Geographic Prevalence and Mix of Regional Cuisines in Chinese Cities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

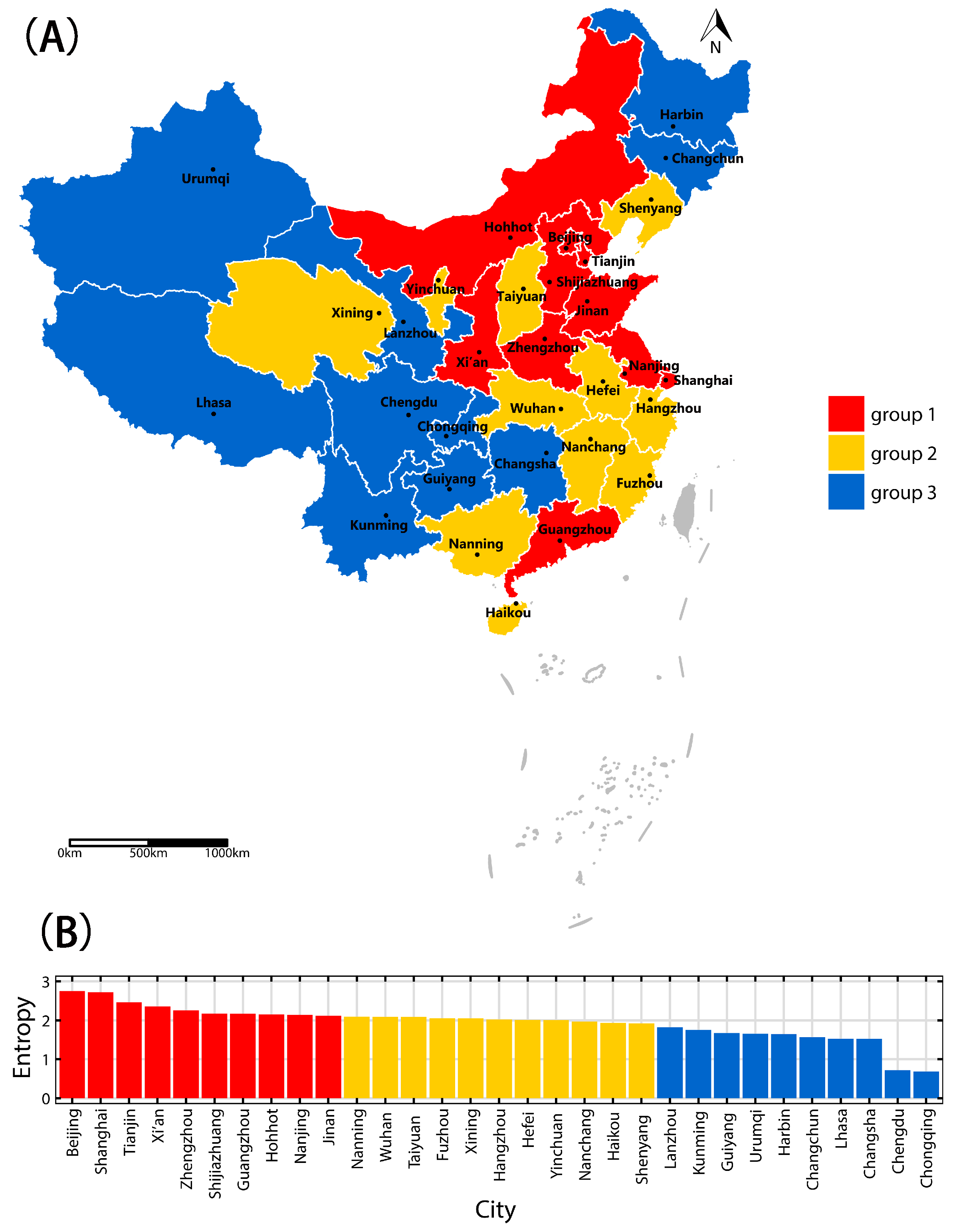

- By classifying restaurants based on regional Chinese cuisines and other culinary styles, we measure the diversity of restaurants by city, and analyze how cities with a different diversity of restaurants that serve regional Chinese cuisines are geographically distributed.

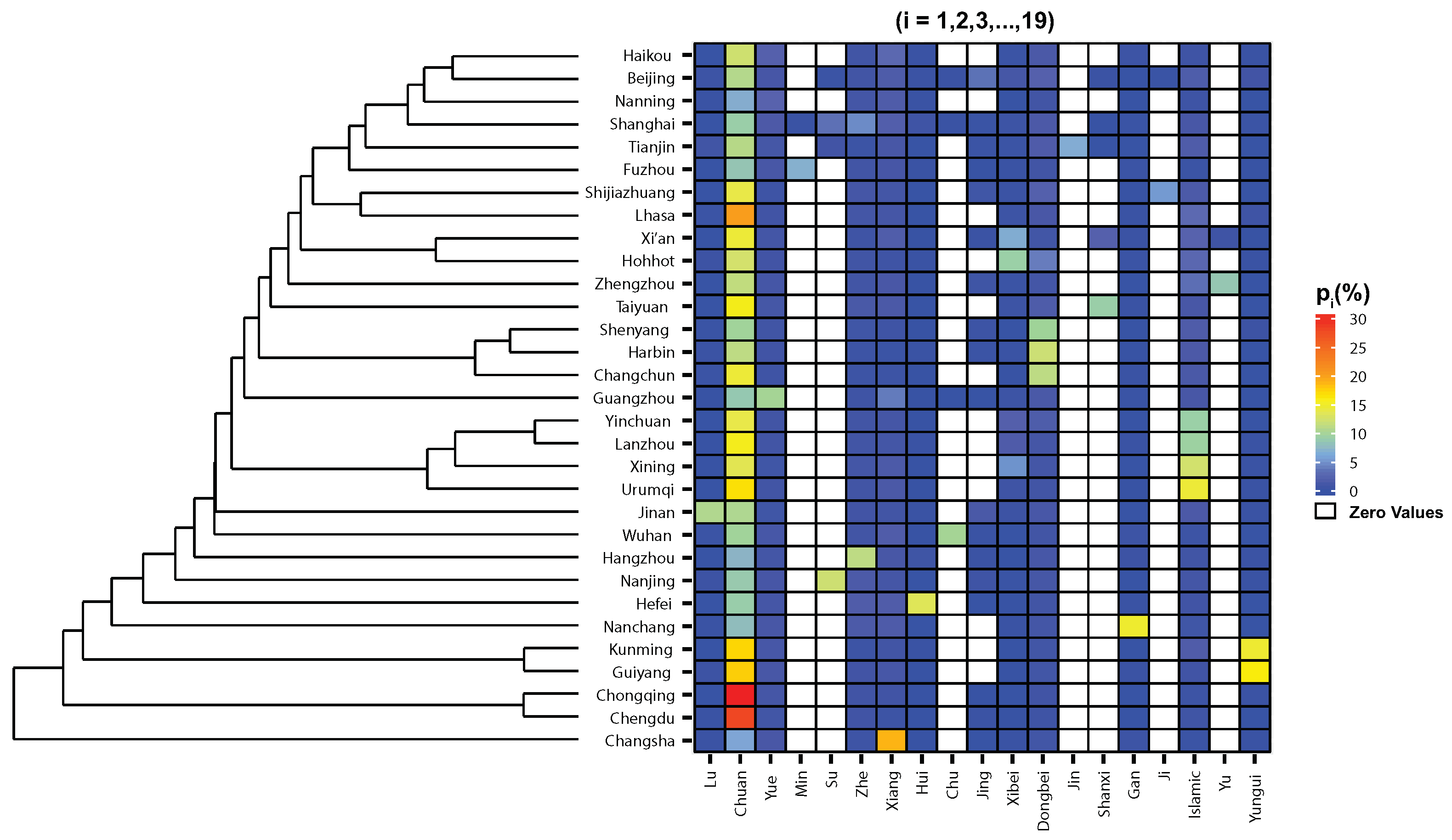

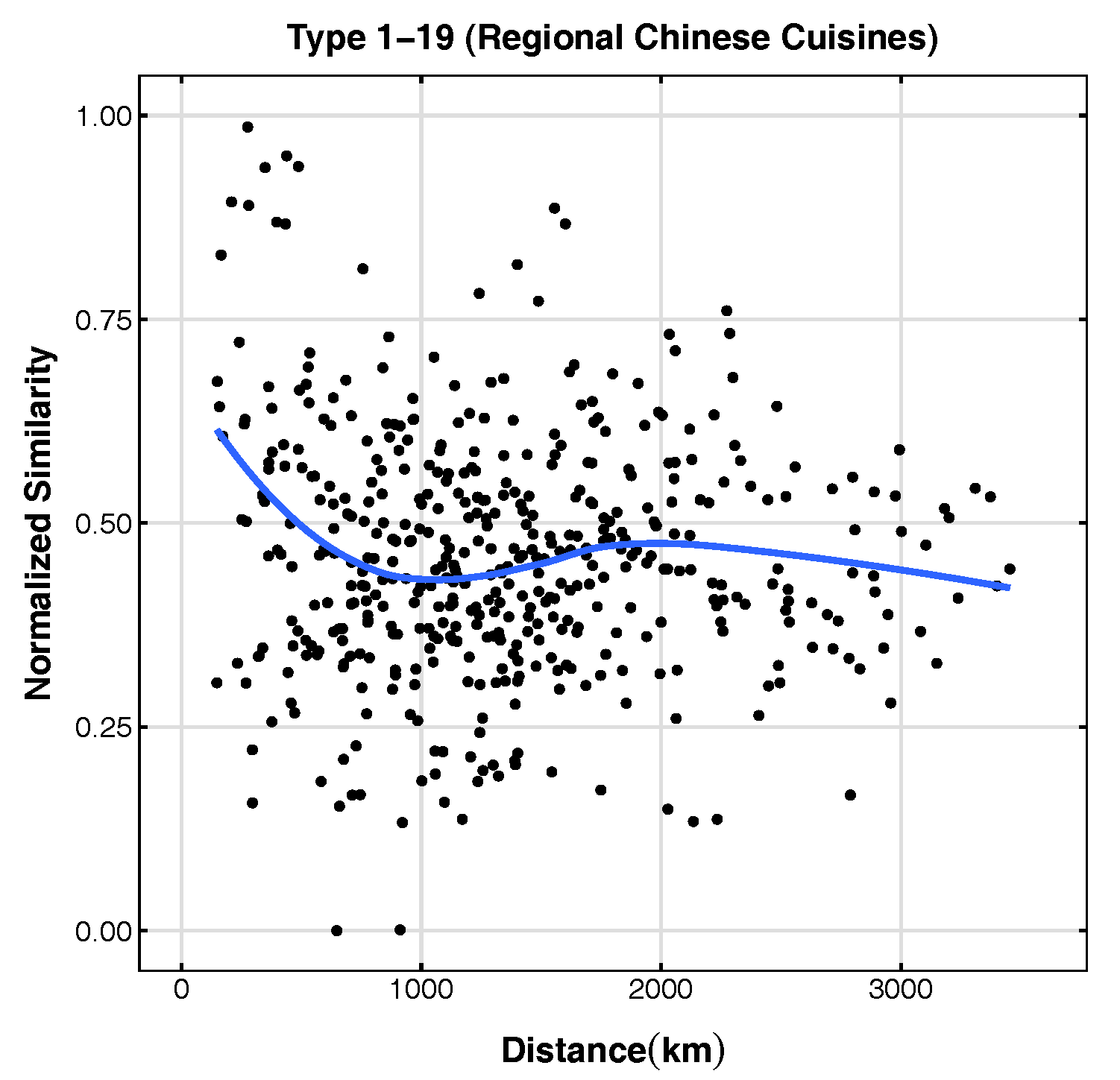

- We further examine each individual city to generate the percentage of restaurants by type, and apply a hierarchical clustering algorithm to explore the similarities of consumers’ dining options among these cities. We then examine how the similarities are related to geographic distance.

- By associating each regional Chinese cuisine to its origin, we introduce a weighted distance measure to quantify its geographic prevalence. The distance measure is able to distinguish the cuisine types that spread across various cities in China from those that exhibit strong local characteristics.

- For the restaurants in each individual city, we further analyze consumers’ ratings on taste to gain insights into their dining preferences. A popularity index based on location quotient is developed to examine whether certain regional Chinese cuisines dominate among the top-tier restaurants in a city.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Food, Consumption, and Urban Culinary Scene

2.2. The Evolving Urban Culinary Scene in China

2.3. Exploring Urban Dynamics with User-Generated Content

3. Study Area and Data Set

4. Diversity of Restaurants and Similarities between Cities

4.1. Reclassification of Restaurants

4.2. Diversity of Restaurants by City

4.3. Similarities between Cities

5. Geographic Prevalence of Regional Chinese Cuisines

6. Characterizing Top-Tier Restaurants in Cities by Cuisine Type

7. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1.

| City Names | Lu | Chuan | Yue | Min | Su | Zhe | Xiang | Hui | Chu | Jing | Xibei | Dongbei | Jin | Shanxi | Gan | Ji | Halal | Yu | Yungui |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 1.36 | 44.30 | 3.71 | 0.00 | 0.87 | 2.41 | 6.88 | 0.65 | 0.60 | 14.72 | 3.88 | 9.33 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 0.40 | 0.47 | 7.59 | 0.00 | 2.15 |

| Changchun | 0.74 | 50.83 | 1.28 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.04 | 1.15 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 39.82 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 4.40 | 0.00 | 0.35 |

| Changsha | 0.56 | 22.93 | 3.97 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.69 | 65.97 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.31 | 0.18 | 2.57 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.89 | 0.00 | 0.68 | 0.00 | 0.15 |

| Chengdu | 0.16 | 90.61 | 2.39 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.48 | 1.03 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.52 | 0.07 | 1.26 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 1.83 | 0.00 | 0.34 |

| Chongqing | 0.29 | 91.13 | 2.55 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.37 | 1.42 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 1.39 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 0.83 | 0.00 | 0.48 |

| Fuzhou | 0.38 | 43.96 | 5.24 | 36.03 | 0.00 | 3.43 | 4.67 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.23 | 3.22 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.09 | 0.00 | 1.15 | 0.00 | 0.18 |

| Guangzhou | 0.16 | 33.23 | 38.47 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.39 | 15.49 | 0.11 | 0.40 | 0.34 | 1.04 | 4.74 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.45 | 0.00 | 3.79 | 0.00 | 0.40 |

| Guiyang | 0.35 | 46.50 | 2.63 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.31 | 2.90 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 1.92 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 1.22 | 0.00 | 42.54 |

| Haikou | 0.32 | 59.90 | 10.96 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.66 | 14.65 | 0.28 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.11 | 6.47 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.63 | 0.00 | 1.79 | 0.00 | 0.24 |

| Hangzhou | 0.37 | 31.96 | 3.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 48.95 | 4.35 | 1.84 | 0.00 | 0.71 | 0.27 | 4.75 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.57 | 0.00 | 2.32 | 0.00 | 0.66 |

| Harbin | 0.57 | 43.23 | 1.61 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.07 | 0.87 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.75 | 0.21 | 46.17 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 4.95 | 0.00 | 0.28 |

| Hefei | 0.30 | 32.09 | 2.96 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 6.33 | 6.28 | 47.17 | 0.00 | 0.30 | 0.14 | 2.44 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 1.59 | 0.00 | 0.21 |

| Hohhot | 0.42 | 40.75 | 1.51 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.75 | 1.31 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 29.98 | 13.76 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.76 | 0.00 | 9.44 | 0.00 | 0.16 |

| Jinan | 39.56 | 39.08 | 2.45 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.75 | 2.31 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 4.71 | 0.47 | 4.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 4.82 | 0.00 | 0.16 |

| Kunming | 0.17 | 46.72 | 2.98 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.88 | 1.96 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.28 | 2.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 4.84 | 0.00 | 39.87 |

| Lanzhou | 0.12 | 51.68 | 2.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.04 | 2.65 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.54 | 2.92 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 32.58 | 0.00 | 0.15 |

| Lhasa | 0.89 | 73.10 | 1.62 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.91 | 2.99 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.05 | 3.96 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 11.71 | 0.00 | 1.37 |

| Nanchang | 0.20 | 28.26 | 3.53 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.90 | 5.60 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 2.74 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 51.74 | 0.00 | 2.28 | 0.00 | 0.33 |

| Nanjing | 0.50 | 33.10 | 3.37 | 0.00 | 45.44 | 5.23 | 3.17 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 1.39 | 0.43 | 3.60 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.35 | 0.00 | 2.90 | 0.00 | 0.18 |

| Nanning | 0.39 | 52.04 | 19.34 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.91 | 13.11 | 0.32 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.45 | 4.63 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.61 | 0.00 | 2.67 | 0.00 | 0.55 |

| Shanghai | 0.37 | 37.18 | 5.77 | 0.22 | 14.38 | 19.53 | 8.29 | 1.66 | 0.17 | 0.48 | 1.20 | 5.22 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.49 | 0.00 | 4.16 | 0.00 | 0.80 |

| Shenyang | 0.48 | 41.33 | 2.43 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.74 | 1.67 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 1.24 | 0.35 | 41.56 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.31 | 0.00 | 7.22 | 0.00 | 0.52 |

| Shijiazhuang | 0.39 | 52.87 | 1.81 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.10 | 2.99 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 2.45 | 0.57 | 8.47 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 20.92 | 5.64 | 0.00 | 0.40 |

| Taiyuan | 0.23 | 48.49 | 3.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.80 | 4.31 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.90 | 5.42 | 0.00 | 29.77 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 3.35 | 0.00 | 0.29 |

| Tianjin | 2.17 | 43.51 | 3.73 | 0.00 | 1.96 | 1.36 | 3.90 | 0.31 | 0.00 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 6.59 | 26.78 | 0.40 | 0.27 | 0.00 | 6.74 | 0.00 | 0.40 |

| Urumqi | 0.19 | 47.66 | 1.94 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.97 | 3.79 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.05 | 1.92 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 41.25 | 0.00 | 0.12 |

| Wuhan | 0.85 | 39.13 | 4.34 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.78 | 7.05 | 0.12 | 40.06 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 2.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.31 | 0.00 | 1.14 | 0.00 | 0.37 |

| Xi’an | 0.24 | 47.01 | 2.49 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.21 | 6.21 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.48 | 22.19 | 2.43 | 0.00 | 7.40 | 0.46 | 0.00 | 8.30 | 1.33 | 0.12 |

| Xining | 0.07 | 38.87 | 1.88 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.27 | 4.00 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 14.66 | 2.19 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.29 | 0.00 | 35.57 | 0.00 | 0.12 |

| Yinchuan | 0.26 | 47.18 | 2.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.10 | 2.78 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 7.42 | 6.23 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 31.48 | 0.00 | 0.23 |

| Zhengzhou | 0.21 | 41.44 | 2.95 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.40 | 3.98 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 1.54 | 0.76 | 2.77 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.32 | 0.00 | 12.40 | 30.80 | 0.31 |

Appendix A.2.

| City Name | Pair-Wise Correlation | City Name | Pair-Wise Correlation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.999 | Lhasa | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 |

| Changchun | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | Nanchang | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 |

| Changsha | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | Nanjing | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 |

| Chengdu | 0.998 | 0.999 | 0.999 | Nanning | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 |

| Chongqing | 0.998 | 0.999 | 0.999 | Shanghai | 0.997 | 0.998 | 0.999 |

| Fuzhou | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | Shenyang | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 |

| Guangzhou | 0.998 | 0.999 | 0.999 | Shijiazhuang | 0.998 | 0.999 | 1.000 |

| Guiyang | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | Taiyuan | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 |

| Haikou | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | Tianjin | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 |

| Hangzhou | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.999 | Urumqi | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 |

| Harbin | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | Wuhan | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 |

| Hefei | 0.999 | 0.999 | 1.000 | Xi’an | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 |

| Hohhot | 0.999 | 0.999 | 1.000 | Xining | 0.999 | 0.999 | 1.000 |

| Jinan | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | Yinchuan | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 |

| Kunming | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | Zhengzhou | 0.999 | 0.999 | 1.000 |

| Lanzhou | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | ||||

Appendix A.3.

| City Name | Q1 Mean/Median | Q2 Mean/Median | Q3 Mean/Median | Q4 Mean/Median | Q5 Mean/Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 8.8/8.9 | 7.8/7.7 | 7.3/7.3 | 7.1/7.0 | 6.7/6.8 |

| Changchun | 8.2/8.0 | 7.5/7.5 | 7.2/7.2 | 7.0/7.0 | 6.7/6.8 |

| Changsha | 8.4/8.3 | 7.7/7.7 | 7.4/7.3 | 7.1/7.1 | 6.8/6.9 |

| Chengdu | 8.4/8.3 | 7.6/7.6 | 7.3/7.3 | 7.0/7.0 | 6.7/6.8 |

| Chongqing | 8.3/8.2 | 7.6/7.6 | 7.3/7.3 | 7.1/7.0 | 6.7/6.8 |

| Fuzhou | 8.3/8.2 | 7.6/7.6 | 7.2/7.2 | 7.0/7.0 | 6.7/6.8 |

| Guangzhou | 8.4/8.4 | 7.6/7.6 | 7.2/7.2 | 7.0/7.0 | 6.6/6.7 |

| Guiyang | 8.0/7.8 | 7.4/7.4 | 7.1/7.1 | 6.9/6.9 | 6.6/6.7 |

| Haikou | 8.2/8.0 | 7.6/7.6 | 7.3/7.3 | 7.1/7.1 | 6.7/6.8 |

| Hangzhou | 8.7/8.7 | 7.7/7.7 | 7.3/7.3 | 7.0/7.0 | 6.7/6.8 |

| Harbin | 8.3/8.1 | 7.5/7.5 | 7.2/7.2 | 7.0/7.0 | 6.7/6.8 |

| Hefei | 8.7/8.7 | 7.7/7.7 | 7.4/7.3 | 7.1/7.1 | 6.8/6.8 |

| Hohhot | 8.2/8.0 | 7.6/7.6 | 7.2/7.2 | 7.0/7.0 | 6.8/6.9 |

| Jinan | 8.4/8.4 | 7.6/7.6 | 7.2/7.2 | 7.0/7.0 | 6.7/6.8 |

| Kunming | 8.2/8.1 | 7.5/7.5 | 7.2/7.2 | 7.0/7.0 | 6.7/6.8 |

| Lanzhou | 8.1/7.9 | 7.5/7.5 | 7.2/7.2 | 7.0/7.0 | 6.6/6.8 |

| Lhasa | 7.9/7.7 | 7.4/7.4 | 7.1/7.1 | 7.0/7.0 | 6.6/6.8 |

| Nanchang | 8.4/8.3 | 7.6/7.6 | 7.3/7.3 | 7.0/7.0 | 6.7/6.8 |

| Nanjing | 8.8/8.8 | 7.8/7.7 | 7.4/7.3 | 7.1/7.1 | 6.7/6.8 |

| Nanning | 7.9/7.8 | 7.4/7.3 | 7.1/7.1 | 6.9/6.9 | 6.5/6.4 |

| Shanghai | 8.7/8.7 | 7.7/7.7 | 7.3/7.3 | 7.0/7.0 | 6.6/6.7 |

| Shenyang | 8.6/8.5 | 7.6/7.6 | 7.3/7.3 | 7.0/7.0 | 6.7/6.8 |

| Shijiazhuang | 8.6/8.5 | 7.7/7.7 | 7.4/7.4 | 7.1/7.1 | 6.7/6.8 |

| Taiyuan | 8.3/8.2 | 7.6/7.6 | 7.3/7.3 | 7.0/7.0 | 6.7/6.8 |

| Tianjin | 8.7/8.7 | 7.7/7.7 | 7.3/7.3 | 7.1/7.0 | 6.7/6.8 |

| Urumqi | 8.3/8.3 | 7.6/7.6 | 7.3/7.3 | 7.0/7.0 | 6.7/6.8 |

| Wuhan | 8.7/8.7 | 7.7/7.6 | 7.3/7.3 | 7.0/7.0 | 6.7/6.8 |

| Xi’an | 8.5/8.4 | 7.6/7.6 | 7.3/7.3 | 7.0/7.0 | 6.7/6.8 |

| Xining | 8.0/7.8 | 7.4/7.4 | 7.2/7.2 | 7.0/7.0 | 6.7/6.8 |

| Yinchuan | 8.4/8.3 | 7.6/7.6 | 7.3/7.3 | 7.1/7.1 | 6.7/6.8 |

| Zhengzhou | 8.4/8.4 | 7.7/7.7 | 7.3/7.3 | 7.1/7.0 | 6.7/6.8 |

References

- Morrison, K.T.; Nelson, T.A.; Ostry, A.S. Mapping spatial variation in food consumption. Appl. Geogr. 2011, 31, 1262–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yue, T.; Wang, C.; Fan, Z.; Liu, X. Spatial-temporal variations of food provision in China. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2012, 13, 1933–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, Z.P. Culinary deserts, gastronomic oases: A classification of US cities. Urban Stud. 2006, 43, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. Featured graphic. Visualizing urban gastronomy in China. Environ. Plan. A 2014, 46, 1012–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalis, M.H.; Che, D.; Markwell, K. Utilising local cuisine to market Malaysia as a tourist destination. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 144, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyne, S.; Hall, D.; Williams, F. Policy, support and promotion for food-related tourism initiatives: A marketing approach to regional development. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2003, 14, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, C. Food and Gastronomy for Sustainable Place Development: A Multidisciplinary Analysis of Different Theoretical Approaches. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.D. Obesity and the Role of Food Marketing: A Policy Analysis of Issues and Remedies. J. Public Policy Mark. 2004, 23, 153–169. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Song, Y.; Wu, K.; Wang, J.; Li, D.; Long, Y. Understanding urban China with open data. Cities 2015, 47, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, I.; Crang, P. The world on a plate: Culinary culture, displacement and geographical knowledges. J. Mat. Cult. 1996, 1, 131–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhi, F.; Ostberg, J.; Bengtsson, A. Negotiating cultural boundaries: Food, travel and consumer identities. Consum. Mark. Cult. 2010, 13, 133–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askegaard, S.; Kjeldgaard, D. Here, there, and everywhere: Place branding and gastronomical globalization in a macromarketing perspective. J. Macromark. 2007, 27, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrer, J. Eating the West and Beating the Rest: Culinary Occidentalism and Urban Soft Power in Asia’s Global Food Cities. Available online: http://icc.fla.sophia.ac.jp/global%20food%20papers/pdf/2_3_FARRER.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2010).

- Caspi, C.E.; Sorensen, G.; Subramanian, S.; Kawachi, I. The local food environment and diet: A systematic review. Health Place 2012, 18, 1172–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mak, A.H.; Lumbers, M.; Eves, A. Globalisation and food consumption in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 171–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carroll, G.R.; Torfason, M.T. Restaurant Organizational Forms and Community in the US in 2005. City Commun. 2011, 10, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, P.R.; Inglehart, R.F. Value Change in Global Perspective; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mullins, P.; Natalier, K.; Smith, P.; Smeaton, B. Cities and consumption spaces. Urban Aff. Rev. 1999, 35, 44–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zukin, S. Urban lifestyles: Diversity and standardisation in spaces of consumption. Urban Stud. 1998, 35, 825–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K. Ethnic Foodscapes: Foreign Cuisines in the United States. Food Cult. Soc. 2017, 20, 365–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.L.; Kolko, J.; Saiz, A. Consumer city. J. Econ. Geogr. 2001, 1, 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiff, N. Cities and product variety: Evidence from restaurants. J. Econ. Geogr. 2014, 15, 1085–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Irala-Estevez, J.; Groth, M.; Johansson, L.; Oltersdorf, U.; Prättälä, R.; Martínez-González, M.A. A systematic review of socio-economic differences in food habits in Europe: Consumption of fruit and vegetables. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 54, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, C.; Singer, P.; Strohmaier, M. The nature and evolution of online food preferences. EPJ Data Sci. 2014, 3, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.Y.; Ahnert, S.E.; Bagrow, J.P.; Barabási, A.L. Flavor network and the principles of food pairing. Sci. Rep. 2011, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Y.; Li, D.; Liu, X. How block density and typology affect urban vitality: an exploratory analysis in Shenzhen, China. Urban Geogr. 2017, 39, 631–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X. Modern Food Culture Geography Research in Sichuan and Chongqing Region. Master’s Thesis, Southwest University, Chongqing, China, 2014. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J. The geographical environment factors on Chinese Eight Cuisines Formation. Yinshan Acad. J. 2016. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wu, W.; Yao, L.; Bai, Y.; Xiong, G. Transnational practices in urban China: Spatiality and localization of western fast food chains. Habitat Int. 2014, 43, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Web 2.0. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Web_2.0 (accessed on 2 February 2017).

- Krishnamurthy, B.; Gill, P.; Arlitt, M. A few chirps about twitter. In Proceedings of the First Workshop on Online Social Networks, ACM, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–22 August 2008; pp. 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.; Novak, J.; Tomkins, A. Structure and Evolution of Online Social Networks. In Link Mining: Models, Algorithms, and Applications; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 337–357. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, J.; Lim, E.P.; Jiang, J.; He, Q. Twitterrank: Finding topic-sensitive influential twitterers. In Proceedings of the Third ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, ACM, New York, NY, USA, 3–6 February 2010; pp. 261–270. [Google Scholar]

- Zook, M.; Graham, M.; Shelton, T.; Gorman, S. Volunteered geographic information and crowdsourcing disaster relief: A case study of the Haitian earthquake. World Med. Health Policy 2010, 2, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodchild, M.F.; Glennon, J.A. Crowdsourcing geographic information for disaster response: A research frontier. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2010, 3, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Longueville, B.; Smith, R.S.; Luraschi, G. Omg, from here, I can see the flames!: A use case of mining location based social networks to acquire spatio-temporal data on forest fires. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Workshop on Location Based Social Networks, ACM, Seattle, WA, USA, 3 November 2009; pp. 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hawelka, B.; Sitko, I.; Beinat, E.; Sobolevsky, S.; Kazakopoulos, P.; Ratti, C. Geo-located Twitter as proxy for global mobility patterns. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2014, 41, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frias-Martinez, V.; Soto, V.; Hohwald, H.; Frias-Martinez, E. Characterizing urban landscapes using geolocated tweets. In Proceedings of the IEEE Privacy, Security, Risk and Trust (PASSAT), 2012 International Conference on and 2012 International Confernece on Social Computing (SocialCom), Washington, DC, USA, 3–5 September 2012; pp. 239–248. [Google Scholar]

- Wakamiya, S.; Lee, R.; Sumiya, K. Urban area characterization based on semantics of crowd activities in twitter. In Proceedings of the International Conference on GeoSpatial Sematics, Brest, France, 12–13 May 2011; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 108–123. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Yang, X. Does food environment influence food choices? A geographical analysis through “tweets”. Appl. Geogr. 2014, 51, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widener, M.J.; Li, W. Using geolocated Twitter data to monitor the prevalence of healthy and unhealthy food references across the US. Appl. Geogr. 2014, 54, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbar, S.; Mejova, Y.; Weber, I. You tweet what you eat: Studying food consumption through twitter. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, ACM, Seoul, Korea, 18–23 April 2015; pp. 3197–3206. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.X.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Z.K.; Zhang, Q.M.; Zhou, T.; Ahn, Y.Y. Geography and similarity of regional cuisines in China. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bessière, J. Local development and heritage: Traditional food and cuisine as tourist attractions in rural areas. Sociol. Rural. 1998, 38, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Yuan, N.J.; Zheng, K.; Lian, D.; Xie, X.; Rui, Y. Exploiting dining preference for restaurant recommendation. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on World Wide Web, International World Wide Web Conferences Steering Committee, Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–15 April 2016; pp. 725–735. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, I.H.S.; Lau, V.P.; Lo, T.W.C.; Sha, Z.; Yun, H. Service quality in restaurant operations in China: Decision-and experiential-oriented perspectives. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 26, 698–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- About Dianping. Available online: http://www.dianping.com/aboutus (accessed on 2 February 2017).

- Chinese Cuisine. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_cuisine (accessed on 2 February 2017).

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. ACM Sigmob Mob. Comput. Commun. Rev. 2001, 5, 3–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese Economic Reform. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_economic_reform (accessed on 2 February 2017).

- Wang, X.; Cai, D.; Hoogmoed, W.; Oenema, O.; Perdok, U. Developments in conservation tillage in rainfed regions of North China. Soil Tillage Res. 2007, 93, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, E.H. Measurement of diversity. Nature 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Pei, J.; Kamber, M. Data Mining: Concepts and Techniques; Elsevier: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, K.R.; McCluskey, J.J.; Wahl, T.I. Consumer preferences for western-style convenience foods in China. China Econ. Rev. 2007, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möhring, M. Transnational Food Migration and the Internalization of Food Consumption: Ethnic Cuisine in West Germany. In Food and Globalization: Consumption, Markets and Politics in the Modern World; Berg Publisher: Oxford, UK, 2008; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X. Take the edge off: A hybrid geographic food access measure. Appl. Geogr. 2017, 87, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotheringham, A.S.; Wong, D.W. The modifiable areal unit problem in multivariate statistical analysis. Environ. Plan. A 1991, 23, 1025–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Unique Id | Cuisine Type or Culinary Style | Origin of Cuisine (or Major Characteristics) | % of Restaurants |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lu (鲁) | Shandong province | 0.44 |

| 2 | Chuan (川) | Sichuan province and Chongqing municipality | 13.78 |

| 3 | Yue (粤) | Guangdong province | 1.51 |

| 4 | Min (闽) | Fujian province | 0.17 |

| 5 | Su (苏) | Jiangsu province | 0.88 |

| 6 | Zhe (浙) | Zhejiang province | 1.46 |

| 7 | Xiang (湘) | Hunan province | 1.86 |

| 8 | Hui (徽) | Anhui province | 0.44 |

| 9 | Chu (楚) | Hubei province | 0.45 |

| 10 | Jing (京) | Beijing municipality | 0.57 |

| 11 | Xibei (西北) | Northwest China including Shaanxi (“陕西”) province, Gansu province, Qinghai province, Ningxia, and Xinjiang | 0.72 |

| 12 | Dongbei (东北) | Northeast China including Heilongjiang Province, Jilin Province, Liaoning province, and Inner Mongolia | 2.23 |

| 13 | Jin (津) | Tianjin municipality | 0.30 |

| 14 | Shanxi (山西) | Shanxi province | 0.28 |

| 15 | Gan (赣) | Jiangxi province | 0.35 |

| 16 | Ji (冀) | Hebei province | 0.14 |

| 17 | Islamic (清真) | The cuisine originally comes from other Islamic countries (e.g., Iran) and gradually becomes popular in northwestern China (e.g., Xinjiang, Qinghai and Gansu province). | 1.62 |

| 18 | Yu (豫) | Henan province | 0.31 |

| 19 | Yungui (云贵) | Yunnan province and Guizhou province | 0.71 |

| 20 | Fast Food | Food that is prepared and served quickly | 17.36 |

| 21 | Street Food (小吃) | A generic type which encompasses different types of street food (e.g., noodles, steamed buns, dumplings) | 14.95 |

| 22 | Barbecue | A popular culinary style in China with signature dishes such as grills and barbecues | 5.08 |

| 23 | Dessert/Coffee | Restaurants which mainly serve coffee and desserts (e.g., Starbucks) | 18.78 |

| 24 | Foreign | Cuisine types which do not originate from China (e.g., Japanese Food, South Korean Dish) | 4.58 |

| 25 | Others | Other Chinese cuisine types or culinary styles with each accounting for less than 0.1% of total restaurants. | 11.03 |

| City Name | Percentage of Restaurants in City (** Indicates Local Cuisine Type) | Total | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cuisine 1 | Cuisine 2 | Cuisine 3 | Cuisine 4 | Cuisine 5 | |||||||

| Beijing | Chuan | 44.3 | Jing ** | 14.7 | Dongbei | 9.3 | Islamic | 7.6 | Xiang | 6.9 | 82.8 |

| Changchun | Chuan | 50.8 | Dongbei ** | 39.8 | Islamic | 4.4 | Yue | 1.3 | Xiang | 1.2 | 97.5 |

| Changsha | Xiang ** | 66.0 | Chuan | 22.9 | Yue | 4.0 | Dongbei | 2.6 | Zhe | 1.7 | 97.1 |

| Chengdu | Chuan ** | 90.6 | Yue | 2.4 | Islamic | 1.8 | Zhe | 1.5 | Dongbei | 1.3 | 97.6 |

| Chongqing | Chuan ** | 91.1 | Yue | 2.5 | Xiang | 1.4 | Dongbei | 1.4 | Zhe | 1.4 | 97.9 |

| Fuzhou | Chuan | 44.0 | Min ** | 36.0 | Yue | 5.2 | Xiang | 4.7 | Zhe | 3.4 | 93.3 |

| Guangzhou | Yue ** | 38.5 | Chuan | 33.2 | Xiang | 15.5 | Dongbei | 4.7 | Islamic | 3.8 | 95.7 |

| Guiyang | Chuan | 46.5 | Yungui ** | 42.5 | Xiang | 2.9 | Yue | 2.6 | Dongbei | 1.9 | 96.5 |

| Haikou | Chuan | 59.9 | Xiang | 14.6 | Yue | 11.0 | Dongbei | 6.5 | Zhe | 2.7 | 94.6 |

| Hangzhou | Zhe ** | 49.0 | Chuan | 32.0 | Dongbei | 4.7 | Xiang | 4.3 | Yue | 3.3 | 93.3 |

| Harbin | Dongbei ** | 46.2 | Chuan | 43.2 | Islamic | 5.0 | Yue | 1.6 | Zhe | 1.1 | 97.0 |

| Hefei | Hui ** | 47.2 | Chuan | 32.1 | Zhe | 6.3 | Xiang | 6.3 | Yue | 3.0 | 94.8 |

| Hohhot | Chuan | 40.7 | Xibei | 30.0 | Dongbei | 13.8 | Islamic | 9.4 | Zhe | 1.7 | 95.7 |

| Jinan | Lu ** | 39.6 | Chuan | 39.1 | Islamic | 4.8 | Jing | 4.7 | Dongbei | 4.2 | 92.4 |

| Kunming | Chuan | 46.7 | Yungui ** | 39.9 | Islamic | 4.8 | Yue | 3.0 | Dongbei | 2.0 | 96.4 |

| Lanzhou | Chuan | 51.7 | Islamic | 32.6 | Xibei ** | 5.5 | Dongbei | 2.9 | Xiang | 2.6 | 95.4 |

| Lhasa | Chuan | 73.1 | Islamic | 11.7 | Dongbei | 4.0 | Xiang | 3.0 | Zhe | 2.9 | 94.7 |

| Nanchang | Gan ** | 51.7 | Chuan | 28.3 | Xiang | 5.6 | Zhe | 4.9 | Yue | 3.5 | 94.0 |

| Nanjing | Su ** | 45.4 | Chuan | 33.1 | Zhe | 5.2 | Dongbei | 3.6 | Yue | 3.4 | 90.7 |

| Nanning | Chuan | 52.0 | Yue | 19.3 | Xiang | 13.1 | Zhe | 5.9 | Dongbei | 4.6 | 95.0 |

| Shanghai | Chuan | 37.2 | Zhe | 19.5 | Su | 14.4 | Xiang | 8.3 | Yue | 5.8 | 85.1 |

| Shenyang | Dongbei ** | 41.6 | Chuan | 41.3 | Islamic | 7.2 | Zhe | 2.7 | Yue | 2.4 | 95.3 |

| Shijiazhuang | Chuan | 52.9 | Ji ** | 20.9 | Dongbei | 8.5 | Islamic | 5.6 | Zhe | 3.1 | 91.0 |

| Taiyuan | Chuan | 48.5 | Shanxi ** | 29.8 | Dongbei | 5.4 | Xiang | 4.3 | Zhe | 3.8 | 91.8 |

| Tianjin | Chuan | 43.5 | Jin ** | 26.8 | Islamic | 6.7 | Dongbei | 6.6 | Xiang | 3.9 | 87.5 |

| Urumqi | Chuan | 47.7 | Islamic ** | 41.3 | Xiang | 3.8 | Zhe | 2.0 | Yue | 1.9 | 96.6 |

| Wuhan | Chu ** | 40.1 | Chuan | 39.1 | Xiang | 7.0 | Yue | 4.3 | Zhe | 2.8 | 93.4 |

| Xi’an | Chuan | 47.0 | Xibei ** | 22.2 | Islamic | 8.3 | Shanxi | 7.4 | Xiang | 6.2 | 91.1 |

| Xining | Chuan | 38.9 | Islamic | 35.6 | Xibei ** | 14.7 | Xiang | 4.0 | Zhe | 2.3 | 95.4 |

| Yinchuan | Chuan | 47.2 | Islamic | 31.5 | Xibei ** | 7.4 | Dongbei | 6.2 | Xiang | 2.8 | 95.1 |

| Zhengzhou | Chuan | 41.4 | Yu ** | 30.8 | Islamic | 12.4 | Xiang | 4.0 | Yue | 3.0 | 91.6 |

| City Name | Name of Cuisines and Corresponding Index (** Indicates Local Cuisine Type) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing | Chuan | 1.58 | Xiang | 1.17 | Islamic | 1.06 | Dongbei | 0.77 | Jing ** | 0.47 |

| Changchun | Yue | 1.72 | Chuan | 1.29 | Xiang | 1.14 | Islamic | 0.88 | Dongbei ** | 0.68 |

| Changsha | Xiang ** | 1.10 | Chuan | 0.94 | Yue | 0.90 | Dongbei | 0.61 | Zhe | 0.20 |

| Chengdu | Chuan ** | 1.07 | Yue | 0.71 | Islamic | 0.50 | Dongbei | 0.31 | Zhe | 0.32 |

| Chongqing | Chuan ** | 1.05 | Yue | 0.86 | Xiang | 0.56 | Dongbei | 0.42 | Zhe | 0.28 |

| Fuzhou | Chuan | 1.36 | Yue | 1.25 | Xiang | 1.25 | Min ** | 0.72 | Zhe | 0.55 |

| Guangzhou | Yue ** | 1.31 | Chuan | 1.03 | Xiang | 0.71 | Dongbei | 0.52 | Islamic | 0.40 |

| Guiyang | Yue | 1.34 | Chuan | 1.10 | Yungui ** | 0.99 | Xiang | 0.71 | Dongbei | 0.52 |

| Haikou | Chuan | 1.10 | Yue | 1.05 | Xiang | 1.02 | Dongbei | 0.97 | Zhe | 0.39 |

| Hangzhou | Chuan | 1.15 | Zhe ** | 1.11 | Yue | 1.00 | Dongbei | 0.66 | Xiang | 0.64 |

| Harbin | Yue | 1.74 | Chuan | 1.19 | Islamic | 0.93 | Dongbei ** | 0.88 | Zhe | 0.58 |

| Hefei | Chuan | 1.38 | Hui ** | 0.96 | Yue | 0.77 | Zhe | 0.72 | Xiang | 0.56 |

| Hohhot | Chuan | 1.35 | Xibei | 0.96 | Islamic | 0.74 | Zhe | 0.61 | Dongbei | 0.59 |

| Jinan | Chuan | 1.26 | Lu ** | 1.04 | Jing | 0.87 | Islamic | 0.72 | Dongbei | 0.42 |

| Kunming | Chuan | 1.28 | Yue | 1.12 | Yungui ** | 0.83 | Islamic | 0.66 | Dongbei | 0.47 |

| Lanzhou | Chuan | 1.30 | Xiang | 0.95 | Islamic | 0.77 | Xibei ** | 0.65 | Dongbei | 0.52 |

| Lhasa | Chuan | 1.16 | Xiang | 1.14 | Islamic | 0.69 | Zhe | 0.59 | Dongbei | 0.54 |

| Nanchang | Chuan | 1.40 | Gan ** | 0.99 | Yue | 0.96 | Xiang | 0.74 | Zhe | 0.31 |

| Nanjing | Yue | 1.39 | Chuan | 1.36 | Su ** | 1.01 | Dongbei | 0.61 | Zhe | 0.44 |

| Nanning | Yue | 1.21 | Chuan | 1.07 | Xiang | 1.03 | Dongbei | 0.80 | Zhe | 0.66 |

| Shanghai | Yue | 1.76 | Chuan | 1.37 | Su | 1.34 | Xiang | 0.79 | Zhe | 0.67 |

| Shenyang | Yue | 1.68 | Zhe | 1.30 | Chuan | 1.28 | Dongbei ** | 0.84 | Islamic | 0.66 |

| Shijiazhuang | Chuan | 1.36 | Islamic | 0.88 | Ji ** | 0.75 | Dongbei | 0.75 | Zhe | 0.41 |

| Taiyuan | Chuan | 1.41 | Xiang | 1.05 | Shanxi ** | 0.74 | Dongbei | 0.60 | Zhe | 0.47 |

| Tianjin | Chuan | 1.39 | Islamic | 1.17 | Xiang | 0.98 | Jin ** | 0.88 | Dongbei | 0.67 |

| Urumqi | Chuan | 1.28 | Zhe | 1.16 | Yue | 1.04 | Xiang | 0.91 | Islamic ** | 0.75 |

| Wuhan | Chuan | 1.30 | Yue | 1.13 | Chu ** | 0.94 | Xiang | 0.67 | Zhe | 0.59 |

| Xi’an | Chuan | 1.21 | Xibei ** | 1.09 | Shanxi | 1.04 | Islamic | 0.94 | Xiang | 0.53 |

| Xining | Zhe | 1.56 | Chuan | 1.34 | Xibei ** | 0.99 | Xiang | 0.98 | Islamic | 0.73 |

| Yinchuan | Chuan | 1.41 | Xibei ** | 0.83 | Islamic | 0.72 | Xiang | 0.64 | Dongbei | 0.42 |

| Zhengzhou | Yue | 1.42 | Chuan | 1.33 | Islamic | 1.03 | Xiang | 0.85 | Yu ** | 0.79 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, J.; Xu, Y.; Fang, Z.; Shaw, S.-L.; Liu, X. Geographic Prevalence and Mix of Regional Cuisines in Chinese Cities. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2018, 7, 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi7050183

Zhu J, Xu Y, Fang Z, Shaw S-L, Liu X. Geographic Prevalence and Mix of Regional Cuisines in Chinese Cities. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2018; 7(5):183. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi7050183

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Jingwei, Yang Xu, Zhixiang Fang, Shih-Lung Shaw, and Xingjian Liu. 2018. "Geographic Prevalence and Mix of Regional Cuisines in Chinese Cities" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 7, no. 5: 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi7050183