Decoding the XXI Century’s Marketing Shift: An Agency Theory Framework

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background of Agency Theory

3. The Marketing Paradigm Shifts

3.1. Customers as “Agencies”

3.2. The New Concept of Value Creation

3.3. Product as an “Eigenform”

“Isn’t it strange how this castle changes as soon as one imagines that Hamlet lived here? As scientists we believe that a castle consists only of stones, and admire the way the architect put them together. The stones, the green roof with its patina, the wood carvings in the church, constitute the whole castle. None of this should be changed by the fact that Hamlet lived here, and yet it is changed completely. Suddenly the walls and the ramparts speak a different language.[...] Yet all we really know about Hamlet is that his name appears in a thirteenth-century chronicle. [...] But everyone knows the questions Shakespeare had him ask, the human depths he was made to reveal, and so he too had to be found a place on earth, here in Kronberg.”([47], p. 45)

“For an observer there are two primary modes of perception: compresence and coalescence. Compresence connotes the coexistence of separate entities together in one including space. Coalescence connotes the one space holding, in perception, the observer and the observed, inseparable in an unbroken wholeness. Coalescence is the constant condition of our awareness. Coalescence is the world taken in simplicity. Compresence is the world taken in apparent multiplicity.”

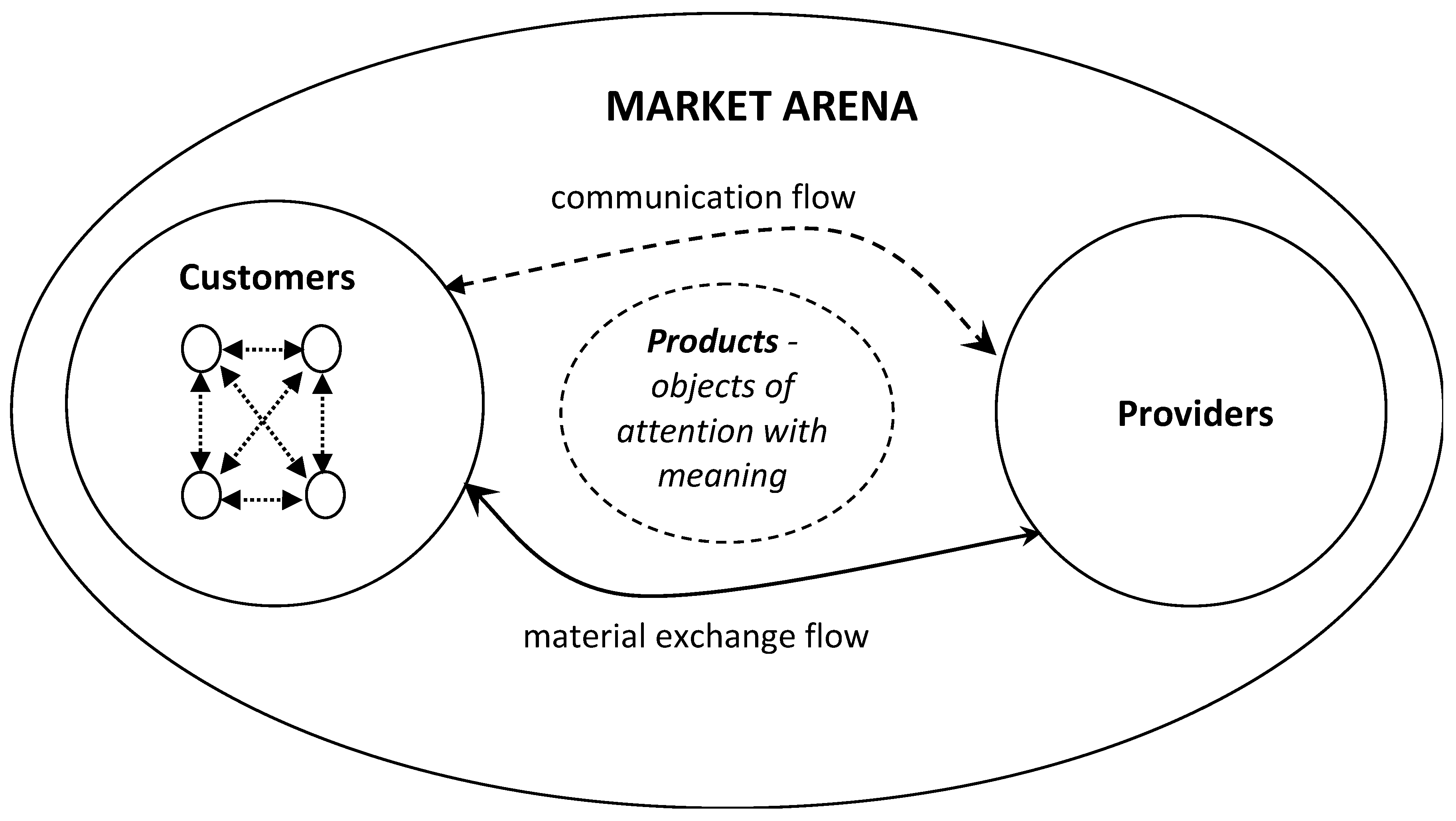

3.4. A New Notion of the Market as an Arena for Agencies

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brown, S. Marketing as Multiplex: Screening Postmodernism. Eur. J. Mark. 1994, 28, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, L.T.; Torp, S.A.; Firat, F. Integrated marketing communication and postmodernity: An odd couple? Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2005, 10, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cova, B.; Cova, V. Tribal marketing: The tribalisation of society and its impact on the conduct of marketing. Eur. J. Mark. 2002, 36, 595–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goneos-Malka, A.; Grobler, A.; Strasheim, A. Suggesting new communication tactics using digital media to optimise postmodern traits in marketing. S. Afr. J. Commun. Theory Res. 2013, 39, 122–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firat, A.F.; Dholakia, N. Theoretical and philosophical implications of postmodern debates some challenges to modern marketing. Mark. Theory 2006, 6, 123–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C. Service logic revisited: Who creates value? And who co-creates? Eur. Bus. Rev. 2008, 20, 298–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C.; Strandvik, T.; Heinonen, K. Value Co-Creation: Critical Reflections. In The Nordic School—Service Marketing and Management for the Future; Gummerus, J., von Koskull, C., Eds.; CERS, Hanken School of Economics: Helsinki, Finland, 2015; pp. 69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Vancouver, J.B. Living systems theory as a paradigm for organizational behavior: Understanding humans, organizations, and social processes. Behav. Sci. 1996, 41, 165–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maturana, H.R.; Varela, F.J. Autopoiesis and Cognition; Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science: Boston, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, E. A Metamodel to interpret the Emergence, Evolution and Functioning of Viable Natural Systems. In Proceedings of the European Meeting on Cybernetics and Systems Research, Vienna, Austria, 5–8 April 1994; Trappl, R., Ed.; World Scientific: Singapore, 1994; pp. 1579–1586. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, E. Towards a Holistic Cybernetics: From Science through Epistemology to Being. Cybern. Hum. Knowing. 1997, 4, 17–50. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, E. Anticipating systems: An application to the possible futures of contemporary society. In Proceedings of the Invited paper at CAYS’2001, Fifth International Conference on Computing Anticipatory Systems, Liege, Belgium, 13–18 August 2001.

- Bacharach, S.B. Organisational Theories: Some criteria for evaluation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 496–515. [Google Scholar]

- Whetten, D.A. What Constitutes a Theoretical Contribution. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Haken, H.; Juval, P. Information and Self organization: A Unifying Approach and Application. Entropy 2016, 197, 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Mingers, J. Self-Producing Systems; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Yolles, M.I. Organizations as Complex Systems: An Introduction to Knowledge Cybernetics; Volume Two of the Series Managing the Complex; Information Age Publishing: Greenwich, CT, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Piaget, J. The Psychology of Intelligence; Harcourt and Brace: New York, NY, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, S. The Heart of Enterprise; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, K.L. Political Culture of Individualism and Collectivism. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yolles, M.I.; Fink, G. A General theory of generic modelling and paradigm shifts: Part 1—The fundamentals. Kybernetes 2010, 44, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolles, M.I.; Fink, G. A General theory of generic modelling and paradigm shifts: Part 2. Cybernetics orders. Kybernetes 2015, 44, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolles, M.I.; Fink, G. A General theory of generic modelling and paradigm shifts: Part 3. The extension. Kybernetes 2015, 44, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.G. Living Systems; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Rampen, W. My Personal Definition of Business with Customer Value Co-Creation, Customer Think. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, S. Symbols for sale. In Harvard Business Review; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1959; Volume 37, pp. 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, S. Dreams, Fairy Tales, Animals and Cars. Psychol. Mark. 1985, 2, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCracken, G. Culture and Consumption: A Theoretical Account of the Structure and Movement of the Cultural Meaning of Consumer Goods. J. Consum. Res. 1986, 13, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniz, A.M. Brand community and the negotiation of brand meaning. In Advances in Consumer Research, Volume 24, ed.; Brucks, M., MacInnis, D.J., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research: Provo, UT, USA, 1997; pp. 308–309. [Google Scholar]

- Broderick, A.; MacLaran, P.; Ma, P.Y. Brand Meaning Negotiation and the Role of the Online Community: A Mini Case Study. J. Custom. Behav. 2003, 2, 75–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominici, G.; Basile, G.; Palumbo, F. Viable systems approach and consumer culture theory: A conceptual framework. J. Organ. Transform. Soc. Change 2013, 10, 262–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espejo, R.; Dominici, G. Cybernetics of Value Cocreation for Product Development. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2016, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toffler, A. The Third Wave; Bantam: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Packard, V. The Hidden Persuaders; David McKay Company: New York, NY, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Hackley, C.; Tiwsakul, R.A.; Preuss, L. An ethical evaluation of product placement: A deceptive practice? Bus. Eth. Eur. Rev. 2008, 17, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normann, R.; Ramirez, R. Designing Interactive Strategy. Harvard Business Review. 1993. Available online: https://hbr.org/1993/07/designing-interactive-strategy (accessed on 8 January 2016).

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Service-dominant logic: Continuing the evolution. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusch, R.F.; Vargo, S.L. Service Dominant Logic: Premises, Perspectives, Possibilities; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Grönroos, C. Adopting a service logic for marketing. Mark. Theory 2006, 6, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, R.B.; Flint, D.J. Marketing’s service dominant logic and customer value. In The Service-Dominant Logic of Marketing: Dialog, Debate and Direction; Lusch, R.F., Vargo, S.L., Eds.; M.E. Sharpe: Armonk, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 183–195. [Google Scholar]

- Kalaignanam, K.; Varadarajan, R. Customers as coproducers: Implications for marketing strategy effectiveness and marketing operations efficiency. In The Service Dominant Logic of Marketing: Dialog, Debate and Direction; Lusch, R.F., Vargo, S.L., Eds.; M.E. Sharpe: Armonk, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 166–179. [Google Scholar]

- Etgar, M. A descriptive model of the consumer co-production process. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.T.; Armstrong, G. Principles of Marketing: Global Edition; Pearson Education: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman, L.H. Eigenform. In Proceedings of the 51st Annual Meeting of the ISSS—2007, Tokyo, Japan, 5–10 August 2007; Available online: www.isss.org/index.php/proceedings51st/article/view/811/295 (accessed on 7 Janaury 2016).

- Bruner, J. Actual Minds, Possible Worlds; Harvard University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Cusumano, M.A.; Mylonadis, Y.; Rosenbloom, R.S. Strategic Maneuvering and Mass-Market Dynamics: The Triumph of VHS over Beta. Bus. Hist. Rev. 1992, 66, 51–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schembri, S. Reframing brand experience: The experiential meaning of Harley–Davidson. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 1299–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, J. Why Harley-Davidson May Not Be the Perfect Ride for Scott Walker. 2015. Available online: http://www.bloomberg.com/politics/articles/2015-08-13/harley-davidson-may-not-be-the-perfect-ride-for-scott-walker (accessed on 12 April 2016).

- Schouten, J.W.; McAlexander, J.H. Subcultures of Consumption: An Ethnography of the New Bikers. J. Consum. Res. 1995, 22, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. Powerful Symmetries and Eigenforms. 2011. Available online: http://dailyimprovisation.blogspot.co.uk/2011/11/powerful-symmetries-and-eigenforms.html (accessed on 11 April 2016).

- Von Foerster, H. Observing Systems; The Systems Inquiry Series; Intersystems Publications: Salina, CA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman, L.H. Eigenform. Kybernetes 2005, 34, 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Cybernetics’sreflexive turns. Cybern. Hum. Knowing 2008, 15, 173–184. [Google Scholar]

- Achterbergh, J.; Vriens, D. Organizations. In Social Systems Conducting Experiments, 2nd ed.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Varela, F.J.; Thompson, E.; Rosch, E. The Embodied Mind; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. Reassembling the social. In An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lebra, T.S. Japanese Patterns of Behaviour; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- De Vries, M.F.R. The entrepreneurial personality: A person at the crossroads. J. Manag. Stud. 1977, 14, 34–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilsky, W.; Schwartz, S.H. Values and personality. Eur. J. Personal. 1994, 8, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez, J. Personality and health-protective behaviour. Eur. J. Personal. 1999, 13, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolles, M.I.; Fink, G. Personality, pathology and mindsets: Part 1—Agency, personality and mindscapes. Kybernetes 2014, 43, 92–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolles, M.I.; Fink, G. Personality, pathology and mindsets: Part 2—Cultural traits and enantiomers. Kybernetes 2014, 43, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolles, M.I.; Fink, G. Personality, pathology and mindsets: Part 3—Pathologies and corruption. Kybernetes 2014, 43, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, A.; Penaloza, L.; Firat, A.F. The Market as a Sign System and the Logic of the Market. In The Service-Dominant Logic of Marketing: Dialog, Debate and Directions; Lusch, R.F., Vargo, S.L., Eds.; M.E. Sharpe: Armonk, NY, USA; London, UK, 2006; pp. 251–265. [Google Scholar]

- Eagle, N.; Pentland, A.S. Eigenbehaviors: Identifying structure in routine. In Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; Volume 63, pp. 1057–1066. [Google Scholar]

- Thietart, R.A.; Forgues, B. Chaos theory and organization. Organ. Sci. 1995, 6, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plowman, D.A.; Baker, L.T.; Beck, T.E.; Kulkarni, M.; Solansky, S.T.; Travis, D.V. Radical change accidentally: The emergence and amplification of small change. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 515–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolles, M.; Fink, G. The changing organisation: An agency modelling approach. Int. J. Mark. Bus. Syst. 2015, 1, 217–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.; Deragon, J.T.; Orem, M.G.; Smith, C.F. The Knowledge Factors. The Emergence of the Relationship Economy: The New Order of Things to Come. Link to your worls LLC, Cupertino, CA, USA, 2008. Available online: http://theengagingbrand.typepad.com/the_engaging_brand_/files/RelationshipEconomy-eBookv.04.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2016).

- Charron, C.; Favier, J.; Li, C. Social Computing: How Networks Erode Institutional Power, and What to Do about It; Forrester Customer Report. Forrester Research Inc., 2006. Available online: http://www.cisco.com/web/offer/socialcomputing/SocialComputingBigIdea.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2016).

- Boje, D.M. Narrative Methods for Organisational and Communication Research; Sage: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pongsakornrungsilp, S.; Schroeder, J.E. Understanding value co-creation in a co-consuming brand community. Mark. Theory 2011, 11, 303–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B. Consumption experience, customer value, and subjective personal introspection: An illustrative photographic essay. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermas, J. The Theory of Communicative Action. In Reason and the Rationalization of Society; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. The Theory of Communicative Action. In Lifeworld and System: A Critique of Functionalist Reason; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, A.; Luckmann, T. The Structures of the Lifeworld; Heinamann: London, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dominici, G.; Yolles, M. Decoding the XXI Century’s Marketing Shift: An Agency Theory Framework. Systems 2016, 4, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems4040035

Dominici G, Yolles M. Decoding the XXI Century’s Marketing Shift: An Agency Theory Framework. Systems. 2016; 4(4):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems4040035

Chicago/Turabian StyleDominici, Gandolfo, and Maurice Yolles. 2016. "Decoding the XXI Century’s Marketing Shift: An Agency Theory Framework" Systems 4, no. 4: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems4040035