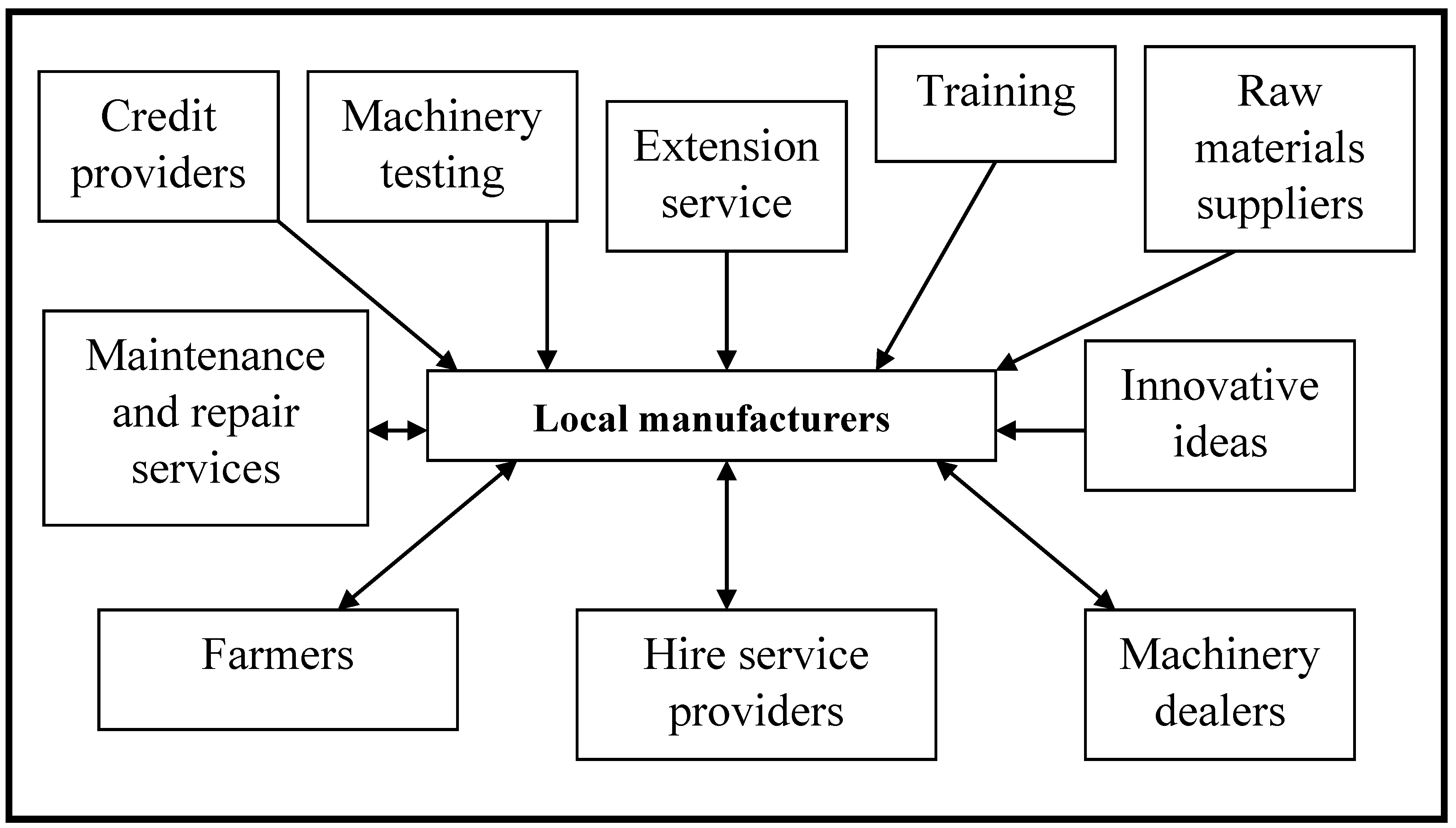

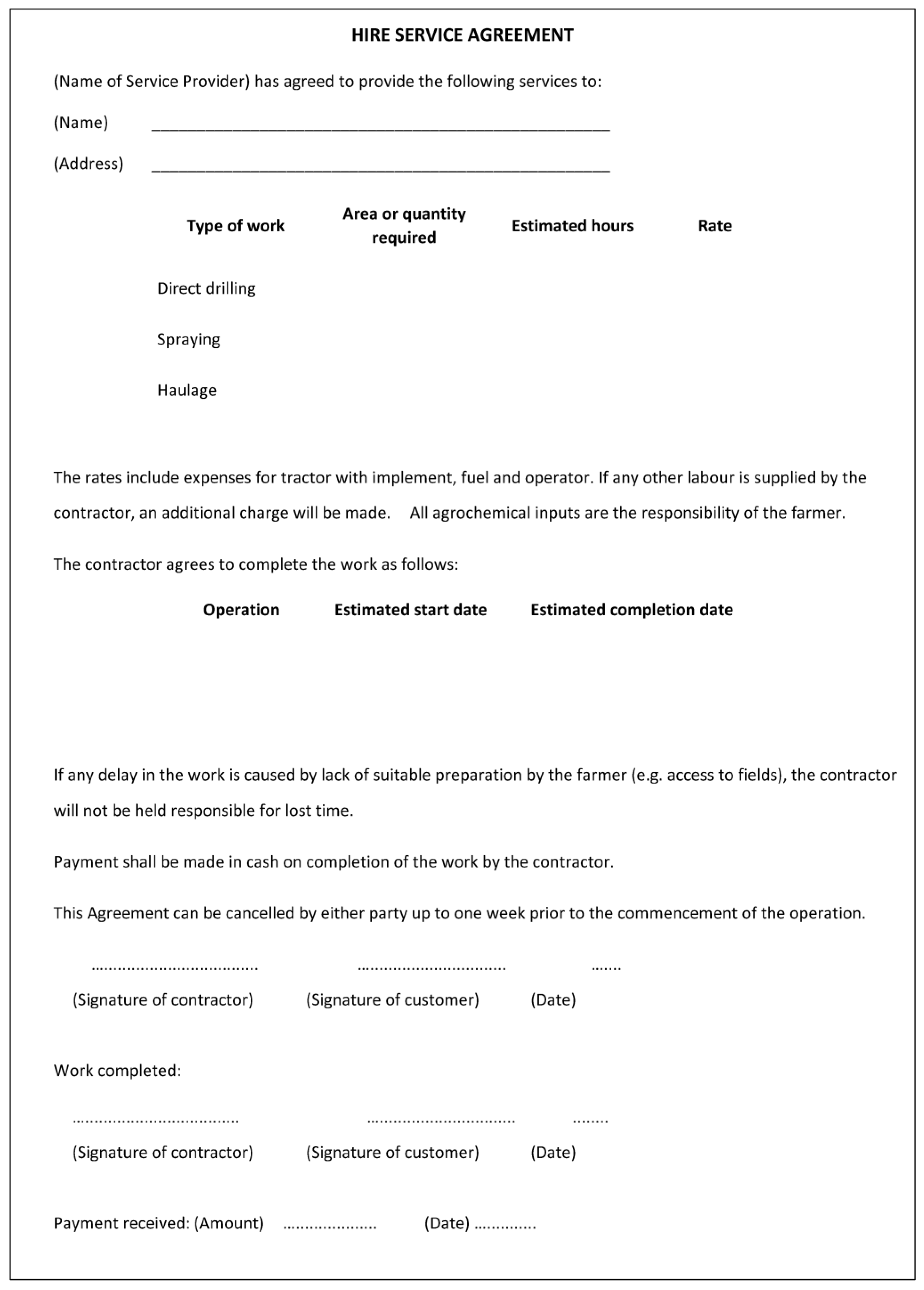

Armed with details gathered during market research and a good knowledge of available equipment, the next step for a prospective hire service provider is to make a plan. By this stage, the farmer should be aware of what demand for services exists in the area he/she proposes to operate in and who the potential clients are. He (all references to gender represent both men and women) must have established what time-windows exist to undertake certain tasks and how these are spread throughout the year. Now, he needs to make a plan to find out if operating a CA hire service can provide him with a profitable business opportunity.

2.3.1. Estimating Costs

The key question when considering a new business enterprise is: “Will it make a profit”? Profit is what is left for the farmer to use after all costs have been met from the revenue generated in a year. Therefore, what are the costs of operating a machinery hire service?

The figure that will first come to mind will be the purchase price of the equipment that is going to be used. Although this is going to be a critical figure for the farmer as he will have to raise enough to buy what he needs, it is not, of course, the annual cost of owning the equipment. The purchase price is spread over the number of years the equipment is expected to last, and the annual share of the initial cost is known as depreciation.

There are other costs involved in owning and operating machinery. You have to look after it: cleaning, sharpening, lubricating and repairing it if something breaks. You need to provide adequate shelter to protect it from the weather. Engine-driven equipment requires fuel; tractors may require a road licence; and some items need to be insured against theft and fire. You may find you need to employ extra labour to operate or repair machinery, and if you borrow money, there will be interest to pay.

Some of these costs remain fixed whether you use the machinery a lot or a little; others, such as fuel or repair bills, increase as the amount of work done increases. Spreading the fixed costs over as many hours worked as possible will clearly reduce the unit cost per hour.

2.3.2. Setting Hire Charges

In order for a service provider to know how much he can charge someone for no-till seeding, transporting their crops or undertaking any other task such as weed control or harvesting, he has to work out how much it costs to own and operate his equipment on an hourly basis.

A first, and sometimes challenging, concept to get across is how to estimate the realistic output of a tractor-implement (or draught animal-implement) combination. Details of the procedures can be found in FAO’s technical bulletin on testing agricultural machinery [

16], and the following is a brief overview.

Machine and field capacity: The power of the tractor’s engine, as well as the tractor’s weight determine its performance. Knowing the work capacity of a particular machine or tractor/implement combination is essential in determining its field capacity and to estimate its revenue earning potential. The field capacity of a farm machine is measured in hectares per hour. It is used to calculate the total number of tractors, implements and machines needed, as well as the operators required, along with the total number of hectares to be covered. Field capacities are also required for scheduling field operations on a daily, monthly and yearly basis. As an example, let us take a tractor-mounted direct planter of 3 m working width travelling at 5 km/h (the use of SI (Système international) units is often not appropriate for these kinds of field calculations).

Field efficiency (measured in percentage terms): This is the actual rate of work achieved divided by the theoretical maximum rate of work (field capacity). Its value is determined by the actual time the machine works productively. Small, irregularly-shaped fields lead to low machine field efficiency because the machine spends a lot of time turning and thus not working productively.

Table 1 gives some indication of field efficiencies that may be achieved in practice. Actual field efficiencies achieved by a hire service, however, depend on many factors, and maximizing efficiency must always be at the forefront of management thinking.

Taking the example of the direct planter above and assuming a field efficiency of 65%, the actual work-rate is given by:

Overall machine efficiency: This is of critical importance for the profitability of a service provision business and needs to be understood by service provision managers. It is made up of four components: (i) field efficiency as explained above; (ii) non-productive travel time; (iii) down-time caused by lack of work or bad weather; and (iv) down-time caused by service or repairs.

Taking all of these factors into consideration will give a realistic estimate of the amount of work that can be expected of a machine in any given situation.

The next thing to do is work out the annual costs of simply owning the machinery, i.e., the fixed costs. A calculation might be set out as in

Table 2 (details of the methods of calculation can be found in [

17]).

Then, the farmer will need to estimate how many hours of work he expects to be able to do in a typical season. If the estimate is 200 h, the fixed costs per hour will be 7156/200, which equals

$35.78. The next step is to estimate the variable costs for this amount of work (

Table 3).

Using these figures, the variable costs per hour are $16.68, and the total costs per hour add up to $52.46. This means that if it takes four hours to plant one hectare, the farmer needs an income of at least $209.84 per hectare just to cover his machinery costs. If, however, he can do 400 h of work, fixed costs would reduce to $17.89 per hour. The total variable costs would double as a result of the extra hours worked, but the rate per hour would remain the same at $16.68, provided the farmer continued to do all of the work himself. Therefore, the overall cost of the machinery would reduce to $34.57 per hour.

Now, an income of $138.28 will cover the basic cost of planting, if it takes four hours to complete. Of course, the farmer will not wish to merely cover his costs, but to make a profit, as well. Therefore, he might charge someone $160 per hectare for planting their land, which is a mark-up of just over 15%.

These example calculations illustrate the importance of obtaining sufficient work to cover costs and keep the price the farmer needs to charge down to a competitive level. It shows how important market research is before starting up a mechanization hire service.