One-Step Potentiostatic Deposition of Micro-Particles on Al Alloy as Superhydrophobic Surface for Enhanced Corrosion Resistance by Reducing Interfacial Interactions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation

2.3. Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fabrication of Superhydrophobic Surfaces

3.2. Anticorrosion Behaviors of as-Prepared Al Alloys

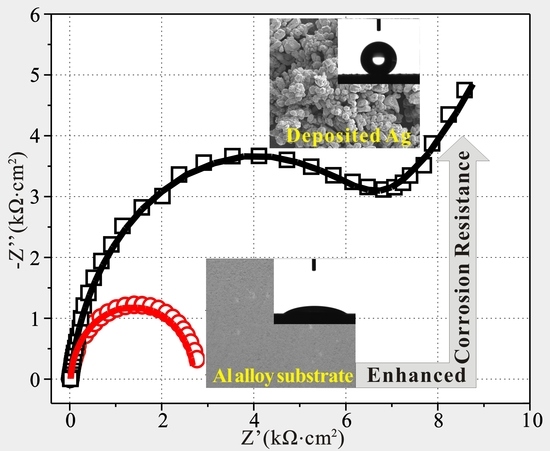

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, T.; Luo, H.Y.; Su, Y.Q.; Xu, P.W.; Luo, J.; Li, S.J. Effect of precipitate embryo induced by strain on natural aging and corrosion behavior of 2024 Al alloy. Coatings 2018, 8, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massardier, V.; Epicier, T.; Merle, P. Correlation between the microstructural evolution of a 6061 aluminium alloy and the evolution of its thermoelectric power. Acta Mater. 2017, 48, 2911–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, I.K.; Cho, S.H.; Kim, S.J.; Jo, Y.S.; Kim, S.H. Improved corrosion resistance of 5xxx aluminum alloy by homogenization heat treatment. Coatings 2018, 8, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katkar, V.A.; Gunasekaran, G. Galvanic corrosion of AA6061 with other ship building materials in seawater. Corrosion 2015, 72, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.D.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Z.Y.; Yang, C.H.; Ding, G.Q.; Li, X.G. Galvanic series of metals and effect of alloy compositions on corrosion resistance in Sanya seawater. Acta Metall. Sin. 2018, 54, 1311–1321. [Google Scholar]

- Jedrusik, M.; Debowska, A.; Kopia, A. Characterisationof oxide coatings produced on aluminum alloys by MAO and chemical methods. Arch. Metall. Mater. 2018, 63, 125–128. [Google Scholar]

- Kwolek, P.; Krupa, K.; Obloj, A.; Kocurek, P.; Wierzbinska, M.; Sieniawski, J. Tribological properties of the oxide coatings produced onto 6061-T6 aluminum alloy in the hard anodizing process. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2018, 27, 3268–3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Huang, J.M.; Claypool, J.B.; Castano, C.E.; O’Keefe, M.J. Structure and corrosion behavior of sputter deposited cerium oxide based coatings with various thickness on Al 2024-T3 alloy substrates. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 355, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serizawa, A.; Oda, T.; Watanabe, K.; Mori, K.; Yokomizo, T.; Ishizaki, T. Formation of anticorrosive film for suppressing pitting corrosion on Al-Mg-Si alloy by steam coating. Coatings 2018, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Battocchi, D.; Bierwagen, G.P. Inhibitors for prolonging corrosion protection of Mg-rich primer on al alloy 2024-T3. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2017, 14, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikku, G.S.; Jeyasubramanian, K.; Venugopal, A.; Ghosh, R. Corrosion resistance behaviour of graphene/polyvinyl alcohol nanocomposite coating for aluminium-2219 alloy. J. Alloy. Compd. 2017, 716, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Ji, Q.Q.; Jin, M. Effects of non-isothermal aging process on mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of Al-Mg-Si aluminum alloy. Mater. Corros. 2018, 69, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.C.; Jiang, Y.Q.; Xia, Y.C.; Zhang, X.C.; Zhou, H.M.; Deng, J. Effects of creep-aging processing on the corrosion resistance and mechanical properties of an Al-Cu-Mg alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2014, 605, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seikh, A.H.; Baig, M.; Ammar, H.R.; Alam, M.A. The influence of transition metals addition on the corrosion resistance of nanocrystalline Al alloys produced by mechanical alloying. Metals 2016, 6, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravnikar, D.; Rajamure, R.S.; Trdan, U.; Dahotre, N.B.; Grum, J. Electrochemical and DFT studies of laser-alloyed TiB2/TiC/Al coatings on aluminium alloy. Corros. Sci. 2018, 136, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.X.; Gu, X.H.; Qin, P.; Dai, N.W.; Li, X.P.; Kruth, J.P.; Zhang, L.C. Improved corrosion behavior of ultrafine-grained eutectic Al-12Si alloy produced by selective laser melting. Mater. Des. 2018, 146, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaseem, M.; Yong, H.L.; Ko, Y.G. Incorporation of MoO2, and ZrO2, particles into the oxide film formed on 7075 Al alloy via micro-arc oxidation. Mater. Lett. 2016, 182, 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.P.; Weng, Y.C.; Wu, Z.Z.; Ma, Z.Y.; Tian, X.B.; Fu, R.K.Y.; Lin, H.; Wu, G.S.; Chu, P.K.; Pan, F. Excellent corrosion resistance of P and Fe modified micro-arc oxidation coating on Al alloy. J. Alloy. Compd. 2017, 710, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navaser, M.; Atapour, M. Effect of friction stir processing on pitting corrosion and intergranular attack of 7075 aluminum alloy. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2017, 2, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Li, W.Y.; Xu, Y.X.; Yang, X.W.; Alexopoulos, N.D. Influence of rotation speed on mechanical properties and corrosion sensitivity of friction stir welded AA2024-T3 joints. Mater. Corros. 2018, 69, 1016–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, D.; Yao, C.W.; Lian, I. Mechanical durability of engineered superhydrophobic surfaces for anti-corrosion. Coatings 2018, 8, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.W.; Zhang, Q.X.; Guo, Z.; Shi, T.; Yu, J.G.; Tang, M.K.; Huang, X.J. Fabrication of superhydrophobic surface with improved corrosion inhibition on 6061 aluminum alloy substrate. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 342, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, I.S. On the durability and wear resistance of transparent superhydrophobic coatings. Coatings 2017, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.Y.; Liu, S.; Wei, S.F.; Liu, Y.; Lian, J.S.; Jiang, Q. Robust superhydrophobic surface on Al substrate with durability, corrosion resistance and ice-phobicity. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, X.W.; Liu, C.; Shi, T.; Lei, Y.J.; Zhang, Q.X.; Zhou, C.; Huang, X.J. Preparation of multifunctional Al alloys substrates based on micro/nanostructures and surface modification. Mater. Des. 2017, 122, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Hwang, W. Exploiting the silicon content of aluminum alloys to create a superhydrophobic surface using the sol-gel process. Mater. Lett. 2016, 168, 83–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizaki, T.; Kumagai, S.; Tsunakawa, M.; Furukawa, T.; Nakamura, K. Ultrafast fabrication of superhydrophobic surfaces on engineering light metals by single-step immersion process. Mater. Lett. 2017, 193, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.H.; Li, Y.D.; Yu, M.; Li, S.M.; Xue, B. A facile approach to superhydrophobic LiAl-layered double hydroxide film on Al-Li alloy substrate. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2015, 12, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.J.; Huang, T.; Lei, J.L.; He, J.X.; Qu, L.F.; Huang, P.L.; Zhou, W.; Li, N.B.; Pan, F.S. Robust biomimetic-structural superhydrophobic surface on aluminum alloy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 7, 1449–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.H.; Jim, B.Y.; Wang, B.; Fu, Y.C.; Zhan, X.L.; Chen, F.Q. Fabrication of a highly stable superhydrophobic surface with dual-scale structure and its antifrosting properties. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 2754–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsanti, L.; Ogihara, H.; Mahanty, S.; Luciano, G. Electrochemical behaviour of superhydrophobic coating fabricated by spraying a carbon nanotube suspension. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2015, 38, 579–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.K.; Huang, X.J.; Guo, Z.; Yu, J.G.; Li, X.W.; Zhang, Q.X. Fabrication of robust and stable superhydrophobic surface by a convenient, low-cost and efficient laser marking approach. Colloids Surf. A 2015, 484, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.P.; Chen, X.H.; Yang, G.B.; Yu, L.G.; Zhang, P.Y. Fabrication and characterization of stable superhydrophobic surface with good friction-reducing performance on Al foil. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 300, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Y.; Dale, B.; Akisik, F.; Koons, K.; Lin, C. Preparation and anti-icing behavior of superhydrophobic surfaces on aluminum alloy substrates. Langmuir 2013, 29, 8482–8491. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.Y.; Lu, S.X.; Xu, W.G.; He, G.; Yu, T.L.; Cheng, Y.Y.; Wu, B. Fabrication of stable Ni-Al4Ni3-Al2O3superhydrophobic surface on aluminum substrate for self-cleaning, anti-corrosive and catalytic performance. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 1097–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J.; Hu, W.; Xue, M.; Wang, F.; Li, W. One-step solution immersion process to fabricate superhydrophobic surfaces on light alloys. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 9867–9871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleema, N.; Sarkar, D.K.; Gallant, D.; Paynter, R.W.; Chen, X.G. Chemical nature of superhydrophobic aluminum alloy surfaces produced via a one-step process using fluoroalkyl-silane in a base medium. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 3, 4775–4781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.W.; Li, S.; Cheng, Z.L.; Xu, G.Y.; Quan, X.J.; Zhou, Y.T. Facile fabrication of super-hydrophobic FAS modified electroless Ni-P coating meshes for rapid water-oil separation. Colloids Surf. A 2018, 540, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Nam, Y.; Lastakowski, H.; Hur, J.I.; Shin, S.; Biance, A.L.; Pirat, C.; Kim, C.J.; Ybert, C. Two types of cassie-to-wenzel wetting transitions on superhydrophobic surfaces during drop impact. Soft Matter 2015, 11, 4592–4599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Chen, H. Preparation and anti-icing property of a porous superhydrophobic magnesium oxide coating with low sliding angle. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 557–559, 1884–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Kong, J.Y.; Wang, X.D.; Li, X.W. Preparation of multifunctional Al-Mg alloy surface with hierarchical micro/nanostructures by selective chemical etching processes. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 389, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.W.; Shi, T.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Q.X.; Huang, X.J. Multifunctional substrate of Al alloy based on general hierarchical micro/nanostructures: Superamphiphobicityand enhanced corrosion resistance. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, R.; Li, W.; Wang, B.; Luo, Q.; Ma, F.M.; Yu, Z.L. Optimal conditions for the preparation of superhydrophobic surfaces on Al substrates using a simple etching approach. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012, 258, 7031–7035. [Google Scholar]

| Element | Mg | Fe | Mn | Zn | Cu | Si | Cr | Al |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt.% | 1.5 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 97.0 |

| Samples | Rs (Ω·cm2) | Rct (Ω·cm2) | Rc (Ω·cm2) | Rt (Ω·cm2) | W (Ω·cm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate | 12 | 2690 | – | 2690 | – |

| D-sample | 9 | 2416 | – | 2416 | – |

| M-D-sample | 10 | 7105 | 437 | 7542 | 0.0028 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shi, T.; Li, X.; Zhang, Q.; Li, B. One-Step Potentiostatic Deposition of Micro-Particles on Al Alloy as Superhydrophobic Surface for Enhanced Corrosion Resistance by Reducing Interfacial Interactions. Coatings 2018, 8, 392. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings8110392

Shi T, Li X, Zhang Q, Li B. One-Step Potentiostatic Deposition of Micro-Particles on Al Alloy as Superhydrophobic Surface for Enhanced Corrosion Resistance by Reducing Interfacial Interactions. Coatings. 2018; 8(11):392. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings8110392

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Tian, Xuewu Li, Qiaoxin Zhang, and Ben Li. 2018. "One-Step Potentiostatic Deposition of Micro-Particles on Al Alloy as Superhydrophobic Surface for Enhanced Corrosion Resistance by Reducing Interfacial Interactions" Coatings 8, no. 11: 392. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings8110392