Sex on the Screen: A Content Analysis of Free Internet Pornography Depicting Mixed-Sex Threesomes from 2012–2020

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Sexual Script Theory: A Theoretical Mechanism through Which Internet Pornography Influences Sexual Behavior

1.2. Internet Pornography and Shifting Sexual Scripts

1.3. Internet Pornography Depicting Mixed-Sex Threesomes

1.4. Content of Free Internet Pornography

1.5. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Websites

2.2. Videos

2.3. Coding System

2.4. Descriptive and Demographic Information

2.4.1. Sexual Behaviors

2.4.2. Aggression

2.4.3. Initiation

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Characteristics

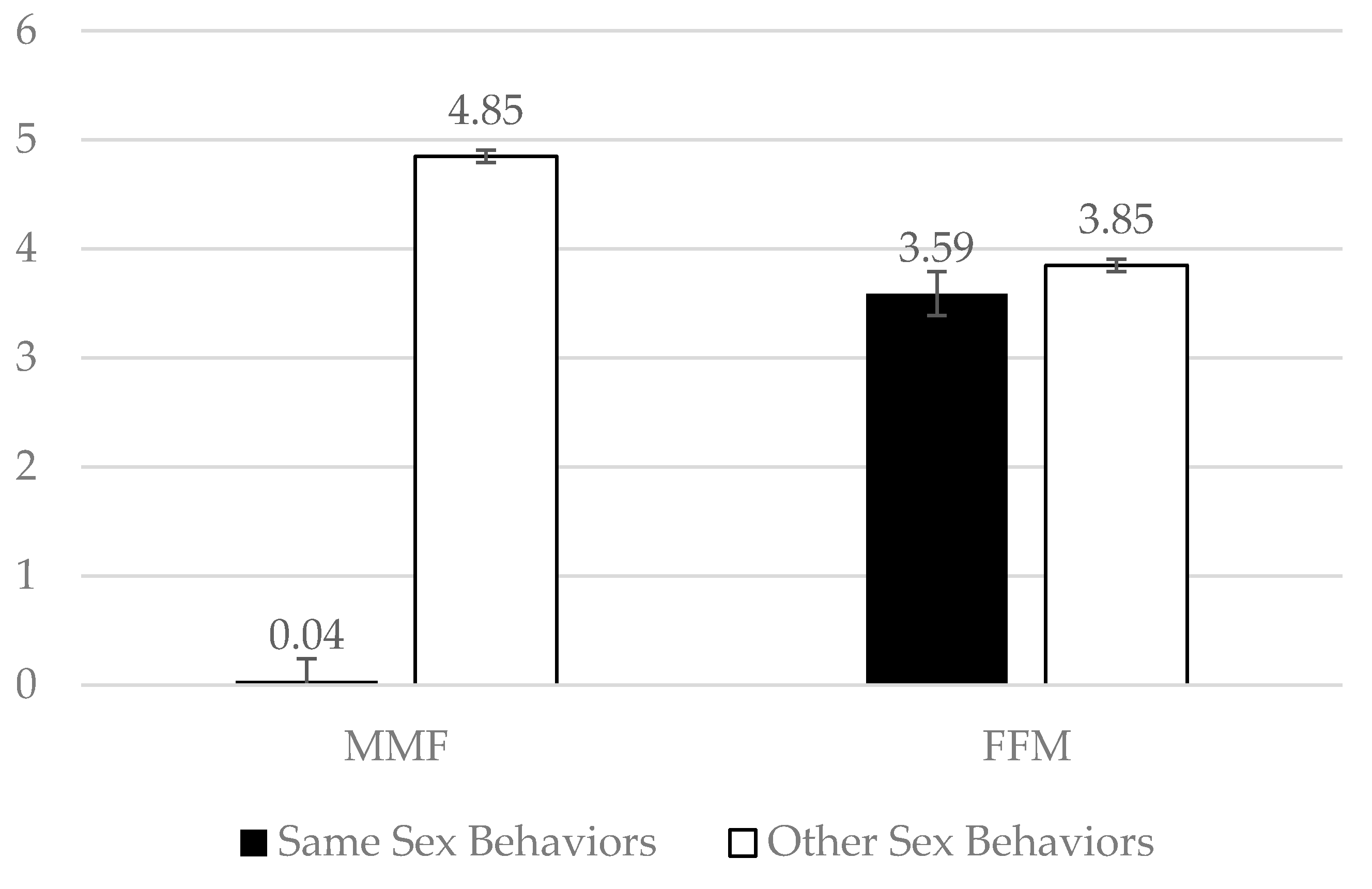

3.2. Sexual Behaviors

3.3. Sex Differences

3.3.1. Aggression

3.3.2. Sexual Initiation

4. Discussion

4.1. Same-Sex versus Other-Sex Behaviors and Sexual Script Theory

4.2. Aggression, Initiation, and Sexual Script Theory

4.3. Implications

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peter, J.; Valkenburg, P. The influence of sexually explicit internet material on sexual risk behavior: A comparison of adolescents and adults. J. Health Commun. 2011, 16, 750–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Döring, N.M. The internet’s impact on sexuality: A critical review of 15 years of research. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2009, 25, 1089–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano, I.; Eaton, N.R.; O’Leary, K.D. Pornography consumption, modality and function in a large internet sample. J. Sex Res. 2018, 57, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pornhub. The 2019 Year in Review; Pornhub Insights: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2019; Available online: https://www.pornhub.com/insights/2019-year-in-review#traffic (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- Pornhub. Coronavirus Update—April 14; Pornhub Insights: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2020; Available online: https://www.pornhub.com/insights/coronavirus-update-april-14 (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- Gagnon, J.H.; Simon, W. Sexual Conduct: The Social Sources of Human Sexuality, 2nd ed.; Aldine: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, W.; Gagnon, J. Sex talk-public and private. ETC Rev. Gen. Semant. 1968, 25, 173–191. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, W.; Gagnon, J.H. On psychosexual development. In Handbook of Socialization Theory and Research; Goslin, D.A., Ed.; Rand McNally: New York, NY, USA, 1969; pp. 733–752. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.D.; L’Engle, K.L. X-rated: Sexual attitudes and behaviors associated with U.S. early adolescents’ exposure to sexually explicit media. Commun. Res. 2009, 36, 129–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Lee, C.H. Exposure to internet pornography and sexually aggressive behaviour: Protective roles of social support among Korean adolescents. J. Sex. Aggress. 2019, 25, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubbs, J.B.; Kraus, S.W. Pornography use and psychological science: A call for consideration. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 30, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaillancourt-Morel, M.P.; Rosen, N.O.; Štulhofer, A.; Bosisio, M.; Bergeron, S. Pornography use and sexual health among same-sex and mixed-sex couples: An event-level dyadic analysis. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2021, 50, 667–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bőthe, B.; Vaillancourt-Morel, M.P.; Bergeron, S.; Demetrovics, Z. Problematic and non-problematic pornography use among LGBTQ adolescents: A systematic literature review. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2019, 6, 478–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, J.B.; Packham, A. The effects of state-mandated abstinence-based sex education on teen health outcomes. Health Econ. 2017, 26, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grov, C.; Gillespie, B.; Royce, T.; Lever, J. Perceived consequences of casual online sexual activities on heterosexual relationships: A U.S. online survey. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2011, 40, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litsou, K.; Byron, P.; McKee, A.; Ingham, R. Learning from pornography: Results of a mixed methods systematic review. Sex Educ. 2021, 21, 236–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, J.; Valkenburg, P. Adolescents’ use of sexually explicit internet material and sexual uncertainty: The role of involvement and gender. Commun. Monogr. 2010, 77, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, E.F.; Beckmeyer, J.J.; Herbenick, D.; Fu, T.C.; Dodge, B.; Fortenberry, J.D. The prevalence of using pornography for information about how to have sex: Findings from a nationally representative survey of US adolescents and young adults. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2021, 50, 629–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohut, T.; Fisher, W.A.; Campbell, L. Perceived effects of pornography on the couple relationship: Initial findings of open-ended, participant-informed, “bottom-up” research. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2017, 46, 585–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Döring, N.M.; Daneback, K.; Shaughnessy, K.; Grov, C.; Byers, E.S. Online sexual activity experiences among college students: A four-country comparison. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2017, 46, 1641–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Observational learning. In Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Bandura, A., Ed.; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.L.; Sorsoli, C.L.; Collins, K.; Zylbergold, B.A.; Schooler, D.; Tolman, D.L. From sex to sexuality: Exposing the heterosexual script on primetime network television. J. Sex Res. 2007, 44, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsch, A.C.; Murnen, S.K. “Hot” girls and “cool dudes”: Examining the prevalence of the heterosexual script in American children’s television media. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 2015, 4, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.; Scott, S. The personal is still political: Heterosexuality, feminism, and monogamy. Fem. Psychol. 2004, 14, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubrey, J.S. Sex and Punishment: An examination of sexual consequences and the sexual double standards in teen programming. Sex Roles 2004, 50, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolman, D.L.; Kim, J.L.; Schooler, D.; Sorsoli, C.L. Rethinking the associations between television viewing and adolescent sexuality development: Bringing gender into focus. J. Adolesc. Health 2007, 40, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maas, M.K.; Shearer, C.L.; Gillen, M.M.; Lefkowitz, E.S. Sex rules: Emerging adults’ perceptions of gender’s impact on sexuality. Sex. Cult. 2015, 19, 617–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Masters, N.T.; Casey, E.; Wells, E.A.; Morrison, D.M. Sexual scripts among young heterosexually active men and women: Continuity and change. J. Sex Res. 2013, 50, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Conley, T.D.; Moors, A.C.; Matsick, J.L.; Ziegler, A. The fewer the merrier? Assessing stigma surrounding consensually non-monogamous romantic relationships. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 2013, 13, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Conley, T.D.; Matsick, J.L.; Moors, A.C.; Ziegler, A. Investigation of consensually nonmonogamous relationships: Theories, methods, and new directions. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 12, 205–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bettinsoli, M.L.; Suppes, A.; Napier, J.L. Predictors of attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women in 23 Countries. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2020, 11, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, L.M. Female bisexuality from adolescence to adulthood: Results from a 10-year longitudinal study. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 44, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamond, L.M. Sexual fluidity in male and females. Curr. Sex. Health Rep. 2016, 8, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, S.G.; Mattson, R.E.; Chen, M.H.; Hardesty, M.; Merriwether, A.; Young, S.R.; Parker, M.M. Trending Queer: Emerging Adults and the Growing Resistance to Compulsory Heterosexuality. In Sexuality in Emerging Adulthood; Morgan, E., van Dulmen, M.H.M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick, N.B. Sexual scripts: Social and therapeutic implications. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2010, 25, 96–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Sherman, R.A.; Wells, B.E. Changes in American adults’ sexual behavior and attitudes, 1972–2012. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2015, 44, 2273–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, S.M.; Milkie, M.A.; Sayer, L.C.; Robinson, J.P. Is anyone doing the housework? Trends in gender division of household labor. Soc. Forces 2000, 79, 191–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, S.R.; Coulson, G.; Keddington, K.; Fincham, F.D. The influence of pornography on sexual scripts and hooking up among emerging adults in college. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2015, 44, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaassen, M.; Peter, J. Gender (in) equality in internet pornography: A content analysis of popular pornographic internet videos. J. Sex Res. 2015, 52, 721–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cooper, A. Sexuality and the internet: Surfing into the new millennium. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 1998, 1, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, E.A.; Miller, H.A.; Bouffard, J.A. Bridging the theoretical gap: Using sexual script theory to explain the relationship between pornography use and sexual coercion. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 5215–5238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyal, C.C.; Cossette, A.; Lapierre, V. Sexual fantasies in the general population. J. Sex. Med. 2015, 12, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.E.; Byers, E.S. Heterosexual young adults’ interest, attitudes, and experiences related to mixed-gender, multi-person sex. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2017, 46, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoats, R.; Anderson, E. ‘My partner was just all over her’: Jealousy, communication, and rules in mixed-sex threesomes. Cult. Health Sex. 2019, 21, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scoats, R.; Joseph, L.J.; Anderson, E. ‘I don’t mind watching him cum’: Heterosexual men, threesomes, and the erosion of the one-time rule of homosexuality. Sexualities 2018, 21, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, N.; Malic, V.; Paul, B.; Zhou, Y. Worse than objects: The depiction of black women and men and their sexual relationship in pornography. Gend. Issues 2021, 38, 100–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, S.; Monk-Turner, E.; Fish, J.N. Free adult internet web sites: How prevalent are degrading acts? Gend. Issues 2010, 27, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazandarani, F. Between a camera and a hard place: A content analysis of performer representation in heterosexual pornographic content. J. Sex Res. 2021, 58, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vannier, S.A.; Currie, A.B.; O’Sullivan, L.F. Schoolgirls and soccer moms: A content analysis of free “teen” and “MILF” online pornography. J. Sex Res. 2014, 51, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Paul, B. Lotus blossom or dragon lady: A content analysis of “Asian women” online pornography. Sex. Cult. Interdiscip. Q. 2016, 20, 1083–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, N.; Paul, B. From orgasms to spanking: A content analysis of the agentic and objectifying sexual scripts in feminist, for women, and mainstream pornography. Sex Roles 2017, 77, 639–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shor, E.; Golriz, G. Gender, race, and aggression in mainstream pornography. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2019, 48, 739–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taormino, T.; Penley, C.; Shimizu, C.; Miller-Young, M. (Eds.) The Feminist Porn Book: The Politics of Producing Pleasure; The Feminist Press at CUNY: New York City, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Downing, M.J., Jr.; Antebi, N.; Schrimshaw, E.W. Compulsive use of internet-based sexually explicit media: Adaptation and validation of the Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS). Addict. Behav. 2014, 39, 1126–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Seida, K.; Shor, E. Aggression and pleasure in opposite-sex and same-sex mainstream online pornography: A comparative content analysis of dyadic scenes. J. Sex Res. 2021, 58, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.; Bridges, A.; Johnson, J.A.; Ezzell, M.B. Pornography and the male sexual script: An analysis of consumption and sexual relations. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2016, 45, 983–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem. Med. 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Glascock, J. Gender roles on prime-time network television: Demographics and behaviors. J. Broadcasting Electron. Media 2001, 45, 656–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, A.J.; Sun, C.F.; Ezzell, M.B.; Johnson, J. Sexual scripts and the sexual behavior of men and women who use pornography. Sex. Media Soc. 2016, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahs, B. Compulsory bisexuality?: The challenges of modern sexual fluidity. J. Bisexuality 2009, 9, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hammack, P.L. Advancing the revolution in the science of sexual identity development. Hum. Dev. 2005, 48, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochman, J.M. The effects of nongender-role stereotyped, same-sex role models in storybooks on the self-esteem of children in grade three. Sex Roles 1996, 35, 711–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlford, K.E.; Lochman, J.E.; Barry, T.D. The relation between chosen role models and the self-esteem of men and women. Sex Roles 2004, 50, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, M.S.; Williams, C.J.; Kleiner, S.; Irizarry, Y. Pornography, normalization, and empowerment. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2010, 39, 1389–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworkin, S.L.; O’Sullivan, L. Actual versus desired initiation patterns among a sample of college men: Tapping disjunctures within traditional male sexual scripts. J. Sex Res. 2005, 42, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haselton, M.G.; Buss, D.M. Error management theory: A new perspective on biases in cross-sex mind reading. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 78, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brener, N.D.; Demissie, Z.; McManus, T.; Shanklin, S.L.; Queen, B.; Kann, L. School health profiles 2016: Characteristics of health programs among secondary schools. Cent. Dis. Control. Prev. 2017. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/profiles/pdf/2016/2016_profiles_report.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- Guttmacher Institute. Sex and HIV Education. 2020. Available online: https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/sex-and-hiv-education?gclid=CjwKCAjwv4_1BRAhEiwAtMDLsjjEJeUPqmKeutsIUjf06DDILUmW2j0hDXgImmlpbw3UZ1mgfe_S7xoCm8cQAvD_BwE (accessed on 17 July 2021).

| 2012 | 2015 | 2020 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMF | FFM | MMF | FFM | MMF | FFM | |

| Website Name | ||||||

| Bangyoulater.com | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dinotube.com | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Flyingjizz.com | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Freepornfull.com | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| Ixxx.com | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Nuvid.com | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Perfectgirls.net | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pornhub.com | 2 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Redtube.com | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| Sunporno.com | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tiava.com | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Tnalix.com | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Twilightsex.net | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tube8.com | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Xhamster.com | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 0 |

| Xnxx.com | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Xvideos.com | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Youjizz.com | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Youporn.com | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Total | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| 2012 | 2015 | 2020 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMF | FFM | MMF | FFM | MMF | FFM | |

| Same Sex | ||||||

| Kissing | 1 (4%) | 11 (44%) | 0 (0%) | 16 (64%) | 1 (4%) | 18 (72%) |

| Spanking | 0 (0%) | 2 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (32%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (24%) |

| Hand to breast | N/A | 16 (64%) | N/A | 17 (68%) | N/A | 21 (84%) |

| Mouth to breast | N/A | 12 (48%) | N/A | 12 (48%) | N/A | 16 (64%) |

| Oral sex | 0 (0%) | 12 (48%) | 0 (0%) | 15 (60%) | 1 (4%) | 17 (68%) |

| Analingus | 0 (0%) | 2 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (16%) | 0 (0%) | 10 (40%) |

| Anal penetration | 0 (0%) | N/A | 0 (0%) | N/A | 0 (0%) | N/A |

| Manual stimulation of genitals | 0 (0%) | 12 (48%) | 0 (0%) | 13 (52%) | 0 (0%) | 17 (68%) |

| Manual stimulation of anus | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (16%) |

| Use of sex toys | 0 (0%) | 2 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (8%) |

| Sexual paraphilia | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Sexual fetish | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) |

| Cuddling | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Mixed Sex | ||||||

| Kissing | 5 (20%) | 11 (44%) | 11 (44%) | 17 (68%) | 11 (44%) | 13 (32%) |

| Spanking | 11 (44%) | 10 (40%) | 10 (40%) | 11 (44%) | 10 (40%) | 5 (20%) |

| Hand to breast | 21 (84%) | 17 (68%) | 20 (80%) | 16 (64%) | 13 (32%) | 13 (32%) |

| Mouth to breast | 8 (32%) | 9 (36%) | 10 (40%) | 7 (28%) | 10 (40%) | 8 (32%) |

| Oral sex | 25 (100%) | 22 (88%) | 24 (96%) | 23 (92%) | 25 (100%) | 23 (925) |

| Analingus | 3 (12%) | 1 (4%) | 3 (12%) | 4 (16%) | 4 (16%) | 6 (24%) |

| Anal penetration | 16 (64%) | 6 (24%) | 10 (40%) | 4 (16%) | 17 (68%) | 4 (16%) |

| Manual stimulation of genitals | 23 (92%) | 16 (64%) | 20 (80%) | 15 (60%) | 25 (100%) | 17 (68%) |

| Manual stimulation of anus | 7 (28%) | 1 (4%) | 3 (12%) | 2 (8%) | 7 (28%) | 4 (16%) |

| Use of sex toys | 1 (4%) | 1 (4%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (12%) | 0 (0%) |

| Sexual paraphilia | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) |

| Sexual fetish | 2 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (16%) | 1 (4%) |

| Cuddling | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| 2012 | 2015 | 2020 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMF | FFM | MMF | FFM | MMF | FFM | |

| Era of video | ||||||

| Modern | 23 (92%) | 24 (96%) | 22 (88%) | 25 (100%) | 23 (92%) | 25 (100%) |

| Retro | 2 (8%) | 1 (4%) | 2 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (8%) | 0 (0%) |

| Filming location | ||||||

| Private | 13 (52%) | 20 (80%) | 19 (76%) | 22 (88%) | 21 (84%) | 23 (92%) |

| Public | 11 (44%) | 5 (20%) | 3 (12%) | 3 (12%) | 1 (4%) | 2 (8%) |

| Unclear | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (12%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (8%) | 0 (0%) |

| Actor race | ||||||

| White | 55 (73.33%) | 61 (81.33%) | 50 (66.67%) | 51 (68%) | 57 (76%) | 59 (78.67%) |

| Asian | 11 (14.67%) | 2 (2.67%) | 11 (14.67%) | 3 (4%) | 6 (8%) | 0 (0%) |

| Black | 6 (8%) | 10 (13.33%) | 5 (6.67%) | 5 (6.67%) | 7 (9.33%) | 1 (1.33%) |

| Latino/a | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.33%) | 4 (5.33%) | 3 (4%) | 5 (6.67%) | 8 (10.67%) |

| Other | 3 (4%) | 1 (1.33%) | 5 (6.67%) | 13 (17.33%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (9.33%) |

| Pubic hair (male) | ||||||

| No hair | 18 (36%) | 14 (56%) | 16 (32%) | 11 (44%) | 31 (62%) | 14 (56%) |

| Groomed (strip) | 2 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 11 (22%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) |

| Groomed (50%) | 25 (50%) | 11 (44%) | 11 (22%) | 9 (36%) | 9 (18%) | 5 (20%) |

| Ungroomed | 4 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (8%) | 2 (8%) | 8 (16%) | 3 (12%) |

| Unclear | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (16%) | 3 (12%) | 1 (2%) | 3 (12%) |

| Pubic hair (female) | ||||||

| No hair | 11 (44%) | 27 (54%) | 10 (40%) | 32 (64%) | 16 (64%) | 39 (78%) |

| Groomed (strip) | 6 (24%) | 9 (18%) | 5 (20%) | 8 (16%) | 3 (12%) | 3 (6%) |

| Groomed (50%) | 6 (24%) | 7 (14%) | 2 (8%) | 3 (6%) | 4 (16%) | 4 (8%) |

| Ungroomed | 2 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (8%) | 2 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) |

| Unclear | 0 (0%) | 7 (14%) | 6 (24%) | 5 (10%) | 2 (8%) | 3 (6%) |

| Visible ejaculation | 31 (62%) | 14 (56%) | 27 (54%) | 18 (72%) | 26 (52%) | 11 (44%) |

| Ejaculation location | ||||||

| Breast | 2 (6.45%) | 2 (14.30%) | 1 (3.70%) | 1 (5.56%) | 4 (15.38%) | 1 (9.09%) |

| Face/mouth | 23 (74.20%) | 8 (57.15%) | 15 (55.56%) | 13 (72.21%) | 15 (57.69%) | 5 (45.46%) |

| Vagina/vulva | 4 (12.90%) | 1 (7.15%) | 2 (7.41%) | 3 (16.67%) | 2 (7.69%) | 1 (9.09%) |

| Other | 2 (6.45%) | 3 (21.40%) | 9 (33.33%) | 1 (5.56%) | 5 (19.24%) | 4 (36.36%) |

| Breasts | ||||||

| Augmented | 4 (16%) | 10 (20%) | 2 (8%) | 19 (38%) | 7 (28%) | 14 (28%) |

| Natural | 18 (72%) | 33 (66%) | 20 (80%) | 26 (52%) | 15 (60%) | 33 (66%) |

| Unclear | 3 (12%) | 7 (14%) | 3 (12%) | 5 (10%) | 3 (12%) | 3 (6%) |

| Condom use | 4 (16%) | 1 (4%) | 5 (20%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| 2012 | 2015 | 2020 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMF | FFM | MMF | FFM | MMF | FFM | |

| Other-sex behaviors | 4.84 (1.55) | 3.76 (1.74) | 4.52 (1.81) | 3.96 (1.57) | 5.20 (2.16) | 3.76 (1.61) |

| Same-sex behaviors | 0.04 (0.20) | 1.43 (0.89) | 0.00 (0.00) | 1.77 (0.61) | 0.08 (0.28) | 2.08 (0.71) |

| 2012 | 2015 | 2020 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMF | FFM | MMF | FFM | MMF | FFM | |

| Aggression | ||||||

| Male aggressor (verbal) | 15 (60%) | 15 (60%) | 14 (56%) | 8 (32%) | 1 (4%) | 2 (8%) |

| Female aggressor (verbal) | 9 (36%) | 15 (60%) | 6 (24%) | 16 (64%) | 5 (20%) | 3 (12%) |

| Male aggressor (physical) | 22 (88%) | 14 (56%) | 20 (80%) | 14 (56%) | 9 (36%) | 4 (16%) |

| Female aggressor (physical) | 2 (8%) | 11 (44%) | 2 (8%) | 10 (40%) | 2 (8%) | 3 (12%) |

| Sexual initiation | ||||||

| Male initiator | 9 (36%) | 14 (56%) | 5 (20%) | 2 (8%) | 7 (28%) | 4 (16%) |

| Female initiator | 15 (60%) | 10 (40%) | 4 (16%) | 16 (64%) | 4 (16%) | 13 (52%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kulibert, D.; Moran, J.B.; Preman, S.; Vannier, S.A.; Thompson, A.E. Sex on the Screen: A Content Analysis of Free Internet Pornography Depicting Mixed-Sex Threesomes from 2012–2020. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2021, 11, 1555-1570. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe11040110

Kulibert D, Moran JB, Preman S, Vannier SA, Thompson AE. Sex on the Screen: A Content Analysis of Free Internet Pornography Depicting Mixed-Sex Threesomes from 2012–2020. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2021; 11(4):1555-1570. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe11040110

Chicago/Turabian StyleKulibert, Danica, James B. Moran, Sharayah Preman, Sarah A. Vannier, and Ashley E. Thompson. 2021. "Sex on the Screen: A Content Analysis of Free Internet Pornography Depicting Mixed-Sex Threesomes from 2012–2020" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 11, no. 4: 1555-1570. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe11040110