The Role of HIV Infection in Neurologic Injury

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Clinical Aspects and Classification of Neurological Disorders

3. Cells Involved in the Pathogenesis of HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorders

4. The role of HIV-1 in Neuronal Damage

4.1. The Direct Mechanisms

- (1)

- (2)

- (3)

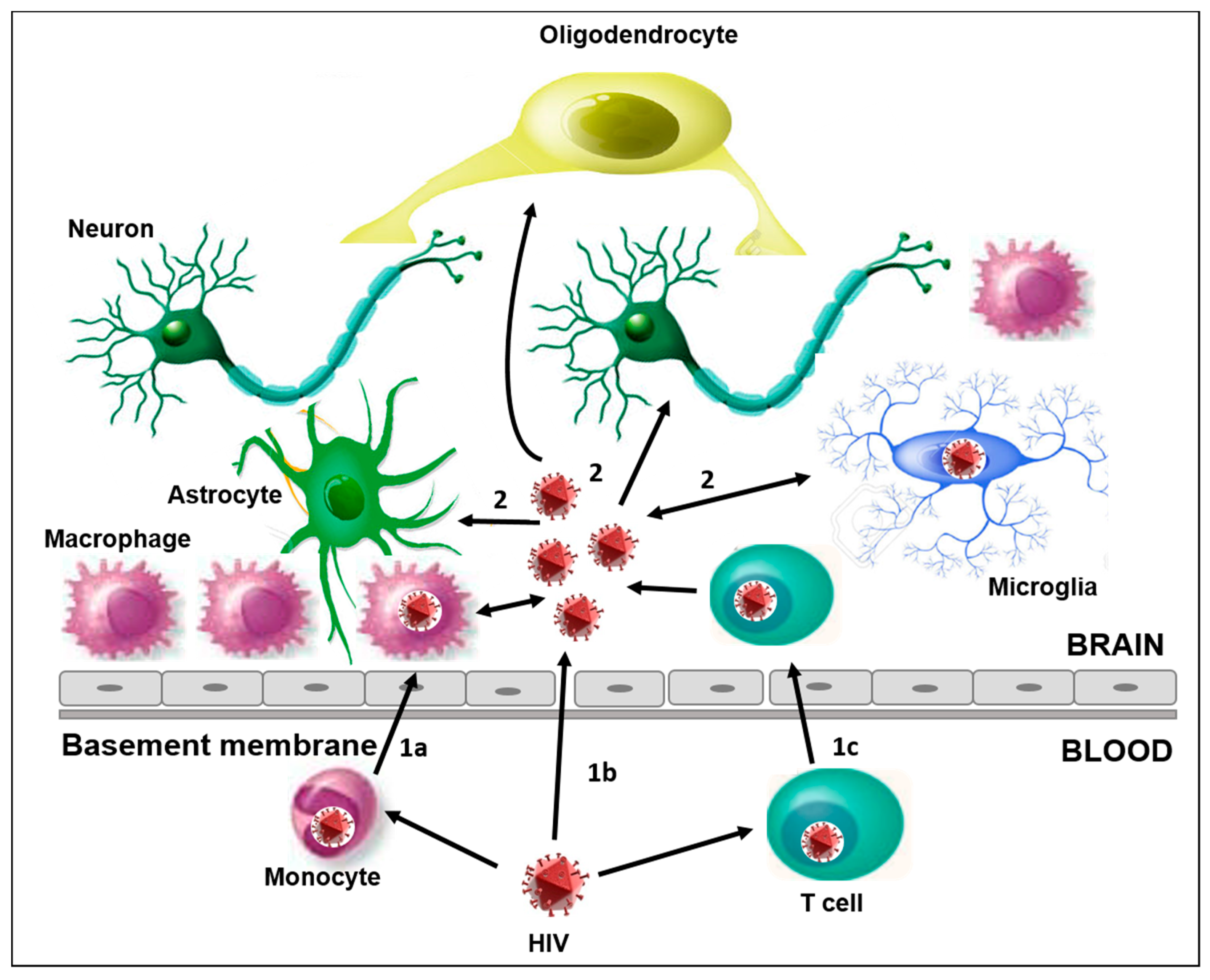

- In the “Trojan horse” hypothesis, HIV-1 infected-monocytes, leukocytes, and perivascular macrophages crossing the BBB could release viral particles able to infect resident cells like microglia, thus contributing to establishing a persistent infection. This mechanism has also been observed with other retroviruses and lentiviruses and it is probably the main mechanism for HIV penetration into the brain [43]. Several observations suggest that monocytes may be infected before leaving the bone marrow [50]. In particular, an amount of proviral DNA was found in these cells without the expression of viral proteins, thus allowing the dissemination of the HIV-1 infection [50,51]. A relevant role is played by a subset of monocytes (CD14lowCD16high) which tends to increase during HIV-1 infection [34,52,53,54,55,56]. These cells show intermediate characteristics between the monocytes and differentiated cells (macrophage and dendritic cells) [53,55]. They are more permissive to HIV replication, probably due to the lower activity of the host restriction factors than the CD14highCD16low cells [51,56], and they can more easily cross the BBB [52,53,54].

4.2. The Indirect Mechanisms

- (1)

- the infiltration of infected monocytes and lymphocytes in the CNS;

- (2)

- the release of viral and cellular factors from these infected cells;

- (3)

- the infection of resident cells by viral particles infiltrating into the CNS or released from infected cells [60].

5. The Role of HIV-1 Proteins in HAND

6. Tat

7. Gp120

8. Vpr

9. Nef

10. The Role of Co-Infections

11. Antiretroviral Therapy and HAND

12. The Compartmentalization of HIV Infection in the CNS

13. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations:

| CCL | Chemokine ligand |

| CCR3 | C-C Chemokine receptor type 3 |

| CD4 | Cluster of differentiation 4 |

| CDK | Cyclin-dependent kinase |

| Cx43 | Connexin 43 |

| CXCL | C-X-C chemokine ligand |

| CXCR4 | C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 |

| DC-SIGN | Cluster of differentiation 209 |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| GABA | γ -aminobutyric acid |

| GFAP | Glial fibrillary acid protein |

| GLUT1 | Glucose transporter 1 |

| gp120 | Glycoprotein 120 |

| GRL-04810 | nonpeptidic HIV-1 protease inhibitors |

| GRL-05010 | nonpeptidic HIV-1 protease inhibitors |

| GAC | Glutaminase C |

| HCV | Hepatitis C virus |

| HIV-1 | Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 |

| IFN-γ | Interferon γ |

| IL-1β | Interleukin 1β |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| IL-8 | Interleukin 8 |

| LC3 | Microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 |

| MAP | Microtubule associated protein |

| MAPK | Microtubule associated protein kinase |

| MCP-1 | Chemokine ligand 2 |

| MRP4 | Multidrug resistance protein 4 |

| MRP5 | Multidrug resistance protein 5 |

| MVEC | Microvascular endotelial cells |

| NEF | Negative Regulatory Factor |

| NanoART | Antiretroviral treatment nanoparticle-driven |

| NNRTI | Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors |

| PDGF | Platelet-derived growth factor |

| P-gp | P-glycoprotein |

| QUIN | Quinolinic acid |

| SYN | Synaptophysin |

| TAT | Transactivator HIV protein |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor α |

| VPR | Viral Protein R |

| β-APP | β amyloid precursor protein |

References

- Palacio, M.; Álvarez, S.; Muñoz-fernández, M.Á. HIV-1 infection and neurocognitive impairment in the current era. Rev. Med. Virol. 2012, 22, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trujillo, R.; Jaramillo-Rangel, G.; Ortega-Martinez, M.; Penalva De Oliveira, A.C.; Vidal, J.E.; Bryant, J.; Gallo, R.C. International NeuroAIDS: Prospects of HIV-1 associated neurological complications. Cell Res. 2005, 15, 962–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francisco, G.-S.; Julio, M.-G. The Neuropathogenesis of Aids. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005, 5, 69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Shapshak, P.; Kangueane, P.; Fujimura, R.K.; Commins, D.; Chiappelli, F.; Singer, E.; Levine, A.J.; Minagar, A.; Novembre, F.J.; Somboonwit, C.; et al. Editorial neuroAIDS review. AIDS 2011, 25, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhaskaran, K.; Mussini, C.; Antinori, A.; Walker, A.S.; Dorrucci, M.; Sabin, C.; Phillips, A.; Porter, K. Changes in the incidence and predictors of human immunodeficiency virus-associated dementia in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Ann. Neurol. 2008, 63, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gisslén, M.; Price, R.W.; Nilsson, S. The definition of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders: Are we overestimating the real prevalence? BMC Infect. Dis. 2011, 11, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Arminio Monforte, A.; Cinque, P.; Mocroft, A.; Goebel, F.D.; Antunes, F.; Katlama, C.; Justesen, U.S.; Vella, S.; Kirk, O.; Lundgren, J. Changing incidence of central nervous system diseases in the EuroSIDA cohort. Ann. Neurol. 2004, 55, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.-Y.; Ouyang, Y.-B.; Liu, L.-G.; Chen, D.-X. Blood-brain barrier and neuro-AIDS. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 19, 4927–4939. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rao, K.S.; Ghorpade, A.; Labhasetwar, V. Targeting anti-HIV drugs to the CNS. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2009, 6, 771–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCombe, J.A.; Vivithanaporn, P.; Gill, M.J.; Power, C. Predictors of symptomatic HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders in universal health care. HIV Med. 2013, 14, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Childs, E.A.; Lyles, R.H.; Selnes, O.A.; Chen, B.; Miller, E.N.; Cohen, B.A.; Becker, J.T.; Mellors, J.; McArthur, J. Plasma viral load and CD4 lymphocytes predict HIV-associated dementia and sensory neuropathy. Neurology 1999, 52, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, R.J.; Badiee, J.; Vaida, F.; Letendre, S.; Heaton, R.K.; Clifford, D.; Collier, A.C.; Gelman, B.; McArthur, J.; Morgello, S.; et al. CD4 nadir is a predictor of HIV neurocognitive impairment in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2011, 25, 1747–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heaton, R.K.; Clifford, D.B.; Franklin, D.R.; Woods, S.P.; Ake, C.; Vaida, F.; Ellis, R.J.; Letendre, S.L.; Marcotte, T.D.; Atkinson, J.H.; et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology 2010, 75, 2087–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, R.A.; Harezlak, J.; Schifitto, G.; Hana, G.; Clar, U.; Gongvatana, A.; Paul, R.; Taylor, M.; Thompson, P.; Alger, J.; et al. Effects of Nadir CD4 count and duration of HIV infection on brain volumes in the HAART era. J. Neurovirol. 2010, 16, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garvey, L.J.; Pavese, N.; Ramlackhansingh, A.; Thomson, E.; Allsop, J.M.; Politis, M.; Kulasegaram, R.; Main, J.; Brooks, D.J.; Taylor-Robinson, S.D.; et al. Acute HCV/HIV coinfection is associated with cognitive dysfunction and cerebral metabolite disturbance, but not increased microglial cell activation. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rempel, H.; Sun, B.; Calosing, C.; Abadjian, L.; Monto, A.; Pulliam, L. Monocyte activation in HIV/HCV coinfection correlates with cognitive impairment. PLoS ONE 2013, 2, e55776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCutchan, J.A.; Marquie-Beck, J.A.; Fitzsimons, C.A.; Letendre, S.L.; Ellis, R.J.; Heaton, R.K.; Wolfson, T.; Rosario, D.; Alexander, T.J.; Marra, C.; et al. Role of obesity, metabolic variables, and diabetes in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder. Neurology 2012, 78, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valcour, V.G.; Shiramizu, B.T.; Shikuma, C.M. HIV DNA in circulating monocytes as a mechanism to dementia and other HIV complications. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2010, 87, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spudich, S.; Gisslen, M.; Hagberg, L.; Lee, E.; Liegler, T.; Brew, B.; Fuchs, D.; Tambussi, G.; Cinque, P.; Hecht, F.M.; et al. Central nervous system immune activation characterizes primary human immunodeficiency virus 1 infection even in participants with minimal cerebrospinal fluid viral burden. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 204, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, M.A.; Castellon, S.A.; Perkins, A.C.; Ureno, O.S.; Robinet, B.; Reinhard, M.J.; Barclay, T.R.; Hinkin, C.H. Relationship between psychiatric status and frontal-subcortical systems in HIV-infected individuals. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2007, 13, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klunder, A.D.; Chiang, M.; Dutton, R.A.; Lee, S.E.; Toga, A.W.; Lopez, O.L.; Aizenstein, H.J.; Becker, J.T.; Thompson, P.M. Mapping cerebellar degeneration in HIV/AIDS. Neuroreport 2008, 19, 1655–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, R.S. Nomenclature and research case definitions for neurologic manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus-type 1 (HIV-1) infection. Neurology 1991, 41, 778–785. [Google Scholar]

- Antinori, A.; Arendt, G.; Becker, J.T.; Brew, B.J.; Byrd, D.A.; Cherner, M.; Clifford, D.B.; Cinque, P.; Epstein, L.G.; Goodkin, K.; et al. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology 2007, 69, 1789–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, K.A.; Cherry, C.L.; Bell, J.E.; McLean, C.A. Brain cell reservoirs of latent virus in presymptomatic HIV-infected individuals. Am. J. Pathol. 2011, 179, 1623–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Kim, B.O.; Gattone, V.H.; Li, J.; Nath, A.; Blum, J.; He, J.J. CD4-Independent Infection of Astrocytes by Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1: Requirement for the Human Mannose Receptor. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 4120–4133. [Google Scholar]

- Kaul, M.; Garden, G.; Lipton, S. Pathways to neuronal injury and apoptosis in HIV-associated dementia. Nature 2001, 410, 988–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coiras, M.; López-Huertas, M.R.; Pérez-Olmeda, M.; Alcamí, J. Understanding HIV-1 latency provides clues for the eradication of long-term reservoirs. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 798–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassol, E.; Alfano, M.; Biswas, P.; Poli, G. Monocyte-derived macrophages and myeloid cell lines as targets of HIV-1 replication and persistence. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2006, 80, 1018–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aquaro, S.; Bagnarelli, P.; Guenci, T.; De Luca, A.; Clementi, M.; Balestra, E.; Caliò, R.; Perno, C.F. Long-term survival and virus production in human primary macrophages infected by human immunodeficiency virus. J. Med. Virol. 2002, 68, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koppensteiner, H.; Brack-Werner, R.; Schindler, M. Macrophages and their relevance in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type I infection. Retrovirology 2012, 9, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orenstein, J.; Fox, C.; Wahl, S. Macrophages as a source of HIV during opportunistic infections. Science 1997, 276, 1857–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coiras, M. HIV-1 Latency and Eradication of Long-term Viral Reservoirs. Discov. Med. 2010, 9, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Williams, K.C.; Hickey, W.F. Central nervous system damage, monocytes and macrophages, and neurological disorders in AIDS. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2002, 25, 537–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Douce, V.; Herbein, G.; Rohr, O.; Schwartz, C. Molecular mechanisms of HIV-1 persistence in the monocyte-macrophage lineage. Retrovirology 2010, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, H.; Sun, L.; Jia, B.; Lan, X.; Zhu, B.; Wu, Y.; Zheng, J. HIV-1-infected and immune-activated macrophages induce astrocytic differentiation of human cortical neural progenitor cells via the STAT3 pathway. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aquaro, S.; Panti, S.; Caroleo, M.C.; Balestra, E.; Cenci, A.; Forbici, F.; Ippolito, G.; Mastrino, A.; Testi, R.; Mollace, V.; et al. Primary macrophages infected by human immunodeficiency virus trigger CD95-mediated apoptosis of uninfected astrocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2000, 68, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hauser, K.F.; Fitting, S.; Dever, S.M.; Podhaizer, E.M.; Knapp, P.E. Opiate drug use and the pathophysiology of neuroAIDS. Curr. HIV Res. 2012, 10, 435–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Hu, X.; Qian, L.; O’Callaghan, J.P.; Hong, J.-S. Astrogliosisi in CNS pathologies: Is there a role for Microglia? Mol. Neurobiol. 2010, 41, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farina, C.; Aloisi, F.; Meinl, E. Astrocytes are active players in cerebral innate immunity. Trends Immunol. 2007, 28, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aikaterini, A. Cellular Reservoirs of HIV-1 and their Role in Viral Persistence. Curr. HIV Res. 2008, 6, 388–400. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y.; Benveniste, E.N. Immune Function of Astrocytes. Glia 2001, 190, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narasipura, S.D.; Henderson, L.J.; Fu, S.W.; Chen, L.; Kashanchi, F.; Al-Harthi, L. Role of β-catenin and TCF/LEF family members in transcriptional activity of HIV in astrocytes. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 1911–1921. [Google Scholar]

- Albright, A.V.; Soldan, S.S.; González-Scarano, F. Pathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus-induced neurological disease. J. Neurovirol. 2003, 9, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aquaro, S.; Svicher, V.; Ronga, L.; Perno, C.F.; Pollicita, M. HIV-1-associated dementia during HAART therapy. Recent Pat. CNS Drug Discov. 2008, 3, S23–S33. [Google Scholar]

- Kohleisen, B.; Shumay, E.; Sutter, G.; Foerster, R.; Brack-Werner, R.; Nuesse, M.; Erfle, V. Stable expression of HIV-1 Nef induces changes in growth properties and activation state of human astrocytes. AIDS 1999, 13, 2331–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Henderson, L.J.; Major, E.O.; Al-Harthi, L. IFN-γ Mediates Enhancement of HIV Replication in Astrocytes by Inducing an Antagonist of the β-Catenin Pathway (DKK1) in a STAT 3-Dependent Manner. J. Immunol. 2011, 186, 6771–6778. [Google Scholar]

- Mamik, M.K.; Banerjee, S.; Walseth, T.F.; Hirte, R.; Tang, L.; Borgmann, K.; Ghorpade, A. HIV-1 and IL-1β regulate astrocytic CD38 through mitogen-activated protein kinases and nuclear factor-κB signaling mechanisms. J. Neuroinflammation 2011, 8, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhtar, M.; Harley, S.; Chen, P.; BouHamdan, M.; Patel, C.; Acheampong, E.; Pomerantz, R.J. Primary Isolated Human Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells Express Diverse HIV/SIV-Associated Chemokine Coreceptors and DC-SIGN and L-SIGN. Virology 2002, 297, 78–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hazleton, J.E.; Berman, J.W.; Eugenin, E.A. Novel mechanisms of central nervous system damage in HIV infection. HIV/AIDS 2010, 2, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bergamaschi, A.; Pancino, G. Host hindrance to HIV-1 replication in monocytes and macrophages. Retrovirology 2010, 7, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, C.M.; Wu, L. HIV interactions with monocytes and dendritic cells: Viral latency and reservoirs. Retrovirology 2009, 6, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strazza, M.; Pirrone, V.; Wigdahl, B.; Nonnemacher, M.R. Breaking down the Barrier: The effects of HIV-1 on the Blood-Brain Barrier. Brain Res. 2011, 1399, 96–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavegnano, C.; Schinazi, R.F. Antiretroviral therapy in macrophages: Implication for HIV eradication. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 2010, 20, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meléndez, L.M.; Colon, K.; Rivera, L.; Rodriguez-Franco, E.; Toro-Nieves, D. Proteomic analysis of HIV-infected macrophages. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2011, 6, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowe, S.; Zhu, T.; Muller, W.A. The contribution of monocyte infection and trafficking to viral persistence, and maintenance of the viral reservoir in HIV infection. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2003, 74, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellery, P.J.; Tippett, E.; Chiu, Y.; Paukovics, G.; Cameron, P.U.; Solomon, A.; Lewis, R.S.; Gorry, P.R.; Jawarowski, A.; Greene, W.C.; et al. The CD16+ Monocyte Subset Is More Harbors HIV-1 In Vivo. J. Immunol. 2007, 178, 6581–6589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, N.A.; Di Cello, F.; Stins, M.; Kim, K.S. Gp120-mediated cytotoxicity of human brain microvascular endothelial cells is dependent on p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation. J. Neurovirol. 2007, 13, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acheampong, E.; Parveen, Z.; Muthoga, L.W.; Kalayeh, M.; Mukhatar, M.; Pomerantz, R.J. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Nef Potently Induces Apoptosis in Primary Human Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells via the Activation of Caspases. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 4257–4269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, A.Y.; Chung, R.T. Coinfection with HIV-1 and HCV-a one-two punch. Gastroenterology 2009, 137, 795–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guha, D.; Nagilla, P.; Redinger, C.; Srinivasan, A.; Schatten, G.P.; Ayyavoo, V. Neuronal apoptosis by HIV-1 Vpr: Contribution of proinflammatory molecular networks from infected target cells. J. Neuroinflammation 2012, 9, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.; Banks, W.A. Role of the Immune System in HIV-associated Neuroinflammation and Neurocognitive Implications. Brain Behav. Immun. 2015, 45, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vera, J.H.; Guo, Q.; Rabiner, I.; Matthews, P.; Gunn, R.; Winston, A. Neuroinflammation in Asymptomatic HIV-Infected Subjects On Effective cART. In Proceedings of the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) 2014, Boston, MA, USA, 3–6 March 2014. Abstract 486LB. [Google Scholar]

- Vera, J.H.; Guo, Q.; Cole, J.; Boasso, A.; Greathead, L.; Kelleher, P.; Rabiner, I.; Bishop, C.; Matthews, P.; Gunn, R.; et al. Microbial Translocation is associated with Neuroinflammation in HIV-infected subjects on ART. In Proceedings of the 22nd Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Seattle, WA, USA, 23–26 February 2015. Abstract 477. [Google Scholar]

- Kovalevich, J. Neuronal toxicity in HIV CNS disease. Future Virol. 2012, 7, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gendelman, H.E.; Lipton, S.A.; Tardieu, M.; Bukrinsky, M.I.; Nottet, H.S. The neuropathogenesis of HIV-1 infection. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1994, 56, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Franco, E.J.; Cantres-Rosario, Y.M.; Plaud-Valentin, M.; Romeu, R.; Rodríguez, Y.; Skolasky, R.; Meléndez, V.; Cadilla, C.L.; Melendez, L.M. Dysregulation of macrophage-secreted cathepsin B contributes to HIV-1-linked neuronal apoptosis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e36571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscoli, C.; Salvemini, D.; Paolino, D.; Iannone, M.; Palma, E.; Cufari, A.; Rotiroti, D.; Perno, C.F.; Aquaro, S.; Mollace, V. Peroxynitrite decomposition catalyst prevents apoptotic cell death in a human astrocytoma cell line incubated with supernatants of HIV-infected macrophages. BMC Neurosci. 2002, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollicita, M.; Muscoli, C.; Sgura, A.; Biasin, A.; Granato, T.; Masuelli, L.; Mollace, V.; Tanzarella, C.; Del Duca, C.; Rodinò, P.; et al. Apoptosis and telomeres shortening related to HIV-1 induced oxidative stress in an astrocytoma cell line. BMC Neurosci. 2009, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Zhu, X.; Ma, T.; Wang, J.; Wang, F.; Zhang, S. The p38 MAPK NF-κB pathway, not the ERK pathway, is involved in exogenous HIV-1 Tat-induced apoptotic cell death in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2013, 31, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debaisieux, S.; Rayne, F.; Yezid, H.; Beaumelle, B. The ins and outs of HIV-1 Tat. Traffic 2012, 13, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wayman, W.N.; Dodiya, H.B.; Person, A.L.; Kashanchi, F.; Kordower, J.H.; Hu, X.T.; Napier, C. Enduring cortical alterations after a single in vivo treatment of HIV-1 Tat. Neuroreport 2012, 23, 825–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutile-McMenemy, N.; Elfenbein, A.; Deleo, J.A. Minocycline decreases in vitro microglial motility, beta1-integrin, and Kv1.3 channel expression. J. Neurochem. 2007, 103, 2035–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.-M.; Tremblay, M.-È.; King, I.L.; Qi, J.; Reynolds, H.M.; Marker, D.F.; Varrone, J.J.P.; Majewska, A.K.; Dewhurst, S.; Gelbard, H.A. HIV-1 Tat-induced microgliosis and synaptic damage via interactions between peripheral and central myeloid cells. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nath, A.; Conant, K.; Chen, P.; Scott, C.; Major, E.O. Transient Exposure to HIV-1 Tat Protein Results in Cytokine Production in Macrophages and Astrocytes. A Hit and Run Phenomenon. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 17098–17102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; He, J.J. HIV-1 Tat induces unfolded protein response and endoplasmic reticulum stress in astrocytes and causes neurotoxicity through GFAP activation and aggregation. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 22819–22829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, J.; Carvallo, L.; Buckner, C.M.; Luers, A.; Prevedel, L.; Bennett, M.V.; Eugenin, E.A. HIV-tat alters Connexin43 expression and trafficking in human astrocytes: Role in NeuroAIDS. J. Neuroinflammation 2016, 13, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zucchini, S.; Pittaluga, A.; Brocca-Cofano, E.; Summa, M.; Fabris, M.; De Michele, R.; Bonaccorsi, A.; Busatto, G.; Barbanti Brodano, G.; Altavilla, G.; et al. Increased excitability in tat-transgenic mice: Role of tat in HIV-related neurological disorders. Neurobiol. Dis. 2013, 55, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, A.H.; Thayer, S.A. Human immunodeficiency virus-1 protein Tat induces excitotoxic loss of presynaptic terminals in hippocampal cultures. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2013, 54, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Midde, N.; Gomez, A.; Zhu, J. HIV-1 Tat decreases dopamine Transporter cell surface expression and vescicular monoamine transporter-2 function in Rat striatal synaptosomes. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2012, 7, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Martemyanov, K.A.; Thayer, S.A. Human immunodeficiency virus protein Tat induces synapse loss via a reversible process that is distinct from cell death. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 12604–12613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theodore, S.; Cass, W.; Dwoskin, L.; Maragos, W. HIV-1 protein Tat inhibits vesicular monoamine transporter-2 activity in rat striatum. Synapse 2012, 66, 755–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Hage, N.; Podhaizer, E.M.; Sturgill, J.; Hauser, K.F. Toll-like receptor expression and activation in astroglia: Differential regulation by HIV-1 Tat, gp120, and morphine. Immunol. Investig. 2011, 40, 498–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fields, J.; Dumaop, W.; Rockenstein, E.; Mante, M.; Spencer, B.; Grant, I.; Ellis, R.; Letendre, S.; Patrick, C.; Adame, A.; et al. Age-dependent molecular alterations in the autophagy pathway in HIVE patients and in a gp120 tg mouse model: Reversal with beclin-1 gene transfer. J. Neurovirol. 2013, 19, 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Liu, J.; Xu, C.; Keblesh, J.; Zang, W.; Xiong, H. HIV-1gp120 induces neuronal apoptosis through enhancement of 4-aminopyridine-senstive outward K+ currents. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e25994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Katafiasz, B.; Fox, H.; Xiong, H. HIV-1 gp120-Induced Axonal Injury Detected by Accumulation of β-Amyloid Precursor Protein in Adult Rat Corpus Callosum. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2012, 6, 650–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kogan, M.; Deshmane, S.; Sawaya, B.; Gracely, J.; Khalili, K.; Rappaport, J. Inhibition of NF-kB activity by HIV-1 Vpr is dependent on Vpr binding protein. J. Cell. Physiol. 2013, 228, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamers, S.; Fogel, G.; Singer, E.J.; Salemi, M.; Nolan, D.J.; Huysentruyt, L.C.; McGrath, M.S. HIV-1 Nef in Macrophage-Mediated Disease Pathogenesis. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2012, 31, 432–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masanetz, S.; Lehmann, M.H. HIV-1 Nef increases astrocyte sensitivity towards exogenous hydrogen peroxide. Virol. J. 2011, 8, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laforge, M.; Petit, F.; Estaquier, J.; Senik, A. Commitment to apoptosis in CD4(+) T lymphocytes productively infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is initiated by lysosomal membrane permeabilization, itself induced by the isolated expression of the viral protein Nef. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 11426–11440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, R.; Dunning, J.; Nelson, M. HIV and hepatitis C co-infection. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2005, 59, 1082–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clifford, D.B.; Yang, Y.; Evans, S. Neurologic consequences of hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency virus coinfection. J. Neurovirol. 2005, 11 (Suppl. S3), 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilsabeck, R.C.; Castellon, S.A.; Hinkin, C.H. Neuropsychological aspects of coinfection with HIV and hepatitis C virus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 41 (Suppl. S1), S38–S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, E.L.; Morgello, S.; Isaacs, K.; Naseer, M.; Gerits, P. Neuropsychiatric impact of hepatitis C on advanced HIV. Neurology 2004, 62, 957–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spudich, S.; González-Scarano, F. HIV-1-related central nervous system disease: Current issues in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a007120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivithanaporn, P.; Maingat, F.; Lin, L.Z.; Na, H.; Richardson, D.C.; Agrawa, B.; Cohen, E.A.; Jhamandas, J.H.; Power, C. Hepatitis C Virus Core Protein Induces Neuroimmune Activation and Potentiates Human Immunodeficiency Virus-1 Neurotoxicity. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e12856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antinori, A.; Fedele, V.; Pinnetti, C.; Lorenzini, P.; Carta, S.; Bordoni, V.; Martini, F.; Ceccherini-Silberstein, F.; Ammassari, A.; Perno, C.F. Role of HCV co-infection on CSF biomarkers in HIV patients. In Proceedings of the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) 2016, Boston, MA, USA, 22–25 February 2016. Abstract 413. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, Y.; Sharer, L.R.; Dewhurst, S.; Blumberg, B.M.; Hall, C.B.; Epstein, L.G. Cellular localization of human herpesvirus-6 in the brains of children with AIDS encephalopathy. J. Neurovirol. 1995, 1, 30–39. [Google Scholar]

- Barigou, M.; Garnier, C.; Debard, A.; Mengelle, C.; Dumas, H.; Porte, L.; Delobel, P.; Bonneville, F.; Marchou, B.; Martin-Blondel, G. Favorable outcome of severe human herpes virus-6 encephalitis in an HIV-infected patient. AIDS 2016, 30, 532–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escobar-Villalba, A.; Sainz de la Maza, S.; Pérez Torre, P.; Galán, J.C.; Rodríguez-Domínguez, M.; Monreal Laguillo, E.; Martínez Ulloa, P.L.; Buisán Catevilla, J.; Corral, I. Acute myelitis by human herpes virus 7 in an HIV-infected patient. J. Clin. Virol. 2016, 77, 63–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, C.S.; Koralnik, I.J. Beyond progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: Expanded pathogenesis of JC virus infection in the central nervous system. Lancet Neurol. 2010, 9, 425–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbue, S.; Elia, F.; Signorini, L.; Bella, R.; Villani, S.; Marchioni, E.; Ferrante, P.; Phan, T.G.; Delwart, E. Human polyomavirus 6 DNA in the cerebrospinal fluid of an HIV-positive patient with leukoencephalopathy. J. Clin. Virol. 2015, 68, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Santiago, J.; Gianella, S.; Bharti, A.; Cooksonv, D.; Heaton, R.K.; Grant, I.; Letendre, S.; Peterson, S.N. The human gut microbiome and hiv-associated neurocognitive disorders. In Proceedings of the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–16 February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents Last updated July 14, 2016. Availabel online: https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/adultandadolescentgl.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2016).

- Nowacek, A.; Gendelman, H. NanoART, neuroAIDS and CNS drug delivery. Nanomedicine 2009, 4, 557–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleasby, K.; Castle, J.C.; Roberts, C.J.; Cheng, C.; Bailey, W.J.; Sina, J.F.; Kulkarni, A.V.; Hafey, M.J.; Evers, R.; Johnson, J.M.; et al. Expression profiles of 50 xenobiotic transporter genes in humans and pre-clinical species: A resource for investigations into drug disposition. Xenobiotica 2006, 36, 963–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ene, L.; Duiculescu, D.; Ruta, S.M. How much do antiretroviral drugs penetrate into the central nervous system? J. Med. Life 2011, 4, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Varatharajan, L.; Thomas, S.A. The transport of anti-HIV drugs across blood-CNS interfaces: Summary of current knowledge and recommendations for further research. Antivir. Res. 2009, 82, A99–A109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strazielle, N.; Ghersi-Egea, J.-F. Factors affecting delivery of antiviral drugs to the brain. Rev. Med. Virol. 2005, 15, 105–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letendre, S.L.; Ellis, R.J.; Ances, B.M.; McCutchan, J.A. Neurologic complications of HIV disease and their treatment. Top HIV Med. 2010, 18, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Letendre, S.; Marquie-Beck, J. Validation of the CNS Penetration-Effectiveness rank for quantifying antiretroviral penetration into the central nervous system. Arch. Neurol. 2008, 65, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiandra, L.; Capetti, A.; Sorrentino, L.; Corsi, F. Nanoformulated Antiretrovirals for Penetration of the Central Nervous System: State of the Art. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2017, 12, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, B.M.; Letendre, S.L.; Brigid, E.; Clifford, D.B.; Collier, A.C.; Gelman, B.B.; Mcarthur, J.C.; Mccutchan, J.A.; Simpson, D.M.; Ellis, R.; et al. Low Atazanavir Concentrations In Cerebrospinal Fluid. AIDS 2009, 23, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira, F.T.M.; do Olival, G.S.; de Oliveira, A.C.P. Central Nervous System Antiretroviral High Penetration Therapy. J. AIDS Clin. Res. 2015, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saksena, N.K.; Wang, B.; Zhou, L.; Soedjono, M.; Ho, Y.S.; Conceicao, V. HIV reservoirs in vivo and new strategies for possible eradication of HIV from the reservoir sites. HIV/AIDS 2010, 2, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aquaro, S.; Perno, C.F.; Balestra, E.; Balzarini, J.; Cenci, A.; Francesconi, M.; Panti, S.; Serra, F.; Villani, N.; Caliò, R. Inhibition of replication of HIV in primary monocyte/macrophages by different antiviral drugs and comparative efficacy in lymphocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1997, 62, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kaur, I.P.; Bhandari, R.; Bhandari, S.; Kakkar, V. Potential of solid lipid nanoparticles in brain targeting. J. Control. Release 2008, 127, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, F.; Fadda, A.M.; Sinico, C. Liposomes for brain delivery. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2013, 10, 1003–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saiyed, Z.M.; Gandhi, N.H.; Nair, M.P.N. Magnetic nanoformulation of azidothymidine 5′-triphosphate for targeted delivery across the blood-brain barrier. Int. J. Nanomed. 2010, 5, 157–166. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Lin, B.; Shao, W.; Zhu, Z.; Ji, T.; Yang, C. In vitro and in vivo studies on the transport of PEGylated silica nanoparticles across the blood–brain barrier. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 2131–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Dai, Q.; Morshed, R.A.; Fan, X.; Wegscheid, M.L.; Wainwright, D.A.; Han, Y.; Zhang, L.; Auffinger, B.; Tobias, A.L.; et al. Blood–brain barrier permeable gold nanoparticles: An efficient delivery platform for enhanced malignant glioma therapy and imaging. Small 2014, 29, 5137–5150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgmann, K.; Rao, K.; Labhasetwar, V.; Ghorpade, A. Efficacy of Tat-conjugated ritonavir-loaded nanoparticles in reducing HIV-1 replication in monocyte-derived macrophages and cytocompatibility with macrophages and human neurons. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 2011, 27, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marra, C.M.; Zhao, Y.; Clifford, D.B.; Letendre, S.; Evans, S.; Henry, K.; Ellis, R.J.; Rodriguez, B.; Coombs, R.W.; Schifitto, G.; et al. Impact of combination antiretroviral therapy on cerebrospinal fluid HIV RNA and neurocognitive performance. AIDS 2009, 23, 1359–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caniglia, E.C.; Cain, L.E.; Justice, A.; Tate, J.; Logan, R.; Sabin, C.; Winston, A.; van Sighem, A.; Miro, J.M.; Podzamczer, D.; et al. Antiretroviral penetration into the CNS and incidence of AIDS-defining neurologic conditions. Neurology 2014, 83, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, K.R.; Su, Z.; Margolis, D.M.; Krambrink, A.; Havlir, D.V.; Evans, S.; Skiest, D.J. Neurocognitive effects of treatment interruption in stable HIV-positive patients in an observational cohort. Neurology 2010, 74, 1260–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akay, C.; Cooper, M.; Odeleye, A.; Jensen, B.K.; White, M.G.; Vassoler, F.; Gannon, P.J.; Mankowski, J.; Dorsey, J.L.; Buch, A.M.; et al. Antiretroviral drugs induce oxidative stress and neuronal damage in the central nervous system. J. Neurovirol. 2014, 20, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akay-Espinoza, C.; Stern, A.L.; Nara, R.L.; Panvelker, N.; Li, J.; Jordan-Sciutto, K.-L. Differential in vitro neurotoxicity of antiretroviral drugs. In Proceedings of the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–16 February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, K.; Liner, J.; Meeker, R.B. Antiretroviral neurotoxicity. J. Neurovirol. 2012, 18, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strain, M.C.; Letendre, S.; Pillai, S.K.; Russell, T.; Ignacio, C.C.; Günthard, H.F.; Good, B.; Smith, D.M.; Wolincky, S.M.; Furtado, M.; et al. Genetic composition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in cerebrospinal fluid and blood without treatment and during failing antiretroviral therapy. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 1772–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrington, P.R.; Schnell, G.; Letendre, S.L.; Ritola, K.; Robertson, K.; Hall, C.; Burch, C.L.; Jabarac, C.B.; Moore, D.T.; Ellis, R.J.; et al. Cross-sectional characterization of HIV-1 env compartmentalization in cerebrospinal fluid over the full disease course. AIDS 2009, 23, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnell, G.; Spudich, S.; Harrington, P.; Price, R.W.; Swanstrom, R. Compartmentalized human immunodeficiency virus type 1 originates from long-lived cells in some subjects with HIV-1-associated dementia. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulie, C.; Fourati, S.; Lambert-Niclot, S.; Tubiana, R.; Canetri, A.; Girard, P.M.; Katlama, C.; Morand-Joubert, L.; Calvez, V.; Merceli, A.G. HIV genetic distance between plasma and CSF in patients with neurological disorders. In Proceedings of the International HIV and Hepatitis Drug Resistance Workshop, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 8–12 June 2010. Abstract 127. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, M.F.; Chaillon, A.; Nakazawa, N.; Vargas, M.; Letendre, S.L.; Strain, M.C.; Ellis, R.J.; Morris, S.; Little, S.J.; Smith, D.M.; et al. Early Antiretroviral Therapy is Associated with Lower HIV DNA Molecular Diversity and Lower Inflammation in Cerebrospinal Fluid but Does Not Prevent the Establishment of Compartmentalized HIV DNA Populations. PLOS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nightingale, S.; Geretti, A.M.; Beloukas, A.; Fisher, M.; Winston, A.; Else, L.; Nelson, M.; Taylor, S.; Ustianowski, A.; Ainsworth, J.; et al. Discordant CSF/plasma HIV-1 RNA in patients with unexplained low-level viraemia. J. Neurovirol. 2016, 22, 852–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cell Type | Infection Type | Effects in the Brain a |

|---|---|---|

| Astrocyte | Restricted | Increases BBB permeability; Promotes the migration of monocytes into the brain; Increases the release of intracellular Ca2+ and glutamate; Decreases the glutamate uptake; Increases neurotoxins production |

| Microglia | Productive | Induces the release of viral proteins (gp120, Tat, Vpr); Induces neurotoxins production (inflammatory mediators, PDGF, QUIN); Actives viral replication |

| Neuron | Restricted | Increases the release of intracellular Ca2+; Increases caspase activation; Increases p53 expression |

| Oligodendrocyte | Restricted | Reduces myelin synthesis; Increases intracellular Ca2+ levels; Increases cellular apoptosis |

| Perivascular Macrophage | Productive | Induces the release of viral proteins (gp120, Tat, Vpr); Induces the neurotoxins production (inflammatory mediators, PDGF, QUIN); Actives viral replication |

| Regulatory Protein | Effects on Hand |

|---|---|

| Tat |

|

| Gp120 |

|

| Vpr |

|

| Nef |

|

| Drug Class | Drug a | CNS Penetration b |

|---|---|---|

| Entry/Fusion inhibitors | ENF | Low |

| MVC | High | |

| Integrase strand Transfer inhibitor | RAL | Medium |

| EVG | Medium | |

| Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase inhibitor | ZDV | High |

| 3TC | Medium | |

| D4T | Medium | |

| DDI | Medium | |

| ABC | Medium | |

| TDF | Low | |

| FTC | medium | |

| Non-nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase inhibitor | EFV | medium |

| NVP | High | |

| DLV | High | |

| ETR | Low | |

| Protease inhibitor | APV | medium |

| IDV | medium | |

| DRV | medium | |

| RTV | Low | |

| LPV | Medium | |

| NFV | Low | |

| SQV | Low | |

| ATV | Medium | |

| FPV | Medium | |

| TPV | Low |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Scutari, R.; Alteri, C.; Perno, C.F.; Svicher, V.; Aquaro, S. The Role of HIV Infection in Neurologic Injury. Brain Sci. 2017, 7, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci7040038

Scutari R, Alteri C, Perno CF, Svicher V, Aquaro S. The Role of HIV Infection in Neurologic Injury. Brain Sciences. 2017; 7(4):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci7040038

Chicago/Turabian StyleScutari, Rossana, Claudia Alteri, Carlo Federico Perno, Valentina Svicher, and Stefano Aquaro. 2017. "The Role of HIV Infection in Neurologic Injury" Brain Sciences 7, no. 4: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci7040038