Intratumoral Microbiota Correlates with AP-2 Expression: A Pan-Cancer Map with Cohort-Specific Prognostic and Molecular Footprints

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Despite Each Tumor Type Having Its Own Bacterial Composition, Some Commonalities Were Noted

2.2. Correlation of Microbiota Abundance and AP-2 Expression Revealed That More than Half of the Cohorts Contain Significant Relationships, with Some of Them Having Prognostic Importance

2.3. Species-Level Correlation Analysis and Assessment of Prognostic Significance Have Enabled the Selection of Promising Relationships in Four Cohorts

2.4. Establishment of Representative Patient Groups Reaffirmed Survival Outcomes and Revealed Distinct Clinical Features

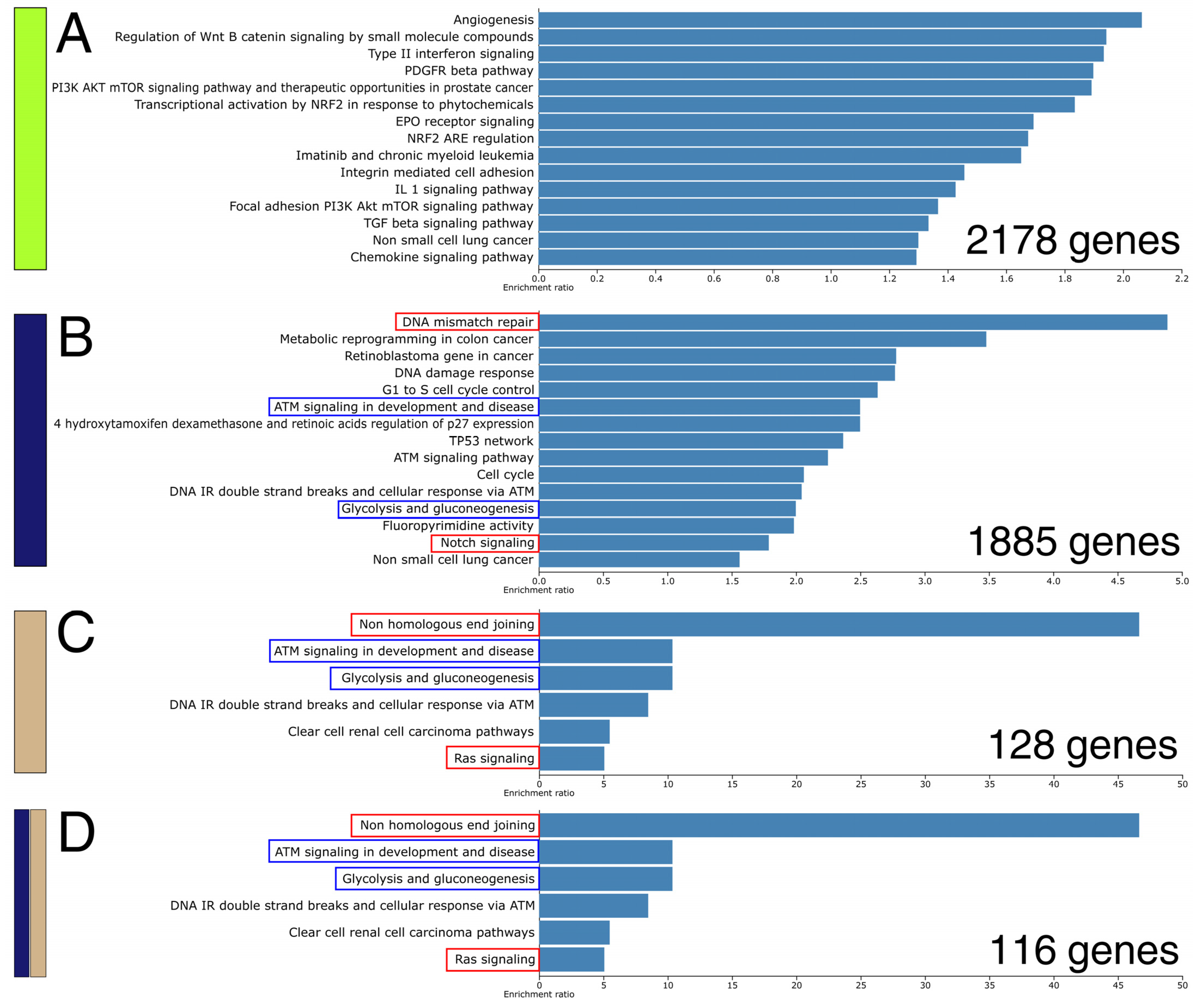

2.5. An Attempt to Identify a Consensus Expression Profile Dependent on AP-2 and Microbiota Uncovered Genes Regulating Various Biological Processes and Pathways

2.6. AP-2 Engagement of Microbiota-Responsive Chromatin in ACC and DLBC Contrasts with a Null Pattern in STAD

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Assessment of Bacterial Composition and Diversity in a Pan-Cancer View

4.2. Acquisition and Processing of Gene Expression and Microbiota Abundance Data

4.3. Correlation Analysis

4.4. Survival Analysis

4.5. Intersection Analysis Followed by Assessment of Prognostic Outcomes

4.6. Investigating Clinical Profile and Performing Differential Expression Analysis (DEA) Among Representative Groups of Patients

4.7. Bootstrapping and Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis (WGCNA)

4.8. Overlapping DEA and WGCNA Data Alongside Gene Ontology

4.9. Proximity Analysis Around Microbiota-Responsive Genes and FG/BG Set Construction

4.10. AP-2 Motif Scanning, ChIP-Seq Integration, and Enrichment Testing

4.11. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Establishment of Microbiota-Responsive Gene Sets

Appendix A.2. Acquisition of Genes Related to AP-2β and AP-2ε

References

- Chen, B.Y.; Lin, W.Z.; Li, Y.L.; Bi, C.; Du, L.J.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, L.J.; Liu, T.; Xu, S.; Shi, C.J.; et al. Roles of oral microbiota and oral-gut microbial transmission in hypertension. J. Adv. Res. 2023, 43, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adu-Oppong, B.; Thanert, R.; Wallace, M.A.; Burnham, C.D.; Dantas, G. Substantial overlap between symptomatic and asymptomatic genitourinary microbiota states. Microbiome 2022, 10, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, D.; Jin, C.; Yue, K.; Yue, M.; Liang, Y.; Xue, X.; Li, P.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, L. Pan-cancer atlas of tumor-resident microbiome, immunity and prognosis. Cancer Lett. 2024, 598, 217077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.M.; Fidelle, M.; Routy, B.; Kroemer, G.; Wargo, J.A.; Segata, N.; Zitvogel, L. Gut OncoMicrobiome Signatures (GOMS) as next-generation biomarkers for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 20, 583–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overacre-Delgoffe, A.E.; Bumgarner, H.J.; Cillo, A.R.; Burr, A.H.P.; Tometich, J.T.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Bruno, T.C.; Vignali, D.A.A.; Hand, T.W. Microbiota-specific T follicular helper cells drive tertiary lymphoid structures and anti-tumor immunity against colorectal cancer. Immunity 2021, 54, 2812–2824.e2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pevsner-Fischer, M.; Tuganbaev, T.; Meijer, M.; Zhang, S.H.; Zeng, Z.R.; Chen, M.H.; Elinav, E. Role of the microbiome in non-gastrointestinal cancers. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 7, 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeano Nino, J.L.; Wu, H.; LaCourse, K.D.; Kempchinsky, A.G.; Baryiames, A.; Barber, B.; Futran, N.; Houlton, J.; Sather, C.; Sicinska, E.; et al. Effect of the intratumoral microbiota on spatial and cellular heterogeneity in cancer. Nature 2022, 611, 810–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heymann, C.J.F.; Bard, J.M.; Heymann, M.F.; Heymann, D.; Bobin-Dubigeon, C. The intratumoral microbiome: Characterization methods and functional impact. Cancer Lett. 2021, 522, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, Y.; Baines, K.J.; Maleki Vareki, S. Microbiome bacterial influencers of host immunity and response to immunotherapy. Cell Rep. Med. 2024, 5, 101487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panebianco, C.; Andriulli, A.; Pazienza, V. Pharmacomicrobiomics: Exploiting the drug-microbiota interactions in anticancer therapies. Microbiome 2018, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.Y.; Mei, J.X.; Yu, G.; Lei, L.; Zhang, W.H.; Liu, K.; Chen, X.L.; Kolat, D.; Yang, K.; Hu, J.K. Role of the gut microbiota in anticancer therapy: From molecular mechanisms to clinical applications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Said, S.S.; Ibrahim, W.N. Gut Microbiota-Tumor Microenvironment Interactions: Mechanisms and Clinical Implications for Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Efficacy in Cancer. Cancer Manag. Res. 2025, 17, 171–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Li, J.; Cai, W.; Huang, Y.; Liu, X.; Ma, Z.; Tang, Z.; Bian, X.; Zheng, J.; Jiang, J.; et al. The emerging tumor microbe microenvironment: From delineation to multidisciplinary approach-based interventions. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2024, 14, 1560–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujisaka, S.; Watanabe, Y.; Tobe, K. The gut microbiome: A core regulator of metabolism. J. Endocrinol. 2023, 256, e220111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambring, C.B.; Siraj, S.; Patel, K.; Sankpal, U.T.; Mathew, S.; Basha, R. Impact of the Microbiome on the Immune System. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 39, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Wan, S.; Hu, P.; Li, Y.; Li, S. Editorial: Transcriptional Regulation in Metabolism and Immunology. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 845697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, R.G.; Davenport, E.R. The relationship between the gut microbiome and host gene expression: A review. Hum. Genet. 2021, 140, 747–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camp, J.G.; Frank, C.L.; Lickwar, C.R.; Guturu, H.; Rube, T.; Wenger, A.M.; Chen, J.; Bejerano, G.; Crawford, G.E.; Rawls, J.F. Microbiota modulate transcription in the intestinal epithelium without remodeling the accessible chromatin landscape. Genome Res. 2014, 24, 1504–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, J.M.; Lickwar, C.R.; Song, L.; Breton, G.; Crawford, G.E.; Rawls, J.F. Microbiota regulate intestinal epithelial gene expression by suppressing the transcription factor Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha. Genome Res. 2017, 27, 1195–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meisel, J.S.; Sfyroera, G.; Bartow-McKenney, C.; Gimblet, C.; Bugayev, J.; Horwinski, J.; Kim, B.; Brestoff, J.R.; Tyldsley, A.S.; Zheng, Q.; et al. Commensal microbiota modulate gene expression in the skin. Microbiome 2018, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmierczak-Siedlecka, K.; Ruszkowski, J.; Skonieczna-Zydecka, K.; Jedrzejczak, J.; Folwarski, M.; Makarewicz, W. Gastrointestinal cancers: The role of microbiota in carcinogenesis and the role of probiotics and microbiota in anti-cancer therapy efficacy. Cent. Eur. J. Immunol. 2020, 45, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingender, E.; Schoeps, T.; Haubrock, M.; Krull, M.; Donitz, J. TFClass: Expanding the classification of human transcription factors to their mammalian orthologs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D343–D347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Luo, Y.; Liang, Z.; Li, X.; Kolat, D.; Zhao, L.; Xiong, W. Crucial role of the transcription factors family activator protein 2 in cancer: Current clue and views. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.J.; Kolat, D.; Kaluzinska-Kolat, Z.; Liang, Z.; Peng, B.Q.; Zhu, Y.F.; Liu, K.; Mei, J.X.; Yu, G.; Zhang, W.H.; et al. The AP-2 Family of Transcription Factors-Still Undervalued Regulators in Gastroenterological Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, D.; Buhl, S.; Weber, S.; Jager, R.; Schorle, H. The AP-2 family of transcription factors. Genome Biol. 2005, 6, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.R.; Zhang, J. AP-2α expression in papillary thyroid carcinoma predicts tumor progression and poor prognosis. Cancer Manag. Res. 2018, 10, 2615–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolat, D.; Kaluzinska, Z.; Bednarek, A.K.; Pluciennik, E. The biological characteristics of transcription factors AP-2α and AP-2γ and their importance in various types of cancers. Biosci. Rep. 2019, 39, BSR20181928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Q.; Shi, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, S.; Liu, Z.; Sun, X.; Di, X. Identification and verification of aging-related lncRNAs for prognosis prediction and immune microenvironment in patients with head and neck squamous carcinoma. Oncol. Res. 2023, 31, 35–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, L.; Wang, Y.; Kannan, P.; Tainsky, M.A. Functional characterization of the interacting domains of the positive coactivator PC4 with the transcription factor AP-2α. Gene 2003, 320, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Satoda, M.; Licht, J.D.; Hayashizaki, Y.; Gelb, B.D. Cloning and characterization of a novel mouse AP-2 transcription factor, AP-2δ, with unique DNA binding and transactivation properties. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 40755–40760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolat, D.; Kaluzinska, Z.; Orzechowska, M.; Bednarek, A.K.; Pluciennik, E. Functional genomics of AP-2α and AP-2γ in cancers: In silico study. BMC Med. Genom. 2020, 13, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, C.; Wen, H.; Wang, S.; Shu, G.; Wang, M.; Yi, H.; Guo, K.; Pan, Q.; Yin, G. Potential prognosis and immunotherapy predictor TFAP2A in pan-cancer. Aging 2024, 16, 1021–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Jia, L.; Cui, S.; Shi, Y.; Chang, A.; Zeng, X.; Wang, P. AP-2α suppresses invasion in BeWo cells by repression of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 and up-regulation of E-cadherin. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2013, 381, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xiong, W.; Liang, Z.; Wang, J.; Zeng, Z.; Kolat, D.; Li, X.; Zhou, D.; Xu, X.; Zhao, L. Critical role of the gut microbiota in immune responses and cancer immunotherapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 17, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolat, D.; Zhao, L.Y.; Kciuk, M.; Pluciennik, E.; Kaluzinska-Kolat, Z. AP-2δ Is the Most Relevant Target of AP-2 Family-Focused Cancer Therapy and Affects Genome Organization. Cells 2022, 11, 4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolat, D.; Kaluzinska, Z.; Bednarek, A.K.; Pluciennik, E. Prognostic significance of AP-2α/γ targets as cancer therapeutics. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Jia, W.; Bai, L.; Lin, Q. Dysregulation of lncRNA TFAP2A-AS1 is involved in the pathogenesis of pulpitis by the regulation of microRNA-32-5p. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2024, 12, e1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Chen, W.D.; Wang, Y.D. The roles of the gut microbiota-miRNA interaction in the host pathophysiology. Mol. Med. 2020, 26, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prukpitikul, P.; Sirivarasai, J.; Sutjarit, N. The molecular mechanisms underlying gut microbiota-miRNA interaction in metabolic disorders. Benef. Microbes. 2024, 15, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraune, C.; Harms, L.; Buscheck, F.; Hoflmayer, D.; Tsourlakis, M.C.; Clauditz, T.S.; Simon, R.; Moller, K.; Luebke, A.M.; Moller-Koop, C.; et al. Upregulation of the transcription factor TFAP2D is associated with aggressive tumor phenotype in prostate cancer lacking the TMPRSS2:ERG fusion. Mol. Med. 2020, 26, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frierson, H.F., Jr.; El-Naggar, A.K.; Welsh, J.B.; Sapinoso, L.M.; Su, A.I.; Cheng, J.; Saku, T.; Moskaluk, C.A.; Hampton, G.M. Large scale molecular analysis identifies genes with altered expression in salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma. Am. J. Pathol. 2002, 161, 1315–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assie, G.; Letouze, E.; Fassnacht, M.; Jouinot, A.; Luscap, W.; Barreau, O.; Omeiri, H.; Rodriguez, S.; Perlemoine, K.; Rene-Corail, F.; et al. Integrated genomic characterization of adrenocortical carcinoma. Nat. Genet. 2014, 46, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Shi, J.; Wu, X.; Yan, S.; Gao, Z.; Liu, Y. Gut microbiota is associated with the disease characteristics of patients with newly diagnosed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2025, 15, 2285–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.E.; Kang, W.; Choi, S.; Park, Y.; Chalita, M.; Kim, H.; Lee, J.H.; Hyun, D.W.; Ryu, K.J.; Sung, H.; et al. The influence of microbial dysbiosis on immunochemotherapy-related efficacy and safety in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood 2023, 141, 2224–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Mao, D.; Jin, C.; Wang, J.; Lai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Ge, Q.; Zhang, P.; Sun, Y.; et al. The gut microbiota correlate with the disease characteristics and immune status of patients with untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1105293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Shi, C.; Qian, J.; Yu, X.; Wang, S.; Shao, L.; Yu, W. The gut microbiota is altered significantly in primary diffuse large b-cell lymphoma patients and relapse refractory diffuse large b-cell lymphoma patients. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2025, 27, 2347–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yijia, Z.; Li, X.; Ma, L.; Wang, S.; Du, H.; Wu, Y.; Yu, J.; Xiang, Y.; Xiong, D.; Shan, H.; et al. Identification of intratumoral microbiome-driven immune modulation and therapeutic implications in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2025, 74, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.E.; Kang, W.; Chalita, M.; Lim, J.; Kim, W.S.; Kim, S.J. Comprehensive Understanding of Gut Microbiota in Treatment Naïve Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma Patients. Blood 2021, 138, 2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Han, S.; Xiao, X.; Zheng, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, X.; Zhou, S.; Yu, K.; Huang, L.; et al. Integration analysis of tumor metagenome and peripheral immunity data of diffuse large-B cell lymphoma. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1146861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Xiong, S.; Xiong, J.; Deng, X.; Long, Q.; Li, Y. Integrated analysis of the microbiome and transcriptome in stomach adenocarcinoma. Open Life Sci. 2023, 18, 20220528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, R.M.; Menor, M.; Hernandez, B.Y.; Deng, Y.; Khadka, V.S. Bacterial Diversity Correlates with Overall Survival in Cancers of the Head and Neck, Liver, and Stomach. Molecules 2021, 26, 5659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Hui, C. PLVAP protein expression correlated with microbial composition, clinicopathological features, and prognosis of patients with stomach adenocarcinoma. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 149, 7139–7153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.L.; Pang, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.J. The Gastric Microbiome Is Perturbed in Advanced Gastric Adenocarcinoma Identified Through Shotgun Metagenomics. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Lv, L.; Pan, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.J.; Chen, J.G.; Chen, Y.B.; Li, Y.Q.; Wang, Q.J.; He, J.; et al. Reduced expression of transcription factor AP-2α is associated with gastric adenocarcinoma prognosis. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Feng, L.; Wang, H.; Zhou, H.; Li, Q.; Zhang, W.; Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Luan, X.; Jiang, Z.; et al. Association Between Oral Microbiota and Human Brain Glioma Grade: A Case-Control Study. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 746568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvevi, A.; Laffusa, A.; Gallo, C.; Invernizzi, P.; Massironi, S. Any Role for Microbiota in Cholangiocarcinoma? A Comprehensive Review. Cells 2023, 12, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Du, Y.; He, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, J.; Jia, B.; Chen, J.; Peng, X.; An, T.; Li, J.; et al. Lactate production by tumor-resident Staphylococcus promotes metastatic colonization in lung adenocarcinoma. Cell Host Microbe 2025, 33, 1089–1105.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Li, J.; Zhou, X. Lung microbiome: New insights into the pathogenesis of respiratory diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Sandhu, E.; Yang, X.; Yang, J.; Ren, Y.; Gao, X. Bidirectional Functional Effects of Staphylococcus on Carcinogenesis. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szmajda-Krygier, D.; Krygier, A.; Zebrowska-Nawrocka, M.; Pietrzak, J.; Swiechowski, R.; Wosiak, A.; Jelen, A.; Balcerczak, E. Differential Expression of AP-2 Transcription Factors Family in Lung Adenocarcinoma and Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma—A Bioinformatics Study. Cells 2023, 12, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.C.; Grencewicz, D.; Chakravarthy, K.; Li, L.; Liepold, R.; Wolf, M.; Sangwan, N.; Tzeng, A.; Hoyd, R.; Jhawar, S.R.; et al. Breast tumor microbiome regulates anti-tumor immunity and T cell-associated metabolites. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, J.; Xia, L.; Xia, Q. Macroscopic inhibition of DNA damage repair pathways by targeting AP-2α with LEI110 eradicates hepatocellular carcinoma. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, H.; Kim, D.; Kang, J.; Son, B.; Seo, D.; Youn, H.; Youn, B.; Kim, W. TFAP2C increases cell proliferation by downregulating GADD45B and PMAIP1 in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Biol. Res. 2019, 52, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Xia, H.; Tan, X.; Shi, C.; Ma, Y.; Meng, D.; Zhou, M.; Lv, Z.; Wang, S.; Jin, Y. Intratumoural microbiota: A new frontier in cancer development and therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, A.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Intratumoral microbiota: Roles in cancer initiation, development and therapeutic efficacy. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2023, 8, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wang, M.; Jiang, H.; Feng, C.; Li, Y.X. Intratumoral microbiota is associated with prognosis in patients with adrenocortical carcinoma. iMeta 2023, 2, e102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network; Weinstein, J.N.; Collisson, E.A.; Mills, G.B.; Shaw, K.R.; Ozenberger, B.A.; Ellrott, K.; Shmulevich, I.; Sander, C.; Stuart, J.M. The Cancer Genome Atlas Pan-Cancer analysis project. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.P.; Hsu, C.L.; Oyang, Y.J.; Huang, H.C.; Juan, H.F. BIC: A database for the transcriptional landscape of bacteria in cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D1205–D1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, M.A.; Ferretti, V.; Grossman, R.L.; Staudt, L.M. The NCI Genomic Data Commons as an engine for precision medicine. Blood 2017, 130, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lichtenberg, T.; Hoadley, K.A.; Poisson, L.M.; Lazar, A.J.; Cherniack, A.D.; Kovatich, A.J.; Benz, C.C.; Levine, D.A.; Lee, A.V.; et al. An Integrated TCGA Pan-Cancer Clinical Data Resource to Drive High-Quality Survival Outcome Analytics. Cell 2018, 173, 400–416.e411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogluszka, M.; Orzechowska, M.; Jedroszka, D.; Witas, P.; Bednarek, A.K. Evaluate Cutpoints: Adaptable continuous data distribution system for determining survival in Kaplan-Meier estimator. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2019, 177, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, M.E.; Phipson, B.; Wu, D.; Hu, Y.; Law, C.W.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, C.W.; Chen, Y.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. voom: Precision weights unlock linear model analysis tools for RNA-seq read counts. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, R29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Seesi, S.; Tiagueu, Y.T.; Zelikovsky, A.; Mandoiu, I.I. Bootstrap-based differential gene expression analysis for RNA-Seq data with and without replicates. BMC Genom. 2014, 15 (Suppl. 8), S2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulesa, A.; Krzywinski, M.; Blainey, P.; Altman, N. Sampling distributions and the bootstrap. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 477–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Wu, S.; Gao, J.; Qin, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, J. Weighted gene co expression network analysis (WGCNA) with key pathways and hub-genes related to micro RNAs in ischemic stroke. IET Syst. Biol. 2021, 15, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Silva, F.; Venancio, T.M. BioNERO: An all-in-one R/Bioconductor package for comprehensive and easy biological network reconstruction. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2022, 22, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corces, M.R.; Granja, J.M.; Shams, S.; Louie, B.H.; Seoane, J.A.; Zhou, W.; Silva, T.C.; Groeneveld, C.; Wong, C.K.; Cho, S.W.; et al. The chromatin accessibility landscape of primary human cancers. Science 2018, 362, eaav1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consortium, E.P. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature 2012, 489, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, G.; Barber, G.P.; Benet-Pages, A.; Casper, J.; Clawson, H.; Diekhans, M.; Fischer, C.; Gonzalez, J.N.; Hinrichs, A.S.; Lee, C.M.; et al. The UCSC Genome Browser database: 2025 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D1243–D1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Kinne, J.; Ding, L.; Rath, E.C.; Cox, A.; Naidu, S.D. Identification of genome-wide non-canonical spliced regions and analysis of biological functions for spliced sequences using Read-Split-Fly. BMC Bioinform. 2017, 18, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, A.R. BEDTools: The Swiss-Army Tool for Genome Feature Analysis. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2014, 47, 11.12.11–11.12.34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilbrun, E.E.; Tseitline, D.; Wasserman, H.; Kirshenbaum, A.; Cohen, Y.; Gordan, R.; Adar, S. The epigenetic landscape shapes smoking-induced mutagenesis by modulating DNA damage susceptibility and repair efficiency. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, gkaf048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capriotti, E.; Fariselli, P. PhD-SNPg: Updating a webserver and lightweight tool for scoring nucleotide variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W451–W458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorontsov, I.E.; Eliseeva, I.A.; Zinkevich, A.; Nikonov, M.; Abramov, S.; Boytsov, A.; Kamenets, V.; Kasianova, A.; Kolmykov, S.; Yevshin, I.S.; et al. HOCOMOCO in 2024: A rebuild of the curated collection of binding models for human and mouse transcription factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D154–D163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, C.E.; Bailey, T.L.; Noble, W.S. FIMO: Scanning for occurrences of a given motif. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 1017–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taing, L.; Dandawate, A.; L’Yi, S.; Gehlenborg, N.; Brown, M.; Meyer, C.A. Cistrome Data Browser: Integrated search, analysis and visualization of chromatin data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D61–D66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, K.J.; Yoon, Y.A.; Park, J.H. Evaluation of Liftover Tools for the Conversion of Genome Reference Consortium Human Build 37 to Build 38 Using ClinVar Variants. Genes 2023, 14, 1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layer, R.M.; Skadron, K.; Robins, G.; Hall, I.M.; Quinlan, A.R. Binary Interval Search: A scalable algorithm for counting interval intersections. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid-Burgk, J.L.; Gao, L.; Li, D.; Gardner, Z.; Strecker, J.; Lash, B.; Zhang, F. Highly Parallel Profiling of Cas9 Variant Specificity. Mol. Cell 2020, 78, 794–800.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, F.M.; Wang, C.R.; Chen, P.Y. Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing in Maize. Bio-Protocol 2018, 8, e2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, X.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Gao, C.; Li, S.; Wei, C.; Huang, J.; Tian, Y.; Yuan, J.; Lu, J.; et al. Intratumor microbiome features reveal antitumor potentials of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2156255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wu, W.; Gong, D.; Shang, R.; Wang, J.; Yu, H. Propionibacterium acnes overabundance in gastric cancer promote M2 polarization of macrophages via a TLR4/PI3K/Akt signaling. Gastric Cancer 2021, 24, 1242–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.H.; Hong, C.; Lee, A.R.; Sung, J.; Hwang, T.H. Multi-omics reveals microbiome, host gene expression, and immune landscape in gastric carcinogenesis. iScience 2022, 25, 103956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groen, R.A.L.; Schrader, A.M.R.; Kersten, M.J.; Pals, S.T.; Vermaat, J.S.P. MYD88 in the driver’s seat of B-cell lymphomagenesis: From molecular mechanisms to clinical implications. Haematologica 2019, 104, 2337–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaza-Correa, J.M.; Liang, Z.; van den Berg, A.; Diepstra, A.; Visser, L. Toll-like receptors in the pathogenesis of human B cell malignancies. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2014, 7, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Bailey, A.; Kuleshov, M.V.; Clarke, D.J.B.; Evangelista, J.E.; Jenkins, S.L.; Lachmann, A.; Wojciechowicz, M.L.; Kropiwnicki, E.; Jagodnik, K.M.; et al. Gene Set Knowledge Discovery with Enrichr. Curr. Protoc. 2021, 1, e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Aksoy, B.A.; Dogrusoz, U.; Dresdner, G.; Gross, B.; Sumer, S.O.; Sun, Y.; Jacobsen, A.; Sinha, R.; Larsson, E.; et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci. Signal 2013, 6, pl1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, H.E.; Bishop, A.J.R. Correlation AnalyzeR: Functional predictions from gene co-expression correlations. BMC Bioinform. 2021, 22, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrashekar, D.S.; Karthikeyan, S.K.; Korla, P.K.; Patel, H.; Shovon, A.R.; Athar, M.; Netto, G.J.; Qin, Z.S.; Kumar, S.; Manne, U.; et al. UALCAN: An update to the integrated cancer data analysis platform. Neoplasia 2022, 25, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liska, O.; Bohar, B.; Hidas, A.; Korcsmaros, T.; Papp, B.; Fazekas, D.; Ari, E. TFLink: An integrated gateway to access transcription factor-target gene interactions for multiple species. Database 2022, 2022, baac083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stelzer, G.; Rosen, N.; Plaschkes, I.; Zimmerman, S.; Twik, M.; Fishilevich, S.; Stein, T.I.; Nudel, R.; Lieder, I.; Mazor, Y.; et al. The GeneCards Suite: From Gene Data Mining to Disease Genome Sequence Analyses. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2016, 54, 1.30.1–1.30.33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamant, I.; Clarke, D.J.B.; Evangelista, J.E.; Lingam, N.; Ma’ayan, A. Harmonizome 3.0: Integrated knowledge about genes and proteins from diverse multi-omics resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D1016–D1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plaisier, C.L.; O’Brien, S.; Bernard, B.; Reynolds, S.; Simon, Z.; Toledo, C.M.; Ding, Y.; Reiss, D.J.; Paddison, P.J.; Baliga, N.S. Causal Mechanistic Regulatory Network for Glioblastoma Deciphered Using Systems Genetics Network Analysis. Cell Syst. 2016, 3, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhou, L.; Qian, F.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Song, C.; et al. TFTG: A comprehensive database for human transcription factors and their targets. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 23, 1877–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| TCGA Tumor Cohort | Microbiota (Genus-Level) | AP-2 TF | Correlation Coefficient and Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACC | Paraburkholderia | TFAP2E | r = 0.55; p < 0.0001 (****) |

| CESC | Meiothermus | TFAP2B | r = 0.36; p < 0.0001 (****) |

| CHOL | Halomonas | TFAP2B | r = 0.41; p < 0.05 (*) |

| Liberibacter | r = 0.45; p < 0.01 (**) | ||

| Moraxella | TFAP2A-AS1 | r = 0.38; p < 0.05 (*) | |

| Sphingomonas | r = 0.35; p < 0.05 (*) | ||

| COAD | Brucella | TFAP2E | r = 0.38; p < 0.0001 (****) |

| DLBC | Actinomyces | TFAP2E | r = 0.65; p < 0.0001 (****) |

| TFAP2E-AS1 | r = 0.67; p < 0.0001 (****) | ||

| Alcaligenes | TFAP2A-AS2 | r = 0.49; p < 0.001 (***) | |

| Brucella | TFAP2A-AS2 | r = 0.31; p < 0.05 (*) | |

| Corynebacterium | TFAP2E-AS1 | r = 0.33; p < 0.05 (*) | |

| Cutibacterium | TFAP2A-AS2 | r = 0.32; p < 0.05 (*) | |

| Gordonia | TFAP2E | r = 0.39; p < 0.01 (**) | |

| TFAP2E-AS1 | r = 0.41; p < 0.01 (**) | ||

| TFAP2A-AS1 | r = 0.31; p < 0.05 (*) | ||

| TFAP2A-AS2 | r = 0.37; p < 0.05 (*) | ||

| Halomonas | TFAP2E-AS1 | r = 0.47; p < 0.001 (***) | |

| Meiothermus | TFAP2E | r = 0.32; p < 0.05 (*) | |

| TFAP2A-AS1 | r = 0.38; p < 0.01 (**) | ||

| TFAP2A-AS2 | r = 0.51; p < 0.001 (***) | ||

| Paraburkholderia | TFAP2E-AS1 | r = 0.36; p < 0.05 (*) | |

| TFAP2A-AS2 | r = 0.51; p < 0.001 (***) | ||

| Sphingomonas | TFAP2A | r = 0.47; p < 0.001 (***) | |

| ESCA | Shewanella | TFAP2E-AS1 | r = 0.38; p < 0.0001 (****) |

| GBM | Clostridium | TFAP2D | r = 0.79; p < 0.0001 (****) |

| Haemophilus | TFAP2C | r = 0.39; p < 0.0001 (****) | |

| Halomonas | TFAP2D | r = 0.48; p < 0.0001 (****) | |

| Klebsiella | TFAP2D | r = 0.57; p < 0.0001 (****) | |

| KICH | Corynebacterium | TFAP2B | r = 0.97; p < 0.0001 (****) |

| Halomonas | TFAP2E | r = 0.43; p < 0.001 (***) | |

| TFAP2A-AS2 | r = 0.50; p < 0.0001 (****) | ||

| Vibrio | TFAP2E | r = 0.32; p < 0.01 (**) | |

| TFAP2A-AS1 | r = 0.72; p < 0.0001 (****) | ||

| TFAP2A-AS2 | r = 0.47; p < 0.0001 (****) | ||

| LAML | Aquitalea | TFAP2E-AS1 | r = 0.36; p < 0.0001 (****) |

| Porphyrobacter | TFAP2D | r = 0.30; p < 0.001 (***) | |

| Thiopseudomonas | TFAP2D | r = 0.33; p < 0.0001 (****) | |

| LIHC | Halomonas | TFAP2D | r = 0.42; p < 0.0001 (****) |

| MESO | Meiothermus | TFAP2D | r = 0.35; p < 0.01 (**) |

| TFAP2E-AS1 | r = 0.31; p < 0.01 (**) | ||

| PCPG | Escherichia | TFAP2D | r = 0.34; p < 0.0001 (****) |

| Gordonia | TFAP2A-AS1 | r = 0.35; p < 0.0001 (****) | |

| Mitsuaria | TFAP2E-AS1 | r = 0.33; p < 0.0001 (****) | |

| READ | Aquirufa | TFAP2E | r = 0.35; p < 0.0001 (****) |

| Moraxella | TFAP2A-AS1 | r = 0.32; p < 0.0001 (****) | |

| Limnohabitans | TFAP2E-AS1 | r = 0.34; p < 0.0001 (****) | |

| Polynucleobacter | TFAP2E-AS1 | r = 0.30; p < 0.0001 (****) | |

| SARC | Halomonas | TFAP2D | r = 0.37; p < 0.0001 (****) |

| Staphylococcus | TFAP2B | r = 0.38; p < 0.0001 (****) | |

| SKCM | Halomonas | TFAP2E-AS1 | r = 0.31; p < 0.01 (**) |

| STAD | Cutibacterium | TFAP2B | r = 0.51; p < 0.0001 (****) |

| UCS | Corynebacterium | TFAP2B | r = 0.85; p < 0.0001 (****) |

| Priestia | TFAP2A | r = 0.38; p < 0.01 (**) | |

| Solimonas | TFAP2E-AS1 | r = 0.32; p < 0.05 (*) | |

| UVM | Staphylococcus | TFAP2E-AS1 | r = 0.50; p < 0.0001 (****) |

| TCGA Tumor Cohort | Microbiota (Species-Level) | AP-2 TF | Correlation Coefficient and Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACC | Paraburkholderia fungorum | TFAP2E | r = 0.50; p < 0.0001 (****) |

| COAD | Brucella anthropi | TFAP2E | r = 0.20; p < 0.0001 (****) |

| DLBC | Actinomyces oris | TFAP2E | r = 0.47; p < 0.001 (***) |

| TFAP2E-AS1 | r = 0.46; p < 0.01 (**) | ||

| Halomonas sp. JS92-SW72 | TFAP2E-AS1 | r = 0.29; p < 0.05 (*) | |

| GBM | Clostridium botulinum | TFAP2D | r = 0.32; p < 0.0001 (****) |

| Haemophilus parainfluenzae | TFAP2C | r = 0.18; p < 0.05 (*) | |

| KICH | Halomonas sp. JS92-SW72 | TFAP2A-AS2 | r = 0.35; p < 0.01 (**) |

| Vibrio anguillarum | TFAP2A-AS1 | r = 0.48; p < 0.0001 (****) | |

| TFAP2A-AS2 | r = 0.39; p < 0.01 (**) | ||

| LIHC | Halomonas sp. JS92-SW72 | TFAP2D | r = 0.18; p < 0.001 (***) |

| PCPG | Mitsuaria sp. 7 | TFAP2E-AS1 | r = 0.38; p < 0.0001 (****) |

| READ | Limnohabitans sp. 103DPR2 | TFAP2E-AS1 | r = 0.37; p < 0.0001 (****) |

| Limnohabitans sp. 63ED37-2 | r = 0.35; p < 0.0001 (****) | ||

| Polynucleobacter sp. Adler-ghost | r = 0.22; p < 0.01 (**) | ||

| SARC | Halomonas sp. JS92-SW72 | TFAP2D | r = 0.25; p < 0.0001 (****) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | TFAP2B | r = 0.33; p < 0.0001 (****) | |

| STAD | Cutibacterium acnes | TFAP2B | r = 0.44; p < 0.0001 (****) |

| Cutibacterium granulosum | r = 0.37; p < 0.0001 (****) | ||

| Cutibacterium modestum | r = 0.63; p < 0.0001 (****) | ||

| UCS | Solimonas sp. K1W22B-7 | TFAP2E-AS1 | r = 0.34; p < 0.05 (*) |

| UVM | Staphylococcus aureus | TFAP2E-AS1 | r = 0.38; p < 0.001 (***) |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | r = 0.72; p < 0.0001 (****) |

| Cohort | Radius (kb) | Odds Ratio | Fisher p-Value | Empirical p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACC | 250 | 1.138 | 8.915 × 10−2 | 8.139 × 10−2 |

| 500 | 1.156 | 2.079 × 10−2 | 2.37 × 10−2 | |

| 750 | 1.281 | 2.403 × 10−5 | 1.00 × 10−4 | |

| 1000 | 1.219 | 1.227 × 10−4 | 2.00 × 10−4 | |

| DLBC | 250 | 1.241 | 3.496 × 10−3 | 2.90 × 10−3 |

| 500 | 1.167 | 4.839 × 10−3 | 4.40 × 10−3 | |

| 750 | 1.258 | 7.099 × 10−6 | 1.00 × 10−4 | |

| 1000 | 1.106 | 1.643 × 10−2 | 1.58 × 10−2 | |

| STAD | 250 | 0.835 | 8.373 × 10−1 | 2.167 × 10−1 |

| 500 | 0.831 | 9.068 × 10−1 | 1.195 × 10−1 | |

| 750 | 0.827 | 9.524 × 10−1 | 6.129 × 10−2 | |

| 1000 | 0.855 | 9.378 × 10−1 | 7.909 × 10−2 |

| Cohort | TF | 250 kb | 500 kb | 750 kb | 1000 kb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACC | AP-2ε | 84/622 (13.5%) | 135/1058 (12.8%) | 184/1444 (12.7%) | 223/1822 (12.2%) |

| DLBC | AP-2ε | 60/544 (11.0%) | 100/939 (10.6%) | 137/1255 (10.9%) | 163/1538 (10.6%) |

| STAD | AP-2β | 3/134 (2.24%) | 8/239 (3.35%) | 12/374 (3.21%) | 17/469 (3.62%) |

| TCGA Cohort Abbreviation | Full Disease Name/Description | Number of Samples Included in This Study, Considering Microbiota Data Availability |

|---|---|---|

| ACC | Adrenocortical carcinoma | 76 |

| BLCA | Bladder urothelial carcinoma | 395 |

| BRCA | Breast invasive carcinoma | 1090 |

| CESC | Cervical and endocervical cancers | 293 |

| CHOL | Cholangiocarcinoma | 33 |

| COAD | Colon adenocarcinoma | 456 |

| DLBC | Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | 47 |

| ESCA | Esophageal carcinoma | 162 |

| GBM | Glioblastoma multiforme | 154 |

| HNSC | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | 500 |

| KICH | Kidney chromophobe | 65 |

| KIRC | Kidney renal clear cell carcinoma | 532 |

| KIRP | Kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma | 288 |

| LAML | Acute myeloid leukemia | 146 |

| LGG | Lower grade glioma | 510 |

| LIHC | Liver hepatocellular carcinoma | 361 |

| LUAD | Lung adenocarcinoma | 496 |

| LUSC | Lung squamous cell carcinoma | 495 |

| MESO | Mesothelioma | 85 |

| OV | Ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma | 373 |

| PAAD | Pancreatic adenocarcinoma | 176 |

| PCPG | Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma | 179 |

| PRAD | Prostate adenocarcinoma | 484 |

| READ | Rectum adenocarcinoma | 166 |

| SARC | Sarcoma | 253 |

| SKCM | Skin cutaneous melanoma | 103 |

| STAD | Stomach adenocarcinoma | 375 |

| TGCT | Testicular germ cell tumors | 135 |

| THCA | Thyroid carcinoma | 502 |

| THYM | Thymoma | 116 |

| UCEC | Uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma | 545 |

| UCS | Uterine carcinosarcoma | 56 |

| UVM | Uveal melanoma | 79 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kołat, D.; Gromek, P.; Zhao, L.-Y.; Kałuzińska-Kołat, Ż.; Kciuk, M.; Kontek, R.; Płuciennik, E. Intratumoral Microbiota Correlates with AP-2 Expression: A Pan-Cancer Map with Cohort-Specific Prognostic and Molecular Footprints. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11587. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311587

Kołat D, Gromek P, Zhao L-Y, Kałuzińska-Kołat Ż, Kciuk M, Kontek R, Płuciennik E. Intratumoral Microbiota Correlates with AP-2 Expression: A Pan-Cancer Map with Cohort-Specific Prognostic and Molecular Footprints. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11587. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311587

Chicago/Turabian StyleKołat, Damian, Piotr Gromek, Lin-Yong Zhao, Żaneta Kałuzińska-Kołat, Mateusz Kciuk, Renata Kontek, and Elżbieta Płuciennik. 2025. "Intratumoral Microbiota Correlates with AP-2 Expression: A Pan-Cancer Map with Cohort-Specific Prognostic and Molecular Footprints" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11587. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311587

APA StyleKołat, D., Gromek, P., Zhao, L.-Y., Kałuzińska-Kołat, Ż., Kciuk, M., Kontek, R., & Płuciennik, E. (2025). Intratumoral Microbiota Correlates with AP-2 Expression: A Pan-Cancer Map with Cohort-Specific Prognostic and Molecular Footprints. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11587. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311587