The Ritualizing of the Martial and Benevolent Side of Ravana in Two Annual Rituals at the Sri Devram Maha Viharaya in Pannipitiya, Sri Lanka

Abstract

:1. Introduction

දඬු මොනරෙන් වඩිනා දෙවියෝමහා ඇතුපිට වඩිනා දෙවියෝසිවු රඟ සේනා ඇති දෙවියෝවඩිනු මැනිවි රාවණ දෙවියෝ

1 The god who arrives on the dandu monaraThe god who arrives on the great tuskerThe god who owns the fourfold armiesMay god Ravana arrive

හිස් දහයක් ඇති මහ දෙවියෝඅත් විස්සක් ඇති මහ දෙවියෝදය බලයක් ඇති මහ දෙවියෝවඩිනු මැනිවි රාවණ දෙවියෝ

2 The great god with ten headsThe great god with twenty armsThe great god with ten powersMay god Ravana arrive

වෙද දුරු මහ රජ මහ දෙවියෝකෙත් වතු සරු කළ මහ දෙවියෝහිරැ එළියෙන් වෙඩගත් දෙවියෝවඩිනු මැනිවි රාවණ දෙවියෝ

3 The great god who’s a doctor and a great kingThe great god who brought prosperity to paddy fieldsThe great god who received favors from the light of the sunMay god Ravana arrive

මුළු ලොව ජයගත් මහ දෙවියෝහෙළයට පණ දුන් මහ දෙවියෝතුන් ලොව පුජිත මහ දෙවියෝවඩිනු මැනිවි රාවණ දෙවියෝ

6 The great god who won the whole worldThe great god who gave life to the land of HelaThe great god worshipped by the threefold worldsMay god Ravana arrive

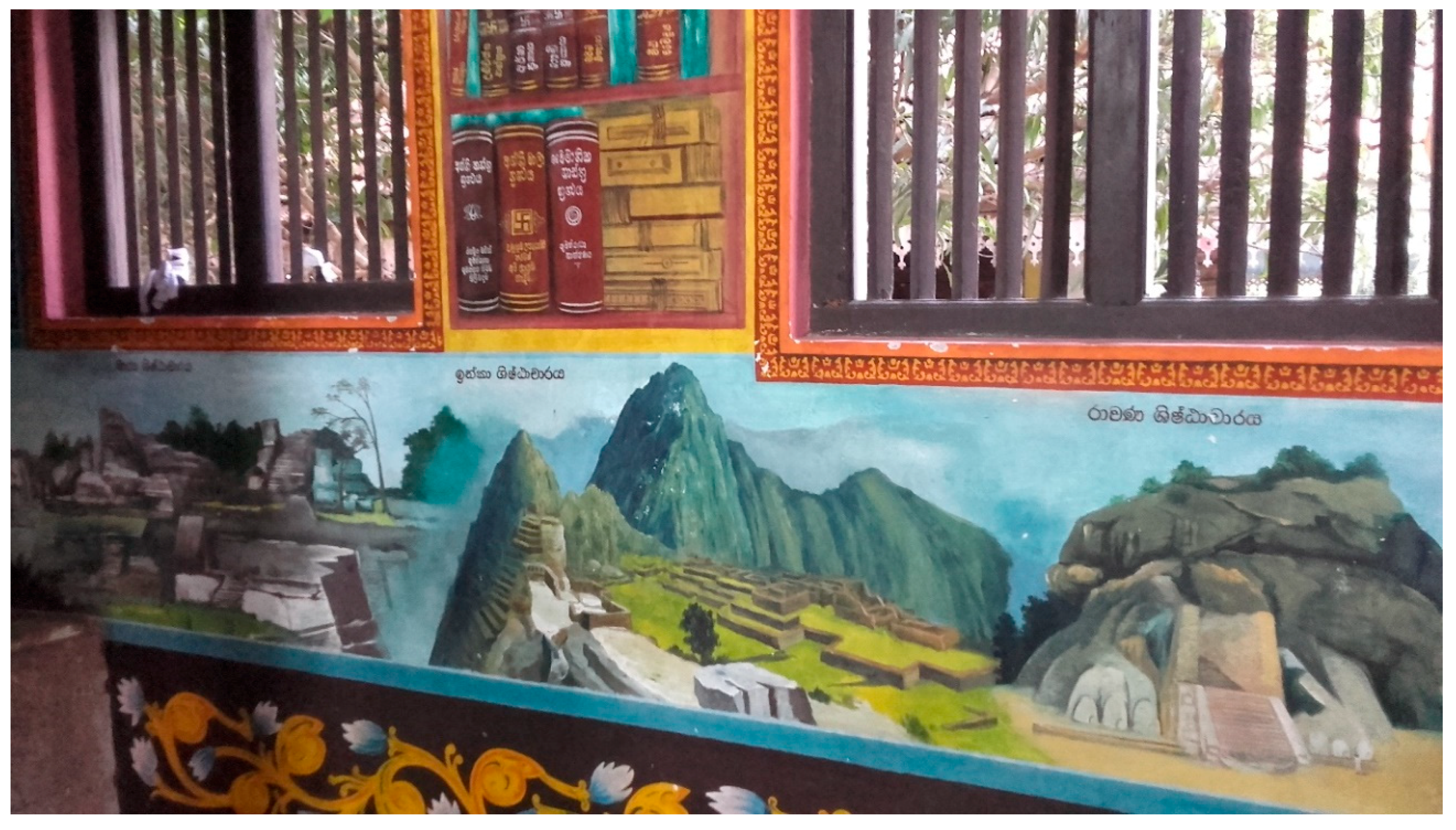

2. The Sri Devram Maha Viharaya

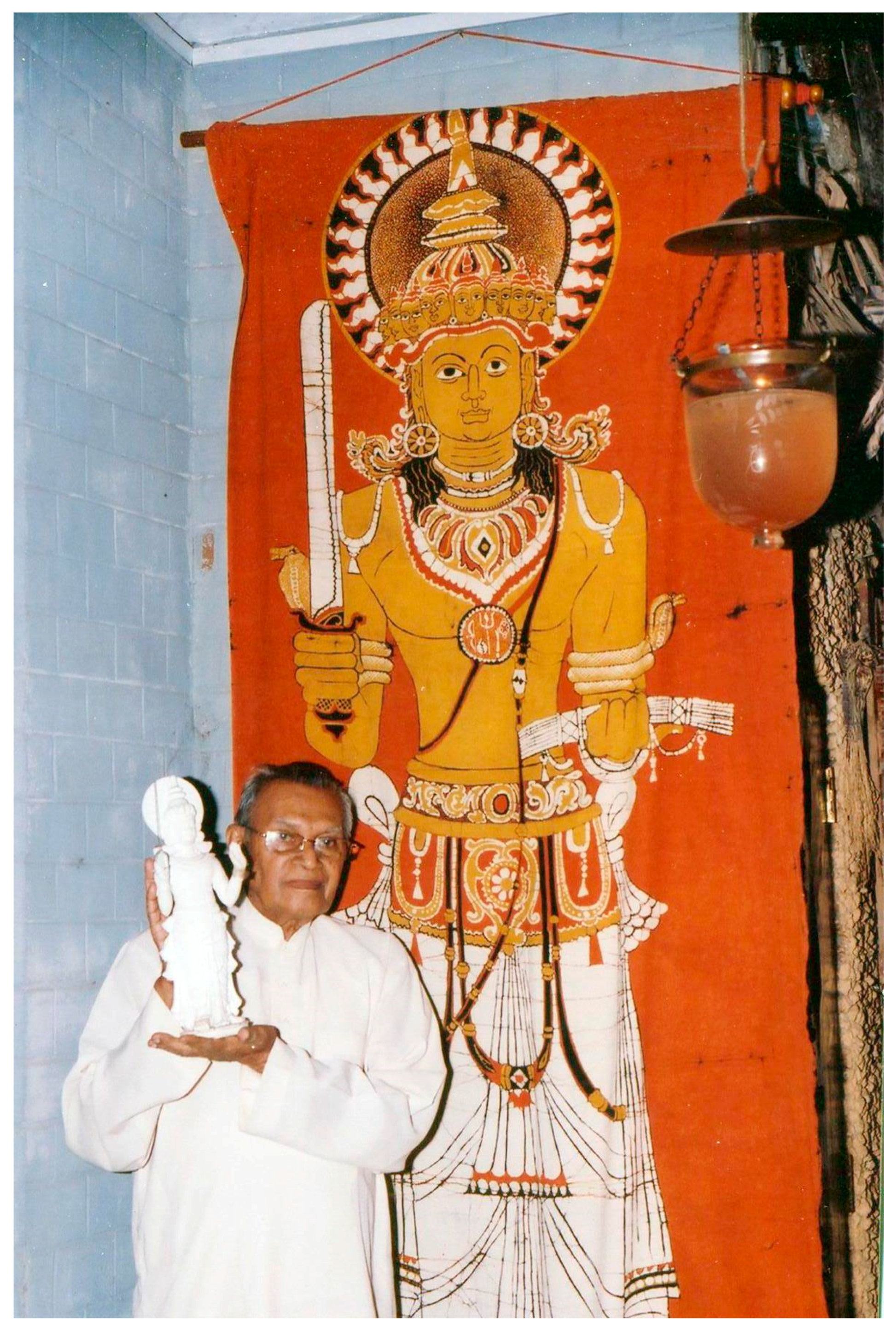

3. The Sword and Scripture of Ravana

[…] It is the ola leaf book and the sword. The sword signifies his power and bravery and that there is nothing he cannot do. The ola leaf book signifies his wisdom or intelligence. […] In the present day why we have given the statue a sword is because there is a lot of injustice, crime and lack of peace around the world. We believe that these problems should be solved and that king Ravana has the power to solve them. [The book symbolizes] knowledge about peace, justice and ruling, as well as universal knowledge about war and medication. Since the brain cannot be given to the hand, we have signified his great wisdom using this book.

4. The Ritualizing of Ravana as a Warrior King in the Annual Maha Ravana Perahera

[The Ravana perahera] is dedicated towards all the kings of ancient Sri Lanka who sacrificed not just their time, but also their lives towards protecting and bringing prosperity to the nation and its people. The statue of king Ravana is taken as a representation of all the kings of the country due to the great wisdom and holiness with which king Ravana ruled not just Sri Lanka but the entire universe. He is considered the greatest among the kings in the country […].

It [the rana bera] was used in fight and battle and it symbolized strength. When going to war, the rana bera announced the arrival of the armies. It is also used as music in Angampora [martial arts].

5. The Ritualizing of Ravana as Healer in the Annual Maha Ravana Nanumura Mangalyaya

This is done to pay tribute to all the talents and skills Ravana had. When 100 million people consider Ravana a villain and curse and burn his image every year, it is our responsibility to show the world his actual image and communicate the truth about him. We respect Ravana greatly because he is not a person destroying the world, Ravana keeps the world alive, Ravana is a person the world needs. If Ravana is allowed to come back to this world and work among the people he will be able to find solutions for the problems that prevail in the world. Ravana should be respected and loved more than this […].

It is held just once a year [it is special] because it is the Abhishekha, like a crowning ceremony. That makes it very special.

[…] after the nanumura mangalyaya is completed, we believe that the gods are pleased and that they are present. Bathing with the water and substances that were used will also do some good for us because of this reason.

Firstly, Ravana is believed to be the founder of medicine. Therefore, when the statue is washed it would evoke powers of healing; and generally when we show respect to any god he will send blessings to the people.

Have people found cures for certain diseases? Why do we let people die of sicknesses? Ravana has constantly kept saying, “people in this world cannot die because of sickness, they need to be cured.” Reasons behind why people get sick has to be looked into. Though Ravana challenges the world: if a person is terribly sick in bed and drawing their last breathes, we cannot let them die like that, that patient has to recover and then die. We are a pride nation born of Ravana’s blood.

Ravana was the first king in Sri Lanka and he had skills including medicine and dance […]. When you look at his personality and power even the substances connected to him should have some power.

The substances are believed to contain healing powers because they are used to bathe the Ravana statues. After these substances are used for the ritual, the substances are no longer ordinary: they gather some sort of power.

After they bathe the statue, the water and the substances collect a power that heals us when we bathe with it. The statue is first bathed. The power the statue gives, is used to heal us.

6. Reflection

The “-izing” ending is a deliberate attempt to suggest a process, a quality of nascence or emergence. Ritualizing is not often socially supported. Rather, it happens in the margins, on the thresholds; therefore it is alternately stigmatized and eulogized.

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- Ahubudu, Samanthi, and Relative of Arisen Ahubudu, Dehiwala, Sri Lanka. 2018. Group conversation with author, May 7.

- Angampora Teacher, and Katuwana, Sri Lanka. 2018. Interview with author, May 14.

- Assistant of Lay-Custodian Ravana Mandiraya, and Pannipitiya, Sri Lanka. 2018. Informal conversation with author, March 18.

- Attendant A of the Nanumura Mangalyaya, and Pannipitiya, Sri Lanka. 2018. Informal conversation with author, March 25.

- Attendant B of the Nanumura Mangalyaya, and Pannipitiya, Sri Lanka. 2018. Informal conversation with author, March 25.

- Beer, Robert. 2003. The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols. Boston: Shambhala, ISBN 9780834824232. [Google Scholar]

- Coperahewa, Sandagomi. 2012. Purifying the Sinhala Language: The Hela movement of Munidasa Cumaratunga (1930s–1940s). Modern Asian Studies 46: 857–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coperahewa, Sandagomi, and Senior Lecturer Department of Sinhala, University of Colombo, Colombo, Sri Lanka. 2018. Interview with author, April 18.

- Cumaratunga, Munidasa. 1941. Hela nama. Subasa 2: 392–95. [Google Scholar]

- Deegalle, Mahinda. 2004. Politics of the Jathika Hela Urumaya Monks: Buddhism and Ethnicity in Contemporary Sri Lanka. Contemporary Buddhism 5: 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegalle, Mahinda. 2011. Politics of the Jathika Hela Urumaya: Buddhism and Ethnicity. In The Sri Lanka Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Edited by Jonathan Holt. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 383–94. ISBN 9780822349822. [Google Scholar]

- Dharmadasa, Karuna N. O. 1995. Language, Religion, and Ethnic Assertiveness: The Growth of Sinhalese Nationalism in Sri Lanka. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, ISBN 9780472102884. [Google Scholar]

- Doniger, Wendy. 2010. The Hindus: An Alternative History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780199593347. [Google Scholar]

- Dutt, Manmatha Nath. 1894. Valmiki’s—The Rāmāyaṇa: Book 7 Uttara Kandam. Calcutta: Chackravarti, ISBN 9785872432791. [Google Scholar]

- Dutt, Michael Madhusudan. 2005. The Slaying of Meghanada: A Ramayana from Colonial Bengal. Translated by Clinton B. Seely. Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195167993. [Google Scholar]

- Facebook Webpage Sri Devram Maha Viharaya. 2018a. Available online: https://scontent-ams3-1.xx.fbcdn.net/v/t1.0-9/29683804_202516050522807_9130632977669086266_n.jpg?_nc_cat=0&oh=35cd4fe4e63d645f67f1b18247ddedd5&oe=5BB15CC3 (accessed on 29 June 2018).

- Facebook Webpage Sri Devram Maha Viharaya. 2018b. Available online: https://scontent-ams3-1.xx.fbcdn.net/v/t1.0-9/29570557_202516587189420_4982647518222686437_n.jpg?_nc_cat=0&oh=0a68c858777df26c4755cb4561860853&oe=5BE1C050 (accessed on 29 June 2018).

- Godakumbura, Charles E. 1993. Rāmāyaṇa in Śrī Laṅkā and Laṅkā of the Rāmāyaṇa. In A Critical Inventory of Rāmāyaṇa Studies in the World: 2. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, ISBN 8172015070. [Google Scholar]

- Gombrich, Richard. 2009. Buddhist Precept and Practice: Traditional Buddhism in the Rural Highlands of Ceylon, rev. ed. London: Routledge, ISBN 9780710304445. [Google Scholar]

- Gombrich, Richard F., and Gananath Obeyesekere. 1988. Buddhism Transformed: Religious Change in Sri Lanka. Princeton: Princeton University Press, ISBN 0691019010. [Google Scholar]

- Grimes, Ronald L. 2014. The Craft of Ritual Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195301434. [Google Scholar]

- Gunatilleke, Gehan. 2018. The Chronic and the Entrenched: Ethno-Religious Violence in Sri Lanka. Pannipitiya: Horizon Printing, ISBN 9789555802154. Available online: https://equitas.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/The-Chronic-and-the-Entrenched-FINAL-WEB-PDF.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2018).

- Henry, Justin. 2017. Distant Shores of Dharma: Historical Imagination in Sri Lanka from the Late Medieval Period. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, John. 2008. The Buddhist Viṣṇu: Religious Transformation, Politics, and Culture. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, ISBN 9788120832695. [Google Scholar]

- ITN Live Broadcasting of Perahera. 2017 March 25.

- Lay-Custodian of One of the Shrines of Bellanvila Raja Maha Viharaya, and Bellanvila, Colombo, Sri Lanka. 2018. Informal conversation with author. March 16. [Google Scholar]

- Lay-Custodian Ravana Mandiraya, and Pannipitiya, Sri Lanka. 2017a. Informal conversation with author, March 15.

- Lay-Custodian Ravana Mandiraya, and Pannipitiya, Sri Lanka. 2017b. Informal conversation with author, April 2.

- Lay-Custodian Ravana Mandiraya, and Pannipitiya, Sri Lanka. 2017c. Informal conversation with author, April 23.

- Lay-Custodian Ravana Shrine Kataragama, and Kataragama, Sri Lanka. 2018. Interview with author, April 17.

- Madin Maha Perahera (Procession) 2016. n.d. Available online: http://www.sridevramvehera.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=148&Itemid=185 (accessed on 23 January 2018).

- Madin Maha Perahera Meritorious Activity. n.d. Available online: http://www.sridevramvehera.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=152&Itemid=187 (accessed on 21 January 2018).

- Monk Galgamuwa, and Galgamuwa, Sri Lanka. 2017. Interview with author, April 4.

- Monk Vidurupola, and Vidurupola, Sri Lanka. 2016. Interview with author, March 11.

- Most Ven. Kolonnawe Sri Sumanagala Thero. n.d. Available online: http://sridevramvehera.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=57 (accessed on 9 January 2018).

- N.A. 2018. Devram Maha Vehere Medin Maha Perahera. Budumaga 4: 18–19. [Google Scholar]

- Obeyesekere, Mirando. 2016. Ravana Amaraniyayi. Hettigama: Samanthi Printers, ISBN 9789550841547. [Google Scholar]

- Official website of Arisen Ahubudu. n.d. Available online: https://www.ahubudu.lk/images/gallery/018.jpg (accessed on 29 June 2018).

- Organizing Monk Medin Maha Perahera, and Pannipitiya, Sri Lanka. 2017. Informal conversation with author, April 4.

- President of Ravana Shakti, and Nawinna, Sri Lanka. 2018. Interview with author, May 12.

- Rahula, Walpola. 1974. The Heritage of the Bhikku: A Short History of the Bhikku in Educational, Cultural, Social, and Political Life. Translated by K. P. G. Wijayasurendra and revised by Walpola Rahula. New York: Grove Press, ISBN 9780394178233. [Google Scholar]

- Rahula, Walpola. 2011. Politically Engaged Militant Monks. In The Sri Lanka Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Edited by Jonathan Holt. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 380–82. ISBN 9780822349822. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, Velcheru N. 1991. The Politics of Telegu Ramayanas: Colonialism, Print Culture, and Literary Movements. In Questioning Ramayanas: A South Asian Tradition. Edited by Paula Richman. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 159–86. ISBN 0520220730. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, Susan A. 2010. Dance and the Nation: Performance, Ritual, and Politics in Sri Lanka. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, ISBN 9780299231644. [Google Scholar]

- Richman, Paula. 1991. E.V. Ramasami’s Reading of the Ramayana. In Many Ramayanas: The Diversity of a Narrative Tradition in South Asia. Edited by Paula Richman. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 175–201. ISBN 9780520072817. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Richard H., and Willard L. Johnson. 1997. The Buddhist Religion: A Historical Introduction, 4th ed. Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing Group, ISBN 0534207189. [Google Scholar]

- Secretary Sumangala Thero, and Pannipitiya, Sri Lanka. 2017. Informal conversation with author, March 14.

- Secretary Sumangala Thero, and Pannipitiya, Sri Lanka. 2018a. Group conversation together with caretaker of the site, group conversation with author, March 11.

- Secretary Sumangala Thero, and Pannipitiya, Sri Lanka. 2018b. Informal conversation with author, February 25.

- Secretary Sumangala Thero and Caretaker of Temple Site, and Pannipitiya, Sri Lanka. 2018. Group conversation with author, March 11.

- Shukla, Anita. 2011. From Evil to Evil: Revisiting Ravana as a Tool for Community Building. In Villains and Villainy: Embodiments of Evil in Literature, Popular Culture and Media. Edited by Anna Fahraeus and Yakali-Çamoğlu Dikmen. Amsterdam: Rodopi, pp. 175–91. ISBN 9789401206808. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, Jonathan. 2014. Anthropology, Politics, and Place in Sri Lanka: South Asian Reflections from an Island Adrift. South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal 10: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumangala Thero. 2013. Vishvadipati Maha Ravana. Pannipitiya: Divya Ramya Jaya Maluva. [Google Scholar]

- Sumangala Thero. 2014. Sri Lankesvara Maha Ravana. Pannipitiya: Divya Ramya Jaya Maluva. [Google Scholar]

- Sumangala Thero, and Head Monk Sri Devram Maha Viharaya, Pannipitiya, Sri Lanka. 2017a. Informal conversation with author, March 25.

- Sumangala Thero, and Head Monk Sri Devram Maha Viharaya, Pannipitiya, Sri Lanka. 2017b. Interview with author, June 5.

- Sumangala Thero, and Head Monk Sri Devram Maha Viharaya, Pannipitiya, Sri Lanka. 2017c. Lecture, March 22.

- Sumangala Thero, and Head Monk Sri Devram Maha Viharaya, Pannipitiya, Sri Lanka. 2018. Interview with author, May 11.

- Suraweera, Alankarag V. 2014. Rājāvaliya: A Critical Edition with an Introduction. Nugegoda: Nanila Publications, ISBN 9789556652345. First published 2000. [Google Scholar]

- The History. n.d. Available online: http://sridevramvehera.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=61 (accessed on 19 January 2018).

- Volunteer Perahera, and Pannipitiya, Sri Lanka. 2018. Informal conversation with author, March 24.

- Volunteer Sri Devram Maha Viharaya, and Pannipitiya, Sri Lanka. 2018. Informal conversation with author, March 24.

- Volunteers Perahera, and Nawinna, Sri Lanka. 2018. Group conversation with author, March 9.

- Wickramasinghe, Nira. 2014. Sri Lanka in the Modern Age: A History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780190257552. [Google Scholar]

- Wickremeratne, Swarna. 2006. Buddha in Sri Lanka: Remembered Yesterdays. Albany: State University of New York Press, ISBN 079146881-X. [Google Scholar]

- Younger, Paul. 2002. Playing Host to Deity: Festival Religion in the South Indian Tradition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0195140443. [Google Scholar]

- Zuhair, Ayesha. 2016. Dynamics of Sinhala Buddhist Ethno-Nationalism in Post-War Sri Lanka. Colombo: Centre for Policy Alternatives, Available online: http://sangam.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/CPA-Dynamics-of-Sinhala-Buddhist-Ethno-Nationalism-in-Post-War-Sri-Lanka.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2018).

| 1 | The number of substances used to anoint the statues on Sunday evenings seemed to vary between nine and eleven. I assisted several times in the kitchen to prepare the necessities for the Ravana puja and I often counted nine big cups filled with porridges made out of herbal substances (such as turmeric and sandalwood) and two small ones filled with milk and king coconut. That for the latter two no ‘preparation’ is needed might explain the difference in the number of substances mentioned to me. The number and ingredients used for different rituals for Ravana are also prescribed by Sumangala Thero in for instance his book Sri Lankesvara Maha Ravana (Sumangala Thero 2014, pp. 45–47). |

| 2 | The reference to Ravana in the third stanza as the one who brings prosperity to paddy fields also occurs in popular publications in the Ravana discourse, for instance in one of the publications from the most famous writer in the Ravana discourse Mirando Obeyesekere. Obeyesekere has elaborated upon an irrigation system which allegedly was extant in Ravana’s time in the surroundings of Lakegala (Obeyesekere 2016, p. 79). According to him people in that area believe that this irrigation system dates back to Ravana’s time. The interactions between Ravana imaginations from rural lore (and Lakegala in particular) and imaginations from the Ravana discourse will be discussed in detail in my upcoming dissertation. |

| 3 | The role of one particular Hela representative for the current Ravana discourse with a special focus on the iconographic representation of Ravana within the Ravana discourse will be discussed in more detail in the third section of this article. |

| 4 | The Hela concept also appears in Sinhalese perception prior to the Hela movement (Dharmadasa 1995, pp. 20–21). |

| 5 | The first parts of the Mahavamsa have been written in the sixth century and after that it was updated three times: in the twelfth century, the fourteenth century, and the eighteenth century (Dharmadasa 1995, p. 4). |

| 6 | Examples of Hindu temples in Sri Lanka where this particular iconographic representation of Ravana is employed are the temples of Munnesvaram (visited 4 May 2016), Konesvaram (visited 23 March 2016), and the Nagapoosani Amman Kovil located on the island Nagadipa (visited 2 February 2016). |

| 7 | As discussed by Velcheru Narayana Rao the common core in the anti-Ramayana discourse in India is its anti-Brahmanism. The criticizing of pro-Brahmanic biases in Valmiki’s Ramayana appears for instance in retellings or rewritings of the Ramayana in Telegu and Tamil (Rao 1991, p. 162). As pointed out by Paula Richman for instance E.V. Ramasami, who is sometimes referred to as the founder of the Dravidian Movement, was more occupied with criticizing North Indians and the Ramayana than by defining a South Indian identity (Richman 1991, p. 197). In contrast to this anti-Ramayana discourse in the Indian context the Ravana myth under construction in Sri Lanka is not a retelling or rewriting of the Ramayana and the main focus within the current Ravana discourse is to construct a myth of Sinhalese-Buddhist national pride. |

| 8 | I have participated in the annual and weekly rituals for Ravana from 2016 onwards and conducted extensive fieldwork research at this Buddhist temple complex in 2017 and 2018. |

| 9 | In the manifesto of the JHU—which contains twelve points for constructing a righteous state—it is formulated that it is regarded as the duty of the government to protect Buddhism. Also, it states that the “[…] national heritage of a country belongs to the ethnic group who made the country into a habitable civilization” (Deegalle 2004, 2011, p. 391). Around the time of the opening of the Ravana mandiraya at the Sri Devram Maha Viharaya in 2013, also twelve goals of the temple complex were formulated by Sumangala Thero. These goals are put on display at one of the offices located at the Sri Devram Maha Viharaya. Roughly translated these goals are: (1) the protection/maintaining of the Sinhalese race/nation (to) protect/maintain the rights of other races/nations, (2) to make the ancient history/pedigree known to the young generation, (3) to give new life to agriculture, (4) to get the population used to the everyday living of Hela people, (5) to upkeep Ayurveda, (6) to take care of language, (7) to take care of music, dance, and rituals, (8) to give aid to/support new developments, (9) to create a young generation of bodhisattas (he who is going to become a Buddha), (10) to give aid/help to good intelligent children for education, (11) to take care of the older generation who gave power to our race/nation and, (12) to give to the youth a sense of ‘ourness’. Social activities organized by the Sri Devram Maha Viharaya such as housebuilding projects for poor people and the organization of blood donation campaigns, bear witness to the social engagement of Sumangala Thero and this temple complex. |

| 10 | In addition to shrines for gods located on the premises of a Buddhist temple complex there are also shrines in Sri Lanka not located on Buddhist sites (Gombrich and Obeyesekere 1988, p. xvi). |

| 11 | Gombrich and Obeyesekere refer to the officiant at a Sinhala shrine as a kapuva or kapurala (Gombrich and Obeyesekere 1988, p. xvi). At the Sri Devram Maha Viharaya the lay-custodian who is responsible for the Ravana mandiraya considered himself not a kapurala or kapuva but a care-taker. That the words kapurala or kapuva are less used at the Sri Devram Maha Viharaya is probably because the job is not inherited and it is not the custodians’ full-time occupation. |

| 12 | Other shrines for Ravana at Buddhist temple sites are for instance constructed at Boltumbe Saman devalaya (visited May 6, 2016) and Rambadagalla Viharaya in Kurunegalla (visited 2 March 2016). Also in Katuwana, there is a Ravana image enshrined in a cave and this is the only site where annually a small perahera for Ravana is organized. This perahera concentrates on the performances of Angampora and there are no elephants or chariots included. The statue taken around in the perahera is the Ravana statue from the shrine (Angampora Teacher 2018). |

| 13 | See for some recent examples of politically engaged Buddhist monks in Sri Lanka and the exceptional status of impunity they enjoy—even if they use violence—Gunatilleke 2018, pp. 77–82. |

| 14 | Examples are a monk from Vidurupola (Nuwara Eliya district) who delivered a speech on the day a movie about Rama and Ravana was released in Sri Lanka (around 2014) and a monk from Galgamuwa area who is publishing about the ancient yaksha language. Both monks consider Ravana the ancient king of Lanka. They did not conduct devotional activities for him. The latter monk explicated that Ravana has not be considered a god (Monk Vidurupola 2016; Monk Galgamuwa 2017). |

| 15 | In several informal conversations with visitors of the Sri Devram Maha Viharaya conducted in 2018 I asked them how and when their interest in Ravana started. They frequently answered that they learned about Ravana through newspaper articles, especially the ones written by Mirando Obeyesekere. |

| 16 | In addition to interviews with so called Ravana experts in TV- and radio programs, it is archaeological sites, caves and mountains which are discussed in length. These geographical spots allegedly proof the presence of Ravana and Lanka’s highly advanced civilization. Although there is some overlap with sites developed for Ramayana tourism in post-war Sri Lanka, in documentaries produced within the Ravana discourse mainly sites which are not storied within the Ramayana are discussed. See for some details of the development of Ramayana tourism Spencer (2014). |

| 17 | At one of the upper levels of the ‘sanctuary tower’ there is allegedly another Ravana statue kept. |

| 18 | Also in Sri Lanka some of the recently erected statues for Ravana at Buddhist complexes, for example the statue at Boltumbe Saman devalaya, depict Ravana with ten heads and twenty arms, This particular iconographic representation of Ravana is called dasis Ravana in Sinhalese, a contraction of dasa (ten) and hisa (head). |

| 19 | This information was gained through Ahubudu’s daughter (Ahubudu 2018). |

| 20 | An example of this is his book Hela Derana Vaga which has been translated into English and published in 2012 under the title The Story of the land of the Sinhalese (Helese). |

| 21 | http://ravanabrothers.com/open/ (accessed on 6 August 2018). |

| 22 | This is also the way the Ravana statue is molded in one of the earliest shrines for Ravana at the famous site of Kataragama. This shrine at Kataragama has been constructed under president Premadasa in 1987 (Lay-Custodian Ravana Shrine Kataragama 2018). At that time Ahubudu was appointed as consultant for president Premadasa (Coperahewa 2018). |

| 23 | I have not seen this statue at Maligavila myself and my observations of the statue are based on pictures published on the internet. Interestingly, a few more people from the Ravana discourse I talked with considered Ravana to be the same as Avalokitesvara. The particular objects (sword and scripture) are in Mahayana Buddhist iconography associated with another bodhisatta: Manjusri. With Manjusri both objects are connected to wisdom: the sword symbolizes the awareness of this bodhisatta which cuts through all delusion and the text indicates his mastery of all knowledge (Beer 2003, pp. 123–24; Robinson and Johnson 1997, pp. 106–7). In my fieldwork research (conducted in Sri Lanka which is primarily but not exclusively a Theravada Buddhist country) this bodhisatta was never referred to. |

| 24 | The word vedakama was used by the monk to denote this medicinal knowledge (Sumangala Thero 2018). |

| 25 | These interpretations are examples of answers given by people who were closely involved in the rituals performed for Ravana at the Sri Devram Maha Viharaya. Their answers show that a variety of interpretations even exists among the people who are closely involved in the rituals for Ravana. |

| 26 | The month March has been selected because the wedding of Buddha’s parents allegedly took place in that particular month (Madin Maha Perahera Meritorious Activity n.d.). |

| 27 | The first approximately 45 elements of the perahera are part of the theruwan puja maha perahera. This part shows similarities with the Kandy Esala perahera, the most famous perahera of Sri Lanka annually held in Kandy in honor of the sacred tooth relic of the Buddha. The tooth relic of the Buddha in Kandy is believed to be connected with rainfall (Wickremeratne 2006, p. 108). The tooth relic at the Sri Devram Maha Viharaya also allegedly belongs to Buddha. During the Medin maha perahera the relic is kept inside because taking it out is believed to cause extreme rainfall (Secretary Sumangala Thero 2018b). |

| 28 | An alternative symbolic interpretation of the ten heads is that Ravana is believed to have ruled ten countries. This interpretation is in the contemporary Ravana discourse less widespread than the opinion that his heads symbolizes skills. |

| 29 | I encountered a similar chariot with a depiction of the ten-headed Ravana on the front panel (knelt on one leg) and with similar hand gestures in the Munnesvaram (Hindu) Kovil (visited 4 May 2016). The chariot used in the Ravana perahera bears on the front panel also a wood carved image of the ten-headed Ravana who poses with various hand gestures and holds various objects in his numerous hands (of which some are broken). |

| 30 | The annual ritual of dasara is according to Anita Shukla one of the most popular symbols of the victory of good over evil in Indian culture (Shukla 2011, p. 175). However, as she also points to, the persona of Ravana is open to multiple interpretations. Also in India Ravana was seen as a good person from time to time. In for instance the nineteenth-century poem Meghanadavadha kavya (the slaying of Meghanada) composed by the Bengali poet Michael Madhusudan Datta both the characters Rama and Ravana are subject to transformation (Dutt 2005, p. 3). Ravana becomes in this poem the hero and his son Meghanada the symbol of the oppressed Hindus under the British rule (Doniger 2010, p. 667). Also, in the context of early twentieth century Dravidian nationalism (mainly 1930–1950) in India, E.V. Ramasami praised Ravana in his work as the true hero of the Ramayana and as a monarch of the ancient Dravidians (Richman 1991, pp. 175–201). A positive appropriation of Ravana can also be found among Tamils in Sri Lanka for instance in the temple literature of the famous Konesvaram temple (Henry 2017, p. 172). As Henry points to, influenced by the presence of Tamils in Sri Lanka, Ravana became accepted as a historical ruler in Sinhalese literature from the 14th century onwards, for instance in Kadayim (boundary books) and the Rajavaliya (Henry 2017, pp. 60–61, 148). |

| 31 | As he described in the ritual which he observed no laymen were allowed to witness the ritual and an exception was made for him as a researcher. As I also encountered, the information of the ritual is often not shared with outsiders. At several shrines for gods at Kataragama (visited 17 April 2018) and Kandy (visited 27–29 March 2018) I tried to gather information on the nanumura mangalyaya, but most of the lay-custodians were reluctant to give out information on this particular ritual. The ones who did, stressed that they normally do not share the details of the ritual with outsiders. |

| 32 | At Bellanvila Raja Maha Viharaya they perform a nanumura mangalyaya for all the statues of the gods in the shrines thrice a year: in January, around the time they have the annual perahera and with Sinhala New Year. (Lay-Custodian of One of the Shrines of Bellanvila Raja Maha Viharaya 2018). |

| 33 | On a list I received from one of the main caretakers of the site in 2017, after the maha Ravana nanumura mangalyaya, 23 ingredients were mentioned: sesame oil, rice flour, turmeric powder, raw turmeric, vada turmeric, sandanam, cows’ milk/buffalo milk, king coconut water, fruit sap, herbal leaves sap, lime juice, river water, lake water, sea water, rain water, vibuthi, kunkuma, red sandalwood, white sandalwood, scented water (rose water), jasmine water, pure water, and honey. |

| 34 | The role of kings and the legitimization of political power in the history of the Kandy Esala perahera is discussed in detail by Paul Younger. As he points to the Kandy Esala perahera aims to express loyalty to kingship and celebrates national identity (Younger 2002, pp. 69–79). |

| 35 | In the seventeenth century Rajavaliya it is said that there were 1844 years between the end of Ravana’s war and the enlightenment of Buddha (Suraweera [2000] 2014, p. 16). |

| 36 | A village ritual from the Kandyan district, the Kohomba yakkama, contains a different and complex story of Rama, Sita and Ravana from a Sinhalese perspective. This story is embedded into a particular Kuveni-Vijaya myth and, according to Godakumbura, known by a limited number of people only (Godakumbura 1993, p. xcv). Although, it was through state intervention by the end of the twentieth century turned into a kind of a heritage ritual (Reed 2010) it was never referred to by people in my fieldwork conversations. |

| 37 | As formulated in a policy rapport on Dynamics of Sinhala Buddhist Ethno-Nationalism in Post-War Sri Lanka (Zuhair 2016) the government under Rajapaksa nurtured a majoritarian mind-set among the Sinhalese majority which comprises between 70% and 75% of Sri Lanka’s population. Also, as pointed out by Gunatilleke, although Sirisena—who won the elections in 2015—expressed in his election manifesto a commitment to end ethno-religious violence, this promise has not been fulfilled (Gunatilleke 2018, pp. 1, 11; Zuhair 2016). Communal violence is for instance still commonplace in Sri Lanka. |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Koning, D. The Ritualizing of the Martial and Benevolent Side of Ravana in Two Annual Rituals at the Sri Devram Maha Viharaya in Pannipitiya, Sri Lanka. Religions 2018, 9, 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9090250

De Koning D. The Ritualizing of the Martial and Benevolent Side of Ravana in Two Annual Rituals at the Sri Devram Maha Viharaya in Pannipitiya, Sri Lanka. Religions. 2018; 9(9):250. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9090250

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Koning, Deborah. 2018. "The Ritualizing of the Martial and Benevolent Side of Ravana in Two Annual Rituals at the Sri Devram Maha Viharaya in Pannipitiya, Sri Lanka" Religions 9, no. 9: 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9090250