensis | in vivo | STZ-induced rats | the NLRP3 inflammasome ↓, p66Shc ↓ | [116] |

| Ethanolic extract from rhizome of Polygoni avicularis | in vivo in vitro | db/db mice HRMCs | TGF-β1/Smad pathway ↓, the NLRP3 inflammasome ↓ | [117] |

| Astragaloside IV | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced rats Immortalized rat podocytes | IRE-1α/NF-κB/NLRP3 pathway ↓ | [11] |

| Thonningianin A | in vivo | STZ-induced mice | NLRP3/ASC/Caspase-1 pathway ↓ | [118] |

| Cynapanosides A | in vivo in vitro | HFD-induced mice iMPC | NLRP3/NF-κB pathway ↓ | [119] |

| 6-Gingerol | in vivo | STZ-induced rats | miRNA-146a ↑, miRNA-223 ↑, TLR4/TRAF6/NLRP3 pathway ↓ | [120] |

3.4. “Iron Death Resistance–Antioxidation–Immunity” Cascade Regulation

- Antioxidant initiation pathway: The Nrf2 pathway acts as a key target for antioxidant defense regulation, and its diminished activity in DKD directly contributes to oxidative imbalance [126]. Natural medicines can scavenge ROS by upregulating Nrf2 and its downstream HO-1 expression; for instance, xanthohumol directly activates Nrf2 [127], whereas baicalin not only activates Nrf2 but also inhibits the MAPK signaling pathway [128]. However, a critical issue persists: the tissue specificity of Nrf2 activation unclarified, and the absence of renal-specific targeting drugs could induce side effects arising from systemic over-antioxidation.

- Core Mechanisms of Ferroptosis: Ferroptosis is a novel iron-dependent, lipid peroxidation-driven regulated cell death pathway. Renal tissue iron overload and decreased GPX4 activity in DKD are core mechanisms underlying ferroptosis [129]. Natural medicines can inhibit this pathway via multiple mechanisms: vitexin directly activates GPX4 [130], while Orthosiphon aristatus (Blume) Miq. indirectly regulates the expression of GPX4/ACSL4 by protecting mitochondrial function [131]. However, a contradiction persists: the molecular crosstalk mechanisms between ferroptosis inhibition and the Nrf2 pathway remain unclear. For instance, whether Nrf2 directly binds to the GPX4 promoter has not been validated using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays, precluding the distinction between direct and indirect regulatory effects.

- Immune-inflammation crosstalk: Both ferroptosis and oxidative stress activate inflammatory pathways such as the NLRP3 inflammasome and the NF-κB pathway, thereby releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-1β and TNF-α [132,133]. Natural medicines can counter-regulate immune-inflammatory responses through upstream cascade interventions. For example, leonurine (a compound from Leonurus japonicus) upregulates GPX4 expression via the Nrf2 pathway, thereby inhibiting ferroptosis and reducing the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines [134]. However, clinical translation confronts substantial challenges: the lack of dynamic monitoring data on iron metabolism (serum ferritin), oxidative stress (ROS levels), and immune markers (IL-1β concentration) in DKD patients hampers the establishment of clear biomarker thresholds to guide effective drug intervention.

| Natural Products | Experiment Type | Disease Model | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xanthohumol | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced mice GECs, HK-2 | Nrf2 pathway ↑ | [127] |

| Z-ligustilide | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced mice Hepa 1c1c7, HBZY- 1, RAW 264.7 | Nrf2 pathway ↑ | [135] |

| Syringic acid | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced rats NRK 52E | Nrf2 pathway ↑ | [136] |

| Rumex nervosus | in vivo | STZ-induced rats | Nrf2 pathway ↑ | [137] |

| Eriodictyol | in vivo | STZ-induced rats | Nrf2 pathway ↑ | [138] |

| Quercetin | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced rats HK-2 | Nrf2 pathway ↑ | [139] |

| Baicalin | in vivo | db/db mice | Nrf2 pathway ↑, MAPK pathway ↓ | [128] |

| Artemisinin | in vivo | STZ-induced rats | Nrf2 pathway ↑, TGF-β1 ↓ | [140] |

| Chlorogenic acid | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced rats HK-2 | Nrf2 pathway ↑, the NLRP3 inflammasome ↓ | [141] |

| Isoeucommin A | in vitro | HRMCs, RTECs | Nrf2/HO-1 pathway ↑ | [142] |

| Umbelliferone | in vivo in vitro | db/db mice HK-2 | Nrf2/HO-1 pathway ↑ | [143] |

| Tetrandrine | in vivo | STZ-induced rats | Nrf2/HO-1 pathway ↑ | [144] |

| Sinapic acid | in vivo | STZ-induced rats | Nrf2/HO-1 pathway ↑ | [145] |

| Moringa oleifera Lam. Seed extract | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced rats HRMCs | Nrf2/HO-1 pathway ↑ | [146] |

| Asiaticoside | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced rats HBZY-1 | Nrf2/HO-1 pathway ↑ | [147] |

| Kaempferol | in vivo | STZ-induced rats | Nrf2/HO-1 pathway ↑ | [148] |

| Neferine | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced mice HMCs | miR-17-5p ↓, Nrf2/HO-1 pathway ↑ | [149] |

| Eucommia lignans | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced rats HBZY-1 | AR ↓, Nrf2/HO-1 pathway ↑, AMPK pathway ↑ | [150] |

| Triptolide | in vivo in vitro | db/db mice, STZ-induced mice; SV40-MES-13, MPC5 | Phosphorylation of GSK3β ↓, Nrf2 ↑, HO-1 ↑; the NLRP3 inflammasome↓ | [151,152] |

| Moringa isothiocyanate -1 | in vivo | db/db mice | ERK/Nrf2/HO-1 pathway ↑, NF-κB pathway↓ | [153] |

| Epigallocatechin-3-gallate | in vivo | STZ-induced rats | Nrf2/ARE pathway ↑ | [154] |

| Obacunone | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced rats HK-2 | Nrf2-KEAP1 pathway ↓ | [155] |

| Natural Products | Experiment Type | Disease Model | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitexin | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced rats HK-2 | GPX4 ↑ | [130] |

| Astragaloside IV | in vivo | db/db mice | GPX4 ↑, xCT ↑, GSH/GSSG ↑, ACSL4 ↓ | [14] |

| Orthosiphon aristatus (Blume) Miq | in vivo | db/db mice | NCOA4 ↓, ACSL4 ↓, FTH1 ↑, GPX4 ↑ | [131] |

| Jian-Pi-Gu-Shen-Hua-Yu decoction | in vivo | STZ-induced mice | GPX4 pathway ↑ | [156] |

| leonurine | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced mice HUVECs | Nrf2/GPX4 pathway ↑ | [134] |

| Rhein | in vivo in vitro | db/db mice MPC5 | Rac1/NOX1/β—catenin axis ↓, SLC7A11/GPX4 axis ↑ | [157] |

| San-Huang-Yi-Shen capsule | in vivo | STZ-induced mice | Cystine/GSH/GPX4 axis ↑ | [158] |

| Ginkgolide B | in vivo in vitro | db/db mice MPC5 | Ubiquitination degradation of GPX4 ↓ | [58] |

| Germacrone | in vivo | db/db mice | mtDNA/cGAS/STING pathway ↓ | [159] |

| Tanshinone IIA | in vivo in vitro | db/db mice MPC5 | ELAVL1-ACSL4 axis ↓ | [160] |

| Schisandrin A | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced mice HRGECs | AdipoR1/AMPK pathway ↑ | [161] |

3.5. Anti-Fibrosis: A Key Intervention in Mid-to-Late-Stage DKD

| Natural Products | Experiment Type | Disease Model | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ginkgo biloba leaf extract | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced rats HBZY-1 | TGF-β ↓ | [165] |

| Luteolin | in vivo | STZ-induced mice | AMPK pathway ↑, NF-κB pathway ↓, TGF-β1 ↓ | [166] |

| Scutellarin | in vivo | STZ-induced mice | TGF-β1 pathway ↓, MAPKs pathway ↓, Wnt/β-catenin pathway ↓ | [167] |

| Krill oil | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced mice MCs | TGF-β pathway ↓ | [168] |

| Danggui Buxue decoction | in vivo | HFD-induced rats | TGF-β1/Smad pathway ↓ | [16] |

| Dendrobium mixture | in vivo | db/db mice | TGF-β1/Smad pathway ↓ | [169] |

| Fuxin Granules | in vivo | db/db mice | TGF-β1/Smad pathway ↓, VEGF/VEGFR2 pathway ↓ | [163] |

| Astragaloside IV | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced rats RMC | TGF-β1/Smad/miR-192 pathway ↓ | [15] |

| The combination of ursolic acid and empagliflozin | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced rats HBZY-1 | TGF-β/Smad/MAPK pathway ↓ | [170] |

| Qishen Yiqi Dripping Pill | in vivo | STZ-induced rats | Wnt/β-catenin pathway ↓, TGF-β/Smad2 pathway ↓ | [171] |

| Asiatic acid | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced rats HK-2 | TGF-β1/Smad3 pathway ↓ | [164] |

| Crocin | in vivo | STZ-induced mice | CYP4A11/PPARγ pathway ↑, TGF-β1/Smad3 pathway ↓ | [172] |

| Magnoflorine | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced rats SV40-MES13 | Ubiquitination of KDM3A ↑, TGIF1 ↑, TGF-β1/Smad2/3 pathway ↓ | [173] |

| Taurine | in vivo | STZ-induced rats | TGF-β/Smad2/3 pathway ↓, p38 MAPK pathway↓ | [174] |

| Cyanidin-3-glucoside | in vivo | STZ-induced rats | TGF-β1/Smad2/3 pathway ↓ | [175] |

| Chrysophanol | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced mice AB8/13 | TGF-β/EMT pathway ↓ | [176] |

| Huangkui capsule in combination with metformin | in vivo in vitro | STZ-induced rats HK-2 | Klotho/TGF-β1/p38 pathway ↓ | [177] |

4. Limitations of Existing Research

- Low-quality evidence: Over 90% of studies are conducted in cell and animal models, accompanied by limited clinical data and small sample sizes.

- Inadequate model applicability: The commonly used streptozotocin (STZ)-induced DKD model predominantly displays acute kidney injury characteristics, which is severely inconsistent with the chronic pathological process of human DKD—marked by “long-term hyperglycemic injury followed by gradual glomerulosclerosis—and fails to replicate the complex clinical complications commonly seen in patients, such as metabolic disorders and vascular lesions. Consequently, experimental outcomes have limited clinical relevance, failing to recapitulate the “progressive renal function decline” observed in human DKD. Furthermore, it fails to replicate complex clinical complications commonly observed in clinical settings, such as metabolic disorders and vascular lesions, thereby limiting the clinical relevance of experimental findings [178].

- Research design deficiencies: In animal studies, researchers often use drug doses far exceeding human tolerable levels to achieve obvious efficacy. However, the dose–response relationships and toxic reactions observed at these high doses do not directly correspond to the safe dosage range for human clinical use. This directly leads to the translational dilemma where treatments are effective in animals but ineffective in humans. Additionally, critical experimental parameters—such as optimal dosage, administration methods, and long-term safety profiles of natural medicines—are frequently lacking. Multi-targeted cross-regulatory networks and cascading molecular interaction mechanisms remain incompletely elucidated, while contradictions such as disease progression adaptation and clinical positioning strategies remain unresolved.

- The “file-drawer problem”: This phenomenon is common in preclinical research—positive results are more likely to be published, while numerous negative or weakly positive findings are left unpublished due to “insufficient academic value.” This introduces a selective bias into the existing evidence chain in the literature, failing to accurately reflect a drug’s actual development potential.

5. Advantages of Natural Medicines

6. Development Bottlenecks of Natural Medicines

6.1. Difficulties in Drug Quality Control

6.2. Uncertainty About Drug Safety

6.3. Relatively Slow Treatment Effect

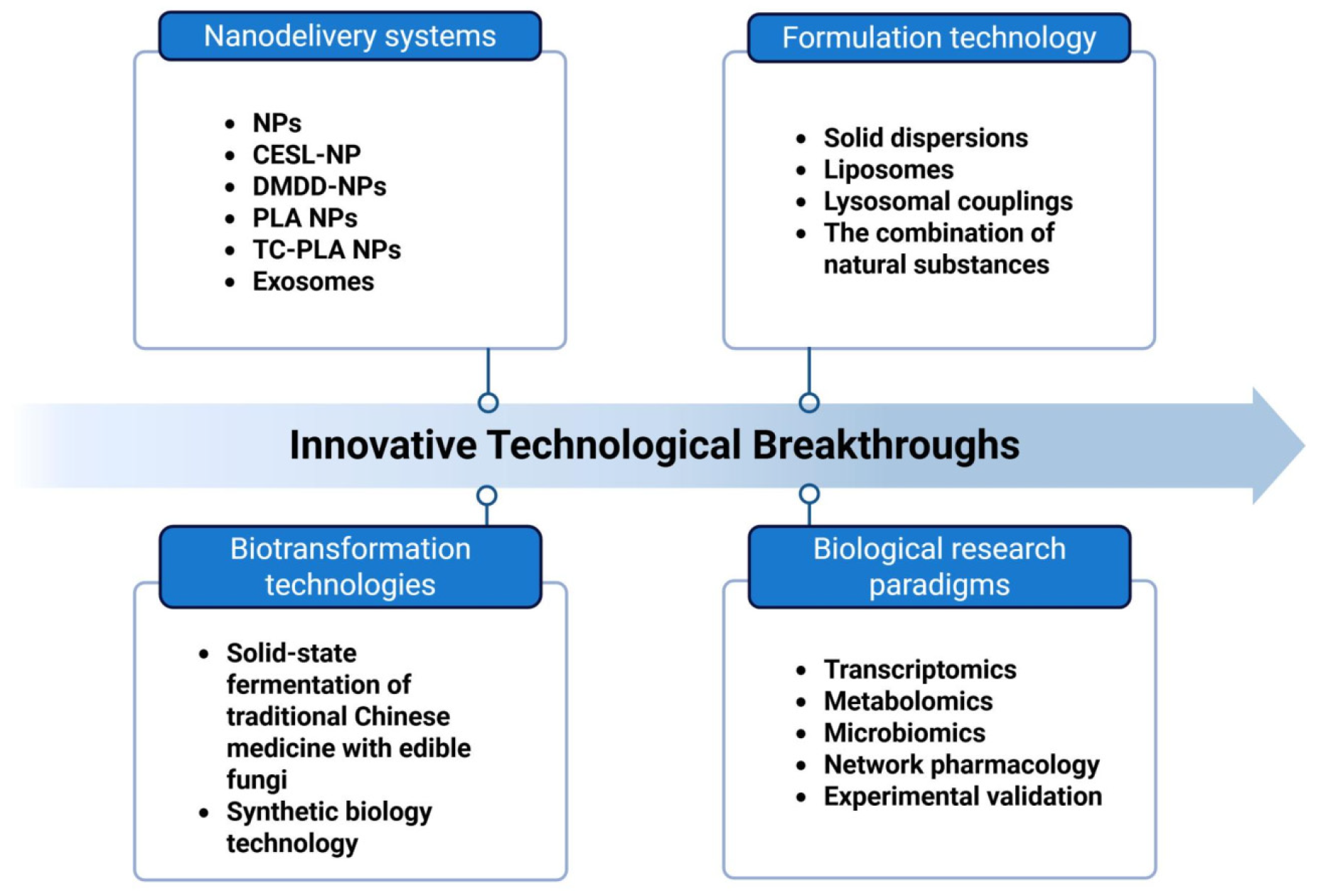

7. Technological Innovations and Solutions

7.1. Development of a Transformation Roadmap: Multi-Technology Synergy in Overcoming Natural Compound Application Barriers

7.1.1. Nanodelivery Systems

7.1.2. Formulation Redesign

7.1.3. Bioconversion and Synthetic Biology

7.2. Multi-Technology Integration Supports Precision Development of Natural Medicines for DKD

7.2.1. Synergistic Application of Multi-Omics and Network Pharmacology

7.2.2. AI Target Prediction: A Critical Complement to Precision Screening

8. Clinical Practice of Natural Medicines

| Natural Products | Conditions | Dose | Test Duration | Primary Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abelmoschus manihot | 2054 patients with CKD and proteinuria (≥150 mg/d) | 12 years: 2.5 g TID; 6 to 12 years: 1.5 g TID; 2 to 6 years: 1 g TID | 24 weeks | Proteinuria ↓ | [210] |

| Abelmoschus manihot | 413 patients with T2DM and DKD | 2.5 g TID | 24 weeks | Urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio ↓ | [211] |

| Triptery gium wilfordii hook f extract | 65 patients with T2DM and DKD who had proteinuria levels ≥ 2.5 g/24 h and serum creatinine levels < 3 mg/dL | 120 mg daily for 3 months, followed by 60 mg daily for 3 months. | 6 months | Proteinuria ↓ | [212] |

| Resveratrol | 60 patients with T2DM and DKD | 500mg daily | 90 days | Albuminuria ↓ | [213] |

| Zicuiyin | 88 patients with T2DM and DKD | crude drug amount 75 g, 150 mL, BID | 8 weeks | eGFR ↑ | [214] |

| Qidan Tangshen Granule | 219 patients with T2DM and DKD | - | 3 months and 12 months | Hemoglobin A1c and albumin-to-creatinine ratio ↓ | [215] |

| Turmeric | 40 patients with T2DM and DKD | 22.1 mg, TID | 2 months | Proteinuria ↓, TGF-β ↓, IL-8 ↓ | [216] |

- Abelmoschus manihot

- Tripterygium wilfordii Hook. f. Extract

- Zicuiyin Decoction

- Resveratrol

- Qidan Tangshen Granule and Curcumin

- Other natural products

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DKD | diabetic kidney disease |

| TGF-β | transforming growth factor-β |

| T2DM | type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| CKD | chronic kidney disease |

| SGLT2 | sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 |

| ESKD | end-stage kidney disease |

| GLP-1 | glucagon-like peptide 1 |

| MRAs | mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists |

| SGLT2i | SGLT-2 inhibitors |

| Smad | small mothers against decapentaplegic |

| AGEs | advanced glycation end products |

| GIP | glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide |

| GLP-1 | glucagon-like peptide-1 |

| GFR | glomerular filtration rate |

| RAAS | renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system |

| ECM | extracellular matrix |

| IL | interleukin |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-α |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| RAGE | receptor for advanced glycation end products |

| NF-κB | nuclear transcription factor κB |

| p38 | p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinases |

| NLRP3 | NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 |

| Nrf2 | nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| JAK1 | janus kinase 1 |

| STAT3 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| GPX4 | glutathione peroxidase 4 |

| TG | triglycerides |

| ATGL | adipose triglyceride lipase |

| SIRT1 | silent information regulator sirtuin 1 |

| AMPK | amp-activated protein kinase |

| HNF4A | hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha |

| SCAP | sterol regulatory element-binding protein cleavage-activating protein |

| SREBP2 | sterol regulatory element-binding protein 2 |

| LDLr | low density lipoprotein receptor |

| PC | p-cresol |

| PCS | p-cresol sulfate |

| TLR4 | toll-like receptor 4 |

| mTOR | mechanistic target of rapamycin |

| TFEB | transcription factor EB |

| S6K1 | ribosomal protein S6 kinase beta-1 |

| LC3 | microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 |

| PI3K | phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| AKT | protein kinase B |

| PERK | protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase |

| eIF2α | eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 alpha |

| ATF4 | activating transcription factor 4 |

| EGFR | epidermal growth factor receptor |

| PPARγ | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma |

| FoxO1 | forkhead box O1 |

| IRE-1α | inositol requiring enzyme 1 alpha |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell Lymphoma 2 protein |

| Bax | Bcl-2 Associated X protein |

| NOX 4 | nadph oxidase 4 |

| ASC | apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD |

| PAR-1 | protease-activated receptor 1 |

| α-SMA | alpha-smooth muscle actin |

| HO-1 | heme oxygenase-1 |

| ARE | antioxidant response element |

| miR | miRNA |

| AR | androgen receptor |

| ERK | extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| ACSL4 | acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 |

| xCT | solute carrier family 7 member 11 |

| FTH1 | ferritin heavy chain 1 |

| NCOA4 | nuclear receptor coactivator 4 downregulated |

| ELAVL1 | elav like rna binding protein 1 |

| AdipoR1 | adiponectin receptor 1 |

| mtDNA | mitochondrial DNA |

| cGAS | cyclic GMP-AMP synthase |

| STING | stimulator of interferon genes |

| VEGF | vascular endothelial growth factor |

| KDM3A | lysine demethylase 3A |

| CYP4A11 | cytochrome P450 family 4 subfamily A member 11 |

| EMT | epithelial–mesenchymal transition |

| TP53 | tumor protein p53 |

| CASP8 | caspase 8 |

| CASP3 | caspase 3 |

| MYC | v-myc avian myelocytomatosis viral oncogene homolog |

| JUN | v-jun avian sarcoma virus 17 oncogene homolog |

| PTGS2 | prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 |

| ACEI | angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor |

| PLA-PEG | poly lactic acid-polyethylene glycol |

| ARB | angiotensin II receptor blocker |

References

- IDF. Diabetes Atlas. Available online: https://diabetesatlas.org/ (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Forouhi, N.G.; Wareham, N.J. Epidemiology of Diabetes. Medicine 2014, 42, 698–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.C.; Cooper, M.E.; Zimmet, P. Changing Epidemiology of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Associated Chronic Kidney Disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2016, 12, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, P.E.; Ahmed, S.B.; Carrero, J.J.; Foster, B.; Francis, A.; Hall, R.K.; Herrington, W.G.; Hill, G.; Inker, L.A.; Kazancıoğlu, R.; et al. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). CKD Work Group KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2024, 105, S117–S314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luk, A.; Chan, J.C.N. Diabetic Nephropathy—What Are the Unmet Needs? Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2008, 82 (Suppl. S1), S15–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerspink, H.J.L.; Parving, H.-H.; Andress, D.L.; Bakris, G.; Correa-Rotter, R.; Hou, F.-F.; Kitzman, D.W.; Kohan, D.; Makino, H.; McMurray, J.J.V.; et al. Atrasentan and Renal Events in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Chronic Kidney Disease (SONAR): A Double-Blind, Randomised, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Lancet 2019, 393, 1937–1947, Erratum in Lancet 2019, 393, 1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.K.; Bhatt, D.L.; Cosentino, F.; Marx, N.; Rotstein, O.; Pitt, B.; Pandey, A.; Butler, J.; Verma, S. Non-Steroidal Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists in Cardiorenal Disease. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 2931–2945, Erratum in Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 4391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kintscher, U.; Bakris, G.L.; Kolkhof, P. Novel Non-Steroidal Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists in Cardiorenal Disease. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 179, 3220–3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaze, A.D.; Zhuo, M.; Kim, S.C.; Patorno, E.; Paik, J.M. Association of SGLT2 Inhibitors with Cardiovascular, Kidney, and Safety Outcomes among Patients with Diabetic Kidney Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2022, 21, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, M.; Pecoits-Filho, R. Can We Cure Diabetic Kidney Disease? Present and Future Perspectives from a Nephrologist’s Point of View. J. Intern. Med. 2022, 291, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.L.; Guo, Z.Y.; Liu, W.Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Hu, Y.L.; Li, S.F.; Zhang, M.Y.; Zhang, G.; Wang, J.J.; et al. Astragaloside IV Alleviates Podocyte Injury in Diabetic Nephropathy through Regulating IRE-1α/NF-κ B/NLRP3 Pathway. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2025, 31, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, L.; Fang, J.; Zhu, B.; Wang, L.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Huang, J.; Wang, H.; Yao, X. Astragaloside IV Protects against Podocyte Apoptosis by Inhibiting Oxidative Stress via Activating PPARγ-Klotho-FoxO1 Axis in Diabetic Nephropathy. Life Sci. 2021, 269, 119068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Cui, J.; Shi, Y.; Wang, T.; Xin, J.; Li, Y.; Shan, X.; Zhu, Z.; Gao, Y. Astragaloside IV Attenuates High-Glucose-Induced Impairment in Diabetic Nephropathy by Increasing Klotho Expression via the NF-κ B/NLRP3 Axis. J. Diabetes Res. 2023, 2023, 7423661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.; Zhang, T.-T.; Ye, Z.; Chen, C. Astragaloside IV Mitigated Diabetic Nephropathy by Restructuring Intestinal Microflora and Ferroptosis. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2024, 68, e2300734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Q.; Chen, C.; Liang, H.; Zhong, S.; Cheng, X.; Li, L. Astragaloside IV Inhibits Excessive Mesangial Cell Proliferation and Renal Fibrosis Caused by Diabetic Nephropathy via Modulation of the TGF-Β1/Smad/miR-192 Signaling Pathway. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019, 18, 3053–3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Gu, L.; Li, Z.; Zhu, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, L.; Xue, M. Efficacy of Danggui Buxue Decoction on Diabetic Nephropathy-Induced Renal Fibrosis in Rats and Possible Mechanism. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2023, 43, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.T.; Qi, Y.; Chen, P.; Chen, L.; Jiang, Y.; Fan, Z.; Guan, H.; Bai, L.; Liu, J.; Zhao, D.; et al. Dang-Gui-Bu-Xue Decoction against Diabetic Nephropathy via Modulating the Carbonyl Compounds Metabolic Profile and AGEs/RAGE Pathway. Phytomed. Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2024, 135, 156104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.P. Aldose Reductase, Glomerular Metabolism, and Diabetic Nephropathy. Metabolism 1986, 35, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgkinson, A.D.; Søndergaard, K.L.; Yang, B.; Cross, D.F.; Millward, B.A.; Demaine, A.G. Aldose Reductase Expression Is Induced by Hyperglycemia in Diabetic Nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2001, 60, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vistoli, G.; De Maddis, D.; Cipak, A.; Zarkovic, N.; Carini, M.; Aldini, G. Advanced Glycoxidation and Lipoxidation End Products (AGEs and ALEs): An Overview of Their Mechanisms of Formation. Free. Radic. Res. 2013, 47, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrofanova, A.; Fontanella, A.M.; Merscher, S.; Fornoni, A. Lipid Deposition and Metaflammation in Diabetic Kidney Disease. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2020, 55, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Tan, E.; Shi, H.; Ren, X.; Wan, X.; Wu, W.; Chen, Y.; Niu, H.; Zhu, G.; Li, J.; et al. Mitochondrial Oxidative Damage Reprograms Lipid Metabolism of Renal Tubular Epithelial Cells in the Diabetic Kidney. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2024, 81, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrofanova, A.; Burke, G.; Merscher, S.; Fornoni, A. New Insights into Renal Lipid Dysmetabolism in Diabetic Kidney Disease. World J. Diabetes 2021, 12, 524–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman-Edelstein, M.; Scherzer, P.; Tobar, A.; Levi, M.; Gafter, U. Altered Renal Lipid Metabolism and Renal Lipid Accumulation in Human Diabetic Nephropathy. J. Lipid Res. 2014, 55, 561–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Q.M.; Jin, H.M.; Yang, X.H. Lipid Abnormality in Diabetic Kidney Disease and Potential Treatment Advancements. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1503711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, J.S. Role of the Incretin Pathway in the Pathogenesis of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 2009, 76 (Suppl. S5), S12–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, L.; Chu, J.; Li, H.; Sun, W.; Yang, C.; Wang, H.; Dai, W.; et al. Alterations of the Gut Microbiota in Patients with Diabetic Nephropathy. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e00324-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iatcu, C.O.; Steen, A.; Covasa, M. Gut Microbiota and Complications of Type-2 Diabetes. Nutrients 2021, 14, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.-X.; Chen, X.; Zang, S.-G.; Chen, X.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Wu, L.-P.; Xuan, S.-H. Gut Microbiota Microbial Metabolites in Diabetic Nephropathy Patients: Far to Go. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1359432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, M.; Zhao, X.; Xia, F.; Shi, M.; Zhao, D.; Li, L.; Jiang, H. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Metabolic Reprogramming in Acute Kidney Injury: Mechanisms, Therapeutic Advances, and Clinical Challenges. Front. Physiol. 2025, 16, 1623500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, R.G.; Guedes, G.D.S.; Vasconcelos, S.M.L.; Santos, J.C.D.F. Kidney Disease in Diabetes Mellitus: Cross-Linking between Hyperglycemia, Redox Imbalance and Inflammation. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2019, 112, 577–587, Erratum in Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2019, 113, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helal, I.; Fick-Brosnahan, G.M.; Reed-Gitomer, B.; Schrier, R.W. Glomerular Hyperfiltration: Definitions, Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2012, 8, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassén, E.; Daehn, I.S. Molecular Mechanisms in Early Diabetic Kidney Disease: Glomerular Endothelial Cell Dysfunction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacchetti, G.; Sechi, L.A.; Rilli, S.; Carey, R.M. The Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System, Glucose Metabolism and Diabetes. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 16, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luther, J.M.; Brown, N.J. Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System and Glucose Homeostasis. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2011, 32, 734–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, H.; Xing, Y.-F.; Ye, Z.-C.; Li, C.-M.; Luo, P.-L.; Li, M.; Lou, T.-Q. High Glucose Induces Activation of the Local Renin-Angiotensin System in Glomerular Endothelial Cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2014, 9, 450–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Garre, D.; Ruiz-Ortega, M.; Ortego, M.; Largo, R.; López-Armada, M.J.; Plaza, J.J.; González, E.; Egido, J. Effects and Interactions of Endothelin-1 and Angiotensin II on Matrix Protein Expression and Synthesis and Mesangial Cell Growth. Hypertension 1996, 27, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.X.; Hu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Ma, Z.Y.; Feng, J.B.; Wang, R.; Wang, X.P.; Dong, B.; Gao, F.; et al. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) 2 Overexpression Ameliorates Glomerular Injury in a Rat Model of Diabetic Nephropathy: A Comparison with ACE Inhibition. Mol. Med. 2011, 17, 59–69, Erratum in Mol. Med. 2022, 28, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyawali, P.; Richards, R.S. Association of Altered Hemorheology with Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Metabolic Syndrome. Redox Rep. Commun. Free Radic. Res. 2015, 20, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donath, M.Y.; Shoelson, S.E. Type 2 Diabetes as an Inflammatory Disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donate-Correa, J.; Ferri, C.M.; Sánchez-Quintana, F.; Pérez-Castro, A.; González-Luis, A.; Martín-Núñez, E.; Mora-Fernández, C.; Navarro-González, J.F. Inflammatory Cytokines in Diabetic Kidney Disease: Pathophysiologic and Therapeutic Implications. Front. Med. 2021, 7, 628289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayego-Mateos, S.; Morgado-Pascual, J.L.; Opazo-Ríos, L.; Guerrero-Hue, M.; García-Caballero, C.; Vázquez-Carballo, C.; Mas, S.; Sanz, A.B.; Herencia, C.; Mezzano, S.; et al. Pathogenic Pathways and Therapeutic Approaches Targeting Inflammation in Diabetic Nephropathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-C.; Chang, Y.-H.; Yang, S.-Y.; Wu, K.-D.; Chu, T.-S. Update of Pathophysiology and Management of Diabetic Kidney Disease. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2018, 117, 662–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, L.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, P.; Shu, H.; Yang, C.; Chu, Y.; Liu, J. Ferroptosis: An Important Player in the Inflammatory Response in Diabetic Nephropathy. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1294317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Kroemer, G.; Kang, R. Ferroptosis in Immunostimulation and Immunosuppression. Immunol. Rev. 2024, 321, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antar, S.A.; Ashour, N.A.; Marawan, M.E.; Al-Karmalawy, A.A. Fibrosis: Types, Effects, Markers, Mechanisms for Disease Progression, and Its Relation with Oxidative Stress, Immunity, and Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hills, C.E.; Squires, P.E. The Role of TGF-β and Epithelial-to Mesenchymal Transition in Diabetic Nephropathy. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 2011, 22, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Jia, H.; Hou, Q.; Jin, L.; Ahsan, M.A.; Li, G.; Guan, T.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Z.; Xie, J.; et al. Multimodal Analysis Stratifies Genetic Susceptibility and Reveals the Pathogenic Mechanism of Kidney Injury in Diabetic Nephropathy. Cell Rep. Med. 2025, 6, 102249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seaquist, E.R.; Goetz, F.C.; Rich, S.; Barbosa, J. Familial Clustering of Diabetic Kidney Disease. Evidence for Genetic Susceptibility to Diabetic Nephropathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1989, 320, 1161–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, S.; Raza, S.T.; Mahdi, F. Association of Genetic Variants with Diabetic Nephropathy. World J. Diabetes 2014, 5, 809–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florez, J.C. Genetics of Diabetic Kidney Disease. Semin. Nephrol. 2016, 36, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, J.; Navarro, C.; Ortega, Á.; Nava, M.; Morillo, D.; Torres, W.; Hernández, M.; Cabrera, M.; Angarita, L.; Ortiz, R.; et al. Advanced Glycation End Products: New Clinical and Molecular Perspectives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wei, N.; Yu, C.; Li, C.; Li, W.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Xie, J. Natural Polysaccharides: The Potential Biomacromolecules for Treating Diabetes and Its Complications via AGEs-RAGE-Oxidative Stress Axis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 143, 113426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Fu, L.; Zhang, C.; Wang, S.; Song, J.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, F. Targeting Ferroptosis With Natural Products to Treat Diabetes and Its Complications: Opportunities and Challenges. Phytother. Res. 2025, 0, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.M.; Clardy, J.; Xavier, R.J. Gut Microbiome Lipid Metabolism and Its Impact on Host Physiology. Cell Host Microbe 2023, 31, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.; Zheng, L.; Nan, S.; Ke, L.; Fu, Z.; Jin, J. Enterorenal Crosstalks in Diabetic Nephropathy and Novel Therapeutics Targeting the Gut Microbiota. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2022, 54, 1406–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leng, C.-L.; Lin, K.; Zhou, M.; Ye, X.-S.; Shu, X.-J.; Liu, W. Protective Effect of Salidroside on Renal Damage in Diabetic Nephropathy Mice by Regulating RAGE/JAK1/STAT Signaling Pathway. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2024, 49, 2188–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ou, Z.; Gao, T.; Yang, Y.; Shu, A.; Xu, H.; Chen, Y.; Lv, Z. Ginkgolide B Alleviates Oxidative Stress and Ferroptosis by Inhibiting GPX4 Ubiquitination to Improve Diabetic Nephropathy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 156, 113953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Yu, J.; Wang, X.; Ge, J.; Li, N. Quercetin Improves Lipid Metabolism via SCAP-SREBP2-LDLr Signaling Pathway in Early Stage Diabetic Nephropathy. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2019, 12, 827–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, N.; Duan, H.; Feng, Y.; Xu, W.; Shen, J.; Wang, K.; Liu, J. Magnesium Lithospermate B Ameliorates Diabetic Nephropathy by Suppressing the Uremic Toxin Formation Mediated by Gut Microbiota. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 953, 175812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, C.G.; Zhu, L.; Wang, W.; Gao, H.; Xu, Y.B.; Jia, T.Z. Cornus officinalis Prior and Post-Processing: Regulatory Effects on Intestinal Flora of Diabetic Nephropathy Rats. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1039711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Dai, W.; Zhang, L.; Piao, C. Flavonoids Derived from Buckwheat Hull Can Break Advanced Glycation End-Products and Improve Diabetic Nephropathy. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 7161–7170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Li, T.; Gao, Q.; Chen, Y.; Su, G.; Zhao, Y. Impact of Licochalcone a on the Progression of Diabetic Nephropathy in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus of C57BL/6 Mice. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 10676–10689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambalavanan, R.; John, A.D.; Selvaraj, A.D. Nephroprotective Role of Nanoencapsulated Tinospora cordifolia (Willd.) Using Polylactic Acid Nanoparticles in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Nephropathy Rats. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 15, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.-H.; Yoo, G.; Kim, M.; Kurniawati, U.D.; Choi, I.-W.; Lee, S.-H. Dieckol, Derived from the Edible Brown Algae Ecklonia cava, Attenuates Methylglyoxal-Associated Diabetic Nephropathy by Suppressing AGE-RAGE Interaction. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Ni, Y.; Chen, C.; Dong, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, W. Geniposide Ameliorates Diabetic Nephropathy in Type 2 Diabetic Mice by Targeting AGEs-RAGE-Dependent Inflammatory Pathway. Phytomed. Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2024, 135, 156046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iem, Z.; Mn, A.; Mm, E.-S. Protective Effect of Vanillin on Diabetic Nephropathy by Decreasing Advanced Glycation End Products in Rats. Life Sci. 2019, 239, 117088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apte, M.M.; Khattar, E.; Tupe, R.S. Mechanistic Role of Syzygium cumini (L.) Skeels in Glycation Induced Diabetic Nephropathy via RAGE-NF-κB Pathway and Extracellular Proteins Modifications: A Molecular Approach. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 322, 117573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, J.; Jiang, M.; Fu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Jiao, N.; Liu, L.; Du, Q.; Wu, H.; Xu, H.; et al. Loganin and Catalpol Exert Cooperative Ameliorating Effects on Podocyte Apoptosis upon Diabetic Nephropathy by Targeting AGEs-RAGE Signaling. Life Sci. 2020, 252, 117653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; He, W.-J.; Zhang, Z.-T.; Shi, J.-J.; Wang, X.; Gu, W.-T.; Chen, Z.-Q.; Xu, Y.-H.; Chen, Y.-B.; Wang, S.-M. Protective Effects of Huang-Lian-Jie-Du Decoction on Diabetic Nephropathy through Regulating AGEs/RAGE/Akt/Nrf2 Pathway and Metabolic Profiling in Db/Db Mice. Phytomedicine 2022, 95, 153777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, A.; Du, Q.; Chen, J.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Lv, G.; Lu, J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, H. Catalpol Ameliorates Endothelial Dysfunction and Inflammation in Diabetic Nephropathy via Suppression of RAGE/RhoA/ROCK Signaling Pathway. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2021, 348, 109625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, S.-L.; Lin, W.; Pan, R.-H.; Dai, Y.; Xia, Y.-F. Tripterygium Glycoside Tablet Attenuates Renal Function Impairment in Diabetic Nephropathy Mice by Regulating Triglyceride Metabolism. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2022, 221, 115028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Yao, H.; Li, C.; Sun, W.; Chen, X.; Cao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Qi, J.; et al. Gandi Capsule Improved Podocyte Lipid Metabolism of Diabetic Nephropathy Mice through SIRT1/AMPK/HNF4A Pathway. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 6275505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Tao, H.; Xu, N.; Zhou, S.; Peng, Y.; Zhu, J.; Liu, S.; Chang, Y. Chrysin Improves Diabetic Nephropathy by Regulating the AMPK-Mediated Lipid Metabolism in HFD/STZ-Induced DN Mice. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Xiang, Q.; Lie, B.; Chen, D.; Li, M.; Zhang, X.; Yang, J.; He, B.; Zhang, W.; Dong, R.; et al. Yishen Huashi Granule Modulated Lipid Metabolism in Diabetic Nephropathy via PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathways. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda-Yamahara, M.; Kume, S.; Tagawa, A.; Maegawa, H.; Uzu, T. Emerging Role of Podocyte Autophagy in the Progression of Diabetic Nephropathy. Autophagy 2015, 11, 2385–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Banu, K.; Ni, Z.; Leventhal, J.S.; Menon, M.C. Podocyte Autophagy in Homeostasis and Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, Q.; Shan, Z.; Mi, W.; Zhao, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, B.; Zheng, X.; Feng, W. Catalpol Ameliorates Podocyte Injury by Stabilizing Cytoskeleton and Enhancing Autophagy in Diabetic Nephropathy. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; Luan, Y.-T.; Rong, W.-Q.; Gai, Y. Corilagin Alleviates Podocyte Injury in Diabetic Nephropathy by Regulating Autophagy via the SIRT1-AMPK Pathway. World J. Diabetes 2024, 15, 1916–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhu, Q.; Zheng, R.; Yan, J.; Wei, M.; Fan, Y.; Deng, Y.; Zhong, Y. Puerarin Attenuates Diabetic Nephropathy by Promoting Autophagy in Podocytes. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Chen, B.; Huang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Liang, T. The Effects of Puerarin on Autophagy through Regulating of the PERK/eIF2α/ATF4 Signaling Pathway Influences Renal Function in Diabetic Nephropathy. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2020, 13, 2583–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y.; Lei, Q.; Sun, D.; Liu, T.; Fan, Y.; et al. Yishen Capsule Promotes Podocyte Autophagy through Regulating SIRT1/NF-κB Signaling Pathway to Improve Diabetic Nephropathy. Ren. Fail. 2021, 43, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Liu, Q.; Chang, Y.; Luo, C.; Zhang, X.; Sun, S. Integrated Network Pharmacology and Cellular Assay to Explore the Mechanisms of Selenized Tripterine Phytosomes (Se@tri-PTs) Alleviating Podocyte Injury in Diabetic Nephropathy. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2023, 29, 3073–3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Xu, C.; Huang, J.; Xu, C.; Xiong, Y. Astragalus Polysaccharide Attenuates Diabetic Nephropathy by Reducing Apoptosis and Enhancing Autophagy through Activation of Sirt1/FoxO1 Pathway. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2024, 56, 3067–3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Wang, Q.; Shi, G.; Yang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, W.; Wan, S.; Xiong, F.; Wang, Z. Emodin Ameliorates Renal Damage and Podocyte Injury in a Rat Model of Diabetic Nephropathy via Regulating AMPK/mTOR-Mediated Autophagy Signaling Pathway. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2021, 14, 1253–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, H.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Mao, W.; Liu, X.; Zhang, L. Kaempferol Attenuated Diabetic Nephropathy by Reducing Apoptosis and Promoting Autophagy through AMPK/mTOR Pathways. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 986825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khodir, S.A.; Samaka, R.M.; Ameen, O. Autophagy and mTOR Pathways Mediate the Potential Renoprotective Effects of Vitamin D on Diabetic Nephropathy. Int. J. Nephrol. 2020, 2020, 7941861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Dai, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, H. Yiqi Huoxue Recipe Regulates Autophagy through Degradation of Advanced Glycation End Products via mTOR/S6K1/LC3 Pathway in Diabetic Nephropathy. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. ECAM 2021, 2021, 9942678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusabimana, T.; Park, E.J.; Je, J.; Jeong, K.; Yun, S.P.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, H.; Park, S.W. Geniposide Improves Diabetic Nephropathy by Enhancing ULK1-Mediated Autophagy and Reducing Oxidative Stress through AMPK Activation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, L.; Xu, X.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Niu, X.; Hu, A. Tangshen Decoction Enhances Podocytes Autophagy to Relieve Diabetic Nephropathy through Modulation of P-AMPK/p-ULK1 Signaling. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. ECAM 2022, 2022, 3110854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, D.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Guan, F.; Zhang, M.; Chen, L. Highly Bioavailable Berberine Formulation Ameliorates Diabetic Nephropathy through the Inhibition of Glomerular Mesangial Matrix Expansion and the Activation of Autophagy. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 873, 172955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wu, T.; Li, H.; Liu, M.; Xu, H. Tanshinone IIA Promoted Autophagy and Inhibited Inflammation to Alleviate Podocyte Injury in Diabetic Nephropathy. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2024, 17, 2709–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Qu, Q.; Zhao, C.; Liu, X.; Yang, P.; Li, Z.; Han, L.; Shi, X. Paecilomyces Cicadae-Fermented Radix Astragali Activates Podocyte Autophagy by Attenuating PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathways to Protect against Diabetic Nephropathy in Mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 129, 110479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, Y.; Fu, C.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, M.; Xie, H.; Tong, X.; Li, Y.; Hou, Z.; Fan, X.; Yan, M. Celastrol Slows the Progression of Early Diabetic Nephropathy in Rats via the PI3K/AKT Pathway. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- QTu, Q.; Li, Y.; Jin, J.; Jiang, X.; Ren, Y.; He, Q. Curcumin Alleviates Diabetic Nephropathy via Inhibiting Podocyte Mesenchymal Transdifferentiation and Inducing Autophagy in Rats and MPC5 Cells. Pharm. Biol. 2019, 57, 778–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Fang, J.; Zhang, J.; Ding, S.; Gan, D. Curcumin Inhibited Podocyte Cell Apoptosis and Accelerated Cell Autophagy in Diabetic Nephropathy via Regulating Beclin1/UVRAG/Bcl2. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2020, 13, 641–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Z.; Xiao, M.; Wang, B.; Zhang, W.; Che, K.; Lv, W.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Renoprotective Effect of Isoorientin in Diabetic Nephropathy via Activating Autophagy and Inhibiting the PI3K-AKT-TSC2-mTOR Pathway. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2023, 51, 1269–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-Z.; Jiang, H.; Xu, L.; Liu, Y.-Q.; Tang, J.-W.; Shi, J.-S.; Yu, X.-J.; Wang, X.; Du, L.; Lu, Q.; et al. Sarsasapogenin Restores Podocyte Autophagy in Diabetic Nephropathy by Targeting GSK3β Signaling Pathway. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2021, 192, 114675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, L.; Shi, J.; Yu, X.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Jiang, H.; Yang, T.; Yin, X.; et al. Quercetin Attenuates Podocyte Apoptosis of Diabetic Nephropathy Through Targeting EGFR Signaling. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 792777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Fang, J.; Ju, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Xing, L.; Cao, A. Zuogui Wan Ameliorates High Glucose-Induced Podocyte Apoptosis and Improves Diabetic Nephropathy in Db/Db Mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 991976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Bai, Y.; Yu, N.; Lu, B.; Han, G.; Yin, C.; Pang, Z. Huidouba Improved Podocyte Injury by Down-Regulating Nox4 Expression in Rats With Diabetic Nephropathy. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 587995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Li, R.; Zhao, L.; Ma, S.; Qin, G. Resveratrol Ameliorates Renal Damage by Inhibiting Oxidative Stress-Mediated Apoptosis of Podocytes in Diabetic Nephropathy. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 885, 173387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F.-Q.; Tang, L.; Gao, Y.-B.; Wang, Y.-F.; Meng, Y.; Shen, C.; Shen, Z.-L.; Liu, Z.-Q.; Zhao, W.-J.; Liu, W.J. Effect of Baoshenfang Formula on Podocyte Injury via Inhibiting the NOX-4/ROS/P38 Pathway in Diabetic Nephropathy. J. Diabetes Res. 2019, 2019, 2981705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Ling, Y.; Yin, S.; Yang, S.; Kong, M.; Li, Z. Baicalin Serves a Protective Role in Diabetic Nephropathy through Preventing High Glucose-Induced Podocyte Apoptosis. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Sun, S.-C. NF-κB in Inflammation and Renal Diseases. Cell Biosci. 2015, 5, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afonina, I.S.; Zhong, Z.; Karin, M.; Beyaert, R. Limiting Inflammation—The Negative Regulation of NF-κB and the NLRP3 Inflammasome. Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Kang, J.; Yang, Z.; Ma, L.; Ma, L.; et al. Coptisine Mitigates Diabetic Nephropathy via Repressing the NRLP3 Inflammasome. Open Life Sci. 2023, 18, 20220568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Zhou, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, F.; Liu, M. Silibinin Attenuates High-Fat Diet-Induced Renal Fibrosis of Diabetic Nephropathy. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2019, 13, 3117–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.; Li, D.; Zhang, S.; Ikejima, T.; Jia, Y.; Wang, D.; Xu, F. Role of Silibinin in the Management of Diabetes Mellitus and Its Complications. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2018, 41, 785–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; He, Y.; Fang, Q.; Xie, G.; Qi, M. Ferulic Acid Ameliorates Renal Injury via Improving Autophagy to Inhibit Inflammation in Diabetic Nephropathy Mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 153, 113424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, S.; Jiang, S.-S.; Li, R.; Tian, B.; Huang, C.-Y.; Wang, R.; Li, Y.-Y.; Zhu, H.; Yuan, Y.-F.; Hu, X. Hong Guo Ginseng Guo (HGGG) Protects against Kidney Injury in Diabetic Nephropathy by Inhibiting NLRP3 Inflammasome and Regulating Intestinal Flora. Phytomed. Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2024, 132, 155861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Jing, M.; Liu, Q. Crocin Alleviates the Inflammation and Oxidative Stress Responses Associated with Diabetic Nephropathy in Rats via NLRP3 Inflammasomes. Life Sci. 2021, 278, 119542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; Zhu, L.; Wang, S.; Guo, X.; Sun, B.; Wang, Q.; Chen, L. Berberine Protects Diabetic Nephropathy by Suppressing Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Involving the Inactivation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome. Ren. Fail. 2022, 44, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.-W.; Hao, Y.-C.; Chen, Y.-J.; Yin, S.-Y.; Zhang, M.-Y.; Kong, L.; Wang, T.Y. Protective Effects of Sarsasapogenin against Early Stage of Diabetic Nephropathy in Rats. Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.-Z.; Zhang, Y.-M.; Zheng, T.; Huang, T.-T.; Ma, T.-F.; Liu, Y.-W. Sarsasapogenin Alleviates Diabetic Nephropathy through Suppression of Chronic Inflammation by Down-Regulating PAR-1: In Vivo and in Vitro Study. Phytomed. Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2020, 78, 153314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Zhou, X.; Bao, X.; Zhang, J.; Tang, J.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, N.; Bai, Y.; Xi, Y.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Dioscorea zingiberensis Ameliorates Diabetic Nephropathy by Inhibiting NLRP3 Inflammasome and Curbing the Expression of p66Shc in High-Fat Diet/Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Mice. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2021, 73, 1218–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.-J.; Park, J.-H.; Lee, Y.-J.; Kim, H.-Y.; Han, B.-H.; Jin, H.-G.; Kang, D.-G.; Lee, H.-S. Protective Effects of Ethanolic Extract from Rhizome of Polygoni Avicularis against Renal Fibrosis and Inflammation in a Diabetic Nephropathy Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, S.; Bai, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, W. Thonningianin a Ameliorated Renal Interstitial Fibrosis in Diabetic Nephropathy Mice by Modulating Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis and Repressing Inflammation. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1389654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Tan, J.; Zhao, J.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Dai, X.; Sun, Y.; Kuang, Q.; Hui, J.; Chen, J.; et al. Cynapanoside a Exerts Protective Effects against Obesity-Induced Diabetic Nephropathy through Ameliorating TRIM31-Mediated Inflammation, Lipid Synthesis and Fibrosis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 113, 109395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboismaiel, M.G.; Amin, M.N.; Eissa, L.A. Renoprotective Effect of a Novel Combination of 6-Gingerol and Metformin in High-Fat Diet/Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Nephropathy in Rats via Targeting miRNA-146a, miRNA-223, TLR4/TRAF6/NLRP3 Inflammasome Pathway and HIF-1α. Biol. Res. 2024, 57, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xie, N.; Feng, L.; Huang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Tang, J.; Zhang, Y. Oxidative Stress in Diabetes Mellitus and Its Complications: From Pathophysiology to Therapeutic Strategies. Chin. Med. J. 2025, 138, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Wang, L.; Wu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Yao, Y.; Yang, H.; Hao, C. Lipid Metabolism in Ferroptosis: Mechanistic Insights and Therapeutic Potential. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1545339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, P.; Xing, C.; Zhao, J.; He, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, A.; Lin, H.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Abelmoschus manihot for Primary Glomerular Disease: A Prospective, Multicenter Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Am. J. Kidney Dis. Off. J. Natl. Kidney Found. 2014, 64, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, T.; Zhang, X.; Xie, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Tang, C.; Yang, Y.; Sun, J.; Gao, J.; Yu, T.; et al. Natural Compounds Efficacy in Complicated Diabetes: A New Twist Impacting Ferroptosis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 168, 115544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, S.; Hazra, R.; Mallick, A.; Gayen, S.; Roy, S. A Review on Comprehending Immunotherapeutic Approaches Inducing Ferroptosis: Managing Tumour Immunity. Immunology 2024, 172, 547–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanase, D.M.; Gosav, E.M.; Anton, M.I.; Floria, M.; Seritean Isac, P.N.; Hurjui, L.L.; Tarniceriu, C.C.; Costea, C.F.; Ciocoiu, M.; Rezus, C. Oxidative Stress and NRF2/KEAP1/ARE Pathway in Diabetic Kidney Disease (DKD): New Perspectives. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Zhang, J.; Luo, L.; Hu, J. Protective Effects of Xanthohumol against Diabetic Nephropathy in a Mouse Model. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2023, 48, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LMa, L.; Wu, F.; Shao, Q.; Chen, G.; Xu, L.; Lu, F. Baicalin Alleviates Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Diabetic Nephropathy via Nrf2 and MAPK Signaling Pathway. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2021, 15, 3207–3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forcina, G.C.; Dixon, S.J. GPX4 at the Crossroads of Lipid Homeostasis and Ferroptosis. Proteomics 2019, 19, e1800311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, S.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y. Vitexin Ameliorated Diabetic Nephropathy via Suppressing GPX4-Mediated Ferroptosis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 951, 175787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Niu, H.; Bian, M.; Zhu, C. Kidney Tea [Orthosiphon aristatus (Blume) Miq.] Improves Diabetic Nephropathy via Regulating Gut Microbiota and Ferroptosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1392123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhou, R. NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation and Cell Death. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2021, 18, 2114–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Zhai, Y.; Liang, S.; Mori, Y.; Han, R.; Sutterwala, F.S.; Qiao, L. TRPM2 Links Oxidative Stress to NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, K.; Chen, X.; Zhu, X. Leonurine Ameliorates Diabetic Nephropathy through GPX4-Mediated Ferroptosis of Endothelial Cells. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed.) 2024, 29, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.-Y.; Peng, G.-C.; Han, Q.-T.; Yan, J.; Chen, L.-Z.; Wang, T.; Xu, L.-T.; Liu, M.-J.; Xu, Z.-P.; Wang, X.-N.; et al. Phthalides from the Rhizome of Ligusticum chuanxiong Hort. Attenuate Diabetic Nephropathy in Mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 319, 117247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherkhane, B.; Yerra, V.G.; Sharma, A.; Kumar, A.K.; Chayanika, G.; Kumar, A.V.; Kumar, A. Nephroprotective Potential of Syringic Acid in Experimental Diabetic Nephropathy: Focus on Oxidative Stress and Autophagy. Indian. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 55, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A AlMousa, L.; A AlFaris, N.; Alshammari, G.M.; Alsayadi, M.M.; Altamimi, J.Z.; I Alagal, R.; Yahya, M.A. Rumex nervosus Could Alleviate Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Nephropathy in Rats by Activating Nrf2 Signaling. Sci. Prog. 2022, 105, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlTamimi, J.Z.; AlFaris, N.A.; Alshammari, G.M.; Alagal, R.I.; Aljabryn, D.H.; Yahya, M.A. Protective Effect of Eriodictyol against Hyperglycemia-Induced Diabetic Nephropathy in Rats Entails Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects Mediated by Activating Nrf2. Saudi Pharm. J. SPJ Off. Publ. Saudi Pharm. Soc. 2023, 31, 101817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Chang, L.; Ren, Y.; Sui, M.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Hao, L. Quercetin Improves Diabetic Kidney Disease by Inhibiting Ferroptosis and Regulating the Nrf2 in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. Ren. Fail. 2024, 46, 2327495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Qi, S.; Song, Y.; Ling, C. Artemisinin Attenuates Early Renal Damage on Diabetic Nephropathy Rats through Suppressing TGF-Β1 Regulator and Activating the Nrf2 Signaling Pathway. Life Sci. 2020, 256, 117966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, L.; Gong, Y.; Xu, W.; Dao, J.; Rao, J.; Yang, H. Chlorogenic Acid Inhibits NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation through Nrf2 Activation in Diabetic Nephropathy. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0316615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Ouyang, D.; Liu, Q. Isoeucommin a Attenuates Kidney Injury in Diabetic Nephropathy through the Nrf2/HO-1 Pathway. FEBS Open Bio 2021, 11, 2350–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Chen, C. Umbelliferone Delays the Progression of Diabetic Nephropathy by Inhibiting Ferroptosis through Activation of the Nrf-2/HO-1 Pathway. Food Chem. Toxicol. Int. J. Publ. Br. Ind. Biol. Res. Assoc. 2022, 163, 112892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, L.; Cao, P.; Wang, H. Tetrandrine Mediates Renal Function and Redox Homeostasis in a Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Nephropathy Rat Model through Nrf2/HO-1 Reactivation. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaofi, A.L. Sinapic Acid Ameliorates the Progression of Streptozotocin (STZ)-Induced Diabetic Nephropathy in Rats via NRF2/HO-1 Mediated Pathways. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Huang, Q.; Liu, R.; Liu, J.; Zhang, F.; Liu, S.; Jiang, Y. Moringa oleifera Lam. Seed Extract Protects Kidney Function in Rats with Diabetic Nephropathy by Increasing GSK-3β Activity and Activating the Nrf2/HO-1 Pathway. Phytomed. Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2022, 95, 153856, Erratum in Phytomed. Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2022, 100, 154043.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, L.-G.; Zhang, R.; Jin, G.-X.; Pei, X.-Y.; Wang, Q.; Ge, X.-X. Asiaticoside Improves Diabetic Nephropathy by Reducing Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Fibrosis: An in Vitro and in Vivo Study. World J. Diabetes 2024, 15, 2111–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, A.S. Kaempferol Attenuates Diabetic Nephropathy in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats by a Hypoglycaemic Effect and Concomitant Activation of the Nrf-2/Ho-1/Antioxidants Axis. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 129, 984–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Yang, M.; Li, T.; Wang, D.; Li, Y.; Tang, X.; Yuan, L.; Gu, S.; Xu, Y. Neferine Inhibits the Progression of Diabetic Nephropathy by Modulating the miR-17-5p/Nuclear Factor E2-Related Factor 2 Axis. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2024, 44, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Huang, L.; Liu, Q.; Ouyang, D. Eucommia Lignans Alleviate the Progression of Diabetic Nephropathy through Mediating the AR/Nrf2/HO-1/AMPK Axis in Vivo and in Vitro. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2023, 21, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, D.; Ying, Z.; Yang, Y.; Qian, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, P.; An, X.; Yan, M. Deciphering the Anti-Renal Fibrosis Mechanism of Triptolide in Diabetic Nephropathy by the Integrative Approach of Network Pharmacology and Experimental Verification. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 316, 116774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, C.; Cheng, T.; Zhang, B.; Sun, K.; Lu, K. Triptolide Protects against Podocyte Injury in Diabetic Nephropathy by Activating the Nrf2/HO-1 Pathway and Inhibiting the NLRP3 Inflammasome Pathway. Ren. Fail. 2023, 45, 2165103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Fan, D.; Guo, F.; Deng, J.; Fu, L. The Effect of Moringa Isothiocyanate-1 on Renal Damage in Diabetic Nephropathy. Iran. J. Kidney Dis. 2023, 17, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mohan, T.; Narasimhan, K.K.S.; Ravi, D.B.; Velusamy, P.; Chandrasekar, N.; Chakrapani, L.N.; Srinivasan, A.; Karthikeyan, P.; Kannan, P.; Tamilarasan, B.; et al. Role of Nrf2 Dysfunction in the Pathogenesis of Diabetic Nephropathy: Therapeutic Prospect of Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 160, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.; Zhang, W. Obacunone Inhibits Ferroptosis through Regulation of Nrf2 Homeostasis to Treat Diabetic Nephropathy. Mol. Med. Rep. 2025, 31, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Fan, L.; Chen, X.; Su, X.; Dong, L.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Cui, H.; Zhang, S.; et al. Jian-Pi-Gu-Shen-Hua-Yu Decoction Alleviated Diabetic Nephropathy in Mice through Reducing Ferroptosis. J. Diabetes Res. 2024, 2024, 9990304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, D.; Hu, W.; Han, X.; Cai, Y. Rhein Inhibited Ferroptosis and EMT to Attenuate Diabetic Nephropathy by Regulating the Rac1/NOX1/β-Catenin Axis. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed.) 2023, 28, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Li, H.; Zhang, T.; Su, X.; Sun, W.; Wang, Q.; Wang, L.; Feng, N.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; et al. San-Huang-Yi-Shen Capsule Ameliorates Diabetic Nephropathy in Mice through Inhibiting Ferroptosis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 165, 115086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; He, X.; Xue, M.; Sun, W.; He, Q.; Jin, J. Germacrone Protects Renal Tubular Cells against Ferroptotic Death and ROS Release by Re-Activating Mitophagy in Diabetic Nephropathy. Free Radic. Res. 2023, 57, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Kang, Z.; Zhang, F. Tanshinone IIA Suppresses Ferroptosis to Attenuate Renal Podocyte Injury in Diabetic Nephropathy through the Embryonic Lethal Abnormal Visual-like Protein 1 and Acyl-Coenzyme a Synthetase Long-Chain Family Member 4 Signaling Pathway. J. Diabetes Investig. 2024, 15, 1003–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Li, Q.; Sui, B.; Xu, M.; Pu, Z.; Qiu, T. Schisandrin A from Schisandra chinensis Attenuates Ferroptosis and NLRP3 Inflammasome-Mediated Pyroptosis in Diabetic Nephropathy through Mitochondrial Damage by AdipoR1 Ubiquitination. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2022, 2022, 5411462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, H.; Zhang, M.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Z. Traditional Chinese Medicine Targeting the TGF-β/Smad Signaling Pathway as a Potential Therapeutic Strategy for Renal Fibrosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1513329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, W.; Qian, C.; Xu, F.; Cheng, P.; Yang, C.; Li, X.; Lu, Y.; Wang, A. Fuxin Granules Ameliorate Diabetic Nephropathy in Db/Db Mice through TGF-Β1/Smad and VEGF/VEGFR2 Signaling Pathways. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 141, 111806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.-X.; Liu, Y.; Xu, S.-S.; Yang, R.; Jiang, C.-H.; Zhu, L.-P.; Xu, Y.-Y.; Pan, K.; Zhang, J.; Yin, Z.-Q. Asiatic Acid from Cyclocarya paliurus Regulates the Autophagy-Lysosome System via Directly Inhibiting TGF-β Type I Receptor and Ameliorates Diabetic Nephropathy Fibrosis. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 5536–5546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Su, Q.; Geng, J.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Shi, Y.; Zou, Y. Ginkgo biloba Leaf Extract Prevents Diabetic Nephropathy through the Suppression of Tissue Transglutaminase. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 21, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Zeng, J.; Yu, X.; Shi, Y.; Song, N.; Zhang, J.; Wang, P.; Luo, M.; Ma, Y.; Xiao, C.; et al. Luteolin Alleviates Diabetic Nephropathy Fibrosis Involving AMPK/NLRP3/TGF-β Pathway. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2024, 17, 2855–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Han, R.; Tan, H.; Zhu, W.; Li, Y.; Jiang, F.; Xie, C.; Ren, Z.; Shi, R. Scutellarin Ameliorates Diabetic Nephropathy via TGF-Β1 Signaling Pathway. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect 2024, 14, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Yang, Y.; Sun, X.; Meng, H.; Hao, W.; Yin, J.; Ma, F.; Guo, X.; Du, L.; Sun, L.; et al. Krill Oil Turns Off TGF-Β1 Profibrotic Signaling in the Prevention of Diabetic Nephropathy. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 9865–9876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lin, X.; Zheng, Y.; Yu, W.; Lin, F.; Zhang, J. Dendrobium Mixture Ameliorates Diabetic Nephropathy in Db/Db Mice by Regulating the TGF-β 1/Smads Signaling Pathway. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 9931983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, H.; Wan, Z.; Wang, R.; Liu, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Guo, H.; et al. The Combination of Ursolic Acid and Empagliflozin Relieves Diabetic Nephropathy by Reducing Inflammation, Oxidative Stress and Renal Fibrosis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 144, 112267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Xiao, X.; Zheng, J.; Li, M.; Yu, M.; Ping, F.; Wang, T.; Wang, X. Qishen Yiqi Dripping Pill Protects against Diabetic Nephropathy by Inhibiting the Wnt/β-Catenin and Transforming Growth Factor-β/Smad Signaling Pathways in Rats. Front. Physiol. 2021, 11, 613324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Su, J.; Liu, Y.; Gao, T.; Ji, X.; Li, H.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Lv, S. Crocin Ameliorates Diabetic Nephropathy through Regulating Metabolism, CYP4A11/PPARγ, and TGF-β/Smad Pathways in Mice. Curr. Drug Metab. 2023, 24, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Wang, Q.; Ju, J.; Li, Y.; Cai, Q.; Hao, L.; Zhou, Y. Magnoflorine Ameliorates Inflammation and Fibrosis in Rats with Diabetic Nephropathy by Mediating the Stability of Lysine-Specific Demethylase 3A. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 580406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ural, C.; Celik, A.; Ozbal, S.; Guneli, E.; Arslan, S.; Ergur, B.U.; Cavdar, C.; Akdoğan, G.; Cavdar, Z. The Renoprotective Effects of Taurine against Diabetic Nephropathy via the P38 MAPK and TGF-β/Smad2/3 Signaling Pathways. Amino Acids 2023, 55, 1665–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.X.; Qi, S.S.; He, J.; Hu, C.Y.; Han, H.; Jiang, H.; Li, X.S. Cyanidin-3-Glucoside from Black Rice Ameliorates Diabetic Nephropathy via Reducing Blood Glucose, Suppressing Oxidative Stress and Inflammation, and Regulating Transforming Growth Factor Β1/Smad Expression. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 4399–4410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Wang, Y.; Piao, Y.; Rao, X.; Yin, D. Chrysophanol Inhibits the Progression of Diabetic Nephropathy via Inactivation of TGF-β Pathway. Drug Des. Devel Ther. 2020, 14, 4951–4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, L.-Y.; Sun, Y.; Tang, H.-T.; Xu, Z.-X. Huangkui Capsule in Combination with Metformin Ameliorates Diabetic Nephropathy via the Klotho/TGF-Β1/p38MAPK Signaling Pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 281, 113548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, W.; Tang, S.; Xiao, X.; Luo, S.; Yang, Z.; Huang, W.; Tang, S. Translation Animal Models of Diabetic Kidney Disease: Biochemical and Histological Phenotypes, Advantages and Limitations. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2023, 16, 1297–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, C.; Xu, Z.; Hou, J. Network Pharmacology and Molecular Docking Technology-Based Predictive Study of the Active Ingredients and Potential Targets of Rhubarb for the Treatment of Diabetic Nephropathy. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2022, 22, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selby-Pham, S.N.B.; Miller, R.B.; Howell, K.; Dunshea, F.; Bennett, L.E. Physicochemical Properties of Dietary Phytochemicals Can Predict Their Passive Absorption in the Human Small Intestine. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Zhao, L.; Huang, Y.; Fu, X.; Luo, R.; Xue, J.; Yang, S.; Ling, L.; et al. Nanoparticles Loaded with Pharmacologically Active Plant-Derived Natural Products: Biomedical Applications and Toxicity. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2023, 225, 113214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhao, B.; Yang, L.; Dong, X.; Yang, X.; Mao, Y. Demethylzeylasteral Reduces the Level of Proteinuria in Diabetic Nephropathy: Screening of Network Pharmacology and Verification by Animal Experiment. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2022, 10, e00976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Erviti, L.; Seow, Y.; Yin, H.; Betts, C.; Lakhal, S.; Wood, M.J.A. Delivery of siRNA to the Mouse Brain by Systemic Injection of Targeted Exosomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, J.K.; Das, G.; Fraceto, L.F.; Campos, E.V.R.; Rodriguez-Torres, M.D.P.; Acosta-Torres, L.S.; Diaz-Torres, L.A.; Grillo, R.; Swamy, M.K.; Sharma, S.; et al. Nano Based Drug Delivery Systems: Recent Developments and Future Prospects. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2018, 16, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uppal, S.; Italiya, K.S.; Chitkara, D.; Mittal, A. Nanoparticulate-Based Drug Delivery Systems for Small Molecule Anti-Diabetic Drugs: An Emerging Paradigm for Effective Therapy. Acta Biomater. 2018, 81, 20–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutia, G.T.; De, A.K.; Bhowmik, M.; Bera, T. Shellac and Locust Bean Gum Coacervated Curcumin, Epigallocatechin Gallate Nanoparticle Ameliorates Diabetic Nephropathy in a Streptozotocin-Induced Mouse Model. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 271, 132369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Du, X.; Fu, M.; Khan, A.R.; Ji, J.; Liu, W.; Zhai, G. Galactosamine-Modified PEG-PLA/TPGS Micelles for the Oral Delivery of Curcumin. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 595, 120227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostami, N.; Davarnejad, R. Characterization of Folic Acid-functionalized PLA–PEG Nanomicelle to Deliver Letrozole: A Nanoinformatics Study. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 16, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, F.; Hu, K.; Yu, H.; Zhou, L.; Song, L.; Zhang, Y.; Shan, X.; Liu, J.; Gu, N. A Functional Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Modified with PLA-PEG-DG as Tumor-Targeted MRI Contrast Agent. Pharm. Res. 2017, 34, 1683–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulkkinen, M.; Pikkarainen, J.; Wirth, T.; Tarvainen, T.; Haapa-aho, V.; Korhonen, H.; Seppälä, J.; Järvinen, K. Three-Step Tumor Targeting of Paclitaxel Using Biotinylated PLA-PEG Nanoparticles and Avidin-Biotin Technology: Formulation Development and in Vitro Anticancer Activity. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. Off. J. Arbeitsgemeinschaft Fur Pharm. Verfahrenstechnik E.V 2008, 70, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, J. Exosome-like Nanoparticles from Ginger Rhizomes Inhibited NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16, 2690–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Li, H.; Xu, G.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Tian, K. Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives of Exosomes as Nanocarriers in Diagnosis and Treatment of Diseases. Int. J. Nanomed. 2023, 18, 4751–4778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Han, X.; Li, C.; Sun, T.; Li, K.; Liu, X.; Liu, M. The Status of Industrialization and Development of Exosomes as a Drug Delivery System: A Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 961127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Zhuang, X.; Xiang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, C.; Barnes, S.; Grizzle, W.; Miller, D.; Zhang, H.-G. A Novel Nanoparticle Drug Delivery System: The Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Curcumin Is Enhanced When Encapsulated in Exosomes. Mol. Ther. 2010, 18, 1606–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, D.A.; Miller, D.A.; Santitewagun, S.; Zeitler, J.A.; Su, Y.; Williams, R.O. Formulating a Heat- and Shear-Labile Drug in an Amorphous Solid Dispersion: Balancing Drug Degradation and Crystallinity. Int. J. Pharm. X 2021, 3, 100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binaymotlagh, R.; Hajareh Haghighi, F.; Chronopoulou, L.; Palocci, C. Liposome-Hydrogel Composites for Controlled Drug Delivery Applications. Gels 2024, 10, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, M.; Kluppel, A.C.; Wartna, E.S.; Moolenaar, F.; Meijer, D.K.; de Jong, P.E.; de Zeeuw, D. Drug-Targeting to the Kidney: Renal Delivery and Degradation of a Naproxen-Lysozyme Conjugate in Vivo. Kidney Int. 1997, 52, 1693–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; He, W.; Ren, P.; Zhao, L.; Zheng, D.; Jin, J. Carthamin Yellow-Loaded Glycyrrhetinic Acid Liposomes Alleviate Interstitial Fibrosis in Diabetic Nephropathy. Ren. Fail. 2025, 47, 2459356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.-P.; Nie, Q.; Feng, J.; Fan, X.-Y.; Jin, Y.-L.; Chen, G.; Du, J.-W. Kidney-Targeted Baicalin-Lysozyme Conjugate Ameliorates Renal Fibrosis in Rats with Diabetic Nephropathy Induced by Streptozotocin. BMC Nephrol. 2020, 21, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, L.; Fan, W.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Peng, W.; Wu, C. The Application of Fermentation Technology in Traditional Chinese Medicine: A Review. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2020, 48, 899–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yñigez-Gutierrez, A.E.; Bachmann, B.O. Fixing the Unfixable: The Art of Optimizing Natural Products for Human Medicine. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 8412–8428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.; Yang, F.; Li, Z.; Qu, Q.; Zhao, C.; Liu, X.; Yang, P.; Han, L.; Shi, Y.; Shi, X. Paecilomyces cicadae-Fermented Radix astragali Ameliorate Diabetic Nephropathy in Mice by Modulating the Gut Microbiota. J. Med. Microbiol. 2022, 71, 001535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Liu, D.; Liu, Y.; Tang, J.; Zhao, H.; Chen, X.; Tian, G.; Liu, G.; Cai, J.; Jia, G. The Microbiota and Metabolome Dynamics and Their Interactions Modulate Solid-State Fermentation Process and Enhance Clean Recycling of Brewers’ Spent Grain. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1438878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lai, Z.; Huang, J.; Li, C.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, X.; Deng, J.; Ye, X.; Li, X. An Integrated Network Pharmacology and Transcriptomic Method to Explore the Mechanism of the Total Rhizoma Coptidis Alkaloids in Improving Diabetic Nephropathy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 270, 113806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]