1. Spatial Concept

‘Space of Refuge’ is a spatial concept and intervention that emanated from extensive fieldwork inside Palestinian refugee camps, namely Baqa’a camp in Jordan and Burj el-Barajneh camp in Lebanon. This was part of my Ph.D research at the Bartlett School of Architecture, which directly addresses issues of inhabitation within Palestinian refugee camps in different host countries. It investigates modes of spatial practice and production by both the refugees inhabiting the camp and the host governments hosting the camps—from the onset of creating these spaces, while situating the term

spatial here within the historical narrative of the Palestinian camp as a concept of space (refugee camp); and actual materiality of space (tent to concrete); and the resulting established camp-assemblage emanating from a culture of making space inside a regulated and protracted space of refuge. What emerged was a clear demonstration of the impact of a protraction of refuge over space, whereby refugees reappropriated the architectural physicality of the camp over the span of 70 years through producing space that challenged the United Nations’ imposed parameters and standards.

1 These standards formed a rigid, grid-like layout of allocated refugee-family plots, beyond which one is not allowed to build space. In addition, the refugees had to adhere to host government policies and restrictions on building materials and heights.

2The Palestinian refugees realized their inevitable protraction early on, and thus opted to build up their spaces by transgressing the aforementioned delineated lines, employing what I call acts of

spatial violation. These acts, considered an official violation inside the camp by the UN and the host government (

Sanyal 2014), are nonetheless tolerated, and have enabled the refugees to construct a

Palestinian Scale, in physical, architectural terms, which proved to be detrimental as it reached a spatial threshold over a protracted refuge, deemed threatening by the host governments. This new scale, beyond UN and host country parameters

3, provided a camp tissue unequivocal to the refugee, yet inaccessible to the host government security apparatuses. This new spatial condition prompted these host governments to adopt modes of spatial intervention meant to fragment and resize the camp’s scale, through opening new wide streets that divide the camp into smaller accessible areas (

Achilli 2015, p. 271), or, in some more violent cases, through the complete destruction of the camp, of which Nahr al-Bared camp in Lebanon was the most recent case in 2007 (

Hassan and Hanafi 2010).

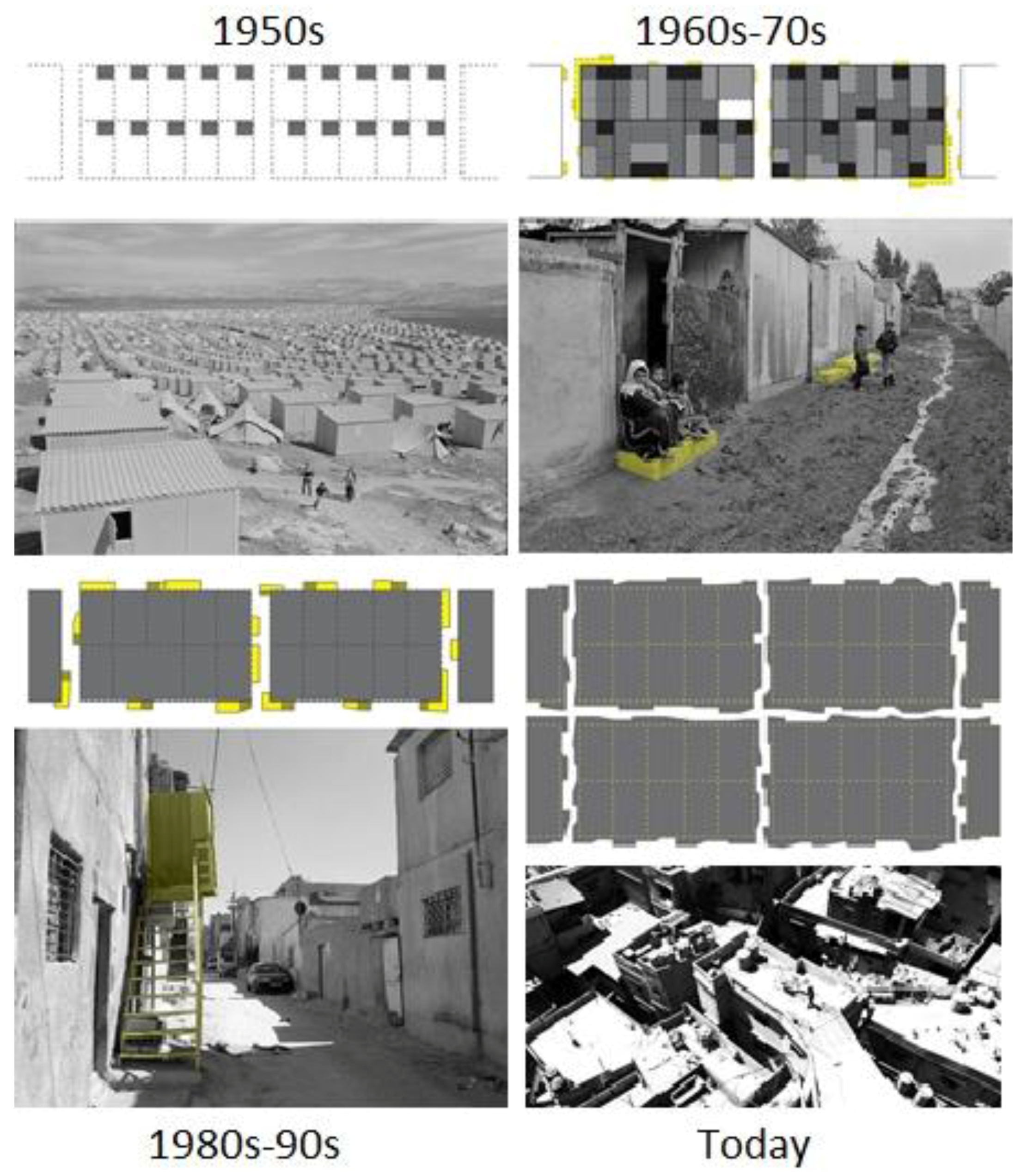

The diagram below showcases, through mapping, the evolution of the Palestinian camp’s architecture, demonstrated through the progression of acts of spatial violation inside the camp.

Building the Palestinian Scale

The first attempt to regulate the scale of the Palestinian camp was the UN’s camp layout of a grid system in the 1950s consisting of demarcated refugee plots (100 m2) entitled as “right-of-use” for each refugee family, and housing within it a three-by-four-meter asbestos room (in solid grey, top-left). Anything built beyond the demarcated 100m2 plot would be considered a spatial violation. Amenities were provided as public nodes throughout the camp, which prompted the refugee families to immediately construct their own private amenities inside the plot, rapidly saturating the horizontal plane in the 1960s–70s, and initiating horizontal encroachments beyond the plot in the form of Attabat (outdoor thresholds, top-right). As horizontal encroachments became difficult, refugees devised another “architectural element” in the 1980s–90s in the form of makeshift external stairs to facilitate vertical expansions (bottom-left), often considered a spatial violation due to the host government’s height restrictions. Today, the camp—enabled by acts of spatial violation—has reached a scale transgressing humanitarian regulations, and creating spatial economies (for example renting and selling space) which contests humanitarian and host country policies, while at the same time attesting to their containment and control.

2. ‘Space of Refuge’—A Spatial Installation inside the Palestinian Camp

After spending four years conducting fieldwork inside the camps between 2014–2017, and confronted with the reality of camp-spaces being physically altered by host governments to hinder their potential collective agency, it was clear that the urgent need inside the camp was not its architecture, but precisely the operation of it—socially, economically, and most importantly politically. In more specific terms, considering the sociopolitical barriers and the prohibition of discussing conflict overtly inside the Palestinian camp, the need that emerged from the field studies was not that of building actual space, but of discussing space and its sociopolitical determinations on the camp and the refugees. To be able to formulate this inside the Palestinian camp, the interventions needed to be designed utilizing spatial means with the aim of transferring this spatial knowledge to other camps in different host countries, and to global cities (of which London was the first) to augment this critical discussion about space and refuge, and in turn create a spatial network constructed from sharing spatial knowledge. Every time the installation travels to a different space, it opens up yet another hybrid, third space where questions of socio-spatial challenges are addressed.

To ensure a genuine and constructive new space for dialogue inside the camp, the intervention needed to plug into the existing spatiality of the camp, and act as a new, yet harmonious element within the larger existing camp apparatus.

4 Through recreating methods and materiality of construction developed and used inside the camp, ‘Space of Refuge’ emerged as a installation concerned with negotiating space through space-making by constructing a spatial installation which directly addressed “scale” and “production of space”. Inside a rich, complex, and unstable space, such as the Palestinian camp, the interventions were imagined as devices that can cause a disruption to the existing understanding of space and a platform to discuss it. In addition, these interventions would serve as devices to re-map academic and theoretical understanding of spaces of refuge through challenging existing notions and definitions of said spaces.

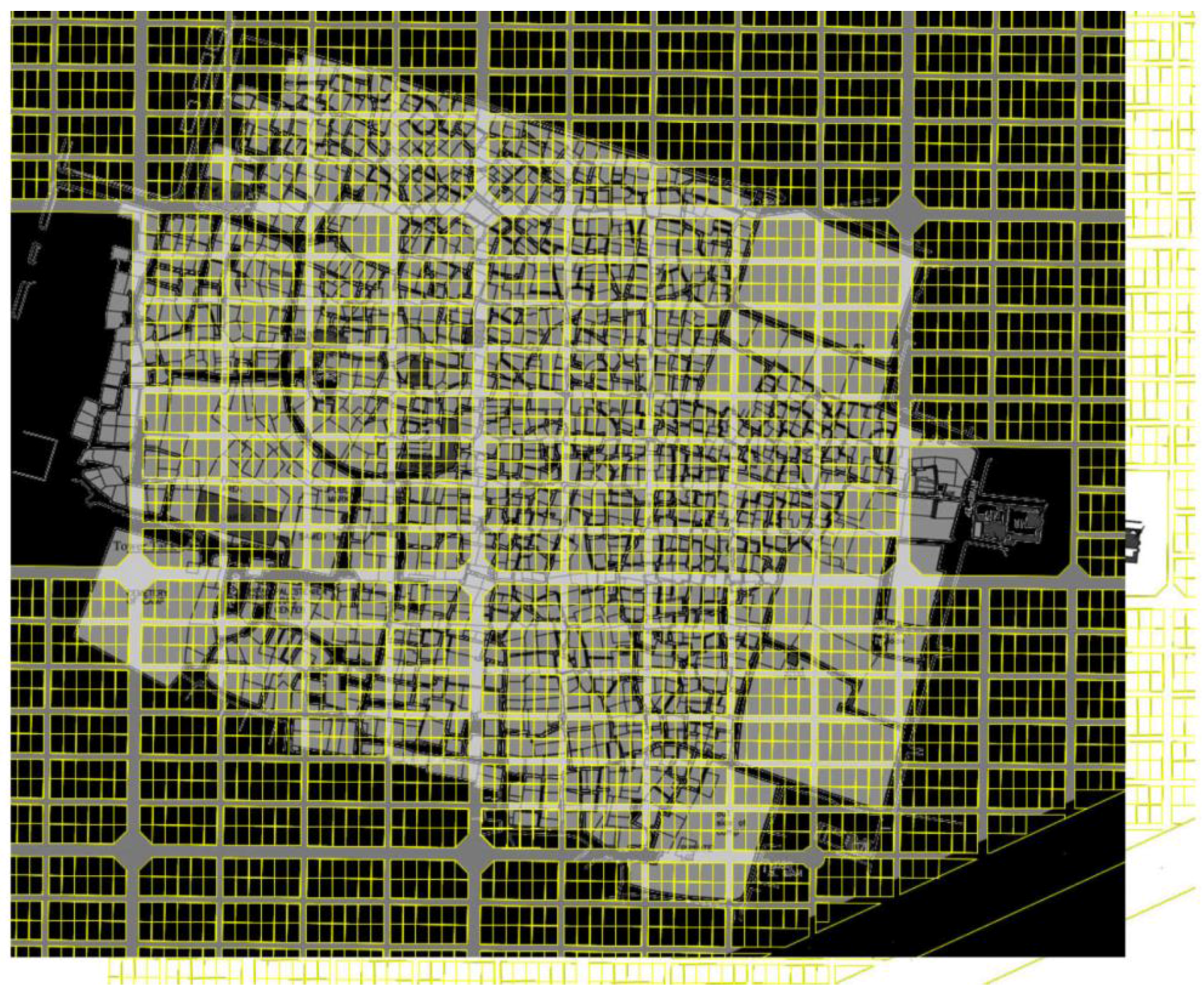

The ‘Space of Refuge’ installation superimposes two Palestinian camp-scales in two different host countries: Baqa’a camp in Jordan and Burj el-Barajneh camp in Lebanon (refer to Diagram below). In doing so, the installation reveals how each group of refugees in both countries has come to adopt a very different method of spatial production and to engage in very different forms of spatial violation. The installation incorporates multimedia formats, including film, sound pieces, and photography, always with the aim to create a more democratic form of dialogue.

Diagram showing the superimposition of two camp scales, Baqa’a camp in yellow and Burj el-Barajneh camp in grey.

2.1. ‘Space of Refuge’ in Baqa’a Camp, Jordan, 2015

(L) An image of Burj el-Barajneh camp in 2014, Lebanon; (C) Intervention site showing superimposition lines on the “roof-site” in Baqa’a camp, Jordan; (R) Superimposition built as a spatial installation.

Through superimposing two camp-scales, a hybrid third is produced, one that can act as an agent for “transferring space and knowledge,” and have the potential to proliferate into a new order of “power relations”.

Images from inside the installation in Baqa’a camp, showing refugees experiencing the new scale and engaging in architectural maps, as well as films documenting camp spaces from the 1970s until today.

2.2. ‘Space of Refuge’ in Burj el-Barajneh Camp, Lebanon, 2016

Map showing the installation site in Burj el-Barajneh camp and scale-superimposition concepts (in colors).

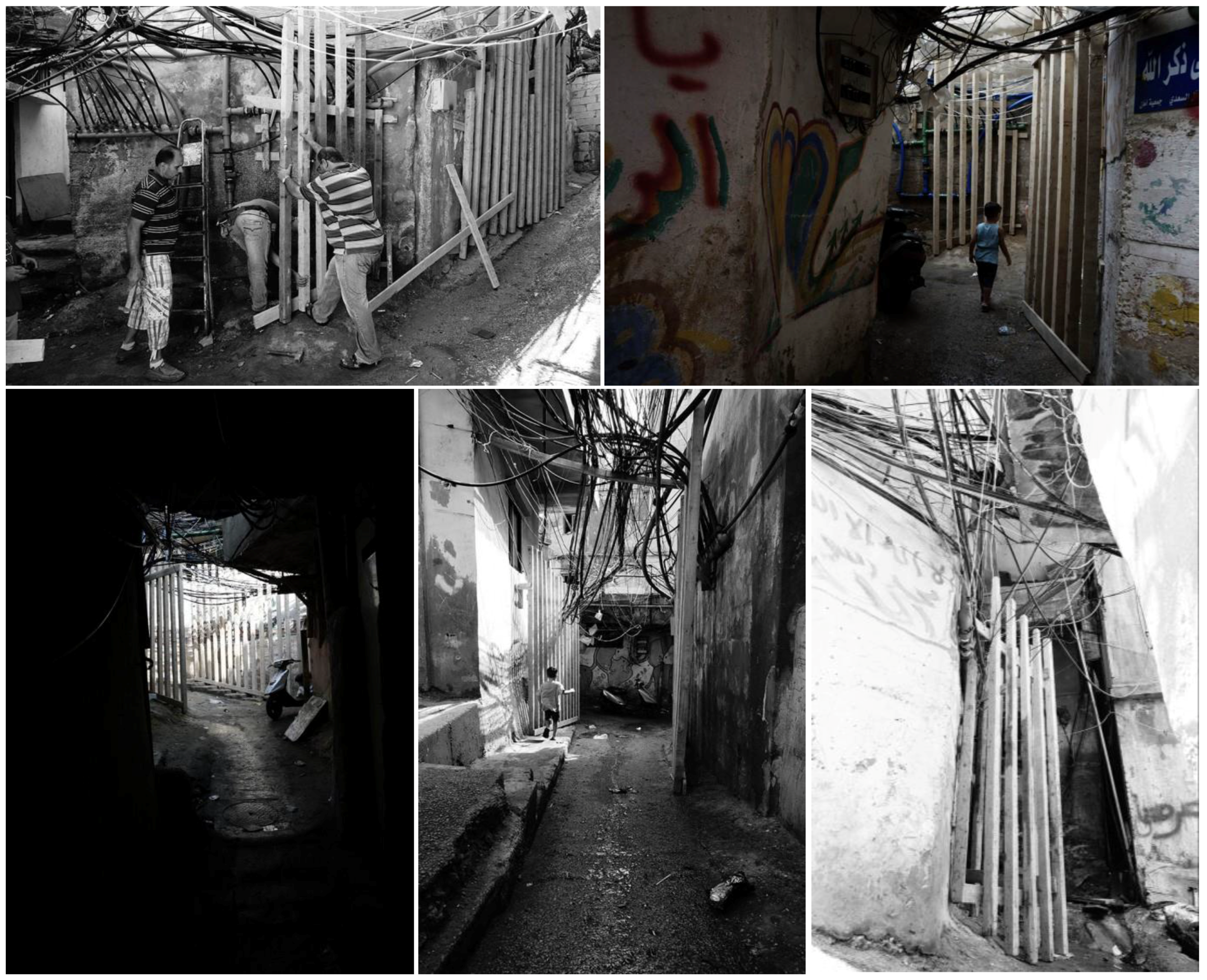

Considering Burj el-Barajneh camp’s highly dense scale, the installation needed to be built on the ground in common areas. In addition, considering its particular spatial history, the approach to scale-superimposition in Burj el-Barajneh camp differed from Baqa’a camp, in that I opted to superimpose three different modes of spatial scales, each with the aim to produce different “scales” of discussion around space, and potentially trigger the existing apparatus to behave alternatively.

The first mode involved extending the existing scale beyond the current spatial threshold, thus questioning the limits of space, while concurrently revealing the ingenious skills the refugees possess in relation to building space within existing limitations;

Mode 1: (L) laying out the installation outline whereby extending the existing scale, (C) Constructing the installation, (R) Installation piece acting as another element within the larger camp-apparatus.

the second mode involved superimposing the first UN scale built inside the camp (demonstrated through the three-by-four-meter UN shelter room) over the existing scale of the camp, so as to clearly demonstrate the historical evolution of space inside the camp;

Mode 2: (L) Constructing the UN shelter room, (R) Shelter room installation in blue (the official UN color) intersecting with the existing spatial fabric causing the blue shelter to be interrupted on all four sides.

and the third mode was an application of a Foucauldian exercise, stacking the existing grid onto itself while applying a “shifting”, to intentionally mask-cover certain areas on the ground and reveal new ones in the form of new, potential space and knowledge.

Mode 3: Images showing the third installation mode which involved stacking the camp grid onto itself while applying a shift to reveal new potential spaces, while the translucent installation material allows the refugee to question this new relationship.

By constructing new scales—in the form of installations—on existing ones, not only is the existing form interrupted, but the existing spatio-movement and circulation are altered as well, forcing the inhabitants to address the intervention as part of their daily inhabitation of the camp.

Image showing the camp inhabitants going about their daily lives while encountering the installations along the way and engaging with them in different ways. Some treat them as another natural element of the camp, while others address them as new operational devices within the camp’s tissue.

Interventions inside a complex and conflictual space—such as those of the camps—acquire various functions and have the potential to adopt numerous subjectivities depending on their localized sociopolitical geography within the camp, as well as the materiality of the spatial network of which they have been inserted. Yet, what remains a common element across different camp geographies is the simultaneous production of space and conflict, a conflict that can become productive—as history shows in the camps—in redefining existing power relations.