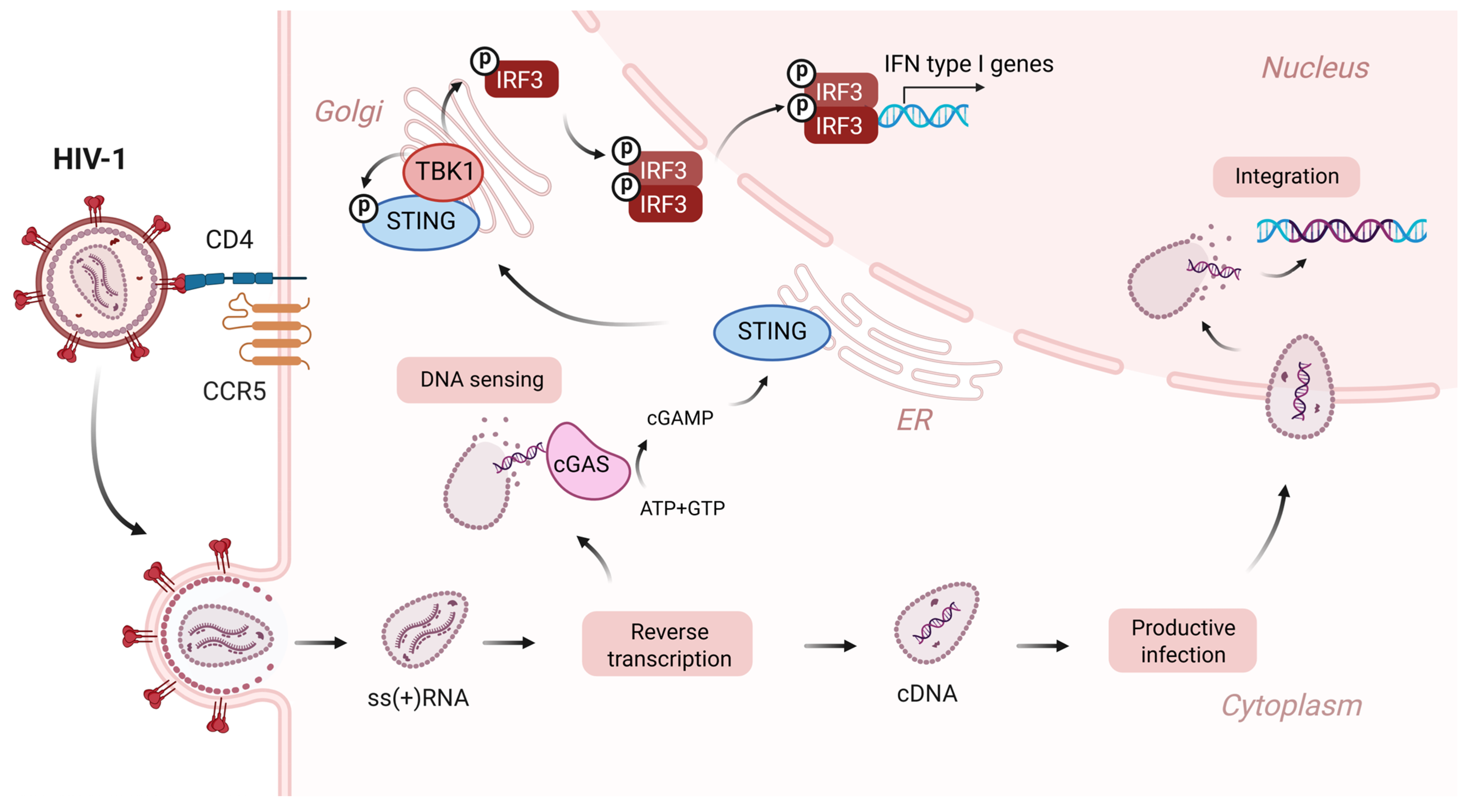

HIV-1 and Its Strategy for Hiding Viral cDNA from STING-Mediated Innate Immunity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. cGAS-STING Pathway in HIV-1 Patients

3. HIV-1 Capsid and Reverse Transcription: Balance Is the Key

4. Host Factors Involved in HIV-1 Innate Sensing

5. Viral Proteins Contribute to Attenuating cGAS-STING Activation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, L.; Wu, J.; Du, F.; Chen, X.; Chen, Z.J. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. Science 2013, 339, 786–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Sun, L.; Chen, X.; Du, F.; Shi, H.; Chen, C.; Chen, Z.J. Cyclic GMP-AMP is an endogenous second messenger in innate immune signaling by cytosolic DNA. Science 2013, 339, 826–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, J.; Du, F.; Xu, H.; Sun, L.; Chen, Z.; Brautigam, C.A.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Z.J. The cytosolic DNA sensor cGAS forms an oligomeric complex with DNA and undergoes switch-like conformational changes in the activation loop. Cell Rep. 2014, 6, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa, H.; Barber, G.N. STING is an endoplasmic reticulum adaptor that facilitates innate immune signalling. Nature 2008, 455, 674–678, Erratum in Nature 2008, 456, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Shang, G.; Gui, X.; Zhang, X.; Bai, X.-C.; Chen, Z.J. Structural basis of STING binding with and phosphorylation by TBK1. Nature 2019, 567, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Chen, Z.J. STING specifies IRF3 phosphorylation by TBK1 in the cytosolic DNA signaling pathway. Sci. Signal. 2012, 5, ra20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Cai, X.; Wu, J.; Cong, Q.; Chen, X.; Li, T.; Du, F.; Ren, J.; Wu, Y.T.; Grishin, N.V.; et al. Phosphorylation of innate immune adaptor proteins MAVS, STING, and TRIF induces IRF3 activation. Science 2015, 347, aaa2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Sun, L.; Chen, Z.J. Regulation and function of the cGAS-STING pathway of cytosolic DNA sensing. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 1142–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, H.; Ma, Z.; Barber, G.N. STING regulates intracellular DNA-mediated, type I interferon-dependent innate immunity. Nature 2009, 461, 788–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenson, J.M.; Chen, Z.J. cGAS goes viral: A conserved immune defense system from bacteria to humans. Mol. Cell 2024, 84, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepelley, A.; Louis, S.; Sourisseau, M.; Law, H.K.W.; Pothlichet, J.; Schilte, C.; Chaperot, L.; Plumas, J.; Randall, R.E.; Si-Tahar, M.; et al. Innate sensing of HIV-infected cells. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1001284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, D.; Wu, J.; Wu, Y.T.; Du, F.; Aroh, C.; Yan, N.; Sun, L.; Chen, Z.J. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is an innate immune sensor of HIV and other retroviruses. Science 2013, 341, 903–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakobsen, M.R.; Bak, R.O.; Andersen, A.; Berg, R.K.; Jensen, S.B.; Jin, T.; Laustsen, A.; Hansen, K.; Østergaard, L.; Fitzgerald, K.A.; et al. IFI16 senses DNA forms of the lentiviral replication cycle and controls HIV-1 replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E4571–E4580, Erratum in Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 19651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeire, J.; Roesch, F.; Sauter, D.; Rua, R.; Hotter, D.; Van Nuffel, A.; Vanderstraeten, H.; Naessens, E.; Iannucci, V.; Landi, A.; et al. HIV Triggers a cGAS-Dependent, Vpu- and Vpr-Regulated Type I Interferon Response in CD4+ T Cells. Cell Rep. 2016, 17, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes, C.A.C.; Oliveira, L.M.S.; Manfrere, K.C.G.; Lima, J.F.; Pereira, N.Z.; Duarte, A.J.S.; Sato, M.N. Antiviral factors and type I/III interferon expression associated with regulatory factors in the oral epithelial cells from HIV-1-serodiscordant couples. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, L.L.P.; de Oliveira, A.Q.T.; Moura, T.C.F.; da Silva Graça Amoras, E.; Lima, S.S.; da Silva, A.N.M.R.; Queiroz, M.A.F.; Cayres-Vallinoto, I.M.V.; Ishak, R.; Vallinoto, A.C.R. STING and cGAS gene expressions were downregulated among HIV-1-infected persons after antiretroviral therapy. Virol. J. 2021, 18, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, N.Z.; Cardoso, E.C.; Oliveira, L.M.D.S.; De Lima, J.F.; Branco, A.C.C.C.; Ruocco, R.M.D.S.A.; Zugaib, M.; Filho, J.B.D.O.; Duarte, A.J.D.S.; Sato, M.N. Upregulation of innate antiviral restricting factor expression in the cord blood and decidual tissue of HIV-infected mothers. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e84917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Urbano, V.; Bertoldi, A.; Re, M.C.; de Crignis, E.; Tamburello, M.; Primavera, A.; Laginestra, M.A.; Zanasi, N.; Calza, L.; Viale, P.L.; et al. Restriction Factors expression decreases in HIV-1 patients after cART. New Microbiol. 2021, 44, 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Blankson, J.N. Effector mechanisms in HIV-1 infected elite controllers: Highly active immune responses? Antivir. Res. 2010, 85, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Gayo, E.; Buzon, M.J.; Ouyang, Z.; Hickman, T.; Cronin, J.; Pimenova, D.; Walker, B.D.; Lichterfeld, M.; Yu, X.G. Potent Cell-Intrinsic Immune Responses in Dendritic Cells Facilitate HIV-1-Specific T Cell Immunity in HIV-1 Elite Controllers. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1004930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, S.K.; Pedersen, J.G.; Helleberg, M.; Kjær, K.; Thavachelvam, K.; Obel, N.; Tolstrup, M.; Jakobsen, M.R.; Mogensen, T.H. Multiple Homozygous Variants in the STING-Encoding TMEM173 Gene in HIV Long-Term Nonprogressors. J. Immunol. 2018, 200, 3372–3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosnefroy, O.; Murray, P.J.; Bishop, K.N. HIV-1 capsid uncoating initiates after the first strand transfer of reverse transcription. Retrovirology 2016, 13, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamede, J.I.; Cianci, G.C.; Anderson, M.R.; Hope, T.J. Early cytoplasmic uncoating is associated with infectivity of HIV-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E7169–E7178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankovic, S.; Varadarajan, J.; Ramalho, R.; Aiken, C.; Rousso, I. Reverse Transcription Mechanically Initiates HIV-1 Capsid Disassembly. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e00289-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, A.; Shi, J.; Rotem-Dai, N.; Aiken, C.; Rousso, I. Reverse transcription progression and genome length regulate HIV-1 core elasticity and disassembly. PLoS Pathog. 2025, 21, e1013269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Fricke, T.; Diaz-Griffero, F. Inhibition of reverse transcriptase activity increases stability of the HIV-1 core. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 683–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahaye, X.; Gentili, M.; Silvin, A.; Conrad, C.; Picard, L.; Jouve, M.; Zueva, E.; Maurin, M.; Nadalin, F.; Knott, G.J.; et al. NONO Detects the Nuclear HIV Capsid to Promote cGAS-Mediated Innate Immune Activation. Cell 2018, 175, 488–501.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arhel, N.J.; Souquere-Besse, S.; Munier, S.; Souque, P.; Guadagnini, S.; Rutherford, S.; Prévost, M.C.; Allen, T.D.; Charneau, P. HIV-1 DNA Flap formation promotes uncoating of the pre-integration complex at the nuclear pore. EMBO J. 2007, 26, 3025–3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdick, R.C.; Li, C.; Munshi, M.H.; Rawson, J.M.O.; Nagashima, K.; Hu, W.S.; Pathak, V.K. HIV-1 uncoats in the nucleus near sites of integration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 5486–5493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdick, R.C.; Morse, M.; Rouzina, I.; Williams, M.C.; Hu, W.S.; Pathak, V.K. HIV-1 uncoating requires long double-stranded reverse transcription products. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadn7033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zila, V.; Margiotta, E.; Turoňová, B.; Müller, T.G.; Zimmerli, C.E.; Mattei, S.; Allegretti, M.; Börner, K.; Rada, J.; Müller, B.; et al. Cone-shaped HIV-1 capsids are transported through intact nuclear pores. Cell 2021, 184, 1032–1046.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schifferdecker, S.; Zila, V.; Müller, T.G.; Sakin, V.; Anders-Össwein, M.; Laketa, V.; Kräusslich, H.G.; Müller, B. Direct Capsid Labeling of Infectious HIV-1 by Genetic Code Expansion Allows Detection of Largely Complete Nuclear Capsids and Suggests Nuclear Entry of HIV-1 Complexes via Common Routes. mBio 2022, 13, e01959-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.; Weiskopf, E.N.; Akkermans, O.; Swanson, N.A.; Cheng, S.; Schwartz, T.U.; Görlich, D. HIV-1 capsids enter the FG phase of nuclear pores like a transport receptor. Nature 2024, 626, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.E.; Ambrose, Z.; Martin, T.D.; Oztop, I.; Mulky, A.; Julias, J.G.; Vandegraaff, N.; Baumann, J.G.; Wang, R.; Yuen, W.; et al. Flexible Use of Nuclear Import Pathways by HIV-1. Cell Host Microbe 2010, 7, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.A.; Saito, A.; Halambage, U.D.; Ferhadian, D.; Fischer, D.K.; Francis, A.C.; Melikyan, G.B.; Ambrose, Z.; Aiken, C.; Yamashita, M. A Novel Phenotype Links HIV-1 Capsid Stability to cGAS-Mediated DNA Sensing. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e00706-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, R.P.; Harrison, L.; Touizer, E.; Peacock, T.P.; Spencer, M.; Zuliani-Alvarez, L.; Towers, G.J. Disrupting HIV-1 capsid formation causes cGAS sensing of viral DNA. EMBO J. 2020, 39, e103958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, R.P.; Blest, H.; Lin, M.; Maluquer de Motes, C.; Towers, G.J. HIV-1 with gag processing defects activates cGAS sensing. Retrovirology 2024, 21, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschbach, J.E.; Puray-Chavez, M.; Mohammed, S.; Wang, Q.; Xia, M.; Huang, L.C.; Shan, L.; Kutluay, S.B. HIV-1 capsid stability and reverse transcription are finely balanced to minimize sensing of reverse transcription products via the cGAS-STING pathway. mBio 2024, 15, e00348-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuliani-Alvarez, L.; Govasli, M.L.; Rasaiyaah, J.; Monit, C.; Perry, S.O.; Sumner, R.P.; McAlpine-Scott, S.; Dickson, C.; Rifat Faysal, K.M.; Hilditch, L.; et al. Evasion of cGAS and TRIM5 defines pandemic HIV. Nat. Microbiol. 2022, 7, 1762–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallery, D.L.; Márquez, C.L.; McEwan, W.A.; Dickson, C.F.; Jacques, D.A.; Anandapadamanaban, M.; Bichel, K.; Towers, G.J.; Saiardi, A.; Böcking, T.; et al. IP6 is an HIV pocket factor that prevents capsid collapse and promotes DNA synthesis. eLife 2018, 7, e35335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, G.; Albecka, A.; Mallery, D.; Vaysburd, M.; Renner, N.; James, L.C. IP6-stabilised HIV capsids evade cGAS/STING-mediated host immune sensing. EMBO Rep. 2023, 24, e56275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Kleinpeter, A.B.; Rey, J.S.; Shen, J.; Shen, Y.; Xu, J.; Hardenbrook, N.; Chen, L.; Lucic, A.; Perilla, J.R.; et al. Structural basis for HIV-1 capsid adaption to a deficiency in IP6 packaging. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 8152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasaiyaah, J.; Tan, C.P.; Fletcher, A.J.; Price, A.J.; Blondeau, C.; Hilditch, L.; Jacques, D.A.; Selwood, D.L.; James, L.C.; Noursadeghi, M.; et al. HIV-1 evades innate immune recognition through specific cofactor recruitment. Nature 2013, 503, 402–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahaye, X.; Satoh, T.; Gentili, M.; Cerboni, S.; Conrad, C.; Hurbain, I.; ElMarjou, A.; Lacabaratz, C.; Lelièvre, J.D.; Manel, N. The Capsids of HIV-1 and HIV-2 Determine Immune Detection of the Viral cDNA by the Innate Sensor cGAS in Dendritic Cells. Immunity 2013, 39, 1132–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, N.; Regalado-Magdos, A.D.; Stiggelbout, B.; Lee-Kirsch, M.A.; Lieberman, J. The cytosolic exonuclease TREX1 inhibits the innate immune response to human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 1005–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Morrison, J.H.; Dingli, D.; Poeschla, E. HIV-1 Activation of Innate Immunity Depends Strongly on the Intracellular Level of TREX1 and Sensing of Incomplete Reverse Transcription Products. J. Virol. 2018, 92, e00001-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stetson, D.B.; Ko, J.S.; Heidmann, T.; Medzhitov, R. Trex1 prevents cell-intrinsic initiation of autoimmunity. Cell 2008, 134, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstone, D.C.; Ennis-Adeniran, V.; Hedden, J.J.; Groom, H.C.T.; Rice, G.I.; Christodoulou, E.; Walker, P.A.; Kelly, G.; Haire, L.F.; Yap, M.W.; et al. HIV-1 restriction factor SAMHD1 is a deoxynucleoside triphosphate triphosphohydrolase. Nature 2011, 480, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahouassa, H.; Daddacha, W.; Hofmann, H.; Ayinde, D.; Logue, E.C.; Dragin, L.; Bloch, N.; Maudet, C.; Bertrand, M.; Gramberg, T.; et al. SAMHD1 restricts the replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by depleting the intracellular pool of deoxynucleoside triphosphates. Nat. Immunol. 2012, 13, 223–228, Erratum in Nat. Immunol. 2013, 14, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrecka, K.; Hao, C.; Gierszewska, M.; Swanson, S.K.; Kesik-Brodacka, M.; Srivastava, S.; Florens, L.; Washburn, M.P.; Skowronski, J. Vpx relieves inhibition of HIV-1 infection of macrophages mediated by the SAMHD1 protein. Nature 2011, 474, 658–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguette, N.; Sobhian, B.; Casartelli, N.; Ringeard, M.; Chable-Bessia, C.; Ségéral, E.; Yatim, A.; Emiliani, S.; Schwartz, O.; Benkirane, M. SAMHD1 is the dendritic- and myeloid-cell-specific HIV-1 restriction factor counteracted by Vpx. Nature 2011, 474, 654–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maelfait, J.; Bridgeman, A.; Benlahrech, A.; Cursi, C.; Rehwinkel, J. Restriction by SAMHD1 Limits cGAS/STING-Dependent Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses to HIV-1. Cell Rep. 2016, 16, 1492–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoh, S.M.; Schneider, M.; Seifried, J.; Soonthornvacharin, S.; Akleh, R.E.; Olivieri, K.C.; De Jesus, P.D.; Ruan, C.; De Castro, E.; Ruiz, P.A.; et al. PQBP1 is a proximal sensor of the cGAS-dependent innate response to HIV-1. Cell 2015, 161, 1293–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piacentini, J.; Allen, D.S.; Ganser-Pornillos, B.K.; Chanda, S.K.; Yoh, S.M.; Pornillos, O. Molecular Determinants of PQBP1 Binding to the HIV-1 Capsid Lattice. J. Mol. Biol. 2024, 436, 168409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoh, S.M.; Mamede, J.I.; Lau, D.; Ahn, N.; Sánchez-Aparicio, M.T.; Temple, J.; Tuckwell, A.; Fuchs, N.V.; Cianci, G.C.; Riva, L.; et al. Recognition of HIV-1 capsid by PQBP1 licenses an innate immune sensing of nascent HIV-1 DNA. Mol. Cell 2022, 82, 2871–2884.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.S.; Dang, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, G.; Wang, E.; Xia, H.; Zhou, W.; Wu, S.; Liu, X. The Hippo signaling component LATS2 enhances innate immunity to inhibit HIV-1 infection through PQBP1-cGAS pathway. Cell Death Differ. 2022, 29, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zierhut, C.; Yamaguchi, N.; Paredes, M.; Luo, J.D.; Carroll, T.; Funabiki, H. The Cytoplasmic DNA Sensor cGAS Promotes Mitotic Cell Death. Cell 2019, 178, 302–315.e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkman, H.E.; Cambier, S.; Gray, E.E.; Stetson, D.B. Tight nuclear tethering of cGAS is essential for preventing autoreactivity. eLife 2019, 8, e47491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Xu, P.; Rowlett, C.M.; Jing, T.; Shinde, O.; Lei, Y.; West, A.P.; Liu, W.R.; Li, P. The molecular basis of tight nuclear tethering and inactivation of cGAS. Nature 2020, 587, 673–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, C.; Bonnet-Madin, L.; Machida, S.; Sobhian, B.; Thenin-Houssier, S.; Benkirane, M. Unintegrated HIV-1 DNA recruits cGAS via its histone-binding domain to escape innate immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, 2424465122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unterholzner, L.; Keating, S.E.; Baran, M.; Horan, K.A.; Jensen, S.B.; Sharma, S.; Sirois, C.M.; Jin, T.; Latz, E.; Xiao, T.S.; et al. IFI16 is an innate immune sensor for intracellular DNA. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 997–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monroe, K.M.; Yang, Z.; Johnson, J.R.; Geng, X.; Doitsh, G.; Krogan, N.J.; Greene, W.C. IFI16 DNA sensor is required for death of lymphoid CD4 T cells abortively infected with HIV. Science 2014, 343, 428–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, R.K.; Rahbek, S.H.; Kofod-Olsen, E.; Holm, C.K.; Melchjorsen, J.; Jensen, D.G.; Hansen, A.L.; Jørgensen, L.B.; Ostergaard, L.; Tolstrup, M.; et al. T cells detect intracellular DNA but fail to induce type I IFN responses: Implications for restriction of HIV replication. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e84513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.; Kuffour, E.O.; Fuchs, N.V.; Gertzen, C.G.W.; Kaiser, J.; Hirschenberger, M.; Tang, X.; Xu, H.C.; Michel, O.; Tao, R.; et al. Regulation of STING activity in DNA sensing by ISG15 modification. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 113277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, C.B.; Bergstralh, D.T.; Duncan, J.A.; Lei, Y.; Morrison, T.E.; Zimmermann, A.G.; Accavitti-Loper, M.A.; Madden, V.J.; Sun, L.; Ye, Z.; et al. NLRX1 is a regulator of mitochondrial antiviral immunity. Nature 2008, 451, 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Cui, J.; Wang, H.Y.; Zhu, L.; Matsueda, S.; Wang, Q.; Yang, X.; Hong, J.; Songyang, Z.; Chen, Z.J.; et al. NLRX1 Negatively Regulates TLR-Induced NF-κB Signaling by Targeting TRAF6 and IKK. Immunity 2011, 34, 843–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; König, R.; Deng, M.; Riess, M.; Mo, J.; Zhang, L.; Petrucelli, A.; Yoh, S.M.; Barefoot, B.; Samo, M.; et al. NLRX1 Sequesters STING to Negatively Regulate the Interferon Response, Thereby Facilitating the Replication of HIV-1 and DNA Viruses. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 19, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, A.N.; Nasr, N.; Feetham, A.; Galoyan, A.; Alshehri, A.A.; Rambukwelle, D.; Botting, R.A.; Hiener, B.M.; Diefenbach, E.; Diefenbach, R.J.; et al. HIV Blocks Interferon Induction in Human Dendritic Cells and Macrophages by Dysregulation of TBK1. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 6575–6584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.; Sumner, R.P.; Rasaiyaah, J.; Tan, C.P.; Rodriguez-Plata, M.T.; Van Tulleken, C.; Fink, D.; Zuliani-Alvarez, L.; Thorne, L.; Stirling, D.; et al. HIV-1 Vpr antagonizes innate immune activation by targeting karyopherin-mediated NF-κB/IRF3 nuclear transport. eLife 2020, 9, e60821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotard, M.; Tsopoulidis, N.; Tibroni, N.; Willemsen, J.; Binder, M.; Ruggieri, A.; Fackler, O.T. Sensing of HIV-1 Infection in Tzm-bl Cells with Reconstituted Expression of STING. J. Virol. 2015, 90, 2064–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doehle, B.P.; Hladik, F.; McNevin, J.P.; McElrath, M.J.; Gale, M. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 mediates global disruption of innate antiviral signaling and immune defenses within infected cells. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 10395–10405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumura, A.; Alce, T.; Lubyova, B.; Ezelle, H.; Strebel, K.; Pitha, P.M. HIV-1 accessory proteins VPR and Vif modulate antiviral response by targeting IRF-3 for degradation. Virology 2008, 373, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobransky, A.; Root, M.; Hafner, N.; Marcum, M.; Sharifi, H.J. CRL4-DCAF1 Ubiquitin Ligase Dependent Functions of HIV Viral Protein R and Viral Protein X. Viruses 2024, 16, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doi, A.; Iijima, K.; Kano, S.; Ishizaka, Y. Viral protein R of HIV type-1 induces retrotransposition and upregulates glutamate synthesis by the signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 signaling pathway. Microbiol. Immunol. 2015, 59, 398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira Mann, C.C.; Orzalli, M.H.; King, D.S.; Kagan, J.C.; Lee, A.S.Y.; Kranzusch, P.J. Modular Architecture of the STING C-Terminal Tail Allows Interferon and NF-κB Signaling Adaptation. Cell Rep. 2019, 27, 1165–1175.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qian, G.; Zhu, L.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Han, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xiong, T.; Zeng, H.; et al. HIV-1 Vif suppresses antiviral immunity by targeting STING. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2022, 19, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Hu, M.M.; Wang, Y.Y.; Shu, H.B. TRIM32 protein modulates type I interferon induction and cellular antiviral response by targeting MITA/STING protein for K63-linked ubiquitination. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 28646–28655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, X.; Cui, Y.; Tang, Y.; Chen, W.; Li, S.; Yu, H.; Pan, Y.; Wang, C. The E3 Ubiquitin ligase AMFR and INSIG1 bridge the activation of TBK1 kinase by modifying the adaptor STING. Immunity 2014, 41, 919–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, G.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.; Xin, B.; Jiang, W.; Han, W.; Wang, Y.; Tang, X.; Li, L.; et al. Glutamylation of an HIV-1 protein inhibits the immune response by hijacking STING. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Xu, X.; Ma, C.; Zhang, P.; Ji, W.; Liu, X. HIV-1 p17 matrix protein enhances type I interferon responses through the p17-OLA1-STING axis. J. Cell Sci. 2024, 137, jcs261500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, D.E.; Ganser-Pornillos, B.K.; Johnson, J.S.; Pornillos, O.; Sundquist, W.I. Reconstitution and visualization of HIV-1 capsid-dependent replication and integration in vitro. Science 2020, 370, eabc8420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, T.M.; Arnold, L.M.; Powers, J.A.; McCann, D.A.; Rowe, A.B.; Christensen, D.E.; Pereira, M.J.; Zhou, W.; Torrez, R.M.; Iwasa, J.H.; et al. Cell-free assays reveal that the HIV-1 capsid protects reverse transcripts from cGAS immune sensing. PLoS Pathog. 2025, 21, e1012206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Gayo, E.; Gao, C.; Calvet-Mirabent, M.; Ouyang, Z.; Lichterfeld, M.; Yu, X.G. Cooperation between cGAS and RIG-I sensing pathways enables improved innate recognition of HIV-1 by myeloid dendritic cells in elite controllers. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1017164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Su, J.; Chen, R.; Wei, W.; Yuan, Z.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Liang, H.; Ye, L.; Jiang, J. The Role of Innate Immunity in Natural Elite Controllers of HIV-1 Infection. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 780922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sowd, G.A.; Shi, J.; Aiken, C. HIV-1 CA Inhibitors Are Antagonized by Inositol Phosphate Stabilization of the Viral Capsid in Cells. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e01445-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bester, S.M.; Wei, G.; Zhao, H.; Adu-Ampratwum, D.; Iqbal, N.; Courouble, V.V.; Francis, A.C.; Annamalai, A.S.; Singh, P.K.; Shkriabai, N.; et al. Structural and mechanistic bases for a potent HIV-1 capsid inhibitor. Science 2020, 370, 360–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bester, S.M.; Adu-Ampratwum, D.; Annamalai, A.S.; Wei, G.; Briganti, L.; Murphy, B.C.; Haney, R.; Fuchs, J.R.; Kvaratskhelia, M. Structural and Mechanistic Bases of Viral Resistance to HIV-1 Capsid Inhibitor Lenacapavir. mBio 2022, 13, e01804-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Protein | Type | Effect on cGAS-STING | Mechanism | References |

| TREX1 | HIV-specific | Negative | Degrades cytoplasmic HIV-1 cDNA | [13,45,46,47] |

| SAMHD1 | HIV-specific | Negative | Depletes cellular nucleotide pools and, consequently, restricts HIV-1 reverse transcription | [48,49,50,51,52] |

| PBQP1 | HIV-specific | Positive | Interacts with the HIV-1 capsid in the cytoplasm and stimulates cGAS recruitment onto viral cDNA | [53,54,55,56] |

| NONO | HIV-specific | Positive | Interacts with the HIV-1 capsid in the nucleus and stimulates cGAS recruitment onto viral cDNA | [27] |

| IFI16 | Universal | Positive | Binds to HIV-1 cDNA in the cytoplasm and, subsequently, promotes the STING-TBK1 interaction | [13,61,62,63] |

| ISG15 | Universal | Positive | Promotes the ISGylation of STING, facilitating STING oligomerization | [64] |

| NLRX1 | Universal | Negative | Disrupts the STING-TBK1 association | [67] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mashkovskaia, A.; Agapkina, Y.; Oretskaya, T.; Gottikh, M.; Anisenko, A. HIV-1 and Its Strategy for Hiding Viral cDNA from STING-Mediated Innate Immunity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11635. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311635

Mashkovskaia A, Agapkina Y, Oretskaya T, Gottikh M, Anisenko A. HIV-1 and Its Strategy for Hiding Viral cDNA from STING-Mediated Innate Immunity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11635. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311635

Chicago/Turabian StyleMashkovskaia, Anna, Yulia Agapkina, Tatiana Oretskaya, Marina Gottikh, and Andrey Anisenko. 2025. "HIV-1 and Its Strategy for Hiding Viral cDNA from STING-Mediated Innate Immunity" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11635. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311635

APA StyleMashkovskaia, A., Agapkina, Y., Oretskaya, T., Gottikh, M., & Anisenko, A. (2025). HIV-1 and Its Strategy for Hiding Viral cDNA from STING-Mediated Innate Immunity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11635. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311635