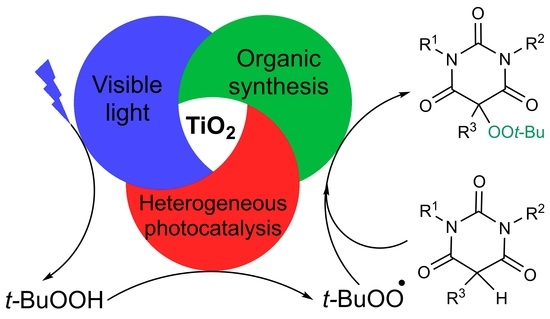

t-BuOOH/TiO2 Photocatalytic System as a Convenient Peroxyl Radical Source at Room Temperature under Visible Light and Its Application for the CH-Peroxidation of Barbituric Acids

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Study of Organic Peroxide Decomposition on TiO2 under Visible Light

2.2. Synthesis of Alkyl Peroxides from Barbituric Acids

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General

3.2. Experimental Procedures

3.3. Characterization Data of the Synthesized Products

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anaya-Rodríguez, F.; Durán-Álvarez, J.C.; Drisya, K.T.; Zanella, R. The Challenges of Integrating the Principles of Green Chemistry and Green Engineering to Heterogeneous Photocatalysis to Treat Water and Produce Green H2. Catalysts 2023, 13, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Han, X.; Nguyen, N.T.; Yang, L.; Zhou, X. TiO2-Based Photocatalysts for CO2 Reduction and Solar Fuel Generation. Chin. J. Catal. 2022, 43, 2500–2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel Ahmad, M.; Pandey, A.K.; Abd Rahim, N. Advancements in the Development of TiO2 Photoanodes and Its Fabrication Methods for Dye Sensitized Solar Cell (DSSC) Applications. A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 77, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Ding, B.; Kanda, H.; Usiobo, O.J.; Gallet, T.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Huang, H.; Sheng, J.; Liu, C.; et al. Single-Crystalline TiO2 Nanoparticles for Stable and Efficient Perovskite Modules. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2022, 17, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaya, U.I.; Abdullah, A.H. Heterogeneous Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Contaminants over Titanium Dioxide: A Review of Fundamentals, Progress and Problems. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 2008, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.N.; Haider, W. Heterogeneous Photocatalysis and Its Potential Applications in Water and Wastewater Treatment: A Review. Nanotechnology 2018, 29, 342001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozhevnikova, N.S.; Gorbunova, T.I.; Vorokh, A.S.; Pervova, M.G.; Zapevalov, A.Y.; Saloutin, V.I.; Chupakhin, O.N. Nanocrystalline TiO2 Doped by Small Amount of Pre-Synthesized Colloidal CdS Nanoparticles for Photocatalytic Degradation of 1,2,4-Trichlorobenzene. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2019, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, H.A.; Ditta, I.B.; Varghese, S.; Steele, A. Photocatalytic Disinfection Using Titanium Dioxide: Spectrum and Mechanism of Antimicrobial Activity. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 90, 1847–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakbolat, B.; Daulbayev, C.; Sultanov, F.; Beissenov, R.; Umirzakov, A.; Mereke, A.; Bekbaev, A.; Chuprakov, I. Recent Developments of TiO2-Based Photocatalysis in the Hydrogen Evolution and Photodegradation: A Review. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachina, A.K.; Popkov, V.I.; Seroglazova, A.S.; Enikeeva, M.O.; Kurenkova, A.Y.; Kozlova, E.A.; Gerasimov, E.Y.; Valeeva, A.A.; Rempel, A.A. Synthesis, Characterization and Photocatalytic Activity of Spherulite-like r-TiO2 in Hydrogen Evolution Reaction and Methyl Violet Photodegradation. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlova, E.A.; Parmon, V.N. Heterogeneous Semiconductor Photocatalysts for Hydrogen Production from Aqueous Solutions of Electron Donors. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2017, 86, 870–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhrutdinova, E.; Reutova, O.; Maliy, L.; Kharlamova, T.; Vodyankina, O.; Svetlichnyi, V. Laser-Based Synthesis of TiO2-Pt Photocatalysts for Hydrogen Generation. Materials 2022, 15, 7413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurenkova, A.Y.; Gerasimov, E.Y.; Saraev, A.A.; Kozlova, E.A. Photocatalysts Pt/TiO2 for CO2 Reduction under Ultraviolet Irradiation. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2023, 72, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eidsvåg, H.; Bentouba, S.; Vajeeston, P.; Yohi, S.; Velauthapillai, D. TiO2 as a Photocatalyst for Water Splitting—An Experimental and Theoretical Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Cen, J.; Xu, X.; Li, X. The Application of Heterogeneous Visible Light Photocatalysts in Organic Synthesis. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashimoto, S. Titanium-Dioxide-Based Visible-Light-Sensitive Photocatalysis: Mechanistic Insight and Applications. Catalysts 2019, 9, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhrutdinova, E.D.; Shabalina, A.V.; Gerasimova, M.A.; Nemoykina, A.L.; Vodyankina, O.V.; Svetlichnyi, V.A. Highly Defective Dark Nano Titanium Dioxide: Preparation via Pulsed Laser Ablation and Application. Materials 2020, 13, 2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyulyukin, M.; Filippov, T.; Cherepanova, S.; Solovyeva, M.; Prosvirin, I.; Bukhtiyarov, A.; Kozlov, D.; Selishchev, D. Synthesis, Characterization and Visible-Light Photocatalytic Activity of Solid and TiO2-Supported Uranium Oxycompounds. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wang, C.; Liu, W.; Chen, Q.; He, M. Visible-Light-Induced Aerobic Thiocyanation of Indoles Using Reusable TiO2/MoS2 Nanocomposite Photocatalyst. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 1771–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini-Sarvari, M.; Jafari, F.; Mohajeri, A.; Hassani, N. Cu2O/TiO2 Nanoparticles as Visible Light Photocatalysts Concerning C(Sp2)–P Bond Formation. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2018, 8, 4044–4051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Q.; He, M. Photocatalyzed Facile Synthesis of 2,5-Diaryl 1,3,4-Oxadiazoles with Polyaniline-g-C3N4-TiO2 Composite under Visible Light. Tetrahedron Lett. 2018, 59, 1489–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraev, A.A.; Kurenkova, A.Y.; Gerasimov, E.Y.; Kozlova, E.A. Broadening the Action Spectrum of TiO2-Based Photocatalysts to Visible Region by Substituting Platinum with Copper. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koohgard, M.; Hosseinpour, Z.; Sarvestani, A.M.; Hosseini-Sarvari, M. ARS–TiO2 Photocatalyzed Direct Functionalization of Sp2 C–H Bonds toward Thiocyanation and Cyclization Reactions under Visible Light. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 1401–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Jeong, J.; Fujita, K.; Yamamoto, A.; Yoshida, H. Anti-Markovnikov Hydroamination of Alkenes with Aqueous Ammonia by Metal-Loaded Titanium Oxide Photocatalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 12708–12714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, K.; Ghosh, S.C.; Panda, A.B. N-Doped Yellow TiO2 Hollow Sphere-Mediated Visible-Light-Driven Efficient Esterification of Alcohol and N -Hydroxyimides to Active Esters. Chem. Asian J. 2019, 14, 3205–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xian, C.; He, J.; He, Y.; Nie, J.; Yuan, Z.; Sun, J.; Martens, W.N.; Qin, J.; Zhu, H.-Y.; Zhang, Z. High Nitrile Yields of Aerobic Ammoxidation of Alcohols Achieved by Generating •O2− and Br• Radicals over Iron-Modified TiO2 Photocatalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 23321–23331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultana, S.; Kumar, G.; Sarma, L.S.; Venkatramu, V.; Gangi Reddy, N.C. Nitrogen-Doped TiO2 Nanotubes-Catalyzed Synthesis of Small D-π-A-Type Knoevenagel Adducts and Β-Enaminones. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 26, e202300032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalevskiy, N.; Selishchev, D.; Svintsitskiy, D.; Selishcheva, S.; Berezin, A.; Kozlov, D. Synergistic Effect of Polychromatic Radiation on Visible Light Activity of N-Doped TiO2 Photocatalyst. Catal. Commun. 2020, 134, 105841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalevskiy, N.; Svintsitskiy, D.; Cherepanova, S.; Yakushkin, S.; Martyanov, O.; Selishcheva, S.; Gribov, E.; Kozlov, D.; Selishchev, D. Visible-Light-Active N-Doped TiO2 Photocatalysts: Synthesis from TiOSO4, Characterization, and Enhancement of Stability Via Surface Modification. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.-L.; Hao, H.; Lang, X. Phenol–TiO2 Complex Photocatalysis: Visible Light-Driven Selective Oxidation of Amines into Imines in Air. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2019, 3, 488–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Liu, M.; Lu, T.; Gao, B.; Yang, X.; Zhou, L.; Li, H.; Su, Y. Base-Assisted Activation of Phenols in TiO2 Surface Complex under Visible Light Irradiation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2022, 431, 114005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shunxing, L.; Fengying, Z.; Wenlian, C.; Aiqin, H.; Yukun, X. Surface Modification of Nanometer Size TiO2 with Salicylic Acid for Photocatalytic Degradation of 4-Nitrophenol. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 135, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Xu, H.; Shi, J.-L.; Hao, H.; Yuan, H.; Lang, X. Salicylic Acid Complexed with TiO2 for Visible Light-Driven Selective Oxidation of Amines into Imines with Air. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 244, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ma, X.; Lang, X. Blue Light-Powered Hydroxynaphthoic Acid-Titanium Dioxide Photocatalysis for the Selective Aerobic Oxidation of Amines. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 602, 534–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Li, X.; Zhou, J.; Sheng, W.; Lang, X. Extending Aromatic Acids on TiO2 for Cooperative Photocatalysis with Triethylamine: Violet Light-Induced Selective Aerobic Oxidation of Sulfides. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 3733–3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Peng, X.; Jiang, L.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, J.; Yu, H. Terephthalate Acid Decorated TiO2 for Visible Light Driven Photocatalysis Mediated via Ligand-to-Metal Charge Transfer (LMCT). Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2020, 603, 125188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krylov, I.B.; Lopat’eva, E.R.; Subbotina, I.R.; Nikishin, G.I.; Yu, B.; Terent’ev, A.O. Mixed Hetero-/Homogeneous TiO2/N-Hydroxyimide Photocatalysis in Visible-Light-Induced Controllable Benzylic Oxidation by Molecular Oxygen. Chin. J. Catal. 2021, 42, 1700–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopat’eva, E.R.; Krylov, I.B.; Segida, O.O.; Merkulova, V.M.; Ilovaisky, A.I.; Terent’ev, A.O. Heterogeneous Photocatalysis as a Potent Tool for Organic Synthesis: Cross-Dehydrogenative C–C Coupling of N-Heterocycles with Ethers Employing TiO2/N-Hydroxyphthalimide System under Visible Light. Molecules 2023, 28, 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilisz, I.; Föglein, K.; Dombi, A. The Photochemical Behavior of Hydrogen Peroxide in near UV-Irradiated Aqueous TiO2 Suspensions. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 1998, 135, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, T.; Masaki, Y.; Hirayama, S.; Matsumura, M. TiO2-Photocatalyzed Epoxidation of 1-Decene by H2O2 under Visible Light. J. Catal. 2001, 204, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.; Choy, W.K.; So, T.Y. The Effect of Solution pH and Peroxide in the TiO2-Induced Photocatalysis of Chlorinated Aniline. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 141, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuzawa, S.; Tanaka, J.; Sato, S.; Ibusuki, T. Photocatalytic Oxidation of Dibenzothiophenes in Acetonitrile Using TiO2: Effect of Hydrogen Peroxide and Ultrasound Irradiation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2002, 149, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.C.; Chu, W. The Hydrogen Peroxide-Assisted Photocatalytic Degradation of Alachlor in TiO2 Suspensions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 2310–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adán, C.; Carbajo, J.; Bahamonde, A.; Martínez-Arias, A. Phenol Photodegradation with Oxygen and Hydrogen Peroxide over TiO2 and Fe-Doped TiO2. Catal. Today 2009, 14, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.; Wong, C.C. The Photocatalytic Degradation of Dicamba in TiO2 Suspensions with the Help of Hydrogen Peroxide by Different near UV Irradiations. Water Res. 2004, 38, 1037–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinato, K.; Suttiponparnit, K.; Panpa, W.; Jinawath, S.; Kashima, D. Photocatalytic Activity of TiO 2 Coated Porous Silica Beads on Degradation of Cumene Hydroperoxide. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2018, 15, 1542–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, R.; Warkad, I.R.; Arulkumar, S.; Parthiban, S.; Darji, H.R.; Naushad, M.; Kadam, R.G.; Gawande, M.B. Facile Synthesis of Nanostructured TiO2-SiO2 Powder for Selective Photocatalytic Oxidation of Alcohols to Carbonyl Compounds. Mol. Catal. 2022, 530, 112566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, Y.; Ma, X.; Liu, P.; Gu, C.; Dai, B. Metal-Free Oxidation of Secondary Benzylic Alcohols Using Aqueous TBHP. Synth. Commun. 2016, 46, 1747–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Zheng, T.; Yu, Y.; Xu, K. TBHP-Promoted Direct Oxidation Reaction of Benzylic C sp3–H Bonds to Ketones. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 15176–15180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawadiak, J.; Gilner, D.; Mazurkiewicz, R.; Orlinska, B. Copper Salt–Crown Ether Systems as Catalysts for the Oxidation of Isopropyl Arenes with Tertiary Hydroperoxides to Peroxides. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2001, 205, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, M.B.; Moorthy, S.; Patil, S.; Bisht, G.S.; Mohamed, H.; Basu, S.; Gnanaprakasam, B. Iron-Catalyzed Batch/Continuous Flow C–H Functionalization Module for the Synthesis of Anticancer Peroxides. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 1358–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, D.-L.; Cheng, L.; Yue, T.; Wu, H.-R.; Feng, W.-C.; Wang, D.; Liu, L. Cobalt-Catalyzed Peroxidation of 2-Oxindoles with Hydroperoxides. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 5337–5344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bityukov, O.V.; Vil’, V.A.; Sazonov, G.K.; Kirillov, A.S.; Lukashin, N.V.; Nikishin, G.I.; Terent’ev, A.O. Kharasch Reaction: Cu-Catalyzed and Non-Kharasch Metal-Free Peroxidation of Barbituric Acids. Tetrahedron Lett. 2019, 60, 920–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klare, H.F.T.; Goldberg, A.F.G.; Duquette, D.C.; Stoltz, B.M. Oxidative Fragmentations and Skeletal Rearrangements of Oxindole Derivatives. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 988–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ubale, A.S.; Chaudhari, M.B.; Shaikh, M.A.; Gnanaprakasam, B. Manganese-Catalyzed Synthesis of Quaternary Peroxides: Application in Catalytic Deperoxidation and Rearrangement Reactions. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 10488–10503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, W.-W.; Zhu, W.-M.; Gao, Z.; Liang, H.; Wei, W.-T. C(sp3)–H Peroxidation of 3-Substituted Indolin-2-Ones under Metal-Free Conditions. Synlett 2018, 29, 663–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Bao, X.; Wang, J.; Huo, C. Peroxidation of 3,4-Dihydro-1,4-Benzoxazin-2-Ones. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 3895–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, M.B.; Mohanta, N.; Pandey, A.M.; Vandana, M.; Karmodiya, K.; Gnanaprakasam, B. Peroxidation of 2-Oxindole and Barbituric Acid Derivatives under Batch and Continuous Flow Using an Eco-Friendly Ethyl Acetate Solvent. React. Chem. Eng. 2019, 4, 1277–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minisci, F.; Fontana, F.; Araneo, S.; Recupero, F. New Syntheses of Mixed Peroxides under Gif–Barton Oxidation of Alkylbenzenes, Conjugated Alkenes and Alkanes; a Free-Radical Mechanism. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1994, 16, 1823–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vil’, V.A.; Barsegyan, Y.A.; Kuhn, L.; Terent’ev, A.O.; Alabugin, I.V. Creating, Preserving, and Directing Carboxylate Radicals in Ni-Catalyzed C(sp3)–H Acyloxylation of Ethers, Ketones, and Alkanes with Diacyl Peroxides. Organometallics 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murahashi, S.-I.; Naota, T.; Kuwabara, T. Ruthenium-Catalyzed Oxidation of Nitriles with Tert -Butyl Hydroperoxide. Synlett 1989, 1989, 62–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzina, S.I.; Bol’shakov, A.I.; Kulikov, A.V.; Mikhailov, A.I. Low-Temperature Photolysis of Benzoyl Peroxide. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. 2020, 94, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.P.; Vederas, J.C. Synthesis of β-Cyclopropylalanines by Photolysis of Diacyl Peroxides. Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 4669–4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spantulescu, M.D.; Boudreau, M.A.; Vederas, J.C. Retention of Configuration in Photolytic Decarboxylation of Peresters to Form Chiral Acetals and Ethers. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 645–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cookson, P.G.; Davies, A.G.; Roberts, B.P.; Tse, M.-W. Photolysis of Di-t-Butyl Peroxide under Acid Conditions. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1976, 22, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, D.; Majumdar, B.; Deori, B.; Jain, S.; Sarma, T.K. Photoinduced Enhanced Decomposition of TBHP: A Convenient and Greener Pathway for Aqueous Domino Synthesis of Quinazolinones and Quinoxalines. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 11902–11910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.A.N.; Nguyen, L.H.; Nguyen, Q.N.B.; Nguyen, H.T.; Nguyen, K.Q.; Tran, P.H. Straightforward Synthesis of Benzoxazoles and Benzothiazoles via Photocatalytic Radical Cyclization of 2-Substituted Anilines with Aldehydes. Catal. Commun. 2020, 145, 106120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, W.-Z.; Zhang, W.-J.; Li, C.-Y.; Shao, L.-H.; Liu, Q.-P.; Feng, S.-X.; Geng, Y.; Chen, X.-L.; Qu, L.-B. Photoexcited Sulfenylation of C(sp3)–H Bonds in Amides Using Thiosulfonates. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2022, 20, 3902–3906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katta, N.; Ojha, M.; Murugan, A.; Arepally, S.; Sharada, D.S. Visible Light-Mediated Photocatalytic Oxidative Cleavage of Activated Alkynes via Hydroamination: A Direct Approach to Oxamates. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 12599–12603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, W.-Z.; Zhang, W.-J.; Li, Z.-J.; He, Y.-H.; Feng, S.-X.; Geng, Y.; Chen, X.-L.; Qu, L.-B. Visible-Light-Promoted Synthesis of Secondary and Tertiary Thiocarbamates from Thiosulfonates and N -Substituted Formamides. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2021, 19, 8701–8705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhu, S.; Koenigs, R.M. Photocatalytic 1,2-Oxo-Alkylation Reaction of Styrenes with Diazoacetates. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 7526–7529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Chen, L.; Wang, T.; Xiong, F. Synthesis of Coumarin 3-aldehyde Derivatives via Photocatalytic Cascade Radical Cyclization-Hydrolysis. ChemistrySelect 2022, 7, e202200822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, P.; Wang, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Duan, L.; Li, W.; Sarina, S.; et al. Visible-Light Photocatalytic Selective Oxidation of C(sp3)–H Bonds by Anion–Cation Dual-Metal-Site Nanoscale Localized Carbon Nitride. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2021, 11, 4429–4438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Jie, G.; Liu, J.; Fu, Y.; Ma, R.; Lu, X.; Zhang, F.; Zhu, W.; Fan, M. Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalytic Selective Oxidation of Amines and Sulfides over a Vanadium Metal–Organic Framework. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2022, 6, 5261–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Photocatalytic Oxidative Esterification of Alcohols with N-Hydroxyimides on N-Doped Titania. Synfacts 2019, 15, 1411. [CrossRef]

- Shafiq, N.; Arshad, U.; Zarren, G.; Parveen, S.; Javed, I.; Ashraf, A. A Comprehensive Review: Bio-Potential of Barbituric Acid and Its Analogues. Curr. Org. Chem. 2020, 24, 129–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmachari, G.; Bhowmick, A.; Karmakar, I. Catalyst- and Additive-Free C(sp3)–H Functionalization of (Thio)Barbituric Acids via C-5 Dehydrogenative Aza-Coupling Under Ambient Conditions. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 30051–30063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krylov, I.B.; Paveliev, S.A.; Budnikov, A.S.; Segida, O.O.; Merkulova, V.M.; Vil’, V.A.; Nikishin, G.I.; Terent’ev, A.O. Hidden Reactivity of Barbituric and Meldrum’s Acids: Atom-Efficient Free-Radical C–O Coupling with N-Hydroxy Compounds. Synthesis 2022, 54, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bityukov, O.V.; Kirillov, A.S.; Serdyuchenko, P.Y.; Kuznetsova, M.A.; Demidova, V.N.; Vil’, V.A.; Terent’ev, A.O. Electrochemical Thiocyanation of Barbituric Acids. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2022, 20, 3629–3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.T.; Haque, M.A.; Igarashi, H.; Nishino, H. Mn(III)-Initiated Facile Oxygenation of Heterocyclic 1,3-Dicarbonyl Compounds. Molecules 2011, 16, 9562–9581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, G.A. Deuterium-Isotope Effects in the Autoxidation of Aralkyl Hydrocarbons. Mechanism of the Interaction of PEroxy Radicals 1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1957, 79, 3871–3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiatt, R.; Clipsham, J.; Visser, T. The induced decomposition of tert -butyl hydroperoxide. Can. J. Chem. 1964, 42, 2754–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, H.; Bickel, A.F. Decomposition of Organic Hydroperoxides. Part 4—The Mechanism of the Decomposition of Tert-Butyl Hydroperoxide Catalyzed by Cupric Phenanthroline Acetate. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1961, 57, 1325–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiatt, R.R.; Mill, T.; Mayo, F.R. Homolytic Decompositions of Hydroperoxides. I. Summary and Implications for Autoxidation. J. Org. Chem. 1968, 33, 1416–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Gu, K.; Bao, Z.; Xing, H.; Yang, Q.; Ren, Q. Mechanistic Studies of Thiourea-Catalyzed Cross-Dehydrogenative C-P and C-C Coupling Reactions and Their Further Applications. Tetrahedron 2017, 73, 3118–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer-Chaput, B.; Klussmann, M. Brønsted Acid Catalyzed C-H Functionalization of N -Protected Tetrahydroisoquinolines via Intermediate Peroxides: C-H Functionalization of N -Protected Tetrahydroisoquinolines. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 2013, 666–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Wang, Q.; Yan, C.; Dong, J.; Song, H.; Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liu, X.; Song, H. Merging Photoredox with Brønsted Acid Catalysis: The Cross-Dehydrogenative C−O Coupling for Sp3 C−H Bond Peroxidation. Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 23, 10871–10877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansode, A.H.; Suryavanshi, G. Visible-Light-Induced Controlled Oxidation of N-Substituted 1,2,3,4-Tetrahydroisoquinolines for the Synthesis of 3,4-Dihydroisoquinolin-1(2H)-ones and Isoquinolin-1(2H)-ones. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2021, 363, 1390–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll, S.; Schweiger, A. EasySpin, a Comprehensive Software Package for Spectral Simulation and Analysis in EPR. J. Magn. Reson. 2006, 178, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, F.; McLaughlin, M.; Liu, Y.; Mangion, I.; Tschaen, D.M.; Xu, Y. A Mild Cu(I)-Catalyzed Oxidative Aromatization of Indolines to Indoles. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 10009–10015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyama, R.; Abe, M. Reactivity and Product Analysis of a Pair of Cumyloxyl and Tert -Butoxyl Radicals Generated in Photolysis of Tert -Butyl Cumyl Peroxide. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 8627–8638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dikalov, S.I.; Mason, R.P. Reassignment of Organic Peroxyl Radical Adducts. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 27, 864–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, S.; Xue, S.; Peng, S.; Jing, M.; Qian, X.; Shen, X.; Li, T.; Wang, Y. Synthesis of Graphitic Carbon Nitride at Different Thermal-Pyrolysis Temperature of Urea and It Application in Lithium–Sulfur Batteries. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2018, 29, 17921–17930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Ma, S.; He, K.; Xu, Y.; Fang, Y.; Liu, W.; Gao, Q. Enhanced Visible-Light H2 Evolution of g-C3N4 Photocatalysts via the Synergetic Effect of Amorphous NiS and Cheap Metal-Free Carbon Black Nanoparticles as Co-Catalysts. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 358, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terent’ev, A.O.; Sharipov, M.Y.; Krylov, I.B.; Gaidarenko, D.V.; Nikishin, G.I. Manganese Triacetate as an Efficient Catalyst for Bisperoxidation of Styrenes. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 1439–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, M.; Liu, R.; Yu, W.; Chang, J. Iodine-Catalyzed α-Hydroxylation of β-Dicarbonyl Compounds. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2023, 12, e202200639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhineshkumar, J.; Lamani, M.; Alagiri, K.; Prabhu, K.R. A Versatile C–H Functionalization of Tetrahydroisoquinolines Catalyzed by Iodine at Aerobic Conditions. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 1092–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Entry | Peroxide | Conversion, % | Yield a 2, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | t-BuOOH | 81 | 58 |

| 2 b | t-BuOOH | 0 | nd |

| 3 c | PhC(OOH)(CH3)2 (80%) | 63 | 31 |

| 4 | BzOOBz (75%) | <5 | trace |

| 5 | mCPBA (75%) | 40 | 40 |

| 6 | t-BuOOt-Bu | <5 | nd |

| № | Changes to the General Conditions | Conversion, % | Yield a 9a, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | none | 100 | 54 |

| 2 | no light | 0 | nd |

| 3 | no TiO2 | 0 | nd |

| 4 | air atmosphere | 100 | 37 |

| 5 | reaction time 1 h | 79 | 38 |

| 6 | reaction time 2 h | 94 | 40 |

| 7 | reaction time 8 h | 100 | 55 |

| 8 | 1 equiv. of t-BuOOH | 70 | 24 |

| 9 | 2 equiv. of t-BuOOH | 81 | 35 |

| 10 | 6 equiv. of t-BuOOH | 100 | 50 |

| 11 | 5 mg of TiO2 | 84 | 31 |

| 12 | 20 mg of TiO2 | 100 | 46 |

| 13 | DMSO as a solvent | 59 | 7 |

| 14 | DMF as a solvent | 100 | 14 |

| 15 | AcOH as a solvent | 100 | 32 |

| 16 | DCE as a solvent | 78 | 29 |

| 17 | g-C3N4 instead of TiO2 | 56 | 23 |

| 18 | scaled up to 1 mmol of 8a | 100 | 56 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lopat’eva, E.R.; Krylov, I.B.; Terent’ev, A.O. t-BuOOH/TiO2 Photocatalytic System as a Convenient Peroxyl Radical Source at Room Temperature under Visible Light and Its Application for the CH-Peroxidation of Barbituric Acids. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1306. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal13091306

Lopat’eva ER, Krylov IB, Terent’ev AO. t-BuOOH/TiO2 Photocatalytic System as a Convenient Peroxyl Radical Source at Room Temperature under Visible Light and Its Application for the CH-Peroxidation of Barbituric Acids. Catalysts. 2023; 13(9):1306. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal13091306

Chicago/Turabian StyleLopat’eva, Elena R., Igor B. Krylov, and Alexander O. Terent’ev. 2023. "t-BuOOH/TiO2 Photocatalytic System as a Convenient Peroxyl Radical Source at Room Temperature under Visible Light and Its Application for the CH-Peroxidation of Barbituric Acids" Catalysts 13, no. 9: 1306. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal13091306