1. Introduction

Highlighting the overall cultural heritage of a region through web mapping is the issue in this project. Kynouria constitutes the area of interest, a region lying on the east coast of the Peloponnese. Mount Parnon, the Argolic Gulf, and the Myrtoan Sea are its natural borders. Today a part of the prefecture of Arcadia, Kynouria had a turbulent trajectory during ancient times. For almost a millennium, both Argives and Spartans claimed territorial sovereignty over this region, even after the Roman intervention in Greek matters. Monuments from ancient times are spread throughout the region, constituting a very interesting and unique ensemble—along with the natural surroundings—both in short- and long-term view.

Given the economic situation and the need for rationalization of the decision-making process, an implementation is required that will allow the fewest possible means and resources to achieve the key objectives of the promotion, accessibility, and protection of antiquities on the one hand and on the other their integration into the given social and economic context so that they can be used as a keystone for local growth.

Search for similar applications via the websites of municipalities and regional entities usually gives the same result: a section of the website is devoted to the sights, accompanied by a description and maybe a built-in Bing or Google map. In rare instances, the map depicts the locations of attractions, and even more rarely, it includes some suggested routes. Something similar happens in most climbing sites and hiking clubs, where social networks are widely used. All these considered, several different proposals are more attractive and technologically up to date.

Archaeological Museum of Tegea [

1,

2]: A very impressive web presence, with multilingual support and great photos. The strong point of this website is the clear and interactive maps and the 360° virtual tours to exhibits, the interior of the museum and the monuments that lie outside the area of the museum, and the 3D representations. This site was the base-model on which we relied for the preparation of this work; it is the complete website concerning Greek archaeological sites and technically is more suitable to the application under discussion because the Museum’s website was created in ASP.

Kentucky’s state forests [

3]: A key feature is the use of virtual travel maps and targeted information, based on a combination of maps and images. Although it is not an archaeological site (it projects forests and routes in nature), we adopted the main idea of presentation in order to meet our needs. It was also built using a software tool called “ArcGIS,” the online version of which is free and suitable to prepare our project before serving it on a website.

Transromanica [

4]: The “Transromanica Association” is focused on the common cultural heritage of the Romanesque art and architecture of eight countries in Europe between the Baltic and the Mediterranean Sea (Greece is not included). It provides facilities sorted by region, such as tourist boards and offers, searches for heritage (monasteries, churches, cathedrals, highlights, and others), search for events, and an interactive Bing map.

“Monopatia politismou” [

5] (translated as “Greek Paths of Culture”): A project for the protection of the environment and our cultural heritage. By selecting a series of walks, and with careful signposting and communication, paths were made accessible and attractive again. This website is characterized by a youthful style, simplicity, and net information, which is not limited herein, as it also combines images and videos. This project is useful to lovers of nature, but it does not contain any significant information about antiquities since it is not an archaeological site. Therefore, the main idea of the developers is very close to ours.

1.1. Monuments and the Development Process

The transition in the attitude on the recognition of the value of cultural—and specifically of the value of archaeological—heritage is now a fact. Culture is a driving force of the economy [

6]. Cultural heritage contributes to the economic and social development and this is a much more qualitative approach than the approach suitable for a mere commercial product. Grigorakakis [

7,

8] rightly claims that culture is a public good and common heritage of humanity, and that is the main reason for which we have to maintain and highlight it. This approach implies that cultural heritage can be another important tool for local economic development, considering the dimension of how to attract more travelers. Among the most common and important conditions for selection of tourist destinations is the enhanced natural and cultural environment. This is a reason for self-questioning about how areas of tourism should properly exploit their cultural heritage, avoiding disruption of existing economic and social fabric, how individuals can earn from activities performed by focusing on those areas, and how to further protect cultural heritage and diminish the possible threats from tourist activity to it. The impacts from tourism are not related exclusively to the environment, both cultural and natural, but can spread throughout the local community. Therefore, evaluation and estimation of possible threats and the establishment of a mechanism aiming at planning and preventing possible threats and damages to the natural or human environment.

Peters [

9] mention that, no matter how many studies have been done on the subject of tourism of any kind, we are not yet in a position to speak with certainty about the acceptance or not of the local population in understanding the importance of cultural heritage and its exploitation. Human behavior is not easily measurable and depends on many factors, such as education and current social conditions [

10]. In Greece, it is historically proved that, even in times of wars and long-term slavery, the inhabitants respected their cultural heritage and protected it. Sometimes, when they were routed out of their homes, they preferred to take with them objects of their cultural heritage at the expense of their personal items. In general, costs and benefits of tourism are categorized as economic, environmental, and socio-cultural; it often happens to decide on the use of cultural heritage, using a reasonable “win or lose” [

10]. A key point described by [

9,

10] is that the impacts of those categories are closely linked. Greece has the advantage of a very rich cultural heritage and the disadvantage of having a destroyed economy, due to many war and slavery periods of the last two centuries, and due to political instability. Cultural heritage, exploited with respect, was one of the vehicles for “winning” the development. This is an interesting case study, where some positive and negative results from the exploitation of the cultural heritage can be found at [

11].

What is requested therefore is to find the golden mean, according to the model of “sustainable development.” Cultural goods should be more appealing and open to a greater number of people. Technological aids are suitable for such changes; GIS does a better job of sharing data and information than knowledge [

12].

1.2. Alternative Forms of Tourism—The Cultural Tourism

It is expected that some questions will be asked, which should be answered before deciding whether the use of cultural heritage is ultimately positive. Will cultural tourism attract investment? Will the cost of living for the locals be increased disproportionately? How many people will benefit? Will new jobs be created? If so, how many locals will be occupied? Will the natural environment be protected? Will there be an opportunity to improve infrastructure? If so, can these structures protect the current cultural identity? Who guarantees that noise, crime, and pollution will not be increased? Peters, M., et al. [

9] shows the results of a very interesting questionnaire related to our subject, and Guo, Y., et al. [

13] focuses on the local adaptive capacity and the community resilience, based on human psychology and some scenarios.

Peters, M., et al. [

9] and Psychogyios, D., et al. [

14] both agree—based on many previous studies—that such questions either raise new complex social problems or solve some preexisted problems. The fact is that cultural tourism is today recognized as one of the most important forms of tourist traffic in the world, and its popularity and importance are increasing. Meeting tourists from all over the world is a valuable experience, and people need to link themselves to ancient populations, to make all ancient habits as their own heritage and to feel proud with their history [

15]. Cultural tourism is usually targeted to travelers with high educational and cultural levels who appreciate the treasures of the past.

It is obvious that there are preconditions exploiting cultural tourism to have many positive effects on tourism development and to reduce the spoilage that comes along with mass tourism. This work is focused on the technical resources available in order to exploit this cultural capital. Greece (especially inland Greece) has many hidden cultural treasures, most of which are ready to be highlighted and protected and ready to be offered to local citizens and to the whole world; culture has to be lived [

6].

Niemczyk [

16] shows the importance of culture when deciding to visit a destination. Monuments and museums and everything that is close to culture are highly ranked, and it is worth using fresh technological tools to exploit cultural tourism. Pilgrimage route travelers are also increasing in numbers. Religious monuments are also cultural heritage. Many people love to follow paths using either the growing and growing planning literature or just empirical oral instructions to worship a religious monument and enjoy the natural scenery. It is not just about recreation in the strict sense of the word; it is often directly related to inner and spiritual theological experiences. This approach particularly touches Greece and Orthodox heritage everywhere. The religious monuments of orthodoxy are not just architectural creations. Orthodoxy is not a religion like all others but is Resurrection, Revelation, and Life [

17,

18].

1.2.1. The Cultural Routes

Shaping cultural routes is the most important means of exploiting cultural heritage—in this case at the European level. Along these routes, there are areas that are important from a cultural standpoint, such as attractions, monuments, and museums, which are either less known or even completely unknown to the general public. Cultural routes are networks that sometimes integrate incoherent and isolated cultural resources. In these areas can coexist archaeological sites, museums of all kinds, fortifications, churches, and monasteries, acquaintance with which refers to a type of tourism both quantitatively and qualitatively different from the pattern of mass tourism, with specific quests and sensitivities. Niemczyk [

16] quotes a matrix approach showing that cultural routes can be a useful tool in the hands of the tourists, which may enhance the popularity of reception of culture at the destination and attract even more people.

1.2.2. Cultural Landscapes: The Place of Kynouria in Arcadia

Kynouria today is the south-east regional unit of Arcadia.

Figure 1 shows the exact area of Kynouria in Peloponnese (Greece). Historically, except for a short period, it was never a part of Arcadia. The dominant presence of Mount Parnonas and the sea have determined its character and historical destiny.

This region is administratively divided into two major sections, the Municipalities of North and South Kynouria, and has a particularly remarkable cultural heritage, which is a combination of a natural environment of special beauty, almost intact from human activities. It is also a popular tourist destination.

The cultural importance of Kynouria covers the entire historical span, from prehistory until modern times. Never before has there been any effort to highlight any of these areas (with the exception of the famous Villa of Herodes Atticus in Eva), and the monuments are in most cases inaccessible. The proposal is not focused on a single area or monument but on a comprehensive, thematic treatment of monuments and sites, which date mostly from the classics to the Roman times, within the scope of classical archaeology [

19].

The concept of “cultural route” is used here as a tool of exploitation of cultural heritage. The method followed is from the overall to the individual (top-to-bottom). Cities-ports of Kynouria is the subject of this work.

1.3. Open-Source Tools Available for Our Work

Gamalielsson, Reilly and Williams, and Hepburn [

20,

21,

22] mention some of the advantages of using open standards, which suit to our case study: we have the minimum risk of being technologically locked-in, while we gain interoperability, long-term access, and reuse of digital assets. There was no need to lock our source code, and we wanted to use freely available and customizable open-source code, with open access available to all. That is how we realized about highlighting and serving of a “public good.” That is why we chose Drupal as our main software background, which promotes its advantages in scalability, personalization, user management, database management, the creation of innovation platforms, and so on [

20,

23].

In fact, there are some CMS that are open and designed especially for cultural applications. Caffo [

24] mentions “Museo & Web” [

25] and MOVIO and states that “Museo & Web” is a stable and open-source CMS especially devoted to cultural institutions (e.g., museums, libraries, archives) that want to build a website using specialized software modules. For cultural institutions, ICCU created a new application to develop virtual exhibitions online which was made possible thanks to the MOVIO project. MOVIO developed a toolkit that consists of an open-source CMS for the creation of online virtual exhibitions, the equivalent version for mobiles (iPhone, Android for smartphones, and iPad), the version of App for popular mobile platforms (iMovio), and online tutorials and training.

Although “Museo & Web” is stable, updated, and improved, has a great active Google support group [

26], and could be a preferred solution for specific needs, we faced a problem: website and the tutorial of “Museo & Web” was not multilingual; it was only available in Italian at the time of the project. As for “MOVIO,” there was not a website to download and use it while we were preparing the project.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Model Highlighted—General Purpose and Main Idea for Kynouria’s Monuments

Aksenov [

27] highlights that assistance to tourists using tour guides offers a significant information filtering and categorization; the next step is to choose which of this information is relevant to their needs. For the case of Kynouria, in order to achieve the main objective that cannot be other than the protection of antiquities, a new standard of highlighting individual monuments and sites is proposed. Therefore, natural and cultural environment as well as census data are essential as far as the project planning is concerned, given the supplementary dimension (monuments, natural environment, social and economic activity) of the approach proposed and the cohesive axis of the whole project summarized as “Poleis (cities) of Kynouria.”

Promoting the antiquities of Kynouria should be done on a new basis, as this area is a collection of medium and small archaeological sites. Grigorakakis [

8] proves that these antiquities cannot be offered for local economic exploitation but should be promoted and protected based on the concept of “public goods.”

The main principles for highlighting Kynouria’s monuments should be

A design based on the values that these monuments embody;

Mild elevation accessibility;

Networking routes;

Complementary actions by the Greek Ministry of Culture and Tourism, the local authorities’ infrastructure, the local communities, and the private sector.

This work aims at creating some kind of a digital, open Museum, which will not represent any building, but the monuments themselves, as they are in their natural environment, and provide the visitor all necessary information online about how they can access them and what they can see. The impressions of the visitors are complete (anthropogenic and broader natural environment) and in an experiential way, as they are called to discover the monuments and be initiated in the history of the region.

Therefore, the main scenario of the network proposed aims at

Unifying North and South Kynouria;

Highlighting the settlement patterns both in the short and long term;

Highlighting the general geographic orientation of the settlement pattern toward the seashore;

Highlighting the strategic position of the region at the entrance of the Argolic Gulf and the eastern shoreline of the Peloponnese between Argolida and Laconia, as a gateway to and from Central and Southern Peloponnese.

In this way, a cohesive framework will be formed, which will allow for an understanding of the historical trajectory of the region, in conjunction with the natural environment of Kynouria and its unique natural beauties, which the visitors are called to discover, evaluate, and protect.

2.2. Historical-Archaeological Parameters Concerning Kynouria—The Present Status

Kynouria’s tourism product is diversified and includes both the natural and the man-made environment. It is very close to the center of Peloponnese, to popular leisure tourist destinations (such as Nafplio, Vitina, and the Argosaronikos Islands), and to popular archaeological destinations (Mikines, Tirintha, Argos, Epidavros, Nemea, and Sparti). West Kynouria is shaped with mountains, east Kynouria has many plains and beaches, and the whole area has a unique cultural and historical heritage from prehistory until today, as Grigorakakis [

8] analyzes in his work. Some historical key points are as follows:

The population of Kynouria was amid two powerful Doric States of the historical times, Argos and Sparta, which both battled for the supremacy of the whole area.

The conflict for the predominance of the two major Peloponnesian forces took place in Kynouria.

Kynouria was intensely inhabited in antiquity along the coastline or at a short distance from it. Some of the proven archaeological places, where walls of cities-ports and acropolis were towered, are Tsiorovos, “Nisi” of Astros coast, ancient Eva, Cheronissi, “Nisi” of Agios Andreas coast, ancient Tyros, Plaka Leonodiou, and Vigla near Poulithra. Near these, we can meet the famous ancient temples of Apollonos Tyrita and Artemis Orthias, Polemokratous, and Eva. Posterior monuments are Villa of Herodes Atticus and the buildings at the coast of Astros, Agia Anastassia, Plaka Leonidiou, and “Nisi” of Agios Andreas.

The antiquities are arranged near the main road that runs through the coastline of Kynouria from Xiropigado to Poulithra. Some of these antiquities have direct interconnections to this main road. This road ends to Astros and through the provincial road of Astros-Tripolis interconnects to the highway of Peloponnese. Three main modern towns and many villages are very close to them (Astros, Tyros, and Leonidio). Most of the local infrastructure is concentrated there, and there is an increase in tourist traffic during the summer months. There are also ports and fishing shelters nearby (coast of Astros, Agios Andreas, Tyros, Plaka Leonidiou, and Poulithra).

The natural environment has not yet been affected and has many beautiful natural areas (as shown in

Figure 2), wetlands, olive farms (in Pausanias’ time), etc. Finally, two points of interest are the Archaeological Museum of Kynouria placed at Astros and the Open-Air Museum at Villa of Herodes Atticus in Eva of North Kynouria.

2.3. The Routes

A typical target user of such a recommender system is a tourist who is interested in exploring a (historical part of a) city and therefore would like to make a tour through this city or its part on a particular day. The tour involves visiting several points of interest (POI)—sites of specific interest to the tourist—that may be spatially dispersed across the city area, implying that traveling may be involved in implementing the tour. Points of interests can be logically linked with each other in a way that creates a storyline that the tourist will be interested to follow, which adds to the tour’s cultural value [

27].

For the case of Kynouria, Grigorakakis [

8] analyzes the routes across the antiquities, using the main route called “Cities: Acropolis—ports of Kynouria,” which extends from North to South and three subdivisions of the main route; two of them concern North Kynouria, and the other is about South.

Figure 3 shows in detail all the monuments. Using villa of Herodes Atticus and the Archaeological Museum of Astros as the focal points, the following sub-routes are formed as mentioned below:

North Kynouria

Ancient Eva—according to Pausanias, this is the most important site in Thyreatida. This route includes the ancient acropolis in Tichio, Polemokration, and the villa of Herodes near the Holy Monastery of “Metamorfossi tou Sotiros” in Loukou,

Cities-ports of North Kynouria, which include “Teichos Aiginiton,” “Kastraki” Meligous, and the acropolis of Agios Andreas and

The defense network of Zavitsa, which contains the watchtowers of mount Zavitsa and the ancient acropolis of “Tsiorovo.”

South Kynouria

Cities and ports of south Kynouria, which contains ancient Tyros, the ancient Acropolis at Plaka Leonidiou, and Poulithra,

Ancient Tyros—the temple of Apollon Tyritas.

2.4. The Technological Tools

Creation of suitable databases and portraying their data in space are necessary steps. The latest technology, such as GIS, GPS, and OMS (also known as web mapping), is a very important tool for designing, data recording and mapping, correlations display, and publishing the result.

The use of GIS certainly reinforces this idea that science and practical problem-solving are no longer distinct in their methods [

19]. As shown by Latinopoulos and Kechagia [

28], GIS has emerged over the recent years as an essential tool for spatial planning and management. Therefore, its application can be particularly valuable not only for visualization and data management but also for the assessment of choice alternatives based on spatially related criteria.

The mass production process of the digital geographic infrastructure of a region and its constant maintenance require actions that have a methodology that certainly depends on who is going to use and utilize this infrastructure. However, almost always, a significant part of this infrastructure depends on the geomorphology, the physiography, and all the data resulting from the intervention of humans around the region being studied. The conceptual model identifies the needs of the users, the objects that participate in the creation of the database depending on the theme of the content (in this case, archaeology), the relationships between those objects, and the form in which they will be represented in the database. A geographic database cannot contain a perfect description—instead, its contents must be carefully selected to fit within the limited capacity of computer storage devices.

The software of a GIS captures and implements general knowledge, while the database of a GIS represents specific information. In that sense, a GIS resolves the old debate between nomothetic and idiographic camps by accommodating both. GIS solves the ancient problem of combining general scientific knowledge with specific information and gives practical value to both [

19].

2.5. Geospatial Data Used

Geospatial data is used in critical decision making across industries, and it is increasingly important to understand an area of interest and utilize the data to make even more accurate spatial decisions. GIS lets us visualize, question, analyze, and interpret data to understand relationships, patterns, and trends. In addition, a GIS allows us to show relationships and trends and to model features to suit our needs. Layers in a GIS gives people the power to ask pertinent questions that drive development and develop scenarios, break down complex problems and devise strategies to make the process better [

29].

Important information about the close relationship between the archaeologists and the information technology have provided by a related project held from Research Laboratory of Geospatial Technology at the University of West Attica in cooperation with the Ephorate of Antiquities in Arcadia [

30]. Spatial analysis of the archaeological-historical data was introduced and an innovative archaeological interest geographical database application named “Calisto” is already designed and elaborated. “Calisto” cooperates with existing MIS related to the Greek antiquities. The establishment of this geographical database aims to facilitate the permanent needs of the archaeologists regarding organization, management and documentation of archaeological finds in an administrative section of the country (e.g., for Arcadia and even more for Kynouria). “Calisto” designers implemented it with respect to the standards of the geographical databases, considering the needs of future users for the data management and the ability for managing, populating and updating the data. “Calisto” constitutes the infrastructure for the organization of the entire geospatial background of the Ephorate of Antiquities in Arcadia.

Our data was retrieved from the above database. We imported geospatial data from “Calisto” into ArcGIS online software by ESRI as shapefiles, containing the information we needed.

Callisto’s data came mainly from on-site measurements, which are distinguished in

- (a)

Topographic surveys;

- (b)

Photogrammetric surveys, mainly from technical works on the road Tripolis-Kalamata-Sparta, refer to burial and other finds discovered along this project and have orthophoto maps derived from low flights.

Therefore, both data categories gave accurate and reliable results, geo-referenced in the National Geodetic Reference System 1987 and produced in scales ranging from 1:200 to 1:1000, except for two exceptions (1:5000).

With regard to the category of elements that are not purely archaeological, irrespective of the relationship that arises between them and the archaeological ones, they exist in two forms:

- (a)

Vector data derived from design in CAD software and even on large scales e.g., 1:500 or 1:1000. There were also vector data used mainly by GIS software such as shp, feature classes, but also spreadsheets containing descriptive information about monuments (descriptions, names) as well as coordinates of archaeological sites, and

- (b)

Raster data mainly referring to scanned topographic maps of the Hellenic Military Geographical Service, orthophoto maps of the Ministry of Rural Development, digital terrain models and scanned topographical diagrams of archaeological sites with excavated information.

In

Figure 4, the contents of the Geodatabase are represented.

2.6. Accompanying Data Used

Geospatial data are better understood—and this is a way of taking full advantage—when they are accompanied by some extra data that are not characterized as “geospatial” but refer to it. In our case, this extra data consists of some digital photographs of the area of our interest and photographs or drawings of maps (stored as files on the computer). The digital frames of the areas are taken “on-site” in a way that describes specific information concerning each antiquity. It is suggested these photographs to be taken either by professionals or photographers accompanied by archaeologists—or at least by the archaeologists themselves—in order to imprint the right monuments using the correct perspective and the appropriate dimensions, resolution and color depth. That is why we used digital photographs. Some examples can be seen in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6.

2.7. Software Implementation

A software implementation is needed to extend the entire idea to the final user. The best solution would be an implementation that could be available online and managed by a portable device, such as a smartphone, a tablet, or even a laptop. With recent advancements in technology, the proliferation of the internet, and the adoption of mobile and pervasive computing paradigms, recommended systems for tourists have also joined the world of mobile devices and have become available on the fly [

27].

When all data were compiled, they were transformed into digital form using the advantages of the “Calisto” geographical database. Some information about this special-purpose database is given below.

2.7.1. Choosing a GIS Software

Once all the necessary digital maps had downloaded and collected, a suitable GIS software, ArcGIS online, was used to manage them and produce the final maps. ArcGIS by ESRI™ provides a free online platform for including maps and scenes and allows users to explore and understand the geographic data. The interactive maps found in ArcGIS allow exploring, visualizing, and understanding data in 2D. Data-viewing tools, such as pop-ups, legends, and filters, allow the user to focus on the important data. The idea of a serving application using 2D maps is not an innovation; in general, 2D mapping applications provide an intuitive interactive and visualization environment for users [

20].

2.7.2. Configuring ArcGIS Online

We did not use any of the included maps of ArcGIS online, but we created a new web map and imported our shapefiles as layers, performing all necessary modifications to produce our final main 2D map of Kynouria (as seen in

Figure 7). This final web map contains suitable bookmarks, which zoom to specific areas. The final map also contains some useful navigation controls.

Zoom in and zoom out buttons (it also supports the mouse and scroll wheel, the arrow keys on the keyboard and press-and-hold of the Shift key and then drag a box on the map);

Zoom the map to its initial extent and browse the map to a predefined extent through a bookmark (as already described above);

Pan using mouse and scroll wheel or the arrow keys on the keyboard;

Find a current location (GPS sensor is required).

Some other features that we have enabled are

View a legend, which displays the meaning of the symbols used to represent features on the map.

Measure. When using the main map, the area of a polygon and the length of a line can be calculated. The coordinates of a point can also be found. The map viewer calculates the shortest distance (using the ellipsoid-based geodesic calculation). Before or after performing each measurement, the user can change the default units of measurement.

Figure 8 shows such an example for calculating the Euclidean distance between Astros and ancient Tyros.

Share the map by sending an email with a link, posting it on a Facebook or Twitter account, or embedding it in a website or blog.

Select a base-map. A base-map provides a background of geographical context for the content that must be displayed in a map; the user can choose which base-map to use and change the base-map of the current map at any time by using the base-map gallery.

We had to create three more main web maps based on the main web map, one sub-main map for each sub-route, and use them in our final web application. All features and navigation controls described above are available for all these web sub-maps. Finally, we created some web applications based on the above web maps. Web applications were necessary to provide more information in a friendly way. We created different configurable apps that offer various bits of functionality, such as different layouts and color schemes, editing and identify tools, social media feeds, side-by-side map viewers, and so on. Web applications use built-in JavaScript APIs [

31]. Specifically, three web applications were created: a base-map web application, to be displayed on the front page of our final application, a storyboard, which is something like a guided virtual tour and contains text information about all antiquities, including photos and a map journal, which demonstrates a classic printed map, containing information in text and image presentation of grouped routes. It is obvious that we created the three sub-main web maps described above to create this map journal web application.

2.7.3. Setting Up the Application

ArcGIS online gives many choices and excellent outputs, but there was a need for serving all these results to an independent and stand-alone application. The best solution was to create a client-server application. As we did when choosing the open-content solution of ArcGIS online, which supports free use, we preferred again a complete open-source solution: a piece of software for a local web server, a suitable database, and a CMS. For our local web server implementation, we chose XAMPP; for CMS, we chose Drupal; a typical MySQL database, created and managed using PHPmyAdmin, fills the package. In general, the whole functionality of our application is shown in

Figure 9.

In

Figure 10, a compact Unified Modeling Language (UML) diagram shows the available roles and the interaction between them. Application settings and functionalities that were enabled in the design mode of the maps are also available in the final web map application embedded in the home page: routing (in use only if a GPS sensor is available), measure tool, base-map selector, find location by address, and “find my location” (in use only if a GPS sensor is available). The application is currently in Greek and available online at

http://kynouria.byethost14.com/drupal. The zoom tool provides extra optical information to the user, such as the exact place of the monuments, lines, and polygons referring to the antiquities, main and rural roads, hiking trails, inner tracks, signs, available places for parking, and points of interest. Extra information is revealed at different zoom levels. The user can change the base-map and choose what supplementary information he wants to see, which is available as open-content by ArcGIS online. Pop-ups are also enabled: the user can click on a specific site and view some initial information. Pop-ups are displayed only when the user clicks on a monument and disappear when another pop-up is displayed.

3. Results

A web-GIS platform can be considered as a decision support tool for the tourist’s access to the most varied cultural places by providing information about them (hotels, restaurants, shopping places, public facility, and other tourist attractions). As the power of GIS lies not only in the ability to visualize spatial relationships but also beyond the space to a holistic view of the world with its many interconnected components and complex relationships, and with the integration of GIS and DSS, it can benefit the tourism industry [

32,

33].

The theoretical background of the method we used is based on one of the most commonly used methods for multi-criteria spatial decision-making support systems (or multi-criteria spatial information systems) [

34,

35] called the analytic hierarchy process, which is used to provide non-obvious solutions and alternatives to complex problems [

36]. There is a planning platform for us that provides the required information needed by an average visitor of antiquities and appropriate maps based on scientific data. The suggested routes are supported by photographic material and a live preview of the route, providing modern technological services in a fresh and comprehensible way, as every Web-GIS model should be [

37], which is particularly important for an area of antiquities such as Kynouria, which is far away regarding other monuments in Greece. In contrast to the standard multi-criteria spatial decision-making support systems, the possibility of discussion can be easily activated thanks to the design chosen and the modern technological tools at no extra cost for software, as our implementation is based to open-source projects [

35,

38].

Our application provides a home page, where an embedded a map of Kynouria dominates, that includes an article with a very short historical placement, three menus linking to deeper text information accompanied by enlightening images, and two other menus that activate a photo map tour and a map journal. The embedded map of our home page is created using ArcGIS and provides full functionality of the tools described at

Section 2.7.2 and

Section 2.7.3: a base-map gallery, a measure tool, a list of bookmarks, a button for displaying details of a place, two buttons for zooming in and out, a search section, and the main points of interest visible by default. There is a login section to administrate the application. All visitors to our application can directly use all the above tools without registration and click on a point of interest to view their name, a short description, and its coordinates. This information is provided in a pop-up window, containing a diacritical zoom tool. By clicking on it, the user can see directly the present look of a specific area of the monument (depending on the base map chosen) and the exact place of the monument. All the points of interest are clearly marked with a blue ancient Greek symbol. Every time our visitors zoom in the map, more information is displayed on it.

3.1. Story (and Photo) Map Tour

Story map tour is a more attractive collection of points of interest that are numbered on the map. This section of our project has 12 such points, representing the main sites of each route. Different colors are used to separate the routes (

Figure 11a,b). The points are numbered in a way that the smaller number represents the beginning of the route and the bigger represents the end of the route.

As mentioned above, this is an HTML page, and its role is to offer an attractive way of a virtual touring without providing mass information by text or by images. After following this tour, the user has a primary acquaintance with ancient Kynouria, which is compact but not poor because it offers a very good initial package for touring, containing geographical and archaeological knowledge.

3.2. Map Journal

The last feature of our project is the map journal. It is another HTML page, the content of which is focused on the routes. The main idea is to create something like a digital journal, where the user can combine the reading of the text and watching small videos (which in fact are slideshows with photos of each route, converted to “.mp4” video format) (

Figure 11c,d).

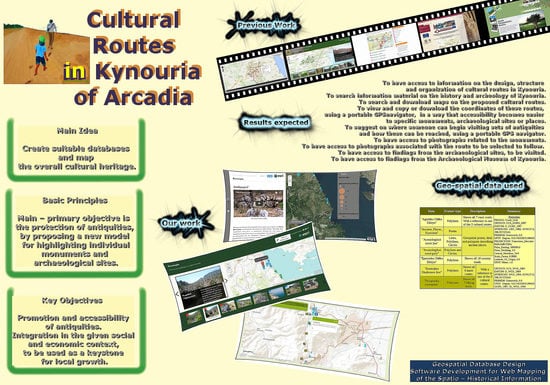

3.3. Expected Results

The results expected can be summarized as follows:

To have access to information on the design, structure, and organization of cultural routes in Kynouria;

To search information material on the history and archeology of Kynouria and download maps on the proposed cultural routes;

To view and copy or download the coordinates of these routes using a portable GPS navigator in a way that accessibility becomes easier to specific monuments, archaeological sites, or places;

To suggest where someone can begin visiting sets of antiquities and how these can be reached, using a portable GPS navigator;

To have access to photographs related to the monuments and to photographs associated with the route to be selected to follow;

To have access to findings from the archaeological sites to be visited and to findings from the Archaeological Museum of Kynouria.

This work relies on scenarios processed by archaeologists, so it is a multimedia application which somehow attempts a documented reconstruction of the history of the area. In this process, GIS has a main role in feeding this application with its results, and the application would simultaneously receive all the necessary archaeological information (texts, images, designs etc.). In this way, the necessary scientific documentation will be achieved, while the scenarios will be interlarded to make them appealing to visitors.

Table 1 shows, in general, some of the advantages and the disadvantages of our work.

We believe that this is an innovative approach of promoting antiquities that are not famous in Greece (like e.g., Acropolis, Delphi, Mikines, and Knossos), providing so much information in an attractive way to everyone plus the available routes to discover them. This web application will be 100% useful and functional if the authorities decide to install Wi-Fi hotspots with free internet access in selected locations (e.g., Archaeological Museum of Kynouria at Astros, Loukou, Tyros, and Leonidio).

4. Conclusions and Future Work

The web application under discussion aspires to be functional, simple to use, and scientifically accurate regarding the data included. The role of the internet in highlighting and promoting monuments and cultural routes is important, especially when geospatial data is used online for smart portable devices, serving searching capabilities to people who love nature and have specific archaeological interests. The goal is to use personalized solutions to highlight cultural heritage as a public good and improve the experience of cultural tourism.

A prerequisite for the full implementation of this web application to become even more attractive and useful is to include

Even more historical and archaeological informational package (such as more text, maps, and photos);

The ability to search for accommodation, travel packages, or other benefits;

The ability to search for stores of sanitary interest, for Museums, for traditional villages etc.;

Even more complete information about how some points of interest can be accessed;

Other attractions worth seeing the visitors under the proposed routes but also in their wider catchment area;

Announcements of all the events that took or will take place in the context of scientific and educational activities of the archaeological authority in the area;

The ability to download reputable books and audio files—both as tour guides for the area and the route that a visitor chooses to follow;

Access to events that local communities are organizing;

Access to web pages of local authorities, local government, local blogs etc.;

Searchable sanitary shops, museums, traditional villages, and so on, all provided by a static and dynamic way, fully exploiting the capabilities of geospatial databases and interactive digital cartography;

Automatic multilingual support or manual full translation into other languages.