Celf1 Is Required for Formation of Endoderm-Derived Organs in Zebrafish

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

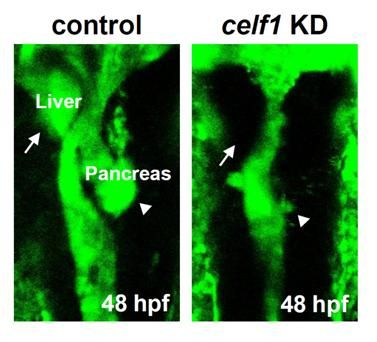

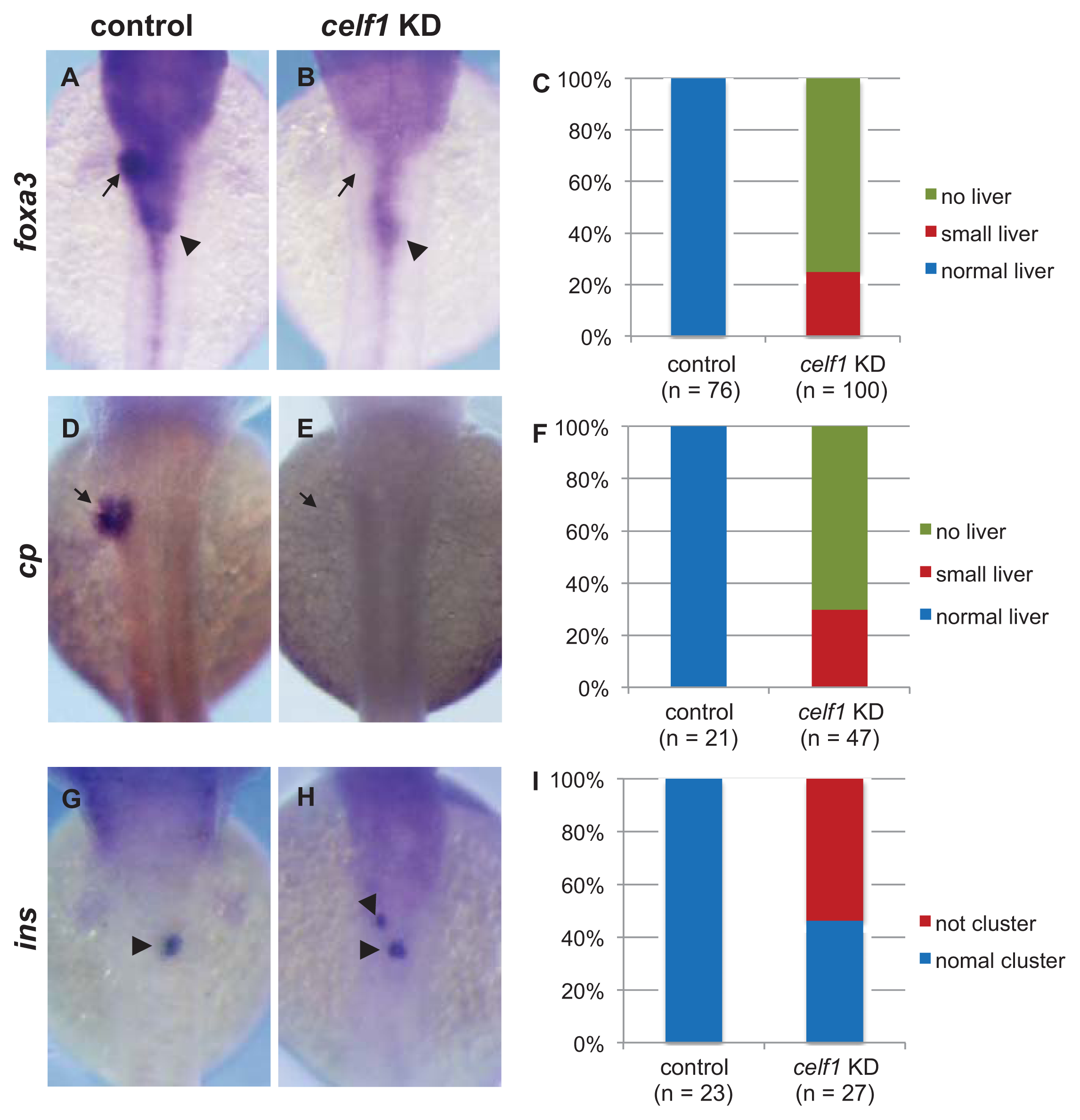

2.1. Celf1 Is Involved in Formation of Endoderm-Derived Organs

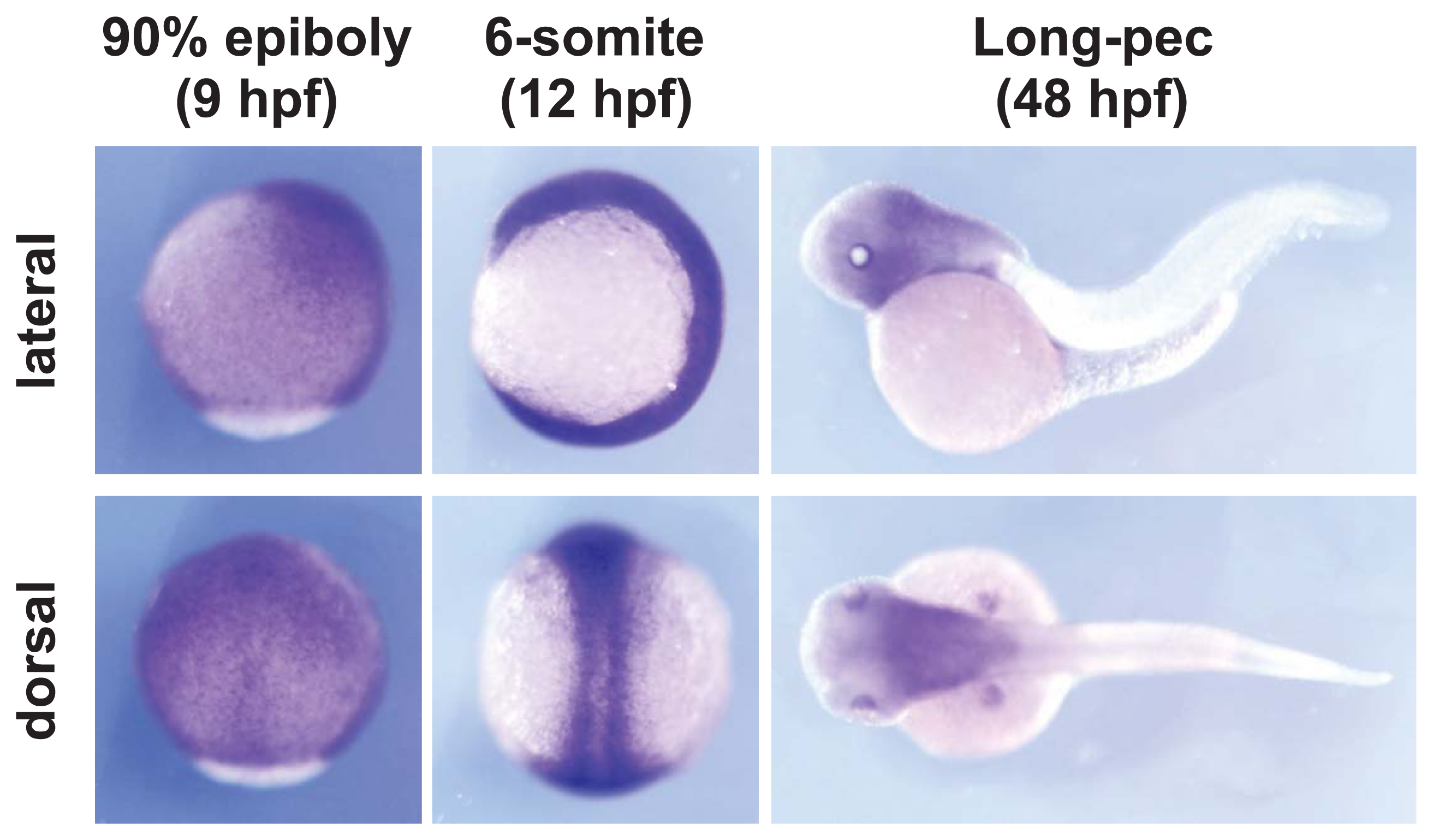

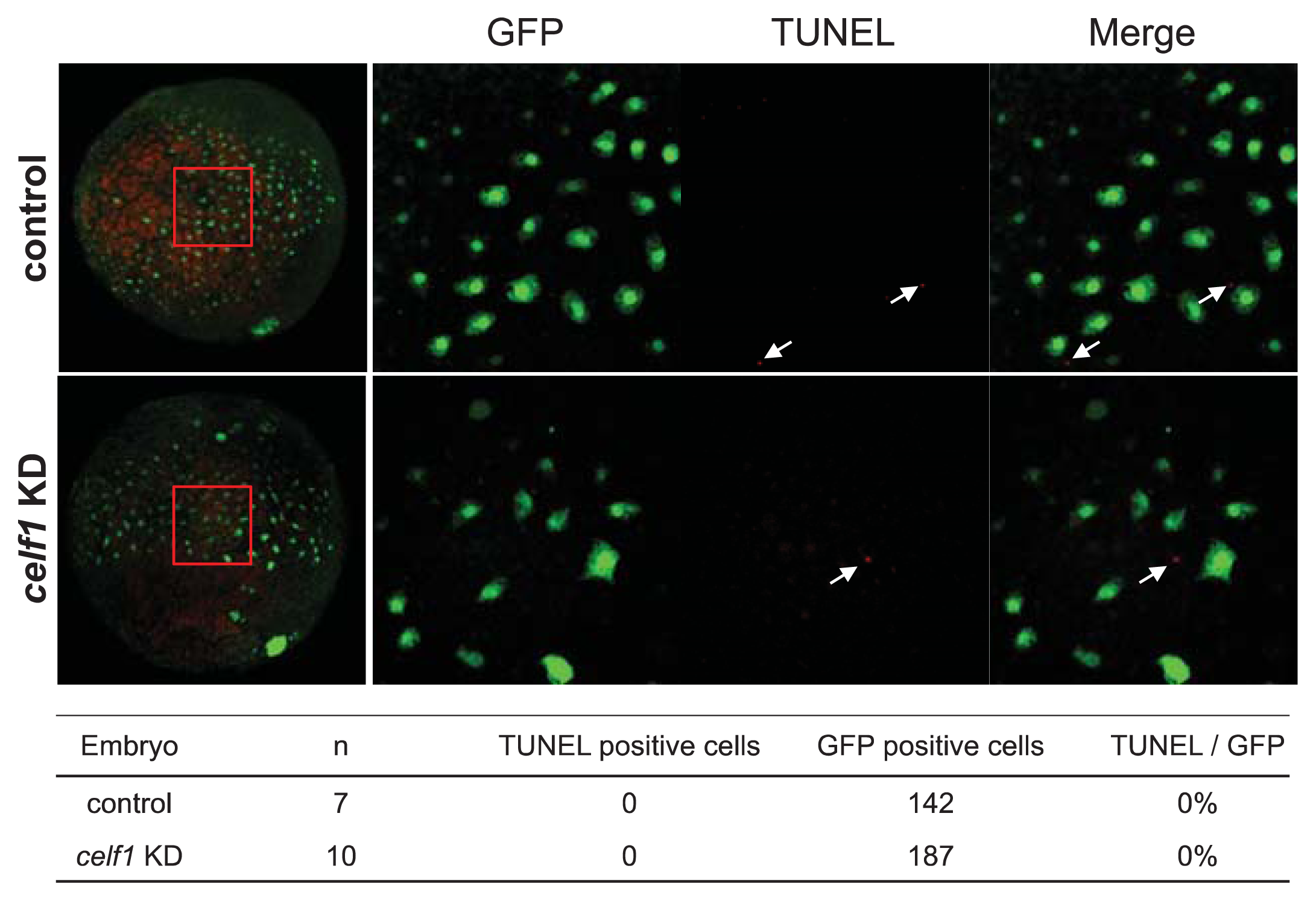

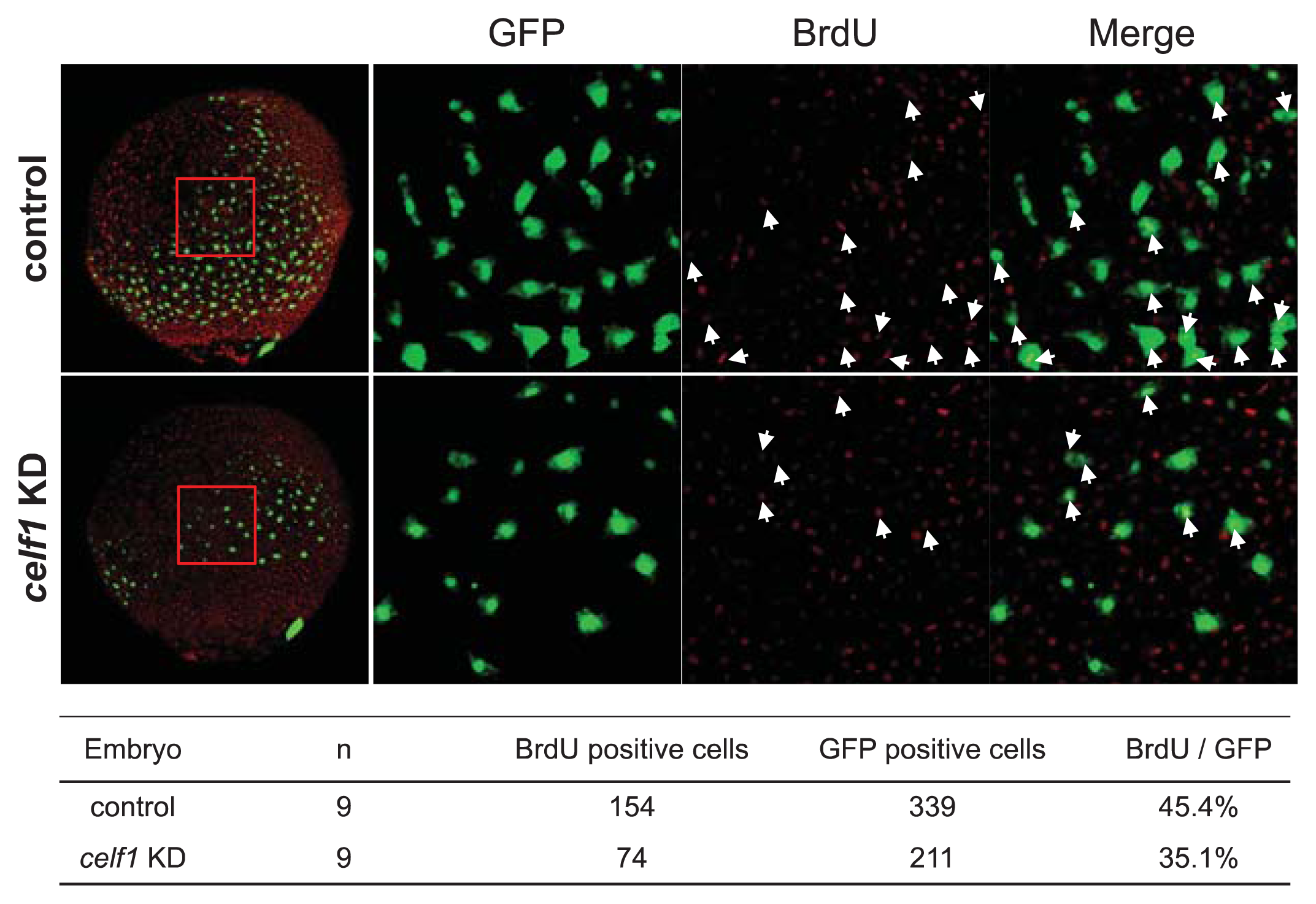

2.2. Celf1 Controls Endoderm Cell Growth during Gastrulation

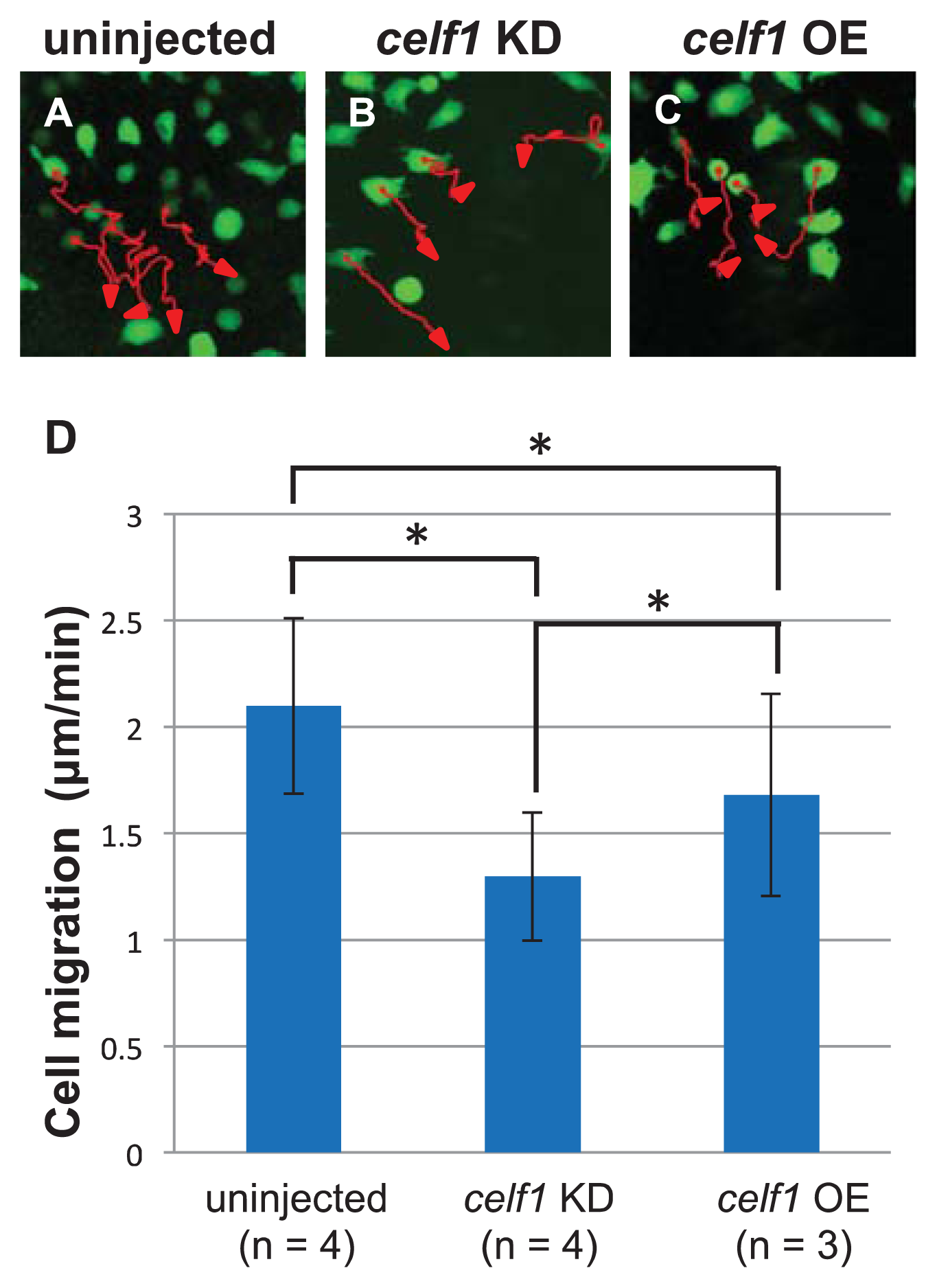

2.3. Celf1 Regulates Endoderm Cell Migration during Gastrulation

2.4. Celf1 Binds to gata5 and cdc42 mRNAs In Vivo

2.5. Celf1 Targets

2.6. Roles of Celf1 in Generation of Endoderm-Derived Organs

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Zebrafish and Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization

3.2. Morpholino and mRNA Injection

- control-MO: 5′-CCTCTTACCTCAGTTACAATTTATA-3′;

- celf1_long-MO: 5′-GCTTCAGCTTCGATACTATCCATCC-3′ [13];

- celf1_short-MO: 5′-GTGGTCCAGAGACCCATTCATCTTC-3′ [13].

3.3. TUNEL and Immunofluorescence Analyses

3.4. BrdU Labeling and Detection

3.5. Imaging of Fluorescence Signals

3.6. RNA Immunoprecipitation (RIP) Assay

- gata5-F: 5′-TGGTGTGCTCTGTCTCAAGC-3′;

- gata5-R: 5′-GCTTTCCTAAGCACCGTCTG-3′;

- cdc42-F: 5′-GACAGTAGCCCTGTAAATGGTTG-3′;

- cdc42-R: 5′-GTTAGAAAGTTCCCTGCTTGAGAG-3′;

- ccna1-F: 5′-CTCCCACAATCCACCAGTTT-3′;

- ccna1-R: 5′-AATCACAGCCAGAGAGTAACCAG-3′.

3.7. Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

3.8. Statistics

4. Conclusions

Appendix

Supplementary Files

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barreau, C.; Paillard, L.; Mereau, A.; Osborne, H.B. Mammalian CELF/Bruno-Like RNA-Binding proteins: Molecular characteristics and biological functions. Biochimie 2006, 88, 515–525. [Google Scholar]

- Vlasova, I.A.; Tahoe, N.M.; Fan, D.; Larsson, O.; Rattenbacher, B.; Sternjohn, J.R.; Vasdewani, J.; Karypis, G.; Reilly, C.S.; Bitterman, P.B.; et al. Conserved GU-Rich elements mediate mRNA decay by binding to CUG-Binding protein 1. Mol. Cell 2008, 29, 263–270. [Google Scholar]

- Vlasova-St Louis, I.; Dickson, A.M.; Bohjanen, P.R.; Wilusz, C.J. CELFish ways to modulate mRNA decay. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1829, 695–707. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, N.; Sasagawa, N.; Suzuki, K.; Ishiura, S. The CUG-Binding protein binds specifically to UG dinucleotide repeats in a yeast three-hybrid system. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2000, 277, 518–523. [Google Scholar]

- Marquis, J.; Paillard, L.; Audic, Y.; Cosson, B.; Danos, O.; le Bec, C.; Osborne, H.B. CUG-BP1/CELF1 requires UGU-Rich sequences for high-affinity binding. Biochem. J 2006, 400, 291–301. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.E.; Lee, J.Y.; Wilusz, J.; Tian, B.; Wilusz, C.J. Systematic analysis of Cis-Elements in unstable mRNAs demonstrates that CUGBP1 is a key regulator of mRNA decay in muscle cells. PLoS One 2010, 5, e11201. [Google Scholar]

- Rattenbacher, B.; Beisang, D.; Wiesner, D.L.; Jeschke, J.C.; von Hohenberg, M.; St Louis-Vlasova, I.A.; Bohjanen, P.R. Analysis of CUGBP1 targets identifies GU-Repeat sequences that mediate rapid mRNA decay. Mol. Cell Biol 2010, 30, 3970–3980. [Google Scholar]

- Beisang, D.; Rattenbacher, B.; Vlasova-St Louis, I.A.; Bohjanen, P.R. Regulation of CUG-Binding protein 1 (CUGBP1) binding to target transcripts upon T cell activation. J. Biol. Chem 2012, 287, 950–960. [Google Scholar]

- Graindorge, A.; le Tonqueze, O.; Thuret, R.; Pollet, N.; Osborne, H.B.; Audic, Y. Identification of CUG-BP1/EDEN-BP target mRNAs in xenopus tropicalis. Nucleic Acids Res 2008, 36, 1861–1870. [Google Scholar]

- Masuda, A.; Andersen, H.S.; Doktor, T.K.; Okamoto, T.; Ito, M.; Andresen, B.S.; Ohno, K. CUGBP1 and MBNL1 preferentially bind to 3′ UTRs and facilitate mRNA decay. Sci. Rep 2012, 2, 209. [Google Scholar]

- Gautier-Courteille, C.; le Clainche, C.; Barreau, C.; Audic, Y.; Graindorge, A.; Maniey, D.; Osborne, H.B.; Paillard, L. EDEN-BP-dependent post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression in Xenopus somitic segmentation. Development 2004, 131, 6107–6117. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, C.; Gautier-Courteille, C.; Osborne, H.B.; Babinet, C.; Paillard, L. Inactivation of CUG-BP1/CELF1 causes growth, viability, and spermatogenesis defects in mice. Mol. Cell Biol 2007, 27, 1146–1157. [Google Scholar]

- Matsui, T.; Sasaki, A.; Akazawa, N.; Otani, H.; Bessho, Y. Celf1 regulation of dmrt2a is required for Somite symmetry and left-right patterning during zebrafish development. Development 2012, 139, 3553–3560. [Google Scholar]

- Mizoguchi, T.; Verkade, H.; Heath, J.K.; Kuroiwa, A.; Kikuchi, Y. Sdf1/Cxcr4 signaling controls the dorsal migration of endodermal cells during zebrafish gastrulation. Development 2008, 135, 2521–2529. [Google Scholar]

- Field, H.A.; Ober, E.A.; Roeser, T.; Stainier, D.Y. Formation of the digestive system in zebrafish. I. liver morphogenesis. Dev. Biol 2003, 253, 279–290. [Google Scholar]

- Field, H.A.; Dong, P.D.; Beis, D.; Stainier, D.Y. Formation of the digestive system in zebrafish. II. Pancreas morphogenesis. Dev. Biol 2003, 261, 197–208. [Google Scholar]

- Matsui, T.; Bessho, Y. Left-Right asymmetry in zebrafish. Cell. Mol. Life Sci 2012, 69, 3069–3077. [Google Scholar]

- ZFIN. Zebrafish celf1 Data for this Paper Were Retrieved from the Zebrafish Information Network (ZFIN); University of Oregon, Eugene: OR, USA. Available online: http://zfin.Org/ (accessed on 24 June 2013).

- Hashimoto, Y.; Suzuki, H.; Kageyama, Y.; Yasuda, K.; Inoue, K. Bruno-like protein is localized to zebrafish germ plasm during the early cleavage stages. Gene Expression Patterns 2006, 6, 201–205. [Google Scholar]

- Matsui, T.; Thitamadee, S.; Murata, T.; Kakinuma, H.; Nabetani, T.; Hirabayashi, Y.; Hirate, Y.; Okamoto, H.; Bessho, Y. Canopy1, a positive feedback regulator of FGF signaling, controls progenitor cell clustering during Kupffer’s vesicle organogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 9881–9886. [Google Scholar]

- Reiter, J.F.; Alexander, J.; Rodaway, A.; Yelon, D.; Patient, R.; Holder, N.; Stainier, D.Y. Gata5 is required for the development of the heart and endoderm in zebrafish. Genes Dev 1999, 13, 2983–2995. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Wei, C.; Olena, A.F.; Patton, J.G. Regulation of endoderm formation and left-right asymmetry by mir-92 during early zebrafish development. Development 2011, 138, 1817–1826. [Google Scholar]

- Roszko, I.; Sawada, A.; Solnica-Krezel, L. Regulation of convergence and extension movements during vertebrate gastrulation by the Wnt/PCP pathway. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol 2009, 20, 986–997. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Bermudo, M.D.; Alvarez-Garcia, I.; Brown, N.H. Migration of the drosophila primordial midgut cells requires coordination of diverse PS integrin functions. Development 1999, 126, 5161–5169. [Google Scholar]

- Matsui, T.; Raya, A.; Kawakami, Y.; Callol-Massot, C.; Capdevila, J.; Rodriguez-Esteban, C.; Izpisua Belmonte, J.C. Noncanonical Wnt signaling regulates midline convergence of organ primordia during zebrafish development. Genes Dev 2005, 19, 164–175. [Google Scholar]

- Blech-Hermoni, Y.; Stillwagon, S.J.; Ladd, A.N. Diversity and conservation of CELF1 and CELF2 RNA and protein expression patterns during embryonic development. Dev. Dyn 2013, 242, 767–777. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd, A.N.; Charlet, N.; Cooper, T.A. The CELF family of RNA binding proteins is implicated in cell-specific and developmentally regulated alternative splicing. Mol. Cell Biol 2001, 21, 1285–1296. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd, A.N.; Nguyen, N.H.; Malhotra, K.; Cooper, T.A. CELF6, a member of the CELF family of RNA-binding proteins, regulates muscle-specific splicing enhancer-dependent alternative splicing. J. Biol. Chem 2004, 279, 17756–17764. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd, A.N.; Stenberg, M.G.; Swanson, M.S.; Cooper, T.A. Dynamic balance between activation and repression regulates Pre-mRNA alternative splicing during heart development. Dev. Dyn 2005, 233, 783–793. [Google Scholar]

- Brimacombe, K.R.; Ladd, A.N. Cloning and embryonic expression patterns of the chicken CELF family. Dev. Dyn 2007, 236, 2216–2224. [Google Scholar]

| Embryo | Cell death (times/h) | Cell division (times/h) |

|---|---|---|

| control (n = 3) | 0.11 ± 0.16 | 27.77 ± 3.72 |

| celf1 KD (n = 4) | 0 ± 0 | 17.00 ± 3.32 * |

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Tahara, N.; Bessho, Y.; Matsui, T. Celf1 Is Required for Formation of Endoderm-Derived Organs in Zebrafish. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 18009-18023. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms140918009

Tahara N, Bessho Y, Matsui T. Celf1 Is Required for Formation of Endoderm-Derived Organs in Zebrafish. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2013; 14(9):18009-18023. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms140918009

Chicago/Turabian StyleTahara, Naoyuki, Yasumasa Bessho, and Takaaki Matsui. 2013. "Celf1 Is Required for Formation of Endoderm-Derived Organs in Zebrafish" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 14, no. 9: 18009-18023. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms140918009