Positive Response to Thermobalancing Therapy Enabled by Therapeutic Device in Men with Non-Malignant Prostate Diseases: BPH and Chronic Prostatitis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Evaluation

2.3. Participants and Interventions

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

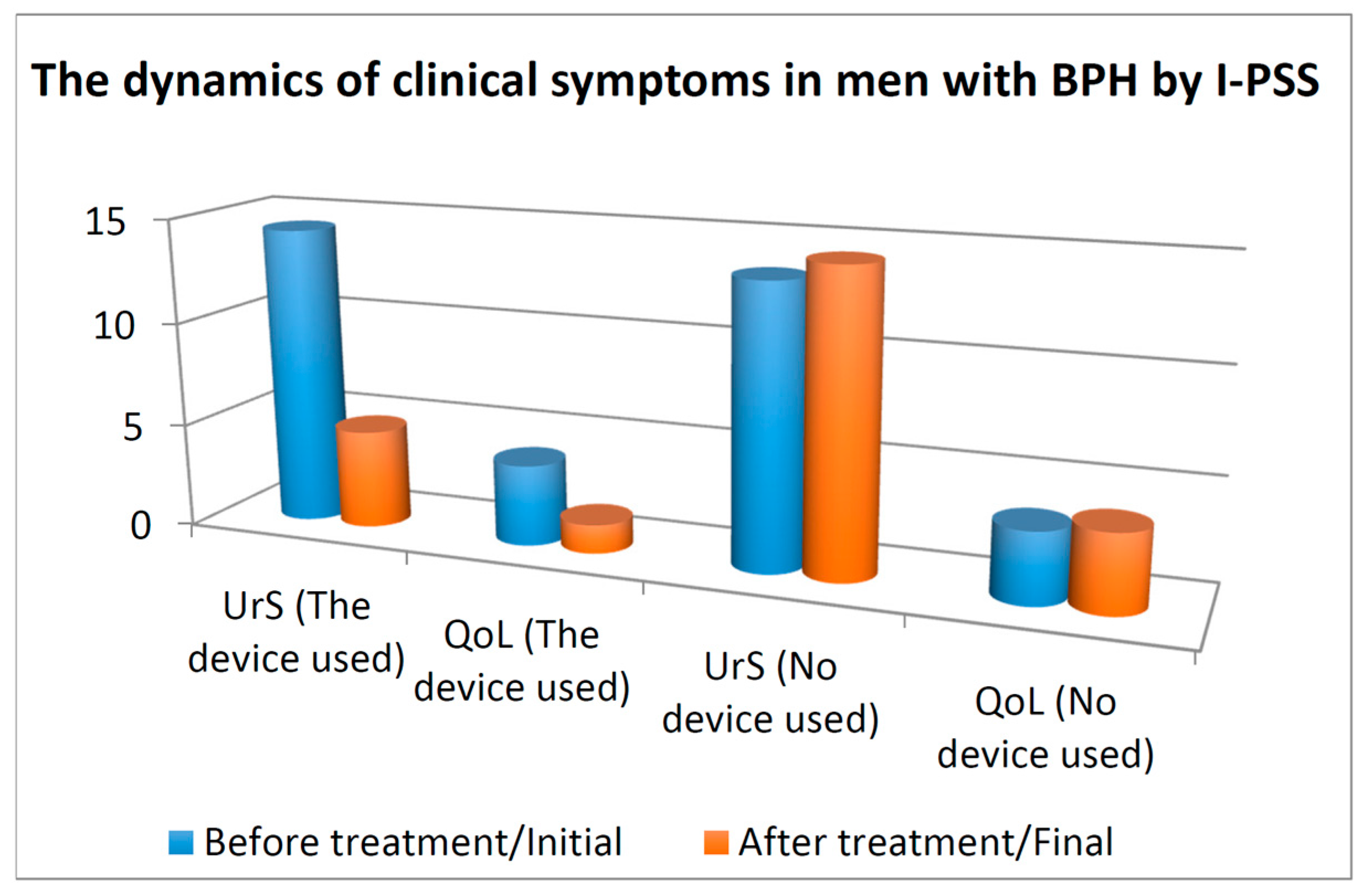

3.1. Urinary Symptoms and QoL

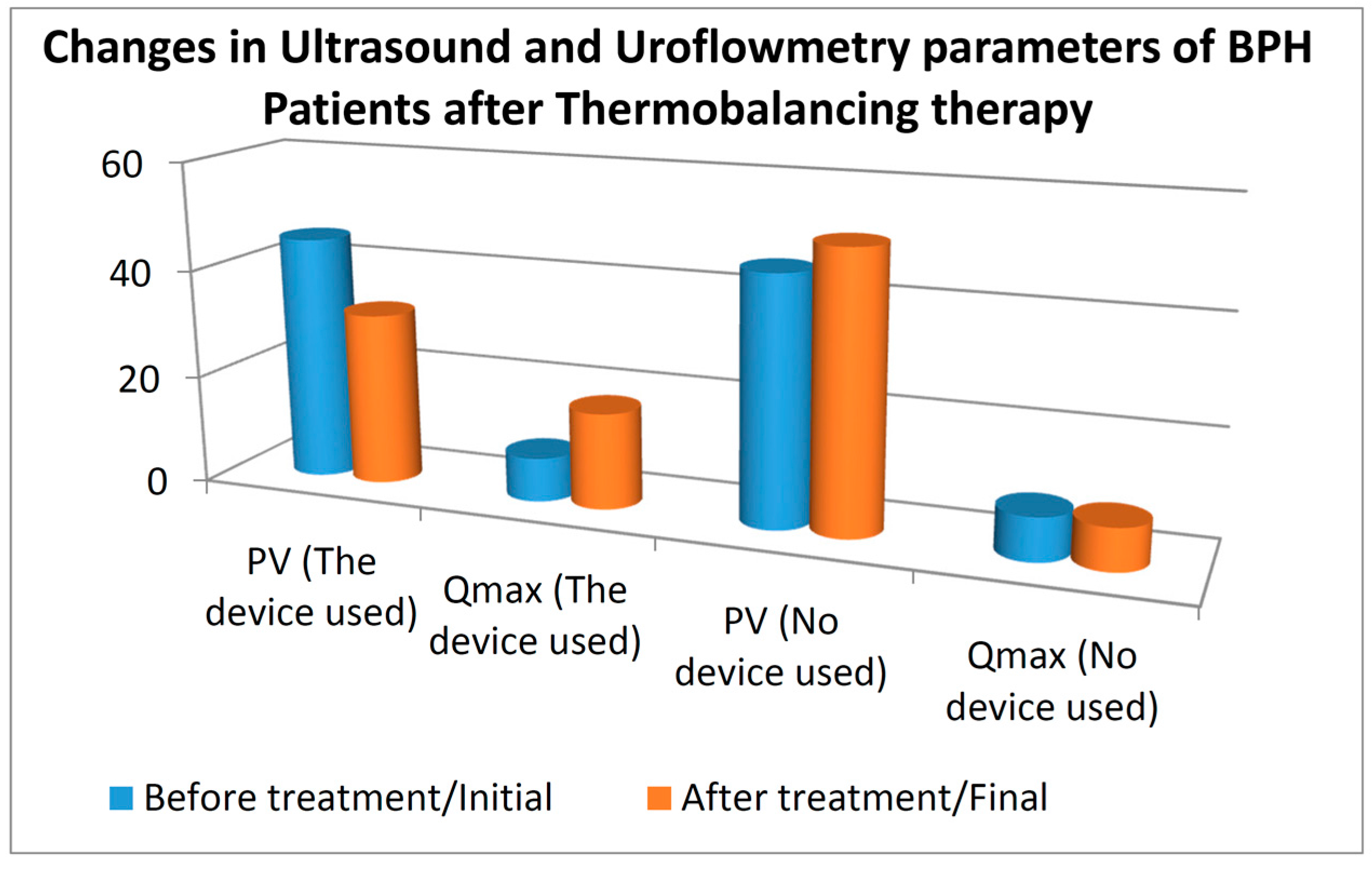

3.2. Prostate Volume and Qmax

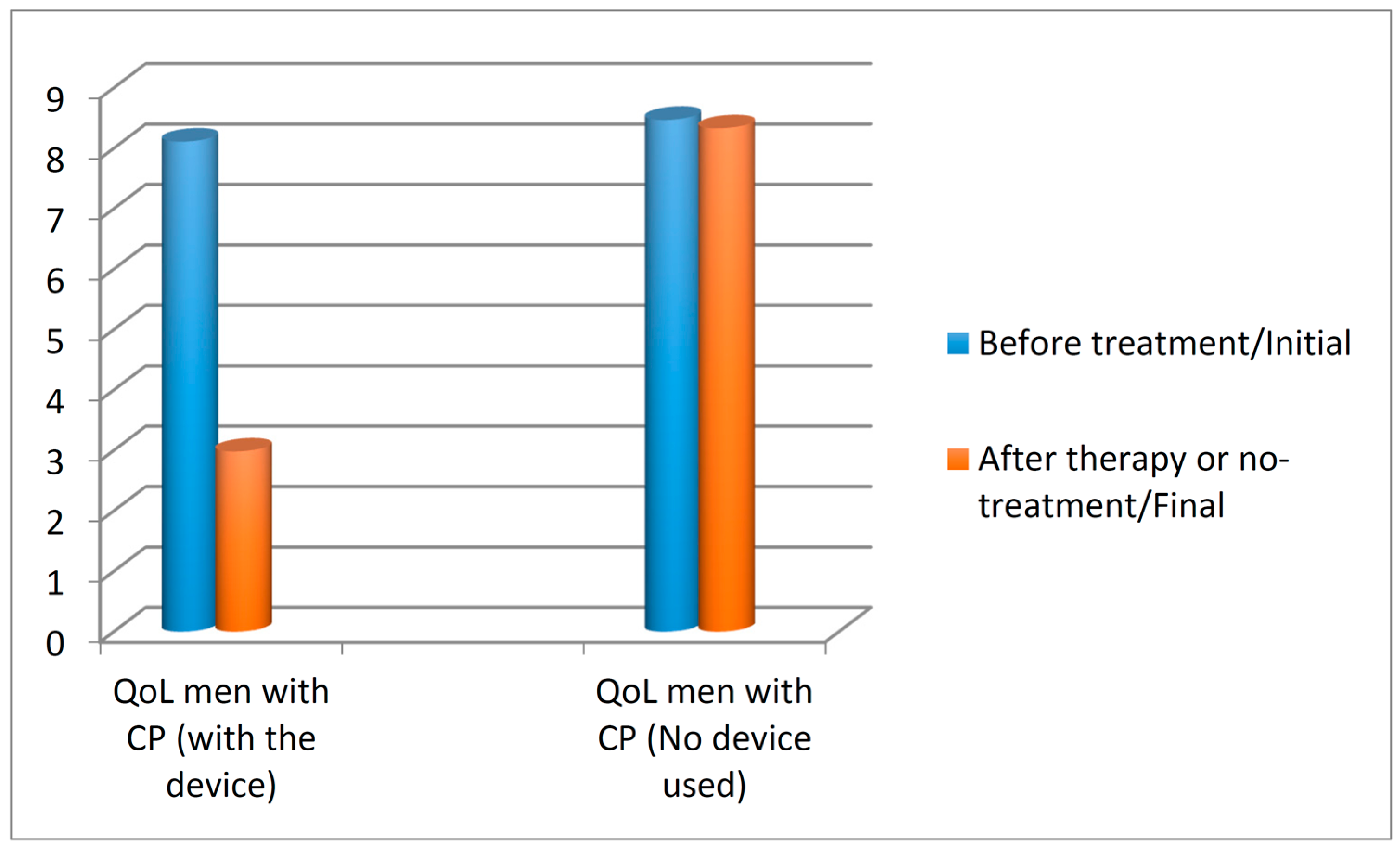

3.3. Quality of Life Score in Patients with Chronic Prostatitis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Epidemiology and Pathogenesis of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. Available online: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-and-pathogenesis-of-benign-prostatic-hyperplasia (accessed on 11 August 2015).

- Magistro, G.; Wagenlehner, F.M.; Grabe, M.; Weidner, W.; Stief, C.G.; Nickel, J.C. Contemporary management of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Eur. Urol. 2016, 69, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, W.L. Benign prostate hyperplasia with chronic prostatitis: An update. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue 2010, 16, 646–650. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shoskes, D.A.; Prots, D.; Karns, J.; Horhn, J.; Shoskes, A.C. Greater endothelial dysfunction and arterial stiffness in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome—A possible link to cardiovascular disease. J. Urol. 2011, 186, 907–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chughtai, B.; Lee, D.; Te, A.; Kaplan, S. Role of inflammation in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Rev. Urol. 2011, 13, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bostanci, Y.; Kazzazi, A.; Momtahen, S.; Laze, J.; Djavan, B. Correlation between benign prostatic hyperplasia and inflammation. Curr. Opin. Urol. 2013, 23, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevermer, J.J.; Easley, S.K. Treatment of prostatitis. Am. Fam. Physician 2000, 61, 3015–3022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ficarra, V.; Rossanese, M.; Zazzara, M.; Giannarini, G.; Abbinante, M.; Bartoletti, R.; Mirone, V.; Scaglione, F. The role of inflammation in lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) due to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and its potential impact on medical therapy. Curr. Urol. Rep. 2014, 15, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishiguro, H.; Kawahara, T. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and prostatic diseases. BioMed Res. Int. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahokehr, A.; Vather, R.; Nixon, A.; Hill, A.G. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for lower urinary tract symptoms in benign prostatic hyperplasia: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BJU Int. 2013, 111, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulla, A.; Adams, N.; Bone, M.; Elliott, A.M.; Gaffin, J.; Jones, D.; Knaggs, R.; Martin, D.; Sampson, L.; Schofield, P. Guidance on the management of pain in older people. Age Ageing 2013, 42, i1–i57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, S.; Adjani, A. Therapeutic Device and Method. US 20110152986 A1, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, S.; Aghajanyan, I.G. Benign prostatic hyperplasia treatment with new physiotherapeutic device. Urol. J. 2015, 12, 2371–2376. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chung, S.D.; Lin, H.C. Association between chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome and anxiety disorder: A population-based study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e64630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, J.D.; He, H.G.; Chan, S.W.; Wang, W. Health-related quality of life and psychological well-being in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia: An integrative review. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speakman, M.; Kirby, R.; Doyle, S.; Ioannou, C. Burden of male lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH)—Focus on the UK. BJU Int. 2015, 115, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corona, G.; Vignozzi, L.; Rastrelli, G.; Lotti, F.; Cipriani, S.; Maggi, M. Benign prostatic hyperplasia: A new metabolic disease of the aging male and its correlation with sexual dysfunctions. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2014, 2014, 329456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukacs, B.; Cornu, J.N.; Aout, M.; Tessier, N.; Hodée, C.; Haab, F.; Cussenot, O.; Merlière, Y.; Moysan, V.; Vicaut, E. Management of lower urinary tract symptoms related to benign prostatic hyperplasia in real-life practice in France: A comprehensive population study. Eur. Urol. 2013, 64, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, S.; Tsounapi, P.; Shimizu, T.; Honda, M.; Inoue, K.; Dimitriadis, F.; Saito, M. Lower urinary tract symptoms, benign prostatic hyperplasia/benign prostatic enlargement and erectile dysfunction: Are these conditions related to vascular dysfunction? Int. J. Urol. 2014, 21, 856–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, K.; Nomiya, M.; Yamaguchi, O. Chronic pelvic ischemia: Contribution to the pathogenesis of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS): A new target for pharmacological treatment? LUTS 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, P.G. Abdominal obesity and intra-abdominal pressure: A new paradigm for the pathogenesis of the hypogonadal-obesity-BPH-LUTS connection. Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Investig. 2012, 11, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Füllhase, C.; Hakenberg, O. New concepts for the treatment of male lower urinary tract symptoms. Curr. Opin. Urol. 2015, 25, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jack, A.S. Inflammation in the pathophysiology of benign prostatic hypertrophy. Eur. Urol. Suppl. 2015, 14, 1455–1458. [Google Scholar]

- Sostres, C.; Gargallo, C.J.; Lanas, A. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and upper and lower gastrointestinal mucosal damage. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2013, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGettigan, P.; Henry, D. Use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs that elevate cardiovascular risk: An examination of sales and essential medicines lists in low-, middle-, and high-income countries. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aghajanyan, I.G.; Allen, S. Positive Response to Thermobalancing Therapy Enabled by Therapeutic Device in Men with Non-Malignant Prostate Diseases: BPH and Chronic Prostatitis. Diseases 2016, 4, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases4020018

Aghajanyan IG, Allen S. Positive Response to Thermobalancing Therapy Enabled by Therapeutic Device in Men with Non-Malignant Prostate Diseases: BPH and Chronic Prostatitis. Diseases. 2016; 4(2):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases4020018

Chicago/Turabian StyleAghajanyan, Ivan Gerasimovich, and Simon Allen. 2016. "Positive Response to Thermobalancing Therapy Enabled by Therapeutic Device in Men with Non-Malignant Prostate Diseases: BPH and Chronic Prostatitis" Diseases 4, no. 2: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases4020018