Impact of Sweet Potato Starch-Based Nanocomposite Films Activated With Thyme Essential Oil on the Shelf-Life of Baby Spinach Leaves

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains

2.2. Antibacterial Activity of Thyme Essential Oil

2.3. Preparation of SPS/Clay-TEO Solution

2.4. Preparation of Nanocomposite Films

2.5. Antibacterial Activity of the Film

2.6. Antimicrobial Effects of Films on Inoculated Baby Spinach Leaves During Refrigerated Storage

2.6.1. Baby Spinach Leaves Preparation

2.6.2. Microbiological Analysis of Spinach Samples

2.7. Sensory Evaluation of Baby Spinach Leaves

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

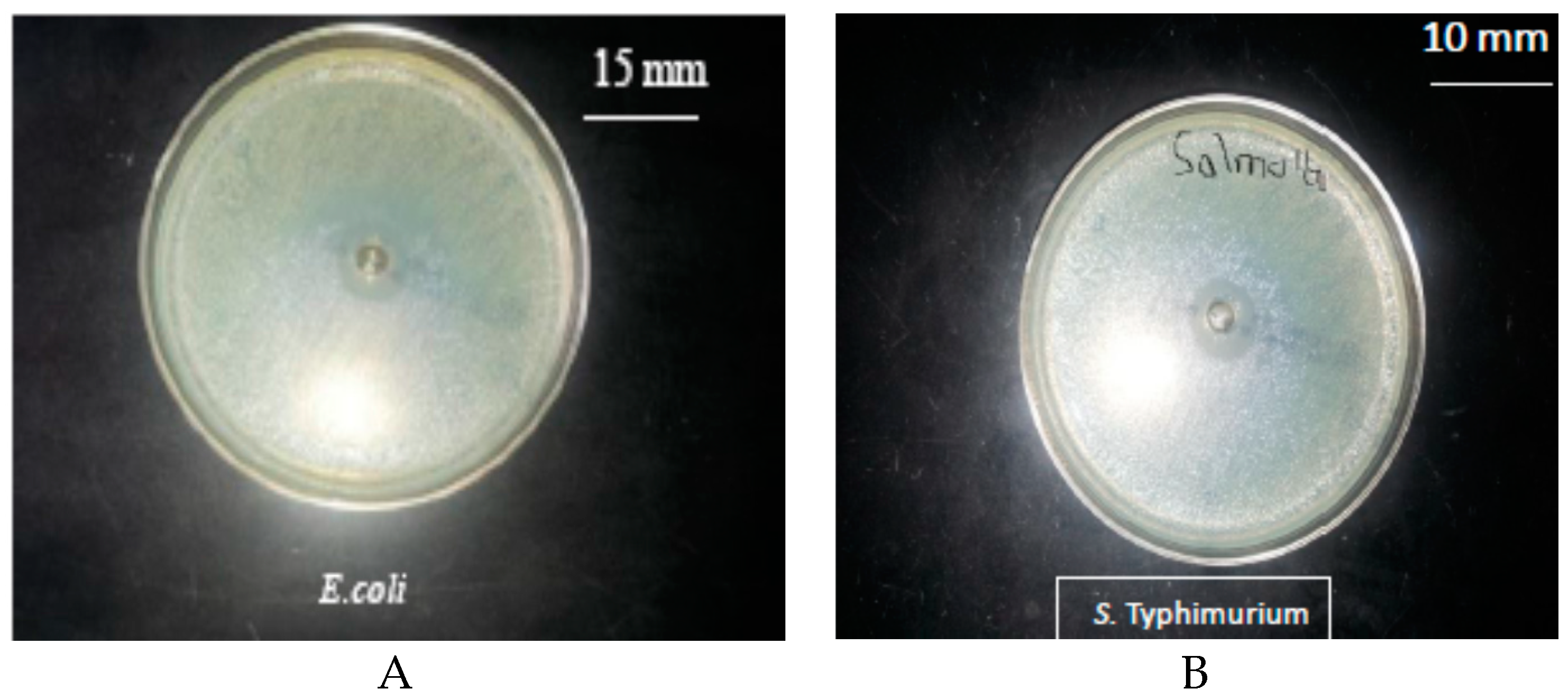

3.1. Antimicrobial Activity of the Pure Thyme Essential Oil

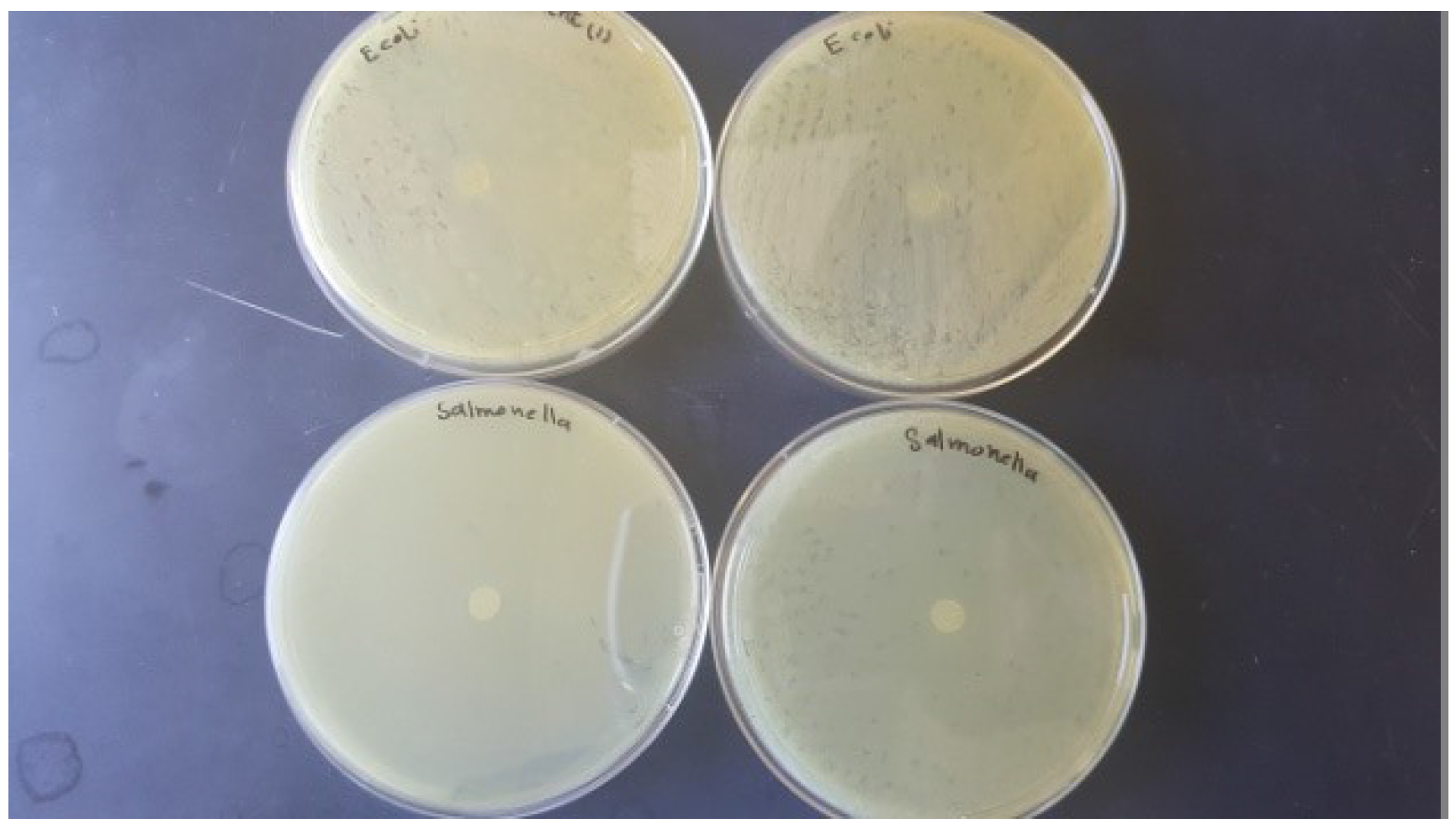

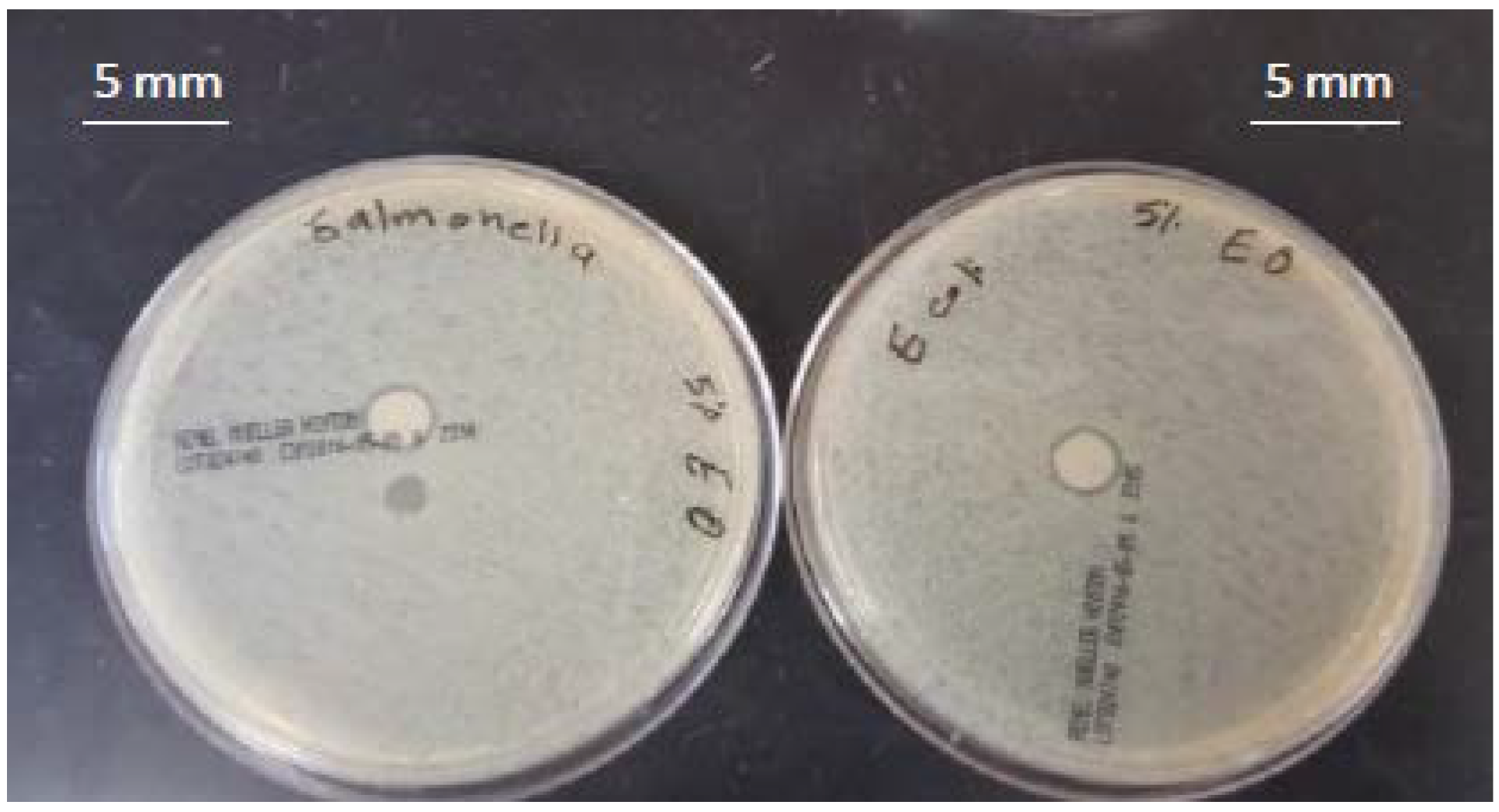

3.2. Antimicrobial Activity of Films

3.3. The Effect of Films on Total Viable Count, Yeast and Mold Growth of Baby Spinach Leaves

3.4. The Antibacterial Effect of the Films on Baby Spinach Leaves Inoculated with E. coli and S. Typhimurium

3.5. Sensory Evaluation of Baby Spinach Leaves

4. Discussion

4.1. Antimicrobial Activity of Pure Thyme Essential Oil

4.2. Antimicrobial Activity of the Films

4.3. The Effect of Films on Total Viable Count, Yeast and Mold Growth of Baby Spinach Leaves

4.4. The Antibacterial Effect of Films on Baby Spinach Leaves Inoculated with E. coli and S. Typhimurim

4.5. Sensory Evaluation of Baby Spinach Leaves

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Su, L.J.; Arab, L. Salad and raw vegetable consumption and nutritional status in the adult US population: Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2006, 106, 1394–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warriner, K.; Huber, A.; Namvar, A.; Fan, W.; Dunfield, K. Recent advances in the microbial safety of fresh fruits and vegetables. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2009, 57, 155–208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Guidance for Industry: Guide to Minimize Microbial Food Safety Hazards of Leafy Greens. 2009. Available online: http://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/GuidanceDocuments/ProduceandPlanProducts/ucm174200.htm#intro (accessed on 25 April 2017).

- Jacxsens, L.; Devlieghere, F.; Van der Steen, C.; Debevere, J. Effect of high oxygen modified atmosphere packaging on packaging on microbial growth and sensorial qualities of fresh-cut produce. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2001, 71, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, K.; Bugusu, B. Food Packaging–Roles, Materials, and Environmental Issues. J. Food Sci. 2007, 72, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Rosas, J.; Cruz-Galvez, A.M.; Gomez-Aldapa, C.A.; Falfan-Cortes, R.N.; Guzman-Ortiz, F.A.; Rodríguez-Marín, M.L. Biopolymer films and the effects of added lipids, nanoparticles and antimicrobials on their mechanical and barrier properties: A review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 51, 1967–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battis, F.; Pineau, F.; Popineau, Y.; Aparicio, C.; Kanny, G.; Guerin, L.; Moneret-Vautrin, D.A.; Denery-Papini, S. Food allergy to wheat: Identification of immunogloglin E and immunoglobulin G-binding proteins with sequential extracts and purified proteins from wheat flour. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2003, 33, 962–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordle, C.T. Soy Protein Allergy: Incidence and Relative Severity. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 1213–1219. [Google Scholar]

- Bu, G.; Luo, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Zheng, H. Effect of heat treatment on the antigenicity of bovine α-lactalbumin and β-lactoglobulin in whey protein isolate. Food Agric. Immunol. 2009, 20, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertuzzi, M.A.; Armada, M.; Gottifredi, J.C. Physicochemical characterization of starch based films. J. Food Eng. 2007, 82, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.L.; Wu, J.M.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, G. Antimicrobial and physical properties of sweet potato starch films incorporated with potassium sorbate or chitosan. Food Hydrocoll. 2010, 24, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, A.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Tahergorabi, R. Sweet potato starch/clay nanocomposite film: New material for emerging biodegradable food packaging. MOJ Food Process. Technol. 2016, 3, 00073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlashan, S.A.; Halley, P.J. Preparation and characterization of biodegradable starch-based nanocomposite materials. Polym. Int. 2003, 52, 1767–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Rozas, J.; Haynie, D.T. Structural stability of polypeptide nanofilms under extreme conditions. Biotechnol. Prog. 2006, 22, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, B.K.; Valdramidis, V.P.; Donnell, C.P.O.; Muthukumarappan, K.; Bourke, P.; Cullen, P.J. Application of Natural Antimicrobials for Food Preservation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 5987–6000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, M. Characterization of Allergenic and Antimicrobial Properties of Chitin and Chitosan and Formulation of Chitosan-Based Edible Film for Instant Food Casing. Ph.D. Thesis, Applied Sciences, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia, March 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, N.; Sing, R.K.; Bhunia, A.K. Sequential disinfection of Escherichia coli O157:H7 inoculated alfalfa seeds before and during sprouting using aqueous chlorine dioxide, ozonated water, and thyme essential oil. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2003, 36, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagamboula, C.F.; Uyttendaele, M.; Debevere, J. Inhibitory effect of thyme and basil essential oils, carvacrol, thymol, estragol, linalool and p-cymene towards Shigella sonnei and S. flexneri. Food Microbiol. 2004, 21, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, S. Essential oils: Their antibacterial properties and potential applications in foods—A review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004, 94, 223–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Estaca, J.; De Lacey, A.L.; López-Caballero, M.E.; Gómez-Guillén, M.C.; Montero, P. Biodegradable gelatin–chitosan films incorporated with essential oils as antimicrobial agents for fish preservation. Food Microbiol. 2010, 27, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seydim, A.C.; Sarikus, G. Antimicrobial activity of whey protein based edible films incorporated with oregano, rosemary and garlic essential oils. Food Res. Int. 2006, 39, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, B.S.M.; Linton, R.H. Inactivation kinetics of inoculated Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Salmonella enterica on lettuce by chlorine dioxide gas. Food Microbiol. 2008, 25, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentin-Bon, I.; Jacobson, A.; Monday, S.R.; Feng, P.C. Microbiological quality of bagged cut spinach and lettuce mixes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 1240–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez Calleja, J.M.; Cruz-Romero, M.C.; García-López, M.L.; Kerry, J.P. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of commercially available essential oils and their oleoresins. J. Herb. Sci. 2015, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Rota, M.C.; Herrera, A.; Martínez, R.M.; Sotomayor, J.A.; Jordán, M.J. Antimicrobial activity and chemical composition of Thymus vulgaris, Thymus zygis and Thymus hyemalis essential oils. Food Control 2008, 19, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consentino, S.; Tuberoso, C.I.G.; Pisano, B.; Satta, M.; Arzedi, E.; Palmas, F. In vitro antimicrobial activity and chemical composition of sardinian Thymus essential oils. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 1999, 29, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, P.M.; Naidu, A.S. Phyto-Phenol in Natural Food Antimicrobial Systems; Naidu, A.S, Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2000; pp. 265–294. [Google Scholar]

- Skocibusic, M.; Bezic, N.; Dunkic, V. Phytochemical composition and antimicrobial activities of essential oils from Satureja subspicata Vis. growing in Croatia. Food Chem. 2006, 96, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, M.; Rezaei, M.; Farzi, G. A novel active bionanocomposite film incorporating rosemary essential oil and nanoclay into chitosan. J. Food Eng. 2012, 111, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.H.; Razavi, S.H.; Mousavi, M.A. Antimicrobial, physical and mechanical properties of chitosan-based films incorporated with thyme, clove and cinnamon essential oils. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2009, 33, 727–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila-Sosa, R.; Palou, E.; Munguía, M.T.J.; Nevárez-Moorillón, G.V.; Cruz, A.R.N.; López-Malo, A. Antifungal activity by vapor contact of essential oils added to amaranth, chitosan, or starch edible films. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 153, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valderrama, N.; Albarracín, W.; Algecira, N. Physical and Microbiological Evaluation of Chitosan Films: Effect of Essential Oils and Storage. World Acad. Sci. Eng. Technol. Int. J. Chem. Mol. Nucl. Mater. Metall. Eng. 2015, 9, 262–269. [Google Scholar]

- Zivanovic, S.; Chi, S.; Draughon, A.F. Antimicrobial activity of chitosan films enriched with essential oils. J. Food Sci. 2005, 70, M45–M51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harpaz, S.; Glatman, L.; Drabkin, V.; Gelman, A. Effects of herbal essential oils used to extend the shelf life of freshwater-reared Asian sea bass fish (Lates calcarifer). J. Food Prot. 2003, 66, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goni, P.; López, P.; Sánchez, C.; Gómez-Lus, R.; Becerril, R.; Nerín, C. Antimicrobial activity in the vapour phase of a combination of cinnamon and clove essential oils. Food Chem. 2009, 116, 982–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawless, H.T.; Heymann, H. Sensory Evaluation of Food: Principles and Practices, 1st ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Meilgaard, M.; Civille, G.V.; Carr, B.T. Sensory Evaluation Techniques, 4th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

| Treatment | MMT (%) | TEO (%) | Inhibition Zone (mm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | S. Typhymurium | |||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| 5 | 3 | 6 | 10 | 7 |

| Day | Microorganisms | Unwrapped | Treatment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| Log Colony Forming Unit (CFU)/g | |||||||

| Day 2 | TVC | 2.80 | 2.50 | 2.34 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.69 |

| Yeast/Mold | 1.70 | 1.63 | 0.5 | ND | ND | ND | |

| Day 8 | TVC | 3.00 | 2.04 | 1.00 | ND | ND | ND |

| Yeast/Mold | 1.80 | 1.75 | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Treatment | Microorganism | Log CFU/g | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 2 | Day 4 | Day 6 | Day 8 | |||

| 1 | E. coli | Unwrapped | 1.60 | 1.60 | 2.47 | 3.00 |

| wrapped | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.15 | 1.10 | ||

| Salmonella | Unwrapped | 2.04 | 2.95 | 2.25 | 6.80 | |

| wrapped | 1.08 | ND | ND | ND | ||

| 2 | E. coli | Unwrapped | 2.00 | 2.90 | 3.60 | 3.75 |

| wrapped | 1.30 | ND | ND | ND | ||

| Salmonella | Unwrapped | 1.69 | 2.60 | 2.80 | 3.00 | |

| wrapped | 1.60 | 1.00 | ND | ND | ||

| 3 | E. coli | Unwrapped | 2.07 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 4.30 |

| wrapped | 1.30 | ND | DN | DN | ||

| Salmonella | Unwrapped | 1.30 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 3.69 | |

| wrapped | DN | DN | DN | DN | ||

| 4 | E. coli | Unwrapped | 2.84 | 2.90 | 3.00 | 3.00 |

| wrapped | DN | DN | DN | DN | ||

| Salmonella | Unwrapped | 2.84 | 3.23 | 3.96 | 4.30 | |

| wrapped | DN | DN | DN | DN | ||

| 5 | E. coli | Unwrapped | 2.90 | 2.95 | 3.07 | 4.84 |

| wrapped | DN | ND | DN | DN | ||

| Salmonella | Unwrapped | 2.30 | 2.47 | 4.00 | 4.90 | |

| wrapped | ND | ND | DN | DN | ||

| Days | Unwrapped | Treatment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| color | ||||||

| 1 | 8.0 ± 0.00 a | 8.0 ± 0.00 a | 8.0 ± 0.00 a | 9.0 ± 1.00 a | 8.0 ± 0.00 a | 8.5± 0.70 a |

| 8 | 7.0 ± 0.01 a | 7.0 ± 0.03 a | 7.0 ± 0.82 a | 7.0 ± 0.96 a | 7.0 ± 0.5 a | 7.5 ± 0.58 a |

| Odor | ||||||

| 1 | 7.0 ± 0.02 a | 7.5 ± 0.00 a | 7.5 ± 0.00 a | 8.0 ± 0.50 a | 8.0 ± 0.70 a | 8.0 ± 0.70 a |

| 8 | 7.0 ± 0.01 a | 7.0 ± 0.00 a | 7.0 ± 0.00 a | 7.0 ± 0.00 a | 7.5 ± 0.70 a | 7.5 ± 0.70 a |

| Overall appearance | ||||||

| 1 | 8.0 ± 0.00 a | 8.0 ± 0.01 a | 8.0 ± 0.00 a | 8.0 ± 0.01 a | 8.5 ± 0.05 a | 8.0 ± 0.04 a |

| 8 | 8.0 ± 0.00 a | 7.0 ± 0.00 a | 7.0 ± 0.00 a | 8.0 ± 0.00 a | 8.0 ± 0.70 a | 8.5 ± 0.70 a |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Issa, A.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Tahergorabi, R. Impact of Sweet Potato Starch-Based Nanocomposite Films Activated With Thyme Essential Oil on the Shelf-Life of Baby Spinach Leaves. Foods 2017, 6, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods6060043

Issa A, Ibrahim SA, Tahergorabi R. Impact of Sweet Potato Starch-Based Nanocomposite Films Activated With Thyme Essential Oil on the Shelf-Life of Baby Spinach Leaves. Foods. 2017; 6(6):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods6060043

Chicago/Turabian StyleIssa, Aseel, Salam A. Ibrahim, and Reza Tahergorabi. 2017. "Impact of Sweet Potato Starch-Based Nanocomposite Films Activated With Thyme Essential Oil on the Shelf-Life of Baby Spinach Leaves" Foods 6, no. 6: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods6060043