Studies on Modulation of Gut Microbiota by Wine Polyphenols: From Isolated Cultures to Omic Approaches

Abstract

:1. Introduction

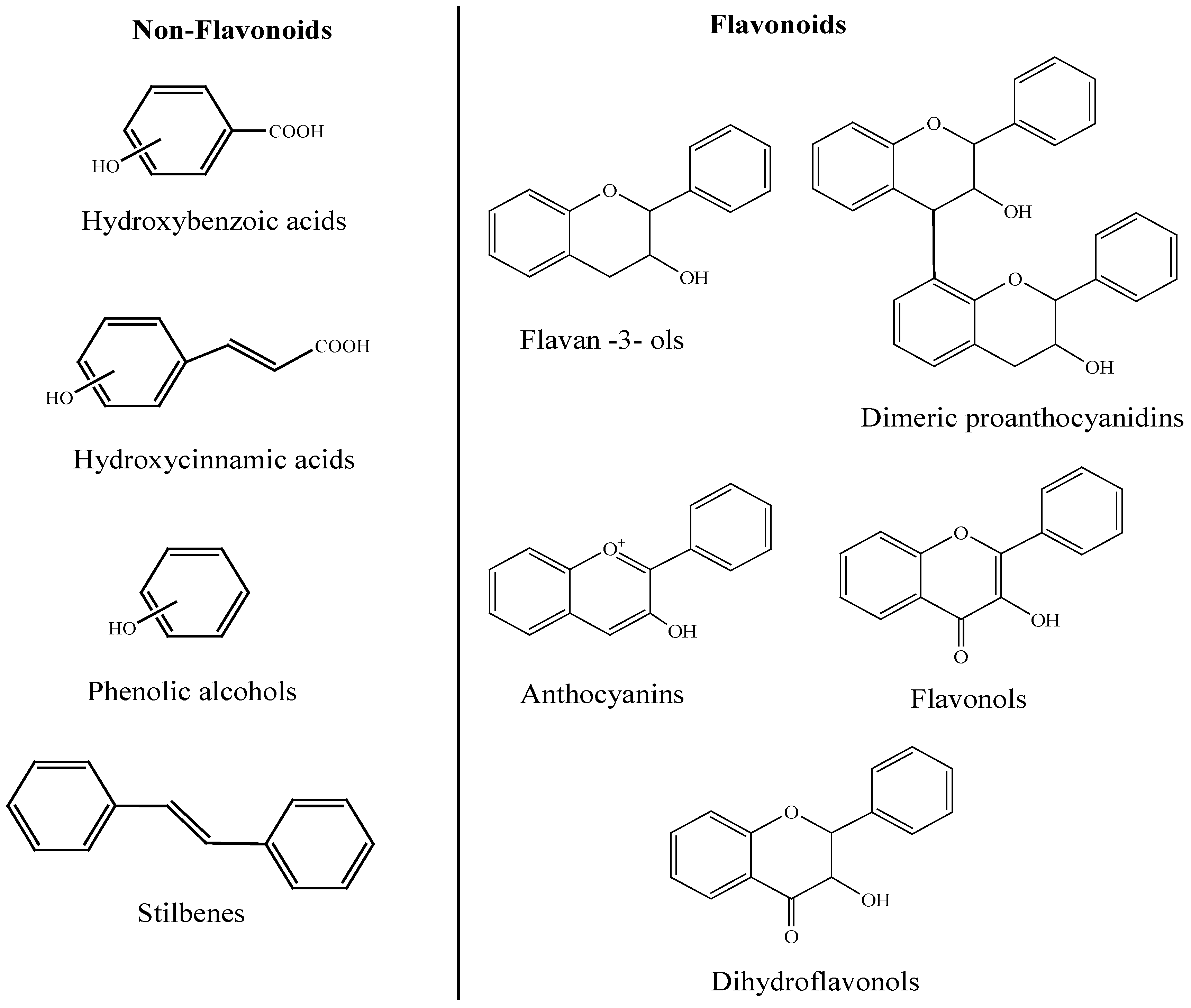

2. Phenolic Compounds in Wine

3. General Metabolism of Polyphenols in the Human Body

4. Gut Microbiota

5. Interaction between Wine Polyphenols and Gut Microbiota

5.1. Experimental Designs and Analytical Techniques

5.1.1. In Vitro Gastrointestinal Tract Simulators

5.1.2. Analytical Approaches to the Analysis of Phenolic Microbial-Derived Metabolites

5.2. Biotransformation of Wine Polyphenols by Gut Microbiota

5.3. Modulation of Gut Microbiota by Wine

| Studies Using Batch Culture Fermentation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Fecal Concentration | Phenolic Compound/Food | Dose | Time of Incubation | Microbial Technique | Growth Enhancement | Growth Inhibition | No Effect |

| [58] | 10%, w/v | (+)-Catechin | 150 mg/L, 1000 mg/L | <48 h | FISH | Lactobacillus–Enterococcus spp.; Bifidobacterium spp.; C. coccoides–E. Rectale group E. coli | C. histolyticum group | |

| [59] | 10%, w/v | Malvidin-3-O-glucoside Anthocyanidins mixture | 20 mg/L and 200 mg/L 4850 mg/L and 48,500 mg/L | <24 h | FISH | Lactobacillus–Enterococcus spp.; Bifidobacterium spp.; C. coccoides–E. rectale group | ||

| [60] | 10%, w/v | Grape seed extract fractions | 300–450 mg/L | <48 h | FISH | Lactobacillus–Enterococcus spp. | C. histolyticum group | |

| [61] | 1% w/v | Red wine extract | 600 mg/L | 48 h | FISH | C. histolyticum group | Lactobacillus–Enterococcus spp. | |

| [62] | Red wine extract | 500 mg/L | 48 h | qPCR | Lactobacillus spp.; Bifidobacterium spp.; Bacteroides spp.; Ruminococcus spp. | |||

| [63] | 20% w/v | Red wine/grape extract | 500–1000 mg/L | 72 h | HITChip | |||

| Studies Using a Gastrointestinal Simulator | ||||||||

| Reference | Simulator | Phenolic Compound/Food | Dose | Time | Microbial Technique | Population Increase | Population Decrease | No Effect |

| [64] | Twin-SHIME | Red wine-grape extract | 3 × daily dosing (1000 mg polyphenols as total daily dose) | 2 weeks | Plate count qPCR PCR-DGGE; Pyrosequencing | Klebsiella spp.; Alistipes spp.; Cloacibacillus spp.; Victivallis spp.; Akkermansia spp. | Bifidobacteria; Blautia coccoides group; Anaeroglobus spp.; Subdoligranulum spp. Bacteroides | |

| Animal Model Studies | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Simulator | Phenolic Compound/Food | Dose | Time | Microbial Technique | Population Increase | Population Decrease | No Effect | |

| [65] | Rats | Red wine polyphenols powder | 50 mg/kg | 16 weeks | Plate count | Lactobacilli; Bifidobacteria | Propionibacteria; Bacteroides; Clostridia | ||

| [66] | Broiler chicks | Grape seed extract (GSE) | 7.2 g/kg diet (GSE) (free access) | 21 days | Plate count T-RFLP | E. coli; Enterococcus spp.; Lactobacillus spp. | |||

| [67] | Pigs | Grape seed extract | 1% (free access) | 4 weeks | qPCR | Streptococcus spp.; Clostridium Cluster XIVa | Lactobacillus spp; Bifidobacterium spp. | ||

| [68] | Pigs | Grape seed extract | 1% w/w | 6 days | Ilumina MiSeq platform | Lachnospiraceae, Clostridales, Lactobacillu, Ruminococcacceae | |||

| Human Intervention Studies | |||||||||

| Reference | Volunteer Numbers | Phenolic Compound/Food | Dose | Treatment Duration | Microbial Technique | Population Increase | Population Decrease | No Effect | |

| [69] | 9 | Proantocyanidin-rich extract from grape seeds | 0.5 g/day | 6 weeks | Plate count | Bifidobacterium spp. | Enterobacteriaceae | ||

| [70] | 10 | Red wine | 272 mL/day | 20 days | qPCR | Enterococcus spp.; Prevotella spp.; Bacteroides Bifidobacterium spp.; Bacteroides uniformis Eggerthella lenta Blautia coccoides–E. rectale group | Clostridium spp.; C. histolyticum group | Actinobacteria | |

5.3.1. Studies Using Batch Culture Fermentations

5.3.2. Studies Using Human Gastrointestinal Simulators

5.3.3. Animal Model Studies

5.3.4. Human Intervention Studies

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pozo-Bayón, M.A.; Monagas, M.; Bartolome, B.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V. Wine features related to safety and consumer health: An integrated perspective. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2012, 52, 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Arranz, S.; Chiva-Blanch, G.; Valderas-Martínez, P.; Medina-Remón, A.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M.; Estruch, R. Wine, beer, alcohol and polyphenols on cardiovascular disease and cancer. Nutrients 2012, 4, 759–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berthoud, H.R.; Shin, A.C.; Zheng, H. Obesity surgery and gut-brain communication. Physiol. Behav. 2011, 105, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarner, F.; Malagelada, J.R. Gut flora in health and disease. Lancet 2003, 361, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, G.; Clifford, M.N. Colonic metabolites of berry polyphenols: The missing link to biological activity? Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 104, S48–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selma, M.V.; Espín, J.C.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A. Interaction between phenolics and gut microbiota: Role in human health. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 6485–6501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Requena, T.; Monagas, M.; Pozo-Bayón, M.A.; Martín-Alvárez, P.J.; Bartolomé, B.; del Campo, R.; Ávila, M.; Martínez-Cuesta, M.C.; Peláez, C.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V. Perspectives of the potential implications of wine polyphenols on human oral and gut microbiota. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2010, 21, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervert-Hernández, D.; Goñi, I. Dietary polyphenols and human gut microbiota: A review. Food Rev. Int. 2011, 27, 154–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuohy, K.M.; Conterno, L.; Gasperotti, M.; Viola, R. Up-regulating the human intestinal microbiome using whole plant foods, polyphenols, and/or fiber. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 8776–8782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etxebarria, U.; Fernández-Quintela, A.; Milagro, F.I.; Aguirre, L.; Martinez, J.A.; Portillo, M.P. Impact of polyphenols and polyphenol-rich dietary sources on gut microbiota composition. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 9517–9533. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Van Duynhoven, J.; Vaughan, E.E.; van Drosten, F.; Gomez-Roldan, V.; de Vos, R.; Vervoort, J.; van der Hooft, J.J.J.; Roger, L.; Draijer, R.; Jacobs, D.M. Interactions of black tea polyphenols with human gut microbiota: Implications for gut and cardiovascular health. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 1631S–1641S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardona, F.; Andrés-Lacueva, C.; Tulipani, S.; Tinahones, F.J.; Queipo-Ortuño, M.I. Benefits of polyphenols on gut microbiota and implications in human health. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2013, 24, 1415–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzounis, X.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A.; Vulevic, J.; Gibson, G.R.; Kwik-Uribe, C.; Spencer, J.P.E. Prebiotic evaluation of cocoa-derived flavanols in healthy humans by using a randomized, controlled, double-blind, crossover intervention study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urpi-Sarda, M.; Monagas, M.; Khan, N.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Sacanella, E.; Castell, M.; Permanyer, J.; Andrés-Lacueva, C. Epicatechin, procyanidins, and phenolic microbial metabolites after cocoa intake in humans and rats. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2009, 394, 1545–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Ruiz, A.; Bartolomé, B.; Martínez-Rodríguez, A.J.; Pueyo, E.; Martín-Alvárez, P.J.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V. Potential of phenolic compounds for controlling lactic acid bacteria growth in wine. Food Control. 2008, 19, 835–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertog, M.G.L.; Feskens, E.J.M.; Hollman, P.C.H.; Katan, M.B.; Kromhout, D. Dietary antioxidant flavonoids and risk of coronary heart disease: The Zutphen Elderly Study. Lancet 1993, 342, 1007–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Rio, D.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A.; Spencer, J.P.E.; Tognolini, M.; Borges, G.; Crozier, A. Dietary (poly)phenolics in human health: structures, bioavailability, and evidence of protective effects against chronic diseases. Antioxid. Redox Sign. 2013, 18, 1818–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vison, J.A.; Teufel, K.; Wu, N. Red wine, dealcoholized red wine, and especially grape juice, inhibit atherosclerosis in a harmster model. Atherosclerosis 2001, 156, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, N.; Adhami, V.M.; Mukhtar, H. Apoptosis by dietary agents for prevention and treatment of prostate cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2010, 17, R39–R52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, P.; Tedesco, I.; Russo, M.; Russo, G.L.; Venezia, A.; Cicala, C. Effects of de-alcoholated red wine and its phenolic fractions on platelet aggregation. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2001, 11, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rechner, A.R.; Kroner, C. Anthocyanins and colonic metabolites of dietary polyphenols inhibit platelet function. Thromb. Res. 2005, 116, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clifford, M.N. Diet-derived phenols in plasma and tissues and their implications for health. Planta Medica 2004, 70, 1103–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scalbert, A.; Williamson, G. Dietary intake and bioavailability of polyphenols. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 2073S–2085S. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Manach, C.; Scalbert, A.; Morand, C.; Rémésy, C.; Jiménez, L. Polyphenols: Food sources and bioavailability. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 79, 727–747. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maukonen, J.; Motto, J.; Suihko, M.L.; Saarela, M. Intra-individual diversity and similarity of salivary and faecal microbiota. J. Med. Microbiol. 2008, 57, 1560–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerritsen, J.; Smidt, H.; Rijkers, G.T.; de Vos, W.M. Intestinal microbiota in human health and disease: the impact of probiotics. Genes Nutr. 2011, 6, 209–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, W.E.; Moore, L.H. Intestinal floras of populations that have a high risk of colon cancer. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 3200–3207. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, G.R.; Roberfroid, M.B. Dietary modulation of the human colonic microbiota-Introducing the concept of prebiotics. J. Nutr. 1995, 125, 1401–1412. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guarner, F. Enteric flora in health and disease. Digestion 2006, 73, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, G.R. Dietary modulation of the human gut microflora using prebiotics. Br. J. Nutr. 1998, 80, S209–S212. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Van der Waaij, L.A.; Limburg, P.C.; Mesander, G.; van der Waaij, D. In vivo IgA coating of anaerobic bacteria in human faeces. Gut 1996, 38, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salminen, S.; Wright, A.; Morelli, L.; Marteau, P.; Brassart, D.; Vos, W.M.; Fondem, R.; Saxelin, M.; Collins, K.; Mogensen, G.; et al. Demostration of safety of probiotic—A review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1998, 44, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastall, R.A.; Gibson, G.R.; Gill, H.S.; Guarner, F.; Klaenhammer, T.R.; Pot, B.; Reid, G.; Rowland, I.R.; Sanders, M.E. Modulation of the microbial ecology of the human colon by probiotic, prebiotics and synbiotics to enhance human health: An overview of enabling science and potential applications. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2005, 52, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joly, F.; Mayeur, C.; Bruneau, A.; Noordine, M.L.; Meylheuc, T.; Langella, P.; Messing, B.; Duée, P.H.; Cherbuy, C.; Thomas, M. Drastic changes in fecal and mucosa-associated microbiota in adult patients with short bowel syndrome. Biochimie 2010, 92, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemperman, R.A.; Bolca, S.; Roger, L.C.; Vaughan, E.E. Novel approaches for analysing gut microbes and dietary polyphenols: Challeges and opportunities. Microbiology 2010, 156, 3224–3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fraher, M.H.; O’Toole, P.W.; Quigley, E.M.M. Techniques used to characterize the gut microbiota: A guide for the clinician. Nat. Rev. Gastroentero 2012, 9, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, T.C. Field guide to next-generation DNA sequencers. Mol. Ecol. Resources. 2011, 11, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boever, P.; Deplancke, B.; Verstraete, W. Fermentation by gut microbiota cultured in a simulator of the human intestinal microbial ecosystem is improved by supplementing a soygerm powder. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 2599–2606. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Molly, K.; Vande Woestyne, M.; Verstraete, W. Development of a 5 step multi-chamber reactor as a simulation of the human intestinal microbial ecosystem. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1993, 39, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-González, C.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V.; Rodríguez-Bencomo, J.J.; Cueva, C.; Martín-Álvarez, P.J.; Pozo-Bayón, M.A. Feasibility and application of liquid-liquid extraction combined with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry for the analysis of phenolic acids from grape polyphenols degraded by human faecal microbiota. Food Chem. 2012, 133, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sánchez-Patán, F.; Monagas, M.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V.; Bartolomé, B. Determination of microbial phenolic acids in human faeces by UPLC-ESI-TQ MS. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 2241–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Cañas, V.; Simó, C.; León, C.; Cifuentes, A. Advances in nutrigenomics research: Novel and future analytical approaches to invesigate the biological activity of natural compounds and food functions. J. Pharmaceut. Biomed. 2010, 51, 290–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brennan, L. Metabolomics in nutrition research: current status and perspectives. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2013, 41, 670–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llorach, R.; Garrido, I.; Monagas, M.; Urpi-Sarda, M.; Tulipani, S.; Bartolomé, B.; Andrés-Lacueva, C. Metabolomics study of human urinary metabolome modifications after intake of almond (Prunus. dulcis (Mill.) D.A. Webb) skin polyphenols. J. Proteome Res. 2010, 9, 5859–5867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monagas, M.; Urpi-Sarda, M.; Sánchez-Patán, F.; Llorach, R.; Garrido, I.; Gómez-Cordovés, C.; Andrés-Lacueva, C.; Bartolomé, B. Insights into the metabolism and microbial biotransformation of dietary flavan-3-ols and the bioactivity of their metabolites. Food Funct. 2010, 1, 233–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aura, A.M. Microbial metabolism of dietary phenolic compounds in the colon. Phytochem. Rev. 2008, 7, 407–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossen, T.; Cabrita, L.; Andersen, O.M. Colour and stability of pure anthocyanins influenced by pH including the alkaline region. Food Chem. 1998, 63, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, W.; Edwards, C.A.; Serafini, M.; Crozier, A. Bioavailability of pelargonidin-3-O-glucoside and its metabolites in humans following the ingestion of strawberries with and without cream. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGhie, T.K.; Walton, M.C. The bioavailability and absorption of anthocyanins: Towards a better understanding. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2007, 51, 702–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Ferrars, R.M.; Czank, C.; Saha, S.; Needs, P.W.; Zhang, Q.; Raheem, K.S.; Botting, N.P.; Kroon, P.A.; Kay, C.D. Methods for isolating, identifying, and quantifying anthocyanin metabolites in clinical samples. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 10052–10058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockley, C.; Teissedre, P.L.; Boban, M.; di Lorenzo, C.; Restani, P. Bioavailability of wine-derived phenolic compounds in humans: A review. Food Funct. 2012, 3, 995–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boto-Ordoñez, M.; Rothwell, J.A.; Andres-Lacueva, C.; Manach, C.; Scalbert, A.; Urpi-Sarda, M. Prediction of the wine polyphenol metabolic space: An application of the Phenol-Explorer database. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2014, 3, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Girón, A.; Queipo-Ortuno, M.I.; Boto-Ordoñez, M.; Muñoz-González, I.; Sánchez-Patán, F.; Monagas, M.; Martín-Álvarez, P.J.; Murri, M.; Tinahones, F.J.; Andres-Lacueva, C.; et al. More comparative study of microbial-derived phenolic metabolites in human feces after intake of gin, red wine, and dealcoholized red wine. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 61, 3909–3915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-González, I.; Jiménez-Girón, A.; Martín-Álvarez, P.J.; Bartolomé, B.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V. Profiling of microbial-derived phenolic metabolites in human feces after moderate red wine intake. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 9470–9479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.Q.; Meselhy, M.R.; Li, Y.; Nakamura, N.; Min, B.S.; Qin, G.W.; Hattori, M. The heterocyclic ring fission and dehydroxylation of catechins and related compounds by Eubacterium sp. strain SDG-2, a human intestinal. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2001, 49, 1640–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutschera, M.; Engst, W.; Blaut, M.; Braune, A. Isolation of catechin-converting human intestinal bacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2011, 111, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.S.; Hattori, M. Isolation and characterization of a human intestinal bacterium Eggerthella sp. CAT-1 capable of cleaving the C-Ring of (+)-catechin and (−)-epicatechin, followed by p-dehydroxylation of the B-Ring. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2012, 35, 2252–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzounis, X.; Vulevic, J.; Kuhnle, G.G.C.; George, T.; Leonczak, J.; Gibson, G.R.; Kwik-Uribe, C.; Spencer, J.P.E. Flavanol monomer-induced changes to the human faecal microflora. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 99, 782–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo, M.; Oruna-Concha, M.J.; Kolida, S.; Walton, G.E.; Kallithraka, S.; Spencer, S.P.E.; Gibson, G.R.; Pascual-Teresa, S. Metabolism of antocyanins by human gut microflora and their influence on gut bacterial growth. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 3882–3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cueva, C.; Sánchez-Patán, F.; Monagas, M.; Walton, G.E.; Gibson, G.R.; Martin-Alvarez, P.J.; Bartolome, B.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V. In vitro fermentation of grape seed flavan-3-ol fractions by human faecal microbiota: Changes in microbial groups and phenolic metabolites. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2013, 83, 729–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Patán, F.; Cueva, C.; Monagas, M.; Walton, G.E.; Gibson, G.R.; Quintanilla-Lopez, J.E.; Lebron-Aguilar, R.; Martin-Alvarez, P.J.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V.; Bartolome, B. In vitro fermentation of a red wine extract by human gut microbiota; changes in microbial groups and formation and phenolic metabolites. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 2136–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barroso, E.; Sánchez-Patán, F.; Martin-Alvarez, P.J.; Bartolome, B.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V.; Pelaez, C.; Requena, T.; van de Wiele, T.; Martinez-Cuesta, M.C. Lactobacillus plantarum IFPL935 favors the initial metabolism of red wine polyphenols when added to a colonic microbiota. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 10163–10172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, G.; Jacobs, D.M.; Peters, S.; Possemiers, S.; van Duynhoven, J.; Vaughan, E.E.; van de Wiele, T. In vitro bioconversion of polyphenols from black tea and red wine/grape juice by human intestinal microbiota displays strong interindividual variability. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 10236–10246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kemperman, R.A.; Gross, G.; Mondot, S.; Possemiers, S.; Marzorati, M.; van de Wiele, T.; Dore, J.; Vaughan, E.E. Impact of polyphenols from black tea and red wine/grape juice on a gut model microbiome. Food Res. Int. 2013, 53, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolara, P.; Luceri, C.; de Filippo, C.; Femia, A.P.; Giovannelli, L.; Caderni, G.; Cecchini, C.; Silvi, S.; Orpianesi, C.; Cresci, A. Red wine polyphenols influence carcinogenesis, intetinalmicroflora, oxidative damage and gene expression profile of colonic mucosa in F344 rats. Mutat. Res. 2005, 591, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viveros, A.; Chamorro, S.; Pizarro, M.; Arija, I.; Centeno, C.; Brenes, A. Effects of dietary polyphenols-rich grape productus on intestinal microflora and gut morphology in broiler chicks. Poultry Sci. 2011, 90, 566–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiesel, A.; Gessner, D.K.; Most, E.; Eder, K. Effects of dietary polyphenol-rich plant products from grape or hop on pro-inflammatory gene expression in the intestine, nutrient digestibility and faecal microbiota of weaned pigs. BMC Vet. Res. 2014, 10, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choy, Y.Y.; Quifer-Rada, F.; Holstege, D.M.; Frese, S.A.; Calvert, C.C.; Mills, D.A.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M.; Waterhouse, A.L. Phenolic metabolites and substantial microbiome changes in pig feces by ingesting grape seed proantocyanidins. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 2298–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamakoshi, J.; Tokutake, S.; Kikuchi, M.; Kubota, Y.; Konishi, H.; Mitsuoka, T. Effect of proantocyanidin-rich extract from grape seed on human fecal flora and fecalodor. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2001, 13, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queipo-Ortuño, M.I.; Boto-Ordoñez, M.; Murri, M.; Gómez-Zumaquero, J.M.; Clemente-Postigo, M.; Estruch, R.; Diaz, F.C.; Andres-Lacueva, C.; Tinahones, F.J. Influence of red wine polyphenols and ethanol on the gut microbiota ecology and biochemical biomarkers. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 1323–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Duynhoven, J.; Vaughan, E.E.; Jacobs, D.M.; Kemperman, R.A.; van Velzen, E.J.J.; Gross, G.; Roger, L.C.; Possemiers, S.; Smilde, A.K.; Dore, J.; et al. Metabolic fate of polyphenols in the human superorganism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 4531–4538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Velzen, E.J.J.; Wasterhuis, J.A.; van Duynhoven, J.P.M.; van Drosten, F.A.; Hoefsloot, H.C.J.; Jacobs, D.M.; Smit, S.; Draijer, R.; Kroner, C.I.; Smilde, A.K. Multilevel data analysis of a crossover designed human nutritional intervention study. J. Proteome Res. 2008, 7, 4483–4491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dueñas, M.; Cueva, C.; Muñoz-González, I.; Jiménez-Girón, A.; Sánchez-Patán, F.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V.; Bartolomé, B. Studies on Modulation of Gut Microbiota by Wine Polyphenols: From Isolated Cultures to Omic Approaches. Antioxidants 2015, 4, 1-21. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox4010001

Dueñas M, Cueva C, Muñoz-González I, Jiménez-Girón A, Sánchez-Patán F, Santos-Buelga C, Moreno-Arribas MV, Bartolomé B. Studies on Modulation of Gut Microbiota by Wine Polyphenols: From Isolated Cultures to Omic Approaches. Antioxidants. 2015; 4(1):1-21. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox4010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleDueñas, Montserrat, Carolina Cueva, Irene Muñoz-González, Ana Jiménez-Girón, Fernando Sánchez-Patán, Celestino Santos-Buelga, M. Victoria Moreno-Arribas, and Begoña Bartolomé. 2015. "Studies on Modulation of Gut Microbiota by Wine Polyphenols: From Isolated Cultures to Omic Approaches" Antioxidants 4, no. 1: 1-21. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox4010001