“That Guy, Is He Really Sick at All?” An Analysis of How Veterans with PTSD Experience Nature-Based Therapy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. PTSD Diagnosis and Prevalence among Veterans

1.2. How Living with PTSD Affects Veterans’ Lives

1.3. Conventional Treatments for Veterans with PTSD

1.4. How NBT Can Be Seen as Part of a Treatment for Veterans with PTSD

1.5. Nature-Based Therapy (NBT)

2. Materials and Methods

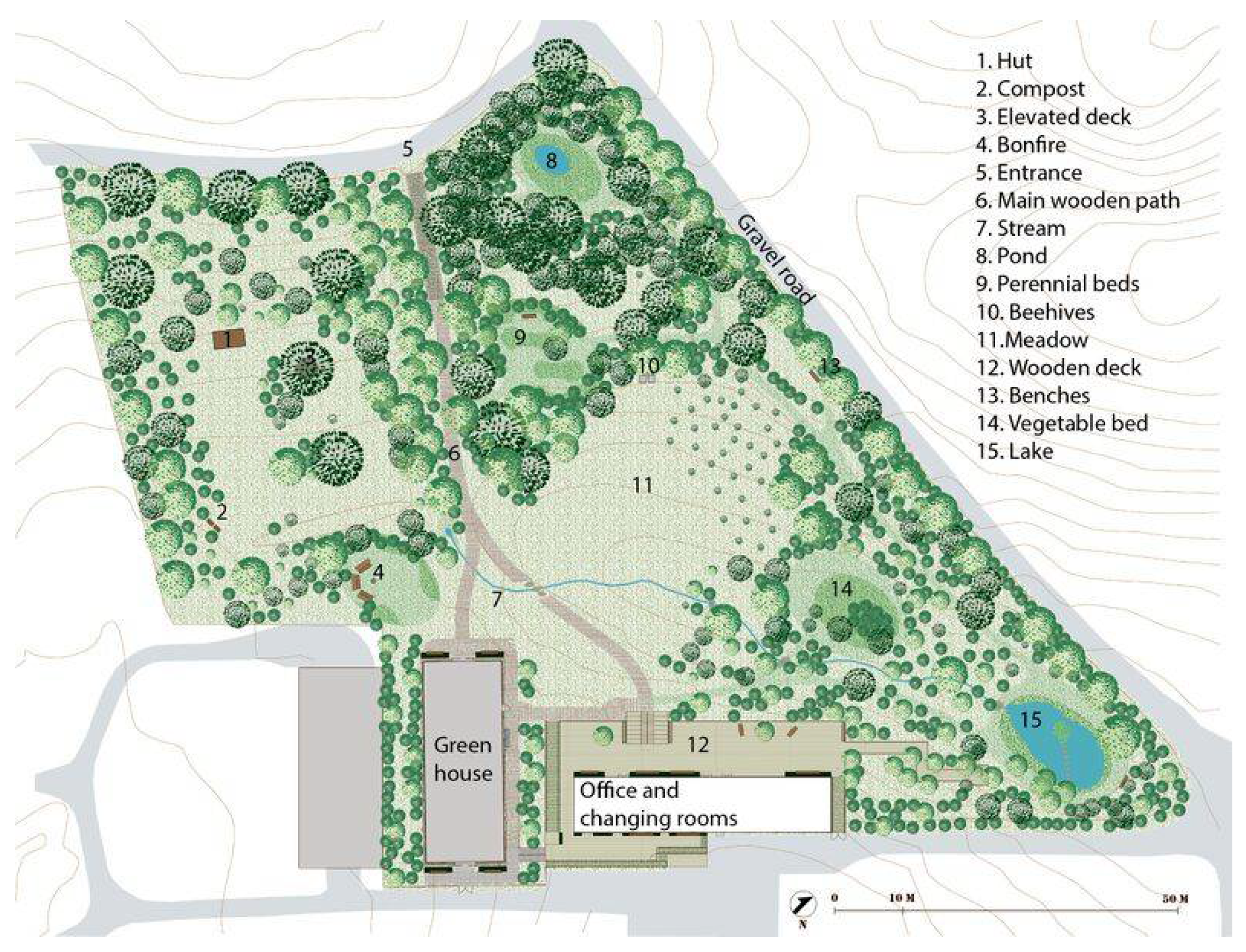

2.1. Setting

2.2. The Therapists

2.3. Nature-Based Therapy

2.4. Participants

2.5. Data Collection and Analysis

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. When the Body Speaks

“I was like a volcano; I felt the pressure inside and out. Suddenly it says BOOM. Sometimes I felt like I had to run as fast as I could to get away from myself.”

”First there’s a pressure on my chest, like a child pressing, then it tightens like a band round my trunk, and in the end, it’s like an elephant planting a foot on my chest, pressing so hard I can’t breathe.”

”I have struggled tremendously the last year to make them aware of my problems […] It has been the most stressful thing in my whole life. I just hope that I will be treated as I deserve.”

“My dreams… I have positive dreams now. I still have some of those dreams that are hard to handle, but I am more distanced from them. Like standing outside and looking down on it. It does not affect me in the same way. More relaxed, you can say.”

“All that yoga and stuff, I do it because I am looking forward to lying down and listening [] … I love to be in that trance-like state…I’m almost counting down.”

“I feel like the body is relaxing more. …normally I feel like a radar for people’s anger, even though it doesn’t have anything to do with me. If I go down the street and see someone who is angry, my system is up high [..]. Now I can tell myself it has nothing to do with me.”

3.2. Relationships, Imperative and Unbearable

“Your comrades are the ones you would die for…and the ones who help you handle your problems.”

“I feel guilty about being alive, and that I did not bring my comrade back home with me, even though I promised his mum I would.”

“That guy, is he really sick?”

“I haven’t got the room inside me to be there for her every day… I can’t… for me feelings are just not like before.”

“I look at her…her hands, if she is carrying something, keys or… or if something looks different. If her hand is closed, I have to follow her movements until I have seen what she has got there.”

“It has been terrible. Especially for my son. He has his needs… [interviewer: And you can`t give this to him?] “No, I can’t take it [touching and skin-contact].”

“It’s hard for me to express how I’m feeling and maybe also hard for them to know what to say to me [...] Not even my family knows much about how I’m doing. It stays inside me, and it’s very very hard to open up and talk about how I’m feeling and thinking.”

“If I had started in another group, where people had PTSD but for civil reasons, I don’t think it would have been the same… we have this mutual understanding [...] There are things we don’t need to say… we know what it’s like to serve abroad and be in a state of constant alertness.”

3.3. The Future, Dreams, Fears, and Hopes

“I need an instrument to control the turmoil and nerves in my body because I hate it. I hate having it […] it’s a heavy burden.”

“You get anxious of this change [of oneself]. And where does it lead to? You see the weirdo on the street, and suddenly you imagine that’s the way you’re going.”

“Future? It’s almost like it’s just some letters on a piece of paper that I see. A mathematical formula on a white wall…”

“Before, I was so preoccupied with saying, in six months I will have got so far with my disease. But I’ve dropped everything to do with time horizons and that sort of thing. Things must come as they are, the more I hurry, the more I stress myself, and the less energy I have to handle things.”

“Now I manage to do some of those things that I had completely avoided before […] Yes I have a dream…being more independent [financially] through having a job. Sometimes I really wonder if I am that damaged that it’s a utopia for me…but, then I think, if I really could make it, I would create a life together with my son.”

3.4. Identity—Construction of a Self

“Then my boss comes up to me and grabs me. I remember, I tried to get away, but then he gave me a hug. And then it starts! A tiny little spark… And then the priest comes over, and he’s a fucking good priest. He’s like a dad. He always blesses us when we go on patrol, and it might look silly on television, but it’s bloody important when you’re in a place like that.”

“Well it’s a bit strange, but when I was in the military, I was walking in the night, it was much more comfortable if I had my rifle, although it was secured and only fired blanks…it was still my weapon, and it gave me some calmness and protection […] and even when I walk around as a civilian, I miss it, walking at night.”

“I’m a stranger in the world, but also to my own body, and the only thing that ties me to the world is a sewing thread.”

“I’ve found out that I don’t even have the foundations of the house…you build up a little, and find out that it must be in another way because it doesn’t work for me that way.”

“It’s a place where I feel respected, and they talk to me as a human being and not just a worker, so I want to give more, and I can push myself more […] I’ve got my professional pride back.”

3.5. Lessons Learned, Reflections

“So I try to do different things…there’s a dog’s playground next to my place, and for a period, I sat on a bench nearby. Partly not to be too close, but on the other hand, I wanted to be so close that I got some human contact without being in focus.”

“One might think about things in a totally different way now, and it [the PTSD symptoms] makes you rise to the challenge, but at the same time, you become more handicapped…or what you might say.”

”I’ve found out that everything does not have to be exactly in order all the time, right? Before, it meant a great deal to me that everything was in the right place. I think it’s because I found out that my head can’t deal with it.”

“I was not the only one who felt that way,—but we are soldiers and follow orders [..]”

”I have changed now because I dare to say ‘no’, and it will be easier for me in my future life.”

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wise, J. Digging for Victory: Horticultural Therapy with Veterans for Post-Traumatic Growth; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, E.; Wessely, S. Battle for the Mind: World War 1 and the Birth of Military Psychiatry. Lancet 2014, 384, 1708–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chater, K. Exploring a Growing Field: Canadian Horticultural Therapy Organizations. Ph.D. Thesis, City University of Seattle, Seattle, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, C.; Christopher. The Origins, Development and Perceived Effectiveness of Horticulture-Based Therapy in Victoria. Ph.D. Thesis, Deakin Univeristy, Victoria, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dursa, E.K.; Reinhard, M.J.; Barth, S.K.; Schneiderman, A.I. Prevalence of a Positive Screen for PTSD among OEF/OIF and OEF/OIF-Era Veterans in a Large Population-Based Cohort. J. Trauma. Stress 2014, 27, 542–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFarlane, A.; Hodson, S.E. Mental Health in the Australian Defence Force: 2010 ADF Mental Health Prevalence and Wellbeing Study: Report; Department of Defence: Washington, DC, USA, 2011.

- Hoge, C.W.; Auchterlonie, J.L.; Milliken, C.S. Mental Health Problems, Use of Mental Health Services, and Attrition from Military Service after Returning from Deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA 2006, 295, 1023–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, L.K.; Frueh, B.C.; Acierno, R. Prevalence Estimates of Combat-Related Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: Critical Review. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2010, 44, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zamorski, M.A.; Bennett, R.E.; Rusu, C.; Weeks, M.; Boulos, D.; Garber, B.G. Prevalence of Past-Year Mental Disorders in the Canadian Armed Forces, 2002–2013. Can. J. Psychiatry 2016, 61 (Suppl. 1), 26S–35S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulton, J.J.; Calhoun, P.S.; Wagner, H.R.; Schry, A.R.; Hair, L.P.; Feeling, N.; Elbogen, E.; Beckham, J.C. The Prevalence of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF) Veterans: A Meta-Analysis. J. Anxiety Disord. 2015, 31, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karstoft, K.-I.; Nielsen, A.B.S.; Andersen, S.B. ISAF7—6,5 År Efter Hjemkomst; Veterancentret: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Reisman, M. PTSD Treatment for Veterans: What’s Working, What’s New, and What’s Next. Pharm. Ther. 2016, 41, 623–627, 632–634. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, B.; Brewin, C.R.; Philpott, R.; Stewart, L. Delayed-Onset Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Am. J. Psychiatry 2007, 164, 1319–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobson, A.; Treloar, S.; Zheng, W.; Anderson, R.; Bredhauer, K.; Kanesarajah, J.; Loos, C.; Pasmore, K. Census Study Report; Centre for Military and Veterans Health, The University of Queensland: Brisbane, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- The Mental Health of the UK Armed Forces. 2013. Available online: https://www.kcl.ac.uk/kcmhr/publications/Reports/Files/mentalhealthsummary.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2018).

- Hoge, C.W.; Terhakopian, A.; Castro, C.A.; Messer, S.C.; Engel, C.C. Association of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder with Somatic Symptoms, Health Care Visits, and Absenteeism among Iraq War Veterans. Am. J. Psychiatry 2007, 164, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lew, H.L.; Otis, J.D.; Tun, C.; Kerns, R.D.; Clark, M.E.; Cifu, D.X.; Otis, J.D.; Tun, C.; Kerns, R.D.; Clark, M.E.; et al. Prevalence of Chronic Pain, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and Persistent Postconcussive Symptoms in OIF/OEF Veterans: Polytrauma Clinical Triad. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2009, 46, 697–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asnaani, A.; Reddy, M.K.; Shea, M.T. The Impact of PTSD Symptoms on Physical and Mental Health Functioning in Returning Veterans. J. Anxiety Disord. 2014, 28, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, S.B.; Haller, M.; Hamblen, J.L.; Southwick, S.M.; Pietrzak, R.H. The Burden of Co-Occurring Alcohol Use Disorder and PTSD in U.S. Military Veterans: Comorbidities, Functioning, and Suicidality. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2018, 32, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keane, T.M.; Kaloupek, D.G. Comorbid Psychiatric Disorders in PTSD. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1997, 821, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milliken, C.S.; Auchterlonie, J.L.; Hoge, C.W. Longitudinal Assessment of Mental Health Problems among Active and Reserve Component Soldiers Returning from the Iraq War. JAMA 2007, 298, 2141–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, D.H.; Doebbeling, C.C.; Schwartz, D.A.; Voelker, M.D.; Falter, K.H.; Woolson, R.F.; Doebbeling, B.N. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Self-Reported Physical Health Status among US Military Personnel Serving during the Gulf War Period: A Population-Based Study. Psychosomatics 2002, 43, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galovski, T.; Lyons, J.A. Psychological Sequelae of Combat Violence: A Review of the Impact of PTSD on the Veteran’s Family and Possible Interventions. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2004, 9, 477–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, D.; Smith, B.N.; Fox, A.B.; Amoroso, T.; Taverna, E.; Schnurr, P.P. Consequences of PTSD for the Work and Family Quality of Life of Female and Male U.S. Afghanistan and Iraq War Veterans. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2017, 52, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, S.L.; Vanstone, M. The Impact of PTSD on Veterans’ Family Relationships: An Interpretative Phenomenological Inquiry. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009, 46, 838–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RAND Corporation. 2008. Available online: http://www.rand.org/news/press/2008/04/17.html (accessed on 1 June 2018).

- Tanielian, T.L.; Jaycox, L. Invisible Wounds of War: Psychological and Cognitive Injuries, Their Consequences, and Services to Assist Recovery; Rand Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2008; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Puetz, T.W.; Youngstedt, S.D.; Herring, M.P. Effects of Pharmacotherapy on Combat-Related PTSD, Anxiety, and Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Regression Analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0126529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipinska, G.; Baldwin, D.S.; Thomas, K.G.F. Pharmacology for Sleep Disturbance in PTSD. Hum. Psychopharmacol. Clin. Exp. 2016, 31, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoge, C.W.; Grossman, S.H.; Auchterlonie, J.L.; Riviere, L.A.; Milliken, C.S.; Wilk, J.E. PTSD Treatment for Soldiers after Combat Deployment: Low Utilization of Mental Health Care and Reasons for Dropout. Psychiatr. Serv. 2014, 65, 997–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Office of Evidence. VA/DOD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Acute Stress Disorder the Management of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Work Group the Office of Quality, Safety and Value; Office of Evidence: Washington, DC, USA, 2017.

- McLay, R.N.; Wood, D.P.; Webb-Murphy, J.A.; Spira, J.L.; Wiederhold, M.D.; Pyne, J.M.; Wiederhold, B.K. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Virtual Reality-Graded Exposure Therapy for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Active Duty Service Members with Combat-Related Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2011, 14, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodson, J.; Helstrom, A.; Halpern, J.M.; Ferenschak, M.P.; Gillihan, S.J.; Powers, M.B. Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in US Combat Veterans: A Meta-Analytic Review 1. Psychol. Rep. 2011, 109, 573–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resick, P.A.; Wachen, J.S.; Mintz, J.; Young-McCaughan, S.; Roache, J.D.; Borah, A.M.; Borah, E.V.; Dondanville, K.A.; Hembree, E.A.; Litz, B.T.; et al. A Randomized Clinical Trial of Group Cognitive Processing Therapy Compared with Group Present-Centered Therapy for PTSD among Active Duty Military Personnel. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 83, 1058–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forbes, D.; Lloyd, D.; Nixon, R.D.V.; Elliott, P.; Varker, T.; Perry, D.; Bryant, R.A.; Creamer, M. A Multisite Randomized Controlled Effectiveness Trial of Cognitive Processing Therapy for Military-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. J. Anxiety Disord. 2012, 26, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frost, N.D.; Laska, K.M.; Wampold, B.E. The Evidence for Present-Centered Therapy as a Treatment for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. J. Trauma. Stress 2014, 27, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorber, H.L. The Use of Horticulture in the Treatment of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in a Private Practice Setting. J. Ther. Hortic. 2011, 21, 18–29. [Google Scholar]

- Steenkamp, M.M.; Litz, B.T.; Hoge, C.W.; Marmar, C.R. Psychotherapy for Military-Related PTSD. JAMA 2015, 314, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haagen, J.F.G.; Smid, G.E.; Knipscheer, J.W.; Kleber, R.J. The Efficacy of Recommended Treatments for Veterans with PTSD: A Metaregression Analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 40, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopwood, T.L.; Schutte, N.S. A Meta-Analytic Investigation of the Impact of Mindfulness-Based Interventions on Post Traumatic Stress. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 57, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polusny, M.A.; Erbes, C.R.; Thuras, P.; Moran, A.; Lamberty, G.J.; Collins, R.C.; Rodman, J.L.; Lim, K.O. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Among Veterans. JAMA 2015, 314, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- O’Malley, P.G. In Veterans with PTSD, Mindfulness-Based Group Therapy Reduced Symptom Severity. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015, 163, 15–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serpa, J.G.; Taylor, S.L.; Tillisch, K. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) Reduces Anxiety, Depression, and Suicidal Ideation in Veterans. Med. Care 2014, 52, S19–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niles, B.L.; Polizzi, C.P.; Voelkel, E.; Weinstein, E.S.; Smidt, K.; Fisher, L.M. Initiation, Dropout, and Outcome from Evidence-Based Psychotherapies in a VA PTSD Outpatient Clinic; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Imel, Z.E.; Laska, K.; Jakupcak, M.; Simpson, T.L. Meta-Analysis of Dropout in Treatments for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 81, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yehuda, R.; Hoge, C.W. The Meaning of Evidence-Based Treatments for Veterans with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 2016, 73, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blais, R.K.; Renshaw, K.D. Stigma and Demographic Correlates of Help-Seeking Intentions in Returning Service Members. J. Trauma. Stress 2013, 26, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, S.M.; Pedersen, E.R.; Marshall, G.N. Combat Experience and Problem Drinking in Veterans: Exploring the Roles of PTSD, Coping Motives, and Perceived Stigma. Addict. Behav. 2017, 66, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonfils, K.A.; Lysaker, P.H.; Yanos, P.T.; Siegel, A.; Leonhardt, B.L.; James, A.V.; Brustuen, B.; Luedtke, B.; Davis, L.W. Self-Stigma in PTSD: Prevalence and Correlates. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 265, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yehuda, R.; Vermetten, E.; McFarlane, A.C.; Lehrner, A. PTSD in the Military: Special Considerations for Understanding Prevalence, Pathophysiology and Treatment Following Deployment. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2014, 5, 25322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahan, E.A.; Estes, D. The Effect of Contact with Natural Environments on Positive and Negative Affect: A Meta-Analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 2015, 10, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Mitchell, R.; de Vries, S.; Frumkin, H. Nature and Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Han, K.-T. The Effect of Nature and Physical Activity on Emotions and Attention While Engaging in Green Exercise. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 24, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidenius, U.; Stigsdotter, U.K.; Dahl Refshauge, A. A Year in the Therapy Forest Garden Nacadia®-Participants’ Use and Preferred Locations in the Garden during a Nature-Based Treatment Program. Int. J. Sustain. Trop. Des. Res. Pract. 2015, 8, 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Corazon, S.S.; Nyed, P.K.; Sidenius, U.; Poulsen, D.V.; Stigsdotter, U.K. A Long-Term Follow-up of the Efficacy of Nature-Based Therapy for Adults Suffering from Stress-Related Illnesses on Levels of Healthcare Consumption and Sick-Leave Absence: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, I.; Choi, H.; Bang, K.-S.; Kim, S.; Song, M.; Lee, B. Effects of Forest Therapy on Depressive Symptoms among Adults: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grahn, P.; Pálsdóttir, A.M.; Ottosson, J.; Jonsdottir, I.H. Longer Nature-Based Rehabilitation May Contribute to a Faster Return to Work in Patients with Reactions to Severe Stress and/or Depression. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Kim, M.S.; Suh, J.K. Effects of Horticultural Therapy of Self-Esteem and Depression of Battered Women at a Shelter in Korea. In Proceedings of the 8th International People-Plant Symposium Proceedings, Awaji, Japan, 4–6 June 2004; pp. 139–142. [Google Scholar]

- Debeer, B.B.; Kimbrel, N.A.; Meyer, E.C.; Gulliver, S.B.; Morissette, S.B. Combined PTSD and Depressive Symptoms Interact with Post-Deployment Social Support to Predict Suicidal Ideation in Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom Veterans. Psychiatry Res. 2014, 216, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimbrel, N.A.; Meyer, E.C.; DeBeer, B.B.; Gulliver, S.B.; Morissette, S.B. A 12-Month Prospective Study of the Effects of PTSD-Depression Comorbidity on Suicidal Behavior in Iraq/Afghanistan-Era Veterans. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 243, 97–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoemaker, C.A. The Profession of Horticultural Therapy Compared with Other Allied Therapies. J. Ther. Hortic. 2002, 13, 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Hewson, M.L. Horticulture as Therapy: A Practical Guide to Using Horticulture as a Therapeutic Tool; Idyll Arbor: Enumclaw, WA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S. The Restorative Benefits of Nature: Toward an Integrative Framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvall, J.; Kaplan, R. Enhancing the Well-Being of Veterans Using Extended Group-Based Nature Recreation Experiences. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2014, 51, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, B.L.; Townsend, J.A.; Garst, B.A. Nature-Based Recreational Therapy for Military Service Members A Strengths Approach. Ther. Recreat. J. 2016, 50, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvall, J.; Kaplan, R. Exploring the Benefits of Outdoor Experiences on Veterans. Ann. Arbor. 2013, 1001, 48109–51041. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S.; Ryan, R. With People in Mind: Design and Management of Everyday Nature; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, N.J.; Norris, J.; D’astous, M. Veterans and the Outward Bound Experience: An Evaluation of Impact and Meaning. Ecopsychology 2014, 6, 165–173. [Google Scholar]

- Poulsen, D.V.; Stigsdotter, U.K.; Refshage, A.D. Whatever Happened to the Soldiers? Nature-Assisted Therapies for Veterans Diagnosed with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Literature Review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corazon, S.S.; Stigsdotter, U.K.; Jensen, A.G.C.; Nilsson, K. Development of the Nature-Based Therapy Concept for Patients with Stress-Related Illness at the Danish Healing Forest Garden Nacadia. J. Ther. Hortic. 2010, 20, 33–51. [Google Scholar]

- Mehling, W.E.; Price, C.; Daubenmier, J.J.; Acree, M.; Bartmess, E.; Stewart, A. The Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness (MAIA). PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hersen, M.; Thomas, J.C. Handbook of Clinical Interviewing with Adults; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, H.J.; Rubin, I. Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data, 3rd ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.; Flowers, P.; Larkin, M. Interpretative Phoneomological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.A. Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, S.J.; Holmes, D. Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) and the Ethics of Body and Place: Critical Methodological Reflections. Hum. Stud. 2014, 37, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanScoy, A.; Evenstad, S.B. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis for LIS Research. J. Doc. 2015, 71, 338–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietkiewicz, I.; Smith, J.A. A Practical Guide to Using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis in Qualitative Research Psychology. Psychol. J. 2014, 20, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Pacella, M.L.; Hruska, B.; Delahanty, D.L. The Physical Health Consequences of PTSD and PTSD Symptoms: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Anxiety Disord. 2013, 27, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gironda, R.J.; Clark, M.E.; Massengale, J.P.; Walker, R.L. Pain among Veterans of Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom. Pain Med. 2006, 7, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bosco, M.A.; Gallinati, J.L.; Clark, M.E. Conceptualizing and Treating Comorbid Chronic Pain and PTSD. Pain Res. Treat. 2013, 2013, 174728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolf, C.J. Central Sensitization: Implications for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pain. Pain 2011, 152, S2–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruden, R.A. Encoding States: A Model for the Origin and Treatment of Complex Psychogenic Pain. Traumatol. Int. J. 2008, 14, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Full Catastrophe Living: How to Cope with Stress, Pain and Illness Using Mindfulness Meditation, 2nd ed.; Bantam Books: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stigsdotter, U.K. Nacadia Healing Forest Garden, Hoersholm Arboretum, Copenhagen, Denmark. In Therapeutic Landscapes: An Evidence-Based Approach to Designing Healing Gardens and Restorative Outdoor Spaces; Marcus, C.C., Sachs, N.A., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 198–205. [Google Scholar]

- Stigsdotter, U.K.; Grahn, P. What Makes a Garden a Healing Garden. J. Ther. Hortic. 2002, 13, 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Coll, J.E.; Weiss, E.L.; Yarvis, J.S. No One Leaves Unchanged: Insights for Civilian Mental Health Care Professionals into the Military Experience and Culture. Soc. Work Health Care 2011, 50, 487–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demers, A. When Veterans Return: The Role of Community in Reintegration. J. Loss Trauma 2011, 16, 160–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, S.B.; Madsen, T.; Karstoft, K.-I.; Elklit, A.; Nordentoft, M.; Bertelsen, M. Efter Afghanistan-Rapport over Soldaters Psykiske Velbefindende to et Halvt År Efter Hjemkomst; Veterancentret: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Green, G.; Emslie, C.; O’Neill, D.; Hunt, K.; Walker, S. Exploring the Ambiguities of Masculinity in Accounts of Emotional Distress in the Military among Young Ex-Servicemen. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 1480–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, L.K. The Importance of Understanding Military Culture. Soc. Work Health Care 2011, 50, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reger, M.A.; Etherage, J.R.; Reger, G.M.; Gahm, G.A. Civilian Psychologists in an Army Culture: The Ethical Challenge of Cultural Competence. Mil. Psychol. 2008, 20, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayers, S.L.; Farrow, V.A.; Ross, J.; Oslin, D.W. Family Problems among Recently Returned Military Veterans Referred for a Mental Health Evaluation. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2009, 70, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottosson, J. The Importance of Nature in Coping with a Crisis: A Photographic Essay. Landsc. Res. 2001, 26, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichberg, H. Body Culture. Phys. Cult. Sport Res. 2009, 46, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, M. Discipline and Punish Trans. The Birth of the Prison; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Poulsen, D.V.; Stigsdotter, U.K.; Davidsen, A.S. “That Guy, Is He Really Sick at All?” An Analysis of How Veterans with PTSD Experience Nature-Based Therapy. Healthcare 2018, 6, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare6020064

Poulsen DV, Stigsdotter UK, Davidsen AS. “That Guy, Is He Really Sick at All?” An Analysis of How Veterans with PTSD Experience Nature-Based Therapy. Healthcare. 2018; 6(2):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare6020064

Chicago/Turabian StylePoulsen, Dorthe Varning, Ulrika K. Stigsdotter, and Annette Sofie Davidsen. 2018. "“That Guy, Is He Really Sick at All?” An Analysis of How Veterans with PTSD Experience Nature-Based Therapy" Healthcare 6, no. 2: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare6020064