Children of Imprisoned Parents and Their Coping Strategies: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Coping Theories

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Design

3.2. Search Strategies and Sources

3.3. Inclusion Criteria

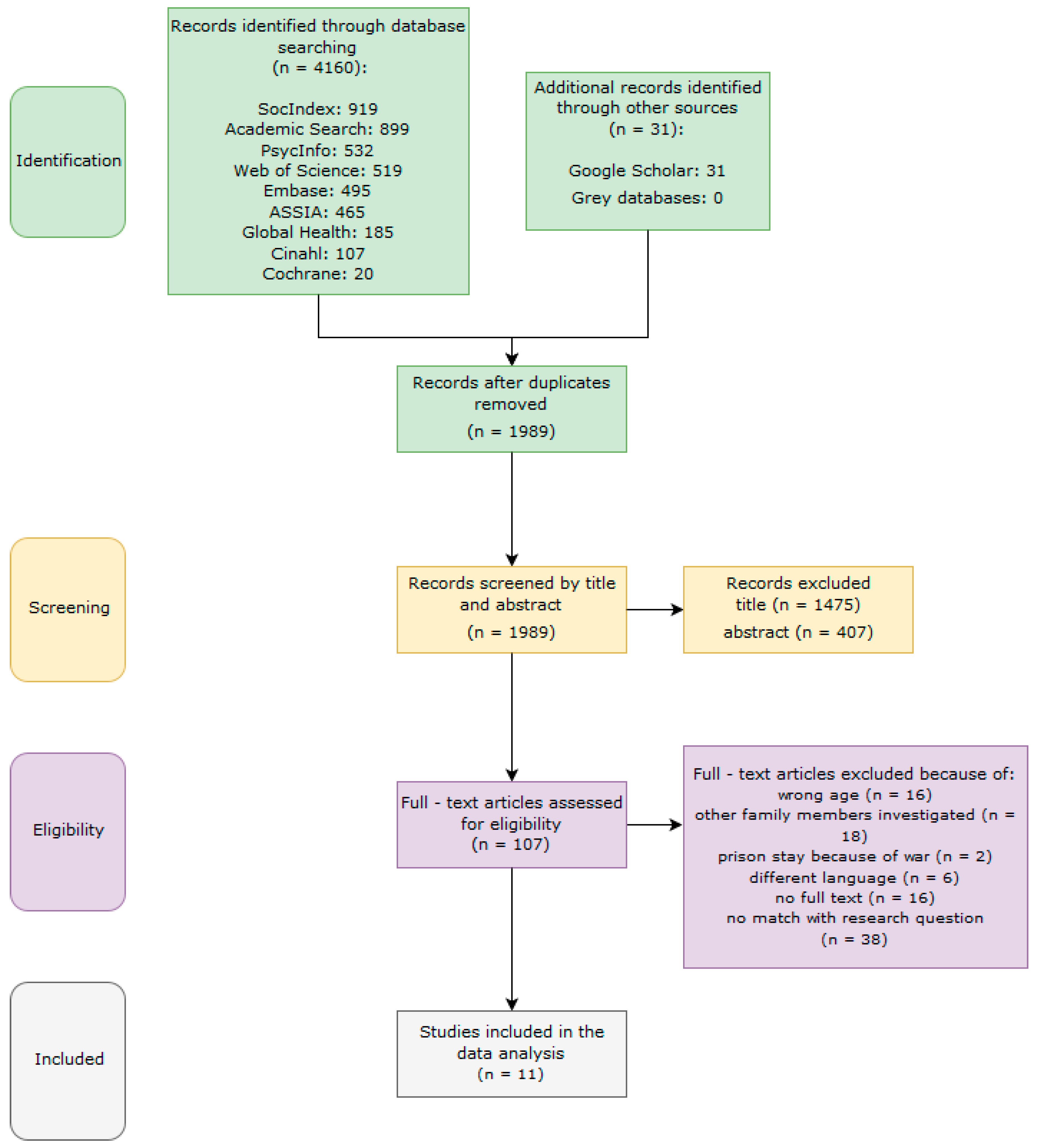

3.4. Search Outcomes

3.5. Quality Assessment

3.6. Data Extraction and Synthesis

4. Results

4.1. Coping Strategies

4.2. Interventions

5. Discussion

5.1. Coping

5.2. Interventions

5.3. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Penal Reform International. Children of Incarcerated Parents. Available online: http://www.penalreform.org/priorities/justice-for-children/what-were-doing/children-incarcerated-parents/ (accessed on 19 December 2016).

- The Annie E. Casey Foundation. A Shared Sentence: The Devastating Toll of Parental Incarceration on Kids, Families and Communities. Policy Report. 2016. Available online: http://aecf.org/m/resourcedoc/aecf-asharedsentence-2016.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2016).

- Jones, A.D.; Gallagher, B.; Manby, M.; Robertson, O.; Schützwohl, M.; Berman, A.H.; Hirschfield, A.; Ayre, L.; Urban, M.; Sharrah, K. COPING Final, Children of Prisoners. Interventions and Mitigations to Strengthen Mental Health, 2013. Available online: http://childrenofprisoners.eu/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/COPINGFinal.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2016).

- Oldrup, H.; Frederiksen, S.; Henze-Pedersen, S.; Olsen, R.F. Indsat Far- Udsat Barn? Hverdagsliv og Trivsel Blandt Børn af Fængslede. Det Nationale Forskningscenter for Velfærd, 2016. Available online: https://pure.sfi.dk/ws/files/473564/1617_Indsat_far_udsat_barn.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2016).

- Murray, J.; Farrington, D.P.; Sekol, I. Children’s antisocial behavior, mental health, drug use, and educational performance after parental incarceration: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2012, 138, 175–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, R.D.; Fang, X.; Luo, F. The impact of parental incarceration on the physical and mental health of young adults. Pediatrics 2013, 131, e1188–e1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Masi, M.E.; Teuten Bohn, C.; Benson, D.B. Children with Incarcerated Parents. A Journey of Children, Caregivers and Parents in New York State; Council on Children and Families: Rensselaer, NY, USA, 2010.

- Jakobsen, J.; Scharff Smith, P. Børn af Fængslede-en Informations- og Undervisningsbog, 1st ed.; Narayana Press: Gylling, Danmark, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shlafer, R.J.; Gerrity, E.; Ruhland, E.; Wheeler, M. Considering children’s outcomes in the context of complex family experiences. Child. Mental Health Rev. 2013, 1–17. Available online: http://www.extension.umn.edu/family/cyfc/our-programs/ereview/docs/June2013ereview.pdf (accessed on 23. May 2017).

- Karlsson, R. Vad Sager Forskningen om Barn Till Fängslade Föräldrar. En Forskningsöversikt; RiksBryggan: Karlstad, Sweden, 2007; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, A.; Flynn, C. Supporting imprisoned mothers and their children: A call for evidence. Probat. J. 2013, 60, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, H. The strains of maternal imprisonment: Importation and deprivation stressors for women and children. J. Crim. Justice 2012, 40, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boswell, G.; Wedge, P.; Kingsley, J. Imprisoned Fathers and Their Children; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Parke, R.D.; Clarke-Stewart, C.A. From Prison to Home: The Effect of Incarceration and Reentry on Children, Families, and Communities. Available online: https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/effects-parental-incarceration-young-children (accessed on 25 April 2017).

- Murray, J.; Farrington, D.P. Parental imprisonment: Effects on boys’ antisocial behaviour and delinquency through the life-course. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2005, 46, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinner, E.A.; Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J. The Development of Coping. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 119–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ICF International. Mentoring Children Affected by Incarceration: An Evaluation of the Amachi Texas Program. Available online: http://docplayer.net/6592271-Mentoring-children-affected-by-incarceration-an-evaluation-of-the-amachi-texas-program.html (accessed on 14 December 2016).

- Children of Promise, NYC. Our Programs. Available online: http://www.cpnyc.org/about-us/ (accessed on 14 December 2016).

- Murray, J.; Farrington, D.P. Evidence-based programs for children of prisoners. Criminol. Public Policy 2006, 5, 721–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compas, B.E.; Connor-Smith, J.K.; Saltzman, H.; Thomsen, A.H.; Wadsworth, M.E. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: problems, progress, and potential. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 87–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonovsky, A. Unraveling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay Well, 1st ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky, A. Health, Stress and Coping. New Perspectives on Mental and Physical Well-Being, 1st ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, T.K.; Johnsen, T.J. Sundhedsfremme i Teori og Praksis, 2nd ed.; Forlaget Philosophia: Aarhus, Danmark, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, M. The Handbook of Salutogenesis. In The Sense of Coherence in the Salutogenic Model of Health; Mittelmark, M.B., Sagy, S., Eriksson, M., Bauer, G.F., Pelikan, J.M., Lindström, B., Espnes, G.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mittelmark, M.B.; Sagy, S.; Eriksson, M.; Bauer, G.F.; Pelikan, J.M.; Lindström, B.; Espnes, G.A. The Handbook of Salutogenesis; Springer Open: Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 10, ISSN 978-3-319-04600-6. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Heyvaert, M.; Hannes, K.; Maes, B.; Onghena, P. Critical appraisal of mixed methods studies. J. Mixed Methods Res. 2013, 7, 302–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijkers, M. What is a scoping review? KT Update 2015, 4, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Dictionaries. Child. Available online: http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/child (accessed on 19 December 2016).

- Pluye, P.; Robert, E.; Cargo, M.; Bartlett, G.; O’Cathain, A.; Griffiths, F.; Boardman, F.; Gagnon, M.P.; Rousseau, M.C. Proposal: A Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool for Systematic Mixed Studies Reviews, 2011. Available online: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/84371689/MMAT%202011%20criteria%20and%20tutorial%202011-06-29updated2014.08.21.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2016).

- Pluye, P.; Hong, Q.N. Combining the power of stories and the power of numbers: Mixed methods research and mixed studies reviews. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NICE. Appendix B. Available online: http://www.nice.org.uk/article/pmg6b/chapter/appendix%20b:%20methodology%20checklist:%20systematic%20reviews%20and%20meta-analyses (accessed on 14 December 2016).

- Miller, K.M. The impact of parental incarceration on children: An emerging need for effective interventions. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2006, 23, 472–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruster, B.E.; Foreman, K. Mentoring children of prisoners: Program evaluation. Soc. Work Public Health 2012, 27, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raikes, B. The role of schools in assisting children and young people with a parent in prison—Findings from the COPING project. In Identities and Citizenship Education: Controversy, Crisis and Challenges. Selected Papers from the Fifteenth Conference of the Children’s Identity and Citizenship in Europe Academic Network; CiCe: London, UK, 2013; pp. 77–384. [Google Scholar]

- Laakso, J.; Nygaard, J. Children of incarcerated parents: How a mentoring program can make a difference. Soc. Work Public Health 2012, 27, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manby, M.; Jones, A.D.; Foca, L.; Bieganski, J.; Starke, S. Children of prisoners: Exploring the impact of families’ reappraisal of the role and status of the imprisoned parent on children’s coping strategies. Eur. J. Soc. Work 2015, 18, 228–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, A.; Steinhoff, R. Children’s experiences of having a parent in prison: “We look at the moon and then we feel close to each other”. Analele Ştiinţifice ale Universităţii» Alexandru Ioan Cuza «din Iaşi. Sociologie şi Asistenţă Socială 2012, 5, 77–96. [Google Scholar]

- Bocknek, E.L.; Sanderson, J.; Britner, P.A. Ambiguous loss and posttraumatic stress in school-age children of prisoners. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2009, 18, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, D.W.; Lynch, C.; Rubin, A. Effects of a solution-focused mutual aid group for hispanic children of incarcerated parents. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2000, 17, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesmith, A.; Ruhland, E. Children of incarcerated parents: Challenges and resiliency, in their own words. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2008, 30, 1119–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, C.; Bhat, C.S. Supporting students with incarcerated parents in schools: A group intervention. J. Spec. Group Work 2007, 32, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.I.; Easterling, B.A. Coping with confinement: Adolescents’ experiences with parental incarceration. J. Adolesc. Res. 2015, 30, 244–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, M.; Shlonsky, A. Systematic Synthesis of Qualitative Research; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchenham, B.; Charters, S. Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering. 2007. Available online: https://www.elsevier.com/__data/promis_misc/525444systematicreviewsguide.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2016).

- Antonovsky, A. Helbredets Mysterium- at Tåle Stress og Forblive Rask, 1st ed.; Hans Reitzels Forlag: København, Danmark, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Tisdall, E.K.M.; Kay, H.; Cree, V.E.; Wallace, J. Children in need? Listening to children whose parent or carer is HIV positive. Br. J. Soc. Work 2004, 34, 1097–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thastum, M.; Johansen, M.B.; Gubba, L.; Olesen, L.B.; Romer, G. Coping, social relations, and communication: A qualitative exploratory study of children of parents with cancer. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2008, 13, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference of the Reviewed Study | Location | Study Population (n) | Age or Grade in School | Method | Aims | Eligibility | Ethnicity | Coping Strategies | Key Conclusions | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [42] | US | 34 children | 8–17 | Descriptive qualitative open-ended interviews. The interview topics included the demographic characteristics of the child, caregiver, and the imprisoned parent, information about the incarceration of the parent, social, - family, - school-, and personal experiences and coping strategies | To describe the effect of parental imprisonment on children from children’s perspectives | Children’s ages ranged from 8 to 17 at the beginning of the study, parent in prison, both child and caregiver willing to participate, several recruitment methods to increase broader participation | 62% African American 19% native American 19% white | Supportive people were helpful for coping, involvement in activities and sports, theatre and church/faith (distraction activities), the need for a place to feel normal, overall resourceful and creative coping strategies, children had responsibilities that made it easier to challenge hard situations and cope | Supporting children through support from families and caregivers, good communication. There were feelings of isolation and stigma, but a need for support groups, friends and mentors. The majority of participants did well in school. Most children were mature and developed for their age, but need support groups, mentors and places to feel normal | No randomization. Most children <13 years old, and most experienced paternal incarceration |

| [38] | UK | 6 children and their parents | 7–17 | Used qualitative interviews from 161 children and more in-depth interviews with six cases, cross-country comparisons. Themes: resilience, attachment and loss as well as gender significance, stigma and support | To assess children’s coping mechanisms and investigate the relationship between parent’s perceptions and behaviours related to the prison stay | Having a parent in prison; only six cases were interviewed from the larger cohorts | Children from Sweden, UK, Germany and Romania; other information was not provided | Openness and honesty influence children, school and peers are important distractions and activities, sports and therapeutic groups were seen as helpful, it was important for the children to talk about their parent’s situation, family policies about disclosing and managing stigma | Coping strategies were influenced by the children’s surroundings and how/if it was talked about in the family, children were influenced by parents and caregivers, the study found an overall ability to show and handle feelings, problems of stigma, challenges for the children of prisoners were similar in the four countries | Gravity of offence and length of sentence differed in the countries, children who were not in contact with their imprisoned parents were underrepresented, some children were supported by an NGO, more girls were represented in the study |

| [44] | US | 10 children | 11–16 | Qualitative Interviews with themes such as personal characteristics, family relationships, experiences with parental incarceration and expectations for parental reentry from prison | To examine the coping strategies of young adolescents during and after parental imprisonment | Families with at least one child between 11 and 17 years’ old | Black African American one had another race-ethnicity | Combination of de-identification (avoidance and distance from the imprisoned parent) desensitization (normalizing and minimizing the parent’s situation) and strength through control (finding control in life, distraction and handling), school support, therapy was helpful, caregivers played an important role | Variability in the coping strategies of young people, but a combination of de-identification, desensitization and strength through control, as well as the problem of stigma | Small sample size, mostly paternal incarceration, ethnicity limitations, only six had a parent imprisoned at the time of the interview, only interview at one-time point, recruited children where they could obtain mentoring support |

| [40] | US | 35 children | 1st–10th grade | Non-experimental, qualitative interviews were conducted about a one-year mentoring program; semi-structured questions included topics such as coping, family relationships and context, quantitative measurements from the Youth Self Report, Withdrawn Subscale and Delinquent Subscales | To examine children’s coping strategies related to loss through parental imprisonment and suggesting a need for additional mentoring programmes | Family member in prison, primarily parents | 94,3% minority (African American or Hispanic) | Ineffective, lack of family and social support and children coped on their own, overall variability in coping strategies, avoiding emotions and other people, a greater understanding of the parent’s situation was related to better coping strategies | Findings of stress and trauma, significant results on the CROPS, PTSD, decreased mental health, isolation, kept it inside, a lack of social support for grief, many spent time alone and did not have supportive surroundings. Hard living conditions, a negative correlation between received support and externalizing attitudes, openness in the family was important as was talking about parental imprisonment | Small sample size, geographic/race homogeneity, the data from only one source, difficulties with audiotaping the interviews, no reliable foundation data |

| [39] | SE | Ten children | 7–17 | Qualitative semi-structured interviews included family, school and leisure activities, information about the imprisoned parent, prison visits, contact, contact with helpful organizations and views of the future | To investigate the experiences of children who had parents in prison and to summarize the results with other studies’ in which children suffered from parental problems | Parents sentence had a duration of at least three months, the children knew that the parent was imprisoned | Children in Sweden, other information not provided | Mental strategies, talking about it, spending time with friends, good support at school and NGO’s and peer support, time and age were helpful coping mechanisms. Coping strategies based on resilience were positive ways of dealing with parental imprisonment, family, friends, teachers and health professionals were viewed as helpful | Children are affected by parental imprisonment, expressed feelings of stigma, most participants imagined their future as positive and that problems were improving | Difficulties recruiting participants who had no contact with an NGO, qualitative studies differed in their designs and aims, differed in types as well as descriptive results based on narrative analyses |

| Reference of the Reviewed Study | Location | Study Population (n) | Age or Grade in School | Method | Aims | Description of the Intervention | Ethnicity | Type of Intervention | Key Conclusions | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [43] | US | School students | 5th | A descriptive evaluation of an intervention project | To evaluate a group intervention offering support to elementary school children who had imprisoned parents. The group intervention consisted of eight sessions | 3rd or 5th grade in school, students who had coping problems, lower self-esteem and academic problems | Not provided, but data collection in the US | An eight-session supportive group intervention at school | Structured and theoretically based intervention program, school was important for support. There is a need for workshops for school professionals and school counsellors, who are important for a lead roles | No follow-up, minimal time in group, a small sample size, the need of a more formal evaluation process |

| [37] | US | 15 children and their caregivers | 10–16 | Qualitative, semi-structured interviews and a descriptive summary of the quality of the programme and the relationship between the child and the mentor. Evaluated the four goals from the mentoring programs: Social development, emotional development, friendship and bonding | To describe the outcomes of an evaluation of two mentoring programmes and examine whether the programmes could change children’s attitudes and behaviours | Ages between 10 and 16 years, two members of the interview cohort had to participate (mentor/parent/child) | Not provided, but data collection in the US | Weekly mentoring program, duration from nine months to five years | Mentor was a positive role model, gave stability, improved cognitive and social development, greater openness, more sociability, more self-confidence, signs of happiness, improved school skills | No longitudinal analysis, relationships and expressions were subjective |

| [35] | US | 35 children and their caregivers | 10–11 | Quantitative survey, evaluation | To investigate the l effect of parental imprisonment on children and their families who participate in a mentoring programme with “Seton Youth Shelters” | Having a mentor and experiences of having an imprisoned parent | 45% African American 24% White | A one-to-one mentoring program, once a week | Increased interest in school, improved relationships with their families, and speaking to someone was helpful; positive changes in the children’s behaviours, and increased interest in well-being; 80% agreed or strongly agreed that mentoring had benefits | Families were transient and did not hand in new contact information, there is a need for male mentors; the survey was too long |

| [41] | US | 10 children | 4–5th | Quantitative non-randomized | To investigate a solution-focused mutual aid-group and its impact on children’s well-being | Hispanic American, 4th or 5th grade, had a family member in prison, no psychosis, mental retardation or developmental disorder | Hispanic American | Solution focused and mutual aid group intervention | Significant differences and improvements in the experimental group based on the Hare-Self-Esteem-Scale | Small sample size, no generalization possible, lack of random assignment, difficulty measuring the mental health of children, limited time |

| [36] | UK | 250 children and their caregivers | 7–17 | Qualitative and quantitative data from three-years of the European Commission funded research project COPING, using the Goodman’s Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, the Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale and Kidscreen as well as in-depth interviews | To illustrate results from the COPING project, based on good practice tools for schools to help them support children of imprisoned parents | Families paternal- or maternal imprisonment | Sweden, Romania, Germany and the UK | Support from schools and the need for staff training | Schools were the most important for supporting children and could help with academic performance and counselling, but there was a need for training the teachers and school staff | Not provided, but different in the four countries and all schools reacted differently |

| [34] | US | Children (in general, without a specific number) | Not provided | Descriptive summary of programmes | To discuss and to review services, efforts and interventions to support children who have imprisoned parents | Not provided | Review, but no ethnicity was provided | Mother–daughter intervention activities; grief and loss models of therapeutic intervention | Different interventions had good results (academic and emotional), but there is a need for evidence and gender-specific interventions as well as professional training | Not provided, but data duplication was mentioned |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Heinecke Thulstrup, S.; Eklund Karlsson, L. Children of Imprisoned Parents and Their Coping Strategies: A Systematic Review. Societies 2017, 7, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc7020015

Heinecke Thulstrup S, Eklund Karlsson L. Children of Imprisoned Parents and Their Coping Strategies: A Systematic Review. Societies. 2017; 7(2):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc7020015

Chicago/Turabian StyleHeinecke Thulstrup, Stephanie, and Leena Eklund Karlsson. 2017. "Children of Imprisoned Parents and Their Coping Strategies: A Systematic Review" Societies 7, no. 2: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc7020015