The Genetics of Osteoarthritis: A Review

Abstract

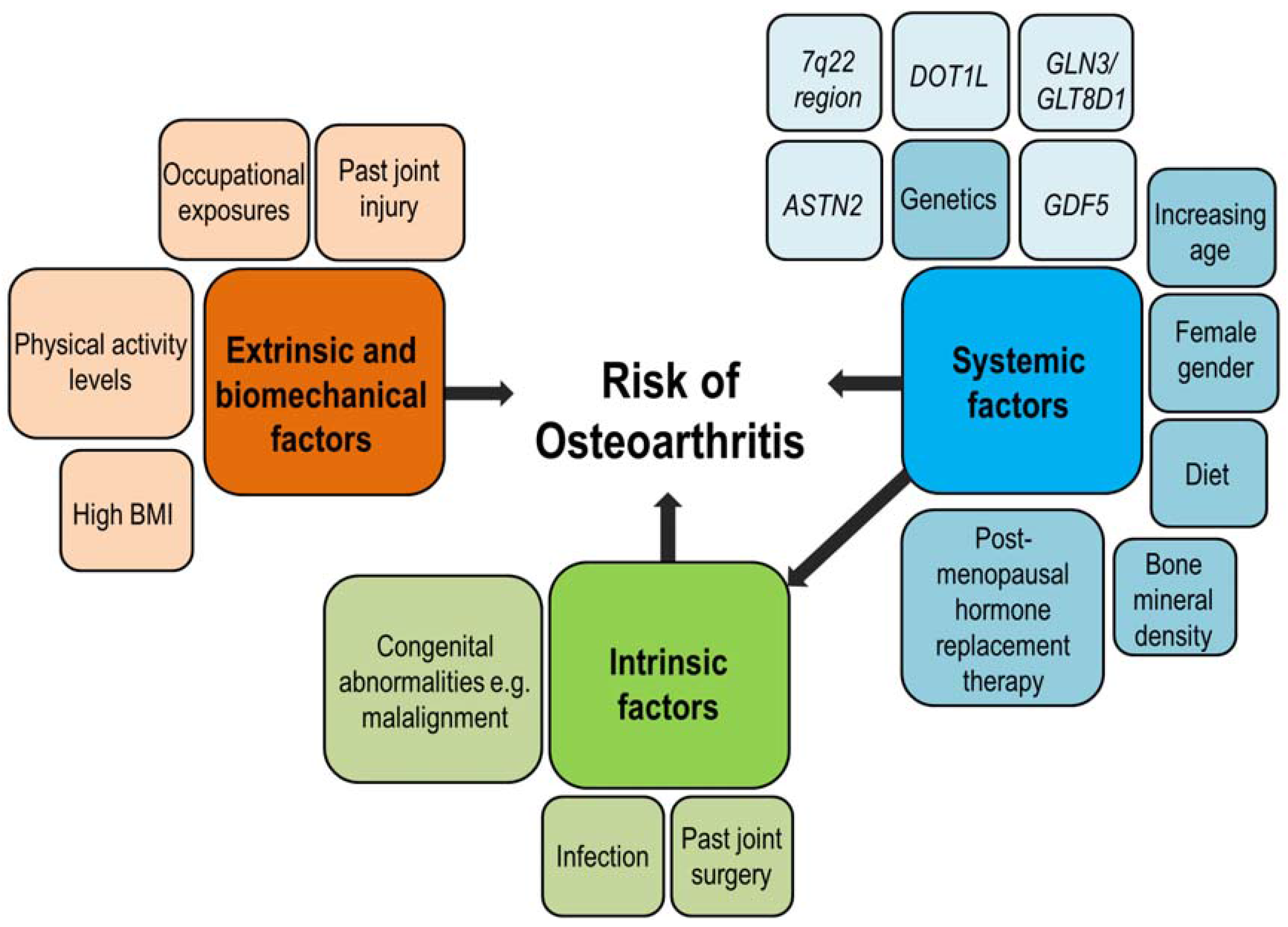

:1. Introduction

2. Heritability of Osteoarthritis (OA)

3. Investigating the Genetic Risk Factors for OA

3.1. Traits and Outcomes Studied in the Genetics of OA

3.2. Pain in OA

4. Genome-Wide Association Studies

4.1. Genome-Wide Association Scans (GWAS) for OA

4.1.1. Background

4.1.2. Early Small-Scale GWAS Findings

4.1.3. Large-Scale GWAS Findings

4.2. What GWAS Has Taught Us about the Pathogenesis of OA

4.3. Clinical Relevance

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OA | Osteoarthritis |

| GWAS | Genome-wide association scan |

| SNP | Single nucleotide polymorphism |

| LD | Linkage disequilibrium |

References

- Dieppe, P.A.; Lohmander, L.S. Pathogenesis and management of pain in osteoarthritis. Lancet 2005, 365, 965–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitton, R. The economic burden of osteoarthritis. Am. J. Manag. Care 2009, 15, S230–S235. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Valdes, A.M.; Doherty, S.A.; Zhang, W.; Muir, K.R.; Maciewicz, R.A.; Doherty, M. Inverse relationship between preoperative radiographic severity and postoperative pain in patients with osteoarthritis who have undergone total joint arthroplasty. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2012, 41, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baugé, C.; Girard, N.; Lhuissier, E.; Bazille, C.; Boumediene, K. Regulation and role of TGFβ signaling pathway in aging and osteoarthritis joints. Aging Dis. 2014, 5, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chapman, K.; Valdes, A.M. Genetic factors in OA pathogenesis. Bone 2012, 51, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeggini, E.; Panoutsopoulou, K.; Southam, L.; Rayner, N.W.; Day-Williams, A.G.; Lopes, M.C.; Boraska, V.; Esko, T.; Evangelou, E.; Hoffman, A.; et al. Identification of new susceptibility loci for osteoarthritis (arcOGEN): A genome-wide association study. Lancet 2012, 380, 815–823. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dreier, R. Hypertrophic differentiation of chondrocytes in osteoarthritis: The developmental aspect of degenerative joint disorders. Arthritis Res.Ther. 2010, 12, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshinari Miyamoto, D.S.; Nakajima, M.; Ozaki, K.; Sudo, A.; Kotani, A.; Uchida, A.; Tanaka, T.; Fukui, N.; Tsunoda, T.; Takahashi, A.; et al. Common variants in DVWA on chromosome 3p24.3 are associated with susceptibility to knee osteoarthritis. Nat. Genet. 2008, 40, 994–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, J.M. Epidemiology and classification of osteoarthritis. In Rheumatology, 4th ed.; Hochberg, M.C., Silman, A.J., Smolen, J.S., Weinblatt, M.E., Weisman, M.H., Eds.; Elsevier: Madrid, Spain, 2008; Volume 2, pp. 1691–1701. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, D.L.H. Informed drug choices for neuropathic pain. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 129–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelber, A.C. Osteoarthritis research: Current state of the evidence. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2015, 27, 273–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aury-Landas, J.; Marcelli, C.; Leclercq, S.; Boumédiene, K.; Baugé, C. Genetic determinism of primary early-onset osteoarthritis. Trends Mol. Med. 2016, 22, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, L. Osteoarthritis year in review 2015: Clinical. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2016, 24, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spector, T.D.; Cicuttini, F.; Baker, J.; Loughlin, J.; Hart, D. Genetic influences on osteoarthritis in women: A twin study. BMJ 1996, 312, 940–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdes, A.M.; McWilliams, D.; Arden, N.K.; Doherty, S.A.; Wheeler, M.; Muir, K.R.; Zhang, W.; Cooper, C.; Maciewicz, R.A.; Doherty, M. Involvement of different risk factors in clinically severe large joint osteoarthritis according to the presence of hand interphalangeal nodes. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 62, 2688–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panoutsopoulou, K.; Southam, L.; Elliott, K.S.; Wrayner, N.; Zhai, G.; Beazley, C.; Thorleifsson, G.; Arden, N.K.; Carr, A.; Chapman, K.; et al. Insights into the genetic architecture of osteoarthritis from stage 1 of the arcOGEN study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011, 70, 864–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Valdes, A.M.; Doherty, S.A.; Muir, K.R.; Wheeler, M.; Maciewicz, R.A.; Zhang, W.; Doherty, M. Osteoarthritis—Genetic studies of monogenic and complex forms. In Genetics of Bone Biology and Skeletal Disease; Thakker, R.V., Whyte, M.P., Eisman, J., Igarashi, T., Eds.; Elsevier: Waltham, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Valdes, A.M.; Spector, T.D. Genetic epidemiology of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2011, 7, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risch, N. Linkage strategies for genetically complex traits. II. The power of affected relative pairs. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1990, 46, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thomas, D.; Young, A.; Gorsuch, A.; Bottazzo, G.; Cudworth, A. Evidence for an association between rheumatoid arthritis and autoimmune endocrine disease. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1983, 42, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Del Junco, D.J.; Luthra, H.S.; Annegers, J.F.; Worthington, J.W.; Kurland, L.T. The familial aggregation of rheumatoid arthritis and its relationship to the HLA-DR4 association. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1984, 119, 813–829. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Seldin, M.F.; Amos, C.I.; Ward, R.; Gregersen, P.K. The genetics revolution and the assault on rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1999, 42, 1071–1079. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vyse, T.J.; Todd, J.A. Genetic analysis of autoimmune disease. Cell 1996, 85, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wordsworth, P. Genes and arthritis. Br. Med. Bull. 1995, 51, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Risch, N. Linkage strategies for genetically complex traits. I. Multilocus models. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1990, 46, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rich, S.S. Mapping genes in diabetes. Genetic epidemiological perspective. Diabetes 1990, 39, 1315–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacGregor, A.J.; Antoniades, L.; Matson, M.; Andrew, T.; Spector, T.D. The genetic contribution to radiographic hip osteoarthritis in women: Results of a classic twin study. Arthritis Rheum. 2000, 43, 2410–2416. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Williams, F.M.; Spector, T.D.; MacGregor, A.J. Pain reporting at different body sites is explained by a single underlying genetic factor. Rheumatology 2010, 49, 1753–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, G.; Ding, C.; Stankovich, J.; Cicuttini, F.; Jones, G. The genetic contribution to longitudinal changes in knee structure and muscle strength: A sibpair study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 52, 2830–2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, G.; Hart, D.J.; Kato, B.S.; MacGregor, A.; Spector, T.D. Genetic influence on the progression of radiographic knee osteoarthritis: A longitudinal twin study. Osteoarthrs. Cartil. 2007, 15, 222–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, A.E.; Smith, M.W.; Golightly, Y.M.; Jordan, J.M. “Generalized osteoarthritis”: A systematic review. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2014, 43, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felson, D.T.; Couropmitree, N.N.; Chaisson, C.E.; Hannan, M.T.; Zhang, Y.; McAlindon, T.E.; LaValley, M.; Levy, D.; Myers, R.H. Evidence for a mendelian gene in a segregation analysis of generalized radiographic osteoarthritis: The framingham study. Arthritis Rheum. 1998, 41, 1064–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, G.; Stankovich, J.; Ding, C.; Scott, F.; Cicuttini, F.; Jones, G. The genetic contribution to muscle strength, knee pain, cartilage volume, bone size, and radiographic osteoarthritis: A sibpair study. Arthritis Rheum. 2004, 50, 805–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syddall, C.M.; Reynard, L.N.; Young, D.A.; Loughlin, J. The identification of trans-acting factors that regulate the expression of GDF5 via the osteoarthritis susceptibility SNP rs143383. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Yao, J.; Xu, P.; Ji, B.; Luck, J.V.; Chin, B.; Lu, S.; Kelsoe, J.R.; Ma, J. A comprehensive meta-analysis of association between genetic variants of GDF5 and osteoarthritis of the knee, hip and hand. Inflamm. Res. 2015, 64, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyamoto, Y.; Mabuchi, A.; Shi, D.; Kubo, T.; Takatori, Y.; Saito, S.; Fujioka, M.; Sudo, A.; Uchida, A.; Yamamoto, S. A functional polymorphism in the 5′ UTR of GDF5 is associated with susceptibility to osteoarthritis. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdes, A.M.; Evangelou, E.; Kerkhof, H.J.M.; Tamm, A.; Doherty, S.A.; Kisand, K.; Tamm, A.; Kerna, I.; Uitterlinden, A.; Hofman, A.; et al. The GDF5 rs143383 polymorphism is associated with osteoarthritis of the knee with genome-wide statistical significance. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011, 70, 873–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, K.; Takahashi, A.; Meulenbelt, I.; Watson, C.; Rodriguez-Lopez, J.; Egli, R.; Tsezou, A.; Malizos, K.N.; Kloppenburg, M.; Shi, D.; et al. A meta-analysis of European and Asian cohorts reveals a global role of a functional SNP in the 5′ UTR of GDF5 with osteoarthritis susceptibility. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008, 17, 1497–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kizawa, H.; Kou, I.; Iida, A.; Sudo, A.; Miyamoto, Y.; Fukuda, A.; Mabuchi, A.; Kotani, A.; Kawakami, A.; Yamamoto, S.; et al. An aspartic acid repeat polymorphism in asporin inhibits chondrogenesis and increases susceptibility to osteoarthritis. Nat. Genet. 2005, 37, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdes, A.M.; Spector, T.D.; Tamm, A.; Kisand, K.; Doherty, S.A.; Dennison, E.M.; Mangino, M.; Tamm, A.; Kerna, I.; Hart, D.J.; et al. Genetic variation in the SMAD3 gene is associated with hip and knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 62, 2347–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Fontenla, C.; Calaza, M.; Evangelou, E.; Valdes, A.M.; Arden, N.; Blanco, F.J.; Carr, A.; Chapman, K.; Deloukas, P.; Doherty, M.; et al. Assessment of osteoarthritis candidate genes in a meta-analysis of nine genome-wide association studies. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014, 66, 940–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Loughlin, J. Genetic contribution to osteoarthritis development: Current state of evidence. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2015, 27, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, Y.F.; Meulenbelt, I. Implementation of functional genomics for bench-to-bedside transition in osteoarthritis. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2015, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioannidis, J. Calibration of credibility of agnostic genome-wide associations. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2008, 147, 964–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College of Rheumatology Pain Management Task Force. Report of the american college of rheumatology pain management task force. Arthritis Care Res. 2010, 62, 590–599. [Google Scholar]

- Hannan, M.T.; Felson, D.T.; Pincus, T. Analysis of the discordance between radiographic changes and knee pain in osteoarthritis of the knee. J. Rheumatol. 2000, 27, 1513–1517. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ayis, S.; Dieppe, P. The natural history of disability and its determinants in adults with lower limb musculoskeletal pain. J. Rheumatol. 2009, 36, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diatchenko, L.; Nackley, A.G.; Tchivileva, I.E.; Shabalina, S.A.; Maixner, W. Genetic architecture of human pain perception. Trends Genet. 2007, 23, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diatchenko, L.; Slade, G.D.; Nackley, A.G.; Bhalang, K.; Sigurdsson, A.; Belfer, I.; Goldman, D.; Xu, K.; Shabalina, S.A.; Shagin, D.; et al. Genetic basis for individual variations in pain perception and the development of a chronic pain condition. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005, 14, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, K.; Clauw, D.J. Central pain mechanisms in the rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2013, 65, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Meurs, J.B.J.; Uitterlinden, A.G.; Stolk, L.; Kerkhof, H.J.M.; Hofman, A.; Pols, H.A.P.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.A. A functional polymorphism in the catechol-O-methyltransferase gene is associated with osteoarthritis-related pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 60, 628–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neogi, T.; Soni, A.; Doherty, S.; Laslett, L.; Maciewicz, R.; Hart, D.; Zhang, W.; Muir, K.; Wheeler, M.; Cooper, C. Contribution of the COMT Val158Met variant to symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014, 73, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdes, A.M.; Arden, N.K.; Vaughn, F.L.; Doherty, S.A.; Leaverton, P.E.; Zhang, W.; Muir, K.R.; Rampersaud, E.; Dennison, E.M.; Edwards, M.H.; et al. Role of the NAv1.7 R1150W amino acid change in susceptibility to symptomatic knee osteoarthritis and multiple regional pain. Arthritis Care Res. 2011, 63, 440–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdes, A.M.; de Wilde, G.; Doherty, S.A.; Lories, R.J.; Vaughn, F.L.; Laslett, L.L.; Maciewicz, R.A.; Soni, A.; Hart, D.J.; Zhang, W.; et al. The Ile585Val TRPV1 variant is involved in risk of painful knee osteoarthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011, 70, 1556–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malfait, A.M.; Seymour, A.B.; Gao, F.; Tortorella, M.D.; le Graverand-Gastineau, M.P.H.; Wood, L.S.; Doherty, M.; Doherty, S.; Zhang, W.; Arden, N.K.; et al. A role for PACE4 in osteoarthritis pain: Evidence from human genetic association and null mutant phenotype. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2012, 71, 1042–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, F.S.; Morgan, M.; Patrinos, A. The human genome project: Lessons from large-scale biology. Science 2003, 300, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorde, L.B.; Carey, C.J.; Bamshad, M.J.; White, R.L. Medical Genetics, 3rd ed.; Mosby: St. Louis, MI, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- International HapMap 3 Consortium. Integrating common and rare genetic variation in diverse human populations. Nature 2010, 467, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima, M.; Takahashi, A.; Kou, I.; Rodriguez-Fontenla, C.; Gomez-Reino, J.J.; Furuichi, T.; Dai, J.; Sudo, A.; Uchida, A.; Fukui, N. New sequence variants in HLA class II/III region associated with susceptibility to knee osteoarthritis identified by genome-wide association study. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evangelou, E.; Valdes, A.M.; Kerkhof, H.J.; Styrkarsdottir, U.; Zhu, Y.; Meulenbelt, I.; Lories, R.J.; Karassa, F.B.; Tylzanowski, P.; Bos, S.D.; et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies confirms a susceptibility locus for knee osteoarthritis on chromosome 7q22. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011, 70, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day-Williams, A.G.; Southam, L.; Panoutsopoulou, K.; Rayner, N.W.; Esko, T.; Estrada, K.; Helgadottir, H.T.; Hofman, A.; Ingvarsson, T.; Jonsson, H.; et al. A variant in MCF2L is associated with osteoarthritis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011, 89, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Evangelou, E.; Kerkhof, H.J.; Styrkarsdottir, U.; Ntzani, E.E.; Bos, S.D.; Esko, T.; Evans, D.S.; Metrustry, S.; Panoutsopoulou, K.; Ramos, Y.F.; et al. A meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies novel variants associated with osteoarthritis of the hip. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014, 73, 2130–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Evans, D.S.; Cailotto, F.; Parimi, N.; Valdes, A.M.; Castaño-Betancourt, M.C.; Liu, Y.; Kaplan, R.C.; Bidlingmaier, M.; Vasan, R.S.; Teumer, A. Genome-wide association and functional studies identify a role for IGFBP3 in hip osteoarthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2015, 74, 1861–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evangelou, E.; Valdes, A.M.; Castano-Betancourt, M.C.; Doherty, M.; Doherty, S.; Esko, T.; Ingvarsson, T.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Kloppenburg, M.; Metspalu, A.; et al. The DOT1L rs12982744 polymorphism is associated with osteoarthritis of the hip with genome-wide statistical significance in males. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2013, 72, 1264–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdes, A.M.; Loughlin, J.; Timms, K.M.; van Meurs, J.J.B.; Southam, L.; Wilson, S.G.; Doherty, S.; Lories, R.J.; Luyten, F.P.; Gutin, A.; et al. Genome-wide association scan identifies a prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 variant involved in risk of knee osteoarthritis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008, 82, 1231–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, D.; Zheng, Q.; Chen, D.; Zhu, L.; Qin, A.; Fan, J.; Liao, J.; Xu, Z.; Lin, Z.; Norman, P. Association of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in HLA class II/III region with knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2010, 18, 1454–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdes, A.M.; Styrkarsdottir, U.; Doherty, M.; Morris, D.L.; Mangino, M.; Tamm, A.; Doherty, S.A.; Kisand, K.; Kerna, I.; Tamm, A.; et al. Large scale replication study of the association between HLA class II/BTNL2 variants and osteoarthritis of the knee in European-descent populations. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, W.; Dolan, M.E. Impact of the 1000 genomes project on the next wave of pharmacogenomic discovery. Pharmacogenomics 2010, 11, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, N.E.; Schnitzer, T.J.; Birbara, C.A.; Mokhtarani, M.; Shelton, D.L.; Smith, M.D.; Brown, M.T. Tanezumab for the treatment of pain from osteoarthritis of the knee. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 1521–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panoutsopoulou, K.; Metrustry, S.; Doherty, S.A.; Laslett, L.L.; Maciewicz, R.A.; Hart, D.J.; Zhang, W.; Muir, K.R.; Wheeler, M.; Cooper, C.; et al. The effect of FTO variation on increased osteoarthritis risk is mediated through body mass index: A mendelian randomisation study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014, 73, 2082–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castaño Betancourt, M.C.; Cailotto, F.; Kerkhof, H.J.; Cornelis, F.M.F.; Doherty, S.A.; Hart, D.J.; Hofman, A.; Luyten, F.P.; Maciewicz, R.A.; Mangino, M.; et al. Genome-wide association and functional studies identify the DOT1L gene to be involved in cartilage thickness and hip osteoarthritis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 8218–8223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerkhof, H.J.; Meulenbelt, I.; Akune, T.; Arden, N.K.; Aromaa, A.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.; Carr, A.; Cooper, C.; Dai, J.; Doherty, M. Recommendations for standardization and phenotype definitions in genetic studies of osteoarthritis: The treat-OA consortium. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2011, 19, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ratnayake, M.; Ploger, F.; Santibanez-Koref, M.; Loughlin, J. Human chondrocytes respond discordantly to the protein encoded by the osteoarthritis susceptibility gene GDF5. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86590. [Google Scholar]

- Dodd, A.W.; Syddall, C.M.; Loughlin, J. A rare variant in the osteoarthritis-associated locus GDF5 is functional and reveals a site that can be manipulated to modulate GDF5 expression. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2013, 21, 517–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daans, M.; Luyten, F.P.; Lories, R.J. GDF5 deficiency in mice is associated with instability-driven joint damage, gait and subchondral bone changes. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011, 70, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynard, L.N.; Bui, C.; Syddall, C.M.; Loughlin, J. CpG methylation regulates allelic expression of GDF5 by modulating binding of SP1 and SP3 repressor proteins to the osteoarthritis susceptibility SNP rs143383. Hum. Genet. 2014, 133, 1059–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raine, E.V.; Dodd, A.W.; Reynard, L.N.; Loughlin, J. Allelic expression analysis of the osteoarthritis susceptibility gene COL11A1 in human joint tissues. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2013, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gee, F.; Clubbs, C.F.; Raine, E.V.; Reynard, L.N.; Loughlin, J. Allelic expression analysis of the osteoarthritis susceptibility locus that maps to chromosome 3p21 reveals cis-acting eQTLs at GNL3 and SPCS1. BMC Med. Genet. 2014, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raine, E.V.; Wreglesworth, N.; Dodd, A.W.; Reynard, L.N.; Loughlin, J. Gene expression analysis reveals HBP1 as a key target for the osteoarthritis susceptibility locus that maps to chromosome 7q22. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2012, 71, 2020–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, K.; Reynard, L.N.; Loughlin, J. Functional characterisation of the osteoarthritis susceptibility locus at chromosome 6q14.1 marked by the polymorphism rs9350591. BMC Med. Genet. 2015, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdes, A.M.; Doherty, S.A.; Muir, K.R.; Wheeler, M.; Maciewicz, R.A.; Zhang, W.; Doherty, M. The genetic contribution to severe post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2013, 72, 1687–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerkhof, H.J.M.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.A.; Arden, N.K.; Metrustry, S.; Castano-Betancourt, M.; Hart, D.J.; Hofman, A.; Rivadeneira, F.; Oei, E.H.G.; Spector, T.D.; et al. Prediction model for knee osteoarthritis incidence, including clinical, genetic and biochemical risk factors. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014, 73, 2116–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karsdal, M.A.; Bay-Jensen, A.C.; Lories, R.J.; Abramson, S.; Spector, T.; Pastoureau, P.; Christiansen, C.; Attur, M.; Henriksen, K.; Goldring, S.R.; et al. The coupling of bone and cartilage turnover in osteoarthritis: Opportunities for bone antiresorptives and anabolics as potential treatments? Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014, 73, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Trait | Heritability (h2) | Type of Study | Data from Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radiographic knee Osteoarthritis (OA) | 39% | Twins | [14] |

| Radiographic hip OA | 60% | Twins | [27] |

| Generalised OA | 42% | Spouse pairs, Parent-child pairs, Sibling pairs | [31,32] |

| Knee pain reporting | 44%–46% | Twins | [28,29] |

| Radiographic progression | 69% | Twins | [30] |

| Cartilage volume | 77%–85% | Sibling pairs | [33] |

| Changes lower limb in muscle strength | 64% | Sibling pairs | [29] |

| SNP ID | Gene | Ethnic Group | Trait | Total Sample Size | p-value | Putative or Known Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs11718863 | DVWA | Asians | Knee OA | 982 cases, 1774 controls | 7 × 10−11 | Cartilage-specific tubulin binding | [8] |

| rs11177/rs6976 * | GLN3/GLT8D1 | Caucasians | Hip or knee OA | 14,883 cases, 53,947 controls | 7 × 10−11 | Cell cycle control, tumorigenesis and cellular senescence | [6] |

| rs4836732 | ASTN2 | Caucasians | Total hip replacement (THR) | 5813 cases, 53,947 controls | 6.1 × 10−10 | Glial neuronal migration | [6] |

| rs9350591 | FILIP1/SENP6 | Caucasians | THR | 5813 cases, 53,947 controls | 2 × 10−9 | Various genes | [6] |

| rs10947262 | BTNL2 | Asians | Knee OA | 906 cases, 3396 controls | 5 × 10−9 | Immunomodulatory function, T-cell response | [59] |

| rs4730250 | COG5/GPR22/DUS4L/HBP1 | Caucasians | Knee OA | 6709 cases, 44,439 controls | 9 × 10−9 | Various genes (see [60]) | [60] |

| rs11842874 | MCF2L | Caucasians | Knee or hip OA | 19,041 cases, 24,504 controls | 2 × 10−8 | Cell motility | [61] |

| rs10492367 | PTHLH | Caucasians | Hip OA | 6329 cases, 53,947 controls | 1.5 × 10−8 | Chondrogenic regulator | [6] |

| rs835487 | CHST11 | Caucasians | THR | 5813 cases, 53,947 controls | 2 × 10−8 | Chondroitin sulfotransferase involved in cartilage metabolism | [6] |

| rs7775228 | HLA–DQB1 | Asians | Knee OA | 906 cases, 3396 controls | 2 × 10−8 | Immune response (antigen presentation) | [59] |

| rs12107036 | TP63 | Caucasians | Total knee replacement (TKR) in women | 4085 cases, 33,587 controls | 7 × 10−8 | Member of the p53 family of transcription factors | [6] |

| rs8044769 | Fat mass and obesity-associated (FTO) | Caucasians | TKR in women | 4085 cases, 33,587 controls | 7 × 10−8 | Control of energy homeostasis | [6] |

| rs10948172 | SUPT3H/RUNX2 | Caucasians | OA (hip or knee) in men | 5617 cases, 20,360 controls | 8 × 10−8 | Probable transcriptional activator | [6] |

| rs6094710 | NCOA3 | Caucasians | Hip OA | 11,277 cases, 67,473 controls | 7.9 × 10−9 | Nuclear receptor | [62] |

| rs788748 | IGFBP3 | Caucasians | Hip OA | 3243 cases, 6891 controls | 2 × 10−8 | Cartilage catabolism and osteogenic differentiation | [63] |

| rs12982744 | DOT1L | Caucasians | Hip OA | 9789 cases, 31,873 controls | 8.1 × 10−8 | Wnt signalling | [64] |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Warner, S.C.; Valdes, A.M. The Genetics of Osteoarthritis: A Review. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2016, 1, 140-153. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk1010140

Warner SC, Valdes AM. The Genetics of Osteoarthritis: A Review. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2016; 1(1):140-153. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk1010140

Chicago/Turabian StyleWarner, Sophie Catriona, and Ana Maria Valdes. 2016. "The Genetics of Osteoarthritis: A Review" Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 1, no. 1: 140-153. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk1010140