Optical Limiting in a Novel Photonic Material—DNA Biopolymer Functionalized with the Spirulina Natural Dye

Abstract

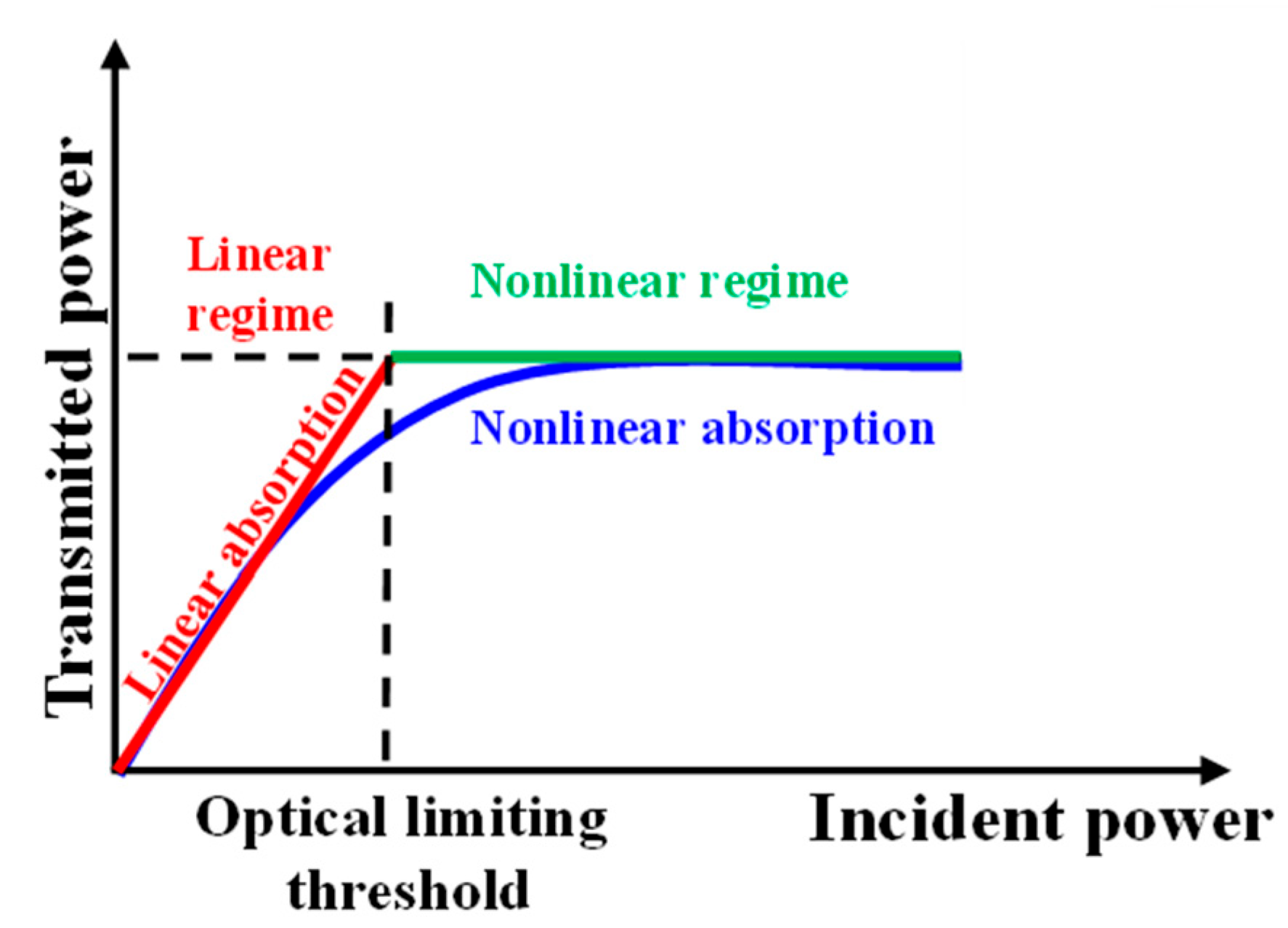

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of the Investigated Samples

2.2. Linear Optical Properties

2.2.1. Refractometry and UV–VIS–NIR Spectroscopy

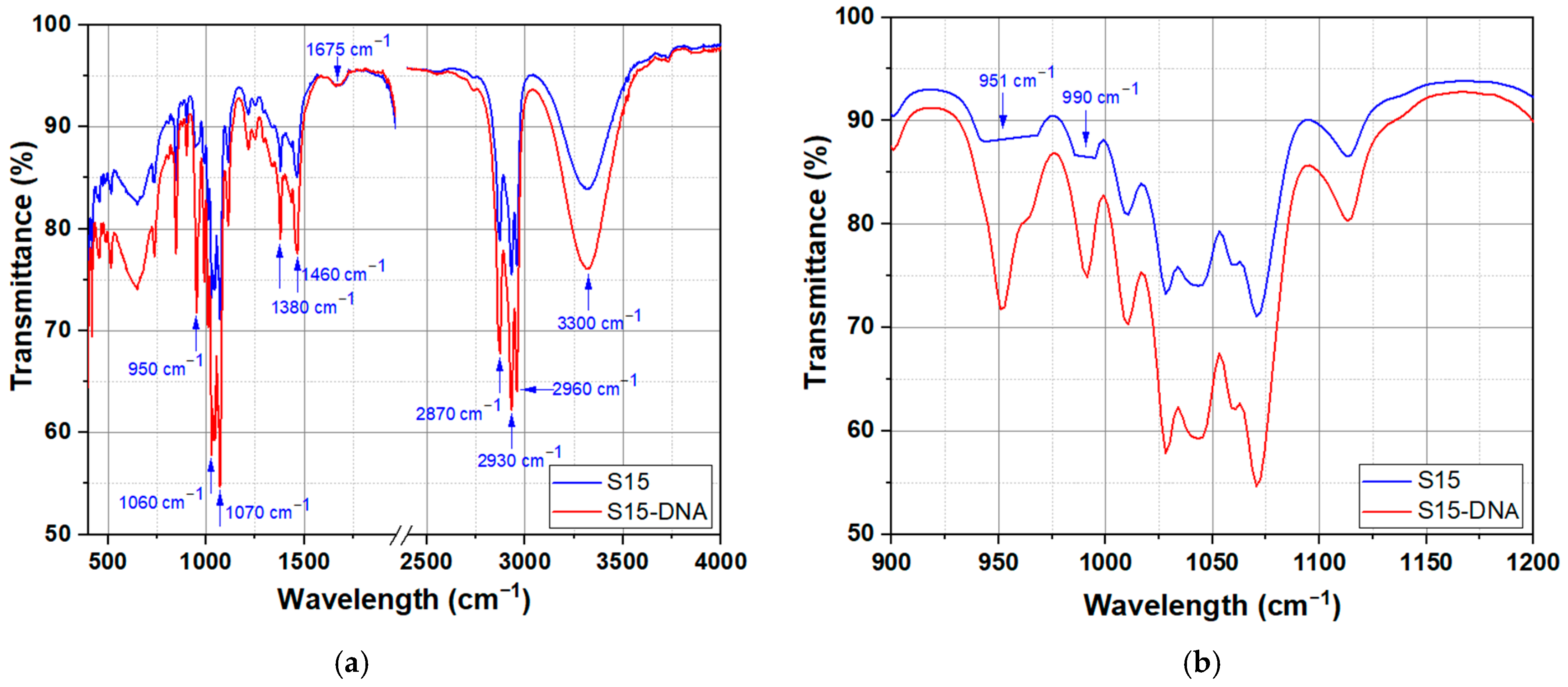

2.2.2. FTIR Spectroscopy

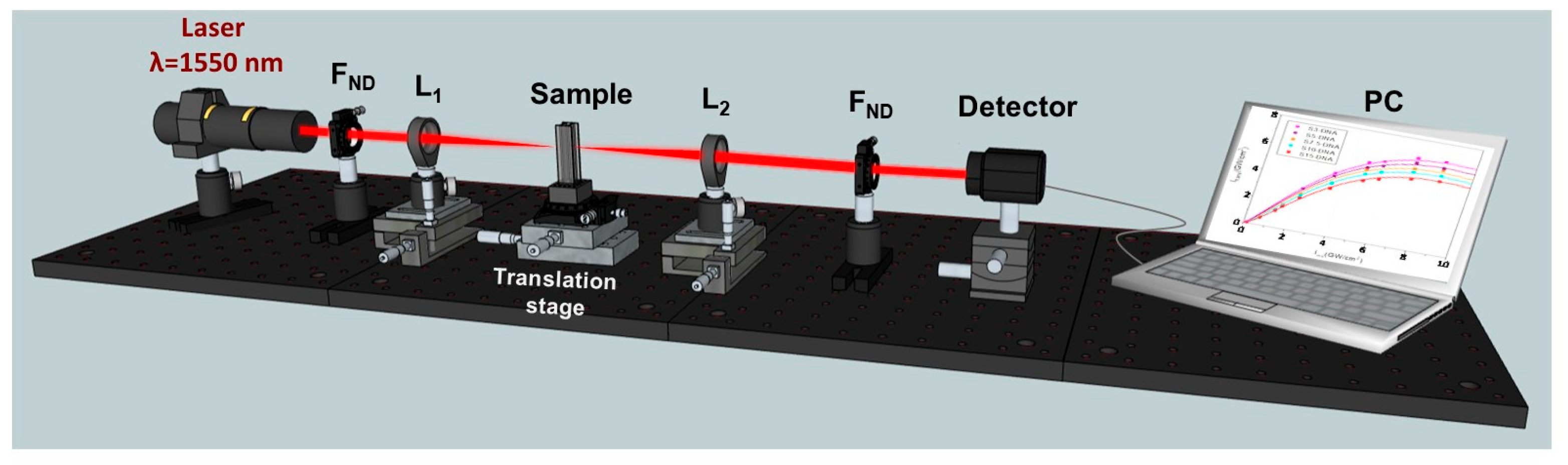

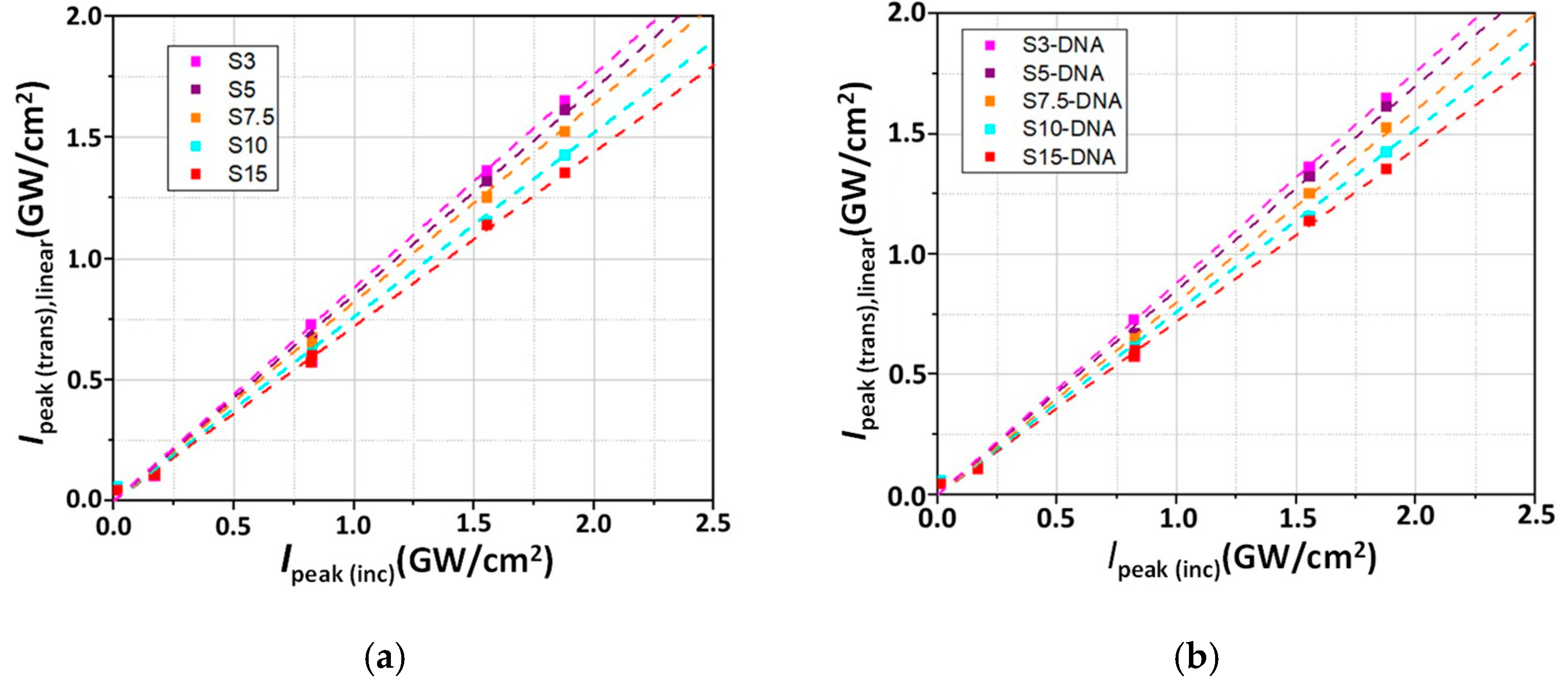

2.3. Nonlinear Optical Properties Investigated by the I-Scan Method

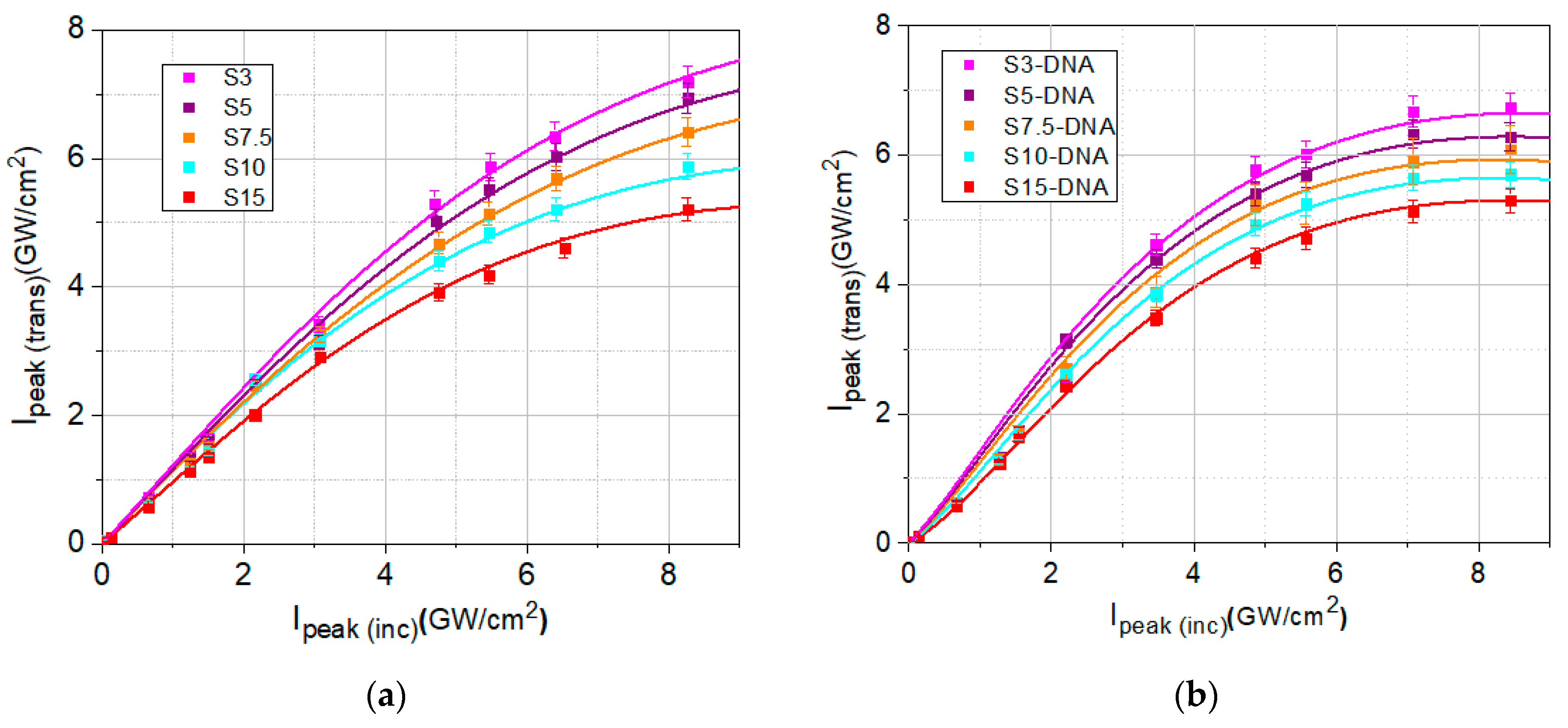

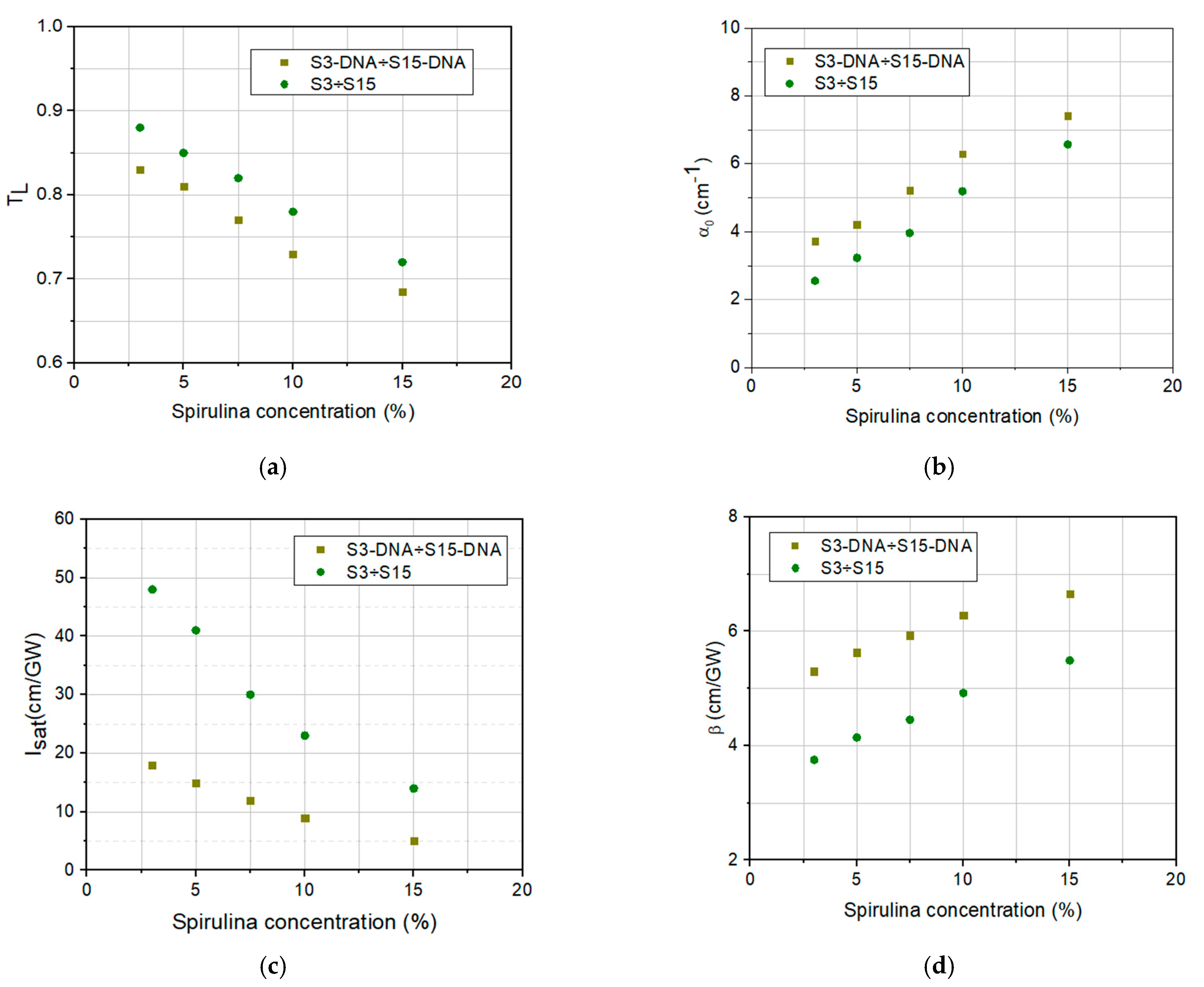

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Garmire, E. Nonlinear optics in daily life. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 30532–30544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, R.W. Nonlinear Optics, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-0-12-369470-6. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, T.; Hagan, D.J.; Dogariu, A.; Said, A.A.; Van Stryland, E.W. Optimization of optical limiting devices based on excited-state absorption. Appl. Opt. 1997, 36, 4110–4122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, B.; Chen, Y. Recent Progress in Two-Dimensional Nanomaterials for Laser Protection. Chemistry 2019, 1, 17–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbinta-Patrascu, M.-E.; Iordache, S.M. DNA—The fascinating biomacromolecule in optoelectronics and photonics applications. J. Optoelectron. Adv. Mater. 2022, 24, 563–575. [Google Scholar]

- Lundén, H.; Glimsdal, E.; Lindgren, M.; Lopesa, C. How to assess good candidate molecules for self-activated optical power limiting. Opt. Eng. 2018, 57, 030802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, D.; Calvete, M.J.F.; Hanack, M. Nonlinear Optical Materials for the Smart Filtering of Optical Radiation. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 13043–13233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, A.M.; Rau, I.; Kajzar, F.; Simion, A.M.; Pirvu, C.; Radu, N.; Simion, C. Natural materials with enhanced optical damage threshold. Opt. Mater. 2018, 86, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Fu, Y.; Wang, D.; Wei, Y.; Kobayashi, N.; Minari, T. DNA as Functional Material in Organic-Based Electronics. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petris, A.; Vasiliu, I.C.; Gheorghe, P.; Iordache, A.M.; Ionel, L.; Rusen, L.; Iordache, S.; Elisa, M.; Trusca, R.; Ulieru, D.; et al. Graphene Oxide-Based Silico-Phosphate Composite Films for Optical Limiting of Ultrashort Near-Infrared Laser Pulses. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaros, N.; Aloukos, P.; Kolokithas-Ntoukas, A.; Bakandritsos, A.; Szabo, T.; Zboril, R.; Couris, S. Nonlinear Optical Properties and Broadband Optical Power Limiting Action of Graphene Oxide Colloids. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 6842–6850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.F.; Polavarapu, L.; Neo, S.T.; Venkatesan, T.; Xu, Q. Graphene Oxides as Tunable Broadband Nonlinear Optical Materials for Femtosecond Laser Pulses. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2012, 3, 785–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.P.; Riggs, J.E. Organic and inorganic optical limiting materials. From fullerenes to nanoparticles. Int. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1999, 18, 43–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Werner, J.B. Inorganic and hybrid nanostructures for optical limiting. J. Opt. A Pure Appl. Opt. 2009, 11, 024001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghe, P.; Petris, A.; Anton, A.M. Optical limiting properties of DNA biopolymer doped with natural dyes. Polymers 2024, 16, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anusha, B.; Devanesan, S.; AlSalhi, M.S.; Murali, G.; Vimalan, M.; Madhu, S.; Jeyaram, S. A promising nonlinear optical feature in natural green dye for optical limiting applications. J. Opt. 2025, 54, 979–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, S.J.; Chaitanya Kumar, S.; Giribabu, L.; Venugopal Rao, S. Large third-order optical nonlinearity and optical limiting in symmetric and unsymmetrical phthalocyanines studied using Z-scan. Opt. Commun. 2007, 280, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aithal, S.; Aithal, P.S.; Bhat, G.K. CW Optical Limiting Study in Disperse Yellow Dye-Doped PMMA-MA Polymer Films. IRA-Int. J. Appl. Sci. 2016, 5, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaplicki, R.; Krupka, O.; Essaïdi, Z.; El-Ghayoury, A.; Kajzar, F.; Grote, J.G.; Sahraoui, B. Grating inscription in picosecond regime in thin films of functionalized DNA. Opt. Express 2007, 15, 15268–15273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grote, J. Biopolymer materials show promise for electronics and photonics applications. SPIE Newsroom 2008, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steckl, A.J. DNA—A new material for photonics? Nat. Photonics 2007, 1, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grote, J.G. Materials Science of DNA—Conclusions and Perspectives. In Materials Science of DNA; Jin, J., II, Grote, J., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011; pp. 311–317. [Google Scholar]

- Khazaeinezhad, R.; Kassani, S.H.; Paulson, B.; Jeong, H.; Gwak, J.; Rotermund, F.; Yeom, D.; Oh, K. Ultrafast nonlinear optical properties of thin-solid DNA film and their application as a saturable absorber in femtosecond mode-locked fiber laser. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheorghe, P.; Petris, A.; Vlad, V.I.; Rau, I.; Kajzar, F.; Manea, A.M. Temporal evolution of the laser recording of gratings in DNA-CTMA:Rh610 films. Rom. Rep. Phys. 2015, 67, 1412–1420. [Google Scholar]

- Miniewicz, A.; Kochalska, A.; Mysliwiec, J.; Samoc, A.; Samoc, M.; Grote, J.G. Deoxyribonucleic acid-based photochromic material for fast dynamic holography. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 91, 041118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petris, A.; Gheorghe, P.S.; Rau, I.; Manea-Saghin, A.M.; Kajzar, F. All-optical spatial phase modulation in films of dye-doped DNA biopolymer. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 110, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petris, A.; Gheorghe, P.; Vlad, V.I.; Rau, I.; Kajzar, F. Interferometric method for the study of spatial phase modulation induced by light in dye-doped DNA complexes. Rom. Rep. Phys. 2015, 67, 1373–1382. [Google Scholar]

- Bazaru Rujoiu, T.; Petris, A.; Vlad, V.I.; Rau, I.; Manea, A.M.; Kajzar, F. Lasing in DNA–CTMA doped with Rhodamine 610 in butanol. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 13104–13111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Li, W.; Hagen, J.A.; Zhou, Y.; Klotzkin, D.; Grote, J.G.; Steckl, A.J. Photoluminescence and lasing from deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) thin films doped with sulforhodamine. Appl. Opt. 2007, 46, 1507–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mindroiu, M.; Manea, A.-M.; Rau, I.; Grote, J.G.; Oliveira, H.; Pawlicka, A.; Kajzar, F. DNA- and DNA-CTMA: Novel bio-nanomaterials for application in photonics and in electronics. Proc. SPIE 2013, 8882, 888202. [Google Scholar]

- Rau, I.; Grote, J.G.; Kajzar, F.; Pawlicka, A. DNA–novel nanomaterial for applications in photonics and in electronics. Comptes Rendus Phys. 2012, 13, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizioł, J.; Fiedor, J.; Pagacz, J.; Hebda, E.; Marzec, M.; Gondek, E.; Kityk, I.V. DNA-hexadecyltrimethyl ammonium chloride complex with enhanced thermostability as promising electronic and optoelectronic material. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2017, 28, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, A.-M.; Rau, I.; Kajzar, F.; Simion, A.-M.; Simion, C. Third-order nonlinear optical properties of DNA-based biopolymers thin films doped with selected natural chromophores. Opt. Mater. 2019, 88, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mircea, M.L.; Manea, A.M.; Kajzar, F.; Rau, I. Tuning NLO susceptibility in functionalized DNA. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2016, 4, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, I.; Tane, A.; Zgarian, R.; Meghea, A.; Grote, J.G.; Kajzar, F. Stability of Selected Chromophores in Biopolymer Matrix. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 2012, 554, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petris, A.; Gheorghe, P.; Rau, I. DNA–CTMA matrix influence on Rhodamine 610 light emission in thin films. Polymers 2023, 15, 3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahraoui, B.; Pranaitis, M.; Gindre, D.; Niziol, J.; Kazukauskas, V. Opportunities of deoxyribonucleic acid complexes composites for nonlinear optical applications. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 110, 083117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petris, A.; Gheorghe, P.; Rau, I. Influence of continuous wave laser light at 532 nm on transmittance and on photoluminescence of DNA-CTMA-RhB solutions. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dancus, I.; Vlad, V.I.; Petris, A.; Bazaru Rujoiu, T.; Rau, I.; Kajzar, F.; Meghea, A.; Tane, A. Z-Scan and I-Scan methods for characterization of DNA Optical Nonlinearities. Rom. Rep. Phys. 2013, 65, 966. [Google Scholar]

- Minea, A.A. State of the art in PEG-based heat transfer fluids and their suspensions with nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Sun, Y.; Hu, F.; Liu, D.; Zhang, X.; Ren, J.; Guo, H.; Shalash, M.; He, M.; Hou, H.; et al. An overview of polymer-based thermally conductive functional materials. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 218, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldoveanu, M.; Popescu, R.; Pîrvu, C.; Grote, J.G.; Kajzar, F.; Rau, I. Biopolymer thin films for optoelectronics applications. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 2010, 522, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramonov, L.E. Absorption Coefficient Spectrum and Intracellular Pigment, Concentration by an Example of Spirulina platensis. Atmos. Ocean. Opt. 2018, 31, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malletzidou, L.; Kyratzopoulou, E.; Kyzaki, N.; Nerantzis, E.; Kazakis, N.A. Near-Infrared Spectroscopy for Growth Estimation of Spirulina platensis Cultures. Methods Protoc. 2024, 7, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dancus, I.; Petris, A.; Doia, P.S.; Fazio, E.; Vlad, V.I. Z-Scan Measurement of Thermal Third-Order Optical Nonlinearities. Proc. SPIE 2007, 6785, 67851F. [Google Scholar]

- Sheik-Bahae, M.; Hasselbeck, M.P. Third-order optical nonlinearities. In OSA Handbook of Optics 2000; Volume IV-Optical Properties of Materials, Nonlinear Optics, Quantum Optics, Part II-Nonlinear Optics, Chapter 17-Third-Order Optical Nonlinearities; The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sheik-Bahae, M.; Said, A.A.; Wei, T.; Hagan, D.J.; Van Stryland, E.W. Sensitive measurement of optical nonlinearities using a single beam. IEEE. J. Quantum Electron. 1990, 26, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, A.; Liu, H.; Jassemnejad, B.; Appling, D.; Powell, R.C.; Song, J.J. Intensity scan and two photon absorption and nonlinear refraction of C60 in toluene. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1996, 68, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Córdova, J.Z.; Arano-Martinez, J.A.; Mercado-Zúñiga, C.; Martínez-González, C.L.; Torres-Torres, C. Predicting the Multiphotonic Absorption in Graphene by Machine Learning. AI 2024, 5, 2203–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petris, A.; Vlad, I.V.; Gheorghe, P.; Rau, I.; Kajzar, F. All-Optical Spatial Light Modulator Based on Functionalized DNA. Patent RO 132685 B1, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Grote, J.G.; Diggs, D.E.; Nelson, R.L.; Zetts, J.S.; Hopkins, F.K.; Ogata, N.; Hagen, J.A.; Heckman, E.; Yaney, P.P.; Stone, M.O.; et al. DNA photonics [deoxyribonucleic acid]. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 2005, 426, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prenting, M.M.; Shilikin, M.; Dreier, T.; Schultz, C.; Endres, T. Characterization of tracers for two-color laser-induced fluorescence thermometry of liquid-phase temperature in ethanol, 2–ethylhexanoic-acid/ethanol mixtures, 1-butanol, and o-xylene: Supplement. Appl. Opt. 2021, 60, C98–C113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, H.; Spaeth, H.; Linhard, V.N.L.; Steckl, A.J. Role of Surfactants in the Interaction of Dye Molecules in Natural DNA Polymers. Langmuir 2009, 25, 11698–11702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marechal, Y. The Hydrogen Bond and Water Molecule; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.Y.; Nagamani, S.; Liu, L.; Elghazaly, A.H.; Solin, N.; Inganäs, O. A DNA and Self-Doped Conjugated Polyelectrolyte Assembled for Organic Optoelectronics and Bioelectronics. Biomacromolecules 2020, 21, 1214–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, W.; Zhan, M.; Li, Z. Organically Modifying and Modeling Analysis of Montmorillonites. Mater. Des. 2003, 24, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Shan, C.; Shen, W.; Jia, X. Preparation of “natural” diamonds by HPHT annealing of synthetic diamonds. CrystEngComm 2018, 20, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivan, R.; Popescu, C.; Antohe, V.A.; Antohe, S.; Negrila, C.; Logofatu, C.; Pérez del Pino, A.; György, E. Iron oxide/hydroxide–nitrogen doped graphene-like visible-light active photocatalytic layers for antibiotics removal from wastewater. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celekli, A.; Yavuzatmaca, M.; Bozkurt, H. Kinetic and equilibrium studies on biosorption of reactive red 120 from aqueous solution on Spirogyra majuscula. Chem. Eng. J. 2009, 152, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celekli, A.; Yavuzatmaca, M.; Bozkurt, H. An eco-friendly process: Predictive modelling of copper adsorption from aqueous solution on Spirulina platensis. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 173, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhu, C.; Li, Z.; Zhou, H. Screening of Spirulina strains for high copper adsorption capacity through Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 952597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paschotta, R. RP Photonics Encyclopedia. Available online: www.rp-photonics.com (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Cacheux-Luna, O.O.; Bravo-Hernandez, A.A.; Garduno-Mejia, J.; Rosete-Aguilar, M.; Aupart-Acosta, A.; Ruiz, C.; Delgado-Aguillon, J. Two-photon absorption scan technique to detect focal shift in the nonlinear regime of focused femtosecond pulses. Opt. Express 2025, 33, 40960–40968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://refractiveindex.info/?shelf=main&book=H2O&page=Hale (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Miller, M.J.; Mott, A.G.; Ketchel, B.P. General Optical-Limiting Requirements, Army Research Laboratory ARL-TR-1958. Proc. SPIE 1999, 3472, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchouit, K.; Derkowska, B.; Migalska-Zalas, A.; Abed, S.; Benali-Cherif, N.; Sahraoui, B. Nonlinear optical properties of selected natural pigments extracted from spinach: Carotenoids. Dye. Pigment. 2010, 86, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Baker, A.; Boltaev, G.S.; Piatkowski, P.; Khamis, M.; Alnaser, A.S. Nonlinear optical properties and transient absorption in Hibiscus Sabdariffa dye solution probed with femtosecond pulses. Opt. Mater. 2023, 138, 113728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Denomination of Samples | Spirulina Concentration in Solution g/L |

|---|---|

| S3/S3-DNA | 3 |

| S5/S5-DNA | 5 |

| S7.5/S7.5-DNA | 7.5 |

| S10/S10-DNA | 10 |

| S15/S15-DNA | 15 |

| Sample | TL | α0 (cm−1) | Isat (GW/cm2) | β (cm/GW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S3/S3-DNA | 0.88/0.83 | 2.55/3.73 | 48/18 | 3.75/5.30 |

| S5/S5-DNA | 0.85/0.81 | 3.25/4.21 | 41/15 | 4.14/5.63 |

| S7.5/S7.5-DNA | 0.82/0.77 | 3.96/5.22 | 30/12 | 4.45/5.93 |

| S10/S10-DNA | 0.77/0.73 | 5.22/6.29 | 23/9 | 4.92/6.28 |

| S15/S15-DNA | 0.72/0.69 | 6.57/7.42 | 14/5 | 5.49/6.63 |

| Nonlinear Compound/Dye | β (cm/GW) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Turmeric–DNA/Turmeric | 4/3.4 | [15] |

| Spinach (Violxanthine dye) | 1.87 | [66] |

| Hibiscus Sabdariffa | 2.1 × 10−4 | [67] |

| Spirulina–DNA/Spirulina | 6.63/5.49 | present work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gheorghe, P.; Petris, A. Optical Limiting in a Novel Photonic Material—DNA Biopolymer Functionalized with the Spirulina Natural Dye. Molecules 2025, 30, 4577. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234577

Gheorghe P, Petris A. Optical Limiting in a Novel Photonic Material—DNA Biopolymer Functionalized with the Spirulina Natural Dye. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4577. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234577

Chicago/Turabian StyleGheorghe, Petronela, and Adrian Petris. 2025. "Optical Limiting in a Novel Photonic Material—DNA Biopolymer Functionalized with the Spirulina Natural Dye" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4577. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234577

APA StyleGheorghe, P., & Petris, A. (2025). Optical Limiting in a Novel Photonic Material—DNA Biopolymer Functionalized with the Spirulina Natural Dye. Molecules, 30(23), 4577. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234577