Synthesis of Ordered Mesoporous CuO/CeO2 Composite Frameworks as Anode Catalysts for Water Oxidation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Synthesis of Mesoporous Silica

2.2. Synthesis of Mesoporous CuO/CeO2 Composites

2.3. Physical Characterization

2.4. Photocatalytic OER Reactions

3. Results and Discussion

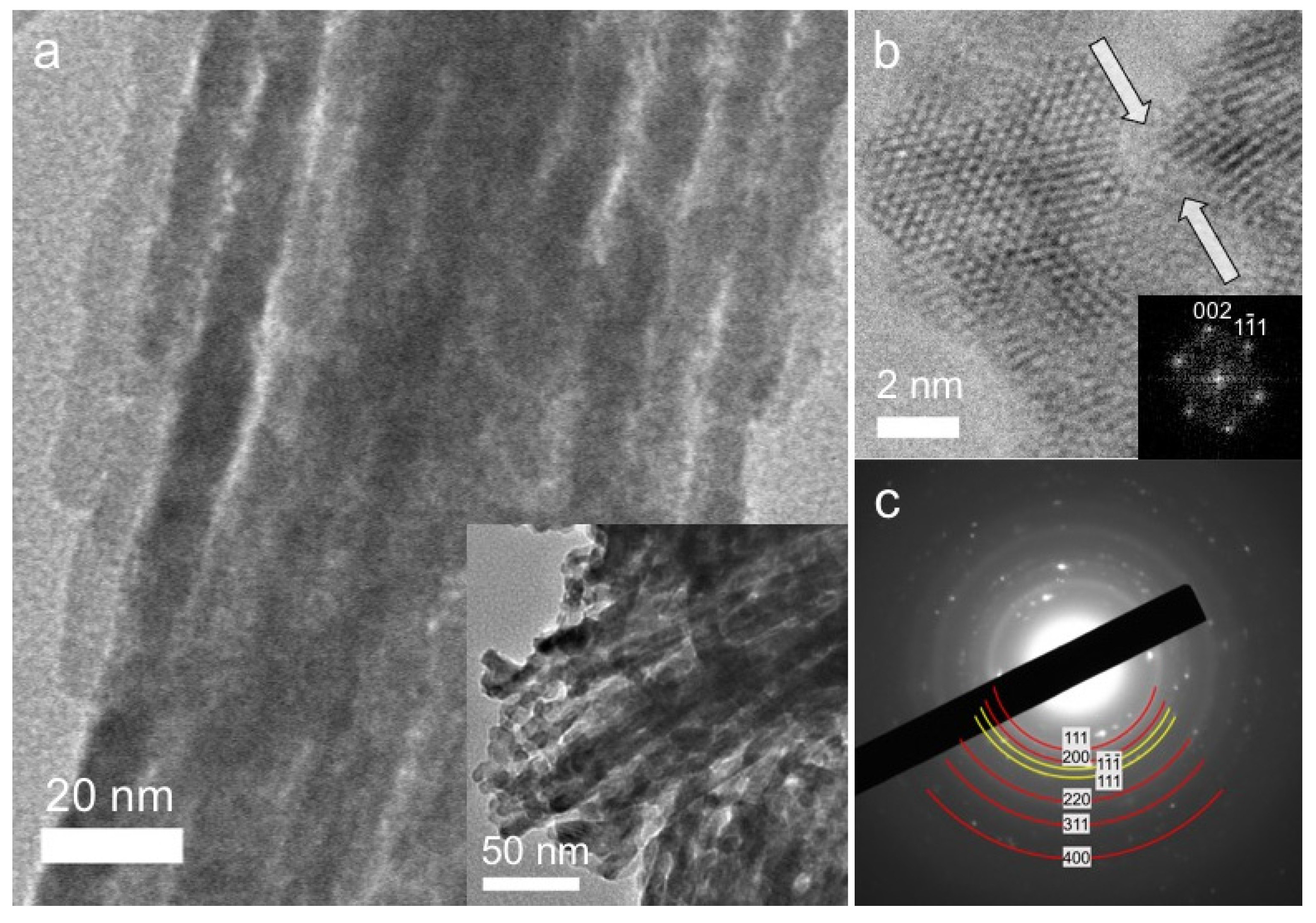

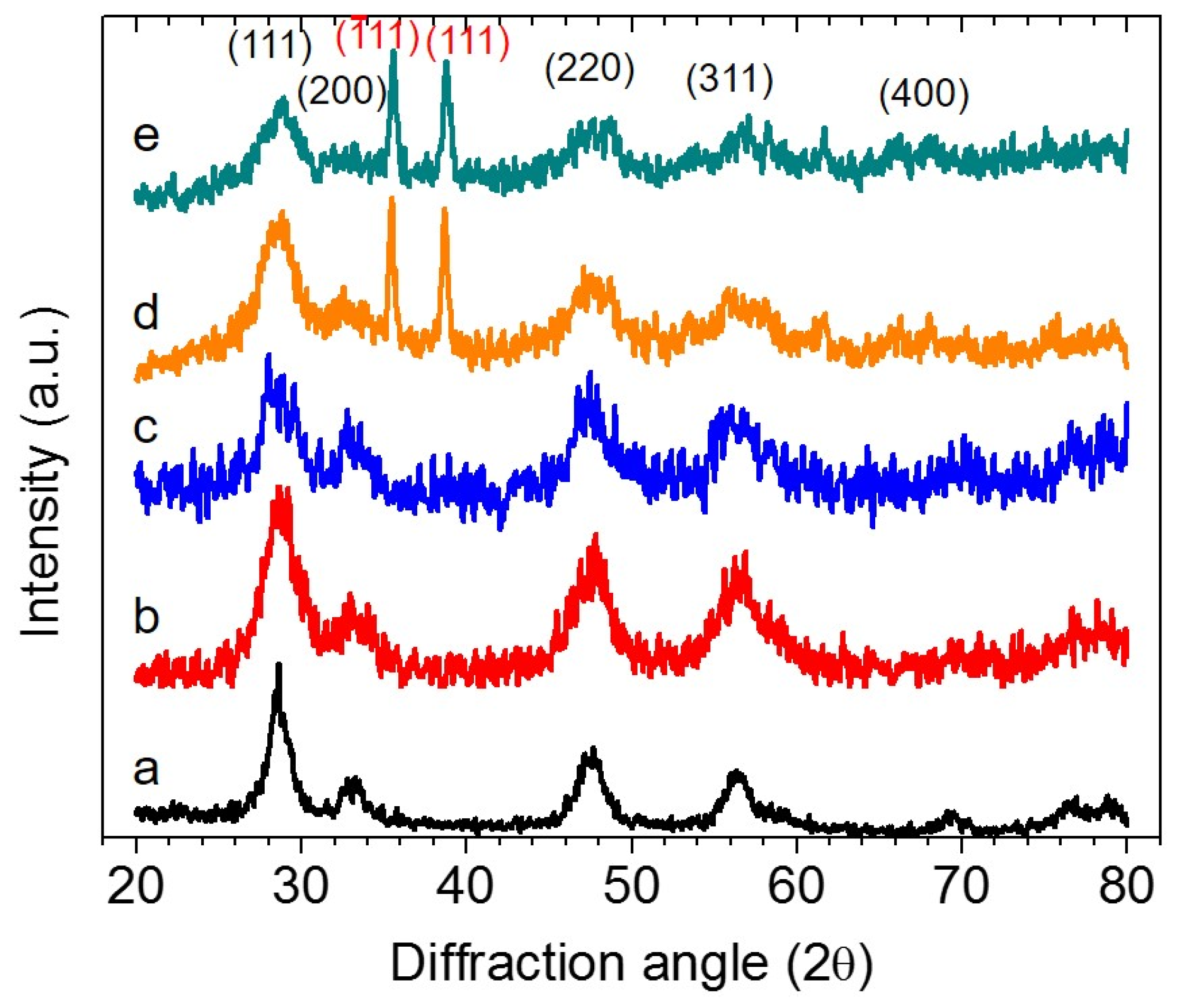

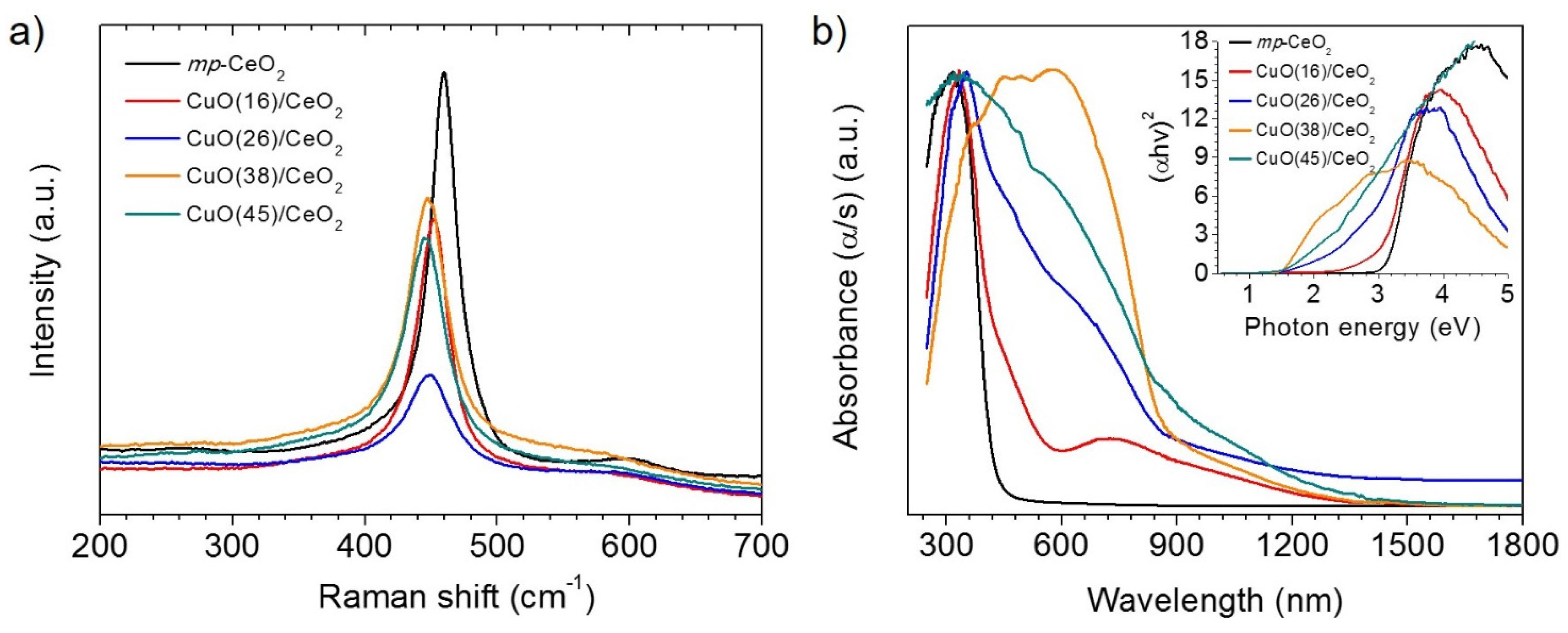

3.1. Morphology and Structural Properties

| Sample | Atomic Ratio a (Ce:Cu) | CuO Loading (wt %) | Surface Area (m2·g−1) | Pore Volume (cm3·g−1) | Pore Size (nm) | Crystal Size b (nm) | Energy Gap (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mp-CeO2 | 142 | 0.21 | 4.1 | 5.7 | 3.14 | ||

| CuO(16)/CeO2 | 71:29 | 16 | 164 | 0.25 | 4.2 | 3.4 | 3.03 |

| CuO(26)/CeO2 | 56:44 | 26 | 150 | 0.24 | 4.6 | 3.2 | 2.83 |

| CuO(38)/CeO2 | 43:57 | 38 | 135 | 0.20 | 4.7 | 3.3 | 1.51 |

| CuO(45)/CeO2 | 36:64 | 45 | 83 | 0.17 | 4.8 | 3.2 | 1.50 |

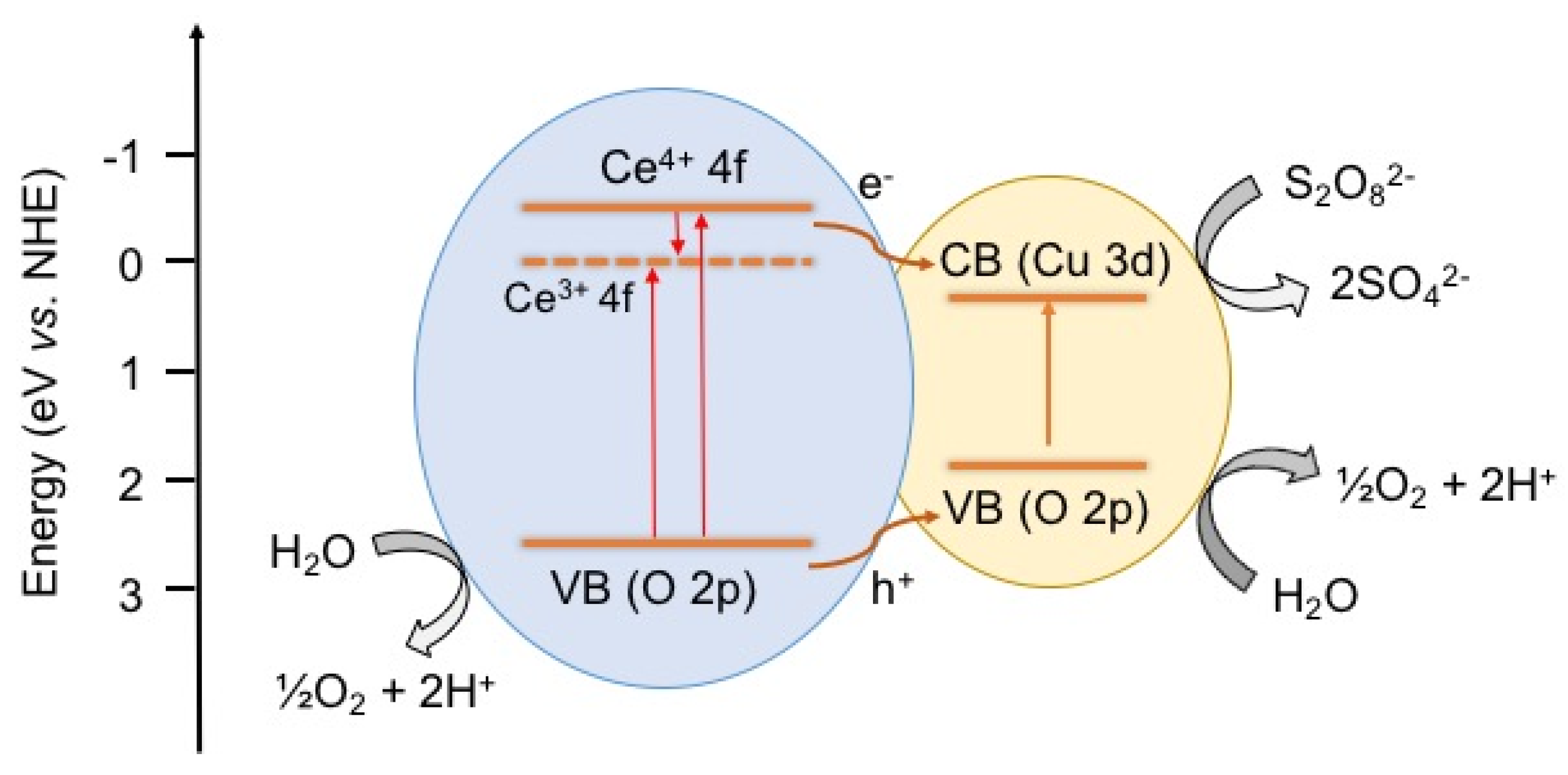

3.2. Photocatalytic OER Reactions

| Catalyst | O2 Evolution Rate (µmol·h−1) | Evolved O2, 5 h (µmol) | TOF a (s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| mp-CeO2 | 1.0 | 5.3 | 1.01 × 10−6 |

| CuO(16)/CeO2 | 16.7 | 109.5 | 1.77 × 10−5 |

| CuO(26)/CeO2 | 18.5 | 120.9 | 1.89 × 10−5 |

| CuO(38)/CeO2 | 19.6 (0.9) b | 134.7 | 2.23 × 10−5 |

| CuO(45)/CeO2 | 13.1 | 95.6 | 1.24 × 10−5 |

| b-CuO(38)/CeO2 | 1.3 | 6.7 | 8.88 × 10−7 |

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Subbaraman, R.; Tripkovic, D.; Chang, K.C.; Strmcnik, D.; Paulikas, A.P.; Hirunsit, P.; Chan, M.; Greeley, J.; Stamenkovic, V.; Markovic, N.M. Trends in activity for the water electrolyser reactions on 3d M(Ni,Co,Fe,Mn) hydr(oxy)oxide catalysts. Nat. Mater. 2012, 11, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, R.; Okamura, T.; Ohashi, N.; Imanishi, A.; Nakato, Y. Molecular Mechanisms of Photoinduced Oxygen Evolution, PL Emission, and Surface Roughening at Atomically Smooth (110) and (100) n-TiO2 (Rutile) Surfaces in Aqueous Acidic Solutions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 12975–12983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J. A review of electrode materials for electrochemical supercapacitors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 797–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadas, I.T.; Christodoulides, J.A.; Kioseoglou, G.; Armatas, G.S. A high surface area ordered mesoporous BiFeO3 semiconductor with efficient water oxidation activity. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 1587–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Ye, J.; Ma, L.; Ouyang, S.; Jing, D.; Guo, L. Site-Selected Doping of Upconversion Luminescent Er3+ into SrTiO3 for Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalytic H2 or O2 Evolution. Chem. Eur. J. 2012, 18, 7543–7551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.W.; Choi, K.-S. Nanoporous BiVO4 Photoanodes with Dual-Layer Oxygen Evolution Catalysts for Solar Water Splitting. Science 2014, 343, 990–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajdich, M.; García-Mota, M.; Vojvodic, A.; Nørskov, J.K.; Bell, A.T. Theoretical Investigation of the Activity of Cobalt Oxides for the Electrochemical Oxidation of Water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 13521–13530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trotochaud, L.; Ranney, J.K.; Williams, K.N.; Boettcher, S.W. Solution-Cast Metal Oxide Thin Film Electrocatalysts for Oxygen Evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 17253–17261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Kuo, C.-H.; Chen, J.; Luo, Z.; Thanneeru, S.; Li, W.; Song, W.; Biswas, S.; Suib, S.L.; He, J. Ligand-Assisted Co-Assembly Approach toward Mesoporous Hybrid Catalysts of Transition-Metal Oxides and Noble Metals: Photochemical Water Splitting. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 9061–9065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muccillo, E.N.S.; Rocha, R.A.; Tadokoro, S.K.; Rey, J.F.Q.; Muccillo, R.; Steil, M.C. Electrical Conductivity of CeO2 Prepared from Nanosized Powders. J. Electroceramics 2004, 13, 609–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchionna, M.; Fornasiero, P. The role of ceria-based nanostructured materials in energy applications. Mater. Today 2014, 17, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serre, C.; Garin, F.; Belot, G.; Marie, G. Reactivity of Pt/Al2O3 and Pt-CeO2Al2O3 Catalysts for the Oxidation of Carbon Monoxide by Oxygen: II. Influence of the Pretreatment Step on the Oxidation Mechanism. J. Catal. 1993, 141, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Dong, X.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, H.; Shi, L. Mesoporous CeO2 and CuO-loaded mesoporous CeO2: Synthesis, characterization, and CO catalytic oxidation property. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater. 2005, 85, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.; Zhu, Y.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, S.; Cheng, F.; Liu, Y.; Wang, P.; Tao, F. Water–Gas Shift Reaction on Metal Nanoclusters Encapsulated in Mesoporous Ceria Studied with Ambient-Pressure X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 9305–9313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, P.; Zhang, J.; Chen, F.; Anpo, M. Ordered Mesoporous CeO2 Synthesized by Nanocasting from Cubic Ia3d Mesoporous MCM-48 Silica: Formation, Characterization and Photocatalytic Activity. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 17809–17813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corma, A.; Atienzar, P.; Garcia, H.; Chane-Ching, J.-Y. Hierarchically mesostructured doped CeO2 with potential for solar-cell use. Nat. Mater. 2004, 3, 394–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yahiro, H.Y.; Baba, K.; Eguchi, H.; Arai, J. High Temperature Fuel Cell with Ceria-Yttria Solid Electrolyte. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1988, 135, 2077–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, E.P.; Tsai, T.; Barnett, S.A. A direct-methane fuel cell with a ceria-based anode. Nature 1999, 400, 649–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.H.; Zhai, T.; Cui, H.N.; Shi, J.Y.; Xie, S.L.; Huang, Y.Y.; Liang, C.L.; Tong, Y.X. Redox cycles promoting photocatalytic hydrogen evolution of CeO2 nanorods. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 5569–5572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xie, S.; Li, M.; Ouyang, X.; Cui, G.; Lu, X.; Tong, Y. CdS/CeOx heterostructured nanowires for photocatalytic hydrogen production. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 4190–4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, H.; Seo, Y.; Guillet-Nicolas, R.; Kaliaguinec, S.; Kleitz, F. One-step-impregnation hard templating synthesis of high-surface-area nanostructured mixed metal oxides (NiFe2O4, CuFe2O4 and Cu/CeO2). Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 10473–10475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Kailasam, K.; Xie, X.; Schomaecker, R.; Thomas, A. High-Surface-Area SBA-15 with Enhanced Mesopore Connectivity by the Addition of Poly(vinyl alcohol). Chem. Mater. 2011, 23, 2062–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunauer, S.; Deming, L.S.; Deming, W.E.; Teller, E. On a Theory of the van der Waals Adsorption of Gases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1940, 62, 1723–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikovitch, P.I.; Wei, D.; Chueh, W.T.; Haller, G.L.; Neimark, A.V. Evaluation of Pore Structure Parameters of MCM-41 Catalyst Supports and Catalysts by Means of Nitrogen and Argon Adsorption. J. Phys. Chem. B 1997, 101, 3671–3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, A. The Scherrer Formula for X-Ray Particle Size Determination. Phys. Rev. 1939, 56, 978–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouquerol, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S.W. Adsorption by Powders and Porous Solids. Principles Methodology and Applications; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Araújo, V.D.; Avansi, W.; de Carvalho, H.B.; Moreira, M.L.; Longo, E.; Ribeiroand, C.; Bernardi, M.I.B. CeO2 nanoparticles synthesized by a microwave-assisted hydrothermal method: Evolution from nanospheres to nanorods. CrystEngComm 2012, 14, 1150–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Zheng, D.; Zhang, P.; Liang, C.; Liu, P.; Tong, Y. Facile synthesis of free-standing CeO2 nanorods for photoelectrochemical applications. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 7721–7723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taniguchi, T.; Watanabe, T.; Sugiyama, N.; Subramani, A.K.; Wagata, H.; Matsushita, N.; Yoshimura, M. Identifying Defects in Ceria-Based Nanocrystals by UV Resonance Raman Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 19789–19793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhou, Q.; Fei, X.; He, Y.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, G.; Peng, L.; Xie, W. Synthesis of CuO nano- and micro-structures and their Raman spectroscopic studies. CrystEngComm 2010, 12, 2232–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lin, S.; Han, Z.; Liu, Y. Glutamine-assisted synthesis of Cu-doped CeO2 nanowires with an improved low-temperature CO oxidation activity. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 28619–28623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Yu, Y.; Zhou, W.; Xua, X.; Zhu, Z. Highly defective CeO2 as a promoter for efficient and stable water oxidation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, J.; Kibria, M.G.; Mi, Z.; Chaker, M.; Ma, D.; Nechache, R.; Rosei, F. Remarkably enhanced photocatalytic activity of laser ablated Au nanoparticle decorated BiFeO3 nanowires under visible-light. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 5856–5858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konta, R.; Ishii, T.; Kato, H.; Kudo, A. Photocatalytic Activities of Noble Metal Ion Doped SrTiO3 under Visible Light Irradiation. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 8992–8995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primo, A.; Marino, T.; Corma, A.; Molinari, R.; García, H. Efficient Visible-Light Photocatalytic Water Splitting by Minute Amounts of Gold Supported on Nanoparticulate CeO2 Obtained by a Biopolymer Templating Method. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 6930–6933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Markoulaki Ι, V.; Papadas, I.T.; Kornarakis, I.; Armatas, G.S. Synthesis of Ordered Mesoporous CuO/CeO2 Composite Frameworks as Anode Catalysts for Water Oxidation. Nanomaterials 2015, 5, 1971-1984. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano5041971

Markoulaki Ι V, Papadas IT, Kornarakis I, Armatas GS. Synthesis of Ordered Mesoporous CuO/CeO2 Composite Frameworks as Anode Catalysts for Water Oxidation. Nanomaterials. 2015; 5(4):1971-1984. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano5041971

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarkoulaki Ι, Vassiliki, Ioannis T. Papadas, Ioannis Kornarakis, and Gerasimos S. Armatas. 2015. "Synthesis of Ordered Mesoporous CuO/CeO2 Composite Frameworks as Anode Catalysts for Water Oxidation" Nanomaterials 5, no. 4: 1971-1984. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano5041971