Brazilian Validation of the Attachment to God Inventory (IAD-Br)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Attachment to God Inventory—A Brief Theoretical Background

2.1. Validation of the Attachment to God Inventory (AGI) In the USA and Canada

2.2. Validation of the AGI in Taiwan

2.3. Validation of the AGI in Italy

The original instrument was mainly developed on a sample of believers, protestant groups with a high percentage of women, while our sample is more heterogeneous and more balanced for sex.

2.4. Validation of the AGI in Korea

3. Method

3.1. Translation and Adaptation

3.2. Sample

4. Results and Discussion

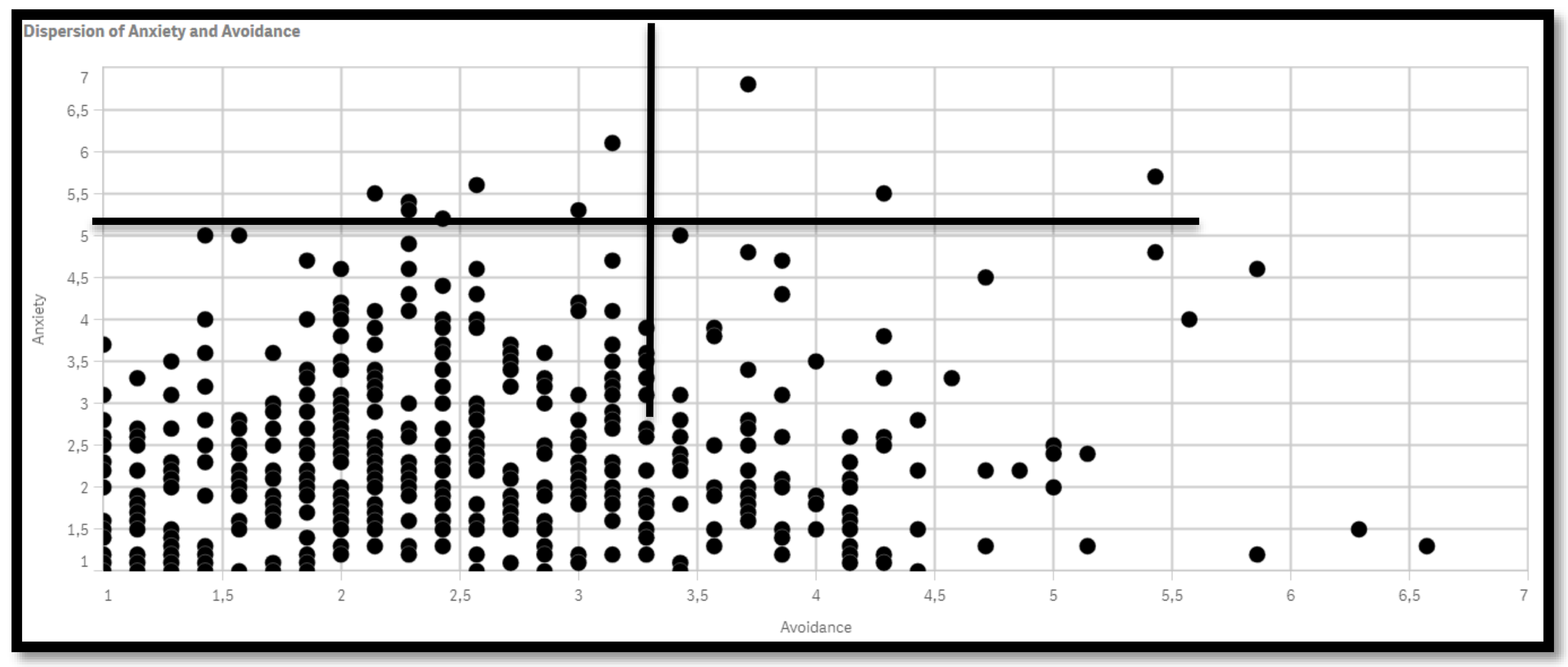

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Refinements of the IAD-Br

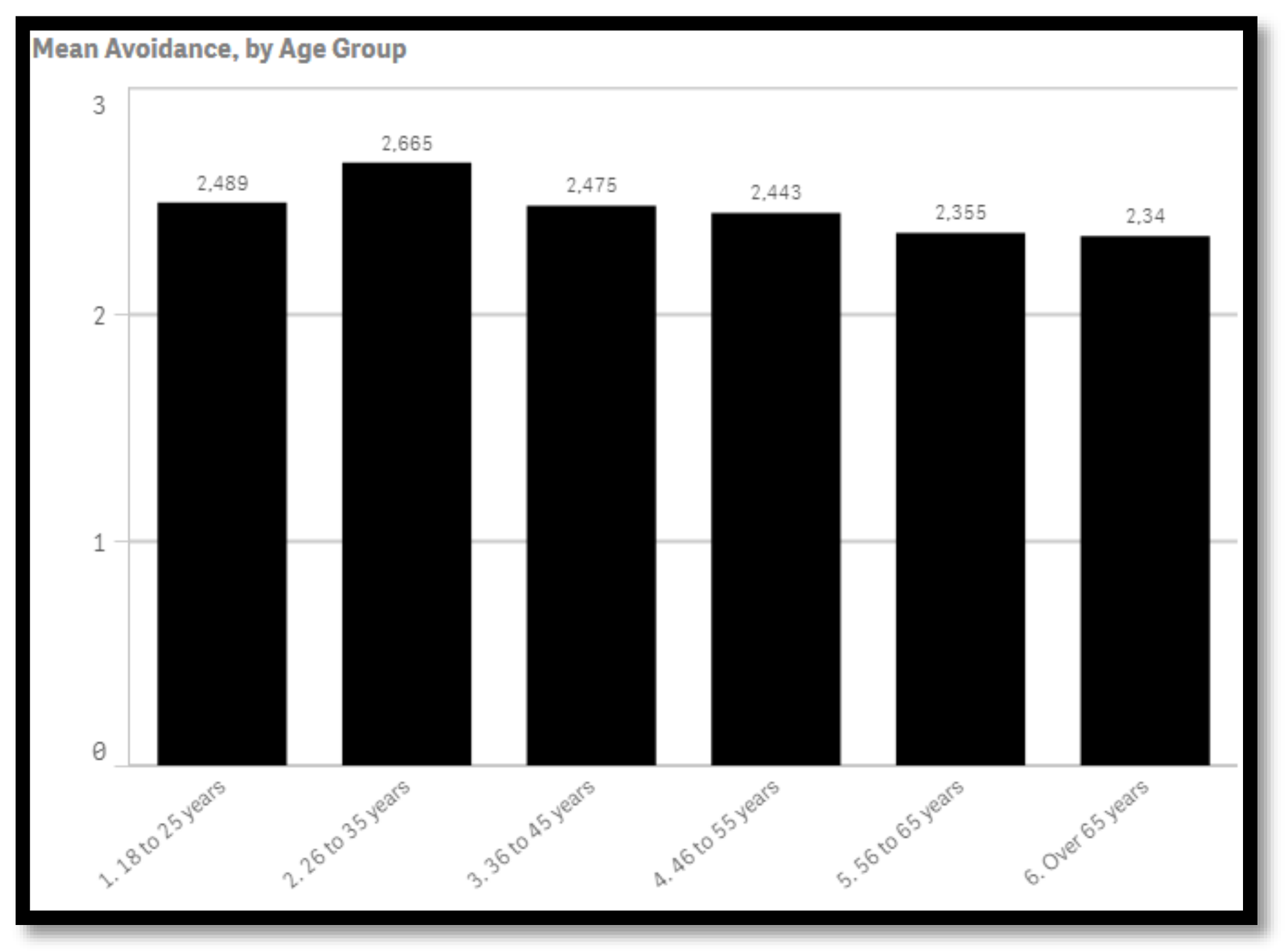

4.1.1. Attachment to God Style and Age Group

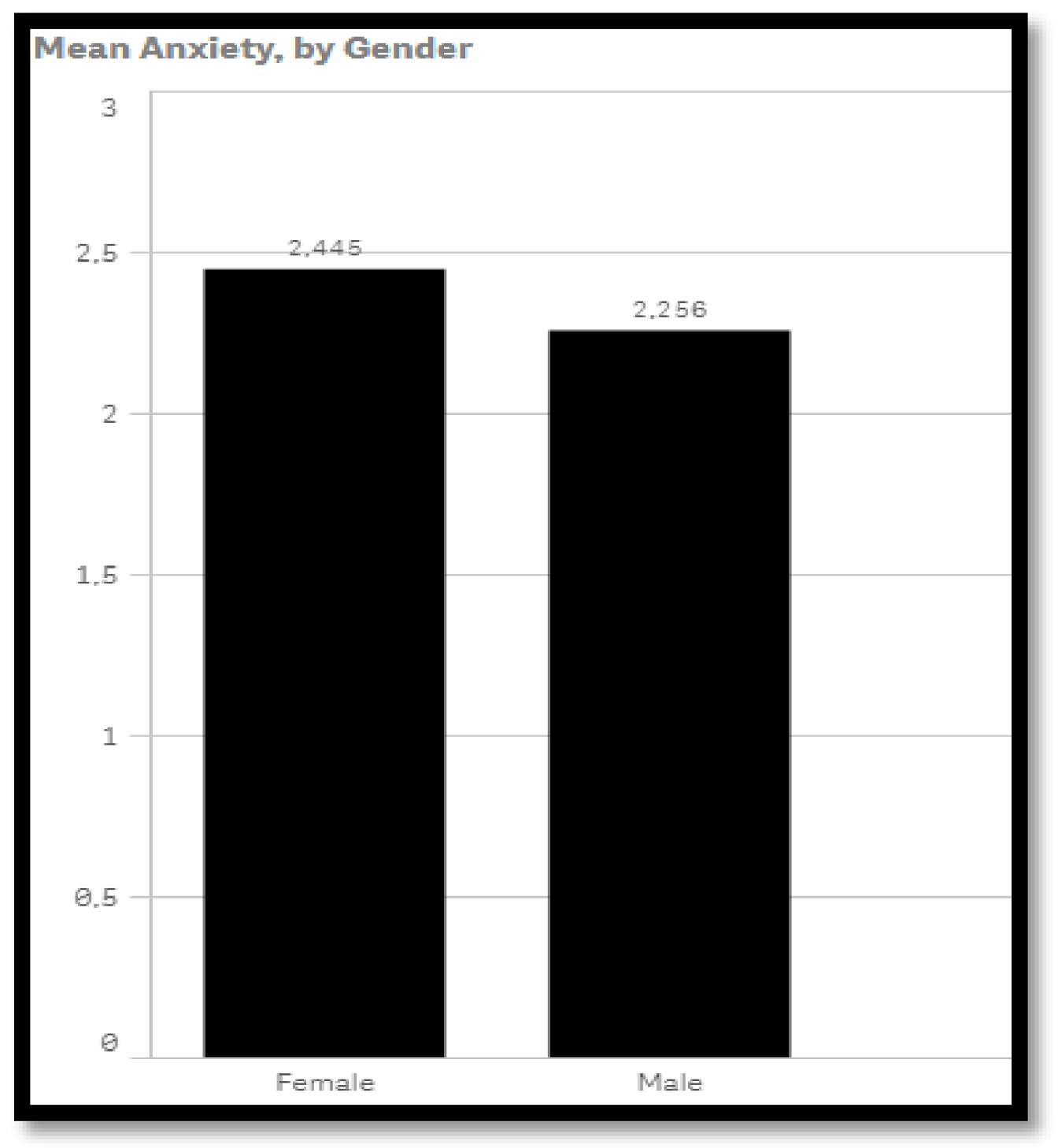

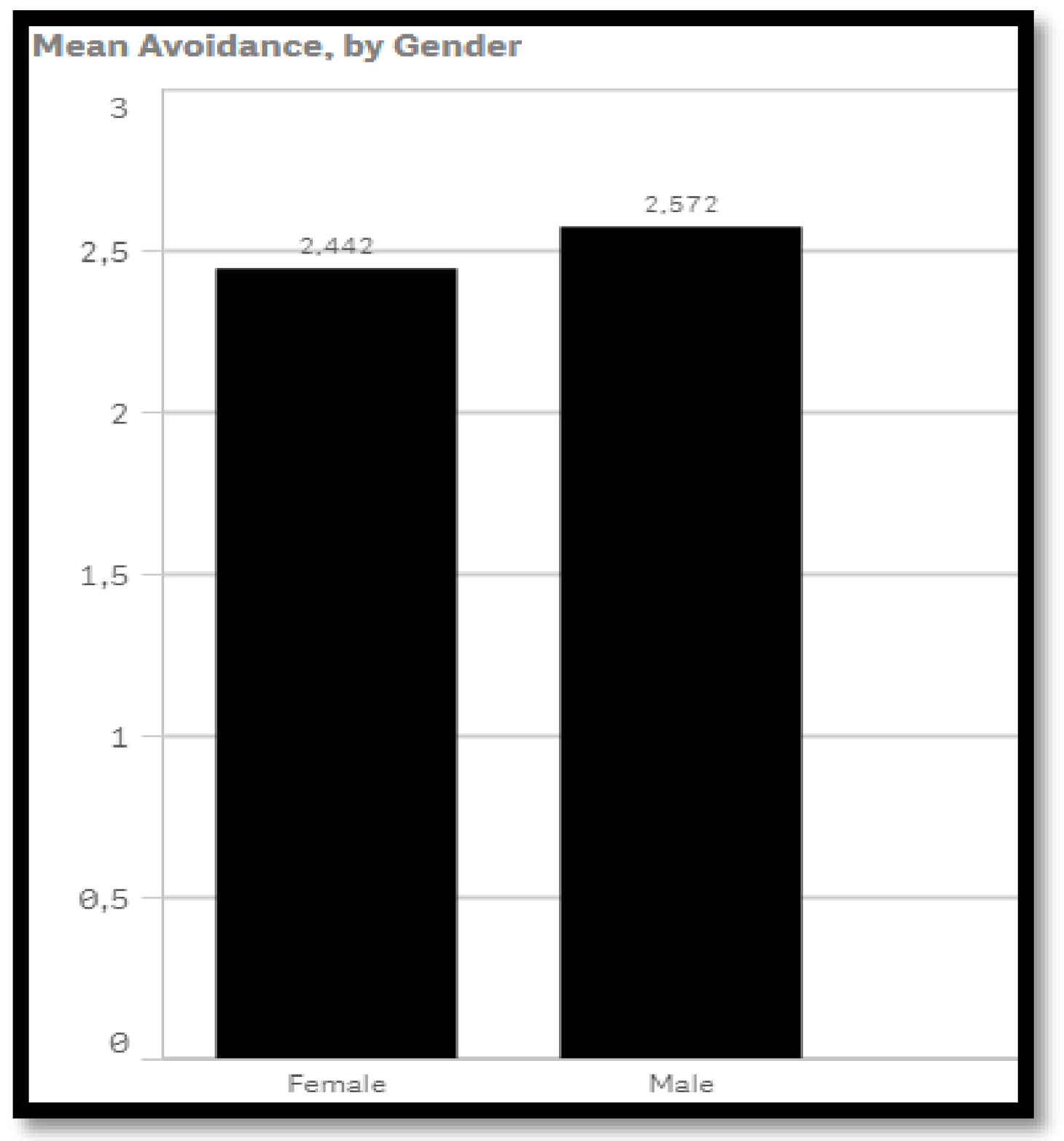

4.1.2. Attachment to God Style and Gender

4.1.3. Attachment to God Style and Schooling

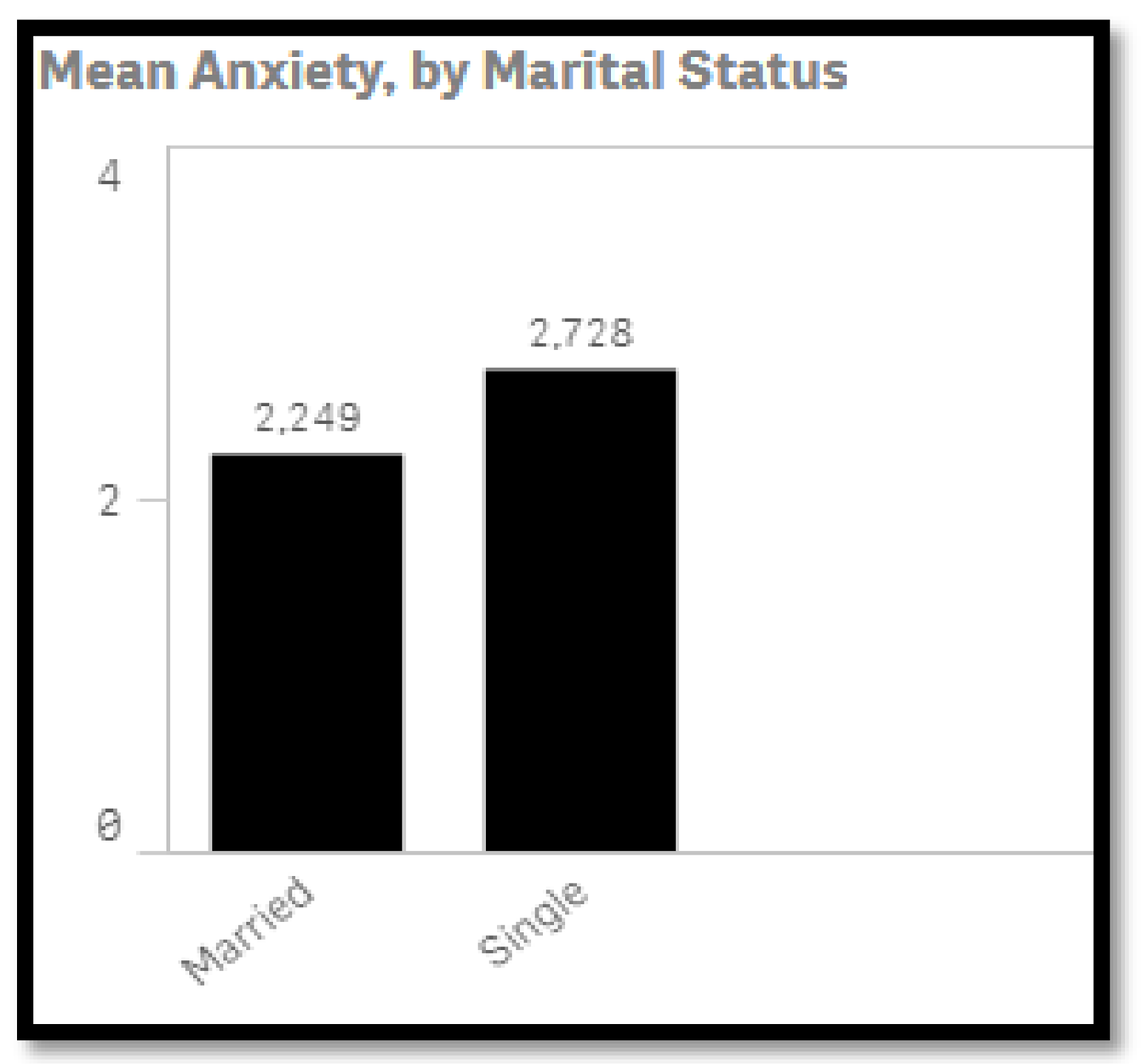

4.1.4. Attachment to God Style and Marital Status

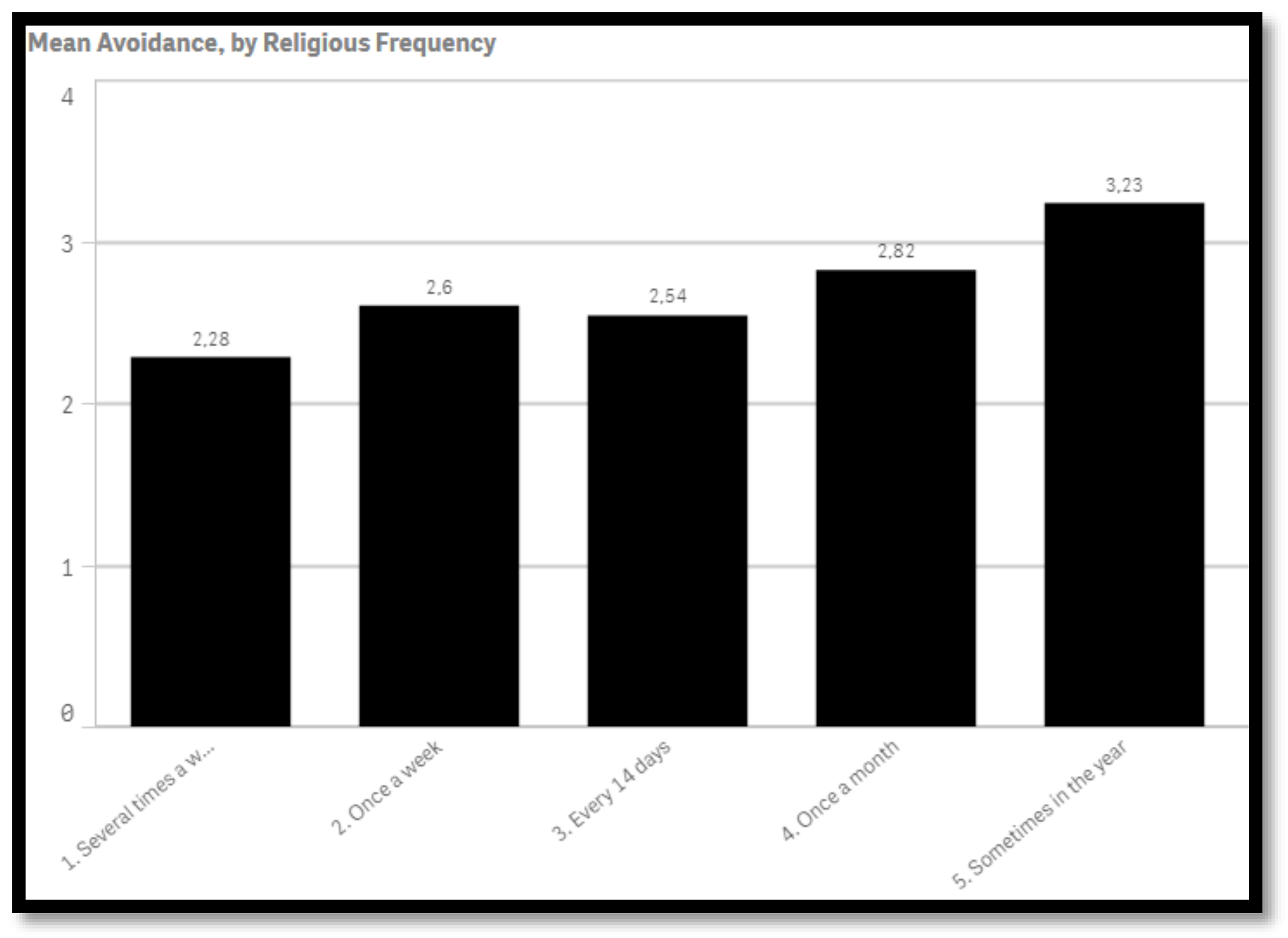

4.1.5. Attachment to God Style and Religious Frequency

4.1.6. Attachment to God Style and Belonging to the Religious Community

4.2. Culture Influences the Expression of Faith

The Brazilian ritual system is a complex mode of establishing and even proposing a permanent and strong relation between the house and the street, between ‘this world’ and the ‘other world’. In other words, the festivity, ceremonial, ritual and solemn moment are modalities of relating separate and complementary sets of the same social system.

4.3. Limitations and Future Studies

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Inventário de Apego a Deus—Versão Brasileira (IAD-Br)—In Portuguese

| Discordo Fortemente | Discordo | Discordo Moderadamente | Não Concordo; Nem Discordo | Concordo Moderadamente | Concordo | Concordo Fortemente | |||

| 1 | Sou totalmente dependente de Deus para tudo na minha vida. | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| 2 | Prefiro não depender muito de Deus. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 3 | Sem Deus eu não consigo fazer nada. | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| 4 | Eu acredito que as pessoas não deveriam depender de Deus para fazer as coisas que elas deveriam fazer sozinhas. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 5 | Diariamente eu discuto todos os meus problemas e preocupações com Deus. | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| 6 | Eu fico desconfortável em deixar que Deus controle cada aspecto da minha vida. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 7 | Eu deixo que Deus tome a maior parte das decisões na minha vida. | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Soma 1 | |||||||||

| 8 | Se eu não vejo Deus agindo em minha vida, eu fico chateado(a) ou com raiva. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 9 | Tenho ciúmes da forma como Deus parece cuidar mais dos outros do que de mim. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 10 | Às vezes sinto que Deus ama os outros mais do que a mim. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 11 | Tenho ciúmes da proximidade que algumas pessoas têm com Deus. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 12 | Quase diariamente sinto que minha relação com Deus é oscilante, vai de “intensa” a “fria”. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 13 | Temo que Deus não me aceite quando faço algo errado. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 14 | Muitas vezes fico bravo(a) com Deus quando Ele não me responde quando quero. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 15 | Eu preciso intensamente que Deus reafirme o seu amor por mim. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 16 | Eu fico com ciúmes quando outros sentem a presença de Deus e eu não. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 17 | Eu fico chateado(a) quando sinto que Deus ajuda outros, mas se esquece de mim. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Soma 2 | |||||||||

| Dimensão da Evitação a Deus Soma 1: _____ : 7 = ______ | Dimensão da Ansiedade a Deus Soma 2: _____ : 10 = ______ | ||||||||

Appendix B. The Attachment to God Inventory

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Disagree | Neutral/Mixed | Agree | ||||

| Strongly | Strongly |

References

- Abreu, Cristiano Nabuco de. 2005. Teoria do Apego—Fundamentos, Pesquisas e Implicações Clínicas. São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Ales Bello, Angela. 1998. Culturas e Religiões: Uma Leitura Fenomenológica. Bauru: EDUSC. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Beck, Richard. 2006a. Communion and Complaint: Attachment, object-relations, and triangular love perspectives on relationship with God. Journal of Psychology and Theology 34: 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, Richard. 2006b. God as a secure base: Attachment to God and theological exploration. Journal of Psychology and Theology 34: 125–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, Richard, and Angie McDonald. 2004. Attachment to God: The Attachment to God Inventory, Tests of Working Model Correspondence, and an Exploration of Faith Group Differences. Journal of Psychology and Theology 32: 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, John. 1988. A Secure Base: Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, John. 2002. Apego e Perda: Apego, V. 1 Da Trilogia, 3rd ed. São Paulo: Martins Fontes. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, John. 2004a. Apego e Perda: Perda: Tristeza e Depressão. V. 3 Da Trilogia. São Paulo: Martins Fontes. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, John. 2004b. Apego e Perda: Separação: Angústia e Raiva. V. 2 Da Trilogia. São Paulo: Martins Fontes. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, Kelly A., Catherine L. Clark, and Phillip R. Shaver. 1998. Self-report measures of adult romantic attachment. An integrative overview. In Attachment Theory and Close Relationships. Edited by Jeffry A. Simpson and William Steven Rholes. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, A. Jerry, Laura B. Cooper, S. Thomas Kordinak, and Marsha J. Harman. 2011. God and Sin after 50: Gender and Religious Affiliation. Journal of Religion, Spirituality & Aging 23: 224–35. [Google Scholar]

- Cicirelli, Victor G. 2010. Attachment relationships in old age. Journal of Social & Personal Relationships 27: 191–99. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, Laura B., A. Jerry Bruce, Marsha J. Harman, and Marcus T. Boccaccini. 2009. Differentiated styles of attachment to God and varying religious coping efforts. Journal of Psychology and Theology 37: 134–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DaMatta, Roberto. 1997. A Casa & a Rua: Espaço, Cidadania, Mulher e Morte No Brasil, 5th ed. Rio de Janeiro: Rocco. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Dumont, Karin, David Jenkins, Victor Hinson, and Gary Sibcy. 2012. God’s shield: The relationship between god attachment, relationship satisfaction, and adult child of an alcoholic (ACOA) status in a sample of evangelical graduate counseling students. Journal of Psychology and Christianity 31: 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Esperandio, Mary Rute G., and Hartmut August. 2014. Teoria do Apego e Comportamento Religioso. Interações—Cultura e Comunidade, Belo Horizonte, Brasil 16: 243–65. (In Portuguese). [Google Scholar]

- Freeze, Tracy A., and Enrico Ditommaso. 2014. An examination of attachment, religiousness, spirituality and well-being in a Baptist faith sample. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 17: 690–702. [Google Scholar]

- Freeze, Tracy A., and Enrico Ditommaso. 2015. Attachment to God and church family: Predictors of spiritual and psychological well-being. Journal of Psychology and Christianity 34: 60–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbani-Bonab, Bagher, Maureen Miner, and Marie-Therese Proctor. 2013. Attachment to God in Islamic spirituality. Journal of Muslim Mental Health 7: 77–104. [Google Scholar]

- Granqvist, Pehr, and Lee A. Kirkpatrick. 2004. Religious Conversion and Perceived Childhood Attachment: A Meta-Analysis. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 4: 223–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granqvist, Pehr, and Lee A. Kirkpatrick. 2013. Religion, spirituality, and attachment. In APA Handbook for the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality (Vol 1): Context, Theory, and Research. Edited by Kenneth I. Pargament. Washington: American Psychological Association, pp. 129–55. [Google Scholar]

- Guilford, Joy Paul. 1954. Psychometric Methods, 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, Joseph F., Jr., Rolph E. Anderson, Ronald L. Tatham, and William. C. Black. 2009. Análise Multivariada de Dados, 6th ed. Porto Alegre: Bookman. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Todd W., Annie Fujikawa, Sarah R. Halcrow, Peter C. Hill, and Harold Delaney. 2009. Attachment to god and implicit spirituality: Clarifying correspondence and compensation models. Journal of Psychology and Theology 37: 227–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homan, Kristin J. 2012. Attachment to God mitigates negative effect of media exposure on women’s body image. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 4: 324–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homan, Kristin J. 2014. A mediation model linking attachment to God, self-compassion, and mental health. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 17: 977–89. [Google Scholar]

- Homan, Kristin J., and Chris J. Boyatzis. 2010. The protective role of attachment to God against eating disorder risk factors: Concurrent and prospective evidence. Eating Disorder 18: 239–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homan, Kristin J., and Valerie A. Lemmon. 2014. Attachment to God and eating disorder tendencies: The mediating role of social comparison. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 6: 349–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homan, Kristin J., and Valerie A. Lemmon. 2015. Perceived relationship with God moderates the relationship between social comparison and body appreciation. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 18: 425–39. [Google Scholar]

- Houser, Melissa E., and Ronald D. Welch. 2013. Hope, religious behaviors, and attachment to god: A trinitarian perspective. Journal of Psychology and Theology 41: 281–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Li-tze, and Peter M. Bentler. 1999. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indices in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus New Alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 6: 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE. 2010. Censo Demográfico. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE, 2000. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/index.php (accessed on 18 March 2018).

- Kim, Pio, Sangwon Kim, Fran Blumberg, and Jihee Cho. 2017. Validation of the Korean Attachment to God Inventory. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, Lee. 2005. Attachment, Evolution, and the Psychology of Religion. New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, Lee A., and Phillip R. Shaver. 1990. Attachment Theory and Religion. Childhood Attachments, Religious Beliefs and Conversion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 29: 315–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knabb, Joshua J., and Joseph Pelletier. 2014. The relationship between problematic Internet use, God attachment, and psychological functioning among adults at a Christian university. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 17: 239–51. [Google Scholar]

- Limke, Alicia, and Patrick B. Mayfield. 2011. Attachment to God: Differentiating the contributions of fathers and mothers using the experiences in parental relationships scale. Journal of Psychology and Theology 39: 122–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, Robert C., Keith Widaman, Shaobo Zhang, and Sehee Hong. 1999. Sample size in factor analysis. Psychological Methods 4: 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeland, Elisabeth. 2013. Attachment and Prayer a Critical Analysis of Relationships among Attachment Experiences and Perceived Relation to God in Prayer. Master’s thesis, Det Teologiske Menighetsfakultet, Oslo, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Mario, Mikulincer, and Philip R. Shaver. 2010. Attachment in Adulthood—Structure, Dynamics, and Change. New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Miner, Maureen, Bagher Ghorbany-Bonab, Martin Dowson, and Marie-Therese Proctor. 2014. Spiritual attachment in Islam and Christianity. Mental Health, Religion and Culture 17: 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, Maureen, Bagher Ghobary-Bonab, and Martin Dowson. 2017. Development of a Measure of Attachment to God for Muslims. Review of Religious Research 59: 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niebuhr, H. Richard. 1967. Cristo e Cultura. Série Encontros e Diálogos. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, vol. 3. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Olson, Trevor, Theresa Clement Tisdale, Edward B. Davis, Elizabeth A. Park, Jiyun Nam, Glendon L. Moriarty, Don E. Davis, Michael J. Thomas, Andrew D. Cuthbert, and Lance W. Hays. 2016. God image narrative therapy: A mixed-methods investigation of a controlled group-based spiritual intervention. Spirituality in Clinical Practice 3: 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prout, Tracy A., John Cecero, and Dianna Dragatsi. 2012. Parental object representations, attachment to God, and recovery among individuals with psychosis. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 15: 449–66. [Google Scholar]

- Rasar, Jacqueline D., Fernando L. Garzon, Frederick Volk, Carlmella A. O’Hare, and Glendon L. Moriarty. 2013. The efficacy of a manualized group treatment protocol for changing god image, attachment to god, religious coping, and love of god, others, and self. Journal of Psychology and Theology 41: 267–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichenheim, Michael, and Claudia Moraes. 2007. Operacionalização de adaptação transcultural de instrumentos de aferição usados em epidemiologia. Revista de Saúde Pública 41: 665–73. (In Portuguese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiner, Sarah R., Tamara L. Anderson, M. Elizabeth Lewis Hall, and Todd W. Hall. 2010. Adult attachment, God attachment and gender in relation to perceived stress. Journal of Psychology and Theology 38: 175–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, Germano, and Angela Tagini. 2011. The Attachment to God Inventory (AGI, Beck & MacDonald, 2004): An Italian Adaptation. Available online: http://www.germanorossi.it/pubb/C71_2011_RosTag.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2016).

- Thomas, Michael J., Glendon L. Moriarty, Edward B. Davis, and Elizabeth L. Anderson. 2011. The effects of a manualized group-psychotherapy intervention on client God images and attachment to God: A pilot study. Journal of Psychology and Theology 39: 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Assche, Lies, Patrick Luyten, Lucas Van de Ven, and Mathieu Vandenbulcke. 2013. The impact of attachment on behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia. Tijdschr Gerontol Geriatr 44: 157–65. [Google Scholar]

- Yeo, Ju-Ping Chiao. 2011. The Psychometric Study of the Attachment to God Inventory and the Brief Religious Coping Scale in a Taiwanese Christian Sample. Ph.D. dissertation, Liberty University, Lynchburg, VA, USA. Available online: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/doctoral/458 (accessed on 27 October 2016).

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. I worry a lot about my relationship with God | −0.09 | -- |

| (Eu me preocupo muito com meu relacionamento com Deus) | ||

| 2. I just don’t feel a deep need to be close to God | 0.20 | -- |

| (Eu não sinto uma necessidade tão grande de estar próximo(a) a Deus) | ||

| 3. If I can’t see God working in my life, I get upset or angry | 0.53 | 0.51 |

| (Se eu não vejo Deus agindo em minha vida, eu fico chateado(a) ou com raiva) | ||

| 4. I am totally dependent upon God for everything in my life (R) | 0.70 | 0.74 |

| (Sou totalmente dependente de Deus para tudo na minha vida) | ||

| 5. I am jealous at how God seems to care more for others than for me | 0.78 | 0.74 |

| (Tenho ciúmes da forma como Deus parece cuidar mais dos outros do que de mim) | ||

| 6. It is uncommon for me to cry when sharing with God | 0.31 | -- |

| (Não é habitual eu chorar quando estou em comunhão com Deus) | ||

| 7. Sometimes I feel that God loves others more than me | 0.70 | 0.69 |

| (Às vezes sinto que Deus ama os outros mais do que a mim) | ||

| 8. My experiences with God are very intimate and emotional (R) | 0.43 | -- |

| (Minhas experiências com Deus são muito íntimas e emocionais) | ||

| 9. I am jealous at how close some people are to God | 0.67 | 0.64 |

| (Tenho ciúmes da proximidade que algumas pessoas têm com Deus) | ||

| 10. I prefer not to depend too much on God | 0.64 | 0.62 |

| (Prefiro não depender muito de Deus) | ||

| 11. I often worry about whether God is pleased with me | 0.11 | -- |

| (Com frequência me preocupo se Deus está satisfeito comigo) | ||

| 12. I am uncomfortable being emotional in my communication with God | 0.15 | -- |

| (Sinto-me desconfortável se minha comunicação com Deus é emocional) | ||

| 13. Even if I fail, I never question that God is pleased with me (R) | −0.01 | -- |

| (Mesmo quando eu falho, nunca me pergunto se Deus está contente comigo) | ||

| 14. My prayers to God are often matter-of-fact and not very personal | 0.28 | -- |

| (Minhas orações a Deus frequentemente são práticas e não muito pessoais) | ||

| 15. Almost daily, I feel that my relationship with God goes back and forth from “hot” to “cold” | 0.48 | 0.48 |

| (Quase diariamente sinto que minha relação com Deus é oscilante, vai de “intensa” a “fria”) | ||

| 16. I am uncomfortable with emotional displays of affection to God | 0.33 | -- |

| (Sinto-me desconfortável com demonstrações emocionais de afeto a Deus) | ||

| 17. I fear God does not accept me when I do wrong | 0.45 | 0.45 |

| (Temo que Deus não me aceite quando faço algo errado) | ||

| 18. Without God I could not function at all (R) | 0.61 | 0.63 |

| (Sem Deus eu não consigo fazer nada) | ||

| 19. I often feel angry with God for not responding to me when I want | 0.64 | 0.62 |

| (Muitas vezes fico bravo(a) com Deus quando Ele não me responde quando quero) | ||

| 20. I believe people should not depend on God for things they should do for themselves | 0.49 | 0.48 |

| (Eu acredito que as pessoas não deveriam depender de Deus para fazer as coisas que elas deveriam fazer sozinhas) | ||

| 21. I crave reassurance from God that God loves me | 0.42 | 0.42 |

| (Eu preciso intensamente que Deus reafirme o seu amor por mim) | ||

| 22. Daily I discuss all of my problems and concerns with God (R) | 0.45 | 0.42 |

| (Diariamente eu discuto todos os meus problemas e preocupações com Deus) | ||

| 23. I am jealous when others feel God’s presence when I cannot | 0.68 | 0.70 |

| (Eu fico com ciúmes quando outros sentem a presença de Deus e eu não) | ||

| 24. I am uncomfortable allowing God to control every aspect of my life | 0.52 | 0.51 |

| (Eu fico desconfortável em deixar que Deus controle cada aspecto da minha vida) | ||

| 25. I worry a lot about damaging my relationship with God | 0.11 | -- |

| (Preocupo-me bastante com a possibilidade de eu prejudicar meu relacionamento com Deus) | ||

| 26. My prayers to God are very emotional (R) | 0.21 | -- |

| (Minhas orações a Deus são muito emocionais) | ||

| 27. I get upset when I feel God helps others, but forgets about me | 0.81 | 0.83 |

| (Eu fico chateado(a) quando sinto que Deus ajuda outros, mas se esquece de mim) | ||

| 28. I let God make most of the decisions in my life (R) | 0.67 | 0.69 |

| (Eu deixo que Deus tome a maior parte das decisões na minha vida) |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety about Abandonment by God | ||

| Cronbach’s Alpha | 0.80 | 0.85 |

| Composite Reliability | 0.80 | 0.91 |

| Average Variance Extracted | 0.29 | 0.50 |

| Avoidance of Intimacy with God | ||

| Cronbach’s Alpha | 0.76 | 0.77 |

| Composite Reliability | 0.77 | 0.87 |

| Average Variance Extracted | 0.22 | 0.50 |

| P | Χ2 | DF | Χ2/DF | RMSEA | GFI | AGFI | CFI | NFI | SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 2 | <0.001 | 244.860 | 114 | 2.148 | 0.049 | 0.942 | 0.922 | 0.949 | 0.909 | 0.067 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

August, H.; Esperandio, M.R.G.; Escudero, F.T. Brazilian Validation of the Attachment to God Inventory (IAD-Br). Religions 2018, 9, 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9040103

August H, Esperandio MRG, Escudero FT. Brazilian Validation of the Attachment to God Inventory (IAD-Br). Religions. 2018; 9(4):103. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9040103

Chicago/Turabian StyleAugust, Hartmut, Mary Rute G. Esperandio, and Fabiana Thiele Escudero. 2018. "Brazilian Validation of the Attachment to God Inventory (IAD-Br)" Religions 9, no. 4: 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9040103