1. Introduction

Ours is a judicial tradition defined by two basic pillars: legal positivism in interpreting laws and the law, and an institutional corporatism (not in a derogatory sense) that makes the system close in on itself and seek a self-legitimising discourse.(…) The citizen should be at the centre of the system, yet this is not the case in a system imbued with a positivist and authoritarian vision that is centred on the court and the judge, with the citizen appearing to enter from the outside as the beneficiary. The independence of the courts, viewed as sacred in a state based on the rule of law, is a right of citizens and a duty of the courts (Laborinho Lúcio, Público, 29 January 2007).

The global expansion of judicial power (see

Tate and Vallinder 1995) has triggered a phase of renewed attention to, and reflection on, the role that justice—embodied by the courts, including judges and now Public Prosecutors as well—plays in redefining the balance of the powers of states and on its relevance for the consolidation of democratic systems. In his analysis of a democratic system’s multiple dimensions, John T.

Ishiyama (

2012) views the configuration and conformation of judicial power as extremely important for the balance required by a territorial distribution of powers. In Ishiyama’s words,

the choice of judicial and territorial institutions is a crucial decision for any developing political system. How executive and legislative power is checked is an important consideration in constitutional design. Judiciaries are held out as the best check against the political excesses of other branches of government, but there remains considerable debate over how independent and/or how active an unelected (and for some critics, an unaccountable) branch of government should be in shaping policies and laws. Others, as we have seen, have argued that only through an empowered judiciary can democracy be promoted and consolidated.

An independent judiciary, exercised by its professionals regardless of how their careers are structured, is a fundamental principle to ensure that, in the complex balance of Montesquieu’s old concept of the three state powers, citizenship rights are fully respected and a democratic system’s basic principles are fully guaranteed. However, the implementation and sustainability of the principle does not depend on the judiciary alone, given that its performance is limited by the resources and laws put at its disposal by the other branches of government. This is a historical limitation, and there appears to be no alternative model in sight through which it can be overcome. What is more, given the growing financial and economic crises of Western states, including those felt in the European Union and Portugal in particular

1, a continuation of, and increase in, the existing tensions between the various holders of the different sovereign bodies are only to be expected.

The desired stability of the judiciary became all the more difficult to achieve once the courts and their protagonists ceased to be untouched by any interaction or removed from the dangers of influence-mongering, particularly considering that historically they had been of little relevance in that they tended not to interfere with the established interests and powers of the state and society in general. It was not until the judiciary began extending its reach that the tensions between judicial power on the one hand and the executive and legislative powers on the other grew to alarming proportions, with the first signs occurring in the 1980s. Thus, the judiciary went from a purely symbolic relevance to clear preponderance as far as public powers and democratic legality were concerned. In turn, this transformation brought turbulence and instability to the functioning of the courts, causing the judicial paradigm to change in ways for which its practitioners were, and appear to continue to be, unprepared. It is the obligation of all researchers in the areas of the sociology of law and justice to contribute to an overall reflection on the transformations occurring in the domain of justice, with the aim of providing support for the establishment of justice-related public policies at the local level.

A reflection on the role and importance of the judiciary will have to go beyond existing models or the mere study of the profession, which historically has received the most attention on account of its centrality with regard to judicial power—that of judges. Hence the need for an analysis of the Public Prosecution Service, another key actor within judicial systems these days. Regardless of the differences from one model to another or the competences under consideration, the Public Prosecution Service has become more and more prominent in the context of judicial power across countries. But in spite of their increasing importance, notably as far as prosecution is concerned, and contrary to what has been the case with judges and even lawyers in the past, Public Prosecutors have not yet achieved a consensual status, in terms of either their functions or their competences. Notwithstanding their rise to wide prominence over recent years, Public Prosecutors are still a relatively unknown judicial actor in the eyes of most citizens, especially where their attributions go beyond the realm of prosecution, as is the case in many countries, Portugal included.

Although there is a tendency at the international level to provide the Public Prosecution Service with greater autonomy of action, there are still many models in which hierarchical or functional dependence on governments, marked by varying degrees of transparency or controversy, is common practice. In other models, autonomy and the safeguards in place for ensuring that it is exercised with fairness are conducive to an increase in the capacity to act, alongside greater internal and external accountability that result from evaluation and monitoring and from greater public exposure, respectively. As part of the judiciary, Public Prosecutors are also participants in the global processes of judicial reform that are currently taking place with differing levels of intensity through the action of international bodies (

Santos 2002a,

2002b), whether comprised by states—such as the United Nations Organisation, the European Union, the Council of Europe or MERCOSUR, among others—or associations—such as the International Union of Magistrates, the Association of European Magistrates for Democracy and Freedoms, or the International Association of Prosecutors. Still the effects of globalisation in the area of justice show a discrepancy between the way in which laws are being rapidly harmonised, particularly in the fields of economy and trade, and the difficulties in finding a consensus with respect to the existing models of judicial organisation across countries. While the former may be the result of a high-intensity globalisation produced by supranational bodies such as those mentioned above, the latter has all the trappings of a low-intensity globalisation generated by the combined actions of various national actors belonging to international organisations (

Santos 1997;

1999;

2001, p. 90).

Public Prosecutors have not received much attention from international, suprastate, state and/or associative institutions in terms of seeking to influence the adoption of a common organisational model by the most diverse countries

2. What we have is mainly the approval, at different moments, of guiding principles for the exercise of functions—primarily of judges, but also, since the late 1980s, of Public Prosecutors—with special emphasis on issues of autonomy and impartiality regarding their competences and the conditions in which prosecution is carried out. However, in countries such as Portugal, Public Prosecutors exercise a wide range of competences in the various legal areas, a fact that turns them into key actors in the context of evaluating the performance of the judicial system and when efforts are made to improve its functioning, even in the midst of financial constraints that hinder any state funding of the investments required by the judicial reforms.

This is the backdrop to the present article, which stems from the need to discuss the functioning of the Public Prosecution Service and its professional practices, promoting the circulation of ideas and solutions for possible judicial reforms in the model currently in force in Portugal. It is not a question of looking for the “perfect model” or of trying to achieve an “ideal synthesis,” but rather of highlighting the main aspects that can contribute to the defence of legality and the promotion of access to law and justice through the action of Public Prosecutors. In order to achieve such a goal, it is necessary for Public Prosecutors to assume a new paradigm, proactively centred on the defence of citizenship rights.

The main objective, based on previous writings by the present author and other relevant sources, is to answer a question that is both simple and difficult: can Public Prosecutors build their profession around the citizen and do it in a proactive manner? By answering this question, we will promote a discussion and reflection on the identity, competences and professional performance of Portugal’s Public Prosecutors or magistrates

3, in a context of major transformations in the judicial systems and in the legal professions themselves, both as key actors and as promoters of citizens' access to law and justice in the various legal areas in which they are active participants. The aim of this article is thus to analyse, on the one hand, the way in which Public Prosecutors exercise their multiple competences with regard to their relation to citizens and their intermediary role between the courts and the various entities and professions, both public and private, that act on behalf of citizens’ rights, and, on the other hand, the proactive potential of that exercise.

2. Public Prosecution in Portugal: Functions, Organisation and Numbers

Public Prosecutors in Portugal always had a vast, heterogeneous and transversal set of attributes and competencies providing them a polymorphic nature. According to Gomes Canotilho and Vital Moreira (

Canotilho and Moreira 1993, p. 830), the functions of Public Prosecutors can be grouped into four areas: ‘representing the state, namely in the courts, in the proceedings in which they are involved, acting as a type of state lawyer; instituting criminal proceedings (...); defending democratic legality, intervening in administrative and fiscal litigation amongst other areas, and monitoring constitutionality; defending the interests of certain persons who have a greater need for protection, namely, after ascertaining certain requirements, children, absent individuals, workers, etc.’

The Law n° 60/98 of 27 August, which first appeared as the Public Prosecutors’ Statute (PPS) following the 1997 Constitutional Review, introduced a new definition of Public Prosecutors, according to which ‘Public Prosecutors represent the State, defend the interests determined by law, take part in conducting criminal policy as defined by the sovereign bodies of the state, exercise penal action guided by the principle of legality, and defend democratic legality, in accordance with the terms of the Constitution, this Statute and the law’ (Article 1, nr. 1).

Under the terms of the PPS, Public Prosecutors are entrusted with the following responsibilities: representing the state, the Autonomous Regions, local authorities, persons lacking legal capacity, and persons who are unknown or whose whereabouts are unknown; applying criminal policy as defined by the sovereign bodies of the state; instituting criminal proceedings guided by the principle of legality; officially representing workers and their families, defending their social rights; defending various collective interests under the terms prescribed by law; defending the independence of the courts within the scope of their duties and ensuring that jurisdictional functions are conducted in accordance with the Constitution and the law; ensuring that the court decisions they are legitimately allowed to promote are implemented; directing criminal investigations, even if conducted by other bodies; producing and implementing crime prevention measures; monitoring the constitutionality of normative acts; intervening in bankruptcy and insolvency cases and in all cases involving the public interest; consultancy work; monitoring the procedural work of criminal police organisations; appealing whenever a decision results from collusion between the parties for the purpose of defrauding the law or with the intention of breaking the law; any other functions conferred on them by law (cf. Article 3). In summary, Public Prosecutors perform their duties into five major legal areas: criminal (where they are responsible for coordinating all the investigation until the promotion of the accusation), civil, labour, family and administrative.

These duties are also mentioned in procedural law and other legislation. Public Prosecutors can intervene as principals or as accessory parties, depending on whether they represent or are the main representative of the party or whether their role is merely to safeguard the interests attributed to them by law. It can therefore be concluded that in addition to being transversal to the entire process, the work of Public Prosecutors also involves specific functions in which they are sometimes the plaintiff and at other times the defendant or even amicus curiae (

Dias et al. 2008).

Public Prosecutors have a hierarchical structure and organisation, although their professionals have autonomy on the execution of their functions. On the top, the Prosecutor-General, the head of the Public Prosecution Service, followed by: The General Prosecutors’ Adjuncts—on the name of the Prosecutor-General—working on higher courts (Supreme Courts of Justice and Administrative and Accounting Court); the General Prosecutors’ Adjuncts working on Appeal Courts (second instance); and Prosecutors and Prosecutors’ Adjuncts working on lower courts. Public Prosecutors are placed in specialised courts/sections, according to the law of organisation of the judicial system (Law no 62/2013 of 26th August). Portuguese judicial system is currently organised into three main structures: (a) Lower Courts, which included specialised sections on criminal, civil, family, labour, execution of sentences and commerce; (b) Appeal Courts, with specialised section on criminal, civil, social issues, family and commerce; (c) Supreme Court of Justice, also with the same specialised sections as the Appeal Courts. Portugal has a parallel structure of courts for administrative and tax issues, where Public Prosecutors also execute their functions on these matters, with a similar organisation.

The number of Public Prosecutors working on all the courts were, on 31 December 2016, 1501 (in judicial and administrative courts), divided into the several categories described above. According to statistics produced by the General-Directorate of Justice of the Ministry of Justice, there were 629,369 files involving the intervention of Public Prosecutors in 2016, which provides a gross average of 419.3 files per Public Prosecutor (these numbers includes all areas of actuation, although the criminal area remains the major area of Public Prosecutors).

3. The Public Prosecution Service as Part of the System of Access to Law and Justice

Over the years, access to law and justice has been primarily viewed as an important resource of political discourse and not so much as an active policy endowed with legal, concrete means. This can be seen in the scant “attention” paid to this field by Portugal’s successive government programmes, even though it has been a priority since the late 1990s. It has become a politically sensitive topic with major financial implications but little practical results in terms of system improvement. As a consequence, some of the reforms introduced in the course of the last two decades, during which time Portuguese governments had to deal with harsh budgetary constraints, have basically sought to control financial costs under the pretence of noble motives, which led to even greater difficulties for citizens.

The successive changes that have taken place since the beginning of the last decade have often been introduced without any consideration of their likely impact and of the need to bring the system to stability before it could function according to expectations. In fact, the implementation of all those transformations over the years does not even lend itself to proper analysis, given that no comprehensive assessments have been made. The report of the Monitoring Commission and the Ministry of Justice’s (

CASAD 2009) audit of legal aid, for example, focused primarily on the financial cost of the system for accessing law and justice, thus devaluing, or at best omitting any mention of, the impact of their implementation in terms of enforcing citizens’ rights and of citizens’ potential difficulties in obtaining legal aid for lack of financial means.

Citizens' access to law and justice has to do with multiple factors, not all of them attributable to the law, the legal professionals or the functioning of the judicial system as a whole (

Pedroso et al. 2003a,

2003b). Among the non-judicial factors greatly affecting a citizen’s access to the law, there are a few that are worth mentioning, such as one’s qualifications, geographic location (where citizens live and judicial services happen to be located), income and socio-economic level, as well as one’s familiarity with the workings of the judicial system or the extent to which courts are known and used. To these, Boaventura de Sousa

Santos (

2011) adds a few equally important factors, such as “(…) prior experience, the gravity of the interests or rights being violated, a thorough cost-benefit assessment, the financial capacity it takes to bear the direct and indirect costs of going to court (including legal costs, lawyers and expert fees, the availability of time, the emotional strain in the presence of professionals, the parlance, buildings especially designed to create distance, etc.)” (

Santos 2011, p. 113).

In a number of studies carried out at the Permanent Observatory of Justice of the Centre for Social Sudies of the University of Coimbra (

Santos et al. 1996;

Pedroso et al. 2002;

Santos and Gomes 2006;

Ferreira et al. 2007;

Dias 2013a,

2015), the workload of the Public Prosecution Service stands out not just in terms of quantity but first of all in terms of quality, and this fact has strengthened the importance of the Service’s role in areas of increasing social sensitivity.

In addition to procedural intervention, the Public Prosecution Service offers the wider public a counselling or guidance service

4 (front-office service). This is a relevant part of its activities, as will be shown below. But it should be pointed out that this role is carried out in conjunction with other institutions that provide information and legal counselling in the various areas of intervention. Just to give an example, that is the case with the area of labour, where, according to António Casimiro Ferreira, there are at present in the sphere of the state (IDICT/IGT—Institute for the Development and Inspection of Working Conditions/Inspectorate-General for Labour, CITE—Commission for Equality in Labour and Employment, and the Public Prosecution Service), in the private sector (lawyers, solicitors and other legal professions) and in the wider community (trade union organisations and various other associations) a considerable variety of options with regard to the demand for labour-related information and legal counselling (

Ferreira 2005a, p. 404;

2005b).

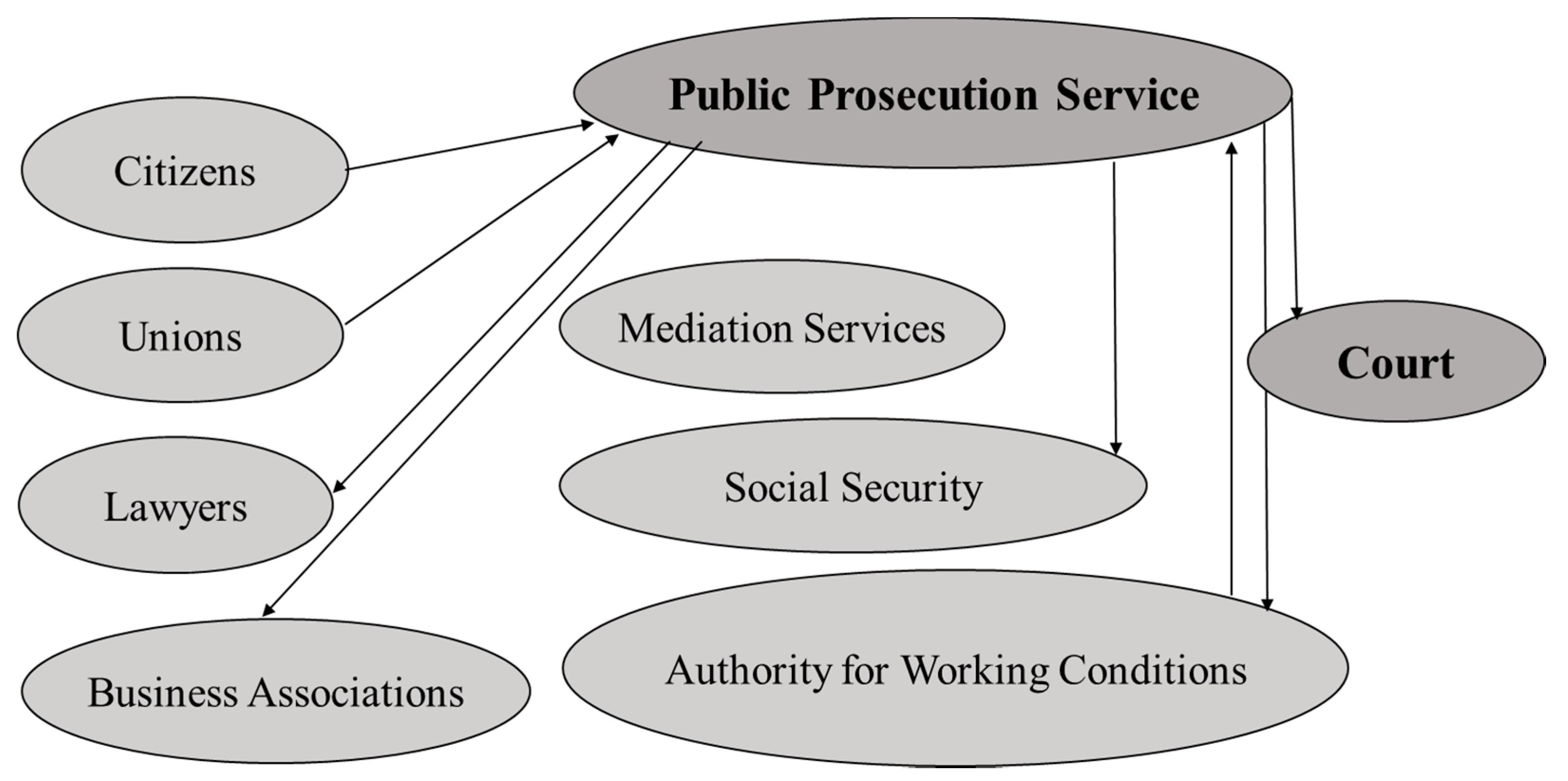

The figure below seeks to illustrate and operationalise, albeit in a relatively simplified manner, the role of the Public Prosecution Service in respect of its intervention in matters pertaining to labour justice, so as to highlight the intermediary nature of its work. The same exercise is put forward for the remaining legal areas in

Dias (

2013a;

2013b), as part of a wider contribution towards a more complex a more complex, interactive representation of the role of Portugal’s Public Prosecution Service (

Pedroso 2011).

In a context characterised by the dismantling of labour laws, a process that has been going on with the occasional fluctuation over the past 30 years and basically seeks to make labour protection rules as flexible as possible in the name of greater market efficiency and the promotion of economic growth, workers found themselves more and more in situations of social vulnerability, in a climate of severe austerity, which endured until 2016. In António Casimiro Ferreira’s words (2012), “(…) the dynamics of vulnerability grow stronger when the gap between economic production and social reproduction is facilitated by poor performance on the part of institutions, whose purpose consists precisely in regulating that disconnect. “One of the strategies of the austerity society is to render vulnerable an institution that is crucial for the balance between the economic and the social, to wit, labour law, thus rendering workers vulnerable as well” (

Ferreira 2012, p. 135).

For reasons that do not apply in other legal areas, the sphere of action of Public Prosecutors tends to gain added significance when it comes to ensuring workers’ rights against adverse legislative circumstances, for in such settings they need to rely not only on procedural intervention, but first and foremost on the combined efforts of all the actors involved.

The place of the Public Prosecution Service within the system for accessing law and justice in the area of labour can be better understood through

Figure 1, which illustrates the intermediary role of Public Prosecutors vis-à-vis the whole cast of actors involved in that area. It is important to keep in mind that in the field of labour the actors tend to be of a somewhat peculiar nature on account of the types of dispute with which they have to deal and the very weight of their history. In fact, theirs is a history of a state-arbitrated negotiation process held in the framework of social consultation, which—since the 1974 Revolution in particular—has sought to build consensus between employers and unionised workers. This system is thus more rounded and regulated than those of other legal domains (

Dias 2013a, p. 105) but gradually the state has taken on the role of promoter of imbalances between the various parties. The state does that by means of its legislative choices, which go against a decades-long consensus-building process and thereby make it the main actor in the changes occurring in the regulation of the world of labour (

Ferreira 2005a,

2012).

The role of the Public Prosecution Service is therefore more important than it used to be, because now it has to actively seek solutions which, while following the law, reduce the structural inequalities resulting from the mere implementation of the law and make sure that the rest of workers’ rights are protected, even if the legal framework is becoming increasingly difficult to operationalise in the name of fundamental rights. There are thus multiple points of entry into the system, as can be seen in

Figure 1. These include citizens, trade unions, lawyers (on behalf of either business or workers), business associations, the Authority for Working Conditions, and the Social Security System. Upon being activated by any one of these actors, the Public Prosecution Service is also in a position to direct the workers concerned to any of the entities operating in the field, according to what it considers to be the quickest and fairest solution to the problem at hand. It is also within the power of the Public Prosecution Service to refer the parties—or suggest that they be sent—to the Labour Mediation System, where litigation arising from individual employment contracts (with the exception of matters relating to inalienable rights) can be properly dealt with.

Other actors may be called upon to intervene in ongoing cases in this legal area, according to the needs and type of litigation. That is the case, for instance, with the National Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Science, which determines a worker’s degree of disability resulting from a workplace accident (

Lima 2011). Whether individually or in an organised manner, vulnerable workers can find support in a wide range of actors simply by resorting to one of several entities, among which Public Prosecutors, who can take immediate action by assisting the worker or referring her/him to the appropriate entity. As an example, whenever a worker has a contractual problem with its employer, he/she can request a Public Prosecutor for an initial opinion in order to decide whether he/she can present the issuer at court or it should be better to present it to the Authority for Working Conditions (or to the representative union, if affiliated).

The role of Public Prosecutors in connecting the various actors involved in the labour access system is crucial so that each area can function in a more balanced way and seek decent and timely solutions to whatever needs may emerge, in accordance with the law and respect for the citizenship rights in question. The model presented for the area of labour can be applied to other legal areas of intervention, such as civil, criminal, family and juvenile and/or administrative law

5, once Public Prosecution Services includes, at lower courts, the obligation of the existence of a front-office service open to citizens. Of course, the intervening actors may vary from one domain to another, as do the legal instruments that are made available for citizens to mobilise justice, either individually or collectively, which they often do by going directly to the Public Prosecution Service.

4. Features of the Intermediary Role of Public Prosecutors

The role and space of the Public Prosecution Service within the judicial system can be termed as intermediary, or an interface. In other words, Prosecutors are the element enabling the links between the various parties and entities involved in litigation or in providing citizens, i.e. the interested parties, with the information they need in order to go to whatever entity—whether public or private, judicial or non-judicial—is deemed appropriate to deal with the situation. Professionally, the space and role of Public Prosecutors confer upon them a number of features that are quite unusual and put them in close proximity to citizens, even though their training over the last 40 years has not equipped them for such a job.

In brief, the intermediary or interface role of Public Prosecutors consists in the following:

- -

expediency in intervening in a variety of actions, by “informally” dealing with cases/citizens (before initiating judicial procedures)—front office;

- -

the capacity to provide information and legal counselling, and in certain cases to advise citizens to go to court (and provide them with legal representation);

- -

the ability to act as an “informal” conciliator or mediator, bringing the parties together at the pre-trial stage;

- -

referring citizens to those entities which are better suited to solve their problems and clarify existing doubts, or bringing in other actors whose higher position/responsibility in the system may help find a solution.

This intermediary position, which is characterised by being located within the official system of justice and capable of cooperating and establishing partnerships with other state, private or civil society entities at the pre-trial stage, allows Public Prosecutors to play a leading role in articulating the available formal and informal means of dispute resolution, besides the possibility of taking on any of these roles themselves. Within this multilateral system—to which may still be added the existing conciliation, mediation and arbitration services—and depending on the legal area in question, the Public Prosecution Service acts as an interface between, on the one hand, the citizens who seek its “tutelage,” and on the other, the various institutions “offering” different responses to the multiple needs of citizens.

The Public Prosecution Service is thus a crucial body for ensuring citizens’ access to law and justice. This is because of its intrinsic features (

Dias 2013a), namely the fact that it is:

- -

the only existing “service” with an even geographical distribution throughout the country, which allows it to ensure proximity justice;

- -

the only structure with the capacity to offer a competent, comprehensive (and free) front office counselling service;

- -

the only profession in a position to guarantee independent, credible services in the area of justice;

- -

the only profession to guarantee a simultaneous combination of information, conciliation and mediation services, both formal and informal (followed by legal representation in a number of areas);

- -

the only profession in an intermediary or interface position between justice services and other state and non-state entities.

In short, Public Prosecutors possess a set of skills that have to do with their relative position within the judicial system and their knowledge not only of that system but also of the actors and entities around them. Those skills allow them to take on an interconnecting, intermediary role that goes beyond their traditional legal competences. In addition, such diversity of roles gives the Public Prosecution Service a multifunctional character, which raises a number of doubts and questions and is not entirely consensual. The main point, however, is that, in today’s social, political and judicial context, this is an indispensable magistracy that cannot and should not be curtailed, otherwise there is a risk that the rights of citizens will no longer be effectively upheld (

Dias 2005,

2013a).

5. The Public Prosecution Service as a Professional Project of a Public Nature

The affirmation of the Public Prosecution Service as a professional project of a public nature hinges largely on its ability to build a new action profile whereby the rapport with citizens takes centre stage and judicial and social competences go hand in hand. Just like several other legal professions that of the Public Prosecutor is currently undergoing a transformation (

Dias and Pedroso 2002;

Dias 2013a) whose potential for revalorisation just cannot be ignored by the actors engaged in the political and judicial field.

The three dimensions listed below may help us understand and reflect on the potential for transformation of the Public Prosecution Service. This transformation may take the form of professional legitimisation in its various guises, the acquisition and/or bestowing of judicial and civic competences, and the demarcation of professional boundaries in relation to other judicial operators.

5.1. The Professional Legitimisation of the Intermediary Role

As part of the system for citizens’ access to law and justice, the front office component of the Public Prosecution Service has long been somewhat undervalued not only by the state, but also by magistrates and lawyers. This becomes obvious if we analyse the role, evolution and statistical data of the Offices for Legal Advice, which operate under the responsibility of the Portuguese Bar Association, the Portuguese state, and local authorities

6. We can also see that the various dispute resolution mechanisms in place tend to apply to ongoing situations rather than to prevention and information. Other public services, on the other hand, have performed better in this respect. That is the case, for instance, with the Authority for Working Conditions (

IGT 2007;

ACT 2015), which has improved citizens’ access to labour information (which also qualifies as legal information) and the Commissions for Protection of Children and Young People at Risk (

CNPCJR 2006,

2015), which allow for a degree of informality in pursuing cases that would otherwise find it hard to make it to the system by way of the courts (

Ferreira et al. 2007;

Pedroso 2015). As to the “Citizen’s Shops”—together with their virtual counterpart, the Citizen's Portal—they have made it easier not only to ensure the effectiveness of citizens’ rights and citizens’ access, in an integrated fashion, to the services provided by the various public entities, but also to promote and enable access to legal and other types of information in a number of areas.

7Just like other highly trained professionals, the members of the legal professions have long sought to legitimise their work by increasing the levels of specialisation and technicity (

Dias and Pedroso 2002;

Dias 2013a). However, in these times of professional identity crises, when professional functions and competences are being redesigned and there is a growing awareness of citizenship rights, the legal professions are seeking professional revalorisation through direct contact with the citizens, who are truly their

raison d’être. Strangely enough, however, that has not been, to its full extent, the path taken by magistrates (i.e., judges and prosecutors) in Portugal.

Notwithstanding their status as privileged actors—by virtue of being in contact with the common citizen in the context of the courts—Public Prosecutors have committed three major errors. Because of those errors, the professional valorisation of such close interaction with citizens is being hindered, even as Prosecutors engage in a strategic effort to (re)valorise their function and (re)build their own professional identity:

- 1

Internally, it is the prosecutors themselves (through their hierarchical structures) who do not stress enough or question this side of their day-to-day performance, which also fails to be mentioned in detail and with as much weight as the rest of the information in their reports, nor is it adequately valued in the context of their professional performance assessment (

Dias 2004);

8- 2

Externally, the error resides in the fact that this counselling service is not viewed as dignified enough by Prosecutors. Hence its inconspicuous presence in protest/political and professional legitimisation discourse (as voiced by the Public Prosecutors’ Union) and in the public strategy of the Prosecutor-General’s Office;

9- 3

At the interprofessional level, the front office has not been duly embraced, valued and recognised amid the other legal professions—nor, for that matter, by the other legal professions—as the one specificity that can ensure citizens’ access to law and justice, besides contributing significantly to the definition of professional identity as something based on social, political and judicial legitimisation with regard to citizens.

These triple strategic actions on the part of these professionals causes confusion and diversion with regard to how the services provided by Public Prosecutors are viewed and integrated. And yet this particular service does exist, and all the more so after the implementation, as recently as September 2014, of the Judicial Reform Map, which determined that an adequately organised, well publicised counselling service be established in every District Court (

Dias 2016). But it is not properly assessed, nor is it given much weight within the Public Prosecution Service’s overall activity. In other words, it is not sufficiently valued, with the same importance of the other criteria used in the evaluation processes of Public Prosecutors. In light of the regulations and performance assessment guidelines in place, counselling-related activities are somewhat demeaningly termed “front office,” with no regard for potential gains. Thus, a Public Prosecutor who shows an “aptitude” for performing this type of service may end up being penalised for failing to process as many cases as expected (with the total number of cases remaining the primary criterion for statistical and professional performance evaluation purposes). Since 2005, which was when global data on the counselling services first began to be taken into account, the Activity Reports of the Prosecution-General’s Office

10 clearly indicate that this particular activity has been given short shrift in the context of the total amount of work carried out by Public Prosecutors. Furthermore, the data itself raises a number of questions concerning collection methods, national representativeness, or who the service provider actually was, not to mention the practical results achieved by the service among the citizens who resorted to it. The Public Prosecutors’ Union has contributed significantly to this situation, mainly by omission. Things have improved over the last few years, during which the issue has been treated by the Union as important for professional (re)valorisation, although never as one of its strategy’s main banners. As shown above, the internal devaluing of this part of the work done by Public Prosecutors inevitably impacts on professional strategy at the external and interprofessional level.

The Public Prosecution Service’s professional strategy as externally pursued by its governing bodies or by the Public Prosecutors’ Union—especially as far as citizens are concerned, for they can be crucially affected—is not very different from its internal strategy. By the same token, there is no communication strategy aimed at people at large, either at the local or at the national level, with a view to publicise the very existence of the front office and its multiple possibilities. Thus, the external devaluing of the intermediary role leads to a disregard for those elements that are basic in the effort towards social and political legitimacy. As a consequence, a major opportunity is missed to bring external allies into the balance of “forces” that make up the configuration of professional competences of the various legal professions and even to redistribute those forces within the judiciary.

The professional devaluing, both internal and external, of the intermediary role played by the Public Prosecution Service’s front office has an immediate logical consequence: the failure to affirm that role at the interprofessional level and to claim its specificity vis-à-vis the other legal professions. That specificity, marked by a close proximity to the common citizen, could serve as the basis for a whole reconfiguration of the professional identity of Public Prosecutors, whose professional strategy in the last decades has instead cultivated proximity to the figure of the judge, according to a principle of similarity that has turned into a veritable game of mirrors. This strategic error is conducive to political weakness when negotiating with other judicial and political actors, pushing the profession into an exceedingly confined field of action—a space dominated by the judicial element and by the figure of the judge, thereby relegating the Public Prosecutor to a secondary role. And while other professional competences are equally vital for him or her to do a good job, the half-hearted fulfilling of this multifaceted, hybrid, connecting place/space results in the lack of a (re)valorisation strategy at the professional level and, at the functional level, in peoples’ diminished ability to exercise their citizenship rights.

The valorisation of the intermediary role of Public Prosecutors has been gradually increasing, particularly in the areas of social intervention, but still without becoming a central concern or a real priority. In fact, such steps as the inclusion of this item in the agenda of the last three conferences of the Public Prosecutors Union or the constant references to it in the documents relating to the proposals for reviewing the Inspection Regulation and the Statute of the Public Prosecution Service were never consistent enough to take centre stage in the profession. The inaction of the Prosecutor-General’s Office over the last decade in this particular respect, under no pressure from the Public Prosecutors Union, has also contributed to the highly stagnant relationship between the profession and citizens in general. On the other hand, other professions, and judges in particular, have been politically and judicially active and proved to possess negotiation skills to pursue their professional goals

11/

12. The Judicial Map Reform was a clear example of this (

Dias 2016;

Gomes 2013). It is nevertheless true that the amendments to the judicial map, introduced by the Minister of Justice of the 19th Constitutional Government, Paula Teixeira da Cruz, never completed the reform of the laws that define Portugal’s judicial architecture, namely the Statute of Judicial Court Judges and the Statute of the Public Prosecution Service. As recently as 2016 this situation still created a major disconnect between the new reality of Portuguese courts and the way the magistracies are organised. This, in turn, meant that the solution to a number of problems, such as the organisation of the Public Prosecution Service, had to be postponed.

5.2. Building Civic-Professional Competences

The current training of Public Prosecutors is probably not as comprehensive and adequate as would be expected for an intermediary role, as that role often requires analytical and evaluative skills to deal with personal predicaments that do not involve or constitute a legal offence, even if some degree of curtailment of a citizen’s rights could be at stake. In fact, the very diversity and social complexity of the issues with which Public Prosecutors may be called upon to deal raise the question of the quality of the service provided. But the legal content aspect itself should not be overlooked, since the information and counselling provided at the front office may require a kind of training that is different from what is currently provided at the Centre for Judicial Studies. For the fact remains that these are very different from the functions Prosecutors have been “trained” for, namely as regards the civic component of the job. To put it differently, knowledge of the law and of the proper legal procedures is not enough, as it is also necessary to know how to listen, comprehend and intervene in an appropriate manner.

The question of the requirement for compulsory supplementary training upon entering the Centre for Judicial Studies or when a Public Prosecutor has to serve in a specialised court should be on the table, not only in terms of legal knowledge per se, but also in terms of the procedures relating to front office counselling and (in)formal dispute resolution at an early, pre-trial stage.

Nowadays the exercise of an intermediary role, especially in the case of face-to-face interaction with citizens, calls for demanding professional procedures that can be acquired through further training, since not everybody will spontaneously develop those skills and competences over time. In cases where Prosecutors serving in courts with a low level of interaction with the public get transferred to courts where they are required to engage directly with citizens on a regular basis, it is imperative that they receive adequate training to be able to deal with this new reality of proximity and close interaction. For their part, citizens should not have to wait for the Public Prosecutor to acquire the necessary on-the-job experience or develop an aptitude for front office work, because in the meantime their interests will be at risk of being greatly disserved.

Paulo Morgado de Carvalho

13 argues that the work performed on behalf of citizens should not be dependent on a Prosecutor’s individual “profile” and that Public Prosecutors should possess proper training, professional awareness and the necessary tools for ensuring quality counselling, as is the case with their other functions. Although Carvalho does not specifically mention the intermediary role, his experience as Inspector-General for Labour leads him to argue in favour of the profession’s acquiring new skills to fulfil that task.

Thus, the training offered at the Centre for Judicial Studies should be overhauled, by rethinking the advantages and disadvantages of providing a training separate from that of judges from very early on. After a brief phase of joint training, based on which trainees may consciously decide what kind of magistrates they want to become, the next phase of the training should take one of two separate paths, depending on which functions they will eventually perform in the courts. In the case of Public Prosecutors, in addition to research and coordination/institutional articulation skills, special attention should be paid to the ability to deal with people in a variety of circumstances.

The potential complexity of many of the occurrences that are bound to arise in the front office service is probably greater than that of judicial processes or investigations, for they cover situations that fall outside the legislation and procedures in place and do not leave time for analysis and consolidation in the search for the right solutions. The response time is not the same to which magistrates are used in the realm of justice. It is characterised by immediacy, and Public Prosecutors will be all the more successful if they prove able to meet citizens’ aspirations at once and in an integrated, analytically adequate fashion. In short, this is not a simple job, but a difficult and complex one, requiring adequate professional training that should not only be part of basic and continuous training but also be made mandatory.

5.3. (Re)defining the Interprofessional Boundaries of the Intermediary Role

The legitimacy of providing legal information and counselling continued to be questioned in recent years, although not as strongly as had been the case at the beginning of the century. The debate has been over whether these functions do not overstep the competences of the Public Prosecution Service, which may thus be usurping the competences of other legal professions, and of lawyers in particular (

Ferreira et al. 2007). The legitimacy issue has to do, before anything else, with the existing “competition” as far as competences are concerned and with the abundance of professionals in such a small market

14.

The reason that the independence and impartiality of Public Prosecutors as providers of legal information and counselling are viewed as questionable has to do with the fact that the Public Prosecution Service may end up being one of the parties involved in subsequent procedural stages. Thus, the opinions issued by a Public Prosecutor may lack impartiality and objectivity because they are legally “formatted” to begin with, i.e. they tend to follow principles and criteria that place legal duty above other considerations. Legal imperatives don’t always override personal dilemmas, and in fact the imparting of information and counselling does not necessarily have to follow what is established by law, although there is not enough information available to validate this argument.

Together with the issue of legal representation, the whole question of legal information and counselling being provided to citizens by Public Prosecutors is one of the most controversial topics among the various judicial operators. Here are some of the arguments from both sides of the debate:

Against. These are the arguments put forward against maintaining a front office service in which Public Prosecutors provide legal information and/or counselling: (a) the Public Prosecution Service’s lack of human resources; (b) the need for Public Prosecutors to refocus on their magistrate, strictly judicial functions; (c) the inequality obtaining between a Public Prosecutor and a lawyer when representing workers, for instance, given that in this case the magistrate takes on a dual role—of lawyer and judicial authority—thereby symbolically influencing the litigants; (d) and the existence of other entities in a position to provide legal information and to which citizens can/should be immediately referred.

In favour. The arguments for maintaining the current model are basically the following: (a) the potential for dispute prevention and conciliation inherent in the Public Prosecution Service’s sphere of action; (b) the lack of credible alternatives to which economically disadvantaged citizens may turn when they cannot find support from entities that might be better prepared to provide it (as is the case with non-unionised workers); (c) the perception, by citizens in general, that the front office is doing a good job; (d) the need to maintain the Public Prosecution Service in the courts, there to pursue all its other functions, alongside and in conjunction with the front office counselling service; (e) and the intermediary role played by Public Prosecutors within the fragile framework of the system for accessing law and justice.

All these arguments notwithstanding, the lack of coherent and effective alternatives has kept controversy to a minimum, even among those professions that might profit the most from a redesign/reduction of the Public Prosecution Service’s competences, particularly in the social areas

15. In the family and juvenile area, for example, where the situations involved can be problematic, especially in the case of minors at risk, the competences of Public Prosecutors tend not to be openly challenged, even if lawyers happen to be convinced that the only reason Prosecutors represent those minors is the compensation they get from the state (

Ferreira et al. 2007). What is more, even those structures that have been established or strengthened over recent years—such as the Peace Judgeships, the arbitration and mediation systems or the Offices for Legal Advice—seem as yet unable to take on the role played by Public Prosecutors. What such structures seem capable of doing, judging by their current performance, is partially supplement the work carried out by the Public Prosecution Service, thus providing citizens with more means for resolving disputes, even though the availability of those means continues to be largely ignored.

The assumption by the Public Prosecution Service of a more proactive role does not necessarily imply a “usurpation” of competences, which, at present, belong mostly to lawyers. Nor does it mean that lawyers cannot or should not assume some of the Public Prosecutors’ competences, nor that the current vagueness cannot be clarified. What these reflections wish to stress is that, in view of the current performance of the Public Prosecution Service and the conditions obtaining in the system for accessing law and justice (made worse by Portugal’s recent financial crisis), Public Prosecutors have ample room for affirmation by way of a more active professional stance, placed at the service of the promotion of legality and the rights of citizens. No strict demarcation of boundaries will be necessary as long as the various professions clearly know what the role of each one of them is supposed to be. Provided, of course, that proper guarantees are given, first, of the interests of citizens and the interest of the state—both with regard to its responsibilities in implementing an integrated, complementary policy for accessing law and justice, and with regard to the need to provide the judicial system with financial sustainability—and second, of the autonomous exercise of their respective competences by each of the two professions.

In the coming years, the demarcation of interprofessional boundaries promises to be a rather more controversial topic than it has ever been. The main reason for this is the need to clearly define the scope of action of each legal profession in relation to other legal areas, as part of the effort to draw the boundaries of the comprehensive counselling work of Public Prosecutors exercising their intermediary role. Nevertheless, formal recognition that among the profession’s competences should be included the legality of the various types of activity carried out as part of the front office service is still not under discussion, despite its being a vital element for the exercise of citizenship in the present circumstances.

6. Conditions for a Proactive Public Prosecution Service

The above analysis shows that the professional functions and practices of the Public Prosecution Service have a potential for activism that is still largely unexplored

16. In other words, a Public Prosecutor is an actor who seeks to ensure compliance with the law while making sure that citizens’ rights are protected. But even this institutional framework does not preclude a potential for change in the actions of Public Prosecutors, which they can perform either in a passive or active, reactive or proactive manner. Historically this issue has certainly been the cause of much political, scientific and/or legal debate in various countries, not least Portugal.

Even under their current statute, Public Prosecutors have now all the necessary legal and functional conditions for carrying out their duties in a proactive manner. What needs to be done is not so much to cover new competences, as to make sure that the existing model is fully explored. This, of course, will depend largely on a multiple set of conditions without which the Public Prosecution Service will find itself unable to realise the full potential of the functions it is in a position—and is supposed—to perform.

This is not to say that the Public Prosecution Service should present itself as a model of judicial activism, because it is the judges, not the Prosecutors, who give the final court decisions. But Public Prosecutors can take a proactive stance in promoting the kind of actions that make it possible, on the one hand, to easily and quickly meet the aspirations and needs of citizens, thus advancing a new paradigm of proximity, and on the other, to use greater diligence and power of initiative in investigating the potential problems that afflict society, undermine the rule of law, and/or go against the public interest.

17Commenting on a new programme of action to fight corruption that features the Public Prosecution Service in a leading role, Euclides Dâmaso Simões defines its activism in terms of four major dimensions: organisation, prevention, repression and training. Given the broad scope of competences and responsibilities of Portugal’s Public Prosecutors, the proposal can be applied across all areas of intervention of the Public Prosecution Service, thus covering all social practices. Fully aware of the increasingly complex ways in which society works in all its different areas, the Public Prosecution Service must plan effectively for these four dimensions of action and thereby help shape a proactive judiciary as envisaged by Antoine

Garapon (

1998), instead of assuming a purely reactive stance.

Because of the growing importance of diffuse and collective interests, which have added a whole new range of areas relating to administrative law—such as public health, the environment, spatial and urban planning, quality of life, consumption, and cultural heritage, among others—to the more traditional domains of crime, labour, family/juvenile, and civil law, the Prosecutor-General's Office created its own Collective and Diffuse Interests Unit, established under a Decision of 20 January 2014 to provide support for the Prosecutor-General’s activities (

Procuradoria Geral da República 2014).

This is how the Decision justifies the creation of the Unit:

Given that the activities of the Public Prosecution Service are in the public interest and will be conducted mostly in administrative courts, its functional performance needs to be improved, deepened, boosted and encouraged.

The complexity of the matters involved calls for ready access to resources—namely an adequate degree of expertise—to be divulged and made available as and when necessary.

It also calls for expert knowledge and for close coordination with areas that are inseparable from the administrative jurisdiction—such as civil and criminal, as well as the Court of Auditors—as part of an integrated approach to all phenomena susceptible of being brought under the various jurisdictions.

In addition, the Public Prosecution Service’s capacity for response and improvement entails coordinated action at national and local level, objective setting, uniform procedures and better communication, while highlighting the accumulated case law.

The main functions announced in this context aim to make Public Prosecutors more proactive and to seek, identify and promote good practices, institutional networking, organisational improvements and communication channels, among other goals, with a view to ensuring better job performance and therefore improving quality of life and widespread effectiveness of citizens’ rights on a collective scale. It is a small and mostly symbolic step, which nevertheless shows a transformation in the way Public Prosecutors operate, under the leadership of Prosecutor-General Joana Marques Vidal.

Writing about the performance of Brazil’s Public Prosecution Service in the field of health, Felipe

Asensi (

2010) states that it “has the institutional capacity to create space for dialogue, for it enables communication among the main actors involved in the process of formulating, managing and overseeing public health policies. Thus, the main strategy followed by the Public Prosecution Service has taken the form of extrajudicial action, which not only expands the capacity to act but also helps give effect to the right to health. This translates into a juridification of disputes (disputes are discussed from the legal standpoint), but not necessarily into judicialisation (as much as possible, disputes are not pursued to court). As a result, the Public Prosecution Service is valued as an institution that makes it possible to expand dialogue in order to effectively process and resolve disputes” (Introduction).

In light of the present analysis, this description allows us to easily transpose to the Portuguese situation all the potential for action, intervention and transformation inherent in the Public Prosecution Service by virtue of its competences, functions, judicial and professional practices and, most of all, its public responsibility towards society. It is imperative that it adopt a more proactive stance in enforcing the law and that it be allowed the initiative to take actions in defence of the public interest, whether at the individual or collective level. At this point let us then resume Dâmaso Simões’s four dimensions, to illustrate those mechanisms that can help Public Prosecutors perform their competences in a proactive manner (

Simões 2015):

- -

Training: a strengthening, in initial training, of such components as autonomy, power of initiative, and articulation and coordination strategies, with the ultimate aim of giving effect to the intermediary role and thus build a Public Prosecution Service that is capable of carrying out its competencies; continuous training programmes designed for this new paradigm of professional performance, to include judicial and non-judicial, state and non-state actors; incentives to and participation in further training and discussion sessions with other actors, both judicial and non-judicial, who may be relevant in terms of the collaboration and articulation of the various fields of intervention.

- -

Organisation: improvements to the Public Prosecution Service’s internal organisation, and networking with the rest of the judicial actors operating inside the courts; improvements to existing channels of communication and to cooperation with state and non-state entities, and organised civil society in particular; improvements to the mechanisms in place for front office counselling, with a view to making interaction easier, faster and more effective; definition, emanating from the Prosecutor-General’s Office, of the mechanisms and coordinators of the various services and areas of intervention, to ensure effective articulation between the verticality of the organisational structure and the horizontality of procedures.

- -

Prevention: participation in creating and disseminating prevention activities, in conjunction with the (state and non-state) leading actors involved, including the need to provide citizens with further information about the existence, competences, functioning and way of accessing the Public Prosecution Service as an entity devoted to helping, supporting and guiding citizens with problems to solve.

- -

Repression: enforcement of the law by the Public Prosecution Service, not just by reacting to the cases that go to court but also by proactively scanning the news and reading the signs or whatever meets the eye (as is the case with environmental pollution), so as to promote the individual and collective good of citizens across all areas of activity.

In this context, mention should be made of the

Justiça + Próxima (“Closer Justice”) Programme,

18 which seeks to reinforce the “official” nature of the Public Prosecution Service’s responsibility in its interaction with citizens, especially as regards front office, face-to-face, and electronic services. The programme in question thus provides for the establishment of an electronic site linking citizens to the Public Prosecution Service, with the Ministry of Justice offering the following rationale:

In a joint effort with the Prosecutor-General’s Office, an integrated, multi-channel front office is to be established within the Public Prosecution Service, with the aim of increasing simplicity and citizens’ access to justice, namely by means of:

□ an “Online Public Prosecution front office” to provide information and set face-to-face appointments, among other functionalities;

□ an online “Citizen’s Space” where citizens can put questions to the Public Prosecution Service, in addition to the face-to-face counselling given at the Public Prosecution branches located in the courts.

The conditions—at the political (Ministry of Justice), institutional (Prosecutor-General’s Office) and professional level (Public Prosecutors’ Union)—are thus met for the emergence, in a more consistent and open fashion, of a Public Prosecution Service at once (re)invented and desirous of becoming a different kind of protagonist, more focused on the demands with which its performance and image are now faced. It remains to be seen whether the next few years will prove (or disprove) this trend.

7. Concluding Remarks

The purpose of these reflections, based on previous writings by the present author and other relevant sources, is to answer a question that is both simple and difficult: can Public Prosecutors build their profession around the citizen and do it in a proactive manner? This does not mean that the work carried out by the Public Prosecution Service at present is not devoted to upholding citizens’ rights and making sure that legality and compliance with the law are enforced. What it does mean is that a shift in the current paradigm of the role and place of Public Prosecutors is being proposed, so they can take a fresh stance—accompanied by the necessary changes in terms of the professional practices and organisational model of the courts—and perform their functions in greater proximity to citizens. It also means that Portugal’s current model for accessing law and justice should take as its point of reference the Public Prosecution Service and its intermediary role as described above.

Given the absence of a broad, effective and integrated model for accessing law and justice, by means of which all the relevant information as well as any problem-solving mechanisms can be rapidly made available to citizens, the Public Prosecution Service tends to take a central role in ensuring the rights of citizens. The poor performance of alternative dispute resolution mechanisms, combined with the difficulties and intricacy in accessing the many institutions capable of providing support to citizens and solving their problems, puts the Public Prosecution Service in a privileged, central, hub-like position for dealing with the public, notably via that veritable space of citizenship, the front office counselling service.

Against this background, it is all of the more pressing that Public Prosecutors base their activity on a broad interpretation of their competences, which should receive institutional backing and increasing professional recognition, so as to make it easier to work with other providers of information and legal counselling across the various areas of intervention. This stance, combined with the duty to operate in a network for the benefit of citizens, adds complexity to the profession while endowing it with increased relevance and responsibility, thus contributing greatly to (inter)professional revalorisation.

It is a known fact that the “productivity” of Public Prosecutors has improved significantly in recent years, despite the overall increase in the backlog of cases (

Dias 2013a, p. 181). But it should also be pointed out that their performance potential has not been fully realised yet. For that to happen, a number of changes will have to take place in the organisational model of the Public Prosecution Service, namely to allow citizens to have many of their problems either promptly resolved or adequately referred or clarified at an early stage. Studies on the benefits of a different type of approach still need to be done, and this could be a reality should the Prosecutor-General's Office make it a priority.

The role of Public Prosecutors in connecting the various actors involved in the system for accessing law and justice across the different areas of intervention is, therefore, crucial so that each area can function in a more balanced way and seek decent solutions and timely responses to whatever needs may emerge, in accordance with the law and respect for the citizenship rights in question. Thanks to their skills, which have to do with their relative position within the judicial system and their knowledge not only of that system but also of the actors and entities around them, Public Prosecutors are capable of assuming a multifunctional, interconnecting and intermediary role that goes beyond their traditional legal competences. Theirs is an indispensable magistracy in today’s social, political and judicial context that cannot and should not be curtailed, otherwise there is a risk that the rights of citizens will no longer be effectively upheld.

To paraphrase Boaventura de Sousa Santos on his proposal of a sociology of absences and a sociology of emergences, the Public Prosecution Service can be dared to assess that which does not get to go to court, just as we need to investigate and anticipate emerging disputes, either to preempt them or to prevent them from doing further social damage (

Santos 2002c). This approach may include specific actions by magistrates and has to be based on high levels of training and awareness, as part of a whole new paradigm of action and functioning. In short, the move towards a new proactive stance by the Public Prosecution Service will depend largely on its leadership proving capable of providing it with the necessary drive, awareness and training, as well as the required changes in terms of organisation and professional practices, to achieve that which still leaves many magistrates terrified:

a Public Prosecution Service for the people.