Gut–CNS-Axis as Possibility to Modulate Inflammatory Disease Activity—Implications for Multiple Sclerosis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

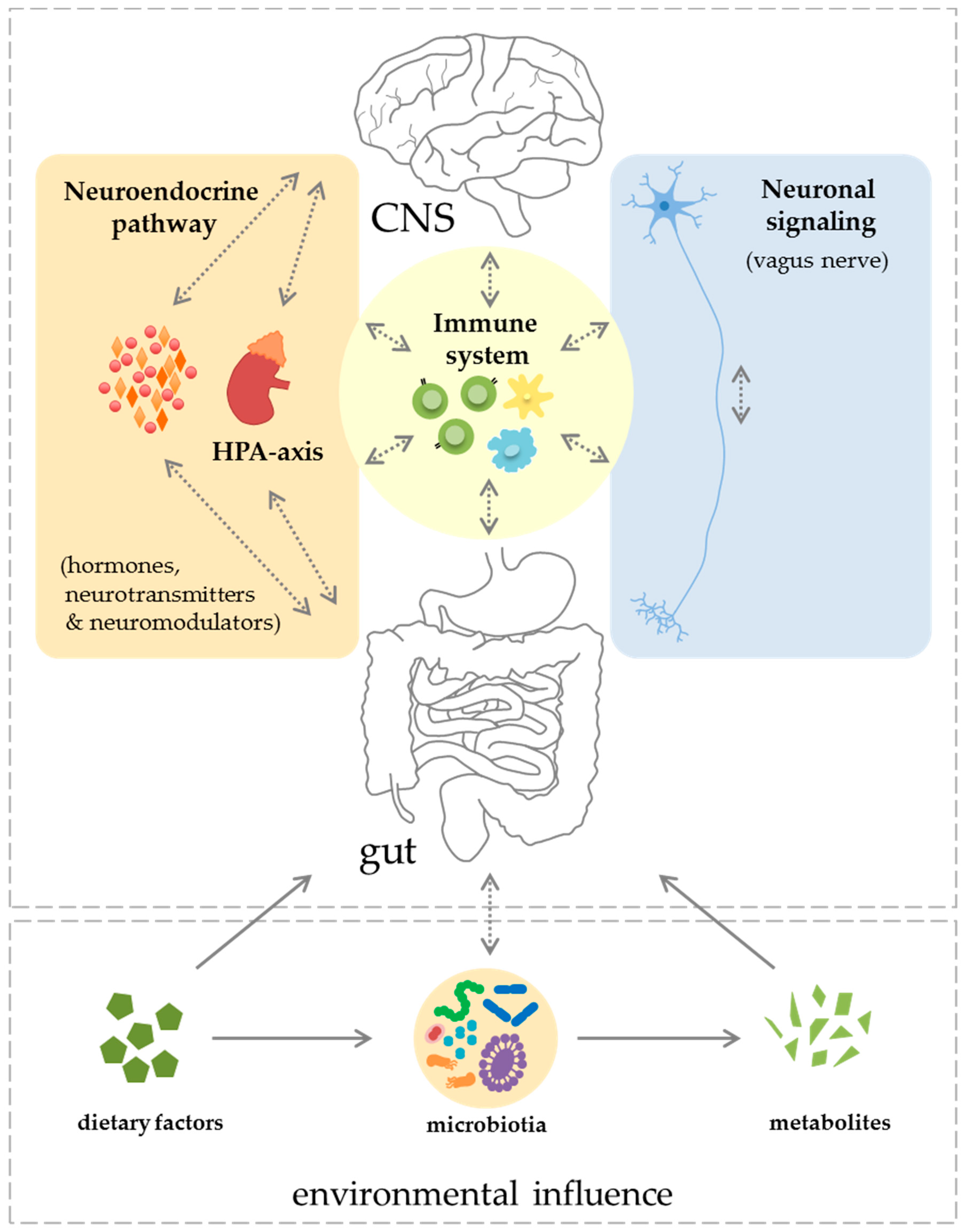

2. Components of the Gut–CNS-Axis

2.1. Neuronal Signaling and Neuroendocrine Component

2.2. Immune System

2.2.1. Innate Immune System

Myeloid Cells

Natural Killer T Cells

Innate Lymphoid Cells

Mucosal-Associated Invariant T Cells

2.2.2. Adaptive Immune System

Pro-Inflammatory Effector T Cells

Anti-Inflammatory T Regulatory Cells

B Cells

3. The Role of the Gut–CNS-Axis in Multiple Sclerosis

3.1. Pre-Clinical Studies

3.2. Clinical Studies

4. Conclusions and Further Perspectives

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AID | Activation-induced cytidine deaminase |

| ANS | Autonomic nerve system |

| CD | Cluster of differentiation |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CXCL16 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 16 |

| EAE | Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis |

| ENS | Enteric nervous system |

| FoxP3 | Forkhead box P3 |

| GABA | Gamma-aminobutyric acid |

| GALT | Gut-associated lymphatic tissue |

| HPA axis | Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis |

| IBD | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| IFN | Interferon |

| IgA | Immunoglobulin A |

| IL | Interleukin |

| ILC | Innate immune lymphoid cell |

| MAMP | Microbial-associated molecular pattern |

| MS | Multiple sclerosis |

| NK cell | Natural killer cell |

| NMO | Neuromyelitis optica |

| PD-1 | Programmed cell death 1 |

| PSA | Polysaccharide A |

| RORγt | Retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor-γt |

| SCFA | Short-chain fatty acids |

| SFB | Segmented filamentous bacteria |

| TGFβ1 | Transforming growth factor β1 |

| Th1 cell | T helper cell type 1 |

| Th17 cell | T helper cell type 17 |

| TLR | Toll-like receptors |

| TNFα | Tumor necrosis factor α |

| Treg cell | Regulatory T cell |

References

- Allison, D.B.; Bassaganya-Riera, J.; Burlingame, B.; Brown, A.W.; le Coutre, J.; Dickson, S.L.; van Eden, W.; Garssen, J.; Hontecillas, R.; Khoo, C.S.H.; et al. Goals in nutrition science. Front. Nutr. 2015, 2, 2015–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dendrou, C.A.; Fugger, L.; Friese, M.A. Immunopathology of multiple sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemmer, B.; Archelos, J.J.; Hartung, H.P. New concepts in the immunopathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002, 3, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvetti, M.; Ristori, G.; Bomprezzi, R.; Pozzilli, P.; Leslie, R.D.G. Twins: Mirrors of the immune system. Immunol. Today 2000, 21, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willer, C.J.; Dyment, D.A.; Risch, N.J.; Sadovnick, A.D.; Ebers, G.C. Twin concordance and sibling recurrence rates in multiple sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 12877–12882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemmer, B.; Kerschensteiner, M.; Korn, T. Role of the innate and adaptive immune responses in the course of multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 406–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hucke, S.; Eschborn, M.; Liebmann, M.; Herold, M.; Freise, N.; Engbers, A.; Ehling, P.; Meuth, S.G.; Roth, J.; Kuhlmann, T.; et al. Sodium chloride promotes pro-inflammatory macrophage polarization thereby aggravating CNS autoimmunity. J. Autoimmun. 2016, 67, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinewietfeld, M.; Manzel, A.; Titze, J.; Kvakan, H.; Yosef, N.; Linker, R.A.; Muller, D.N.; Hafler, D.A. Sodium chloride drives autoimmune disease by the induction of pathogenic TH17 cells. Nature 2013, 496, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Yosef, N.; Thalhamer, T.; Zhu, C.; Xiao, S.; Kishi, Y.; Regev, A.; Kuchroo, V.K. Induction of pathogenic TH17 cells by inducible salt-sensing kinase SGK1. Nature 2013, 496, 513–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besusso, D.; Saul, L.; Leech, M.D.; O’Connor, R.A.; MacDonald, A.S.; Anderton, S.M.; Mellanby, R.J. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3-conditioned CD11c+ dendritic cells are effective initiators of CNS autoimmune disease. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, R.M.; Byrne, S.N.; Correale, J.; Ilschner, S.; Hart, P.H. Ultraviolet radiation, vitamin D and multiple sclerosis. Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 2015, 5, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aktas, O.; Prozorovski, T.; Smorodchenko, A.; Savaskan, N.E.; Lauster, R.; Kloetzel, P.M.; Infante-Duarte, C.; Brocke, S.; Zipp, F. Green tea epigallocatechin-3-gallate mediates T cellular NF-B inhibition and exerts neuroprotection in autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol. 2004, 173, 5794–5800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unoda, K.; Doi, Y.; Nakajima, H.; Yamane, K.; Hosokawa, T.; Ishida, S.; Kimura, F.; Hanafusa, T. Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) induces peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Neuroimmunol. 2013, 256, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riccio, P.; Rossano, R. Nutrition facts in multiple sclerosis. ASN Neuro 2015, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haghikia, A.; Jörg, S.; Duscha, A.; Berg, J.; Manzel, A.; Waschbisch, A.; Hammer, A.; Lee, D.H.; May, C.; Wilck, N.; et al. Dietary fatty acids directly impact central nervous system autoimmunity via the small intestine. Immunity 2015, 43, 817–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmermans, S.; Bogie, J.F.J.; Vanmierlo, T.; Lütjohann, D.; Stinissen, P.; Hellings, N.; Hendriks, J.J.A. High fat diet exacerbates neuroinflammation in an animal model of multiple sclerosis by activation of the renin angiotensin system. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2013, 9, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, U.P.; Mehrpooya, P.; Marpe, B.; Singh, N.P.; Murphy, E.A.; Mishra, M.K.; Price, B.L.; Nagarkatti, M.; Nagarkatti, P.S. High fat diet influences T cell homeostasis and macrophage phenotype to maintain chronic inflammation. J. Immunol. 2016, 196, 197.15. [Google Scholar]

- Manzel, A.; Muller, D.N.; Hafler, D.A.; Erdman, S.E.; Linker, R.A.; Kleinewietfeld, M. Role of western diet in inflammatory autoimmune diseases. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014, 14, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, S.; Bonavita, S.; Sparaco, M.; Gallo, A.; Tedeschi, G. The role of diet in multiple sclerosis: A review. Nutr. Neurosci. 2017, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, F.; Song, S.; Li, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhou, G.; Li, C. Fish oil, lard and soybean oil differentially shape gut microbiota of middle-aged rats. Nat. Sci. Rep. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamada, N.; Seo, S.U.; Chen, G.Y.; Núñez, G. Role of the Gut microbiota in immunity and inflammatory disease. Nat. Publ. Gr. 2013, 13, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, C.J.; Lynch, D.B.; Murphy, K.; Ulaszewska, M.; Jeffery, I.B.; O’Shea, C.A.; Watkins, C.; Dempsey, E.; Mattivi, F.; Touhy, K.; et al. Evolution of Gut microbiota composition from birth to 24 weeks in the infantmet cohort. Microbiome 2017, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Gut instincts: Microbiota as a key regulator of brain development, ageing and neurodegeneration. J. Physiol. 2016, 2, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korpela, K.; Salonen, A.; Virta, L.J.; Kekkonen, R.A.; Forslund, K.; Bork, P.; de Vos, W.M. Intestinal microbiome is related to lifetime antibiotic use in finnish pre-school children. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamada, N.; Kim, Y.G.; Sham, H.P.; Vallance, B.A.; Puente, J.L.; Martens, E.C.; Nunez, G. Regulated virulence controls the ability of a pathogen to compete with the Gut microbiota. Science 2012, 336, 1325–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Filippo, C.; Cavalieri, D.; Di Paola, M.; Ramazzotti, M.; Poullet, J.B.; Massart, S.; Collini, S.; Pieraccini, G.; Lionetti, P. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 14691–14696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husebye, E.; Hellström, P.M.; Sundler, F.; Chen, J.; Midtvedt, T. Influence of microbial species on small intestinal myoelectric activity and transit in germ-free rats. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2001, 280, G368–G380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, J.R.; Kennedy, P.J.; Cryan, J.F.; Dinan, T.G.; Clarke, G.; Hyland, N.P. Breaking down the barriers: The gut microbiome, intestinal permeability and stress-related psychiatric disorders. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schéle, E.; Grahnemo, L.; Anesten, F.; Hallén, A.; Bäckhed, F.; Jansson, J.O. The Gut microbiota reduces leptin sensitivity and the expression of the obesity-suppressing neuropeptides proglucagon ( GCG ) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor ( BDNF ) in the central nervous system. Endocrinology 2013, 154, 3643–3651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reigstad, C.S.; Salmonson, C.E.; Rainey, J.F.; Szurszewski, J.H.; Linden, D.R.; Sonnenburg, J.L.; Farrugia, G.; Kashyap, P.C. Gut microbes promote colonic serotonin production through an effect of short-chain fatty acids on enterochromaffin cells. FASEB J. 2015, 29, 1395–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, I.; Corwin, E.J.; Brennan, P.A.; Jordan, S.; Murphy, J.R.; Dunlop, A. The infant microbiome: Implications for infant health and neurocognitive development. Nurs. Res. 2016, 65, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cree, B.A.C.; Spencer, C.M.; Varrin-Doyer, M.; Baranzini, S.E.; Zamvil, S.S. Gut microbiome analysis in neuromyelitis optica reveals overabundance of Clostridium perfringens. Ann. Neurol. 2016, 80, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, C.J.K.; Milev, R. The effects of probiotics on depressive symptoms in humans: A systematic review. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2017, 16, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickerson, F.; Severance, E.; Yolken, R. The microbiome, immunity, and schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2017, 62, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Han, Y.; Dy, A.B.C.; Hagerman, R.J. The Gut microbiota and autism spectrum disorders. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klingelhoefer, L.; Reichmann, H. Pathogenesis of parkinson disease—The gut–brain axis and environmental factors. Nat. Publ. Gr. 2015, 11, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pistollato, F.; Sumalla Cano, S.; Elio, I.; Masias Vergara, M.; Giampieri, F.; Battino, M. Role of gut microbiota and nutrients in amyloid formation and pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease. Nutr. Rev. 2016, 74, 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cryan, J.F.; Dinan, T.G. Mind-altering microorganisms: The impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 13, 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furness, J.B.; Kunze, W.A.; Clerc, N. Nutrient tasting and signaling mechanisms in the gut. II. The intestine as a sensory organ: Neural, endocrine, and immune responses. Am. J. Physiol. 1999, 277, G922–G928. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mayer, E.A.; Tillisch, K.; Gupta, A. Gut/brain axis and the microbiota. Nutr. Rev. 2015, 73, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islas Weinstein, L.; Revuelta, A.; Pando, R.H. Catecholamines and acetylcholine are key regulators of the interaction between microbes and the immune system. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2015, 1351, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravo, J.A.; Forsythe, P.; Chew, M.V.; Escaravage, E.; Savignac, H.M.; Dinan, T.G.; Bienenstock, J.; Cryan, J.F. Ingestion of lactobacillus strain regulates emotional behavior and central GABA receptor expression in a mouse via the vagus nerve. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 16050–16055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bercik, P.; Park, A.J.; Sinclair, D.; Khoshdel, A.; Lu, J.; Huang, X.; Deng, Y.; Blennerhassett, P.A.; Fahnestock, M.; Moine, D.; et al. The anxiolytic effect of Bifidobacterium longum NCC3001 involves vagal pathways for gut-brain communication. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2011, 23, 1132–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Kleij, H.; O’Mahony, C.; Shanahan, F.; O’Mahony, L.; Bienenstock, J. Protective effects of Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Bifidobacterium infantis in murine models for colitis do not involve the vagus nerve. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2008, 295, R1131–R1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, T.C.; Olson, C.A.; Hsiao, E.Y. Interactions between the microbiota, immune and nervous systems in health and disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2017, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Written, L.A. Dempsey acetate for memory the tryptophan link coping with stress. Nat. Immunol. IV Immun. IV Nat. Med 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, G.; Grenham, S.; Scully, P.; Fitzgerald, P.; Moloney, R.; Shanahan, F.; Dinan, T.; Cryan, J. The microbiome-gut-brain axis during early life regulates the hippocampal serotonergic system in a sex-dependent manner. Mol. Psychiatry 2012, 18, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephenson, M.; Rowatt, E. The production of acetycholine by a strain of Lactobacillus plantarum. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1947, 1, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, B.B.; Van Benschoten, A.H.; Cimermancic, P.; Donia, M.S.; Zimmermann, M.; Taketani, M.; Ishihara, A.; Kashyap, P.C.; Fraser, J.S.; Fischbach, M.A. Discovery and characterization of gut microbiota decarboxylases that can produce the neurotransmitter tryptamine. Cell Host Microbe 2014, 16, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asano, Y.; Hiramoto, T.; Nishino, R.; Aiba, Y.; Kimura, T.; Yoshihara, K.; Koga, Y.; Sudo, N. Critical role of gut microbiota in the production of biologically active, free catecholamines in the gut lumen of mice. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2012, 303, G1288–G1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, E.; Ross, R.P.; O’Toole, P.W.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; Stanton, C. Aminobutyric acid production by culturable bacteria from the human intestine. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 113, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoverstad, T.; Midtvedt, T. Short-chain fatty acids in germfree mice and rats. J. Nutr. 1986, 116, 1772–1776. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chuang, D.M.; Leng, Y.; Marinova, Z.; Kim, H.J.; Chiu, C.T. Multiple roles of HDAC inhibition in neurodegenerative conditions. Trends Neurosci. 2009, 32, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, P.V.; Hao, L.; Offermanns, S.; Medzhitov, R. The microbial metabolite butyrate regulates intestinal macrophage function via histone deacetylase inhibition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 2247–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remely, M.; Aumueller, E.; Merold, C.; Dworzak, S.; Hippe, B.; Zanner, J.; Pointner, A.; Brath, H.; Haslberger, A.G. Effects of short chain fatty acid producing bacteria on epigenetic regulation of FFAR3 in type 2 diabetes and obesity. Gene 2014, 537, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, A.J.; Collins, J.; Blennerhassett, P.A.; Ghia, J.E.; Verdu, E.F.; Bercik, P.; Collins, S.M. Altered colonic function and microbiota profile in a mouse model of chronic depression. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2013, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ait-Belgnaoui, A.; Durand, H.; Cartier, C.; Chaumaz, G.; Eutamene, H.; Ferrier, L.; Houdeau, E.; Fioramonti, J.; Bueno, L.; Theodorou, V. Prevention of gut leakiness by a probiotic treatment leads to attenuated HPA response to an acute psychological stress in rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2012, 37, 1885–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.M.; Vale, W.W. The role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in neuroendocrine responses to stress. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 8, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bellavance, M.A.; Rivest, S. The HPA–immune axis and the immunomodulatory actions of glucocorticoids in the brain. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, M.T.; Dowd, S.E.; Galley, J.D.; Hufnagle, A.R.; Allen, R.G.; Lyte, M. Exposure to a social stressor alters the structure of the intestinal microbiota: Implications for stressor-induced immunomodulation. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2011, 25, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hueston, C.M.; Deak, T. The inflamed axis: The interaction between stress, hormones, and the expression of inflammatory-related genes within key structures comprising the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Physiol. Behav. 2014, 124, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverman, M.N.; Sternberg, E.M. Glucocorticoid regulation of inflammation and its functional correlates: From HPA axis to glucocorticoid receptor dysfunction. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012, 1261, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gareau, M.G.; Jury, J.; MacQueen, G.; Sherman, P.M.; Perdue, M.H. Probiotic treatment of rat pups normalises corticosterone release and ameliorates colonic dysfunction induced by maternal separation. Gut 2007, 56, 1522–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez de Aguero, M.; Ganal-Vonarburg, S.C.; Fuhrer, T.; Rupp, S.; Uchimura, Y.; Li, H.; Steinert, A.; Heikenwalder, M.; Hapfelmeier, S.; Sauer, U.; et al. The maternal microbiota drives early postnatal innate immune development. Science 2016, 351, 1296–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cebra, J.J. Influences of microbiota on intestinal immune system development. Am. Kournal Clin. Nutr. 1999, 69, 1046–1051. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson, E.; Tremaroli, V.; Lee, Y.S.; Koren, O.; Nookaew, I.; Fricker, A.; Nielsen, J.; Ley, R.E.; Bäckhed, F. Analysis of gut microbial regulation of host gene expression along the length of the gut and regulation of gut microbial ecology through MyD88. Gut 2012, 61, 1124–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, X.C.; Kabakchiev, B.; Waldron, L.; Tyler, A.D.; Tickle, T.L.; Milgrom, R.; Stempak, J.M.; Gevers, D.; Xavier, R.J.; Silverberg, M.S.; et al. Associations between host gene expression, the mucosal microbiome, and clinical outcome in the pelvic pouch of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Genome Biol. 2015, 16, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavelle, E.C.; Murphy, C.; O’Neill, L.A.J.; Creagh, E.M. The role of TLRs, NLRs, and RLRs in mucosal innate immunity and homeostasis. Mucosal Immunol. 2010, 3, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, C.J.; Colgan, S.P.; Frank, D.N. Of microbes and meals: The health consequences of dietary endotoxemia. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2012, 27, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemente, J.C.; Ursell, L.K.; Parfrey, L.W.; Knight, R. The impact of the gut microbiota on human health: An integrative view. Cell 2012, 148, 1258–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crack, P.J.; Bray, P.J. Toll-like receptors in the brain and their potential roles in neuropathology. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2007, 85, 476–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenchley, J.M.; Douek, D.C. Microbial translocation across the GI tract. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2012, 30, 149–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Begum-Haque, S.; Telesford, K.M.; Ochoa-Repáraz, J.; Christy, M.; Kasper, E.J.; Kasper, D.L.; Robson, S.C.; Kasper, L.H. A commensal bacterial product elicits and modulates migratory capacity of CD39+ CD4 T regulatory subsets in the suppression of neuroinflammation. Gut Microbes 2014, 5, 552–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telesford, K.M.; Yan, W.; Ochoa-Reparaz, J.; Pant, A.; Kircher, C.; Christy, M.A.; Begum-Haque, S.; Kasper, D.L.; Kasper, L.H. A commensal symbiotic factor derived from Bacteroides fragilis promotes human CD39+Foxp3+ T cells and Treg function. Gut Microbes 2015, 6, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochoa-Repáraz, J.; Mielcarz, D.W.; Wang, Y.; Begum-Haque, S.; Dasgupta, S.; Kasper, D.L.; Kasper, L.H. A polysaccharide from the human commensal Bacteroides fragilis protects against CNS demyelinating disease. Mucosal Immunol. 2010, 3, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochoa-Repáraz, J.; Mielcarz, D.W.; Ditrio, L.E.; Burroughs, A.R.; Begum-Haque, S.; Dasgupta, S.; Kasper, D.L.; Kasper, L.H. Central nervous system demyelinating disease protection by the human commensal Bacteroides fragilis depends on polysaccharide A expression. J. Immunol. 2010, 185, 4101–4108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochoa-Repáraz, J.; Mielcarz, D.W.; Haque-Begum, S.; Kasper, L.H. Induction of a regulatory B cell population in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis by alteration of the gut commensal microflora. Gut Microbes 2010, 1, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ransohoff, R.M.; Engelhardt, B. The anatomical and cellular basis of immune surveillance in the central nervous system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2012, 12, 623–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erny, D.; Hrabě de Angelis, A.L.; Jaitin, D.; Wieghofer, P.; Staszewski, O.; David, E.; Keren-Shaul, H.; Mahlakoiv, T.; Jakobshagen, K.; Buch, T.; et al. Host microbiota constantly control maturation and function of microglia in the CNS. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothhammer, V.; Ivan, D.M.; Bunse, L.; Takenaka, M.C.; Kenison, J.E.; Mayo, L.; Chao, C.C.; Patel, B.; Yan, R.; Blain, M.; et al. Type I interferons and microbial metabolites of tryptophan modulate astrocyte activity and CNS inflammation via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nat. Med. 2016, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janeway, C.A. Approaching the asymptote? Evolution and revolution in immunology. In Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA, 1989; Volume 54, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Franchi, L.; Kamada, N.; Nakamura, Y.; Burberry, A.; Kuffa, P.; Suzuki, S.; Shaw, M.H.; Kim, Y.G.; Núñez, G. NLRC4-driven production of IL-1β discriminates between pathogenic and commensal bacteria and promotes host intestinal defense. Nat. Immunol. 2012, 13, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganal, S.C.; Sanos, S.L.; Kallfass, C.; Oberle, K.; Johner, C.; Kirschning, C.; Lienenklaus, S.; Weiss, S.; Staeheli, P.; Aichele, P.; et al. Priming of natural killer cells by nonmucosal mononuclear phagocytes requires instructive signals from commensal microbiota. Immunity 2012, 37, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olszak, T.; An, D.; Zeissig, S.; Vera, M.P.; Richter, J.; Franke, A.; Glickman, J.N.; Siebert, R.; Baron, R.M.; Kasper, D.L.; et al. Microbial exposure during early life has persistent effects on natural killer T cell function. Science 2012, 336, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, M.; Thaiss, C.A.; Elinav, E. Metagenomic cross-talk: The regulatory interplay between immunogenomics and the microbiome. Genome Med. 2015, 7, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satoh-Takayama, N.; Vosshenrich, C.A.J.; Lesjean-Pottier, S.; Sawa, S.; Lochner, M.; Rattis, F.; Mention, J.J.; Thiam, K.; Cerf-Bensussan, N.; Mandelboim, O.; et al. Microbial flora drives interleukin 22 production in intestinal NKp46+ cells that provide innate mucosal immune defense. Immunity 2008, 29, 958–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonnenberg, G.F.; Monticelli, L.A.; Alenghat, T.; Fung, T.C.; Hutnick, N.A.; Kunisawa, J.; Shibata, N.; Grunberg, S.; Sinha, R.; Zahm, A.M.; et al. Innate lymphoid cells promote anatomical containment of lymphoid-resident commensal bacteria. Science 2012, 336, 1321–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawa, S.; Lochner, M.; Satoh-Takayama, N.; Dulauroy, S.; Bérard, M.; Kleinschek, M.; Cua, D.; Di Santo, J.P.; Eberl, G. RORγt+ innate lymphoid cells regulate intestinal homeostasis by integrating negative signals from the symbiotic microbiota. Nat. Immunol. 2011, 12, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treiner, E.; Liblau, R.S. Mucosal-associated invariant T cells in multiple sclerosis: The jury is still out. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salou, M.; Nicol, B.; Garcia, A.; Baron, D.; Michel, L.; Elong-Ngono, A.; Hulin, P.; Nedellec, S.; Jacq-Foucher, M.; Le Frère, F.; et al. Neuropathologic, phenotypic and functional analyses of mucosal associated invariant T cells in multiple sclerosis. Clin. Immunol. 2016, 166, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyazaki, Y.; Miyake, S.; Chiba, A.; Lantz, O.; Yamamura, T. Mucosal-associated invariant T cells regulate Th1 response in multiple sclerosis. Int. Immunol. 2011, 23, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, J.; Leeansyah, E.; Sandberg, J.K. Multiple layers of heterogeneity and subset diversity in human MAIT cell responses to distinct microorganisms and to innate cytokines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E5434–E5443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serriari, N.E.; Eoche, M.; Lamotte, L.; Lion, J.; Fumery, M.; Marcelo, P.; Chatelain, D.; Barre, A.; Nguyen-Khac, E.; Lantz, O.; et al. Innate mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells are activated in inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2014, 176, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Sparks, J.B.; Karyala, S.V.; Settlage, R.; Luo, X.M. Host adaptive immunity alters gut microbiota. Isme J. 2015, 9, 770–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mombaerts, P.; Iacomini, J.; Johnson, R.S.; Herrup, K.; Tonegawa, S.; Papaioannou, V.E. RAG-1-deficient mice have no mature B and T lymphocytes. Cell 1992, 68, 869–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazmanian, S.K.; Cui, H.L.; Tzianabos, A.O.; Kasper, D.L. An immunomodulatory molecule of symbiotic bacteria directs maturation of the host immune system. Cell 2005, 122, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, M.H.; Kamada, N.; Kim, Y.G.; Núñez, G. Microbiota-induced IL-1β, but not IL-6, is critical for the development of steady-state TH17 cells in the intestine. J. Exp. Med. 2012, 209, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanov, I.I.; de Llanos Frutos, R.; Manel, N.; Yoshinaga, K.; Rifkin, D.B.; Sartor, R.B.; Finlay, B.B.; Littman, D.R. Specific microbiota direct the differentiation of IL-17-producing T-Helper cells in the mucosa of the small intestine. Cell Host Microbe 2008, 4, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanov, I.I.; Atarashi, K.; Manel, N.; Brodie, E.L.; Shima, T.; Karaoz, U.; Wei, D.; Goldfarb, K.C.; Santee, C.A.; Lynch, S.V.; et al. Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria. Cell 2009, 139, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atarashi, K.; Nishimura, J.; Shima, T.; Umesaki, Y.; Yamamoto, M.; Onoue, M.; Yagita, H.; Ishii, N.; Evans, R.; Honda, K.; et al. ATP drives lamina propria TH17 cell differentiation. Nature 2008, 455, 808–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sano, T.; Huang, W.; Hall, J.A.; Yang, Y.; Chen, A.; Gavzy, S.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Ziel, J.W.; Miraldi, E.R.; Domingos, A.I.; et al. An IL-23R/IL-22 circuit regulates epithelial serum amyloid a to promote local effector Th17 responses. Cell 2015, 163, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atarashi, K.; Tanoue, T.; Ando, M.; Kamada, N.; Nagano, Y.; Narushima, S.; Suda, W.; Imaoka, A.; Setoyama, H.; Nagamori, T.; et al. Th17 Cell Induction by Adhesion of Microbes to Intestinal Epithelial Cells. Cell 2015, 163, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, S.; Zhao, D.; Cai, C.; Song, D.; Shen, J.; Xu, A.; Qiao, Y.; Ran, Z.; Zheng, Q. Low-dose penicillin exposure in early life decreases Th17 and the susceptibility to DSS colitis in mice through gut microbiota modification. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atarashi, K.; Tanoue, T.; Shima, T.; Imaoka, A.; Kuwahara, T.; Momose, Y.; Cheng, G.; Yamasaki, S.; Saito, T.; Ohba, Y.; et al. Induction of colonic regulatory T cells by indigenous Clostridium species. Science 2011, 331, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geuking, M.B.; Cahenzli, J.; Lawson, M.A.E.; Ng, D.C.K.; Slack, E.; Hapfelmeier, S.; McCoy, K.D.; Macpherson, A.J. Intestinal bacterial colonization induces mutualistic regulatory T cell responses. Immunity 2011, 34, 794–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cording, S.; Fleissner, D.; Heimesaat, M.M.; Bereswill, S.; Loddenkemper, C.; Uematsu, S.; Akira, S.; Hamann, A.; Huehn, J. Commensal microbiota drive proliferation of conventional and Foxp3+ regulatory CD4+ T cells in mesenteric lymph nodes and Peyer’s patches. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. 2013, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Round, J.L.; Mazmanian, S.K. Inducible Foxp3+ regulatory T-cell development by a commensal bacterium of the intestinal microbiota. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. Monit. 2010, 107, 12204–12209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Round, J.L.; Lee, S.M.; Li, J.; Tran, G.; Jabri, B.; Chatila, T.A.; Mazmanian, S.K. The Toll-like receptor 2 pathway establishes colonization by a commensal of the human microbiota. Science 2011, 332, 974–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arpaia, N.; Campbell, C.; Fan, X.; Dikiy, S.; van der Veeken, J.; DeRoos, P.; Liu, H.; Cross, J.R.; Pfeffer, K.; Coffer, P.J.; et al. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature 2013, 504, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furusawa, Y.; Obata, Y.; Fukuda, S.; Endo, T.A.; Nakato, G.; Takahashi, D.; Nakanishi, Y.; Uetake, C.; Kato, K.; Kato, T.; et al. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature 2013, 504, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P.M.; Howitt, M.R.; Panikov, N.; Michaud, M.; Gallini, C.A.; Bohlooly-Y, M.; Glickman, J.N.; Garrett, W.S. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic T reg cell homeostasis. Sciencemag 2013, 341, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawamoto, S.; Maruya, M.; Kato, L.; Suda, W.; Atarashi, K.; Doi, Y.; Tsutsui, Y.; Qin, H.; Honda, K.; Okada, T.; et al. Foxp3+ T cells regulate immunoglobulin a selection and facilitate diversification of bacterial species responsible for immune homeostasis. Immunity 2014, 41, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanoue, T.; Atarashi, K.; Honda, K. Development and maintenance of intestinal regulatory T cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Kim, C.H. Regulation of humoral immunity by gut microbial products. Gut Microbes 2017, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerutti, A. The regulation of IgA class switching. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagarasan, S.; Muramatsu, M.; Suzuki, K.; Nagaoka, H.; Hiai, H.; Honjo, T. Critical roles of activation-induced cytidine deaminase in the homeostasis of gut flora. Science 2002, 298, 1424–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, K.; Meek, B.; Doi, Y.; Muramatsu, M.; Chiba, T.; Honjo, T.; Fagarasan, S. Aberrant expansion of segmented filamentous bacteria in IgA-deficient gut. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 1981–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawamoto, S.; Tran, T.H.; Maruya, M.; Suzuki, K.; Doi, Y.; Tsutsui, Y.; Kato, L.M.; Fagarasan, S. The inhibitory receptor PD-1 regulates IgA selection and bacterial composition in the gut. Science 2012, 336, 485–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berer, K.; Mues, M.; Koutrolos, M.; Rasbi, Z.A.; Boziki, M.; Johner, C.; Wekerle, H.; Krishnamoorthy, G. Commensal microbiota and myelin autoantigen cooperate to trigger autoimmune demyelination—With comments. Nature 2011, 479, 538–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.K.; Menezes, J.S.; Umesaki, Y.; Mazmanian, S.K. Proinflammatory T-cell responses to gut microbiota promote experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 4615–4622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, S.K.; Ito, N.; Mindur, J.E.; Mathay, M.; Dhib-Jalbut, S.; Ito, K. Dysregulation of immune response to enteric bacteria triggers the development of spontaneous experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol. 2016, 196, 54.17. [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa-Repáraz, J.; Mielcarz, D.W.; Ditrio, L.E.; Kasper, L.H. Role of Gut commensal microflora in the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol. 2009, 183, 6041–6050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokote, H.; Miyake, S.; Croxford, J.L.; Oki, S.; Mizusawa, H.; Yamamura, T. NKT cell-dependent amelioration of a mouse model of multiple sclerosis by altering gut flora. Am. J. Pathol. 2008, 173, 1714–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melzer, N.; Meuth, S.G.; Torres-Salazar, D.; Bittner, S.; Zozulya, A.L.; Weidenfeller, C.; Kotsiari, A.; Stangel, M.; Fahlke, C.; Wiendl, H. A β-lactam antibiotic dampens excitotoxic inflammatory CNS damage in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavasani, S.; Dzhambazov, B.; Nouri, M.; Fåk, F.; Buske, S.; Molin, G.; Thorlacius, H.; Alenfall, J.; Jeppsson, B.; Weström, B. A novel probiotic mixture exerts a therapeutic effect on experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mediated by IL-10 producing regulatory T cells. PLoS ONE 2010, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochoa-Repáraz, J.; Rynda, A.; Ascón, M.A.; Yang, X.; Kochetkova, I.; Riccardi, C.; Callis, G.; Trunkle, T.; Pascual, D.W. IL-13 production by regulatory t cells protects against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) independent of auto-antigen. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 954–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nouri, M.; Bredberg, A.; Weström, B.; Lavasani, S. Intestinal barrier dysfunction develops at the onset of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, and can be induced by adoptive transfer of auto-reactive T cells. PLoS ONE 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yacyshyn, B.; Meddings, J.; Sadowski, D.; Bowen-Yacyshyn, M.B. Multiple sclerosis patients have peripheral blood CD45RO+ B cells and increased intestinal permeability. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1996, 41, 2493–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buscarinu, M.C.; Cerasoli, B.; Annibali, V.; Policano, C.; Lionetto, L.; Capi, M.; Mechelli, R.; Romano, S.; Fornasiero, A.; Mattei, G.; et al. Altered intestinal permeability in patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis: A pilot study. Mult. Scler. J. 2017, 23, 442–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Chia, N.; Kalari, K.R.; Yao, J.Z.; Novotna, M.; Soldan, M.M.P.; Luckey, D.H.; Marietta, E.V.; Jeraldo, P.R.; Chen, X.; et al. Multiple sclerosis patients have a distinct gut microbiota compared to healthy controls. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremlett, H.; Fadrosh, D.W.; Faruqi, A.A.; Zhu, F.; Hart, J.; Roalstad, S.; Graves, J.; Lynch, S.; Waubant, E. Gut microbiota in early pediatric multiple sclerosis: A case−control study. Eur. J. Neurol. 2016, 23, 1308–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyake, S.; Kim, S.; Suda, W.; Oshima, K.; Nakamura, M.; Matsuoka, T.; Chihara, N.; Tomita, A.; Sato, W.; Kim, S.W.; et al. Dysbiosis in the gut microbiota of patients with multiple sclerosis, with a striking depletion of species belonging to clostridia XIVa and IV clusters. PLoS ONE 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jangi, S.; Gandhi, R.; Cox, L.M.; Li, N.; von Glehn, F.; Yan, R.; Patel, B.; Mazzola, M.A.; Liu, S.; Glanz, B.L.; et al. Alterations of the human gut microbiome in multiple sclerosis. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantarel, B.L.; Waubant, E.; Chehoud, C.; Kuczynski, J.; DeSantis, T.Z.; Warrington, J.; Venkatesan, A.; Fraser, C.M.; Mowry, E.M. Gut Microbiota in multiple sclerosis. J. Investig. Med. 2015, 63, 729–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashid Rumah, K.; Linden, J.; Fischetti, V.A.; Vartanian, T.; Esteban, F.J. Isolation of clostridium perfringens Type B in an individual at first clinical presentation of multiple sclerosis provides clues for environmental triggers of the disease. PLoS ONE 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrien, M.; Belzer, C.; de Vos, W.M. Akkermansia muciniphila and its role in regulating host functions. Microb. Pathog. 2015, 106, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rumah, K.R.; Vartanian, T.K.; Fischetti, V.A. Oral multiple sclerosis drugs inhibit the in vitro growth of epsilon toxin producing gut bacterium, clostridium perfringens. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wexler, H.M. Bacteroides: The good, the bad, and the nitty-gritty. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2007, 20, 593–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pudlo, N.A.; Martens, E.C. Symbiotic Human Gut Bacteria with Variable Metabolic Priorities for Host Mucosal Glycans. MBio 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremlett, H.; Fadrosh, D.W.; Faruqi, A.A.; Hart, J.; Roalstad, S.; Graves, J.; Lynch, S.; Waubant, E.; Aaen, G.; Belman, A.; et al. Gut microbiota composition and relapse risk in pediatric MS: A pilot study. J. Neurol. Sci. 2016, 363, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokol, H.; Pigneur, B.; Watterlot, L.; Lakhdari, O.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G.; Gratadoux, J.J.; Blugeon, S.; Bridonneau, C.; Furet, J.P.; Corthier, G.; et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 16731–16736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Palma, G.; Nadal, I.; Medina, M.; Donat, E.; Ribes-Koninckx, C.; Calabuig, M.; Sanz, Y. Intestinal dysbiosis and reduced immunoglobulin-coated bacteria associated with coeliac disease in children. BMC Microbiol. 2010, 10, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quévrain, E.; Maubert, M.A.; Michon, C.; Chain, F.; Marquant, R.; Tailhades, J.; Miquel, S.; Carlier, L.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G.; Pigneur, B.; et al. Identification of an anti-inflammatory protein from Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, a commensal bacterium deficient in Crohn’s disease. Gut 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlsson, A.H.; Yakymenko, O.; Olivier, I.; Håkansson, F.; Postma, E.; Keita, Å.V.; Söderholm, J.D. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology Faecalibacterium prausnitzii supernatant improves intestinal barrier function in mice DSS colitis Faecalibacterium prausnitzii supernatant improves intestinal barrier function in mice DSS colitis. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 4810, 1136–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fleck, A.-K.; Schuppan, D.; Wiendl, H.; Klotz, L. Gut–CNS-Axis as Possibility to Modulate Inflammatory Disease Activity—Implications for Multiple Sclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1526. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18071526

Fleck A-K, Schuppan D, Wiendl H, Klotz L. Gut–CNS-Axis as Possibility to Modulate Inflammatory Disease Activity—Implications for Multiple Sclerosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017; 18(7):1526. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18071526

Chicago/Turabian StyleFleck, Ann-Katrin, Detlef Schuppan, Heinz Wiendl, and Luisa Klotz. 2017. "Gut–CNS-Axis as Possibility to Modulate Inflammatory Disease Activity—Implications for Multiple Sclerosis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 18, no. 7: 1526. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18071526