The G1000 Firework Dialogue as a Social Learning System: A Community of Practice Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

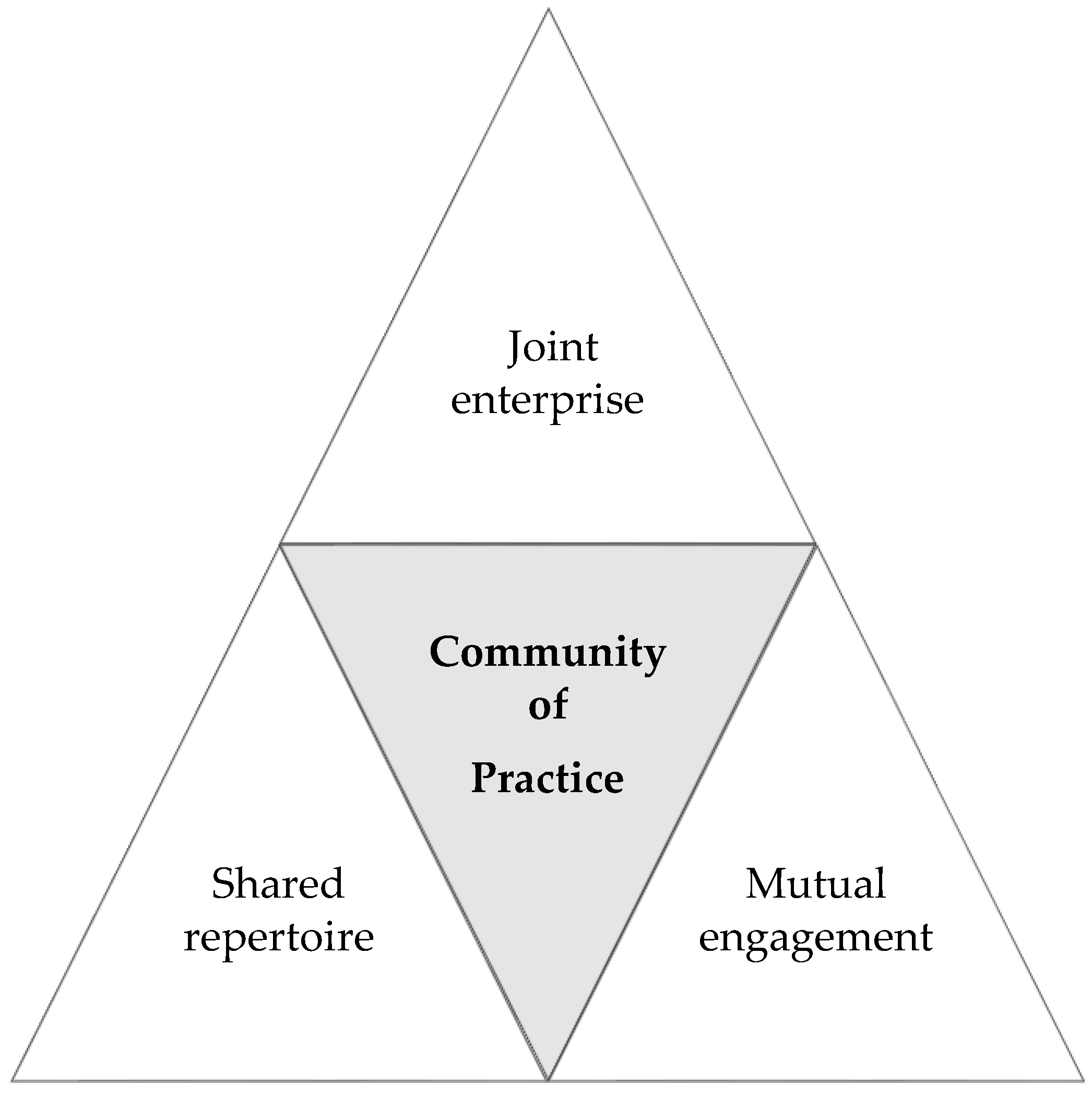

2. Design Requirements for a Citizen Participation Process as a Social Learning System

3. Background to the Case Study and its Methodology

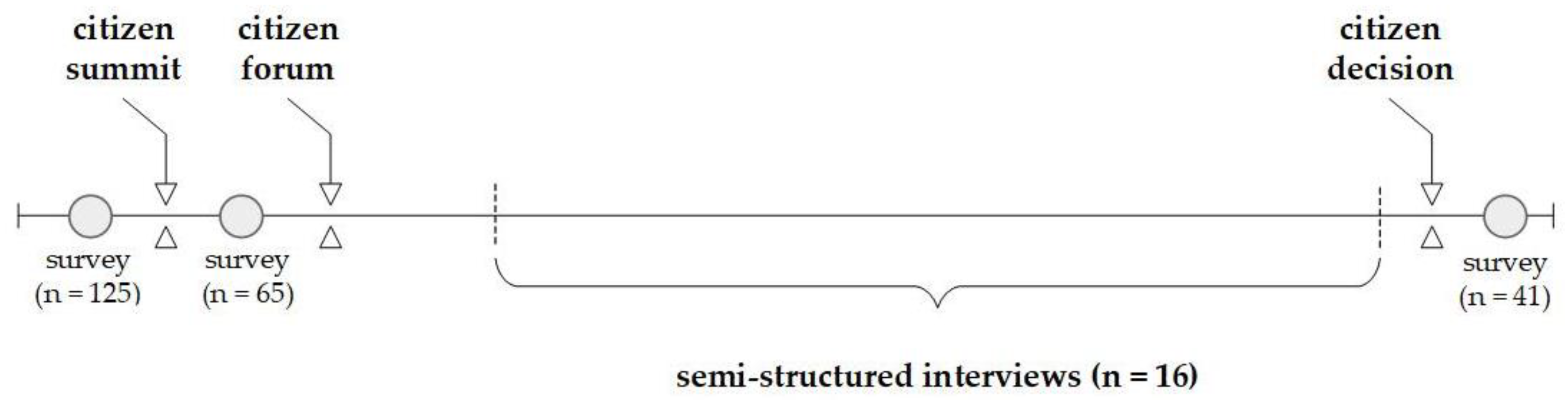

3.1. Case Study Methodology and Ethical Considerations

3.2. Background to the G1000 Initiative(s) in Belgium and The Netherlands

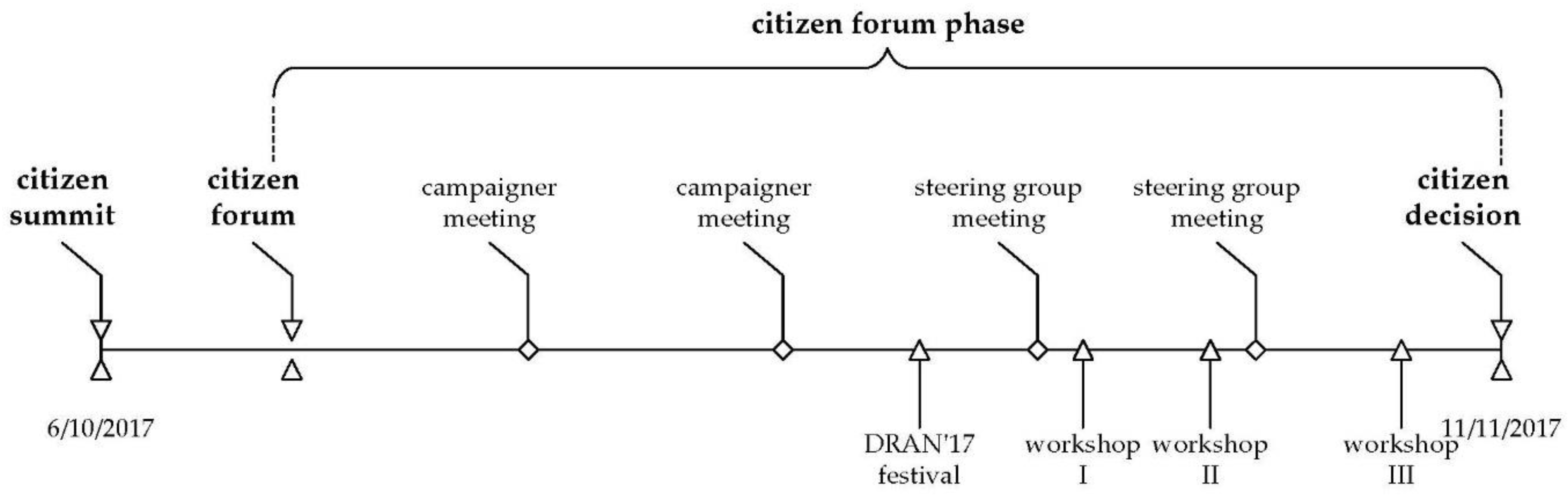

3.3. The G1000 Firework Dialogue in Enschede

4. Results

4.1. G1000 Firework Dialogue as a Social Learning System?

4.1.1. Developing a Sense of a Joint Enterprise

“Yes, everyone contributed in some way to the discussion and we learned a lot from each other [...]. There were also many people at my table who shared personal experiences and from whom you could get life lessons.”(P28: 2017, 18, G1)

“I also liked to hear how those young people view it and why it is so important for them, and why it is so nice for them. But on the other hand I also found it special to hear from the people who are experiencing nuisance, or who are afraid of fireworks, or who have experienced the fireworks disaster.”(P19: 2017, 34, G1)

“It was a nice way to exchange arguments with others, thereby seeing things from a different perspective. I did not think about some aspects beforehand. It was nice that—with some exceptions6—participants equally contributed to the dialogue.”(P27: 2 measurement; 46:46)

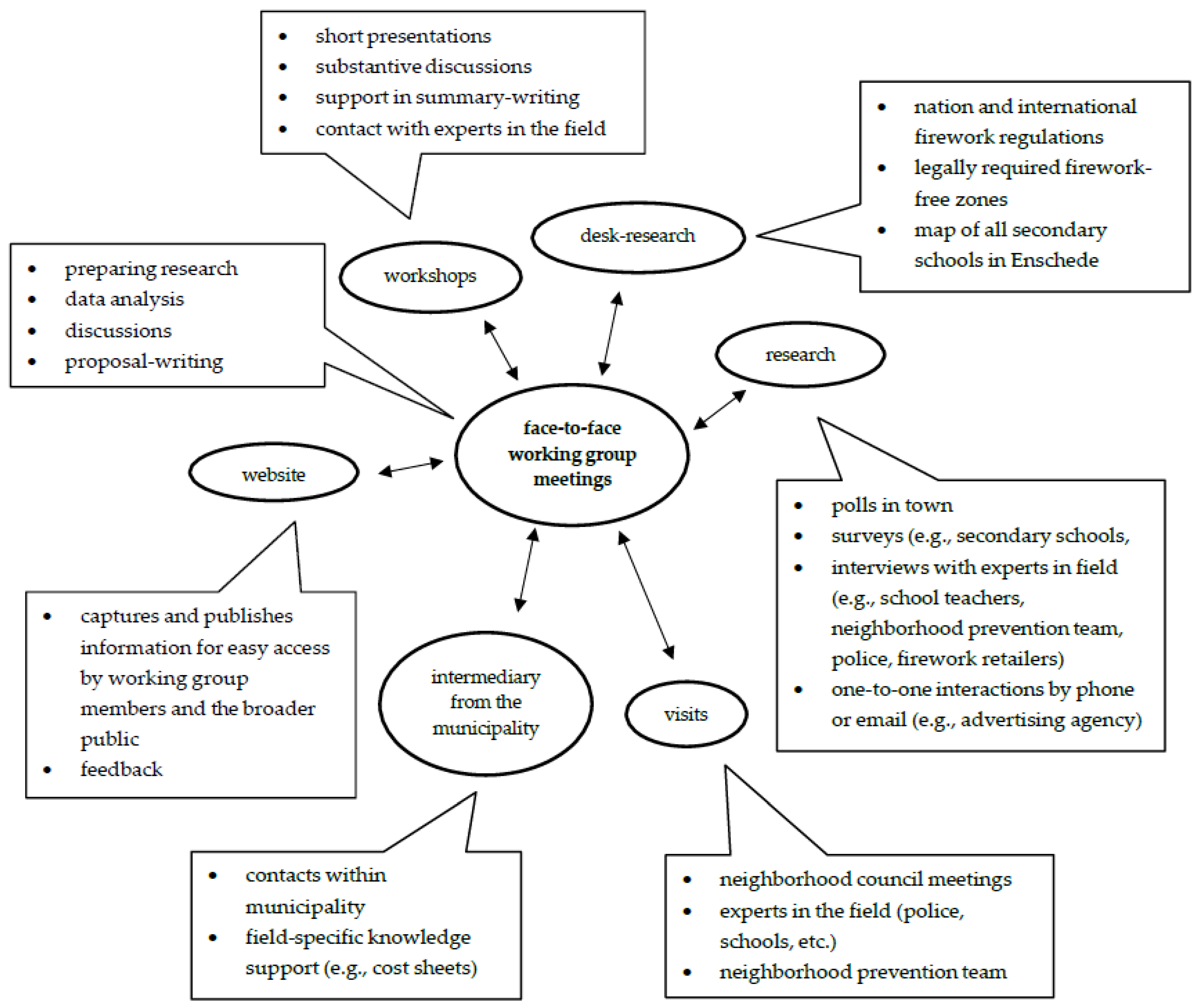

4.1.2. Mutual Engagement and Interaction within Working Groups

“I have contact with [person 1] and [person 2] via a separate WhatsApp group because we act a bit like team leaders, uhm … and with the others, we just have mail contact. If things need to be picked up or worked out, or if we want their opinions, we also mail them. Also, there is one man, I know quite well. I also have a lot of contact with him via WhatsApp and by phone. He is slightly more active than the rest.”(P19: 2017, 34, G1; 203:203)

4.1.3. Establishing Shared Repertoire

4.2. The Overall Effectiveness of the Social Learning Dynamics in the G1000 Firework Dialogue

4.2.1. Factors Constraining Participation and Community Building in the G1000 Firework Dialogue

4.2.2. Perceived Benefits from Participation in G1000 Firework Dialogue

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Code I | Subcode | Code Definition |

| Joint Enterprise (JE) | JE-common_ground_formation | Refers to the extent members follow the same or different ways of reasoning. |

| JE-common_goal | Refers to the extent members aim to achieve a joint goal. | |

| JE-action | Refers to the extent members develop a common purpose for joint action. | |

| JE-level_of_learning_energy | Refers to the extent members get the opportunities to negotiate a joint inquiry and important questions. | |

| JE-task_delegation | Refers to the extent members have a common understanding about who does what. | |

| Code II | Subcode | Code Definition |

| Shared Repertoire (SR) | SR-experience | Refers to the extent members have accumulated common resources (experiences, language, methods, and artefacts) over time that foster potential future interactions. |

| SR-language/jokes | ||

| SR-methods | ||

| SR-artefacts | ||

| Code III | Subcode | Code Definition |

| Mutual Understanding (MU) | MU-nature | Refers to the way members develop shared ways of engaging in doing things together. |

| MU-relationships | Refers to the extent members develop trust and sustained mutual relationships. | |

| MU-information_flow | Refers to the way in which information is exchanged among members. | |

| MU-nature_of_conversations | Refers to the way in which members engage directly in conversations with each other. | |

| MU-problem_solving_capacity | Refers to the extent members are able to raise troubling issues during the discussion. | |

| MU-membership | Refers to the extent there is an overlap in members’ descriptions of who belongs. | |

| MU-personal_contribution | Refers to the extent members know what they can do and how they can contribute to the enterprise. |

References

- Amin, Ash, and Joanne Roberts. 2008. Knowing in action: Beyond communities of practice. Research Policy 37: 353–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, Christopher. 2011. Pragmatist Governance: Re-Imagining Institutions and Democracy. Oxford: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, Hannah. 2010. Truth and politics. In Truth: Engagements Across Philosophical Traditions. Edited by José Medina and David Wood. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 295–314. [Google Scholar]

- Arnstein, Sherry. 1969. A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35: 216–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbie, Earl. 2015. The Practice of Social Research. Boston: Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Bohman, James. 1997. Deliberative democracy and effective social freedom: Capabilities, resources and opportunities. In Deliberative Democracy. Edited by James Bohman and William Rehg. Cambridge: The MIT Press, pp. 321–48. [Google Scholar]

- Caluwaerts, Didier, and Min Reuchamps. 2012. The G1000: Facts, figures and some lessons from an experience of deliberative democracy in Belgium. In The Malaise of Electoral Democracy and What to Do about. Edited by Philippe Van Parijs. Brussels: Re-Bel, pp. 10–33. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, Simone. 2003. Deliberative democratic theory. Annual Review of Political Science 6: 307–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryzek, John. 2000. Deliberative Democracy and Beyond. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Frank. 2000. Citizens, Experts, and the Environment: The Politics of Local Knowledge. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Galli, Francesca, Gianluca Brunori, Francesco Di Iacovo, and Silvia Innocenti. 2014. Co-producing sustainability: Involving parents and civil society in the governance of school meal services. A case Study from Pisa, Italy. Sustainability 6: 1643–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganuza, Ernesto, and Francisco Francés. 2012. The deliberative turn in participation: The problem of inclusion and deliberative opportunities in participatory budgeting. European Political Science Review 4: 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertner, Drew, Joanne Roberts, and David Charles. 2011. University-industry collaboration: A CoPs approach to KTPs. Journal of Knowledge Management 15: 625–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodin, Robert. 2008. Innovating Democracy: Democratic Theory and Practice After the Deliberative Turn. Oxford: OUP. [Google Scholar]

- Grönlund, Kimmo, Setälä Maija, and Kaisa Herne. 2010. Deliberation and civic virtue: Lessons from a citizen deliberation experiment. European Political Science Review 2: 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutmann, Amy, and Dennis Thompson. 2009. Why Deliberative Democracy? Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, Jürgen. 1996. Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Head, Brian, and John Alford. 2015. Wicked problems: Implications for public policy and management. Administration & Society 47: 711–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, Frank, and Ank Michels. 2011. Democracy transformed? Reforms in Britain and The Netherlands (1990–2010). International Journal of Public Administration 34: 307–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, Judith, and David Booher. 2004. Reframing public participation: Strategies for the 21st Century. Planning Theory & Practice 5: 419–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, Judith, and David Booher. 2010. Planning with Complexity: An Introduction to Collaborative Rationality for Public Policy. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ison, Ray. 2012. Traditions of understanding: Language, dialogue and experience. In Social Learning in Environmental Management. Towards a Sustainable Future. Edited by Chris Blackmore. London: Springer, pp. 39–57. [Google Scholar]

- Lovan, Robert, Miachael Murray, and Ron Shaffer. 2017. Participatory Governance: Planning, Conflict Mediation and Public Decision-Making in Civil Society. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Luskin, Robert C., James S. Fishkin, and Roger Jowell. 2002. Considered opinions: Deliberative polling in Britain. British Journal of Political Science 32: 455–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manin, Bernard. 1987. On legitimacy and political deliberation. Political Theory 15: 338–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, Kate, and Paul Benneworth. 2018. The construction of new scientific norms for solving Grand Challenges. Palgrave Communications 4: 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulaert, Frank, Erik Swyngedouw, Flavia Martinelli, and Sara Gonzalez. 2010. Can Neighbourhoods Save the City?: Community Development and Social Innovation. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Muro, Melanie, and Paul Jeffrey. 2006. Social Learning—A Useful Concept for Participatory Decision-Making Processes? Cranfield: School of Water Sciences, Cranfield University. [Google Scholar]

- Neyer, Jürgen. 2006. The deliberative turn in integration theory. Journal of European Public Policy 13: 779–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, Jules. 1995. Participatory learning for sustainable agriculture. World Development 23: 1247–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, Mark. 2008. Stakeholder participation for environmental management: A literature review. Biological Conservation 141: 2417–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, Lena, Sjoerd Zwart, Michael Lynch, and Israel-Jost Vincent. 2014. Science after the Practice Turn in the Philosophy, History, and social Studies of Science. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Graham. 2009. Democratic Innovations: Designing Institutions for Citizen Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Patrick, and Maureen McDonough. 2001. Beyond public participation: Fairness in natural resource decision making. Society & Natural Resources 14: 239–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, Vanessa. 2014. Co-production and collaboration in planning—The difference. Planning Theory & Practice 15: 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, Etienne. 1998. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, Etienne. 2000. Communities of practice and social learning systems: The career of a concept. In Social Learning in Environmental Management. Towards a Sustainable Future. Edited by Chris Blackmore. London: Springer, pp. 179–98. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, Etienne. 2011. Communities of Practice: A Brief Introduction. Available online: https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/xmlui/handle/1794/11736 (accessed on 15 June 2018).

- Woodhill, Jim. 2010. Sustainability, social learning and the democratic imperative: Lessons from the Australian Landcare movement. In Social Learning in Environmental Management. Towards a Sustainable Future. Edited by Chris Blackmore. London: Springer, pp. 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Robert. 2009. Case Study Research, Design & Methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Inter-coder reliability of 96 percent. |

| 2 | For example, the G1000 was nominated for the “Prijs voor de Democratie” (in Engl. “Award for Democracy”) in 2011. |

| 3 | The term closing meeting (in Dutch: “slotbijeenkomst”) was also often interchangeably used when referring to the final event. For consistency reasons, the authors, however, have decided to adopt the Platform G1000 terminology. |

| 4 | The amount of people at each table varied between 4 and 8 people during morning and afternoon sessions. |

| 5 | Some interviewees indicated that they thought prior to the citizens’ summit event that the topic would attract predominantly supporters and opponents of fireworks. |

| 6 | A few interviewees indicated that they felt disturbed by some dialogue partners who either deviated too much from the topic to tell their personal story or took the floor to defend their position on the matter. |

| 7 | E.g., developing and conducting interviews, surveys, opinion pools among students, experts in the field, and fellow citizens; doing desk-research, or developing first ideas for an app. |

| 8 | The app group was dissolved and participants merged with members of the awareness-raising group. The firework show working group dissolved and members merged with the working group on firework(-free) zones. |

| 9 | A participant mentioned that he cancelled another meeting for a meeting with his working group. |

| 10 | Many participants indicated that after the first workshops the process became more clear. |

| 11 | In order to warrant representativeness of the participation process, only people who were randomly selected and received a formal invitation were allowed to participate in the G1000 firework dialogue. |

| 12 | Some participants were angry with the municipality, since it shared a local newspaper article after the citizens’ summit via its official website in which it was wrongly stated that citizens from Enschede had chosen for a firework show. |

| 13 | E.g., some working groups faced difficulties with printing and organising rooms during the summer holiday period. |

| Characteristic | Indicators | Question |

|---|---|---|

| Joint enterprise | Common goal; common ground formation; joint action; task delegation; learning energy | Do group members share a common purpose, which provides them with a joint goal for (joint) actions? Do group members develop a shared sense of responsibility to share information? |

| Mutual engagement | Relationship building; information flow; nature of conversations; identity building | What events and interactions weave the community and develop trust? Does this result in an ability to negotiate the meaning of a group’s culture and its practices? |

| Shared repertoire | Development of routines and common ways of working | To what extent have shared experience, language, artefacts, histories, and methods accumulated over time and with what potential for future interactions and new means? |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eckardt, F.; Benneworth, P. The G1000 Firework Dialogue as a Social Learning System: A Community of Practice Approach. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7080129

Eckardt F, Benneworth P. The G1000 Firework Dialogue as a Social Learning System: A Community of Practice Approach. Social Sciences. 2018; 7(8):129. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7080129

Chicago/Turabian StyleEckardt, Franziska, and Paul Benneworth. 2018. "The G1000 Firework Dialogue as a Social Learning System: A Community of Practice Approach" Social Sciences 7, no. 8: 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7080129