Vocational Rehabilitation: Supporting Ill or Disabled Individuals in (to) Work: A UK Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Is Work Important?

3. What Is Rehabilitation?

4. What Is Vocational Rehabilitation (VR)?

- Preparing disadvantaged young people for the world of employment

- Job retention—supporting and maintaining those currently in employment

- Facilitating new work for disadvantaged individuals currently out of employment and unemployed or on ill-health benefits

Brief Historical Perspective

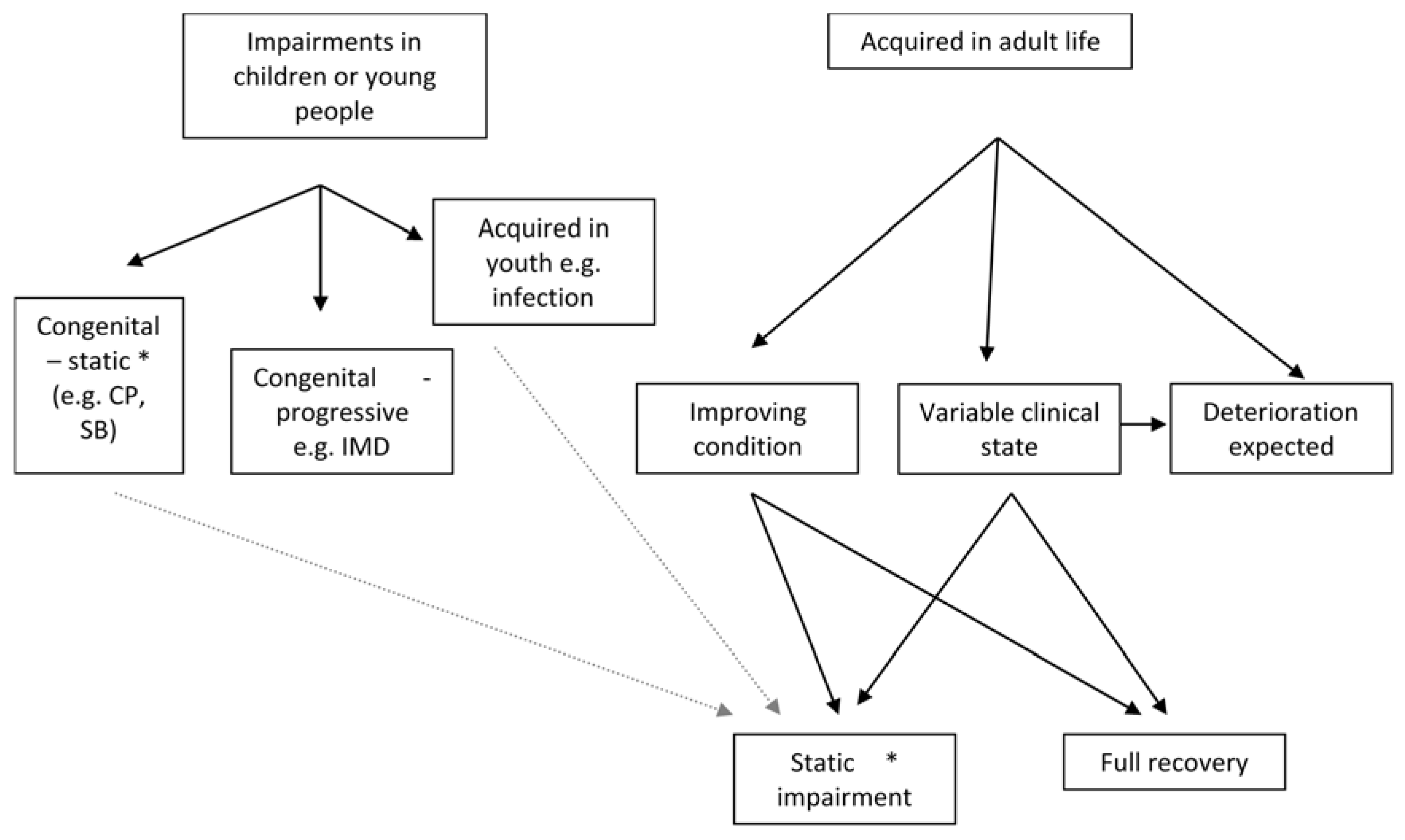

5. Preparing Disadvantaged Young People for the World of Work

Equipment and Assistive Technology

6. Job Retention (JR)—Issues Present Prior to an Episode of Ill Health

6.1. Employers Management Roles

6.2. Occupational Health (OH)

- Minimising the adverse effects of work on health

- Mitigating the effects of ill health on work [64].

6.3. Supervisors and Co-Workers

6.4. Work Instability

7. Job Retention (JR)—Post Prolonged Sickness Absence

Government Roles

8. Finding New Work

9. Some Key Ingredients to Successful VR

9.1. Client Profile

9.2. Facilitating the RTW Process

9.3. Job Modifications (Accommodations)

9.4. Early Intervention

9.5.On-Going Support

9.6. Who Provides the VR?

- Level 1: Information and support provided electronically or through the printed media

- Level2: One-to-one support through telephone hotlines and digital media

- Level 3: Self-management programmes access during or after treatment

- Level 4: Specialist VR services [126].

9.7. Charitable or Voluntary Sector

9.7.1. “Top-Down” Services

9.7.2. “Bottom-Up” Services

10. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bevan, S. Exploring the benefits of early interventions which help people with chronic illness remain in work. Available online: http://www.fitforworkeurope.eu/Downloads/Economics%20of%20Early%20Intervention%20FINAL.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2016).

- Kenyon, P. Cost Benefit Analysis of Rehabilitation Services Provided by Crs Australia; Curtin University of Technology: Perth, Australia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Waddell, G.; Burton, A.K.; Kendall, N. Vocational Rehabilitation: What works, for Whom, and When? The Stationary Office: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ruskin, J. Sesame and Lilies. Lecture I.—Sesame: Of Kings’ Treasuries. Essays: English and American; The Harvard Classics: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1909. [Google Scholar]

- Waddell, G.; Burton, A.K. Is Work Good for Your Health and Well-Being? The Stationary Office: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Black, D.C. Working for A Healthier Tomorrow; The Stationary Office: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Black, D.C.; Frost, D. Health at Work: An Independent Review of Sickness Absence; The Stationary Office: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Work and Pensions. Fitness to Work: The Government’s Response to ‘Health at Work—An Independent Review of Sickness Absence’; Department for Work and Pensions: London, UK, 2013.

- World Health Organization. Report by the Secretariat. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICIDH-2); World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sayce, L. Aspirations of people with ill health, injury, disability. In Proceedings of the BSI/UKRC Conference, London, UK, 5 April 2011.

- British Society of Rehabilitation Medicine. Vocational Assessment and Rehabilitation for People with Long-Term Neurological Conditions: Recommendations for Best Practice, 1st ed.; British Society of Rehabilitation Medicine: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vocational Rehabilitation Association. Vocational Rehabilitation Standards of Practice, 2nd ed.; Vocational Rehabilitation Association: Doncaster, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- British Society of Rehabilitation Medicine. Vocational Rehabilitation—The Way Forward: Report of A Working Party (Chair Frank, A.O.), 1st ed.; British Society of Rehabilitation Medicine: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Corden, A.; Thornton, P. Employment Programmes for Disabled People: Lessons from Research Evaluations; HMSO: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain, M.A.; Ekholm, J.; Gutenbrunner, C.; Schuldt, K.; Ekholm, J.; Wedsterhall, L.V.; Frank, A.O.; Juocevicius, A.; Glaesener, J-J. European perspectives on rehabilitation medicine and vocational rehabilitation. J. Rehabil. Med. 2010, 42, 385–392. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, A.O.; Thurgood, J. Vocational rehabilitation in the UK: Opportunities for health-care professionals. Int. J. Ther. Rehabil. 2006, 13, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastasia, I.; Coutu, M.F.; Tcaciuc, R. Topics and trends in research on non-clinical interventions aimed at preventing prolonged work disability in workers compensated for work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WRMSDs): A systematic, comprehensive literature review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2014, 36, 1841–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beveridge, W.H. Social Insurance and Allied Services. Report by Sir William Beveridge Presented to Parliament by Command of His Majesty, November 1942; HMSO: London, UK, 1942. [Google Scholar]

- British Society of Rehabilitation Medicine. Vocational Rehabilitation—The Way Forward: Report of A Working Party (Chair: Frank, A.O.), 2nd ed.; British Society of Rehabilitation Medicine: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, A.O.; Chamberlain, M.A. Rehabilitation: An integral part of modern medical practice. Occup. Med. 2006, 56, 289–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aylward, M.; Sawney, P. Support and rehabilitation (restoring fitness for work). In Fitness for Work: The Medical Aspects, 4th ed.; Palmer, K.T., Cox, R., Brown, I., Eds.; Faculty of Occupational Medicine of the Royal College of Physicians: London, UK, 2007; pp. 69–89. [Google Scholar]

- Waddell, G.; Aylward, M.; Sawney, P. Back pain, Incapacity for Work and Social Security Benefits: An International Literature Review and Analysis; Royal Society of Medicine Press Ltd.: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, A.O.; Sawney, P. Vocational rehabilitation. J. R. Soc. Med. 2003, 96, 522–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattingly, S. Rehabilitation Today in Great Britain, 2nd ed.; Update Books Ltd.: London, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Grahame, R. The decline of rehabilitation services and its impact on disability benefits. J. R. Soc. Med. 2002, 95, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CMSUK. CaseManagement Society of the UK; CMSUK: Sutton, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Weston, M.; Winpenny, E.; Manning, J. Working Together: Promoting Work as a Health Outcome as the NHS Reforms; 2020 health.org: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, J. Planning the Future: Implications for Occupational Health; Delivery and Training—Executive Summary; Council for Work & Health: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, M.; Lock, A.; Scott, R. No Voice, No Choice: Disabled People’s Experiences of Accessing Communication Aids; Scope: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Madej-Pilarczyk, A. Professional activity of Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy patients in Poland. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health. 2014, 27, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, S.; Neophytou, C.; De Souza, L.H.; Frank, A.O. Young people’s experiences using electric powered indoor-outdoor wheelchairs (EPIOCs): Potential for enhancing users’ development? Disabil. Rehabil. 2007, 19, 1281–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayce, L. Young people with chronic conditions and the transition from education to employment. In Proceedings of the Work Foundation Seminar, London, UK, 23 February 2016.

- Matthews, L. Unlimited Potential: A Research Report into Hearing Loss in the Workplace, 1st ed.; Action on Hearing Loss: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Disability Rights UK. Into Further Education 2015: For Anyone with Learning, Health or Disability Issues; Disability Rights UK: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, P.; Stevens, T. Get Back to Where We Do Belong; Disability Rights UK: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, D. Getting A Job: Advice for Family Carers of Adults with A Learning Disability; Mental Health Foundation: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, A.; Douglas, G.; Lynch, P. Tackling Unemployment for Blind and Partially Sighted People: Summary of Findings from AThree-YearResearch Project (ENABLER); RNIB, University of Birmingham: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hoving, J.L.; van Zwieten, M.C.; van der Meer, M.; Sluiter, J.K.; Frings-Dresen, M.H. Work participation and arthritis: A systematic overview of challenges, adaptations and opportunities for interventions. Rheumatology 2013, 52, 1254–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodger, S.; Woods, K.L.; Bladen, C.L.; Stringer, A.; Vry, J.; Gramsch, K.; Kirschner, J.; Thompson, R.; Bushby, K.; Lochmuller, H. Care provision for adults with Duchenne muscular dystrophy in the UK: Compliance with international consensus care guidelines. Neuromusc. Disord. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, S.; Sloper, P.; Moran, N.; Cusworth, L.; Beecham, J. Multi-agency transition services; greater collaboration needed to meet the priorities of young disabled people with complex needs as they move into adulthood. J. Integrated Care 2011, 19, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roebroeck, M.E.; Jahnsen, R.; Carona, C.; Kent, R.M.; Chamberlain, M.A. Adult outcomes and lifespan issues for people with childhood-onset physical disability. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2009, 51, 670–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, S.N.; Frank, A.O.; Hanspal, R.S.; Groves, R. Exploring environmental control unit use in the age group 10–20 years. Int. J. Ther. Rehabil. 2006, 13, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, A.O. Transition: Provision of assistive technology can enhance independence and reduce carer strain. Avaliable online: http://www.clinmed.rcpjournal.org/content/7/2/198.1.full.pdf+html (accessed on 1 July 2016).

- McNaughton, D.; Symons, G.; Light, J.; Parsons, A. ‘My dream was to pay taxes’: The self-employment experiences of individuals who use augmentative and alternative communication. J. Vocat. Rehabil. 2006, 25, 181–196. [Google Scholar]

- Communication Matters. Funding for Communication Aids; Communication Matters: Edinburgh, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, A.O.; Ward, J.H.; Orwell, N.J.; McCullagh, C.; Belcher, M. Introduction of the new NHS Electric Powered Indoor/outdoor Chair (EPIOC) service: benefits, risks and implications for prescribers. Clin. Rehabil. 2000, 14, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, S.; Frank, A.; Neophytou, C.; De Souza, L.H. Older adults’ use of, and satisfaction with, electric powered indoor/outdoor wheelchairs. Age Ageing 2007, 36, 431–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, A.O.; Neophytou, C.; Frank, J.; De Souza, L.H. Electric Powered Indoor/outdoor Wheelchairs (EPIOCs): Users views of influence on family, friends and carers. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2010, 5, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, A.O.; Ellis, K.; Yates, M. Use of the voucher scheme for provision of Electric Powered Indoor/outdoor Wheelchairs (EPIOCs). Posture Mobil. 2008, 23, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, A.O. Motor neurone disease: Practical update ignores rehabilitative approaches—Particularly assistive technology. Clin. Med. 2010, 10, 640–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health & Safety Executive. Managing Sickness Absence and Return to Work: An Employers’ and Managers Guide; HSE Books: Norwich, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bertilsson, M.; Petersson, E.L.; Ostlund, G.; Waern, M.; Hensing, G. Capacity to work while depressed and anxious—A phenomenological study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2013, 35, 1705–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dionne, C.E.; Bourbonnais, R.; Frémont, P.; Rossignol, M.; Stock, S.R.; Laperrière, E. Obstacles to and facilitators of return to work after work-disabling back pain: the workers’ perspective. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2013, 23, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flach, P.A.; Groothoff, J.W.; Bultmann, U. Identifying employees at risk for job loss during sick leave. Disabil. Rehabil. 2013, 35, 1835–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNamee, S.; Walker, W.; Cifu, D.X.; Wehman, P.H. Minimizing the effect of TBI-related physical sequelae on vocational return. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2009, 46, 893–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntsiea, M.V. The Effect of a Workplace Intervention Programme on Return to Work after Stroke. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Palstam, A.; Gard, G.; Mannerkorpi, K. Factors promoting sustainable work in women with fibromyalgia. Disabil. Rehabil. 2013, 35, 1622–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radford, K.; Phillips, J.; Drummond, A.; Sach, T.; Walker, M.; Tyerman, A.; Haboubi, N.; Jones, T. Return to work after traumatic brain injury: Cohort comparison and economic evaluation. Brain Inj. 2013, 27, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Squires, H.; Rick, J.; Carroll, C.; Hillage, J. Cost-effectiveness of interventions to return employees to work following long-term sickness absence due to musculoskeletal disorders. J. Public Health 2012, 34, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyerman, A. Vocational rehabilitation after traumatic brain injury: Models and services. NeuroRehabilitation 2012, 31, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wainwright, E.; Wainwright, D.; Keogh, E.; Eccleston, C. Return to work with chronic pain: Employers’ and employees’ views. Occup. Med. 2013, 63, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westmorland, M.; Williams, R.; Amick, B.; Shannon, H.; Rasheed, F. Disability management practices in Ontario workplaces: Employees’ perceptions. Disabil. Rehabil. 2005, 27, 825–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Occupational Health Advisory Committee. Occupational Health Advisory Committee Report and Recommendations on Improving Access to Occupational Health Support; Health and Safety Executive: London, UK, 2000.

- Ford, J.; Parker, G.; Ford, F.; Kloss, D.; Pickvance, S.; Sawney, P. Rehabilitation for Work Matters; Radcliffe Publishing Ltd.: Abingdon, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, L.M.; Curran, A.D.; Eskin, F.; Fishwick, D. Provision and perception of occupational health in small and medium-sized enterprises in Sheffield, UK. Occup. Med. 2001, 51, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, K.; Kendall, N. Musculoskeletal disorders. BMJ 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekberg, K. Workplace changes in successful rehabilitation. J. Occup. Rehabil. 1995, 5, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marhold, C.; Linton, S.J.; Melin, L. Identification of obstacles for chronic pain patients to return to work: Evaluation of a questionnaire. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2002, 12, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, I.Z.; Crook, C.; Meloche, G.R.; Berkowitz, J.; Milner, R.; Zuberbier, O.A.; Meloche, W. Psychosocial factors predictive of occupational low back disability: Towards development of a return-to-work model. Pain 2004, 107, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, D.; Kirkpatrick, P.; McCulloch, S. Sustaining adults with dementia or mild cognitive impairment in employment: A systematic review protocol of qualitative evidence. JBI Database System. Rev. Implement. Rep. 2015, 13, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnussen, L.; Strand, L.I.; Skouen, J.; Eriksen, H. Motivating disability pensioners with back pain to return to work—A randomized controlled trial. J. Rehabil. Med. 2007, 39, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swift, M.B.; Cole, D.C.; Beaton, D.E.; Manno, M. Health care utilization and workplace interventions for neck and upper limb problems among newspaper workers. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2001, 43, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Post, M.; Krol, B.; Groothoff, J.W. Work-related determinants of return to work of employees on long-term sickness absence. Disabil. Rehabil. 2005, 27, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandola, T.; Brunner, E.; Marmot, M. Chronic stress at work and the metabolic syndrome: Prospective study. BMJ 2006, 332, 521–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, T.W.; Lau, K.T.; Ho, C.W.; Ma, M.C.; Yeung, T.F.; Cheung, P.M. A study on the prevalence of and risk factors for neck pain in secondary school teachers. Public Health 2006, 120, 563–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henriksson, C.M.; Liedberg, G.M.; Gerdle, B. Women with fibromyalgia: Work and rehabilitation. Disabil. Rehabil. 2005, 27, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanahan, E.M.; Ahern, M. Inflammatory arthritis and work disability: What is the role of occupational medicine? Occup. Med. 2008, 58, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torp, S.; Riise, T.; Moen, B.E. The impact of social and organizational factors on workers’ coping with musculoskeletal symptoms. Physical Ther. 2001, 81, 1328–1338. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, T.; Lam, P. The prevalence of and risk factors for neck pain and upper limb pain among secondary school teachers in Hong Kong. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2007, 17, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheldof, E.; Vinck, J.; Vlaeyen, J.; Hidding, A.; Crombez, G. Development of and recovery from short- and long-term low back pain in occupational settings: a prospective cohort study. Eur. J. Pain. 2007, 11, 841–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trajectory. Mental Health: Still the Last Workplace Taboo? Shaw Trust: Egham, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schelly, C.; Sample, P.; Spencer, K. The Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990 expands employment opportunities for persons with developmental disabilities. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 1992, 46, 457–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchinson, N.L.; Versnel, J.; Chin, P.; Munby, H. Negotiating accommodations so that work-based education facilitates career development for youth with disabilities. Work 2008, 30, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wehman, P.H.; Revell, W.G.; Kregel, J.; Kreutzer, J.S.; Callahan, M.; Banks, P.D. Supported employment: An alternative model for vocational rehabilitation of persons with severe neurologic, psychiatric, or physical disability. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1991, 72, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gilworth, G.G.; Chamberlain, M.A.; Harvey, A.; Woodhouse, A.; Smith, J.; Smyth, M.G.; Tennant, A. Development of a work instability scale for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthr. Rheum. 2003, 49, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilworth, G.; Emery, P.; Barkham, N.; Smyth, M.G.; Helliwell, P.; Tennant, A. Reducing work disability in Ankylosing Spondylitis: Development of a work instability scale for AS. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilworth, G.; Smyth, G.; Smith, J.; Tennant, A. The development and validation of the Office Work Screen. Occup. Med. 2008, 58, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilworth, G.; Bhakta, B.; Eyres, S.; Carey, A.; Chamberlain, M.A.; Tennant, A. Keeping nurses working: development and psychometric testing of the Nurse-Work Instability Scale (Nurse-WIS). J. Adv. Nurs. 2007, 57, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilworth, G.G.; Haigh, R.; Tennant, A.; Chamberlain, M.A.; Harvey, A.R. Do rheumatologists recognise their patients work-related problems? Rheumatology 2001, 40, 1206–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical Standards Advisory Group—Chairman Prof Rosen,M. Back Pain; HMSO: London, UK, 1994.

- Wade, D. Complexity, case-mix and rehabilitation: The importance of a holistic model of illness. Clin. Rehabil. 2011, 25, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendall, N.; Burton, A.K. Tackling Musculoskeletal Problems: A Guide for Clinic and Workplace—Identifying Obstacles Using the Psychosocial Flags Framework; TSO: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen, S.J.; Anema, J.R.; Schellart, A.J.; van Mechelen, W.; van der Beek, A.J. Cost-effectiveness of a participatory return-to-work intervention for temporary agency workers and unemployed workers sick-listed due to musculoskeletal disorders: Design of a randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Government Equalities Office. Equality Act 2010. Available online: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/contents (accessed on 3 March 2016).

- Bardgett, M.; Lally, J.; Malviya, A.; Kleim, B.; Deehan, D. Patient-reported factors influencing return to work after joint replacement. Occup. Med. 2016, 66, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiabane, E.; Argentero, P.; Calsamiglia, G.; Candura, S.M.; Giorgi, I.; Scafa, F.; Rugulies, R. Does job satisfaction predict early return to work after coronary angioplasty or cardiac surgery? Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2013, 86, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department for Work & Pensions. Access to Work; Department for Work and Pensions: London, UK, 2012.

- Tyerman, A.; Meehan, M. Vocational Assessment and Rehabilitation after Acquired Brain Injury: Inter-Agency Guidelines; BSRM, Jobcentre Plus, Royal College of Physicians: London, UK, 2004.

- Sweetland, J.; Howse, E.; Playford, E.D. A systematic review of research undertaken in vocational rehabilitation for people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil. Rehabil. 2012, 34, 2031–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Prinz, C. Mental Health and Work: United Kingdom, Mental Health and Work; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Work and Pensions. Fit for Work: Guidance for Employers; DWP: London, UK, 2014.

- Department for Work and Pensions. Fit for Work: Guidance for Employers; DWP: London, UK, 2015.

- Hanson, M.; Wu, O.; Smith, J. Working Health Services: Evaluation of the Projects Delivered in the Borders, Dundee and Lothian; HealthyWorking Lives, NHS Scotland: Edinburgh, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Psychiatrists (CR111). Employment Opportunities and Psychiatric Disability. A Report of the Royal College of Psychiatrists (Chair Boardman, J.); Royal College of Psychiatrists: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wales Council for Voluntary Action. The Intermediate Labour Market (ILM); WCVA North Wales Office: Denbighshire, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Frostad Liaset, I.; Lorås, H. Perceived factors in return to work after acquired brain injury: A qualitative meta-synthesis. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozzer, M.; Samsom, D.; Anson, J. An evaluation of a community-based vocational rehabilitation program for adults with psychiatric disabilities. Can. J. Community Mental Health 1999, 18, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinokur, A.D.; Schul, Y. Mastery and inoculation against setbacks as active ingredients in the JOBS intervention for the unemployed. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 1997, 65, 867–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hees, H.L.; Koeter, M.W.; Schene, A.H. Predictors of long-term return to work and symptom remission in sick-listed patients with major depression. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2012, 73, e1048–e1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stergiou-Kita, M.; Grigorovich, A.; Tseung, V.; Milosevic, E.; Hebert, D.; Phan, S.; Jones, J. Qualitative meta-synthesis of survivors’ work experiences and the development of strategies to facilitate return to work. J Cancer Surviv. 2014, 8, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiedtke, C.; Dierckx de Casterlé, B.; Donceel, P.; de Rijk, A. Workplace support after breast cancer treatment: Recognition of vulnerability. Disabil. Rehabil. 2015, 37, 1770–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergvik, S.; Sørlie, T.; Wynn, R. Coronary patients who returned to work had stronger internal locus of control beliefs than those who did not return to work. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 596–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, X.; Collado, A.; Arias, A.; Peri, J.M.; Bailles, E.; Salamero, M.; Valdés, M. Pain locus of control predicts return to work among Spanish fibromyalgia patients after completion of a multidisciplinary pain program. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2009, 31, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiegmann, S.M.; Berven, N.L. Health locus-of-control beliefs and improvement in physical functioning in a work-hardening, return-to-work program. Rehabil. Psychol. 1998, 43, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Work and Pensions. Building Capacity for Work: A UK Framework for Vocational Rehabilitation; DWP: London, UK, 2004.

- Lovvik, C.; Overland, S.; Hysing, M.; Broadbent, E.; Reme, S.E. Association between illness perceptions and return-to-work expectations in workers with common mental health symptoms. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2014, 24, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busch, M.A. Sociodemographic differences in return to work after stroke: The South London Stroke Register (SLSR). J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 2009, 80, 888–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, A.O. Management of chronic pain in older adults: Symptoms of post-traumatic psychological distress should be sought. BMJ 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, A.O. Understanding back injuries and back pain. In Medical Aspects of Personal Injury Litigation; Barnes, M.P., Braithwaite, B., Ward, A., Eds.; Blackwell Science: Oxford, UK, 1997; pp. 164–209. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, J.; Frank, A. Post-traumatic psychological distress may present in rheumatology clinics. BMJ 2002, 325, 221, PMC1123732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vauth, R.; Corrigan, P.W.; Clauss, M.; Dietl, M.; Dreher-Rudolph, M.; Stieglitz, R.D.; Vater, R. Cognitive strategies versus self-management skills as adjunct to vocational rehabilitation. Schizophr. Bull. 2005, 31, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamer, H.; Gandhi, R.; Wong, S.; Mahomed, N.N. Predicting return to work following treatment of chronic pain disorder. Occup. Med. 2013, 63, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, A.O.; De Souza, L.H.; Frank, C.A. Neck pain and disability: A cross-sectional survey of the demographic and clinical characteristics of neck pain seen in a rheumatology clinic. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2005, 59, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micklewright, J.L.; Yutsis, M.; Smigielski, J.S.; Brown, A.W.; Bergquist, T.F. Point of entry and functional outcomes after comprehensive day treatment participation. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2011, 92, 1974–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.; Mackay, D.; Demou, E.; Craig, J.; Macdonald, E. Reducing Sickness Absence in Scotland—Applying the Lessons from A Pilot NHS Intervention; University of Glasgow: Glasgow, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gail, E. ThinkingPositively about Work: Delivering Work Support and Vocational Rehabilitation for People with Cancer; Macmillan Cancer Support, Department of Health, University College London: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Playford, E.D.; Radford, K.; Burton, C.; Gibson, A.; Jellie, B.; Watkins, C. Mapping Vocational Rehabilitation Services for People with Long-Term Neurological Conditions. Available online: https://www.networks.nhs.uk/nhs-networks/vocational-rehabilitation/documents/FinalReport.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2016).

- Burns, T.; Catty, J.; Becker, T.; Drake, R.E.; Fioritti, A.; Knapp, M.; Lauber, C.; Rössler, W.; Tomov, T.; van Busschbach, J.; et al. The effectiveness of supported employment for people with severe mental illness: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007, 370, 1146–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kullman, J.A. Patient advocacy organizations: Key partners in research on rare diseases. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2010, 3, S7. [Google Scholar]

- McEnhill, L.; Steadman, K.; Bajorek, Z. Peer Support for Employment: A Review of the Evidence; The Work Foundation: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sayce, L.; Fagelman, N. Peer Support for Employment: A Practice Review; Disability Rights UK: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan Cancer Support. Work and Cancer; MacMillan Cancer Support: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley, S.E.; Goodwin, P.C.; Goldbart, J. Experiences of attendance at a neuromuscular centre: Perceptions of adults with neuromuscular disorders. Disabil. Rehabil. 2011, 33, 1022–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enham Trust Disability Charity. Available online: https://www.enhamtrust.org.uk/?gclid=CK2Gv5ub-swCFUHGGwodmmcLnw (accessed on 27 May 2016).

- Whizz-Kidz. Available online: http://www.whizz-kidz.org.uk/ (accessed on 27 May 2016).

|

| From: Vocational Rehabilitation Association letter to Lord Freud March 2011 |

| Red— | severity of impairment (a) |

| Yellow— | psychosocial obstacles (b) |

| Orange— | those with pre-existing psychological impairments (b) |

| Blue— | perceived obstacles in the workplace—changeable (c) |

| Black— | unalterable obstacles—e.g., national agreements (c) |

| Chequered— | social obstacles (c) [64] |

| a | Biological |

| b | Psychological |

| c | Social |

| a–c | Reflect components of the “bio-psycho-social” model |

| Flexibility in hours and/or duties, e.g.,: |

|

| Adaptations, equipment and coping strategies, e.g., |

|

| Additional training, supervision and support, e.g.,: |

|

|

|

© 2016 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Frank, A. Vocational Rehabilitation: Supporting Ill or Disabled Individuals in (to) Work: A UK Perspective. Healthcare 2016, 4, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare4030046

Frank A. Vocational Rehabilitation: Supporting Ill or Disabled Individuals in (to) Work: A UK Perspective. Healthcare. 2016; 4(3):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare4030046

Chicago/Turabian StyleFrank, Andrew. 2016. "Vocational Rehabilitation: Supporting Ill or Disabled Individuals in (to) Work: A UK Perspective" Healthcare 4, no. 3: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare4030046