Misalignment of Career and Educational Aspirations in Middle School: Differences across Race, Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Status

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data

3.2. Measures

3.3. Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Philip Oreopoulos, and Uros Petronijevic. “Making College Worth It: A Review of Research on the Returns to Higher Education.” Working Paper 19053. Cambridge, MA, USA: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2013. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w19053.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2016).

- Patricia C. Gandara, and Frances Contreras. The Latino Education Crisis: The Consequences of Failed Social Policies. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mark Hugo Lopez. Latinos and Education: Explaining the Attainment Gap. Washington: Pew Hispanic Center, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Barbara L. Schneider, and David Stevenson. The Ambitious Generation: America's Teenagers, Motivated but Directionless. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kimberly A. Goyette. “College for Some to College-for-All: Social Background, Occupational Expectations, and Educational Expectations over Time.” Social Science Research 37 (2008): 461–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeremy Staff, Angel Harris, Ricardo Sabates, and Laine Briddell. “Uncertainty in early occupational aspirations: Role exploration or aimlessness? ” Social Forces 89 (2010): 659–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenneth B. Kidd. “Book Review. The Ambitious Generation: America’s Teenagers, Motivated but Directionless.” American Journal of Education 108 (1999): 63–67. [Google Scholar]

- Stephen L. Morgan, Theodore S. Leenman, Jennifer J. Todd, and Kim A. Weeden. “Occupational plans, beliefs about educational requirements, and patterns of college entry.” Sociology of Education 86 (2013): 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricardo Sabates, Angel L. Harris, and Jeremy Staff. “Ambition Gone Awry: The Long Term Socioeconomic Consequences of Misaligned and Uncertain Ambitions in Adolescence.” Social Science Quarterly 92 (2011): 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarah Schmitt-Wilson, and Caitlin Faas. “Alignment of Educational and Occupational Expectations Influences on Young Adult Educational Attainment, Income, and Underemployment.” Social Science Quarterly, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher Jencks. Inequality: A Reassessment of the Effect of Family and Schooling in America. New York: Basic Books, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Grace Kao, and Jennifer S. Thompson. “Racial and ethnic stratification in educational achievement and attainment.” Annual Review of Sociology 29 (2003): 417–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William H. Sewell, Archibald O. Haller, and Alejandro Portes. “The educational and early occupational attainment process.” American Sociological Review 34 (1969): 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susan A. Dumais. “Cultural Capital, Gender, and School Success: The Role of Habitus.” Sociology of Education 75 (2002): 44–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre Bourdieu, and Jean-Claude Passeron. Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture, 2nd ed. London: Sage, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Alice Sullivan. “Bourdieu and Education: How useful is Bordieu’s theory for researchers? ” The Netherlands' Journal of Social Sciences 38 (2002): 144–66. [Google Scholar]

- Eric Grodsky, and Melanie T. Jones. “Real and imagined barriers to college entry: Perceptions of cost.” Social Science Research 36 (2007): 745–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabrina Zirkel. “Is there a place for me? Role models and academic identity among White students and students of color.” The Teachers College Record 104 (2002): 357–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn D. Israel, Lionel J. Beaulieu, and Glen Hartless. “The Influence of Family and Community Social Capital on Educational Achievement.” Rural Sociology 66 (2001): 643–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay MacLeod. Ain’t No Makin’ It: Aspirations and Attainment in a Low-Income Neighborhood. Boulder: Westview, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Susan Auerbach. “Engaging Latino parents in supporting college pathways: Lessons from a college access program.” Journal of Hispanic Higher Education 3 (2004): 125–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gary D. Sandefur, Ann M. Meier, and Mary E. Campbell. “Family resources, social capital, and college attendance.” Social Science Research 35 (2006): 525–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert G. Gonzalez. Chicano Education in the Era of Segregation. Denton: University of North Texas Press, 2013, vol. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Constance M. Yowell. “Dreams of the future: The pursuit of education and career possible selves among ninth grade Latino youth.” Applied Developmental Science 6 (2002): 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catherine R. Cooper, Jill Denner, and Edward M. Lopez. “Cultural brokers: Helping Latino children on pathways toward success.” The Future of Children 9 (1999): 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doris R. Entwisle, and Karl L. Alexander. “Entry into school: The beginning school transition and educational stratification in the United States.” Annual Review of Sociology 19 (1993): 401–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George L. Wimberly, and Richard J. Noeth. “College Readiness Begins in Middle School. ACT Policy Report.” 2005. Available online: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED483849.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Mari Luna De La Rosa, and William G. Tierney. “Breaking through the Barriers to College: Empowering Low-Income Communities, Schools, and Families for College Opportunity and Student Financial Aid.” 2006. Available online: http://www.usc.edu/dept/chepa/pdf/Breaking_through_Barriers_final.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2016).

- Monica Martinez, and Shayna Klopott. The Link between High School Reform and College Access and Success for Low-Income and Minority Youth. Washington: American Youth Policy Forum, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Julia Bryan, Cheryl Holcomb-McCoy, Cheryl Moore-Thomas, and Norma Day-Vines. “Who sees the school counselor for college information? A national study.” Professional School Counseling 12 (2009): 280–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick T. Terenzini, Alberto F. Cabrera, and Elena M. Bernal. Swimming against the Tide. New York: College Board, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Christina Boelter, Tanja Link, Brea L. Perry, and Carl Leukefeld. “Diversifying the STEM pipeline: Implications from a science intervention for underserved youth.” Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk 20 (2015): 218–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Employment Projections. Education and Training Assignments by Detailed Occupation, 2014. ” Available online: http://www.bls.gov/emp/ep_table_112.htm (accessed on 31 May 2016).

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Employment Projections. Education and Training Data Definitions. ” Available online: http://www.bls.gov/emp/ep_nem_definitions.htm#education (accessed on 31 May 2016).

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 146 | 58.6 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White (not Latino) | 99 | 39.8 |

| Black | 86 | 34.5 |

| Latino | 23 | 9.2 |

| Asian | 24 | 9.6 |

| Other | 17 | 6.8 |

| Free/reduced lunch | 139 | 55.8 |

| Neither parent college-educated | 58 | 23.3 |

| Educational aspiration | ||

| High school | 9 | 3.6 |

| Associate’s degree | 26 | 10.4 |

| Bachelor’s degree or more | 214 | 85.9 |

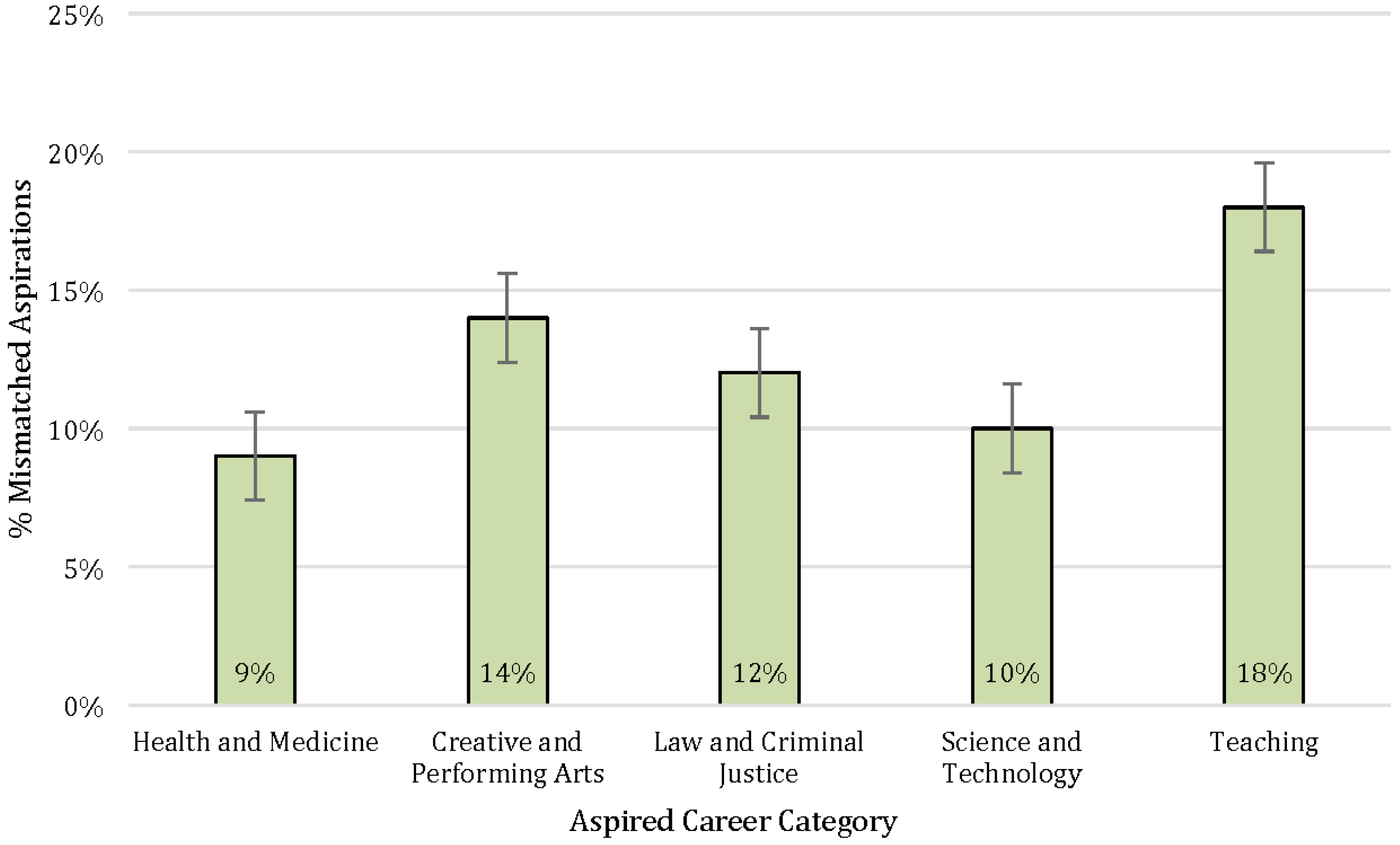

| Career aspiration (field) 1 | ||

| Health and medicine | 82 | 32.9 |

| Creative and performing arts | 50 | 20.1 |

| Law and criminal justice | 44 | 17.7 |

| Science and technology | 70 | 28.1 |

| Teaching | 20 | 8.0 |

| Career educational requirement | ||

| High school | 37 | 14.9 |

| Associate’s degree | 10 | 4.0 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 75 | 30.1 |

| Advanced degree | 127 | 51.0 |

| Mismatched requirements and aspirations | 26 | 10.4 |

| College Aspiring | College Required | Mismatch | X2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Gender | 0.10 | |||

| Female | 128 (87.7) | 122 (83.6) | 16 (11.0) | |

| Male | 86 (83.5) | 80 (77.7) | 10 (9.7) | |

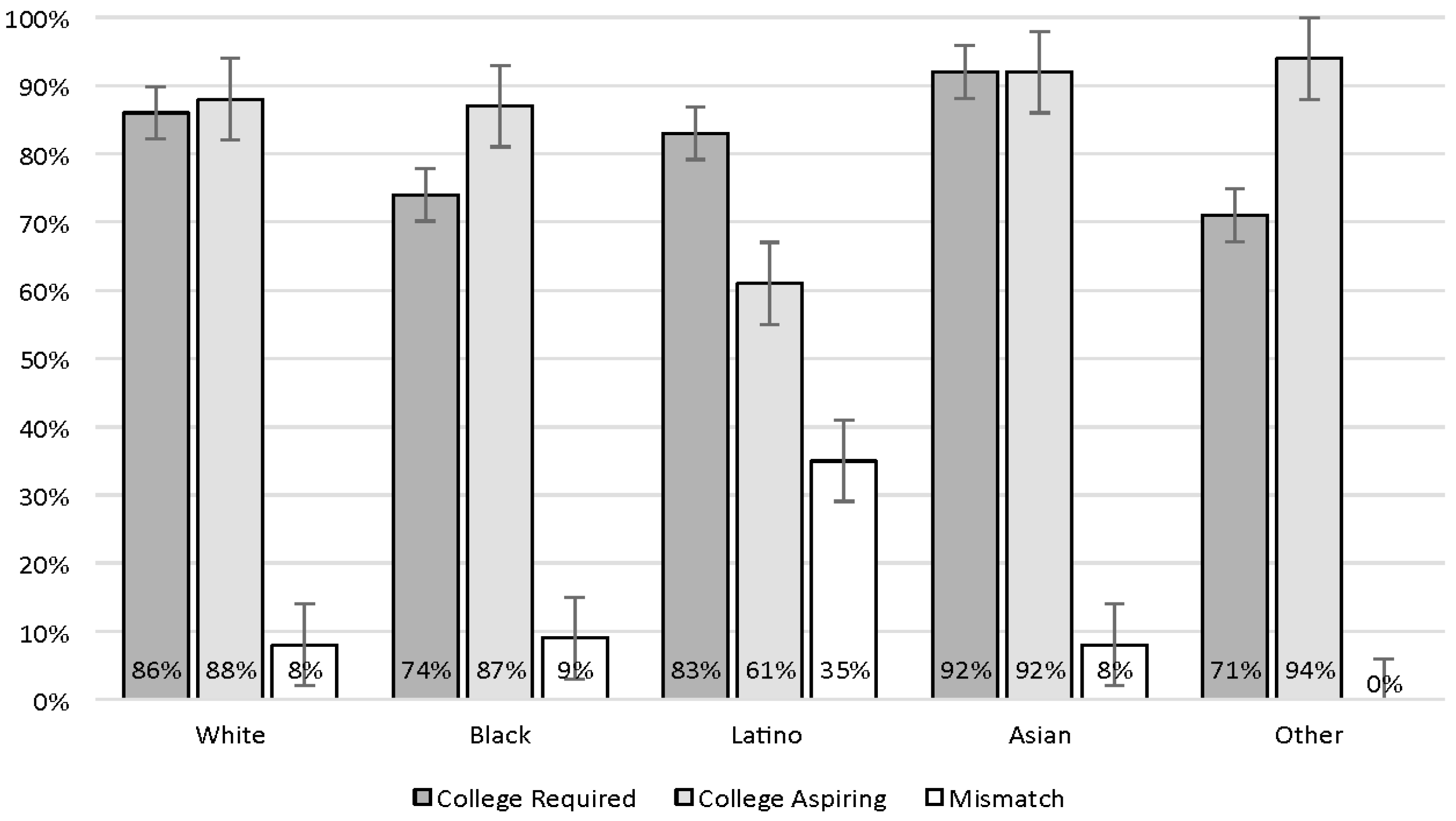

| Race/ethnicity | 17.38 ** | |||

| White (not Latino) | 87 (87.9) | 85 (85.9) | 8 (8.1) | |

| Black | 75 (87.2) | 64 (74.4) | 8 (9.3) | |

| Latino | 14 (60.9) | 19 (82.6) | 8 (34.8) | |

| Asian | 22 (91.7) | 22 (91.7) | 2 (8.3) | |

| Other | 16 (94.1) | 12 (70.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Socioeconomic status | 7.33 ** | |||

| Free/reduced lunch | 111 (79.9) | 108 (77.7) | 21 (15.1) | |

| Paid lunch | 103 (93.6) | 94 (85.5) | 5 (4.6) | |

| Parents’ education | 9.31 ** | |||

| No parent college educated | 44 (75.9) | 48 (82.8) | 12 (20.7) | |

| One or more college educated | 169 (89.4) | 152 (80.4) | 13 (6.9) |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Perry, B.L.; Martinez, E.; Morris, E.; Link, T.C.; Leukefeld, C. Misalignment of Career and Educational Aspirations in Middle School: Differences across Race, Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Status. Soc. Sci. 2016, 5, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci5030035

Perry BL, Martinez E, Morris E, Link TC, Leukefeld C. Misalignment of Career and Educational Aspirations in Middle School: Differences across Race, Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Status. Social Sciences. 2016; 5(3):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci5030035

Chicago/Turabian StylePerry, Brea L., Elizabeth Martinez, Edward Morris, Tanja C. Link, and Carl Leukefeld. 2016. "Misalignment of Career and Educational Aspirations in Middle School: Differences across Race, Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Status" Social Sciences 5, no. 3: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci5030035