“Activated, but Stuck”: Applying a Critical Occupational Lens to Examine the Negotiation of Long-Term Unemployment in Contemporary Socio-Political Contexts

Abstract

:1. Introduction and Background

2. Methodology and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Frameworks

2.2. Sampling

2.3. Data Collection

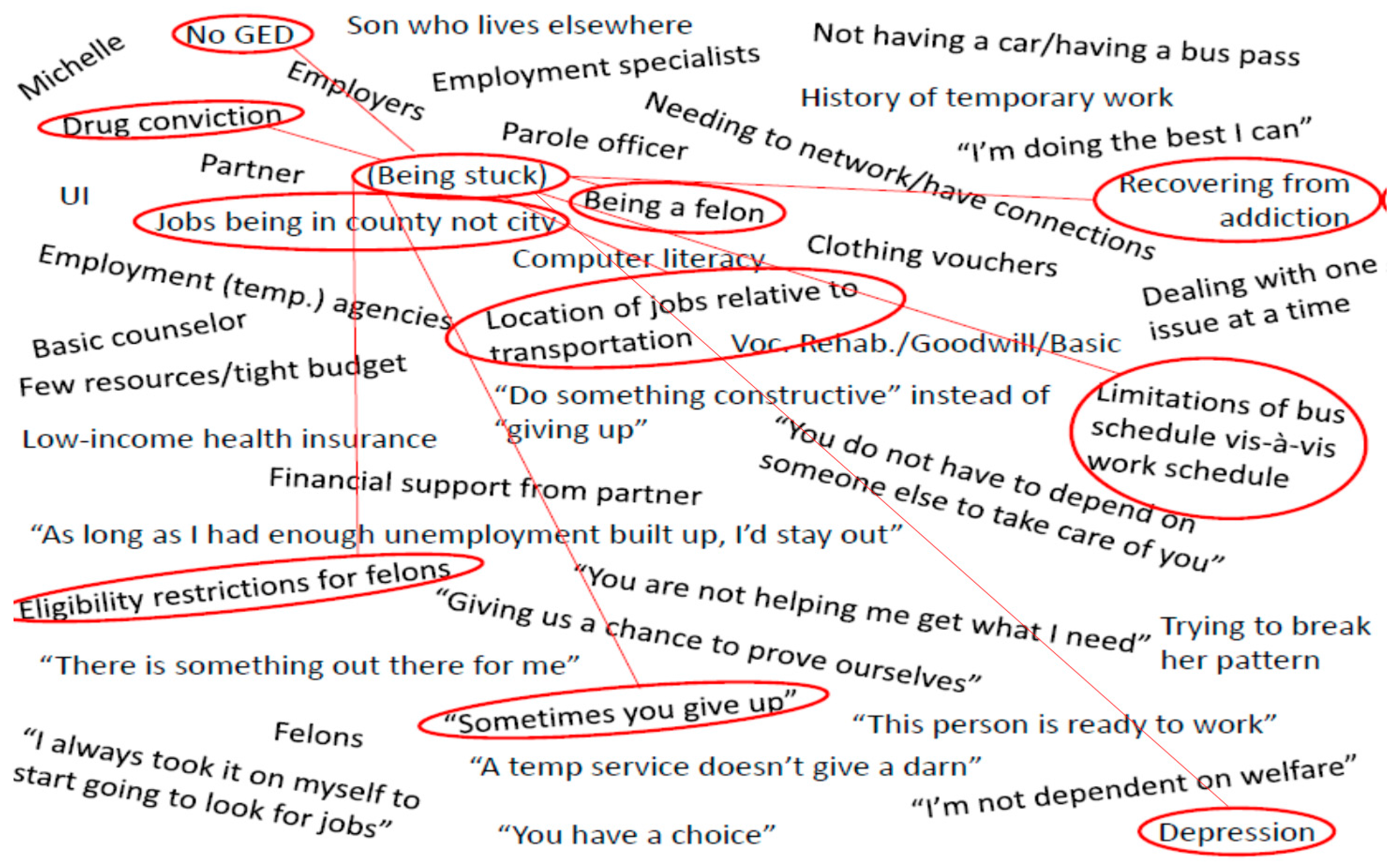

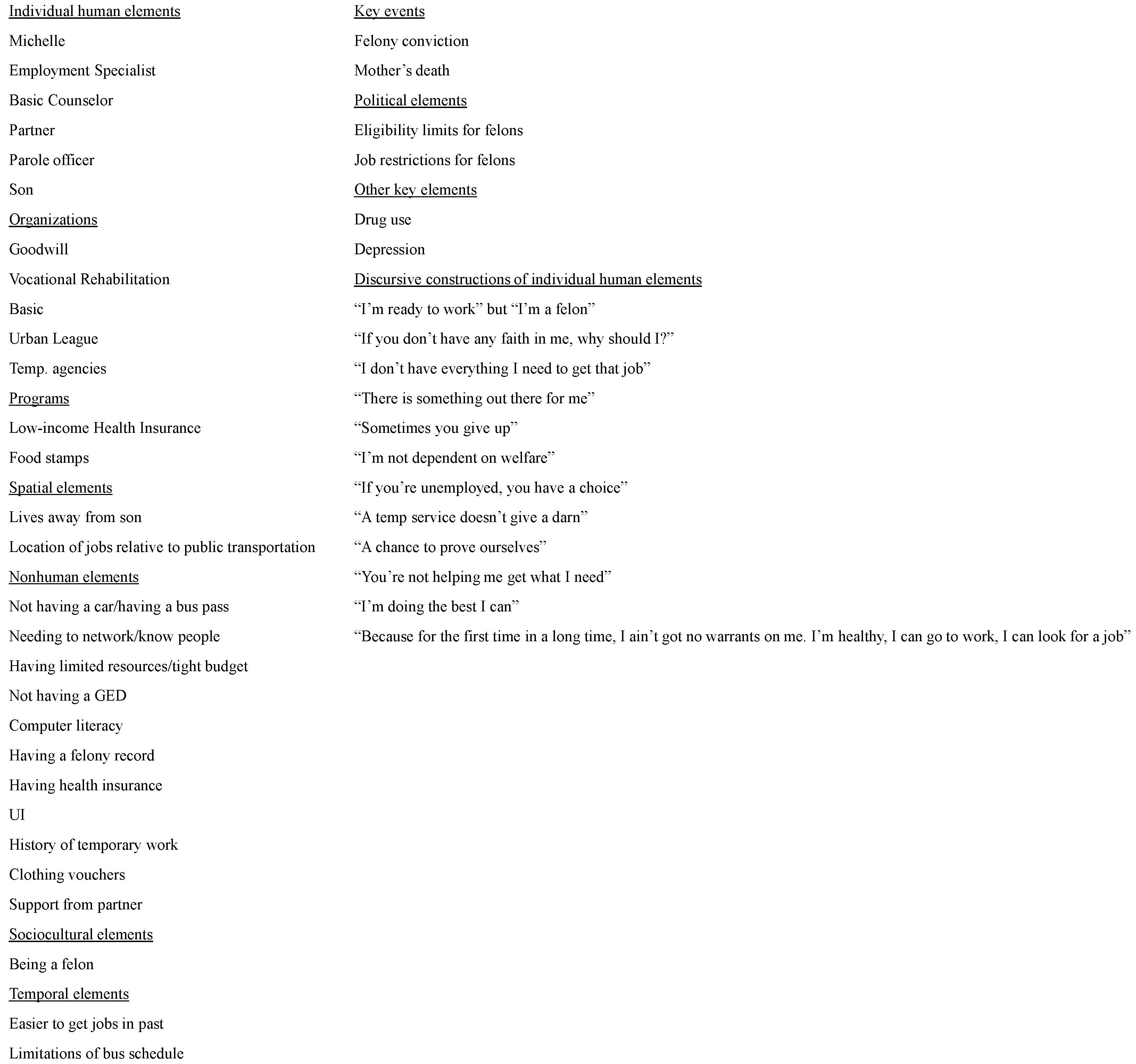

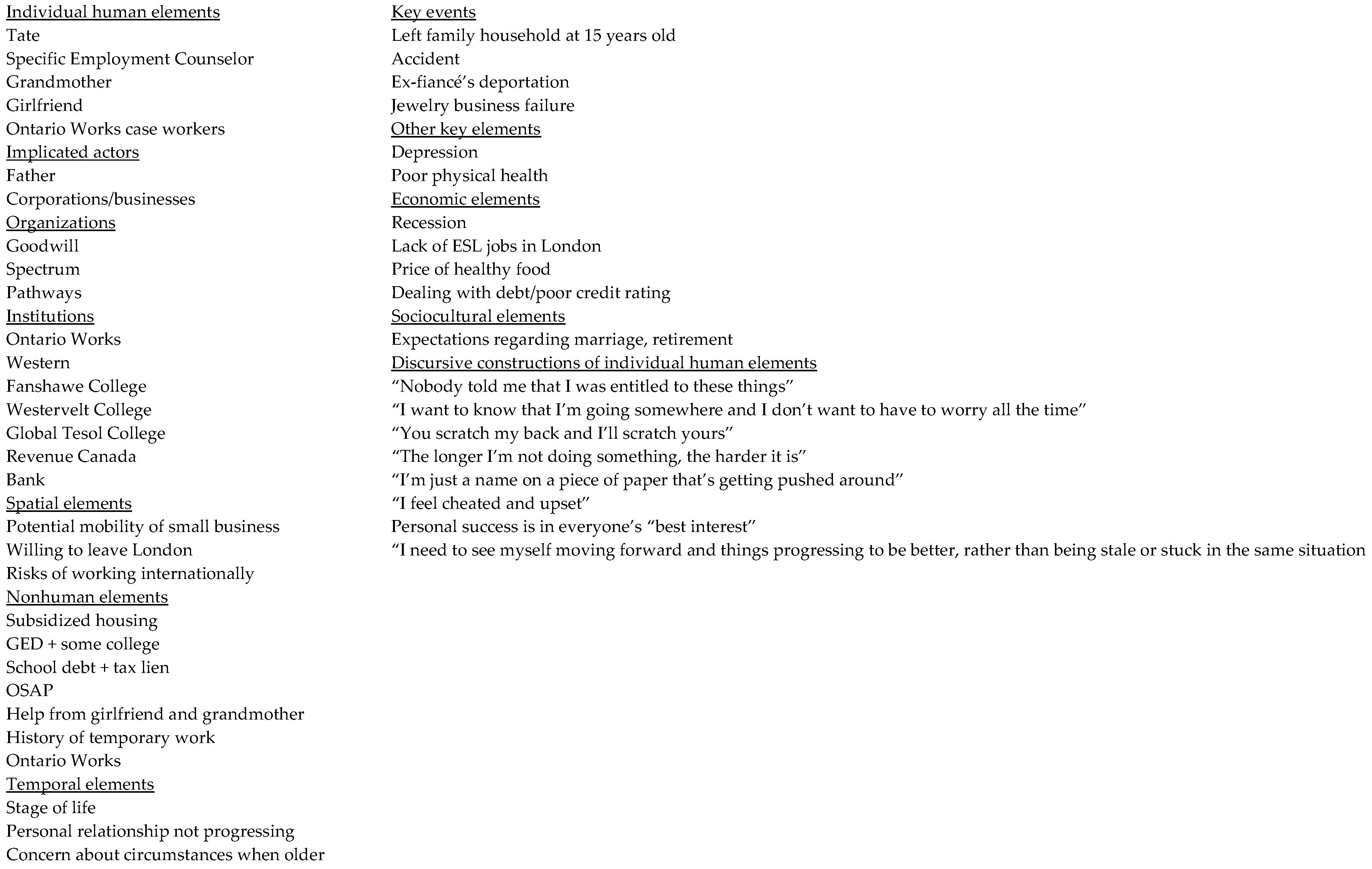

2.4. Analytical Approaches

3. Findings

3.1. The Experience of Being “Activated, But Stuck”

3.2. The Socio-Political Shaping of Being “Activated, But Stuck”

“If I go out and look, I would get discouraged. And I would say, ‘Forget it, this is not working’ so I would go work for a temp service. And sometime I might work for six weeks straight. And then might be off for two weeks. You now, it was back and forth…. I want a full-time job or a permanent job where I know I have a pay check coming in to take care of my bills and my child and myself.”

“You get burnt out. You’re not moving forward and you’re staying at the same spot or you’re back-peddling and then its gets frustrating and you see, I mean you see your first gray hair or you see everybody you grew up with and went to high school or college with and they’re married and with children and you wonder… life is just, its going by.”

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rubin, B.A. Shifting social contracts and the sociological imagination. Soc. Forces 2012, 91, 327–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggan, J. Telling stories of 21st century welfare: The UK Coalition government and the neo-liberal discourse of worklessness and dependency. Crit. Soc. Policy 2012, 32, 383–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blustein, D.L.; Kozan, S.; Connors-Kellgren, A. Unemployment and underemployment: A narrative analysis about loss. J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 82, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). OECD Employment Outlook 2015; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- OECD Data. Long-Term Unemployment Rate. Available online: https://data.oecd.org/unemp/long-term-unemployment-rate.htm (accessed on 14 May 2015).

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. Alternative measures of labor underutilization, Missouri 2012. In News Release 13-446-KAN; US Department of Labor: Kansas City, MO, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Citizens for Public Justice. Labour Market Trends: Third Report in the Poverty Trends Scorecard Series; Citizens for Public Justice: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lightman, E.; Mitchell, A.; Herd, D. Cycling off and on welfare in Canada. J. Soc. Policy 2010, 39, 523–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooley, D. Unemployment, underemployment, and mental health: Conceptualizing employment status as a continuum. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2003, 32, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fevre, R. Still on the scrapheap? The meaning and characteristics of unemployment in prosperous welfare states. Work Employ. Soc. 2011, 25, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharone, O. Why do unemployed Americans blame themselves while Israelis blame the system? Soc. Forces 2013, 91, 1429–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béland, D.; Myles, J. Varieties of federalism, institutional legacies, and social policy: Comparing old-age and unemployment insurance reform in Canada. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2012, 21, S75–S87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oort, M. Making the neoliberal precariat: Two faces of job searching in Minneapolis. Ethnography 2015, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P. From relief to mutual obligation: Welfare rationalities and unemployment in 20th century Australia. J. Sociol. 2001, 37, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riach, K.; Loretto, W. Identity work and the ‘unemployed’ worker: Age, disability and the lived experience of the older unemployed. Work Employ. Soc. 2009, 23, 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gazso, A.; McDaniel, S.A. The risks of being a lone mother on income support in Canada and the USA. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2010, 30, 368–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, T. Seeking a role: Disciplining jobseekers as actors in the labour market. Work Employ. Soc. 2016, 30, 334–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolford, A.; Nelund, A. The responsibilities of the poor: Performing neoliberal citizenship within the bureaucratic field. Soc. Serv. Rev. 2013, 87, 292–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banting, K. Making EI Work: Research from the Mowat Centre Employment Insurance Task Force; Banting, K., Medow, J., Eds.; McGill-Queen’s Press: Kingston, ON, Canada, 2013; Vol. 89, Chapter 1; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Grundy, J.; Laliberte Rudman, D. Deciphering deservedness: Canadian employment insurance reforms in historical perspective. Soc. Policy Admin. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, A. Austerity, social program restructuring, and the erosion of democracy: Examining the 2012 Employment Insurance reforms. Can. Rev. Soc. Policy. 2015, 71, 21–52. [Google Scholar]

- Soss, J.; Fording, R.C.; Schram, S.F. Disciplining the Poor: Neoliberal Paternalism and the Persistent Power of Race; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Baines, D.; Campey, J.; Cunningham, I.; Shields, J. Not profiting from precarity: The work of nonprofit service delivery and the creation of precariousness. Just Labour: A Can. J. Work Soc. 2014, 22, 74–93. [Google Scholar]

- Van Berkel, R. The provision of income protection and activation services for the unemployed in ‘active’ welfare states. An international comparison. J. Soc. Policy 2009, 39, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, M. Researching governmentalities through ethnography: The case of Australian welfare reforms and programs for single parents. Crit. Policy Stud. 2011, 5, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, M. Ethnographies of neoliberal governmentalities: From the neoliberal apparatus to neoliberalism and governmental assemblages. Foucault Stud. 2014, 18, 11–33. [Google Scholar]

- Caswell, D.; Marston, G.; Larsen, J.E. Unemployed citizen or ‘at risk’ client? Classification systems and employment services in Denmark and Australia. Crit. Soc. Policy. 2010, 30, 384–404. [Google Scholar]

- Marston, G.; Mcdonald, C. Feeling motivated yet? Long-term unemployed people’s perspectives on the implementation of workfare in Australia. Aust. J. Soc. Issues 2008, 43, 255–269. [Google Scholar]

- Huot, S. Francophone immigrant integration and neoliberal governance: The paradoxical role of community organizations. J. Occup. Sci. 2013, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laliberte Rudman, D.; Molke, D. Forever productive: The discursive shaping of later life workers in contemporary Canadian newspapers. Work 2009, 32, 377–390. [Google Scholar]

- Laliberte Rudman, D. Enacting the critical potential of occupational science: Problematizing the ‘individualizing of occupation’. J. Occup. Sci. 2013, 20, 298–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Society of Occupational Science. ISOS has a mission. 2009. Available online: http://www.isoccsci.org (accessed on 1 May 2016).

- Laliberte Rudman, D. Occupational terminology: Occupational possibilities. J. Occup. Sci. 2010, 17, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammell, K.W. Self-care, productivity, and leisure, or dimensions of occupational experience? Rethinking occupational “categories”. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 2009, 76, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldrich, R.M.; Dickie, V.A. “It’s hard to plan your day when you have no money”: Discouraged workers’ occupational possibilities and the need to reconceptualize routine. Work 2013, 45, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aldrich, R.M.; Callanan, Y. Insights about studying discouraged workers. J. Occup. Sci. 2011, 18, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitkreuz, R.S.; Williamson, D.L. The self-sufficiency trap: A critical examination of welfare-to-work. Soc. Serv. Rev. 2012, 86, 660–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassiter, L.E.; Campbell, E. What will we have ethnography do? Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, N.; O’Malley, P.; Valverde, M. Governmentality. Annu. Rev. Law Soc. Sci. 2006, 2, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, M. Governing the unemployed self in an active society. Econ. Soc. 1995, 24, 559–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laliberte Rudman, D.; Huot, S. Conceptual Insights for Expanding Thinking Regarding the Situated Nature of Occupation. In Transactional Perspectives on Occupation; Cutchin, M.P., Dickie, V.A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Laliberte Rudman, D. Embracing and enacting an ‘occupational imagination’: Occupational science as transformative. J. Occup. Sci. 2014, 21, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsky, M. Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Hupe, P.; Hill, M. Street-level bureaucracy and public accountability. Public Admin. 2007, 85, 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brodkin, E.Z. Policy work: Street-level organizations under new mangerialism. J. Public Admin. Theory 2011, 21, i253–i277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheek, J. At the margins? Discourse analysis and qualitative research. Qual. Health Res. 2004, 14, 1140–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laliberte Rudman, D.; Dennhardt, S. Discourse Analysis: Using Critical Discourse Analysis to Situate Occupation and Occupational Therapy. In Qualitative Research Methodologies for Occupational Therapy and Occupational Science; Nayar, S., Stanley, M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 137–154. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, A.E. Situational Analysis: Grounded Theory after the Postmodern Turn; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich, R.M.; Laliberte Rudman, D. Situational analysis: A visual analytic approach to unpack the complexity of occupation. J. Occup. Sci. 2016, 23, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njelesani, J.; Gibson, B.E.; Nixon, S.; Cameron, D.; Polatajko, H.J. Towards a critical occupational approach to research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2013, 12, 207–220. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcock, A.A.; Townsend, E.A. Occupational justice. J. Occup. Sci. 2000, 7, 84–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteford, G. Occupational deprivation: Global challenge in the new millennium. Brit. J. Occup. Ther. 2000, 63, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polatajko, H.J.; Townsend, E.A. Enabling Occupation II: Advancing an Occupational Therapy Vision for Health, well-being & Justice Through Occupation; Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, K.; Richardson, V.E.; Fields, N.L.; Harootyan, R. Inclusion or exclusion? Exploring barriers to employment for low-income older adults. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2013, 56, 318–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, E.D. Managing age discrimination: An examination of the techniques used when seeking employment. Gerontologist 2009, 49, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handy, J.; Davy, D. Gendered ageism: Older women's experiences of employment agency practices. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resou. 2007, 45, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huot, S.; Laliberte Rudman, D. Extending beyond qualitative interviewing to illuminate the tacit nature of everyday occupation: Occupational mapping and participatory occupational methods. Occup. Ther. J. Res. Occ. Par. Health 2015, 35, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlan, J.N.; Bundy, A.C. Development and validation of the modified occupational questionnaire. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2011, 65, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pseudonym | Site | Age | Gender | Educational Level | Length of Unemployment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JR | U.S. | 40s | Male | Less than high school | 5 years |

| Chris | U.S. | 50s | Male | High school equivalency | 1 year |

| Sheila | U.S. | Mid-40s | Female | High school diploma | 1 year |

| Michelle | U.S. | Late 40s | Female | Less than high school | Last full-time job 5 years ago |

| Kevin | Canada | Mid-30s | Male | High school diploma | 5 years |

| Tate | Canada | Late 30s | Male | College certificate | 5 years |

| Denise | Canada | Early 40s | Female | High school diploma | Last full time job 5 years ago |

| Eileen | Canada | Early 60s | Female | College certificate | Last full time job 15 years ago |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Laliberte Rudman, D.; Aldrich, R. “Activated, but Stuck”: Applying a Critical Occupational Lens to Examine the Negotiation of Long-Term Unemployment in Contemporary Socio-Political Contexts. Societies 2016, 6, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc6030028

Laliberte Rudman D, Aldrich R. “Activated, but Stuck”: Applying a Critical Occupational Lens to Examine the Negotiation of Long-Term Unemployment in Contemporary Socio-Political Contexts. Societies. 2016; 6(3):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc6030028

Chicago/Turabian StyleLaliberte Rudman, Debbie, and Rebecca Aldrich. 2016. "“Activated, but Stuck”: Applying a Critical Occupational Lens to Examine the Negotiation of Long-Term Unemployment in Contemporary Socio-Political Contexts" Societies 6, no. 3: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc6030028