Adaptive Challenges Rising from the Life Context of African-American Caregiving Grandmothers with Diabetes: A Pilot Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Theoretical Framework

2. Methods

2.1. Sample and Setting

2.2. Recruitment

2.3. Interviews

| 1. | Tell me what it’s like to be diabetic while raising your grandchildren? |

| 2. | How has your health changed since you started raising your grandchildren? |

| 3. | Your grandchildren are_______years old. Do their ages impact how manage your diabetes? |

| 4. | How do you know if your diabetes is better or worse? |

| 5. | What doesn’t help or makes it harder to manage your diabetes since raising your grandchildren? |

| 6. | What assists you with the management of your diabetes? |

| Subsequent Interviews | |

| 1. | How has the caregiver role influenced how you check your blood sugar?

|

| 2. | How and why have these changes in self-management activities occurred? |

| 3. | What are your needs regarding checking your blood sugar? (Same self-management activities as above)? |

| 4. | Is there anything else that helps you manage your diabetes better? |

| 5. | Is there anything else that prevents you from managing your diabetes? |

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Preparation

| Month | Activity | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Interview to explore the lived experience of being diabetic and caring for grandchild | Previous study revealed that grandmothers wanted to discuss experiences as a caregiver before they were ready to discuss health. |

| 3 | Self-management interview & survey of self-management activities | Explore lived experience and identify self-management activities. |

| 5 | Provider visit followed by a focused interview with the grandmother about provider support | Observe interaction between provider & grand-mother. What topics were discussed? Was grand parenting role assessed & considered in the visit? Self-management discussed? In the interview, ask questions such as What was helpful, what was not? What were your goals for the visit? Were they met? |

| 7 | Same as month 3 | Same as month 3 with addition of asking about changes in self-management trajectory. |

| 9 | Same as month 5 | Same as month 5. |

| 11 | Same as month 3 | Same as month 7 |

| 12 | Synthesis interview | To explore any final comments and close relationship with participant |

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Scientific Rigor

Confirmability—freedom from unrecognized researcher biases

|

Dependability—the process of the study is consistent across researchers and settings

|

Credibility—authenticity and plausibility, or truth value of the results

|

Transferability—usefulness beyond the individual participants in the study

|

3. Results

3.1. Sample

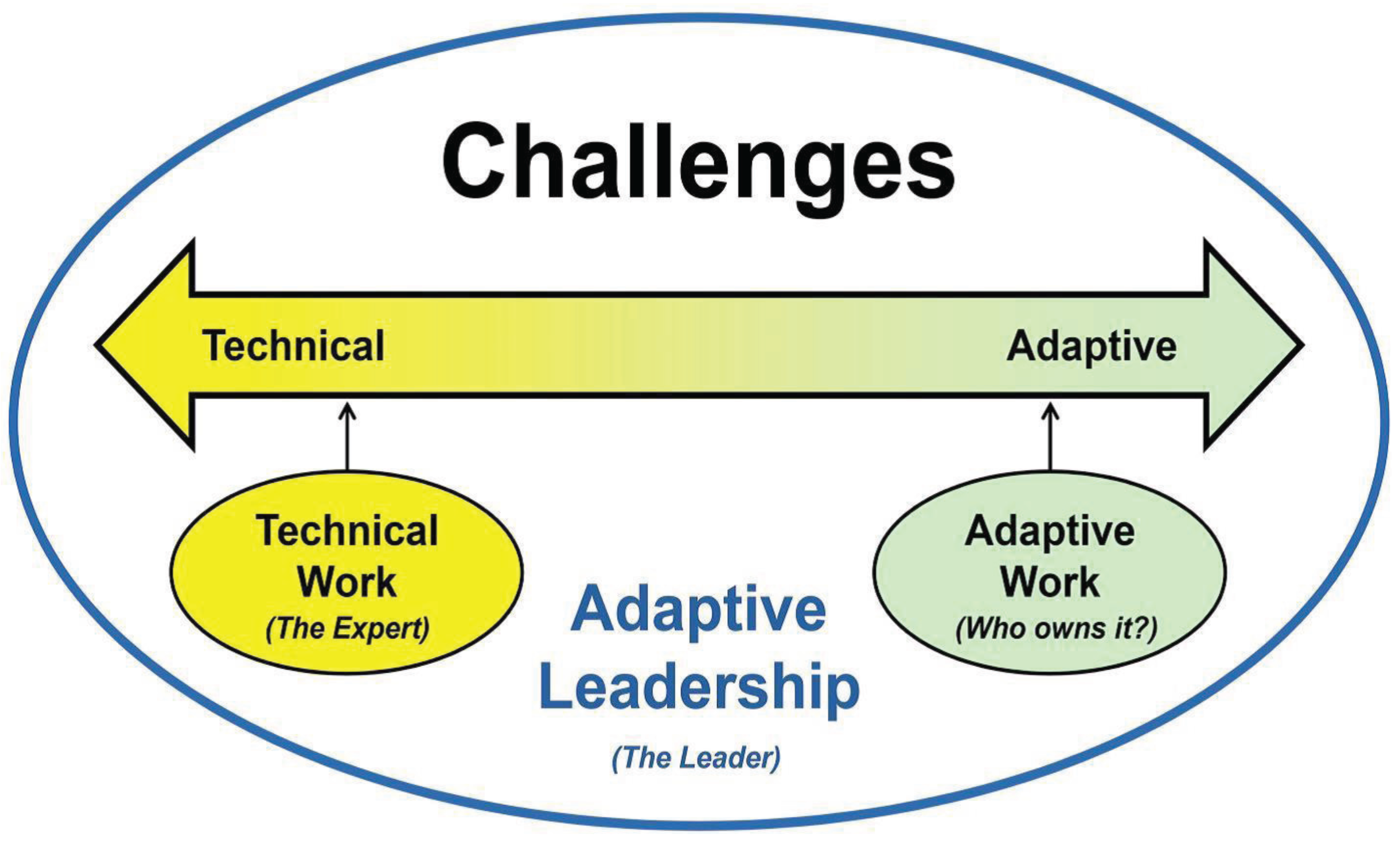

Adaptive and Technical Challenges

3.2. Adaptive Challenges

| Adaptive Challenges | Examples |

|---|---|

| Family upheaval |

|

Priority setting

|

|

| Self-silencing & self-sacrifice |

|

| Technical Challenge | Example |

| Lack of Awareness |

|

3.2.1. Family Upheaval

3.2.2. Priority Setting

3.2.2.1. Difficulties Meeting Basic Needs

3.2.2.2. Competing Demands

3.2.3. Self-Silencing and Self-Sacrifice

3.3. Technical Challenge

3.4. Feasibility Results: Establishing Trust

3.5. Limitations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey. Available online: http://factfinder2.census.gov (accessed on 19 July 2013).

- Kelley, S.J.; Whitley, D.M.; Campos, P.E. Psychological distress in African American grandmothers raising grandchildren: The contribution of child behavior problems, physical health, and family resources. Res. Nurs. Health 2013, 36, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2011. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, S11–S61. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, K. Self-care components of lifestyles: The importance of gender, attitudes and the social situation. Social Sci. Med. 1989, 29, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhl, E.; Bonsignore, P. Diabetes self-management education for older adults: General principles and practical application. Diabetes Spectr. 2006, 19, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carthron, D.L.; Johnson, T.M.; Hubbart, T.D.; Strickland, C.; Nance, K. “Give me some sugar”: The diabetes self-management activities of African-American primary caregiving grandmothers. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2010, 42, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carthron, D.L.; Bailey, D.E.; Anderson, R.A. The “invisible caregiver”: Multicaregiving among diabetic African-American grandmothers. Geriatr. Nurs. 2014, 35, S32–S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuel-Hodge, C.D.; Headen, S.W.; Skelly, A.H.; Ingram, A.F.; Keyserling, T.C.; Jackson, E.J.; Ammerman, A.S.; Elasy, T.A. Influences on day-to-day self-management of type 2 diabetes among African-American women: Spirituality, the multi-caregiving role, and other social context factors. Diabetes Care 2000, 23, 928–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallant, M.P.; Spitze, G.; Grove, J.G. Chronic illness self-care and the family lives of older adults: A synthetic review across four ethnic groups. J. Cross Cult. Gerontol. 2010, 25, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, A.R.; Peacock, N. Pleasing the masses: Messages for daily life management in African American women’s popular media sources. Am. J. Publ. Health 2011, 101, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, C.C.; Tan, P.P.; Ernandes, P.; Silverstein, M. The health of grandmothers raising grandchildren: Does the quality of family relationships matter? Fam. Syst. Health 2008, 26, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzek, A.E.; Cooney, T.M. Spousal perceptions of marital stress and support among grandparent caregivers: Variations by life stage. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2009, 68, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, A.; van der Bruggen, H.; Widdershoven, G.; Spreeuwenberg, C. Self-management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A qualitative investigation from the perspective of participants in a nurse-led, shared-care programme in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heifetz, R.A.; Grashow, A.; Linsky, M. The Practice of Adaptive Leadership: Tools and Tactics for Changing Your Organization and the World; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R.A.; Bailey, D.E.; Wu, B.; Corazzini, K.; McConnell, E.S.; Thygeson, N.M.; Docherty, S.L. Adaptive leadership framework for chronic illness: Framing a research agenda. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2015, 2, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, D.E.; Docherty, S.L.; Adams, J.A.; Carthron, D.L.; Corazzini, K.; Day, J.R.; Neglia, E.; Thygeson, M.; Anderson, R.A. Studying the clinical encounter with the adaptive leadership framework. J. Healthc. Leadersh. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, C.; Sturmberg, J. Complex adaptive chronic care. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2009, 15, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, J.; Thomson, R.; Henderson, S. Qualitative Longitudinal Research: A Discussion Paper. Available online: http://www.lsbu.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/9370/qualitative-longitudinal-research-families-working-paper.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2015).

- Durant, R.W.; Legedza, A.T.; Marcantonio, E.R.; Freeman, M.B.; Landon, B.E. Different types of distrust in clinical research among Whites and African-Americans. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2011, 103, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Speziale, H.S.; Streubert, H.J.; Carpenter, D.R. Advancing the humanistic perspective. In Qualitative Research in Nursing, 5th ed.; Lippincott Wilkins & Williams: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Friese, S. ATLAS. ti 6 User Manual. In ATLAS. ti Scientific Software Development; GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldana, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Del Bene, S.B. African American grandmothers raising grandchildren: A phenomenological perspective of marginalized women. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2010, 36, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunlap, E.; Tourigny, S.C.; Johnson, B.D. Dead tired and bone weary: Grandmothers as caregivers in drug affected inner city households. Race Soc. 2000, 3, 143–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, L.N.; Kim, C.; Ettner, S.L.; Herman, W.H.; Karter, A.J.; Beckles, G.L.; Brown, A.F. Competing demands for time and self-care behaviors, processes of care, and intermediate outcomes among people with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 1180–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods-Giscombe, C.L.; Black, A.R. Mind-body interventions to reduce risk for health disparities related to stress and “strength” among African American women: The potential of mindfulness-based stress reduction, loving kindness, and the NTU therapeutic framework. J. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2010, 15, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shouse, S.H.; Nilsson, J. Self-silencing, emotional awareness, and eating behaviors in college women. Psychol. Women Q. 2011, 35, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, D.; Kelley, S.; Campos, P. Perceptions of family empowerment in African-American custodial grandmothers raising grandchildren: Thoughts for research and practice. Fam. Soc. 2011, 92, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, G.F. Vulnerability: A conceptual model for African-American grandmother caregiving. J. Theory Constr. Test. 2006, 10, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carthron, D.; Bailey, D.E., Jr.; Anderson, R. Adaptive Challenges Rising from the Life Context of African-American Caregiving Grandmothers with Diabetes: A Pilot Study. Healthcare 2015, 3, 710-725. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare3030710

Carthron D, Bailey DE Jr., Anderson R. Adaptive Challenges Rising from the Life Context of African-American Caregiving Grandmothers with Diabetes: A Pilot Study. Healthcare. 2015; 3(3):710-725. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare3030710

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarthron, Dana, Donald E. Bailey, Jr., and Ruth Anderson. 2015. "Adaptive Challenges Rising from the Life Context of African-American Caregiving Grandmothers with Diabetes: A Pilot Study" Healthcare 3, no. 3: 710-725. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare3030710