Unpacking Donor Retention: Individual Monetary Giving to U.S.-Based Christian Faith-Related, International Nongovernmental Organizations

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Review of the Literature

2.1. Christianity and International Giving in the U.S.

2.2. Christian Faith-Related NGOs, Managing Identities

- (1)

- Christianity is explicit in their origins or history, but may not be explicit currently;

- (2)

- staff are not required to affirm Christianity, but senior staff often do;

- (3)

- programs and services are not entirely Christian, but Christian content may be available if desired; and,

- (4)

- there is a mix of private and secular funding.

2.3. Donor Retention as One Expression of Loyalty to an NGO

2.4. Repeat Donor Intention as Expressed by the Donors Themselves

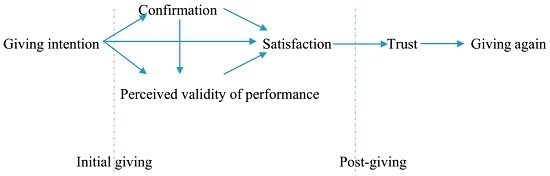

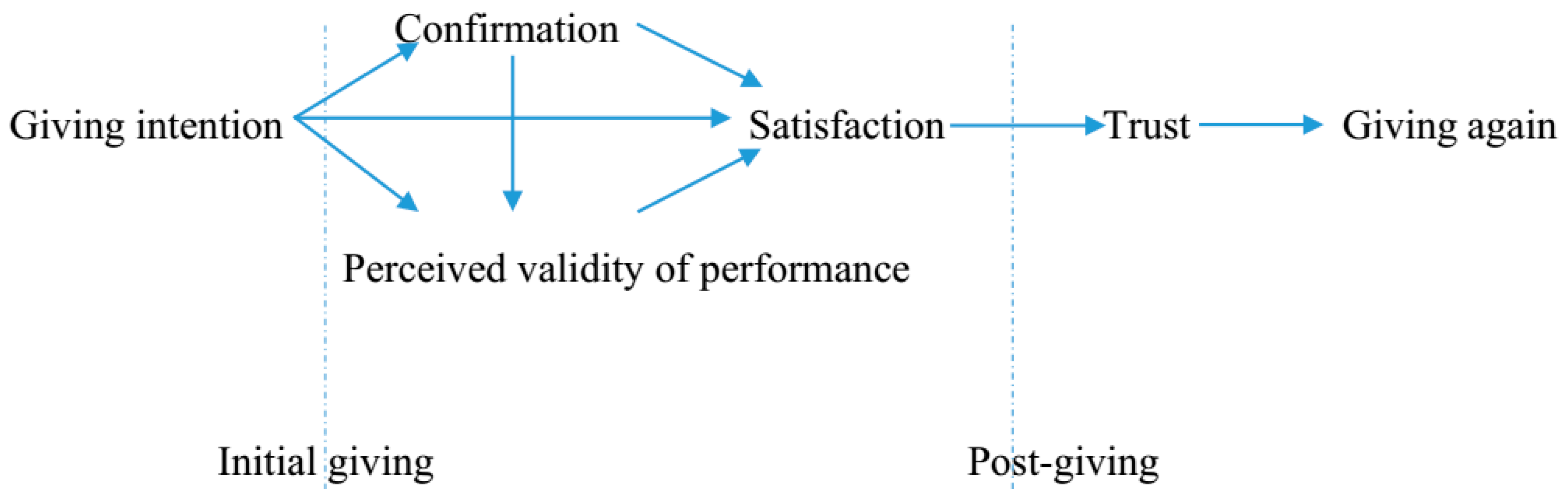

3. Proposition Development: Christian Faith-Related INGOs and Individual Donors’ Evaluation of Retention

Level of Donor Confirmation and Satisfaction

4. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- David Lewis. “Theorising the organisation and management of non-governmental development organisations: Towards a composite approach.” Public Management Review 5 (2003): 325–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrian Sargeant, and Lucy Woodliffe. “Building donor loyalty: The antecedents and role of commitment in the context of charity giving.” Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing 18 (2007): 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laura C. Thaut. “The role of faith in Christian faith-based humanitarian agencies: Constructing the taxonomy.” Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 20 (2009): 319–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierk Herzer, and Peter Nunnenkamp. “Private Donations, Government Grants, Commercial Activities, and Fundraising: Cointegration and Causality for NGOs in International Development Cooperation.” Kiel Working Papers 46 (2013): 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giving USA. “Giving USA 2016: The Annual Report on Philanthropy for the Year 2015.” Available online: https://givingusa.org/product/2016-digital-package/ (accessed on 10 October 2016).

- Giving USA. “Giving USA 2015: The Annual Report on Philanthropy for the Year 2014.” Available online: https://givingusa.org/product/giving-usa-2015-the-annual-report-on-philanthropy-for-the-year-2014-digital-package-pre-sale/ (accessed on 10 October 2016).

- Global Impact. “Assessment of U.S. Giving to International Causes.” Available online: http://charity.org/sites/default/files/userfiles/pdfs/Assessment%20of%20US%20Giving%20to%20International%20Causes%20FINAL.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2016).

- Amy F. Butcher. “Giving Report Shows Growth, But Not for Everyone.” Nonprofit Quarterly, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Michael Barnett, and Janice Stein. Sacred Aid: Faith and Humanitarianism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gerard Clarke. “Faith matters: Faith-based organisations, civil society and international development.” Journal of International Development 18 (2006): 835–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firoze Manji, and Carl O’Coill. “The missionary position: NGOs and development in Africa.” International Affairs 78 (2002): 567–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert Wuthnow. Saving America?: Faith-based Services and the Future of Civil Society. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- The Winthrop Society. “A Model of of Christian Charity: By Governor John Winthrop, 1630.” Available online: http://winthropsociety.com/doc_charity.php (accessed on 3 June 2016).

- Kathleen D. McCarthy. American Creed: Philanthropy and the Rise of Civil Society, 1700–1865. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Samuel P. Huntington. Who Are We?: The Challenges to America's National Identity. New York, London, Toronto and Sydney: Simon and Schuster, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Julie Hearn. “The ‘invisible’ NGO: US evangelical missions in Kenya.” Journal of Religion in Africa 32 (2002): 32–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaret Harris. Organizing God’s Work: Challenges for Churches and Synagogues. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- James Leiby. “Charity organization reconsidered.” Social Service Review 58 (1984): 523–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecelia Lynch. “Acting on belief: Christian perspectives on suffering and violence.” Ethics and International Affairs 14 (2000): 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilde Nielssen, Inger Marie Okkenhaug, and Karina Hestad-Skeie. “Introduction.” In Protestant Missions and Local Encounters in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries: Unto the Ends of the World. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2011, pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Julia Berger. “Religious nongovernmental organizations: An exploratory analysis.” Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 14 (2003): 15–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachel M. McCleary, and Robert J. Barro. “Private voluntary organizations engaged in international assistance, 1939–2004.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 37 (2008): 512–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- José Casanova. Public Religion in the Modern World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Adil Najam. “NGO accountability: A conceptual framework.” Development Policy Review 14 (1996): 339–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlo Benedetti. “Islamic and Christian inspired relief NGOs: Between tactical collaboration and strategic diffidence? ” Journal of International Development 18 (2006): 849–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher P. Scheitle. Beyond the Congregation: The World of Christian Nonprofits. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gerard Clarke, and Michael Jennings. “Introduction.” In Development, Civil Society and Faith-Based Organizations: Bridging the Sacred and the Secular. Edited by Gerald D. Clarke and Michael D. Jennings. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ramya Ramanath. “Capacity for public service delivery: A cross-case analysis of ten small faith-related non-profit organisations.” Voluntary Sector Review 5 (2014): 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronald J. Sider, and Heidi Rolland Unruh. “Typology of religious characteristics of social service and educational organizations and programs.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 33 (2004): 109–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eric Werker, and Faisal Z. Ahmed. “What do nongovernmental organizations do? ” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 22 (2008): 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marc Lindenberg, and Coralie Bryant. Going Global: Transforming Relief and Development NGOs. Bloomfield: Kumarian Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- David L. Brown, Alnoor Ebrahim, and Srilatha Batliwala. “Governing international advocacy NGOs.” World Development 40 (2012): 1098–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helen Rose Ebaugh, Paula F. Pipes., Janet Saltzman Chafetz, and Martha Daniels. “Where’s the religion? Distinguishing faith-based from secular social service agencies.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 42 (2003): 411–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abby Stoddard. “Humanitarian NGOs: Challenges and trends.” London: Humanitarian Policy Group, Overseas Development Institute, 2003, Available online: https://www.odi.org/resources/docs/349.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2016).

- Ted Yu Shen Chen. “Habitat for Humanity’s post-tsunami housing reconstruction approaches in Sri Lanka.” International Journal of Mass Emergencies & Disasters 33 (2015): 96–116. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew McGregor. “Geographies of religion and development: Rebuilding sacred spaces in Aceh, Indonesia, after the tsunami.” Environment and Planning A 42 (2010): 729–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James R. Vanderwoerd. “How faith-based social service organizations manage secular pressures associated with government funding.” Nonprofit Management & Leadership 14 (2004): 239–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Water Wymer, and Sharyn Rundle-Thiele. “Supporter loyalty conceptualization, measurement, and outcomes.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 45 (2016): 172–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norm O’Reilly, Steven Ayer, Ann Pegoraro, Bridget Leonard, and Sharyn Rundle-Thiele. “Toward an understanding of donor loyalty: Demographics, personality, persuasion, and revenue.” Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing 24 (2012): 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caryl E. Rusbult, and Daniel Farrell. “A longitudinal test of the investment model.” Journal of Applied Psychology 68 (1983): 429–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James D. Werbel, and Sam Gould. “A comparison of the relationship of commitment to turnover in recent hires and tenured employees.” Journal of Applied Psychology 69 (1984): 687–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles A. O’Reilly, and David F. Caldwell. “Job choice: The impact of intrinsic and extrinsic factors on subsequent satisfaction and commitment.” Journal of Applied Psychology 65 (1980): 559–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard T Mowday, Lyman M. Porter, and Richard M. Steers. Organizational Linkage: The Psychology of Commitment, Absenteeism and Turnover. New York: Academic Press, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Harold L. Angle, and James L. Perry. “An empirical assessment of organizational commitment and organizational effectiveness.” Administrative Science Quarterly 26 (1981): 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helen Bussell, and Deborah Forbes. “Developing relationship marketing in the voluntary sector.” Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing 15 (2006): 151–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adrian Sargeant. “Relationship fundraising: How to keep donors loyal.” Nonprofit Management and Leadership 12 (2001): 177–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roger Bennett, and Rehnuma Ali-Choudhury. “Internationalisation of British fundraising charities: A two-phase empirical study.” International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 15 (2010): 28–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julia Naskrent, and Philipp Siebelt. “The influence of commitment, trust, satisfaction, and involvement on donor retention.” Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 22 (2011): 757–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrian Sargeant, and Shang Jen. “Growing Philanthropy in the United States: A Report on the June 2011 Washington, D.C. Growing Philanthropy Summit.” 2011. Available online: http://www.simonejoyaux.com/downloads/growingphilanthropyreport_final.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2016).

- Ken Burnett. Relationship Fundraising: A Donor Based Approach to the Business of Raising Money. San Francisco: Jossey Bass, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Yi-Hui Huang. “OPRA: A cross-cultural, multiple-item scale for measuring organisation-public relationships.” Journal of Public Relations Research 13 (2001): 61–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun-ju Flora Hung. “Toward a normative theory of relationship management.” Available online: http://www.instituteforpr.org/normative-theory-relationship-management/ (accessed on 3 January 2016).

- Sally Shaw, and Justine B. Allen. “We Actually Trust the Community: Examining the dynamics of a nonprofit funding relationship in New Zealand.” Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 17 (2006): 211–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Fundraising Professionals. “Fundraising Effectiveness Survey Report.” 2012. Available online: http://www.afpnet.org/files/ContentDocuments/FEP2012Report.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2015).

- Adrian Sargeant. “Donor retention: What do we know and what can we do about it? ” 2008. Available online: https://afpidaho.afpnet.org/files/ContentDocuments/Donor_Retention_What_Do_We_Know.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2015).

- Dennis B. Arnett, Steve D. German., and Shelby D. Hunt. “The identity salience model of relationship marketing success: The case of nonprofit marketing.” Journal of Marketing 67 (2003): 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namkee G. Choi, and Diana M. DiNitto. “Predictors of time volunteering, religious giving, and secular giving: Implications for nonprofit organizations.” Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare 39 (2012): 93–120. [Google Scholar]

- Mark Chaves. “Financing American religion.” In Financing American Religion. Edited by Mark Chaves. Walnut Cree: AltaMira Press, 1999, pp. 169–88. [Google Scholar]

- Mark Chaves, and Sharon L. Miller, eds. Financing American Religion. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press, 1999.

- John M. Mulder. “Faith and money: Theological reflections on financial American religion.” In Financing American Religion. Edited by Mark Chaves. Walnut Cree: AltaMIra Press, 1999, pp. 157–68. [Google Scholar]

- Debra A. Laverie, and Dennis B. Arnett. “Factors affecting fan attendance: The influence of identity salience and satisfaction.” Journal of Leisure Research 32 (2000): 225–46. [Google Scholar]

- Simon McGrath. “Giving donors good reason to give again.” Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 2 (1997): 125–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monica Langley. “Mr. Rose gives away millions in donations, not a cent of control.” Wall Street Journal, 1998, A1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Howard P. Tuckman. “Competition, commercialization, and the evolution of nonprofit organizational structures.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 17 (1998): 175–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathleen S. Kelly. Fund Raising and Public Relations: A Critical Analysis. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas H. Jeavons. “The vitality and independence of religious organizations.” Society 40 (2003): 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amber Nathan, and Leslie Hallam. “A qualitative investigation into the donor lapsing experience.” International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 14 (2009): 317–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbara L. Ciconte, and Jeanne Jacob. Fundraising Basics: A Complete Guide, 3rd ed. Boston: Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Farnoosh Khodakarami, Andrew J. Peterson, and Rajkumar Venkatesan. “Developing donor relationships: The role of the breadth of giving.” Journal of Marketing 79 (2015): 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardion Beldad, Babiche Snip, and Joris van Hoof. “Generosity the second time around: Determinants of individuals’ repeat donation intention.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 43 (2014): 144–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jundong Hou, Chi Zhang, and Robert Allen King. “Understanding the dynamics of the individual donor’s trust damage in the philanthropic sector.” Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daryl J. Bem. “Self-perception theory.” Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 6 (1972): 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ken J. Rotenberg. “The socialisation of trust: Parents’ and children’s interpersonal trust.” International Journal of Behavioral Development 18 (1995): 713–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roger C. Mayer, James H. Davis, and F. David Schoorman. “An integrative model of organizational trust.” Academy of Management Review 20 (1995): 709–34. [Google Scholar]

- Sander Van der Linden. “Charitable intent: A moral or social construct? A revised theory of planned behavior model.” Current Psychology 30 (2011): 355–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher J. Einolf. “The link between religion and helping others: The role of values, ideas, and language.” Sociology of Religion 72 (2011): 435–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karen S. Cook, and Russell Hardin. Norms of Cooperativeness and Networks of Trust. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Edward J. Lawler, and Jeong Koo Yoon. “Power and the emergence of commitment behavior in negotiated exchange.” American Sociological Review 58 (1993): 465–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debra Z. Basil, Nancy M. Ridgway, and Michael D. Basil. “Guilt appeals: The mediating effect of responsibility.” Psychology & Marketing 23 (2006): 1035–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roger Bennett, and Anna Barkensjo. “Relationship quality, relationship marketing, and client perceptions of the levels of service quality of charitable organisations.” International Journal of Service Industry Management 16 (2005): 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel Wedel, and Wagner A. Kamakura. Market Segmentation: Conceptual and Methodological Foundations. Norwell: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Elizabeth J. Durango-Cohen, Ramón L. Torres, and Pablo L. Durango-Cohen. “Donor Segmentation: When Summary Statistics Don’t Tell the Whole Story.” Journal of Interactive Marketing 27 (2013): 172–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catholic Relief Services. “About Catholic Relief Services.” 2016. Available online: http://www.crs.org/about (accessed on 3 June 2016).

- Catholic Relief Services. “Catholic Relief Services: United States Conference of Catholic Bishops.” 2004. Available online: http://www.crs.org/sites/default/files/2005_financials.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2016).

- Anne Vestergaard. “Distance and Suffering: Humanitarian Discourse in the age of Mediatization.” Ph.D. Thesis, Copenhagen Business School, Frederiksberg, Denmark, 4 July 2016. Available online: http://www.lse.ac.uk/media@lse/study/pdf/ChouliarakiLSEPublicLectureDistantSuffering.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Jesse D. Lecy, Hans Peter Schmitz, and Haley Swedlund. “Non-Governmental and not-for-profit organizational effectiveness: A modern synthesis.” Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 23 (2011): 434–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepard Forman, and Abby Stoddard. “International assistance.” In The State of Nonprofit America. Edited by Lester M. Salomon. Washington: Brookings Institution Press, 2002, pp. 240–74. [Google Scholar]

- May-May Meijer. “The effects of charity reputation on charitable giving.” Corporate Reputation Review 12 (2009): 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jane E. Dutton, Janet M. Dukerich, and Celia V. Harquail. “Organizational images and member identification.” Administrative Science Quarterly 39 (1994): 239–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beth Breeze. “How donors choose charities: The role of personal taste and experiences in giving decisions.” Voluntary Sector Review 4 (2013): 165–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisa Austen Jones. “Incentives: Making the most of incentives budgets—Market trends are determining how firms are rewarding staff.” Marketing 107 (2002): 29–31. [Google Scholar]

- Michael J. Worth. New Strategies for Educational Fund Raising. Westport: Praeger Publishers, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Altaf Merchant, John B. Ford, and Adrian Sargeant. “‘Don’t forget to say thank you’: The effect of an acknowledgement on donor relationships.” Journal of Marketing Management 26 (2010): 593–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnoor S. Ebrahim, and V. Kasturi Rangan. “The limits of nonprofit impact: A contingency framework for measuring social performance.” Harvard Business School, General Management Unit Working Paper No. 10–099; Boston, MA, USA: Harvard Business School, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Adrian Sargeant, and Stephen Lee. “Trust and relationship commitment in the United Kingdom voluntary sector: Determinants of donor behavior.” Psychology & Marketing 21 (2004): 613–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natalie J. Allen, and John P. Meyer. “The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization.” Journal of Occupational Psychology 63 (1990): 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilie Chouliaraki. “Post-humanitarianism Humanitarian communication beyond a politics of pity.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 13 (2010): 107–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mirca Madianou. “Humanitarian campaigns in social media: Network architectures and polymedia events.” Journalism Studies 14 (2013): 249–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1In this article, I view INGOs as a sub-set of NGOs i.e., NGOs that are based in and receive funds from high-income countries, located primarily in the global North but are working to address the needs of those in one or more low-income countries, largely in the global South. NGOs can be defined in a variety of ways, but are often defined by what they are not (i.e., not government or business) rather than what they are. The question of what NGOs are, is widely debated. Lewis ([1], p. 327) argues that there are two ways in which NGOs are distinct—their identity as a subset of third sector organizations that do not make a profit and derive their authority independent of a political process and also that they engage in emergency relief, service delivery and/or policy and rights advocacy. I use the term nongovernmental organization instead of the more US-specific term for this same breed of organizations, namely nonprofit organization (NPO). I do so in order to avoid an overload of terms and abbreviations in this article. I recognize that US-based NGOs, whether international in their scope of activities or not, are referred to as nonprofit organizations. When I am certain that the concerned author is referring to an NGO that is headquartered in a global North country but focuses its operations on the needs—be it emergency relief, service delivery and/or rights-based and advocacy interventions—in the global South, then I use the term INGO.

- 2In Herzer and Nunnenkamp’s [4] study, these NGOs (referred to as Private Voluntary Organizations) are those registered with the US Agency for International Development (USAID) and do not therefore include the full sample of US-based NGOs engaged in international affairs (see footnote 3). To qualify for registration with USAID, NGOs are required to fulfil a list of several conditions including the following: have to be US-based, solicit cash contributions from the US general public, conduct overseas program activities consistent with the general purposes of the US Foreign Assistance Act and/or Public Law 480, exempt from federal income taxes under section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code, incorporated for no less than 18 months and provide financial statements to the public upon request. This registration is necessary to compete for specific funding categories such as development and humanitarian assistance grants.

- 3Giving USA’s [5] estimate of giving to the international affairs subsectors includes giving to organizations working in international aid, development, or relief; those that promote international understanding; and organizations working on international peace and security issues. It also includes research institutes devoted to foreign policy and analysis, as well as organizations working in the domain of international human rights.

- 4Giving USA [6] attributed the decline in individual giving to international affairs to the non-occurrence of any major international natural disaster in 2014. In 2013, Global Impact [7] ascribed a decline in individual giving to international causes to economic troubles in the US and domestic natural disasters that caused individual donors to lessen their contributions to the international sector.

- 5Identity salience is a concept grounded in identity theory. According to Arnett, German & Hunt ([56], p. 89), identity salience posits that people have several "identities," that is, self-conceptions or self-definitions in their lives. These identities are arranged hierarchically and salient identities, according to identity theory, are more likely to affect behavior than those that are less important. Therefore, increasing the salience of NGO-related identity refers to increasing the importance of the NGO in defining the identity of the donor.

© 2016 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramanath, R. Unpacking Donor Retention: Individual Monetary Giving to U.S.-Based Christian Faith-Related, International Nongovernmental Organizations. Religions 2016, 7, 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7110133

Ramanath R. Unpacking Donor Retention: Individual Monetary Giving to U.S.-Based Christian Faith-Related, International Nongovernmental Organizations. Religions. 2016; 7(11):133. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7110133

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamanath, Ramya. 2016. "Unpacking Donor Retention: Individual Monetary Giving to U.S.-Based Christian Faith-Related, International Nongovernmental Organizations" Religions 7, no. 11: 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7110133