Magneto-Plasmonics and Resonant Interaction of Light with Dynamic Magnetisation in Metallic and All-Magneto-Dielectric Nanostructures

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Magneto-Plasmonics

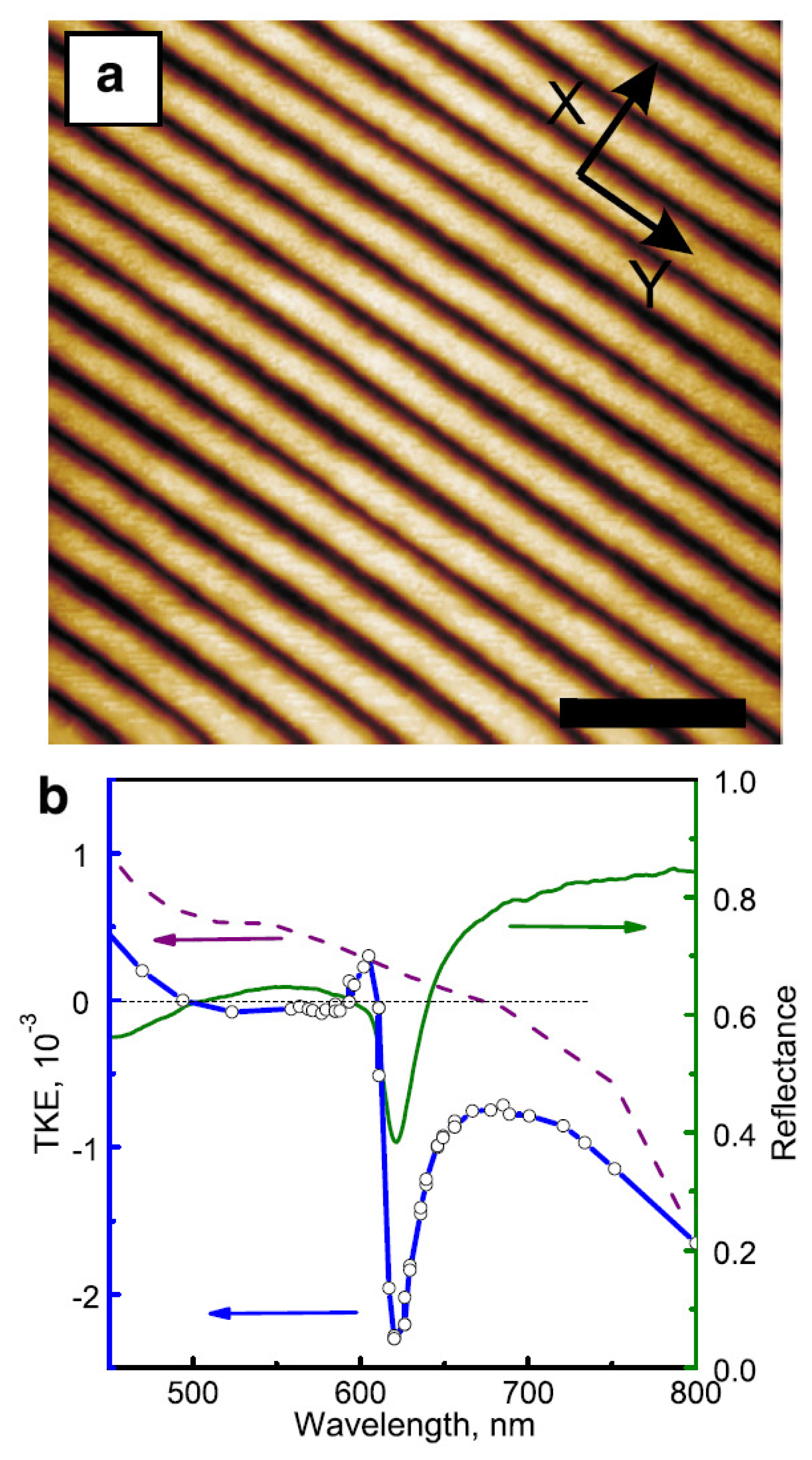

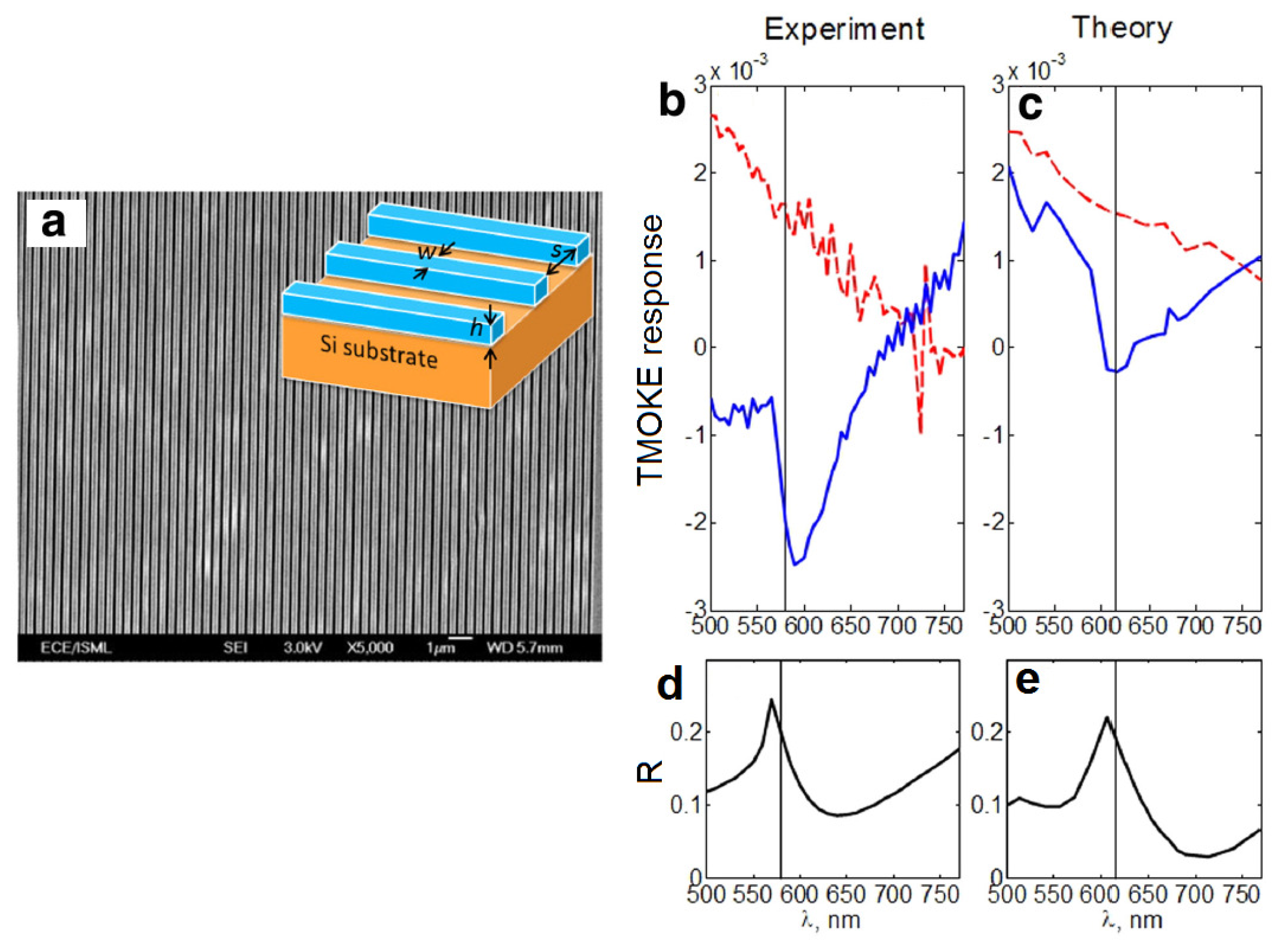

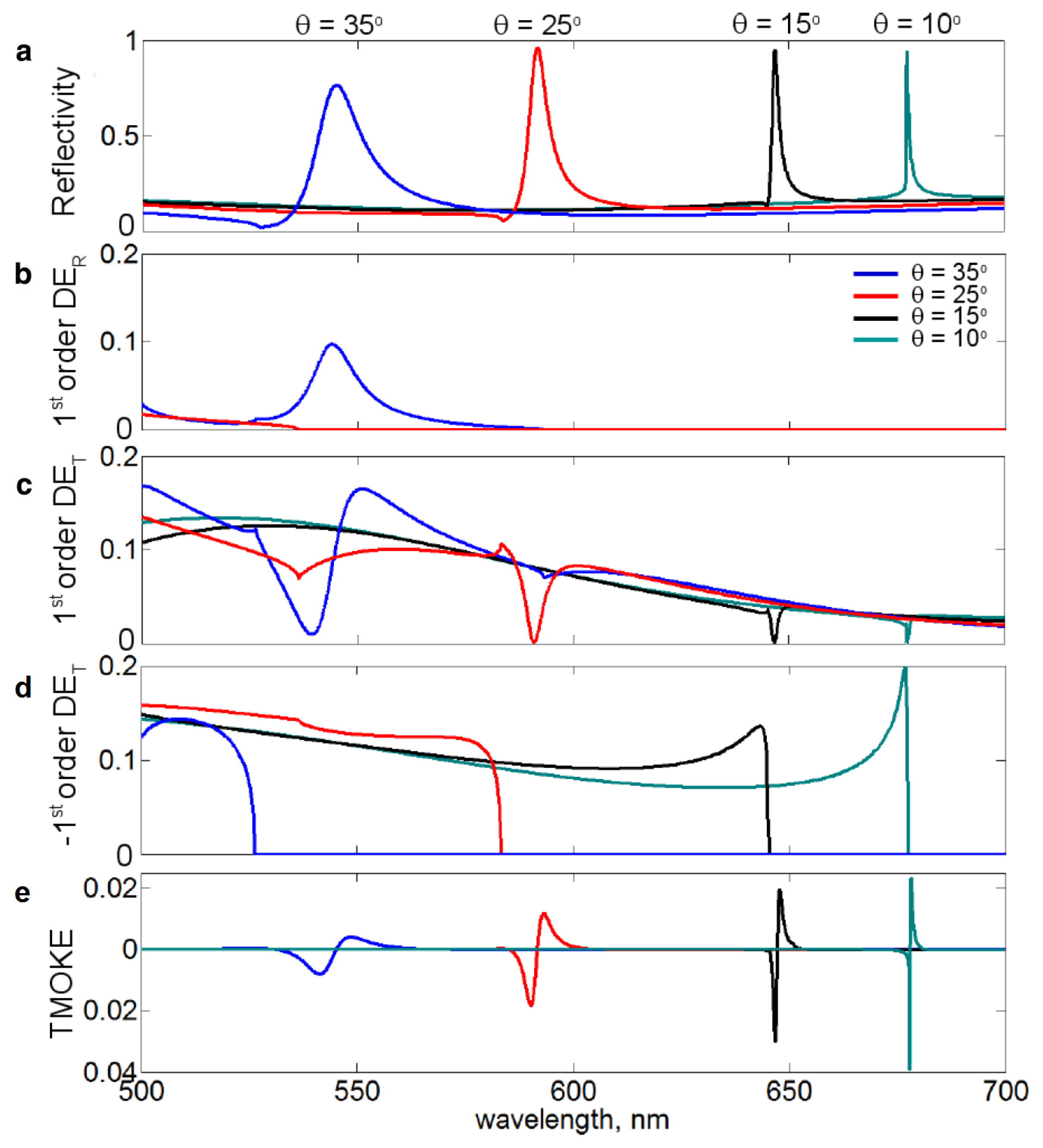

2.1. Plasmon-Enhanced Transverse Magneto-Optical Kerr Effect

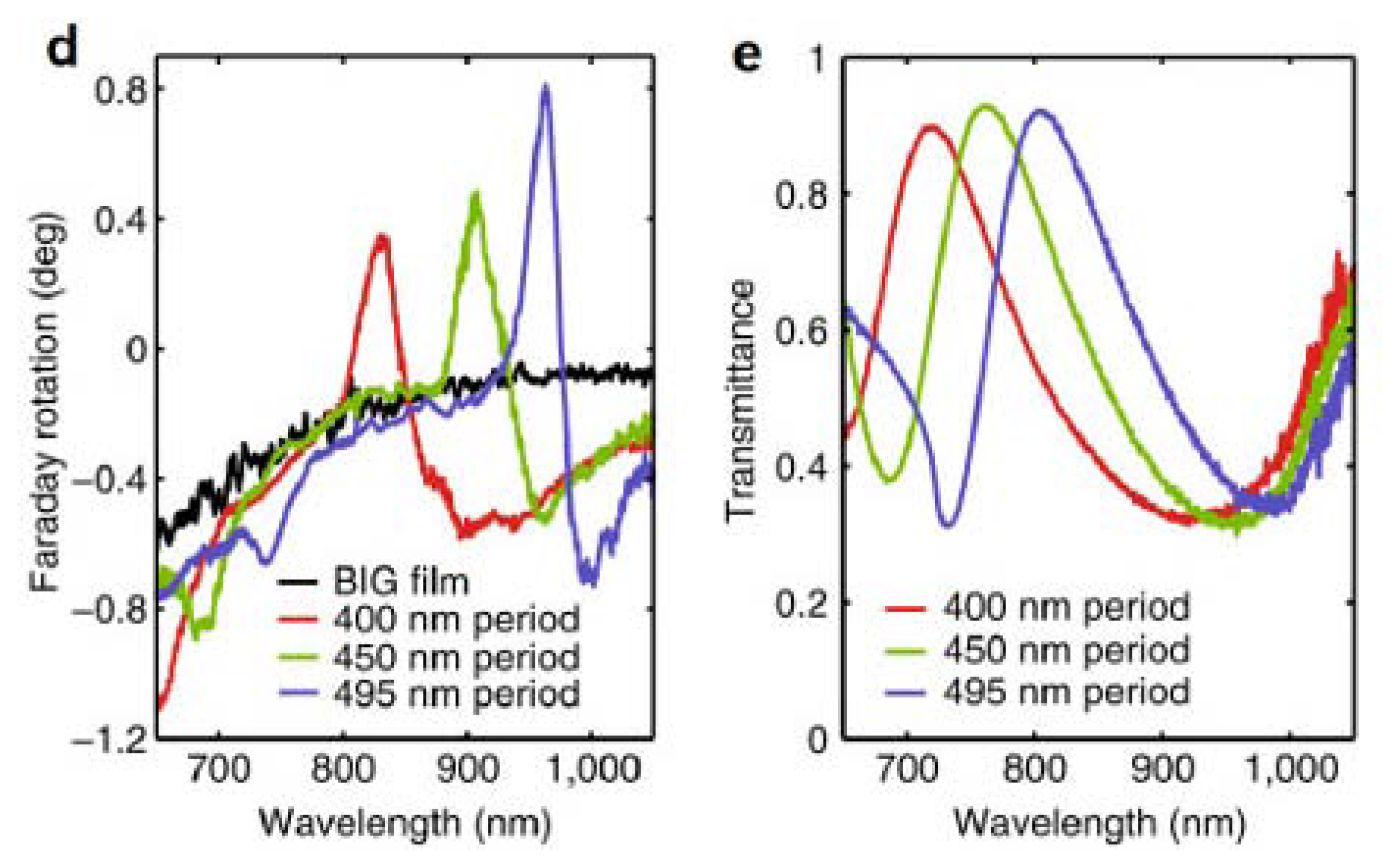

2.2. Plasmon-Enhanced Faraday Effect

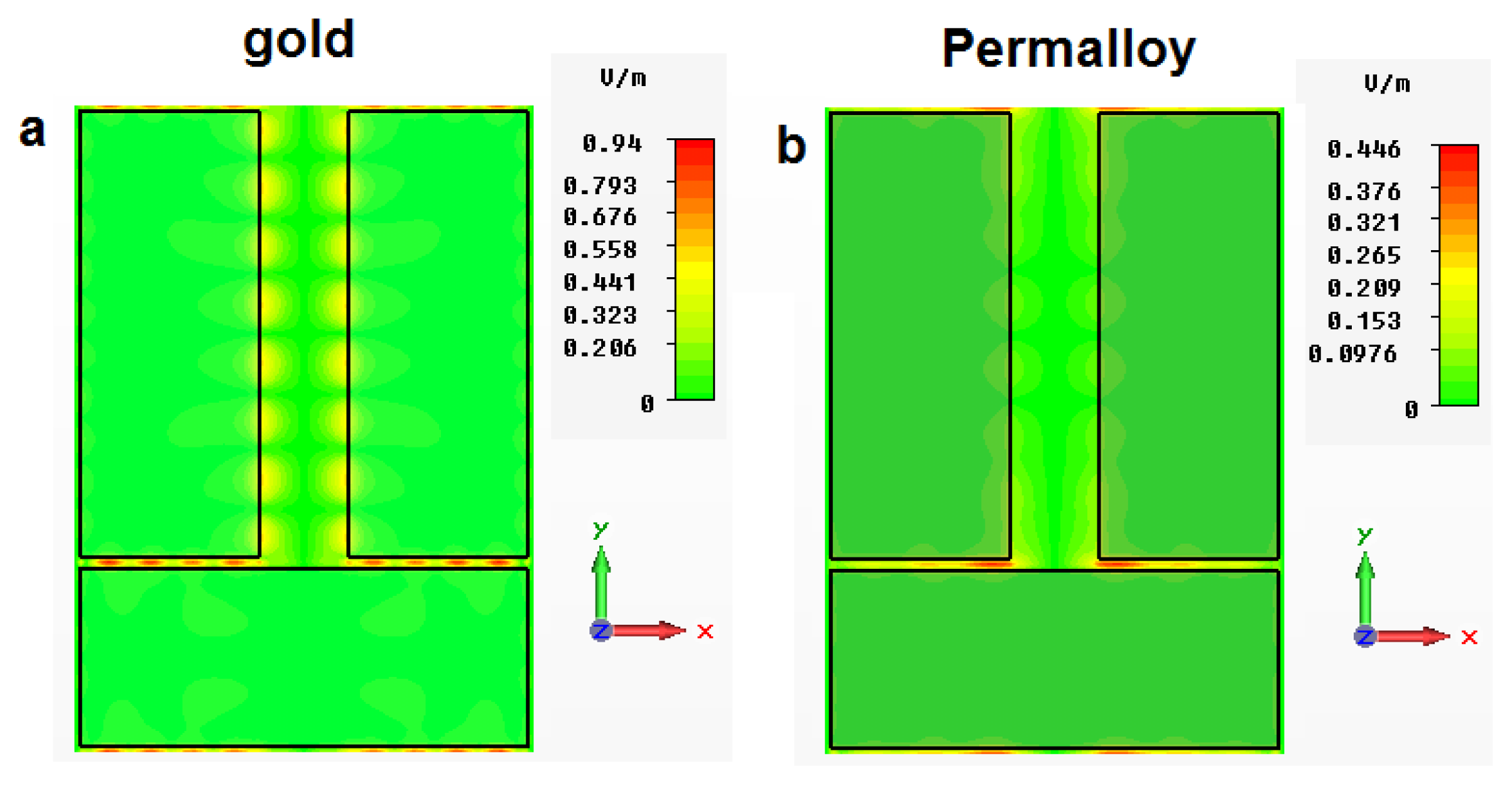

2.3. Plasmon-Enhanced TMOKE in All-Ferromagnetic Nanostructures

2.4. Longitudinal Magneto-Photonic Intensity Effect

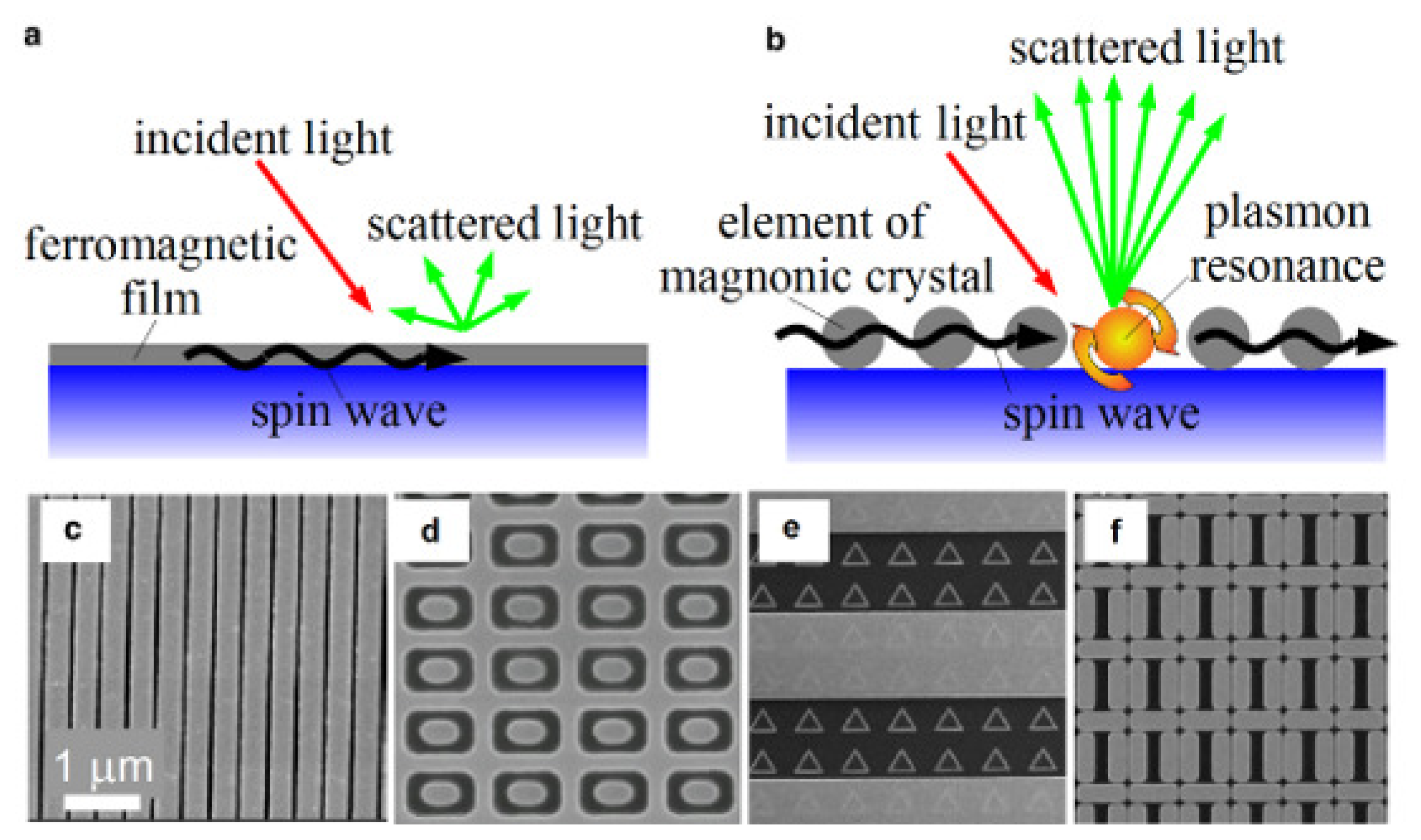

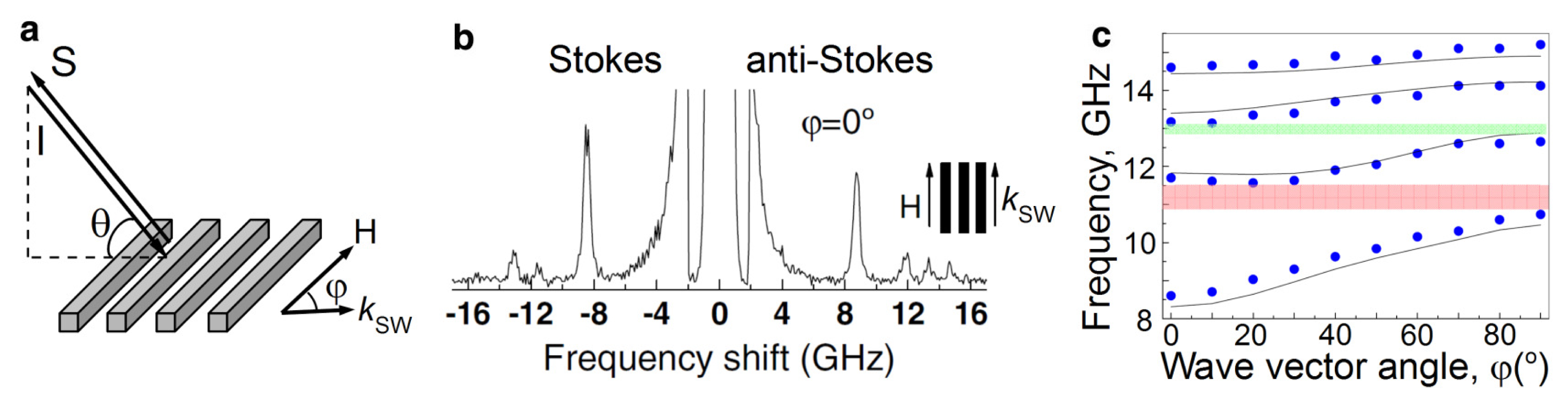

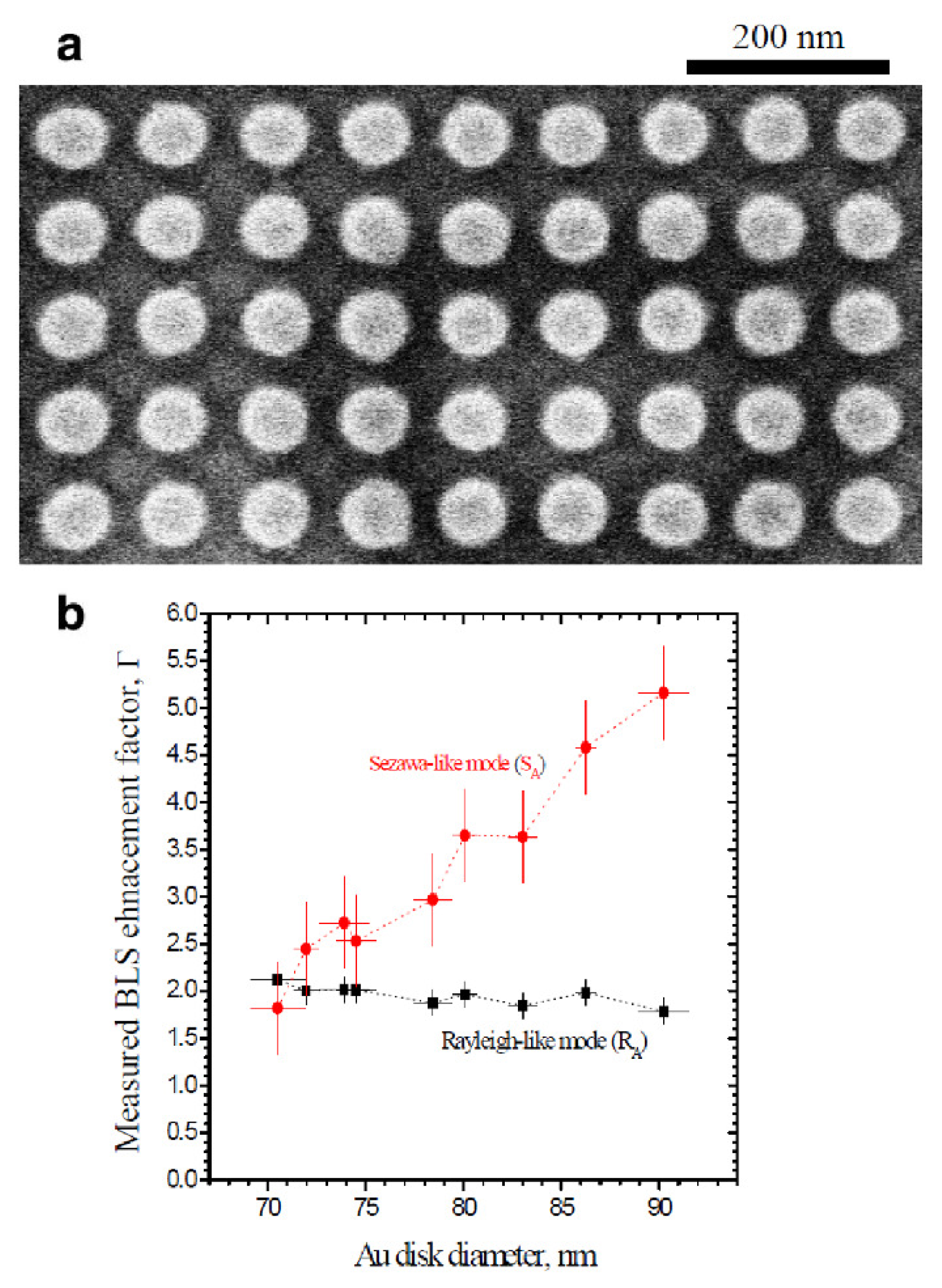

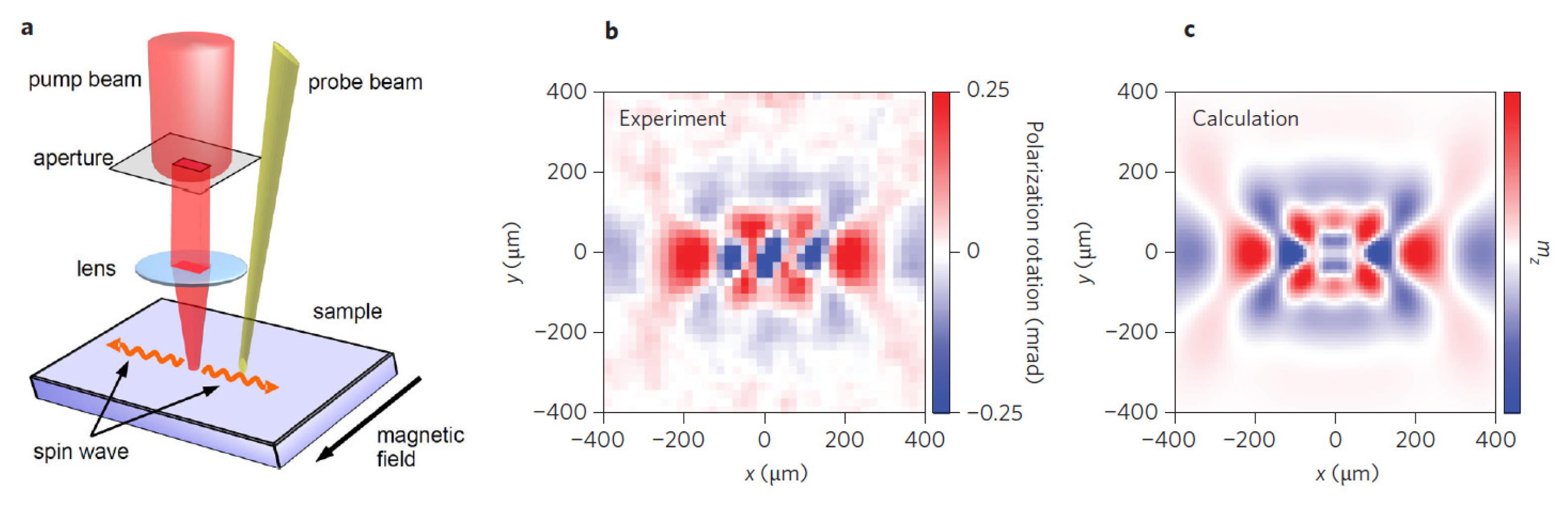

3. Perspectives of Magneto-Plasmonics in Spin-Wave and Magnonic Applications

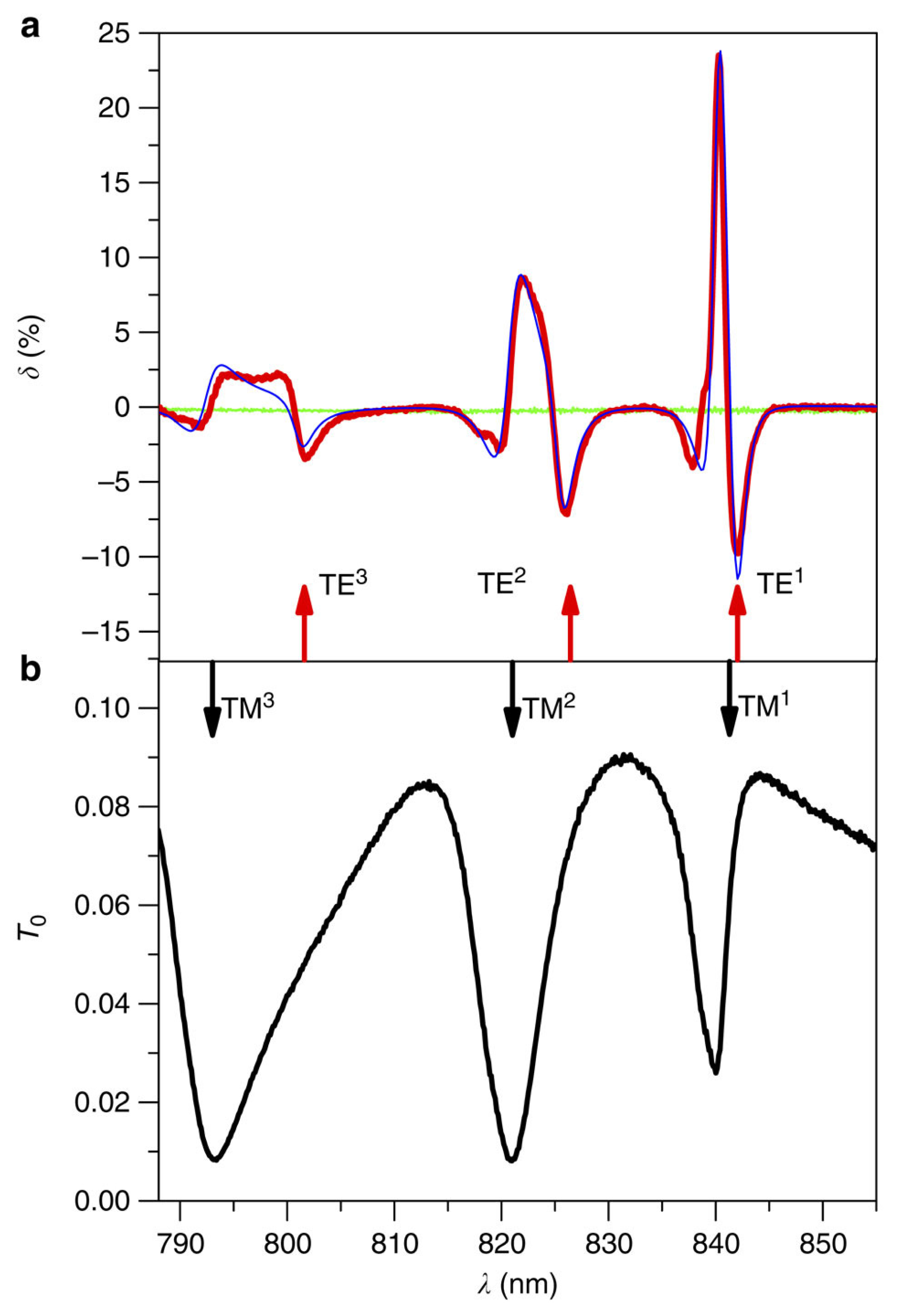

4. Enhanced Magneto-Optical effects in All-Magneto-Dielectric Nanostructures

5. Plasmon-Enhanced Inverse Magneto-Optical Effects and All-Optical Magnetisation Switching

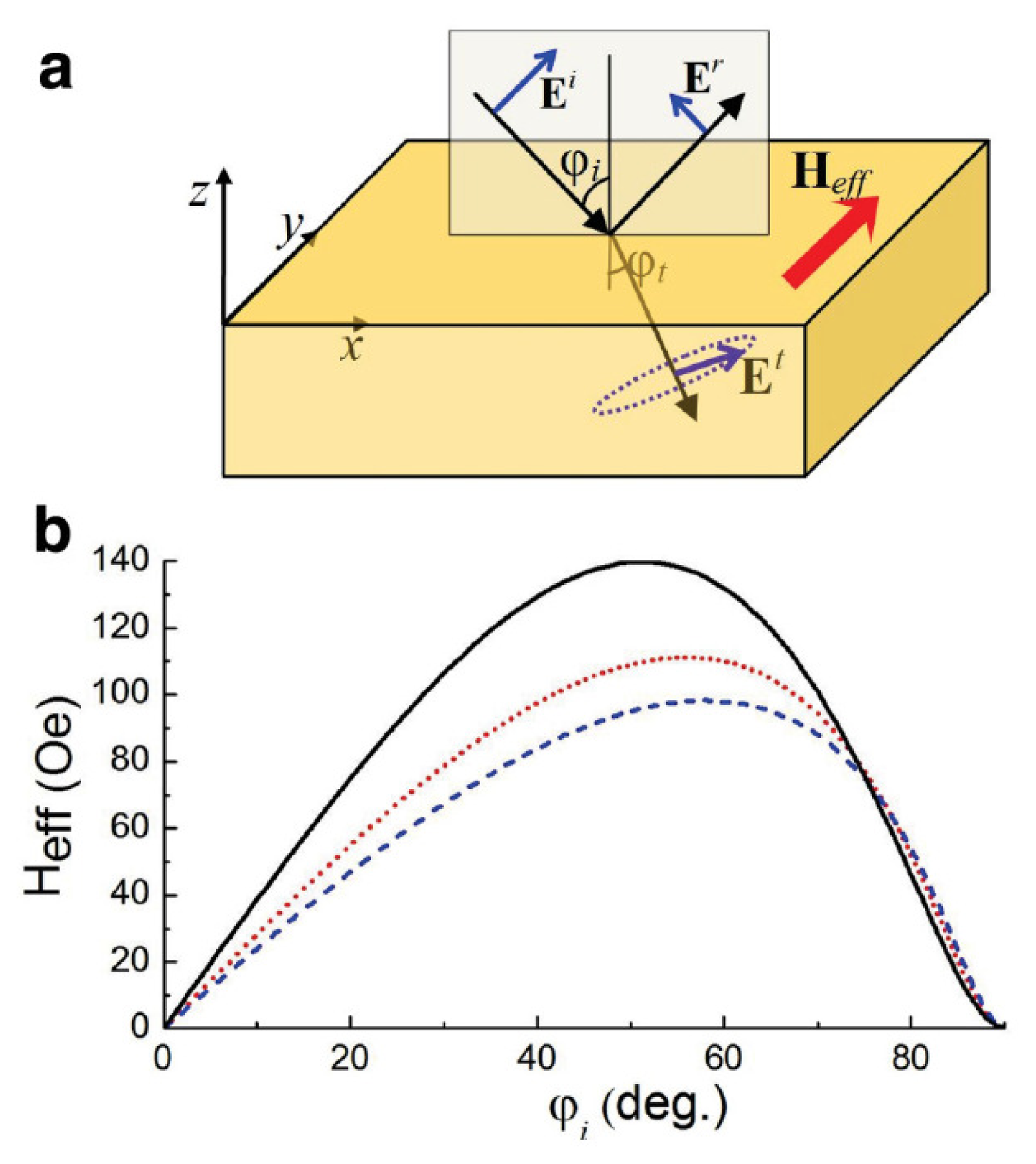

5.1. Plasmon-Enhanced Inverse Faraday Effect

5.2. Plasmon-Enhanced Inverse Transverse Magneto-Optical Effect

6. Perspectives of Terahertz Magneto-Plasmonics in Ultrafast Control of Dynamic Magnetisation

7. Relevant Topics

8. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- A sunny outlook. Nat Photon 2012, 6, 129.

- The Nobel Prize in Physics 2014 - Press release 2014.

- Aoshima, K.; Funabashi, N.; Machida, K.; Miyamoto, Y.; Kuga, K.; Ishibashi, T.; Shimidzu, N.; Sato, F. Submicron magneto-optical spatial light modulation device for holographic displays driven by spin-polarized electrons. J Disp Technol 2010, 6, 374–380. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, K.; van Soest, G.; van der Steen, A.F. Intravascular Photoacoustic Imaging: A New Tool for Vulnerable Plaque Identification. Ultrasound Med Biol 2014, 40, 1037–1048. [Google Scholar]

- Simply silicon. Nat Photon 2010, 4, 491.

- Almeida, V.R.; Barrios, C.A.; Panepucci, R.R.; Lipson, M. All-optical control of light on a silicon chip. Nature 2004, 431, 1081–1084. [Google Scholar]

- Vivien, L.; Pavesi, L. Handbook of Silicon Photonics; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schaller, R. Moore’s law: Past, present and future. IEEE Spectr 1997, 34, 52–59. [Google Scholar]

- Zhirnov, V.; Cavin, R.; Hutchby, J.; Bourianoff, G. Limits to binary logic switch scaling—A gedanken model. Proc IEEE 2003, 91, 1934–1939. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W.; Lieber, C.M. Nanoelectronics from the bottom up. Nat Mater 2007, 6, 841–850. [Google Scholar]

- Wallquist, M.; Hammerer, K.; Rabl, P.; Lukin, M.; Zoller, P. Hybrid quantum devices and quantum engineering. Phys Scripta 2009, 2009, 014001. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Z.L.; Ashhab, S.; You, J.Q.; Nori, F. Hybrid quantum circuits: Superconducting circuits interacting with other quantum systems. Rev Mod Phys 2013, 85, 623–653. [Google Scholar]

- Savage, N. Linking with light. IEEE Spectr 2002, 39, 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsey, N.; Ferrera, M.; Shalaev, V.M.; Boltasseva, A. Examining nanophotonics for integrated hybrid systems: A review of plasmonic interconnects and modulators using traditional and alternative materials. J Opt Soc Am B 2015, 32, 121–142. [Google Scholar]

- Willner, A.E.; Khaleghi, S.; Chitgarha, M.R.; Yilmaz, O.F. All-Optical Signal Processing. J Lightwave Technol 2014, 32, 660–680. [Google Scholar]

- Andryieuski, A.; Lavrinenko, A.V. Nanocouplers for Infrared and Visible Light. Adv Optoelectron 2012, 2012, 839747. [Google Scholar]

- Kruglyak, V.V.; Demokritov, S.O.; Grundler, D. Magnonics. J Phys D Appl Phys 2010, 43, 264001. [Google Scholar]

- Serga, A.A.; Chumak, A.V.; Hillebrands, B. YIG magnonics. J Phys D Appl Phys 2010, 43, 264002. [Google Scholar]

- Gubbiotti, G.; Tacchi, S.; Madami, M.; Carlotti, G.; Adeyeye, A.O.; Kostylev, M. Brillouin light scattering studies of planar metallic magnonic crystals. J Phys D Appl Phys 2010, 43, 264003. [Google Scholar]

- Lenk, B.; Ulrichs, H.; Garbs, F.; Münzenberg, M. The building blocks of magnonics. Phys Rep 2011, 507, 107–136. [Google Scholar]

- Stamps, R.L.; Breitkreutz, S.; Åkerman, J.; Chumak, A.V.; Otani, Y.; Bauer, G.E.W.; Thiele, J.U.; Bowen, M.; Majetich, S.A.; Kläui, M.; et al. The 2014 Magnetism Roadmap. J Phys D 2014, 47, 333001. [Google Scholar]

- Hirohata, A.; Takanashi, K. Future perspectives for spintronic devices. J Phys D 47, 01.

- Krawczyk, M.; Grundler, D. Review and prospects of magnonic crystals and devices with reprogrammable band structure. J Phys Cond Matter 2014, 26, 123202. [Google Scholar]

- Demokritov, S.O.; Slavin, A.N. Magnonics: From Fundamentals to Applications; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zvezdin, A.K.; Kotov, V.A. Modern Magnetooptics and Magnetooptical Materials; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Stancil, D.D.; Prabhakar, A. SpinWaves: Theory and Applications; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, W.L.; Dereux, A.; Ebbesen, T.W. Surface plasmon subwavelength optics. Nature 2003, 424, 824–830. [Google Scholar]

- Stockman, M.I. Nanoplasmonics: past, present, and glimpse into future. Opt Express 2011, 19, 22029–22106. [Google Scholar]

- Zayats, A.V.; Maier, S.A. Active Plasmonics and Tuneable Plasmonic Metamaterials; John Wiley and Sons: New Jersey, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Krasnok, A.E.; Maksymov, I.S.; Denisyuk, A.I.; Belov, P.A.; Miroshnichenko, A.E.; Simovski, C.R.; Kivshar, Y.S. Optical nanoantennas. Phys Usp 2013, 56, 539–564. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, K.; Quinn, J. Magneto-plasma surface waves in solids. Il Nuovo Cimento B 1972, 10, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Armelles, G.; Cebollada, A.; García-Martín, A.; González, M.U. Magnetoplasmonics: Combining Magnetic and Plasmonic Functionalities. Adv Opt Mater 2013, 1, 10–35. [Google Scholar]

- Temnov, V.V. Ultrafast acousto-magneto-plasmonics. Nat Photon 2012, 6, 728–736. [Google Scholar]

- Armelles, G.; Dmitriev, A. Focus on magnetoplasmonics. New J Phys 2014, 16, 045012. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, M.; Levy, M.; Baryshev, A.V. Magnetophotonics: From Theory to Applications; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Belotelov, V.I.; Akimov, I.A.; Pohl, M.; Kotov, V.A.; Kasture, S.; Vengurlekar, A.S.; Gopal, A.V.; Yakovlev, D.R.; Zvezdin, A.K.; Bayer, M. Enhanced magneto-optical effects in magnetoplasmonic crystals. Nat Nanotech 2011, 6, 370–376. [Google Scholar]

- Wurtz, G.A.; Hendren, W.; Pollard, R.; Atkinson, R.; Guyader, L.L.; Kirilyuk, A.; Rasing, T.; Smolyaninov, I.I.; Zayats, A.V. Controlling optical transmission through magneto-plasmonic crystals with an external magnetic field. New J Phys 2008, 10, 105012. [Google Scholar]

- Belotelov, V.I.; Doskolovich, L.L.; Zvezdin, A.K. Extraordinary Magneto-Optical Effects and Transmission through Metal-Dielectric Plasmonic Systems. Phys Rev Lett 2007, 98, 077401. [Google Scholar]

- Belotelov, V.I.; Bykov, D.A.; Doskolovich, L.L.; Kalish, A.N.; Zvezdin, A.K. Extraordinary transmission and giant magneto-optical transverse Kerr effect in plasmonic nanostructured films. J Opt Soc Am B 2009, 26, 1594–1598. [Google Scholar]

- Kreilkamp, L.E.; Belotelov, V.I.; Chin, J.Y.; Neutzner, S.; Dregely, D.; Wehlus, T.; Akimov, I.A.; Bayer, M.; Stritzker, B.; Giessen, H. Waveguide-Plasmon Polaritons Enhance Transverse Magneto-Optical Kerr Effect. Phys Rev X 2013, 3, 041019. [Google Scholar]

- Christ, A.; Zentgraf, T.; Kuhl, J.; Tikhodeev, S.G.; Gippius, N.A.; Giessen, H. Optical properties of planar metallic photonic crystal structures: Experiment and theory. Phys Rev B 2004, 70, 125113. [Google Scholar]

- Mansuripur, M. The Faraday effect. Opt Photon News 1999, 10, 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, P.K.; Xiao, Y.; Walsworth, R.; Cohen, A.E. Surface Plasmon Resonance Enhanced Magneto-Optics (SuPREMO): Faraday Rotation Enhancement in Gold-Coated Iron Oxide Nanocrystals. Nano Lett 2009, 9, 1644–1650. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, J.Y.; Steinle, T.; Wehlus, T.; Dregely, D.; Weiss, T.; Belotelov, V.I.; Stritzker, B.; Giessen, H. Nonreciprocal plasmonics enables giant enhancement of thin-film Faraday rotation. Nat Commun 2013, 4, 1599. [Google Scholar]

- Wehlus, T.; Körner, T.; Leitenmeier, S.; Heinrich, A.; Stritzker, B. Magneto-optical garnets for integrated optoelectronic devices. Phys Status Solidi A 2011, 208, 252–263. [Google Scholar]

- Miroshnichenko, A.E.; Flach, S.; Kivshar, Y.S. Fano resonances in nanoscale structures. Rev Mod Phys 2010, 82, 2257–2298. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, C.H.; Mangin, S.; Varaprasad, B.S.D.C.S.; Takahashi, Y.K.; Hehn, M.; Cinchetti, M.; Malinowski, G.; Hono, K.; Fainman, Y.; Aeschlimann, M.; et al. All-optical control of ferromagnetic thin films and nanostructures. Science 2014, 345, 1337–1340. [Google Scholar]

- Mruczkiewicz, M.; Pavlov, E.; Vysotskii, S.; Krawczyk, M.; Filimonov, Y.; Nikitov, S. Magnonic Bandgaps in Metalized 1-D YIG Magnonic Crystals. IEEE Trans Magnet 2014, 50, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, L.; Hu, J.; Kimerling, L.; Ross, C.A. Fabrication and characterization of As2S3/Y3Fe5O12 and Y3Fe5O12/SOI strip-loaded waveguides for integrated optical isolator applications. Proc SPIE 2010, 7604, 760406–760406–10. [Google Scholar]

- Grunin, A.A.; Zhdanov, A.G.; Ezhov, A.A.; Ganshina, E.A.; Fedyanin, A.A. Surface-plasmon-induced enhancement of magneto-optical Kerr effect in all-nickel subwavelength nanogratings. Appl Phys Lett 2010, 97, 261908. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, D.M.; Wears, M.L.; Matelon, R.J.; Hooper, I.R. Magneto-optic behaviour in the presence of surface plasmons. J Phys: Cond Matter 2008, 20, 345230. [Google Scholar]

- Ctistis, G.; Papaioannou, E.; Patoka, P.; Gutek, J.; Fumagalli, P.; Giersig, M. Optical and Magnetic Properties of Hexagonal Arrays of Subwavelength Holes in Optically Thin Cobalt Films. Nano Lett 2009, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sapozhnikov, M.V.; Gusev, S.A.; Troitskii, B.B.; Khokhlova, L.V. Optical and magneto-optical resonances in nanocorrugated ferromagnetic films. Opt Lett 2011, 36, 4197–4199. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanni, V.; Bonetti, S.; Pakizeh, T.; Pirzadeh, Z.; Chen, J.; Nogués, J.; Vavassori, P.; Hillenbrand, R.; Åkerman, J.; Dmitriev, A. Designer Magnetoplasmonics with Nickel Nanoferromagnets. Nano Lett 2011, 11, 5333–5338. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Albella, P.; Pirzadeh, Z.; Alonso-González, P.; Huth, F.; Bonetti, S.; Bonanni, V.; Åkerman, J.; Nogués, J.; Vavassori, P.; et al. Plasmonic Nickel Nanoantennas. Small 2011, 7, 2341–2347. [Google Scholar]

- Chetvertukhin, A.V.; Baryshev, A.V.; Uchida, H.; Inoue, M.; Fedyanin, A.A. Resonant surface magnetoplasmons in two-dimensional magnetoplasmonic crystals excited in Faraday configuration. J Appl Phys 2012, 111, 07A946. [Google Scholar]

- Kostylev, N.; Maksymov, I.S.; Adeyeye, A.O.; Samarin, S.; Kostylev, M.; Williams, J.F. Plasmon-assisted high reflectivity and strong magneto-optical Kerr effect in permalloy gratings. Appl Phys Lett 2013, 102, 121907. [Google Scholar]

- Maccaferri, N.; Berger, A.; Bonetti, S.; Bonanni, V.; Kataja, M.; Qin, Q.H.; van Dijken, S.; Pirzadeh, Z.; Dmitriev, A.; Nogués, J.; et al. Tuning the Magneto-Optical Response of Nanosize Ferromagnetic Ni Disks Using the Phase of Localized Plasmons. Phys Rev Lett 2013, 111, 167401. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, D.M.; Wears, M.L.; Matelon, R.J. Plasmon transport phenomena on a continuous ferromagnetic surface. Europhys Lett 2004, 68, 692. [Google Scholar]

- Krutyanskiy, V.L.; Kolmychek, I.A.; Gan’shina, E.A.; Murzina, T.V.; Evans, P.; Pollard, R.; Stashkevich, A.A.; Wurtz, G.A.; Zayats, A.V. Plasmonic enhancement of nonlinear magneto-optical response in nickel nanorod metamaterials. Phys Rev B 2013, 87, 035116. [Google Scholar]

- Melander, E.; Östman, E.; Keller, J.; Schmidt, J.; Papaioannou, E.T.; Kapaklis, V.; Arnalds, U.B.; Caballero, B.; García-Martín, A.; Cuevas, J.C.; et al. Influence of the magnetic field on the plasmonic properties of transparent Ni anti-dot arrays. Appl Phys Lett 2012, 101, 063107. [Google Scholar]

- Chetvertukhin, A.V.; Grunin, A.A.; Baryshev, A.V.; Dolgova, T.V.; Uchida, H.; Inoue, M.; Fedyanin, A.A. Magneto-optical Kerr effect enhancement at the Wood’s anomaly in magnetoplasmonic crystals. J Magn Magn Mater 2012, 324, 3516–3518. [Google Scholar]

- Hessel, A.; Oliner, A.A. A New Theory of Wood’s Anomalies on Optical Gratings. Appl Opt 1965, 4, 1275–1297. [Google Scholar]

- Galli, M.; Portalupi, S.L.; Belotti, M.; Andreani, L.C.; O’Faolain, L.; Krauss, T.F. Light scattering and Fano resonances in high-Q photonic crystal nanocavities. Appl Phys Lett 2009, 94, 071101. [Google Scholar]

- Gallinet, B.; Martin, O.J.F. Ab initio theory of Fano resonances in plasmonic nanostructures and metamaterials. Phys Rev B 2011, 83, 235427. [Google Scholar]

- Maksymov, I.S.; Miroshnichenko, A.E. Active control over nanofocusing with nanorod plasmonic antennas. Opt Express 2011, 19, 5888–5894. [Google Scholar]

- Ichi Tanaka, S. Longitudinal Kerr Magneto-Optic Effect in Permalloy Film. Jap J Appl Phys 1963, 2, 548. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, C.C. Longitudinal Kerr Magneto-Optic Effect in Thin Films of Iron, Nickel, and Permalloy. J Opt Soc Am 1963, 53, 681–687. [Google Scholar]

- Krinchik, G.; Chepurova, E.; Kraeva, T. Magneto-optical effects in nickel and Permalloy associated with frustrated total internal reflection. Zh Eksp Teor Fiz 1985, 88, 277–285. [Google Scholar]

- Belotelov, V.I.; Kreilkamp, L.E.; Akimov, I.A.; Kalish, A.N.; Bykov, D.A.; Kasture, S.; Yallapragada, V.J.; Gopal, A.V.; Grishin, A.M.; Khartsev, S.I.; et al. Plasmon-mediated magneto-optical transparency. Nat Commun 2013, 4, 2128. [Google Scholar]

- Krinchik, G.; Gushchin, G.S. Magnetooptical effect of change of electronic structure of a ferromagnetic metal following rotation of the magnetization vector. JETP Lett 1969, 10, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kurp, P. Green Computing. Commun ACM 2008, 51, 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Samad, J.; Kumar, R. Computers and global warming. Int J Eng Innov Technol 2013, 2, 241–244. [Google Scholar]

- Hertel, R.; Wulfhekel, W.; Kirschner, J. Domain-Wall Induced Phase Shifts in Spin Waves. Phys Rev Lett 2004, 93, 257202. [Google Scholar]

- Kostylev, M.P.; Serga, A.A.; Schneider, T.; Leven, B.; Hillebrands, B. Spin-wave logical gates. Appl Phys Lett 2005, 87, 153501. [Google Scholar]

- Hertel, R. Guided Spin Waves. Handbook of Magnetism and Advanced Magnetic Materials; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, T.; Serga, A.A.; Leven, B.; Hillebrands, B.; Stamps, R.L.; Kostylev, M.P. Realization of spin-wave logic gates. Appl Phys Lett 2008, 92, 022505. [Google Scholar]

- Khitun, A.; Bao, M.; Wang, K.L. Magnonic logic circuits. J Phys D 2010, 43, 264005. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, J.; Kostylev, M.; Adeyeye, A.O. Realization of a mesoscopic reprogrammable magnetic logic based on a nanoscale reconfigurable magnonic crystal. Appl Phys Lett 2012, 100, 073114. [Google Scholar]

- Demokritov, S.O. Spin Wave Confinement; Pan Stanford Publishing: Singapore, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Maksymov, I.S.; Kostylev, M. Broadband stripline ferromagnetic resonance spectroscopy of ferromagnetic films, multilayers and nanostructures. Phys E 2015, 69, 253–293. [Google Scholar]

- Wehrspohn, H.S.K.; Busch, K. Nanophotonic Materials: Photonic Crystals, Plasmonics, and Metamaterials; Wiley-VCH Verlag: Weinheim, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- The International Technology Roadmap for Semiconductors (ITRS); Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA): Washington, DC, USA, 2011.

- Kirilyuk, A.; Kimel, A.V.; Rasing, T. Ultrafast optical manipulation of magnetic order. Rev Mod Phys 2010, 82, 2731–2784. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, M. Chirped-microwave assisted magnetization reversal. J Appl Phys 2009, 105, 093903. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, J. Novel Magnonic Crystals and Devices: Fabrication, Static and Dynamic Behaviors; Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, National University of Singapore: Singapore, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, J.; Kostylev, M.; Adeyeye, A.O. Broadband ferromagnetic resonance spectroscopy of permalloy triangular nanorings. Appl Phys Lett 2012, 100, 062401. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, J.; Singh, N.; Kostylev, M.; Adeyeye, A.O. Static and dynamic magnetic properties of Ni80Fe20 anti-ring nanostructures. Phys Rev B 2013, 88, 014301. [Google Scholar]

- Kostylev, M.; Zhong, S.; Ding, J.; Adeyeye, A.O. Resonance properties of bi-component arrays of magnetic dots magnetized perpendicular to their planes. J Appl Phys 2013, 114, 113910. [Google Scholar]

- Raether, H. Surface Plasmons on Smooth and Rough Surfaces and on Gratings; Springer Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Adeyeye, A.O.; Singh, N. Large area patterned magnetic nanostructures. J Phys D 2008, 41, 153001. [Google Scholar]

- Verellen, N.; Sonnefraud, Y.; Sobhani, H.; Hao, F.; Moshchalkov, V.V.; Dorpe, P.V.; Nordlander, P.; Maier, S.A. Fano Resonances in Individual Coherent Plasmonic Nanocavities. Nano Lett 2009, 9, 1663–1667. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, A.D.; Melo, L.G.C.; Martins, C.S.; Missell, F.P.; Souche, Y.; Machado, F.L.A.; Rezende, S.M. Domains and giant magneto-impedance in amorphous ribbons by magneto-optical Kerr effect. J Appl Phys 1996, 79, 6546–6548. [Google Scholar]

- Vavassori, P. Polarization modulation technique for magneto-optical quantitative vector magnetometry. Appl Phys Lett 2000, 77, 1605–1607. [Google Scholar]

- Gubbiotti, G.; Tacchi, S.; Carlotti, G.; Vavassori, P.; Singh, N.; Goolaup, S.; Adeyeye, A.O.; Stashkevich, A.; Kostylev, M. Magnetostatic interaction in arrays of nanometric permalloy wires: A magneto-optic Kerr effect and a Brillouin light scattering study. Phys Rev B 2005, 72, 224413. [Google Scholar]

- Willig, L. Magnetisation Dynamics and Magneto-Optics of Nanostructures. Master Thesis, School of Physics, University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Demokritov, S.; Tsymbal, E. Light scattering from spin waves in thin films and layered systems. J Phys 1994, 6, 7145. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y. Modern Techniques for Characterizing Magnetic Materials; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kronmüller, H.; Parkin, S. Handbook of Magnetism and Advanced Magnetic Materials; Wiley-Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Borovik-Romanov, A.S.; Kreines, N.M. Brillouin-Mandelstam scattering from thermal and excited magnons. Phys Rep 1982, 81, 351–408. [Google Scholar]

- Fukui, M.; Tada, O.; So, V.C.Y.; Stegeman, G.I. Enhanced Brillouin scattering involving surface plasmon polaritons. J Phys C 1981, 14, 5591. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Hillebrands, B.; Dutcher, J.R.; Stegeman, G.I.; Knoll, W.; Nizzoli, F. Dispersion and localization of guided acoustic modes in a Langmuir-Blodgett film studied by surface-plasmon-polariton-enhanced Brillouin scattering. Phys Rev B 1990, 41, 5382–5387. [Google Scholar]

- Utegulov, Z.N.; Shaw, J.M.; Draine, B.T.; Kim, S.A.; Johnson, W.L. Surface-plasmon enhancement of Brillouin light scattering from gold-nanodisk arrays on glass. Proc SPIE 2007, 6641, 66411M:1–66411M:10. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, W.L.; Kim, S.A.; Utegulov, Z.N.; Shaw, J.M.; Draine, B.T. Optimization of Arrays of Gold Nanodisks for Plasmon-Mediated Brillouin Light Scattering. J Phys Chem C 2009, 113, 14651–14657. [Google Scholar]

- Van Exter, M.; Lagendijk, A. Ultrashort Surface-Plasmon and Phonon Dynamics. Phys Rev Lett 1988, 60, 49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wu, J.; Guo, C. Resolving dynamics of acoustic phonons by surface plasmons. Opt Lett 2007, 32, 719–721. [Google Scholar]

- Khokhlov, N.E. Resonant Optical Effects Resulting from Optical, Magnetic and Acoustic Control of Plasmon-Polaritons in Multilayered Structures (in Russian). PhD Thesis, Department of Photonics and Microwave Physics, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.S.; Magnusson, R. Theory and applications of guided-mode resonance filters. Appl Opt 1993, 32, 2606–2613. [Google Scholar]

- Naik, G.V.; Shalaev, V.M.; Boltasseva, A. Alternative Plasmonic Materials: Beyond Gold and Silver. Adv Mater 2013, 25, 3264–3294. [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsov, A.I.; Miroshnichenko, A.E.; Fu, Y.H.; Zhang, J.; Luk’yanchuk, B. Magnetic light. Sci Rep 2012, 2, 492. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, B.; Tervo, J.; Turunen, J. Polarization conversion in resonant magneto-optic gratings. New J Phys 2006, 8, 205. [Google Scholar]

- Marinchio, H.; Carminati, R.; García-Martín, A.; Sáenz, J.J. Magneto-optical Kerr effect in resonant subwavelength nanowire gratings. New J Phys 2014, 16, 015007. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, J.; Deng, L.; Xie, J.; Tang, T.; Bi, L. Highly sensitive sensors based on magneto-optical surface plasmon resonance in Ag/CeYIG heterostructures. AIP Adv 2015, 5, 017118. [Google Scholar]

- Souche, Y.; Novosad, V.; Pannetier, B.; Geoffroy, O. Magneto-optical diffraction and transverse Kerr effect. J Magn Magn Mater 1998, 177–181, 1277–1278. [Google Scholar]

- Amemiya, T.; Ishikawa, A.; Shoji, Y.; Hai, P.N.; Tanaka, M.; Mizumoto, T.; Tanaka, T.; Arai, S. Three-dimensional nanostructuring in YIG ferrite with femtosecond laser. Opt Lett 2014, 39, 212–215. [Google Scholar]

- Maksymov, I.S.; Hutomo, J.; Kostylev, M. Transverse magneto-optical Kerr effect in subwavelength dielectric gratings. Opt Express 2014, 22, 8720–8725. [Google Scholar]

- Khokhlov, N.E.; Prokopov, A.R.; Shaposhnikov, A.N.; Berzhansky, V.N.; Kozhaev, M.A.; Andreev, S.N.; Ravishankar, A.P.; Achanta, V.G.; Bykov, D.A.; Zvezdin, A.K.; et al. Photonic crystals with plasmonic patterns: Novel type of the heterostructures for enhanced magneto-optical activity. J Phys D 2015, 48, 095001. [Google Scholar]

- Kimel, A.V.; Kirilyuk, A.; Usachev, P.A.; Pisarev, R.V.; Balbashov, A.M.; Rasing, T. Ultrafast non-thermal control of magnetization by instantaneous photomagnetic pulses. Nature 2005, 435, 655–657. [Google Scholar]

- Vabishchevich, P.P.; Frolov, A.Y.; Shcherbakov, M.R.; Grunin, A.A.; Dolgova, T.V.; Fedyanin, A.A. Magnetic field-controlled femtosecond pulse shaping by magnetoplasmonic crystals. J Appl Phys 2013, 113, 17A947. [Google Scholar]

- Shcherbakov, M.R.; Vabishchevich, P.P.; Frolov, A.Y.; Dolgova, T.V.; Fedyanin, A.A. Femtosecond intrapulse evolution of the magneto-optic Kerr effect in magnetoplasmonic crystals. Phys Rev B 90, 05.

- Satoh, T.; Terui, Y.; Moriya, R.; Ivanov, B.A.; Ando, K.; Saitoh, E.; Shimura, T.; Kuroda, K. Directional control of spin wave emission by spatially shaped light. Nat Photon 2012, 6, 662–666. [Google Scholar]

- Pitaevskii, L.P. Electric Forces in a Transparent Dispersive Medium. Sov Phys JETP 1961, 12, 1008–1013. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Ziel, J.P.; Pershan, P.S.; Malmstrom, L.D. Optically-Induced Magnetization Resulting from the Inverse Faraday Effect. Phys Rev Lett 1965, 15, 190–193. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo, C.; Dupays, A.; Battesti, R.; Fouché, M.; Rikken, G.L.J.A. Inverse Cotton-Mouton effect of the vacuum and of atomic systems. Europhys Lett 2010, 90, 64003. [Google Scholar]

- Popov, S.V.; Svirko, Y.P.; Zheludev, N.I. Coherent and incoherent specular inverse Faraday effect: χ(3) measurements in opaque materials. Opt Lett 1994, 19, 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Perroni, C.A.; Liebsch, A. Coherent control of magnetization via inverse Faraday effect. J Phys 2006, 18, 7063. [Google Scholar]

- Hertel, R. Microscopic theory of the inverse Faraday effect. ArXiv E-Prints 2005. arXiv:cond-mat/0509060. [Google Scholar]

- Satoh, T. Opto-magnonics: Light pulses manipulating spin waves. SPIE Newsroom 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stipe, B.C.; Strand1, T.C.; Poon, C.C.; Balamane, H.; Boone, T.D.; Katine, J.A.; Li, J.L.; Rawat, V.; Nemoto, H.; Hirotsune, A.; et al. Magnetic recording at 1.5 Pb m2 using an integrated plasmonic antenna. Nat Photon 2010, 4, 484–488. [Google Scholar]

- Guyader, L.L.; Savoini, M.; Moussaoui, S.E.; Buzzi, M.; Tsukamoto; Itoh, A.; Kirilyuk, A.; Rasing, T.; Kimel, A.; Nolting, F. Nanoscale sub-100 picosecond all-optical magnetization switching in GdFeCo microstructures. Nat Commun 2015, 6, 5839. [Google Scholar]

- Maksymov, I.S.; Staude, I.; Miroshnichenko, A.E.; Kivshar, Y.S. Optical Yagi-Uda nanoantennas. Nanophotonics 2012, 1, 65–81. [Google Scholar]

- Stannigel, K.; Komar, P.; Habraken, S.J.M.; Bennett, S.D.; Lukin, M.D.; Zoller, P.; Rabl, P. Optomechanical Quantum Information Processing with Photons and Phonons. Phys Rev Lett 2012, 109, 013603. [Google Scholar]

- Belotelov, V.I.; Zvezdin, A.K. Inverse transverse magneto-optical Kerr effect. Phys Rev B 2012, 86, 155133. [Google Scholar]

- Pohl, M.; Kreilkamp, L.E.; Belotelov, V.I.; Akimov, I.A.; Kalish, A.N.; Khokhlov, N.E.; Yallapragada, V.J.; Gopal, A.V.; Nur-E-Alam, M.; Vasiliev, M.; et al. Tuning of the transverse magneto-optical Kerr effect in magneto-plasmonic crystals. New J Phys 2013, 15, 075024. [Google Scholar]

- Mittleman, D.M. Frontiers in terahertz sources and plasmonics. Nat Photon 2013, 7, 666–669. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Mittleman, D.M. Metal wires for terahertz wave guiding. Nature 2004, 432, 376–379. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Lakhtakia, A.; Tian, Z.; Lu, X.; Zhang, W. Magnetic and magnetothermal tunabilities of subwavelength-hole arrays in a semiconductor sheet. Opt Lett 2009, 34, 1465–1467. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, Y.C.; Chang, Y.C.; Lee, P.H. Manipulation of tunneling frequencies using magnetic fields for resonant tunneling effects of surface plasmons. Appl Phys Lett 2007, 90, 171114. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, G.; Li, S.; Jadidi, M.M.; Murphy, T.E. Terahertz surface plasmon waveguide based on a one-dimensional array of silicon pillars. New J Phys 2013, 15, 085031. [Google Scholar]

- Cong, L.; Cao, W.; Tian, Z.; Gu, J.; Han, J.; Zhang, W. Manipulating polarization states of terahertz radiation using metamaterials. New J Phys 2012, 14, 115013. [Google Scholar]

- Tsiatmas, A.; Fedotov, V.A.; de Abajo, F.J.G.; Zheludev, N.I. Low-loss terahertz superconducting plasmonics. New J Phys 2012, 14, 115006. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, C.W.; Jarrahi, M. Terahertz generation using plasmonic photoconductive gratings. New J Phys 2012, 14, 105029. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, B.; Wang, Q.J.; Zhang, Y. Broadly tunable one-way terahertz plasmonic waveguide based on nonreciprocal surface magneto plasmons. Opt Lett 2012, 37, 1895–1897. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, F.; Chang, S.J.; Gu, W.H.; Wang, X.H.; Chen, A.Q. Magnetically Tunable Terahertz Isolator Based on Structured Semiconductor Magneto Plasmonics. IEEE Photon Technol Lett 2012, 24, 2080–2083. [Google Scholar]

- Jablan, M.; Buljan, H.; Soljačić, M. Plasmonics in graphene at infrared frequencies. Phys Rev B 2009, 80, 245435. [Google Scholar]

- Grigorenko, A. N.; Polini, M.; Novoselov, K.S. Graphene plasmonics. Nat Photon 2012, 6, 749–758. [Google Scholar]

- Low, T.; Avouris, P. Graphene Plasmonics for Terahertz to Mid-Infrared Applications. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 1086–1101. [Google Scholar]

- García de Abajo, F.J. Graphene Plasmonics: Challenges and Opportunities. ACS Photon 2014, 1, 135–152. [Google Scholar]

- Pimenov, A.; Shuvaev, A.; Loidl, A.; Schrettle, F.; Mukhin, A.A.; Travkin, V.D.; Ivanov, V.Y.; Balbashov, A.M. Magnetic and Magnetoelectric Excitations in TbMnO3. Phys Rev Lett 2009, 102, 107203. [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima, M.; Namai, A.; Ohkoshi, S.; Suemoto, T. Ultrafast time domain demonstration of bulk magnetization precession at zero magnetic field ferromagnetic resonance induced by terahertz magnetic field. Opt Express 2010, 18, 18260–18268. [Google Scholar]

- Kampfrath, T.; Sell, A.; Klatt, G.; Pashkin, A.; Mährlein, S.; Dekorsy, T.; Wolf, M.; Fiebig, M.; Leitenstorfer, A.; Huber, R. Coherent terahertz control of antiferromagnetic spin waves. Nat Photon 2011, 5, 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, K.; Kurihara, T.; Minami, Y.; Nakajima, M.; Suemoto, T. Terahertz Time-Domain Observation of Spin Reorientation in Orthoferrite ErFeO3 through Magnetic Free Induction Decay. Phys Rev Lett 2013, 110, 137204. [Google Scholar]

- Wienholdt, S.; Hinzke, D.; Nowak, U. THz Switching of Antiferromagnets and Ferrimagnets. Phys Rev Lett 2012, 108, 247207. [Google Scholar]

- Constable, E.; Cortie, D.L.; Horvat, J.; Lewis, R.A.; Cheng, Z.; Deng, G.; Cao, S.; Yuan, S.; Ma, G. Complementary terahertz absorption and inelastic neutron study of the dynamic anisotropy contribution to zone-center spin waves in a canted antiferromagnet NdFeO3. Phys Rev B 2014, 90, 054413. [Google Scholar]

- Kurihara, T.; Nakamura, K.; Yamaguchi, K.; Sekine, Y.; Saito, Y.; Nakajima, M.; Oto, K.; Watanabe, H.; Suemoto, T. Enhanced spin-precession dynamics in a spin-metamaterial coupled resonator observed in terahertz time-domain measurements. Phys Rev B 2014, 90, 144408. [Google Scholar]

- Davoyan, A.R.; Engheta, N. Nonreciprocal Rotating Power Flow within Plasmonic Nanostructures. Phys Rev Lett 2013, 111, 047401. [Google Scholar]

- Davoyan, A.R.; Engheta, N. Theory of Wave Propagation in Magnetized Near-Zero-Epsilon Metamaterials: Evidence for One-Way Photonic States and Magnetically Switched Transparency and Opacity. Phys Rev Lett 2013, 111, 257401. [Google Scholar]

- Chettiar, U.K.; Davoyan, A.R.; Engheta, N. Hotspots from nonreciprocal surface waves. Opt Lett 2014, 39, 1760–1763. [Google Scholar]

- Hadad, Y.; Steinberg, B.Z. Magnetized Spiral Chains of Plasmonic Ellipsoids for One-Way Optical Waveguides. Phys Rev Lett 2010, 105, 233904. [Google Scholar]

- Hadad, Y.; Steinberg, B.Z. One way optical waveguides for matched non-reciprocal nanoantennas with dynamic beam scanning functionality. Opt Express 2013, 21, A77–A83. [Google Scholar]

- Mazor, Y.; Steinberg, B.Z. Longitudinal chirality, enhanced nonreciprocity, and nanoscale planar one-way plasmonic guiding. Phys Rev B 2012, 86, 045120. [Google Scholar]

- Mazor, Y.; Steinberg, B.Z. Metaweaves: Sector-Way Nonreciprocal Metasurfaces. Phys Rev Lett 2014, 112, 153901. [Google Scholar]

- Hadad, Y.; Mazor, Y.; Steinberg, B.Z. Green’s function theory for one-way particle chains. Phys Rev B 2013, 87, 035130. [Google Scholar]

- Lozovik, Y.E. Plasmonics and magnetoplasmonics based on graphene and a topological insulator. Phys Usp 2012, 55, 1035. [Google Scholar]

- Crassee, I.; Orlita, M.; Potemski, M.; Walter, A.L.; Ostler, M.; Seyller, T.; Gaponenko, I.; Chen, J.; Kuzmenko, A.B. Intrinsic Terahertz Plasmons and Magnetoplasmons in Large Scale Monolayer Graphene. Nano Lett 2012, 12, 2470–2474. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, A.; Peres, N.M.R.; Castro Neto, A.H. Confined magneto-optical waves in graphene. Phys Rev B 2012, 85, 205426. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Zhu, W.; Avouris, P.; Xia, F. Infrared Spectroscopy of Tunable Dirac Terahertz Magneto-Plasmons in Graphene. Nano Lett 2012, 12, 3766–3771. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Xu, X.; Fan, H.; Ren, Z.; Bai, J.; Wang, L. Tunable magnetoplasmons for efficient terahertz modulator and isolator by gated monolayer graphene. Phys Chem Chem Phys 2013, 15, 5084–5090. [Google Scholar]

- Chamanara, N.; Caloz, C. Tunable Terahertz Graphene Magnetoplasmons: Non-Reciprocal Components and Applications. Proceedings of the 2014 8th European Conference on Antennas and Propagation (EuCAP), Hague, The Netherlands, 6–11 April 2014; pp. 670–671.

- Hu, B.; Tao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.J. Magneto-plasmonics in graphene-dielectric sandwich. Opt Express 2014, 22, 21727–21738. [Google Scholar]

- Hadad, Y.; Davoyan, A.R.; Engheta, N.; Steinberg, B.Z. Extreme and Quantized Magneto-Optics with Graphene Meta-Atoms and Metasurfaces. ACS Photon 2014, 1, 1068–1073. [Google Scholar]

- Ebbesen, T.W.; Lezec, H.J.; Ghaemi, H.F.; Thio, T.; Wolff, P.A. Extraordinary optical transmission through sub-wavelength hole arrays. Nature 1998, 391, 667–669. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman, D.J.; Strelniker, Y.M. Anisotropic ac Electrical Permittivity of a Periodic Metal-Dielectric Composite Film in a Strong Magnetic Field. Phys Rev Lett 1998, 80, 857–860. [Google Scholar]

- Strelniker, Y.M.; Bergman, D.J. Optical transmission through metal films with a subwavelength hole array in the presence of a magnetic field. Phys Rev B 1999, 59, R12763–R12766. [Google Scholar]

- Strelniker, Y.M.; Bergman, D.J. Transmittance and transparency of subwavelength-perforated conducting films in the presence of a magnetic field. Phys Rev B 2008, 77, 205113. [Google Scholar]

- Strelniker, Y.M.; Bergman, D.J. Strong angular magneto-induced anisotropy of Voigt effect in metal-dielectric metamaterials with periodic nanostructures. Phys Rev B 2014, 89, 125312. [Google Scholar]

- Battula, A.; Chen, S.; Lu, Y.; Knize, R.J.; Reinhardt, K. Tuning the extraordinary optical transmission through subwavelength hole array by applying a magnetic field. Opt Lett 2007, 32, 2692–2694. [Google Scholar]

- García-Martín, A.; Armelles, G.; Pereira, S. Light transport in photonic crystals composed of magneto-optically active materials. Phys Rev B 2005, 71, 205116. [Google Scholar]

- Helseth, L.E. Tunable plasma response of a metal/ferromagnetic composite material. Phys Rev B 2005, 72, 033409. [Google Scholar]

- Khanikaev, A.B.; Baryshev, A.V.; Fedyanin, A.A.; Granovsky, A.B.; Inoue, M. Anomalous Faraday effect of a system with extraordinary optical transmittance. Opt Express 2007, 15, 6612–6622. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, R.; Li, H.; Zhou, B.; Wu, L.; Liu, X.; Gao, Y. Transmission through a perforated metal film by applying an external magnetic field. Solid State Commun 2009, 149, 657–661. [Google Scholar]

- Ou, N.; Shyu, J.; Wu, J.; Wu, T. Extraordinary Optical Transmission Through Dielectric Hole-Array Coated With TbFeCo Thin Film. IEEE Trans Magnet 2009, 45, 4027–4029. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman, D.J.; Stockman, M.I. Surface Plasmon Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation: Quantum Generation of Coherent Surface Plasmons in Nanosystems. Phys Rev Lett 2003, 90, 027402. [Google Scholar]

- Baranov, D.G.; Vinogradov, A.P.; Lisyansky, A.A.; Strelniker, Y.M.; Bergman, D.J. Magneto-optical spaser. Opt Lett 2013, 38, 2002–2004. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.W.; Solanki, S.; Liang, X.A.; Pan, Y.C.; Chong, T.C. Full high-definition digital 3D holographic display and its enabling technologies. Proc SPIE 2010, 7730, 77301C. [Google Scholar]

- Butykai, A.; Orbán, A.; Kocsis, V.; Szaller, D.; Bordács, S.; Tátrai-Szekeres, E.; Bóta, A.; L.F.K.; Vértessy, B.G.; Zelles, T.; Kézsmárki, I. Malaria pigment crystals as magnetic micro-rotors: key for high-sensitivity diagnosis. Sci Rep 2013, 3, 1431. [Google Scholar]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Maksymov, I.S. Magneto-Plasmonics and Resonant Interaction of Light with Dynamic Magnetisation in Metallic and All-Magneto-Dielectric Nanostructures. Nanomaterials 2015, 5, 577-613. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano5020577

Maksymov IS. Magneto-Plasmonics and Resonant Interaction of Light with Dynamic Magnetisation in Metallic and All-Magneto-Dielectric Nanostructures. Nanomaterials. 2015; 5(2):577-613. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano5020577

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaksymov, Ivan S. 2015. "Magneto-Plasmonics and Resonant Interaction of Light with Dynamic Magnetisation in Metallic and All-Magneto-Dielectric Nanostructures" Nanomaterials 5, no. 2: 577-613. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano5020577