1. Introduction

Economic progression of the societies and modernization of the social institutions often leads to the ‘culture of consumption’, and the people of those societies adopt Materialistic value-orientation. Materialistic values imply the belief that it is imperative to seek the culturally sanctioned aims of a financial prosperity, having admirable possessions, possessing the right impression formed through consumer goods, and obtaining a high status determined by the volume of one’s pocketbook (

Kasser et al. 2004). When materialism becomes one of the dominant normative values, people prioritize the secondary needs for material comfort over the primary needs such as quality of social life or sense of belongingness (

Richins and Dawson 1992). The pursuit of profit, power, efficiency, and competitiveness turns into the chief drivers for everyday lives (

Belk 1985). This, for obvious reason, brings changes to the other normative disposition, say an “individual’s conviction, devotion, and veneration towards a divinity”, known as ‘religiosity’ (

Gallagher and Tierney 2013). However, the transformation of religion as a fundamental social institution and changing pattern of religiosity of an individual is a matter of argument; as it currently stands, three traditions primarily deal with the normative shift. Some argue that economy-related activities and religion-centered behavior do not collaborate together well, and an economy based on religious values is unsustainable in a globalized economy (

Belk 1985;

Gould 1991;

Pace 2013). In a society where values center around material success, prestige, purchasing power or comfort, religious moral values tend to fall into desuetude (

Norris and Inglehart 2005). Those who argue as such are chiefly the descendants of the ‘Secularization thesis’. Some others argue, in order to deal with the unsettling emotional, political, economic and social consequences due to the financial progression and modernization, that people often gravitate their hold towards traditional normative beliefs and religious morals. From a theoretical landscape, these acts are sometimes interpreted as the ‘Religious Revivalism’. The third argument (mostly developed in the American religious landscape of about the 1940s) is material prosperity and is the eventuality of the proper acts of the true believers (

Roof 1979). This transdenominational doctrine—known as the “prosperity gospel”—is arguably aligned with the prospects and compelling nature of the free market to foster the culture of capitalism (

Patterson 2006). While the aforementioned theoretical stands that deal with the position of religion at the societal spheres are in a way a macro-level orientation, there is no way of denying that these approaches, explicitly or implicitly, offers the meso-level explanation of the changing pattern of the religiosity at present.

First, the ‘Secularization theory’ posits that modernization has a negative effect on the significance of religion in the social spheres. The theory claims that the social importance of religion in modern societies is declining in comparison to earlier eras (

Wilson 2014). The premodern cultures attribute preeminent importance to church and religion that the modern ones lack. While classical thinkers predicted that the technological achievement and economic progression of the society will bring changes to the notions of religious beliefs, ideas or concepts, and constructs, and eventually will dissolve it (

Freud 1971), the modern proponents of the theory, however, implies that “nothing in the social world inevitable” (

Norris and Inglehart 2004). They also indicate, “Some outcomes seem more probable than others” (

Voas and Doebler 2011). Though it is not conclusively proven (or unproven), the economic growth led to a decline in religion; nonetheless, it is evident that financial prosperity has a negative effect on some attributes of religiosity, such as church attendance (

McCleary and Barro 2006b). Second, the ‘Religious Revivalism’ is a defense mechanism towards the modernization, and sometimes the westernized notion of ‘development’ and economic progression. It is as if “the importance of the religion factor in public life is not decreasing or remaining static but is increasing in almost every part of the world” (

Shah 2004). Since religion often declares prohibitory behavioral rules in the economic sphere, people who are very religious, repeal from taking a keen interest in economy-centered activities. For example, in the Holy Quran, it is said, “You are obsessed by greed for more and more until you go down to your graves. Nay, in time you will come to understand!” (Al-Quran, 102: 1–3). In Christianity, Jesus preaches, “Do not store up for yourselves treasure on earth, where it grows rusty and moth-eaten and thieves break in to steal it” (Matthew 6: 19). The Bhagavad Gita says “Pondering on objects of the senses gives rise to attraction; from attraction grows desire, desire flames to passion, passion breeds recklessness; and then betrayed memory lets noble purpose go, and saps the mind, till purpose, mind, and man are all undone”. Taoism has the aphorism, “Chase after money and security, and your heart will never unclench”. This negates the culture of consumption. Third, Prosperity theology considers spiritual essence and physical existences are a single inseparable reality (

Hunt 2000), where prosperity is an “inviolable contract between God and humanity” (

Van Biema 2006), and wealth is God’s blessings (

Wilson 2007). However, a kind of similar notion can be traced in classical sociology, where it is argued that the Protestant work ethic (particularly Calvinism) was a major force behind the unplanned and uncoordinated development of modern capitalism, and economic prosperity is the “sign” of salvation (

Weber 1920); nonetheless, the prosperity gospel is distinct as it is a teaching about the “divine healing” (

Bowler 2010) and “Science of the Mind” (

Harrell 1975).

At this juncture, it is pertinent to consider that either ‘Materialism’ and ‘Religiosity’ are two of the most incompatible yet dominant components of normative value-systems that are always in contention with each other, or religion remains a potent factor in the changing economic times and state of conflicts, and have no significant effect of materialistic value-orientation. Let’s not forget that materialistic values are the endogenous characteristics influenced by the external environment; hence, the level of wealth and life experiences can cause differences in the state of materialistic value-orientation from one person to another, or across the life-course of a single individual. Therefore, three propositions can be derived. First, based on the ‘religious revivalism’, (H0) religious values would be so strong that Materialistic values would not have any significant effect on religiosity. Second, considering the secularization hypothesis, (H1) Materialism negatively affects religiosity. Third, following the ‘Prosperity Gospel’, (H2) ‘materialism’ and ‘religiosity’ are positively related. In addition, (H3) ‘age’ moderates the relationship between materialism and religiosity sense among human beings. However, both materialism and religiosity are complex multidimensional constructs, and people may have a wide variety of reasons to be materialistic (irrespective of their religious traditions) or religious (regardless of their acquisition centrality). Nonetheless, by following an appropriate research design, and applying a rigorous statistical tool, such as ‘Structural Equation Modelling’ (SEM), the research hopes to provide a valuable insight of how the study of religion can address the academic problems of materialistic value-orientation. SEM is the combination of ‘factor analysis’ and ‘multiple regression analysis’ with the ability to impute relationships between unobserved constructs or the latent variables, and the benefit of having computer-intensive applications to deal with the large datasets in complex and unstructured problems. Since there is insufficient empirical evidence that shows the link between materialism and religiosity especially when applied to the transitional society chiefly due to the complex nature of context-dependent measurement considerations, the study has implications for measurement issues. In addition, to maintain itself or to survive over the long term, every religious tradition must preserve a particular set of beliefs, and, as it stands, the study may indicate whether materialism posits a real threat as it historically been considered. Finally, Bangladesh is an under-researched area and the inclusion of ‘Muslim religiosity’ in research models has been limited in the empirical investigation; therefore, our study can benefit the concerned theorists to explain the effect of the transformation of the economic institution on the religious institution.

3. Results

Individual factors for every measurement item had low variance, and covariance among the factors is allowed. The standardized regression coefficients are considered for the estimation of the pure factors since the test only loaded the targeted factors. The study did not have any specific correlation with regard to the error measurement. This fosters the formation of the model with a smaller chi-square value. Methodologically speaking, using smaller values to the chi-square and the ratio of chi-square and degree of freedom can give better estimation with respect to goodness of fit (

Ellis 1992). The values for Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (0.776) and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (Approximate chi-square = 2.650E3, df = 496 and

p < 0.001) indicate the Sampling Adequacy to the effect; the estimation consists of first-order reflective (materialistic value-orientation) and second-order formative construct (religiosity).

Results show that ‘Material Success’ (

t = 20.03) and ‘Material Happiness’ (

t = 25.47) are found to be significant (at

p < 0.001) and ‘Acquisition Centrality’ (

t = 0.324) results in being insignificant to form ‘Materialism’. In addition, internal consistency reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity of the constructs seem to be less meaningful to explain the formative construct due to the value of Average variance extracted (AVE = 0.44) and composite reliability (CR = 0.64) for Materialism Construct (

Wong 2013). The error terms of ‘Centrality’ and ‘Success’ as well as of ‘Centrality’ and ‘Happiness’ are found to be related; after drawing the co-variances, the model fit indexes support the construct (CFI = 0.905; CMIN/DF = 1.775; IFI = 0.908; RMSE = 0.043). However, the two factor constructs (Success and Happiness) seem to be more appropriate to measure the latent variable ‘materialism’ where no error terms are found to be related and the model fit shows the acceptance (CFI = 0.924; CMIN/DF = 1.808; IFI = 0.927; RMSE = 0.044); nonetheless, deleting ‘centrality’ would be unwise due to the strong theoretical and methodological support by the study of

Richins and Dawson (

1992). In addition, item C3 (the things I own aren’t all that important to me) of ‘Acquisition Centrality’ and item H3 (I wouldn’t be any happier if I owned nicer things) of ‘Material Happiness’ seem to be statistically insignificant to measure the respective constructs. Again, considering the originality of the scale, and if theoretical support is taken under consideration, all three of the constructs and all 18 of the items can be used to estimate the structural equation model of interest (

Hair et al. 1998).

Materialism construct is measured as first-order dimension and the scores are averaged for each dimension to get a single score. Please consider

Table 1 and

Table 2 for Reliability and Validity of Second-order Formative and First-order Reflective Construct.

Unlike materialism, in cases of Second-order reflective measure of religiosity construct, a systematic analysis of items and the observed construct is developed to measure the latent variable of interest. Almost all items of the three constructs (Religious Influence, Religious Involvement, and Religious Hope) of religiosity are loaded significantly above the threshold level of 0.50 on their latent variables and AVE also results above the point of 0.50 (

Bagozzi and Yi 1988) for the first-order latent constructs ‘Religious Influence’ and ‘Religious Involvement’. Although the items loading for ‘Religious Hope’ seems poor; however, if items HP1, HP5, and HP6 are discarded from the construct, it leads to an acceptable value of composite reliability (CR). The square root of latent constructs is higher than all of the correlation values of other latent constructs. The value of composite reliability (CR) of all the first-order latent constructs is more than the threshold level of 0.70 (

Bagozzi and Yi 1988). The model fulfills the requirement of convergent validity, discriminant validity, and internal consistency reliability from the theoretical ground (

Hair et al. 1998). While age is considered as a mediating variable for materialism, it also reaches a valid construct (AVE = 0.74, CR = 0.89, and Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.83). Please consider

Table 3 and

Table 4 for Factors loading and Reliability and Validity Issues for Religiosity. Please consider

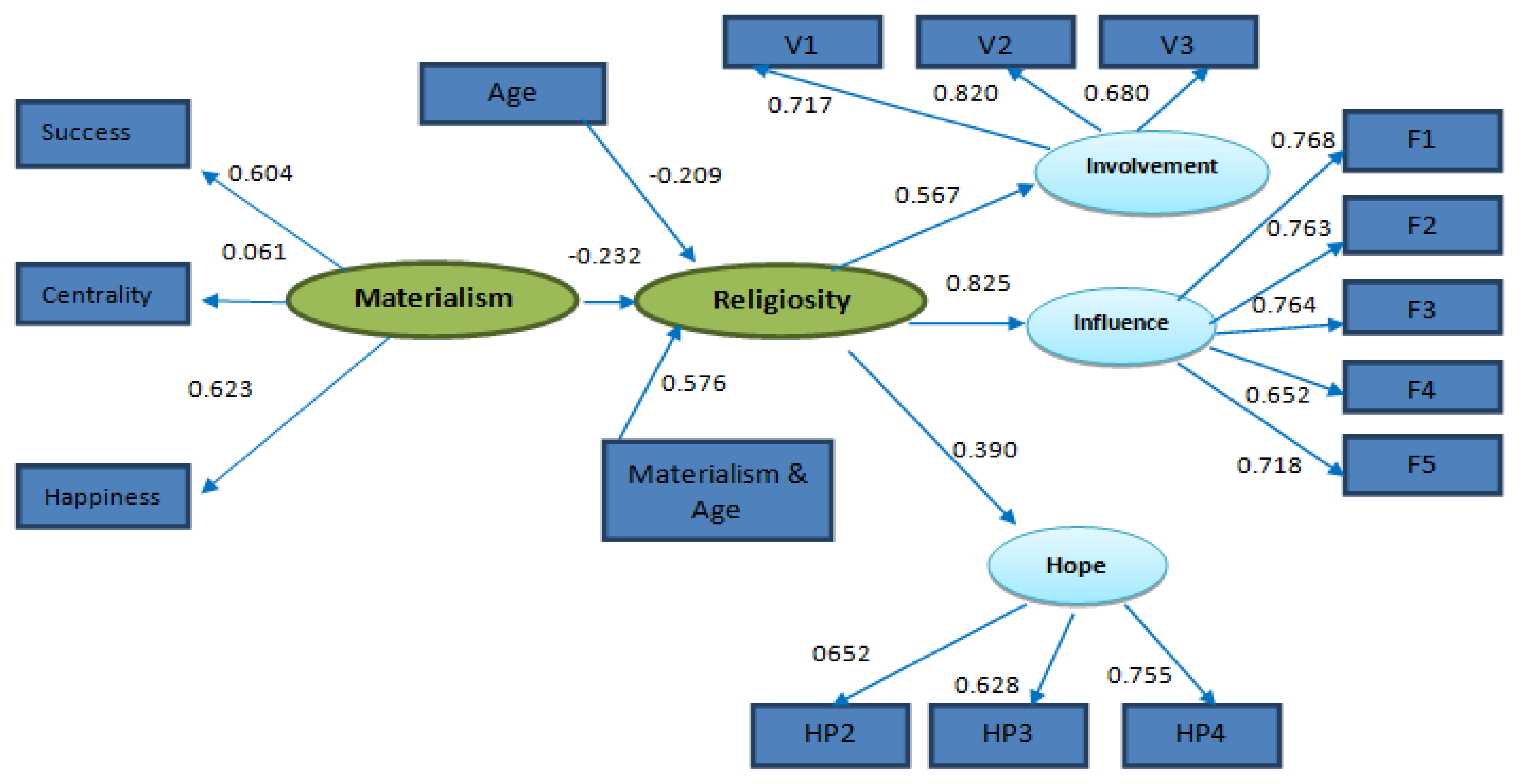

Figure 1 for values of the estimation.

SmartPLS also measures the goodness of fit (GoF) index (

Tenenhaus et al. 2005). This measure uses the geometric mean of the average communality and the average

R2 (for endogenous constructs). The cut-off values for assessing the results of the GoF analysis is reported as GoF small = 0.1; GoF medium = 0.25; of large = 0.36 (

Ali et al. 2016). We have obtained a GoF score of 0.28 that indicates that our model is medium fit with data (please consider

Table 5). However, this measurement index should be interpreted with caution such that it only explains how the survey data fits with the proposed model (

Ali et al. 2016).

From the structural model, 15% of the variation in religiosity is observed by the materialistic value-orientation and the interaction effect of materialism and age. Materialism negatively affects religiosity and found to be significant with a value of 0.23. However, only age does not have any significant effect on religiosity, however, the interaction effect of materialism and age is seen as significant with a positive indication. Hence, a complete moderating effect of age is found. This implies that the predicted hypotheses H

1 and H

3 are supported with the calculated value. Please consider

Table 6 for the result of the hypothesis testing.

4. Discussion

Bangladesh has one of the fastest growing economies in South Asia (the Asian Development Bank reports that the country’s economy grew by 7.1% in 2016 and had above 6% GDP growth for the last six consecutive years), and is experiencing rapid socio-economic transitions; therefore, the state of the materialism among people is more likely to rise. This will bring a shift in the normative values, and a changing perspective about the role of religion may occur. The results of the current study imply that when materialistic value-orientation is increased into the human mind, it has a dwindling effect on religiosity and diminishes to about one-fourth of the extent of religiousness. Both materialism and religiosity have been found to be important predictors of behavioral patterns among people. Since the study provides reliable and valid statistical estimates, materialistic value-orientation should be considered as a crucial predictor anticipating the change in the religious formation of the people of Bangladesh. The people neither trying to hold their state of religiosity strongly indicating religious revivalism is not evident, nor are they integrating materialism as part of religiosity like the prosperity theology. Although Islamic extremism is undeniable, it nonetheless has little to do with normative values of the common people and is more closely related to political gains. In addition, more work needs to be carried out on how materialism and religiosity affect the social values of a person in general. A cohort study may address the situation properly and explain the state of the affairs from one point of time to another. The present study also left out a range of demographic variables that may contribute as mediating variables. Investigating the role of age alone in influencing the level of materialism and religiosity is yet to be conclusive. Future works should investigate the effect that the additional variables such as education and occupation have with regard to these constructs. As it currently stands, the results of the present research lead to developing three propositions: first, the secularization thesis can be used as a valid explanation tool to address the shift of the religiosity that is resulting due to economic progression. Second, since Materialistic value-orientation has an effect on religiousness, people’s values may change, whether positively or negatively, and we can anticipate some societal transformations. Third, the age of the respondents plays a crucial role in materialism and religiosity. Fourth, for Bangladesh, as a transitional Muslim country, the value of the religiosity may deviate from the state, and adapt materialism if the economic progression continues and the size of the middle class rises.

First, the people of the society that is facing a rapid transition are often less constrained by traditional normative values linked to religiosity and more prone to personally embraced materialistic morals (

Durkheim and Swain 1916). The economic growth of a country, on one hand, reflected through the spending habits of the citizens (

Griffin et al. 2004), while the increasing rates of consumerism reflect materialistic value-orientation. The acquisition of material possessions is an imperative element in the pursuit of the good life to the persons endowed with materialistic values (

Richins 1994). One prominent notion concerning the economic development is that, with the progression of the society through modernization and rationalization, religion loses its influence in all facets of convivial life and governance (

Norris and Inglehart 2004). It is also said that “to be secular means to be modern, and therefore by implication, to be religious means not yet fully modern” (

Casanova 2011, p. 59). Second, Islamic countries and Muslim Societies often form a religion-based economic system, where the pursuit of material goods and capital accumulation are regarded to a large extent as negative personality traits. Religious practice has been shown to have a positive effect on the social wellbeing of people. It has a noteworthy impact on the personality and the advancement of the juridical and institutional frame of a society and acts as a principal determinant of the economic development (

Hergueux 2007). Therefore, changing pattern of religiosity leads to the transformation of other social institutions. Third, some researchers found that materialism increases from middle childhood to early adolescence and decreases from early to late adolescence (

Chaplin and John 2007). Age distinctions are mediated by shifts in self-esteem occurring from middle childhood through adolescence, and excessive self-esteem decreases expressions of materialism, which is unusual among adolescents—while others argue that materialism goes down with age and follows a curvilinear trajectory across the lifespan, with the lowest levels at middle age and higher levels before and after that (

Jaspers and Pieters 2016). It is also argued that ‘acquisition centrality’ and possession-defined success were higher at younger and older ages (

Jaspers and Pieters 2016). Independent of these age effects, older birth cohorts were oriented more towards possession-defined success, since younger birth cohorts were oriented more towards ‘acquisition centrality’. Similar findings are suggested by others, indicating that life remains simple in terms of material possessions in childhood, and it becomes most perplexed in old age (removed for pee review). Similarly, ‘possession essentiality’ remains comparatively low during the childhood and adolescence and slightly goes upward during when people start in early adulthood. This remains steady during early and middle adulthood and gets an abrupt upward turn after that period of life. The ‘possession essentiality’ tends to grow up at the old age.

Fourth, a changing pattern of religiosity is visible at least among the middle-class and a thin line separates the ‘Bengali values’ and ‘modern consumer culture’ of Bangladesh (

Bielefeldt 2015). From 2015, Bangladesh is a lower-middle-income country, with an average annual income of

$1046 to

$4125 (

WB Update Says 10 Countries Move Up in Income Bracket 2015). Each year at least 2 million Bangladeshis join the middle-class as affluent consumers (

Munir et al. 2015). This rising middle class in the country is optimistic about the future economic growth of the country and places higher value on international brands (

Rashid 2015). Religiosity is also among the central cultural traits of Bangladesh throughout the history (

Bielefeldt 2015). The religious demography of Bangladesh is broadly Islamic; nonetheless, the successful coexistence of the various religious communities in Bangladesh is traceable (

Willmott 2014). While intolerance and extremism have been on the rise worldwide, the issues are not seen as fitting the predominant culture of harmonious coexistence between different religions in Bangladesh (

Bielefeldt 2015). However, the recent demographic changes also posit a serious challenge to the harmonious coexistence of people of various religious backgrounds (

Howell 1993). However, the religious polarization is an emerging nationwide discussion, and very few systematic studies investigate the changing nature of Bangladesh’s society (

Yasmin 2013). Most of the citizens of Bangladesh report that religion plays a leading role in their lives (

BANGLADESH 2015 International Religious Freedom Report 2015). Similar findings are suggested by Gallup surveys, indicating that hundreds of nations having a low per-capita GDP (below

$5000), and are found to be the most religious countries as well (

Crabtree 2010). Due to the results of the current socioeconomic diversity, the people of Bangladesh have developed a wide range of perspectives with regard to religion. For example, while the country has an increasing number of secular bloggers and writers that criticize the religious doctrines of Bangladesh, the country also has fundamentalists that go to extremes to stop them (

Hammer 2015). International cooperation, labor migration, international politics and refugee crises have a huge impact on Bangladesh (

McAndrew and Voas 2011). Bangladesh sends migrant workers to other neighboring Middle Eastern countries. Upon their return back home, the workers return with a stricter version of Islam that is not consistent with the tolerant version of Bangladeshi culture (

Yasmin 2013). This creates a ripple effect since the political parties in the countries are facing intensifying demands to uphold the Islamic interests above other religious considerations (

Bouissou 2013). Agreeing to those demands results in a paradoxical situation. In addition, the tensions that are caused by the foreign relations could have negative effects on how the communities interact in the country. Finally, since people with more materialistic value-orientation are less religious, the economic progress perhaps will post a threat to the religiousness of the people.

The present study perhaps can facilitate the methodological expansion of measuring religiosity and address the gap of interpreting the theories of religions. Previous studies relate ‘Emotional Connection’, ‘Subjective Well-Being’, ‘Happiness’ or ‘Life Satisfaction’ with that of ‘Materialism’ and ‘Religiosity’. In consumer research, the effects of consumer materialistic attitudes (a secular value) and religiosity (a sacred value) on subjective well-being are being addressed (

Barbera and Gürhan-Canli 1997). They found that the subjective well-being of the consumers is negatively related to some aspects of the materialism. Studies in business, however, are often less clear to define the direct relationship between materialism and religiosity. Some argue that materialism has an indirect effect on life satisfaction where religiosity and stress play a mediating role (

Baker et al. 2013). In addition, people’s material accumulation has no association with happiness; people consider religiosity as their identity, but not their activities (

Swinyard et al. 2001). Research on the

Umrah participants of Iran shows that Muslim religiosity is positively related to positive emotion, whereas materialism has a negative effect. (

Taheri 2016). People with explicit Islamist dispositions are found to be more likely to purchase products or avail services that could reflect status even at the expense of debts (

Yeniaras 2016). Where there are a number of studies considering materialism with many variables such as subjective well-being, nonetheless ‘Religiosity’ has not been addressed in academic studies. While some researchers (

McCleary and Barro 2006a,

2006b;

Barro and McCleary 2014) show how religiosity is influencing the formation of economic behavior by influencing education, value attributed to time, life expectancy, and urbanization, and hardly any research shows the opposite. Therefore, it can be argued that, although the researchers have made significant strides as far as the development of a clearer understanding with regard to the link between materialism, religiosity and subjective well-being (

Chang and Arkin 2002;

Karabati and Cemalcilar 2010b;

Żemojtel-Piotrowska et al. 2013;

Manolis and Roberts 2012), nonetheless what happens in transitional societies, particularly in Muslim countries, is hardly addressed. By addressing the gap, the study concludes that materialistic value orientation has a negative effect on the religiosity of the Muslims in Bangladesh.