The Use of Best Practice in the Treatment of a Complex Diabetic Foot Ulcer: A Case Report

Abstract

:1. Introduction

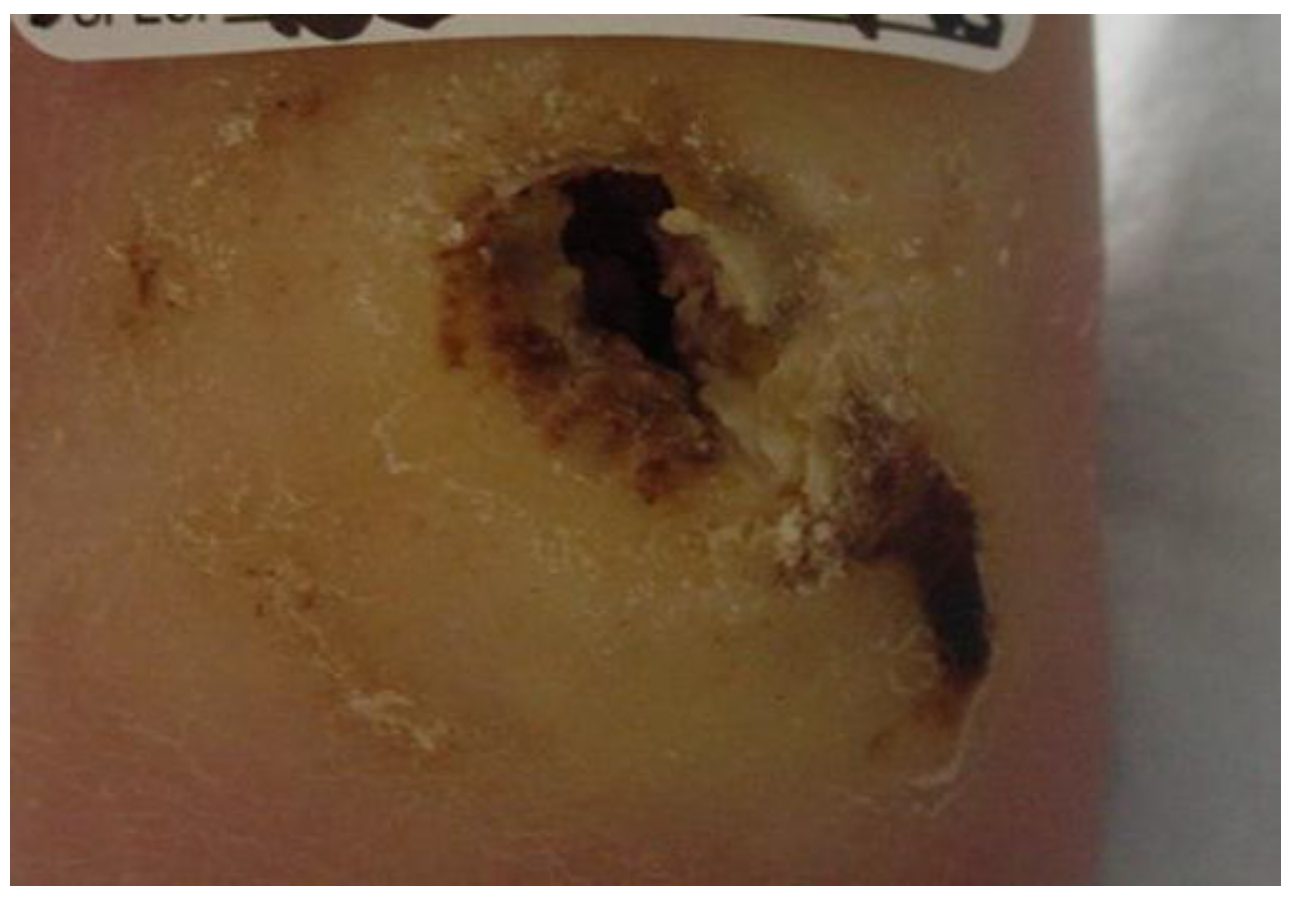

2. Case Description

3. Examination

4. Tests and Measures

5. Evaluation

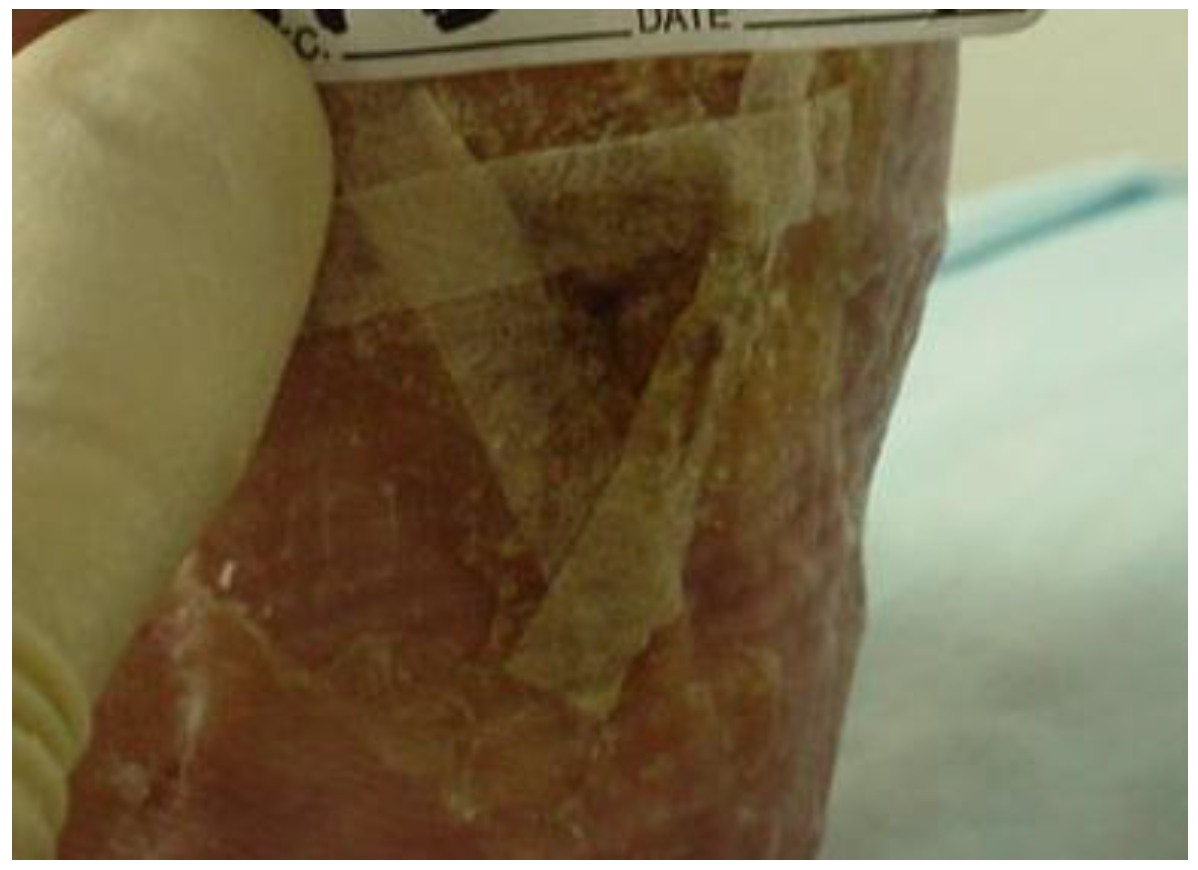

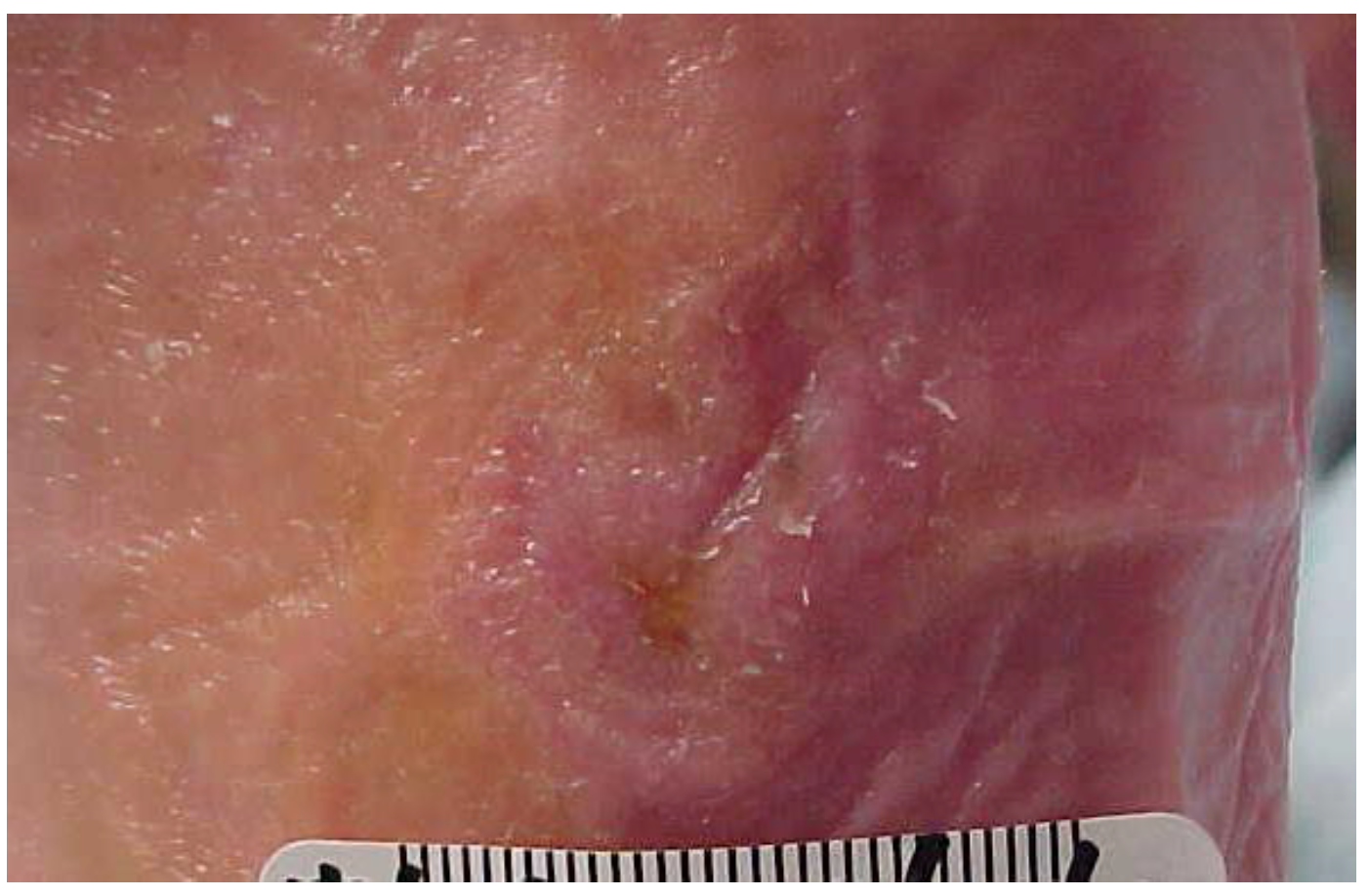

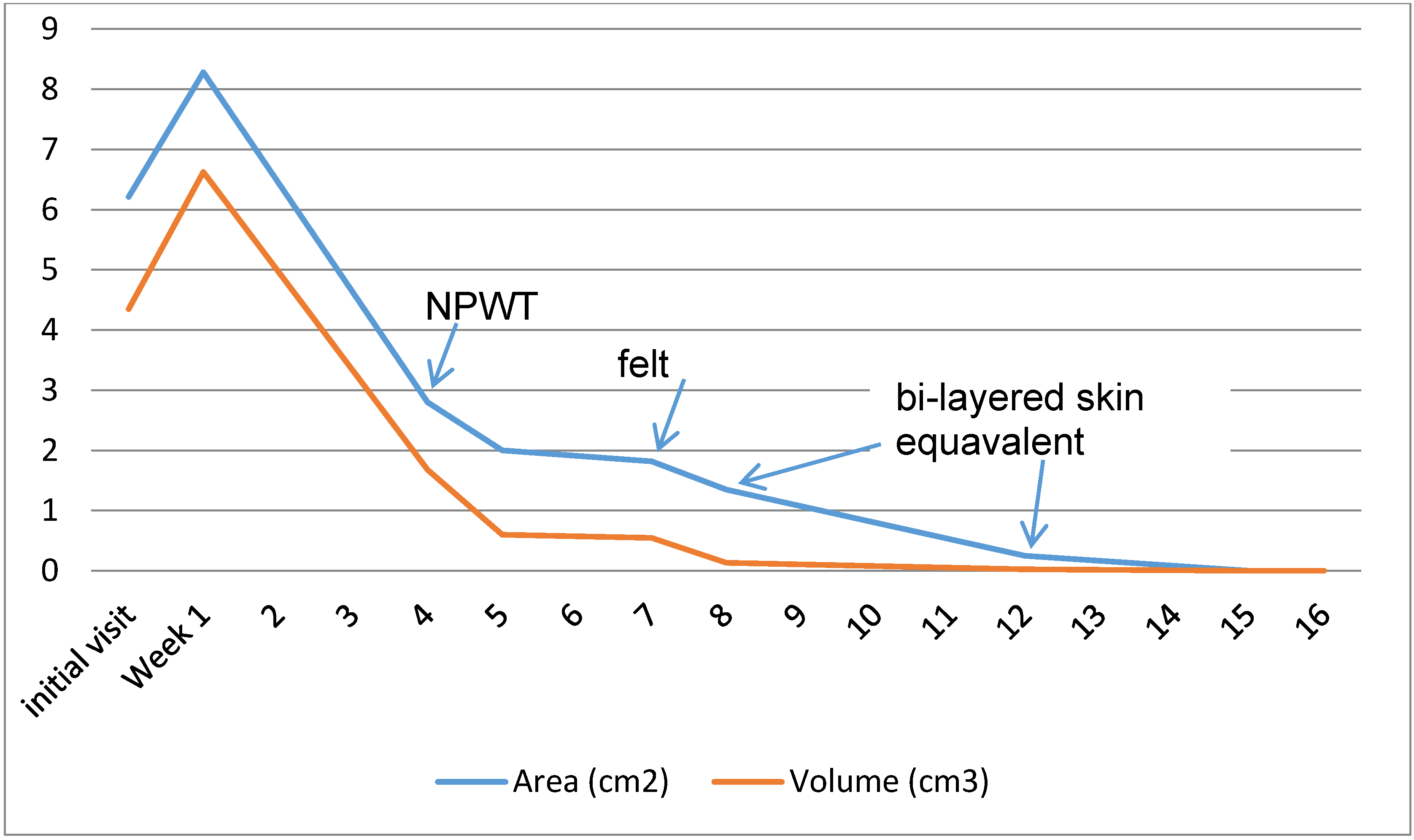

6. Intervention

7. Outcomes

8. Discussion

9. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report: Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2014.

- Boulton, A.J.M.; Malik, R.A.; Arezzo, J.C.; Sosenko, J.M. Diabetic somatic neuropathies: Technical review. Diabetes Care 2004, 27, 1458–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiber, G.E.; Vileikyte, L.; Boyko, E.J.; Aguila, M.; Smith, D.G.; Lavery, L.A.; Boulton, A.J. Causal pathways for incident lower-extremity ulcers in patients with diabetes from two settings. Diabetes Care 1999, 22, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulton, A.J.M.; Armstrong, D.G.; Albert, S.F.; Frykberg, R.G.; Hellman, R.; Kirkman, M.S.; Lavery, L.A.; Lemaster, J.W.; Mills, J.L., Sr.; Mueller, M.J.; et al. Comprehensive foot examination and risk assessment: A report of the task force of the foot care interest group of the American Diabetes Association, with endorsement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 1679–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregg, E.W.; Sorlie, P.; Paulose-Ram, R.; Gu, Q.; Eberhardt, M.S.; Wolz, M.; Burt, V.; Curtin, L.; Engelgau, M.; Geiss, L. Prevalence of lower-extremity disease in the US adult population ≥40 years of age with and without diabetes: 1999–2000 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Diabetes Care 2004, 27, 1591–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Armstrong, D.G.; Lipsky, B.A. Preventing foot ulcers in patients with diabetes. JAMA 2005, 293, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pecoraro, R.E.; Reiber, G.E.; Burgess, E.M. Pathways to diabetic limb amputation: Basis for prevention. Diabetes Care 1990, 13, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frykberg, R.G. Diabetic foot ulcers: Pathogenesis and management. Am. Fam. Physician 2002, 66, 1655–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margolis, D.; Malay, D.S.; Hoffstad, O.J.; Leonard, C.E.; MaCurdy, T.; de Nava, K.L.; Tan, Y.; Molina, T.; Siegel, K.L. Incidence of Diabetic Foot Ulcer and Lower Extremity Amputation among Medicare Beneficiaries, 2006 to 2008; University of Pennsylvania DEcIDE Center: Rockville, MD, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Young, M.J.; McCardle, J.E.; Randall, L.E.; Barclay, J.I. Improved survival of diabetic foot ulcer patients 1995–2008: Possible impact of aggressive cardiovascular risk management. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 2143–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, D.G.; Wrobel, J.; Robbins, J.M. Guest editorial: Are diabetes related wounds and amputations worse than cancer? Int. Wound J. 2007, 4, 286–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavery, L.A.; Armstrong, D.A.; Wunderlich, R.P.; Mohler, M.J.; Wendel, C.S.; Lipsky, B.A. Risk factors for foot infections in individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 1288–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.; Weinberger, M.; Katz, B.P. A controlled trial to increase office visits and reduce hospitalization in diabetic patients. J. Gen. Int. Med. 1987, 2, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Best Practice Guidelines: Wound Management in Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Wounds International 2013. Available online: http://www.woundsinternational.com/media/issues/673/files/content_10803.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2015).

- Brem, H.; Sheehan, P.; Boulton, A.J. Protocol for Treatment of Diabetic foot Ulcers. Am. J. Surg. 2004, 187, 1S–10S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.C.; Driver, V.R.; Wrobel, J.S.; Armstrong, D.G. Foot Ulcers in the Diabetic Patient, Prevention and Treatment. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2007, 3, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jeffcoate, W.J.; Harding, K.G. Diabetic foot ulcers. Lancet 2003, 361, 1545–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot. Summary Guidance for the Daily Practice. 2015. Available online: http://www.iwgdf.org/files/2015/website_summary.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2015).

- Boyko, E.J.; Ahroni, J.H.; Cohen, V.; Nelson, K.M.; Heagerty, P.J. Prediction of diabetic foot ulcer occurrence using commonly available clinical information: The Seattle Diabetic Foot Study. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 1202–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, D.G.; Lavery, L.A.; Vela, S.A.; Quebedeaux, T.L.; Fleischli, J.G. Choosing a practical screening instrument to identify patients at risk for diabetic foot ulceration. Arch. Intern Med. 1998, 158, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vowden, K.R.; Goulding, V.; Vowden, P. Hand held Doppler assessment for Peripheral arterial disease. J. Wound Care 1996, 5, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Young, M.; Birch, I.; Potter, C.A.; Saunders, R.; Otter, S.; Hussain, S.; Pellett, J.; Reynolds, N.; Jenkin, S.; Wright, W. A comparison of the Doppler ultrasound interpretation by student and registered podiatrists. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2013, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Qaisi, M.; Nott, D.M.; King, D.H.; Kaddoura, S. Ankle Brachial Pressure Index (ABPI): An update for practitioners. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2009, 5, 833–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Sullivan, S.B.; Schmitz, T.J. Physical Rehabilitation: Assessment and Treatment, 5th ed.; F.A. Davis Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2007; p. 659. [Google Scholar]

- Bates-Jensen, B.; Vredevoe, D.; Brecht, M. Validity and reliability of the pressure sore status tool. Decubitus 1992, 5, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sussman, C.; Bates-Jensen, B. Wound Care: A Collaborative Practice Manual for Health Professionals, 3rd ed.; Wolters Kluwar: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, F.W. The dysvascular foot: A system of diagnosis and treatment. Foot Ankle 1981, 2, 64–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Physical Therapy Association. Guide to Physical Therapist Practice, 2nd ed.; American Physical Therapy Association: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- National Diabetes Education Program. Four Steps to Manage Your Diabetes for Life; The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- European Wound Management Association (EWMA). Position Document: Wound Bed Preparation in Practice; MEP Ltd.: London, UK, 2004; Available online: http://woundsinternational.com (accessed on July 2015).

- Steed, D.L.; Donohoe, D.; Webster, M.W.; Lindsley, L. Effect of extensive debridement and treatment on healing of diabetic foot ulcers. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 1996, 183, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Koeveker, G.B. Surgical Debridement of Wounds. In Cutaneous Wound Healing; Falanga, V., Ed.; Martin Dunitz: London, UK, 2001; pp. 233–245. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulrazak, A.; Bitar, Z.I.; Al-Shamali, A.A.; Mobasher, L.A. Bacteriological study of diabetic foot infections. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2005, 19, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, T.K.; Leigh, R.D.; Tsui, J. Diabetic foot disease and oedema. Br. J. Diabetes Vasc. Disease 2013, 13, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowering, C.K. Use of layered compression bandages in diabetic patients. Experience in patients with lower leg ulceration, peripheral edema, and features of venous and arterial disease. Adv. Wound Care 1998, 11, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thomas, S. Compression Bandaging in the Treatment of Venous Leg Ulcers. Available online: http://www.worldwidewounds.com/1997/september/Thomas-Bandaging/bandage-paper.html (accessed on 20 July 2015).

- American Diabetes Association. Consensus Development Conference on Diabetic Foot Wound Care, Boston, Massachusetts. American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 1999, 22, 1354–1360. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.C.; Crews, R.T.; Armstrong, D.G. The pivotal role of offloading in the management of neuropathic foot ulceration. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2005, 5, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavery, L.A.; Vela, S.A.; Lavery, D.C.; Quebedeaux, T.L. Reducing dynamic foot pressures in high-risk diabetic subjects with foot ulcerations: A comparison of treatments. Diabetes Care 1996, 19, 818–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, D.G.; Nguyen, H.C.; Lavery, L.A.; van Schie, C.H.; Boulton, A.J.; Harkless, L.B. Offloading the diabetic foot wound: A randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Care 2001, 24, 1019–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, D.G.; Lavery, L.A.; Kimbriel, H.R.; Nixon, B.P.; Boulton, A.J. Activity patterns of patients with diabetic foot ulceration: Patients with active ulceration may not adhere to a standard pressure off-loading regimen. Diabetes Care 2003, 26, 2595–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, D.G.; Lavery, L.A.; Wu, S.; Boulton, A.J. Evaluation of removable and irremovable cast walkers in the healing of diabetic foot wounds: A randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 551–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleischli, J.G.; Lavery, L.A.; Vela, S.A.; Ashry, H.; Lavery, D.C.; William, J. Stickel Bronze Award. Comparison of strategies for reducing pressure at the site of neuropathic ulcers. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 1997, 87, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eginton, M.T.; Brown, K.R.; Seabrook, G.R.; Towne, T.B.; Cambria, R.A. A prospective randomized evaluation of negative-pressure wound dressings for diabetic foot wounds. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2003, 17, 645–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veves, A.; Falanga, V.; Armstrong, D.G.; Sabolinski, M.L.; Apligraf Diabetic Foot Ulcer Study. Graftskin, a human skin equivalent, is effective in the management of noninfected neuropathic diabetic foot ulcers: A prospective randomized multicenter clinical trial. Diabetes Care 2001, 24, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmonds, M.; European and Australian Apligraf Diabetic Foot Ulcer Study Group. Apligraf in the treatment of neuropathic diabetic foot ulcers. Int. J. Low Extrem. Wounds 2009, 8, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheehan, P.; Jones, P.; Caselli, A.; Giurini, J.M.; Veves, A. Percent change in wound area of diabetic foot ulcers over a 4-week period is a robust predictor of complete healing in a 12-week prospective trial. Diabetes Care 2003, 26, 1879–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimny, S.; Schatz, H.; Pfohl, M. Determinants and estimation of healing times in diabetic foot ulcers. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2002, 16, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2016 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Blakely, M. The Use of Best Practice in the Treatment of a Complex Diabetic Foot Ulcer: A Case Report. Healthcare 2016, 4, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare4010018

Blakely M. The Use of Best Practice in the Treatment of a Complex Diabetic Foot Ulcer: A Case Report. Healthcare. 2016; 4(1):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare4010018

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlakely, Melodie. 2016. "The Use of Best Practice in the Treatment of a Complex Diabetic Foot Ulcer: A Case Report" Healthcare 4, no. 1: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare4010018