Framing Islam/Creating Fear: An Analysis of U.S. Media Coverage of Terrorism from 2011–2016

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Terrorism and Media

Terrorism is an anxiety inspiring method of repeated violent action, employed by (semi-) clandestine individual, group or state actors, for idiosyncratic, criminal or political reasons, whereby—in contrast to assassination—the direct targets of violence are not the main targets. The immediate human victims of violence are generally chosen randomly (targets of opportunity) or selectively (representative of symbolic targets) from a target population, and serve as message generators. Threat- and violence-based communication processes between terrorist (organization), (imperiled) victims, and main targets are used to manipulate the main target (audience(s)), turning it into a target of terror, a target of demands, or a target of attention depending on whether intimidation, coercion, or propaganda is primarily sought.

Experts—and the dictionary—define terrorism as the use of violence and fear to pursue political goals …. President Barack Obama didn’t use the word when he spoke hours after the attack. By Tuesday, he called it an “act of terror” any time bombs are used to target innocent civilians … some history students at Kent Place School in New Jersey … want more information before deciding what to call the Boston tragedy.

3. Method

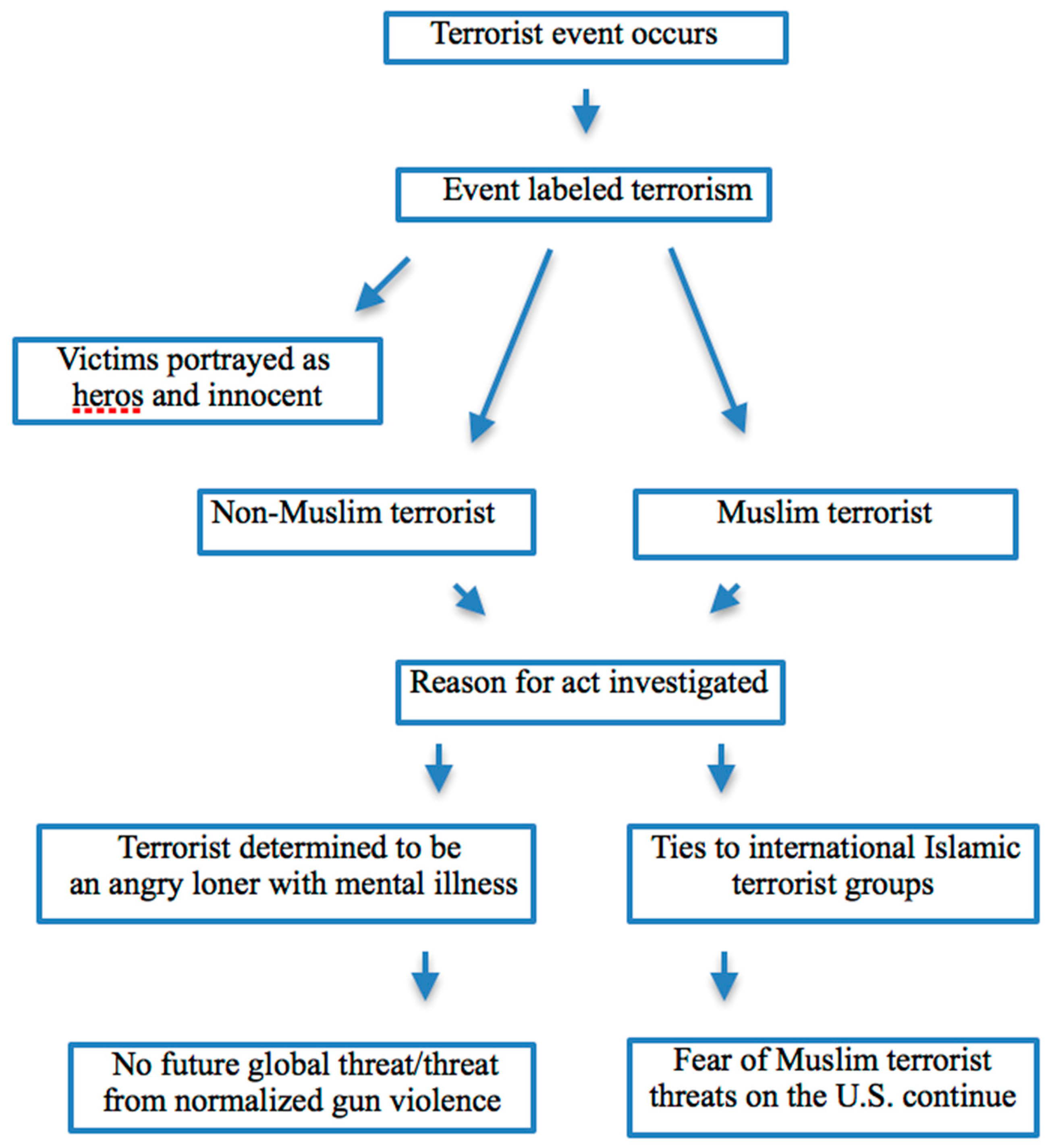

4. Framing Analysis

5. Description of the Agent

5.1. Domestic Agents

5.2. International Agent

6. Motive for Act

7. Victim as Good/Terrorist as Evil

7.1. Hero

7.2. Good and Innocent

7.3. Terrorist as Evil

8. Tool Used/Gun Control Debate

9. Discussion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, Saeed, Ed Lavandara, and Catherine E. Shoichet. 2014. Alleged Kansas Jewish Center Gunman Charged with Murder. CNN. April 15. Available online: http://www.cnn.com/2014/04/15/us/kansas-jewish-center-shooting/index.html (accessed on 16 November 2016).

- Alvarez, Lizette, and Alan Blinder. 2015. Recalling nine spiritual mentors, gunned down during night of devotion. The New York Times. June 18. Available online: http://search.proquest.com/usnews/docview/1689794150/30E34852CD124828PQ/34?accountid=27921 (accessed on 10 February 2017).

- Associated Press. 2013a. 2 Dead, More than 130 Injured as 2 Bombs Explode near Boston Marathon Finish Line. Fox News. April 15. Available online: http://www.foxnews.com/us/2013/04/15/3-dead-more-than-130-injured-as-2-bombs-explode-near-boston-marathon-finish.html (accessed on 3 March 2017).

- Associated Press. 2013b. What Is ‘Terrorism’? Boston Bombings Renew Efforts to Define Pain, Motives in a Single Word. Fox News. April 18. Available online: http://www.foxnews.com/us/2013/04/18/what-is-terrorism-boston-bombings-renew-efforts-to-define-pain-motives-in.html (accessed on 17 November 2016).

- Associated Press. 2013c. Los Angeles Airport Shooting Suspect Had Sent Suicidal Text to Sibling, NJ Police Chief Says. Fox News. November 2. Available online: http://www.foxnews.com/us/2013/11/02/los-angeles-airport-shooting-suspect-had-sent-suicidal-text-to-sibling-nj.html (accessed on 16 July 2017).

- Bail, Christopher A. 2012. The Fringe Effect: Civil Society Organizations and the Evolution of Media Discourse about Islam since the September 11th Attacks. American Sociological Review 77: 855–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, Jesse. 2015. Charleston Massacre Suspect’s Uncle: “I Hope He Gets What’s Coming to Him”. MSNBC. June 18. Available online: http://www.msnbc.com/hardball/charleston-massacre-suspects-uncle-i-hope-he-gets-whats-coming-him (accessed on 16 July 2017).

- Borden, Jeremy, Sari Horowitz, and Jerry Markon. 2015. From Victims’ Families, Forgiveness for Accused Charleston Gunman Dylann Roof. The Washington Post. June 19. Available online: http://search.proquest.com/usnews/docview/1689974007/763706A7ECA9457BPQ/12?accountid=27921 (accessed on 18 July 2017).

- Botelho, Greg, Ralph Ellis, and Victor Blackwell. 2015. 4 Guns Seized after Chattanooga Shooting, Official Says. CNN. July 17. Available online: http://www.cnn.com/2015/07/17/us/tennessee-naval-reserve-shooting/index.html (accessed on 17 July 2017).

- Bowe, Brian J., and Taj W. Makki. 2016. Muslim neighbors or an Islamic threat? A constructionist framing analysis of newspaper coverage of mosque controversies. Media, Culture & Society 38: 540–58. [Google Scholar]

- Brumfield, Ben, and Scott Zamost. 2015. Chattanooga Shooter Changed after Mideast Visit, Friend Says. CNN. July 17. Available online: http://www.cnn.com/2015/07/17/us/tennessee-shooter-mohammad-youssuf-abdulazeez/index.html (accessed on 17 November 2017).

- Brummett, Barry. 1994. Rhetoric in Popular Culture. New York: St. Martin’s Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chesebro, James W., and Dale A. Bertelsen. 1996. Analyzing Media: Communication Technologies as Symbolic and Cognitive Systems. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chivers, Christopher John. 2016. Man Used Assault Rifle with Military Roots. New York Times. June 13. Available online: http://proxy.luther.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com.proxy.luther.edu/docview/1795815802?accountid=27921 (accessed on 5 July 2016).

- Costa, Robert. 2015. Shaken Charleston Mayor: ‘Far Too Many Guns out There’. The Washington Post. Available online: http://search.proquest.com/usnews/docview/1689968133/763706A7ECA9457BPQ/23?accountid=27921 (accessed on 7 July 2018).

- Diebel, Matthew. 2015. Slain Rev. Pinckney Described as ‘a Giant’. USA Today. June 18. Available online: http://search.proquest.com/usnews/docview/1689884054/5A195E1505224D48PQ/15?accountid=27921 (accessed on 13 November 2016).

- Entman, Robert M. 1989. Democracy without Citizens: Media and the Decay of American Politics. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Entman, Robert M. 1993. Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication 43: 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, Robert M., and Andrew Rojecki. 1993. Freezing out the public: Elite and media framing of the US anti-nuclear movement. Political Communication 10: 151–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fausset, Richard, Blinder, and Michael Schmidt. 2015. Gunman Kills 4 at Military Site in Chattanooga. The New York Times. July 16. Available online: http://search.proquest.com/usnews/docview/1696831931/A27F6589F99048D5PQ/1?accountid=27921 (accessed on 7 July 2018).

- Fernandez, Manny, Alan Blinder, Eric Schmitt, and Richard Perez-Pena. 2015a. In Chattanooga, Young Man in Downward Spiral. The New York Times. July 20. Available online: http://search.proquest.com/usnews/docview/1697379481/A27F6589F99048D5PQ/9?accountid=27921 (accessed on 16 November 2016).

- Fernandez, Manny, Richard Perez-Pena, and Juan Santos. 2015b. Gunman in Texas Shooting Was F.B.I. Suspect in Jihad Inquiry. The New York Times. May 4. Available online: http://search.proquest.com/usnews/docview/1712371966/67B342B312A448FDPQ/1?accountid=27921 (accessed on 13 November 2016).

- Fieldstadt, Elisha. 2015. Victims of Planned Parenthood Shooting Identified as Mother of Two, Army Veteran. MSNBC. November 29. Available online: http://www.msnbc.com/msnbc/victims-planned-parenthood-shooting-identified-mother-two-army-veteran (accessed on 7 July 2017).

- Fisher, Marc. 2013. Knowledge of Pressure-Cooker Bombs Is Not Limited to Readers of Al-Qaeda’s ‘Inspire’ Magazine. The Washington Post. April 16. Available online: http://search.proquest.com.proxy.luther.edu/usnews/docview/1327617658/3556A25991974C84PQ/126?accountid=27921 (accessed on 6 July 2018).

- Fitzsimmons, Emma G. 2014. Man Kills 3 at Jewish Centers in Kansas City Suburb. The New York Times. April 13. Available online: http://search.proquest.com/usnews/docview/1515621422/5BC4AE39331046CEPQ/1?accountid=27921 (accessed on 3 July 2016).

- Gitlin, Todd. 1980. The Whole World Is Watching: Mass Media in the Making & Unmaking of the New Left. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, Erving. 1974. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. New York: Harper & Row, pp. 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Gun Laws. 2015. Gun Laws and the San Bernardino Shooting (Posted 2015-12-08 23:00:18). The Washington Post. December 8. Available online: http://proxy.luther.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com.proxy.luther.edu/docview/1746801671?accountid=27921 (accessed on 16 July 2017).

- Hauser, Christine. 2015. San Bernardino Shooting: The Investigation So Far. The New York Times. December 4. Available online: http://search.proquest.com.proxy.luther.edu/docview/1739286825/1DFF9FAEC3B547CDPQ/12?accountid=27921 (accessed on 18 July 2016).

- Horwitz, Sari. 2015. Guns Used in San Bernardino Shooting Were Purchased Legally from Dealers (posted 2015-12-03 18:50:39). The Washington Post. December 3. Available online: http://proxy.luther.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com.proxy.luther.edu/docview/1739002272?accountid=27921 (accessed on 16 July 2016).

- Hughes, T. 2015. Planned Parenthood suspect in court. USA Today. November 30. Available online: http://web.a.ebscohost.com.proxy.luther.edu/ehost/detail/detail?sid=153b075d-70c8-4e3d-b290-5b6cc8d1d20d%40sessionmgr4005&vid=0&hid=4209&bdata=JnNjb3BlPXNpdGU%3d#AN=J0E188122714415&db=a9h (accessed on 27 August 2016).

- Huntington, Samuel P. 1993. The clash of civilizations? Foreign Affairs 72: 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, Shanto, and Adam Simon. 1993. News coverage of the Gulf crisis and public opinion: A study of agenda-setting, priming, and framing. Communication Research 20: 365–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, Kathleen Hall, and Paul Waldman. 2003. The Press Effect: Politicians, Journalists and the Stories that Shape the Political World. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jervis, Rick. 2015. Hate in America: Study of Violence Spots Rise in ‘Lone Wolf’ Attacks. USA Today. June 19. Available online: http://search.proquest.com/usnews/docview/1689883957/5A195E1505224D48PQ/13?accountid=27921 (accessed on 13 November 2016).

- Karimi, Faith. 2015. San Bernardino Shooting: Who Were the Victims? CNN. December 3. Available online: http://www.cnn.com/2015/12/03/us/san-bernardino-shootings-victims/index.html (accessed on 16 November 2016).

- Kube, Courtney. 2015. Chattanooga Shooting: Marines ID Victims, Including Recipient of Purple Heart. MSNBC. July 17. Available online: http://www.msnbc.com/msnbc/chattanooga-shooting-marines-id-victims-including-recipient-purple-heart (accessed on 18 July 2016).

- Khan, Rahim F., Zafar Iqbal, Osman Gazzaz, and Sadollah Ahrari. 2012. Global media image of Islam and Muslims and the problematics of a response strategy. Islamic studies 51: 5–25. [Google Scholar]

- Landler, Mark. 2013. A Setback Met by Anger, Another by Resolve. New York Times. April 18. Available online: http://search.proquest.com/usnews/docview/1328446942/fulltext/5C26485E56744E4DPQ/38?accountid=27921 (accessed on 15 July 2016).

- Markham, James W., and Crispin Maslog. 1971. Images and the mass media. The Journalism Quarterly 48: 519–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Jonathan. 2015. Obama Says ‘Enough Is Enough’ after Colorado Shooting. New York Times. November 29. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/29/us/colorado-springs-planned-parenthood-obama-responds-to-gun-violence.html (accessed on 1 August 2016).

- McFarland, Kathleen Troia. 2015. After San Bernardino: How Political Correctness Could Get Us All Killed. Fox News. December 4. Available online: http://www.foxnews.com/opinion/2015/12/04/after-san-bernardino-how-political-correctness-could-get-us-all-killed.html (accessed on 5 July 2016).

- McIntire, Mike. 2015. Weapons in San Bernardino Shootings Were Legally Obtained. New York Times. December 3. Available online: http://search.proquest.com.proxy.luther.edu/docview/1738904731/1DFF9FAEC3B547CDPQ/7?accountid=27921 (accessed on 7 July 2017).

- Medina, Jennifer, and Ian Lovett. 2013. 2 Lives Collide in Fatal Instant at Busy Airport. New York Times. November 2. Available online: http://search.proquest.com/usnews/docview/1447993527/fulltext/E76071BC11504B66PQ/2?accountid=27921 (accessed on 9 July 2017).

- Medina, Jennifer, Richard Perez-Pena, Michael S. Schmidt, and Laurie Goodstein. 2015. San Bernardino Suspects Left Trail of Clues, But No Clear Motive. Available online: http://search.proquest.com.proxy.luther.edudocview1738904701/1DFF9FAEC3B547CDPQ/4?accountid=27921 (accessed on 11 July 2017).

- Miller, Judith. 2013. A Desire to Be Part of an ‘Epic Struggle’—A New Profile of Jihadists. Fox News. April 18. Available online: http://www.foxnews.com/opinion/2013/04/18/stray-dogs-not-lone-wolves-new-profile-jihadis.html (accessed on 14 July 2016).

- Fox News. 2016. Orlando shooting revives a fight over ‘Islamic’ label. Fox News. June 13. Available online: http://www.foxnews.com/us/2016/06/13/orlando-shooting-revives-fight-over-islamic-label.html (accessed on 13 June 2016).

- Nagourney, Adam, lan Lovett, and Richard Perez-Pena. 2015a. San Bernardino Shooting Kills at Least 14; Two Suspects Are Dead. Available online: http://search.proquest.com.proxy.luther.edu/docview/1738828313/1DFF9FAEC3B547CDPQ/21?accountid=27921 (accessed on 19 July 2016).

- Nagourney, Adam, Salman Masood, and Michael S. Schmidt. 2015b. Killers Were Long Radicalized, F.B.I. Investigators Say. Available online: http://search.proquest.com.proxy.luther.edu/docview/1744903863/1DFF9FAEC3B547CDPQ/47?accountid=27921 (accessed on 23 July 2016).

- Norris, Pippa, Montague Kern, and Marion Just. 2003. Framing Terrorism. New York: Routledge Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, Bill. 2015. More Americans Die at the Hands of Muslim Extremists. Fox News. December 4. Available online: http://www.foxnews.com/transcript/2015/12/04/bill-oreilly-more-americans-die-at-hands-Muslim-extremists/ (accessed on 2 July 2016).

- Ohlheiser, Abby, and Elahe Izadi. 2014. Police: Austin Shooter Was a ‘Homegrown American Extremist’. The Washington Post. December 1. Available online: http://search.proquest.com/usnews/docview/1629483461/1859B074198E410DPQ/2?accountid=27921 (accessed on 6 July 2016).

- Parker, Kim. 2014. Armed and Dead. The Washington Post. June 10. Available online: http://search.proquest.com/usnews/docview/1534422698/CCA0AB3EAA774D73PQ/6?accountid=27921 (accessed on 9 July 2016).

- Powell, Kimberly A. 2011. Framing Islam: An analysis of media coverage of terrorism since 9/11. Communication Studies 62: 90–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, Kimberly A., and Houda Abadi. 2003. Us-versus-them: Framing of Islam and Muslims after 9/11. Iowa Journal of Communication 35: 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Reese, Stephen D. 2001. Framing public life: A bridging model for media research. In Framing Public Life. Edited by Stephen D. Reese, Oscar H. Gandy Jr. and August E. Grant. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 7–31. [Google Scholar]

- Reese, Stephen D., and Seth C. Lewis. 2009. Framing the war on terror: The internalization of policy in the US Press. Journalism 10: 777–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, Frances, Jason Horowitz, and Shaila Dewan. 2015. Flying the Flags of White Power. The New York Times. June 19. Available online: http://search.proquest.com/usnews/docview/1689794886/30E34852CD124828PQ/33?accountid=27921 (accessed on 10 July 2016).

- Russian Media. 2013. Russian Media Reports on Boston Bombing Suspects’ Online Activity. Fox News. April 19. Available online: http://www.foxnews.com/world/2013/04/19/russian-media-reports-on-boston-bombing-suspects-online-activity.html (accessed on 11 July 2016).

- Ryan, Charlotte. 1991. Prime Time Activism: Media Strategies for Grassroots Organizing. Boston: South End Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, Missy, Adam Goldman, and Almond Phillip. 2015. San Bernardino Shooters Had Been Radicalized for ‘Some Time,’ FBI Says (Posted 2015-12-08 01:50:14). The Washington Post. Available online: http://proxy.luther.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com.proxy.luther.edu/docview/1744907609?accountid=27921 (accessed on 10 July 2016).

- Said, Edward. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- Saleem, Muniba, Sara Prot, Craig A. Anderson, and Anthony F. Lemieux. 2017. Exposure to Muslims in Media and Support for Public Policies Harming Muslims. Communication Research 44: 841–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, Alex P. 1983. Political Terrorism: A Research Guide to Concepts, Theories, Data Bases and Literature. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Schuppe, Jon. 2015. San Bernardino shooter Tashfeen Malik’s Father Condemns Attack. MSNBC. December 9. Available online: http://www.msnbc.com/msnbc/san-bernardino-shooter-tashfeen-malik-father-condemns-attack (accessed on 15 July 2016).

- Semati, Mehdi. 2010. Islamophobia, culture, and race in the age of empire. Cultural Studies 24: 256–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Hemant, and Michael C. Thornton. 1994. Racial ideology in US mainstream news magazine coverage of black-latino interaction, 1980–1992. Critical Studies in Mass Communication 40: 141–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, Saif. 2015. News Framing as Identity Performance: Religion versus Race in the American-Muslim Press. Journal of Communication Inquiry 39: 338–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shook, Fred. 2000. Television Field Production and Reporting. Boston: Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Solis, Steph, and Alison Young. 2016. Orlando Nightclub Shooting: What We Know. USA Today. June 12. Available online: http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2016/06/12/orlando-nightclub-shooting-what-we-know/85786006/ (accessed on 16 July 2016).

- Tuman, Joseph S. 2010. Communicating Terror: The Rhetorical Dimensions of Terrorism. New York: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Victor, Daniel, and Jack Healy. 2015. Garrett Swasey, Officer Killed in Colorado, Is Recalled for Courage and Faith. The New York Times. November 11. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/28/us/garrett-swasey-officer-killed-in-colorado-is-recalled-for-courage-and-faith.html?mtrref=query.nytimes.com (accessed on 16 July 2016).

- Wagner, James. 2013. Jayson Werth on Boston Marathon: Sporting Event Being Targeted Is ‘a Scary Thought’. The Washington Post. April 17. Available online: http://search.proquest.com.proxy.luther.edu/docview/1327617874/D4419F9C03DC445CPQ/50?accountid=27921 (accessed on 5 July 2016).

- Wan, William. 2015. Colo. Shooting Suspect Has Long Trail of Abuse Allegations. Washington Post. December 1. Available online: http://search.proquest.com/usnews/docview/1738242902/72F1774085AC43B4PQ/34?accountid=27921 (accessed on 6 August 2016).

- Yan, Holly. 2015. ISIS Claims Responsibility for Texas Shooting But Offers no Proof. CNN. May 5. Available online: http://www.cnn.com/2015/05/05/us/garland-texas-prophet-mohammed-contest-shooting/index.html (accessed on 5 August 2016).

- Zamost, Scott, Yasmin Khorram, Shimon Prokupecz, and Evan Perez. 2015. Chattanooga Shooting: New Details Emerge about the Gunman. CNN. July 20. Available online: http://www.cnn.com/2015/07/20/us/tennessee-naval-reserve-shooting/index.html (accessed on 20 July 2016).

- Zimmerman, Malia. 2015. Tennessee Gunman First Radicalized, Now Idolized by Internet Jihadists. Fox News. July 18. Available online: http://www.foxnews.com/us/2015/07/18/tennessee-gunman-first-radicalized-now-idolized-by-internet-jihadists.html (accessed on 25 July 2016).

| Date | Who Committed the Act | Description of Event |

|---|---|---|

| April 2013 | Tamerian Tsarnaev & Dzhokar Tsarnaev | Bombing at the Boston Marathon killed 4 and injured over 180 |

| November 2013 | Paul Anthony Ciancia | Shooting at LA International Airport. One killed, 6 injured. |

| April 2014 | Frazier Glenn Miller, Jr. | Shooting at Overland Park Jewish Community Center killed 3 |

| June 2014 | Jerad and Amanda Miller | Shooting in Las Vegas killed 3 |

| November 2014 | Larry Steven McQuilliams | Shooting in Austin, TX only gunman killed |

| May 2015 | Elton Simpson & Nadir Soofi | Shooting at the Curtis Curtwell Center in Garland, TX injuries, no deaths |

| June 2015 | Dylann Roof | Shooting at the SC Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, SC. Killed 9, injured 1 |

| November 2015 | Robert L. Dear | Shooting at Colorado Springs Planned Parenthood killing 3, injuring 9 |

| December 2015 | Rizwan Farook & Tashfeen Malik | Shooting in San Bernadino, CA 14 killed, 22 injured |

| June 2016 | Omar Mateen | Shooting in Orlando, FL 49 killed, 53 injured |

| July 2016 | Muhammad Youssef Abdulazeez | Shooting at the Chattanooga, TN Military Installation killing 5, injuring 2 |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Powell, K.A. Framing Islam/Creating Fear: An Analysis of U.S. Media Coverage of Terrorism from 2011–2016. Religions 2018, 9, 257. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9090257

Powell KA. Framing Islam/Creating Fear: An Analysis of U.S. Media Coverage of Terrorism from 2011–2016. Religions. 2018; 9(9):257. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9090257

Chicago/Turabian StylePowell, Kimberly A. 2018. "Framing Islam/Creating Fear: An Analysis of U.S. Media Coverage of Terrorism from 2011–2016" Religions 9, no. 9: 257. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9090257