Selective Flotation of Cassiterite from Calcite with Salicylhydroxamic Acid Collector and Carboxymethyl Cellulose Depressant

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

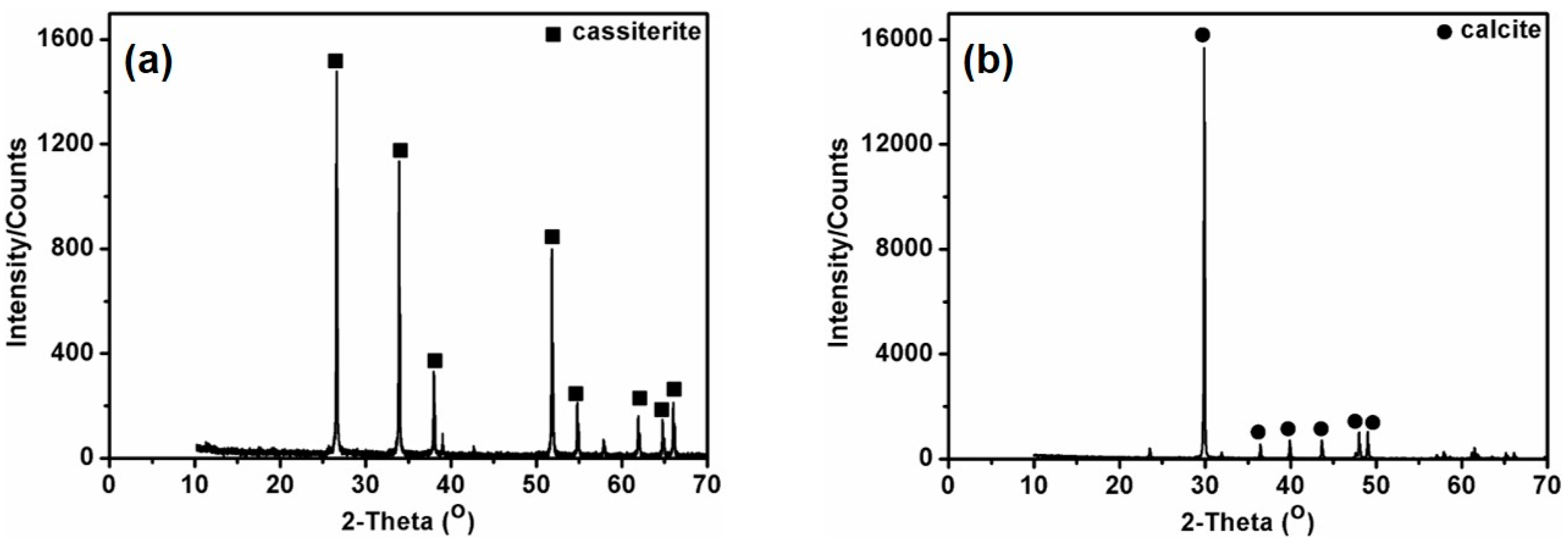

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Flotation Tests

2.3. Zeta Potential Measurements

2.4. FTIR Spectroscopy Measurements

2.5. XPS Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

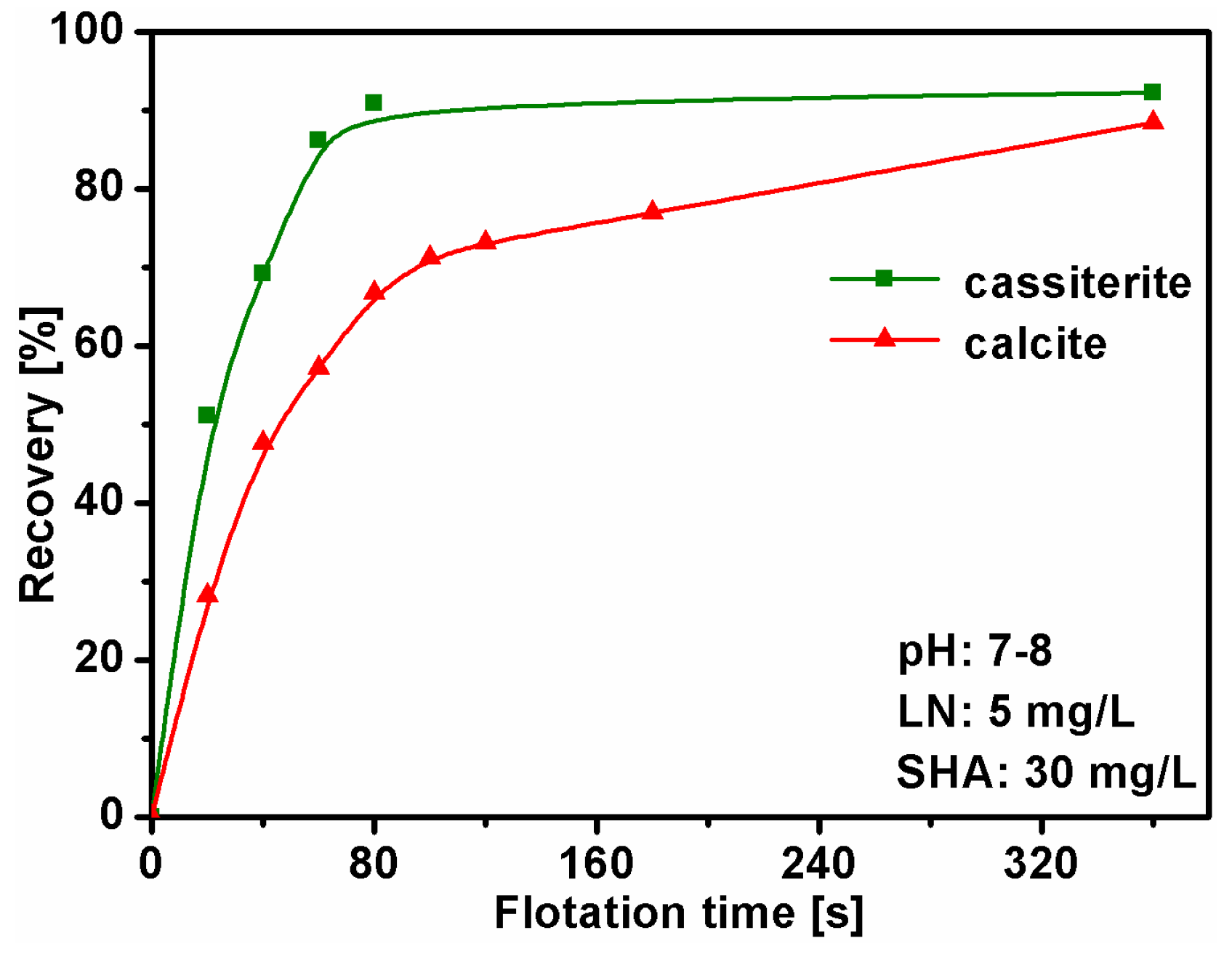

3.1. Single Mineral Flotation Experiments

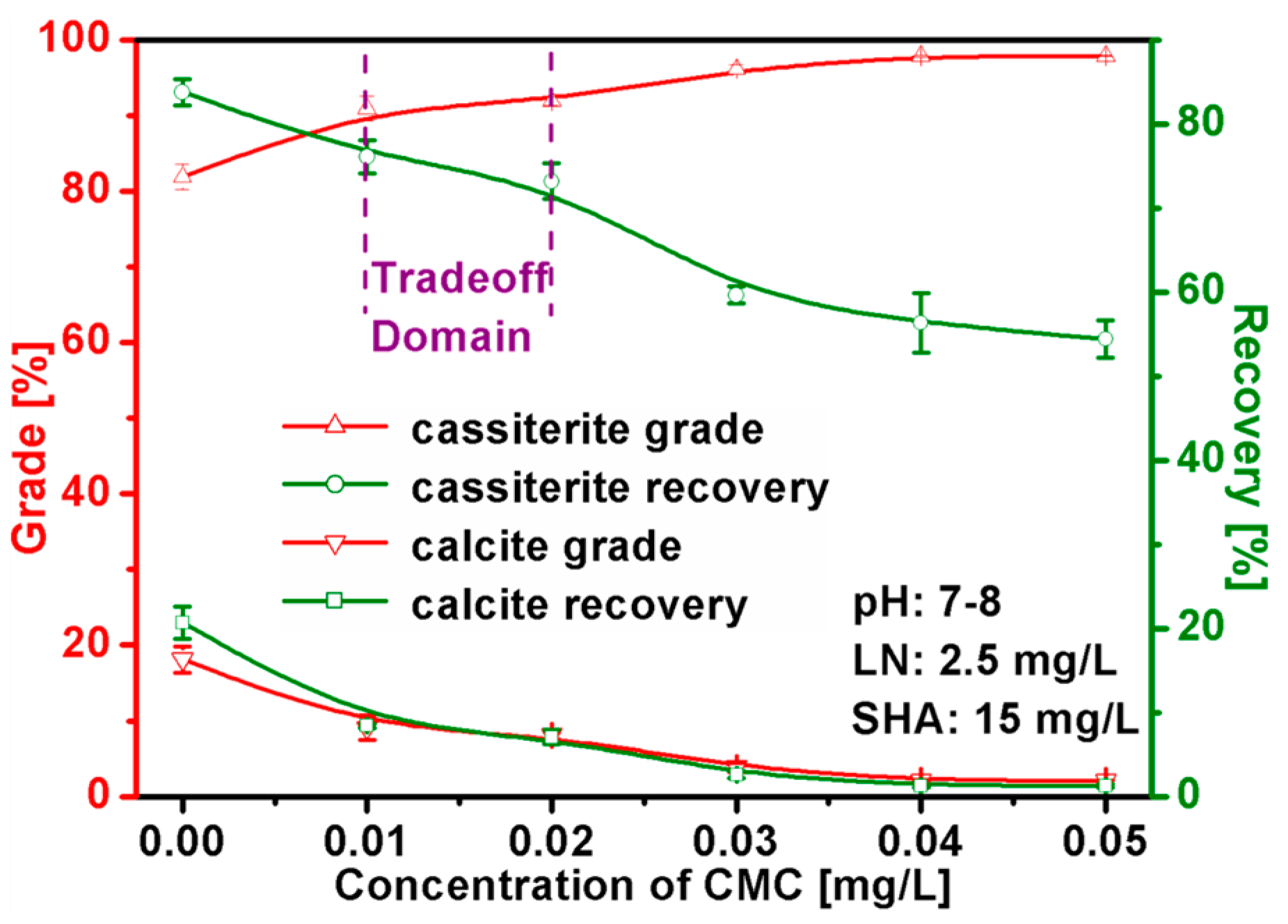

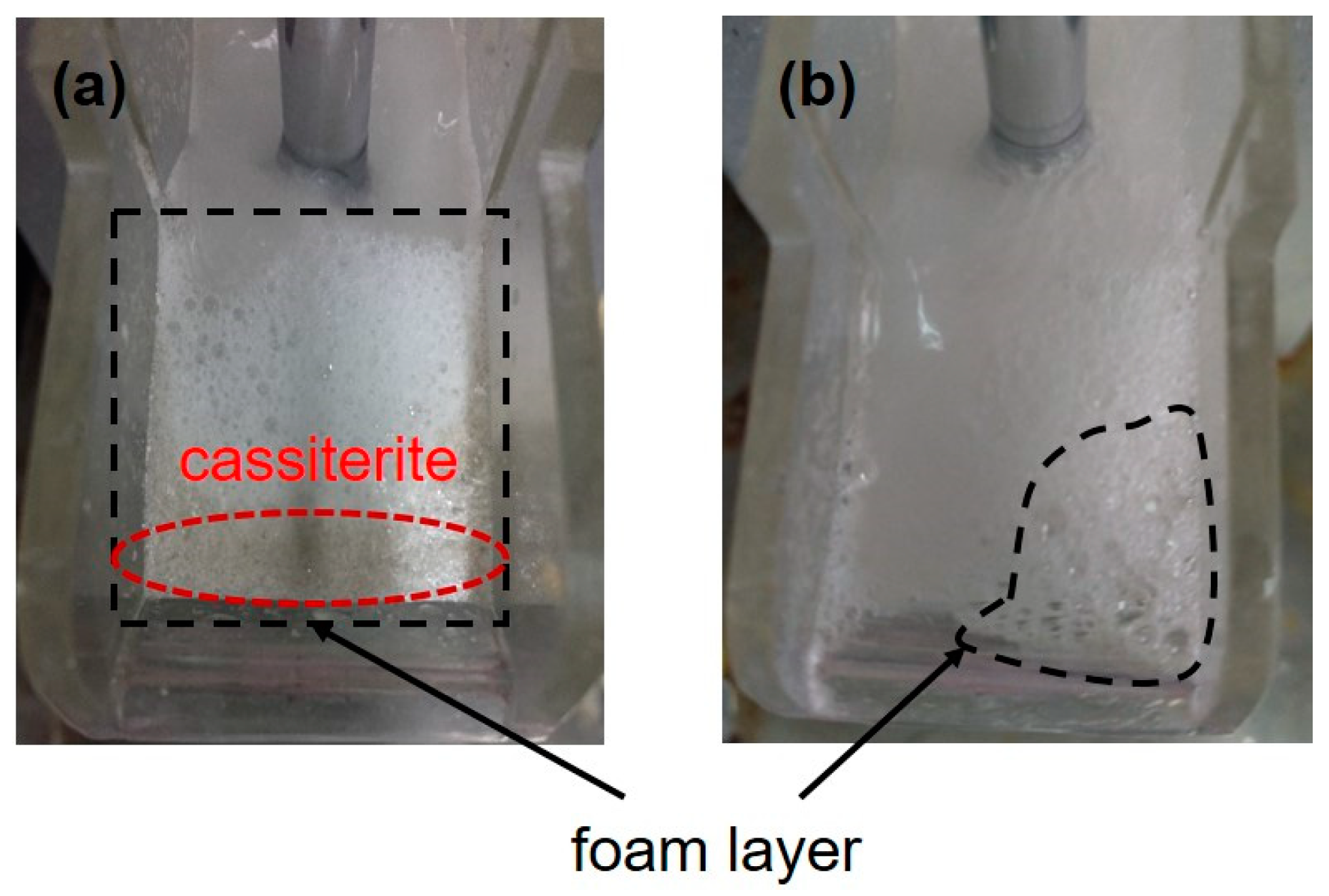

3.2. Mixed Binary Mineral Flotation Experiments

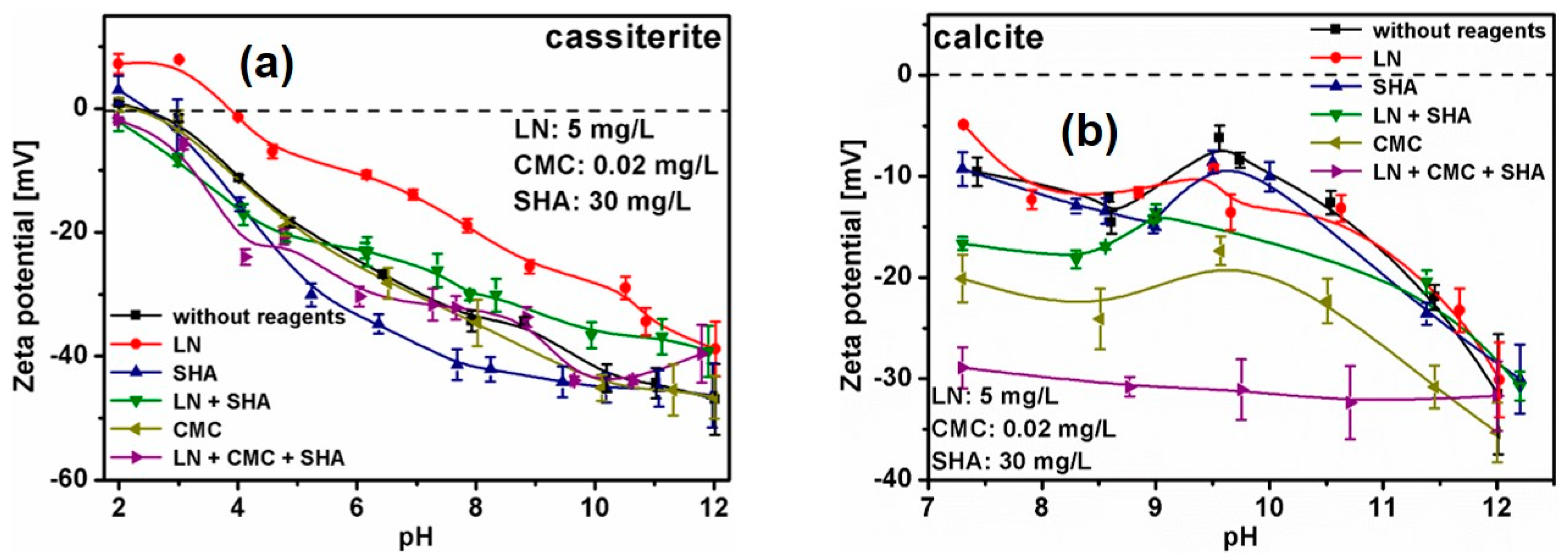

3.3. Zeta Potential Measurements

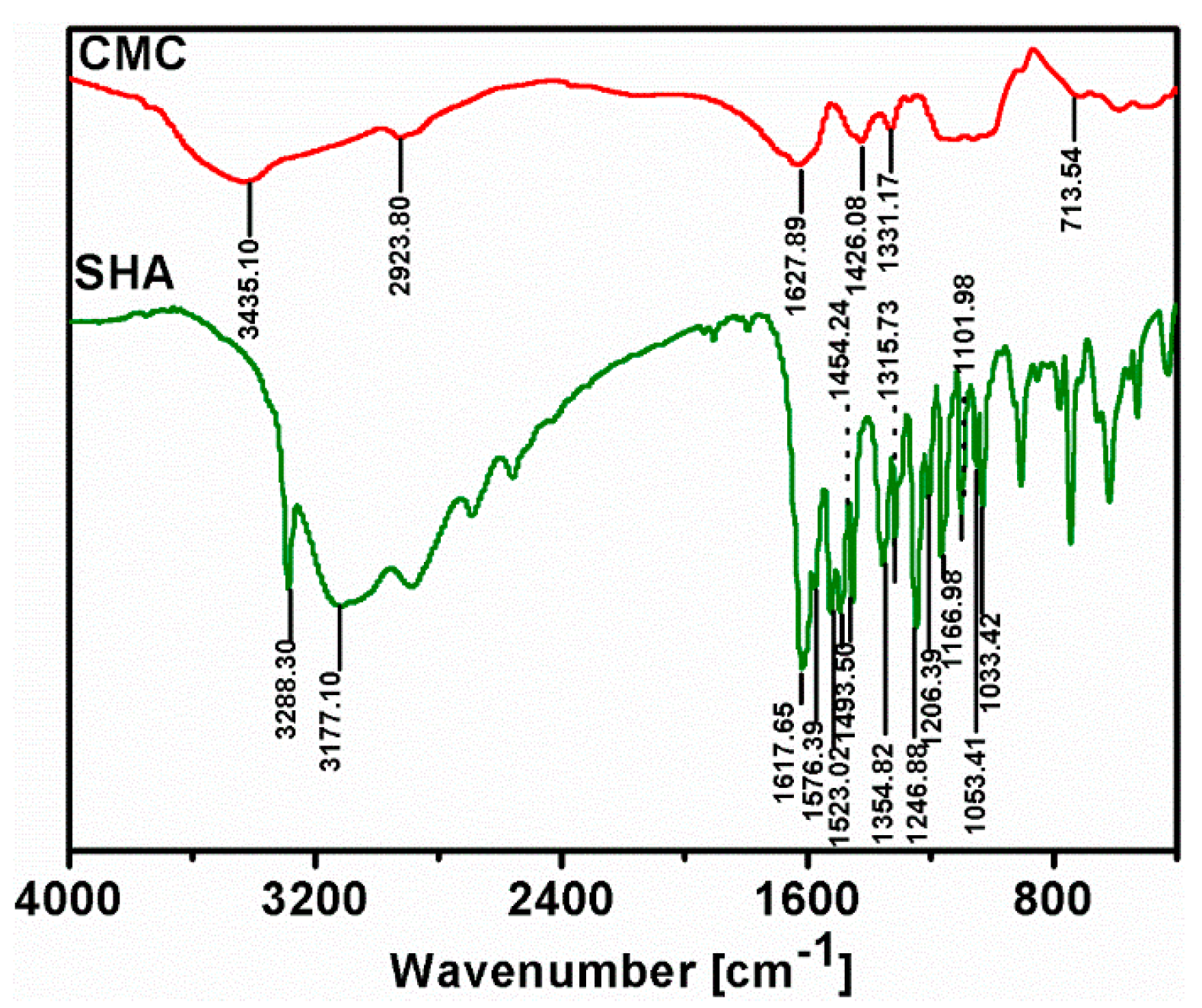

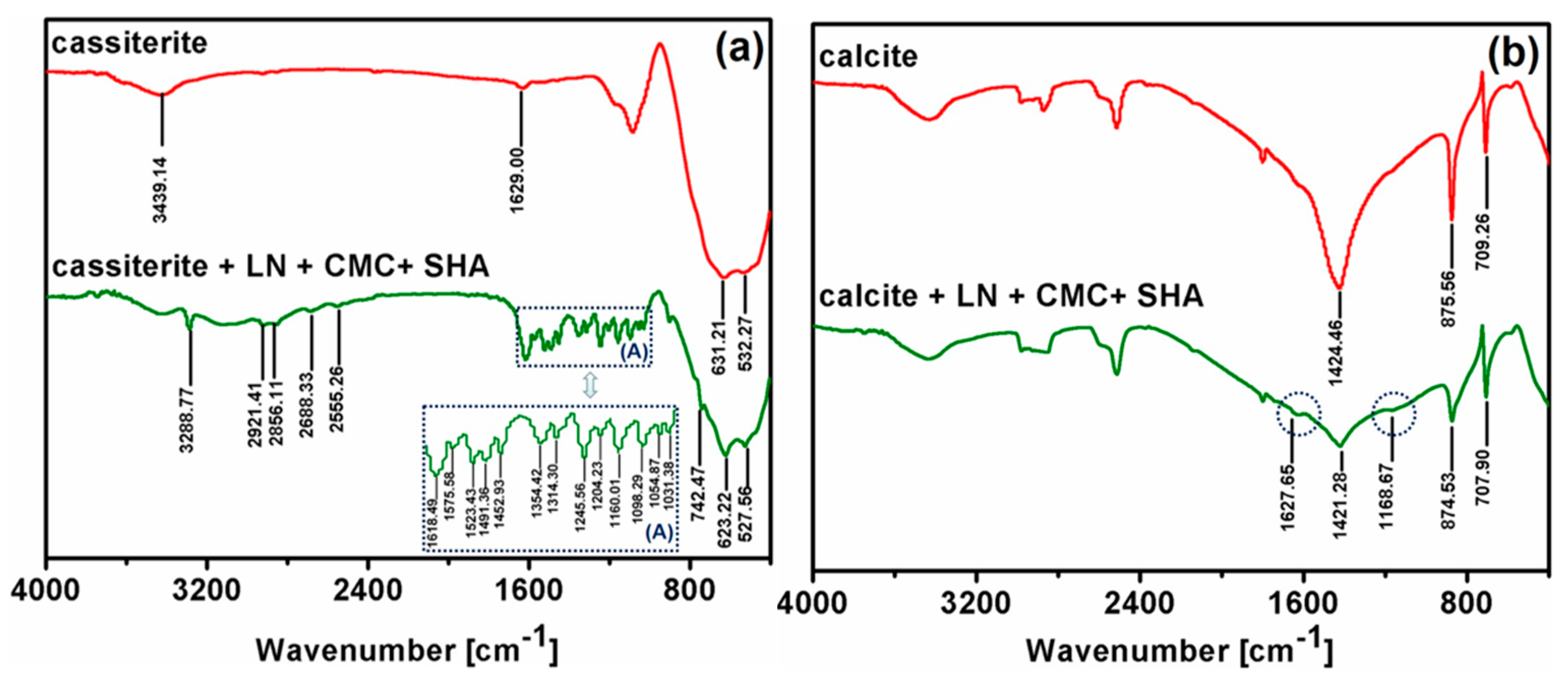

3.4. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy Analysis

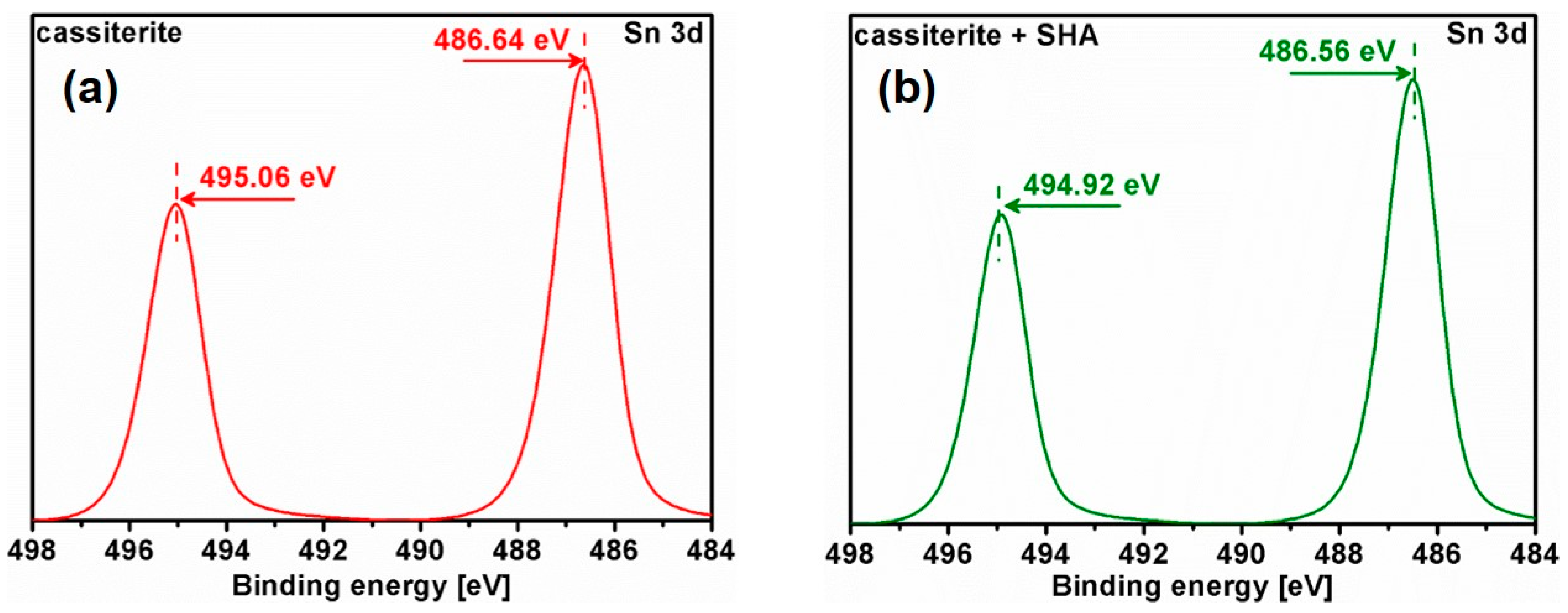

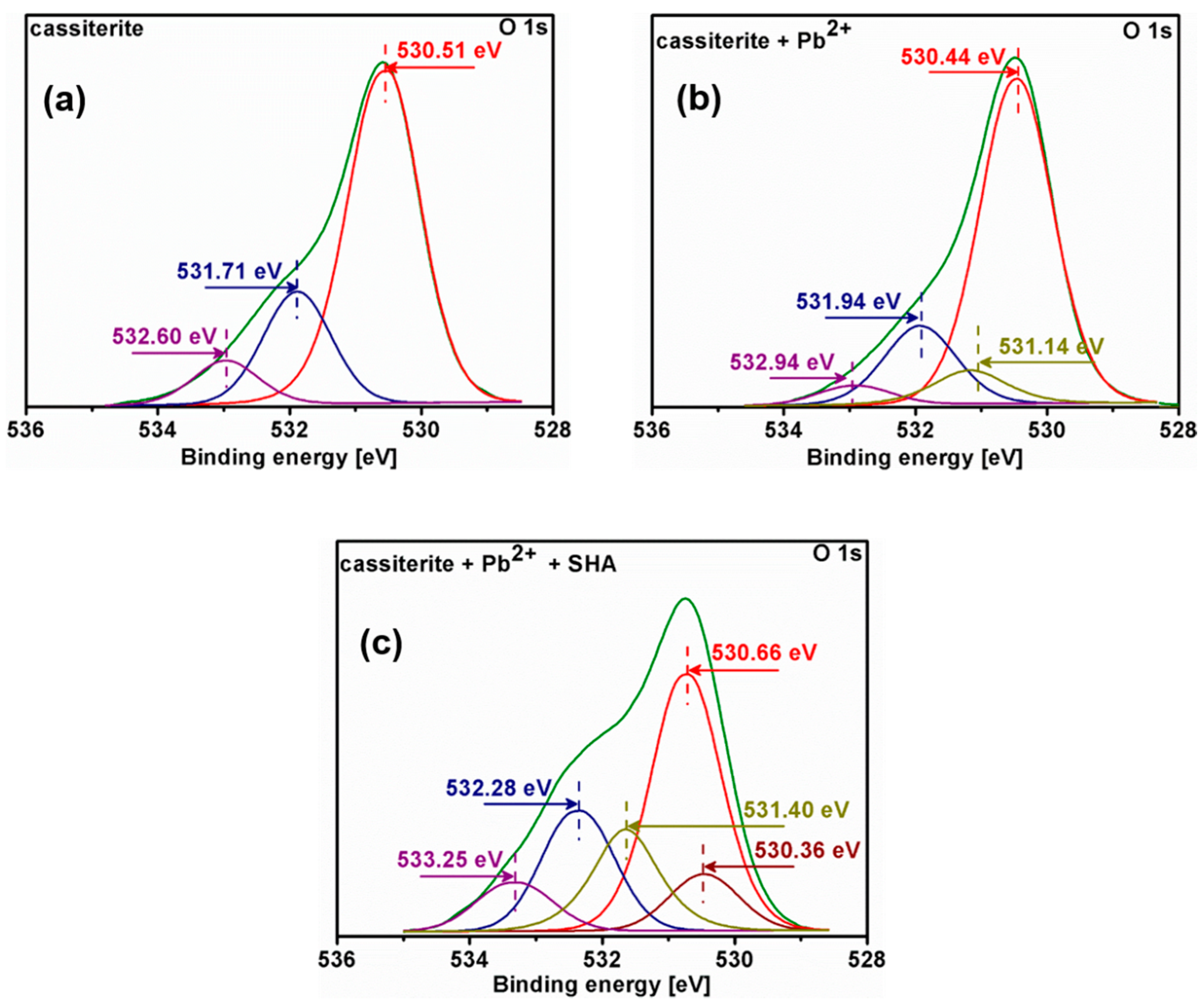

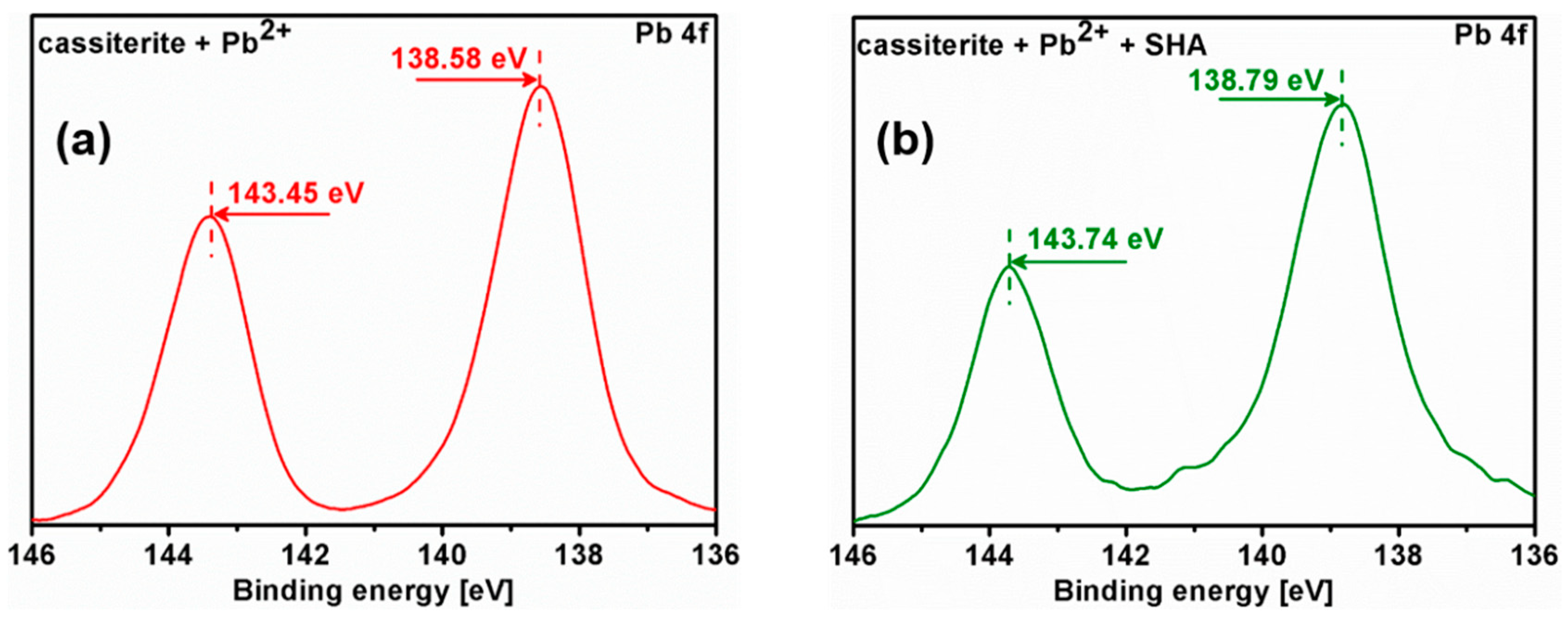

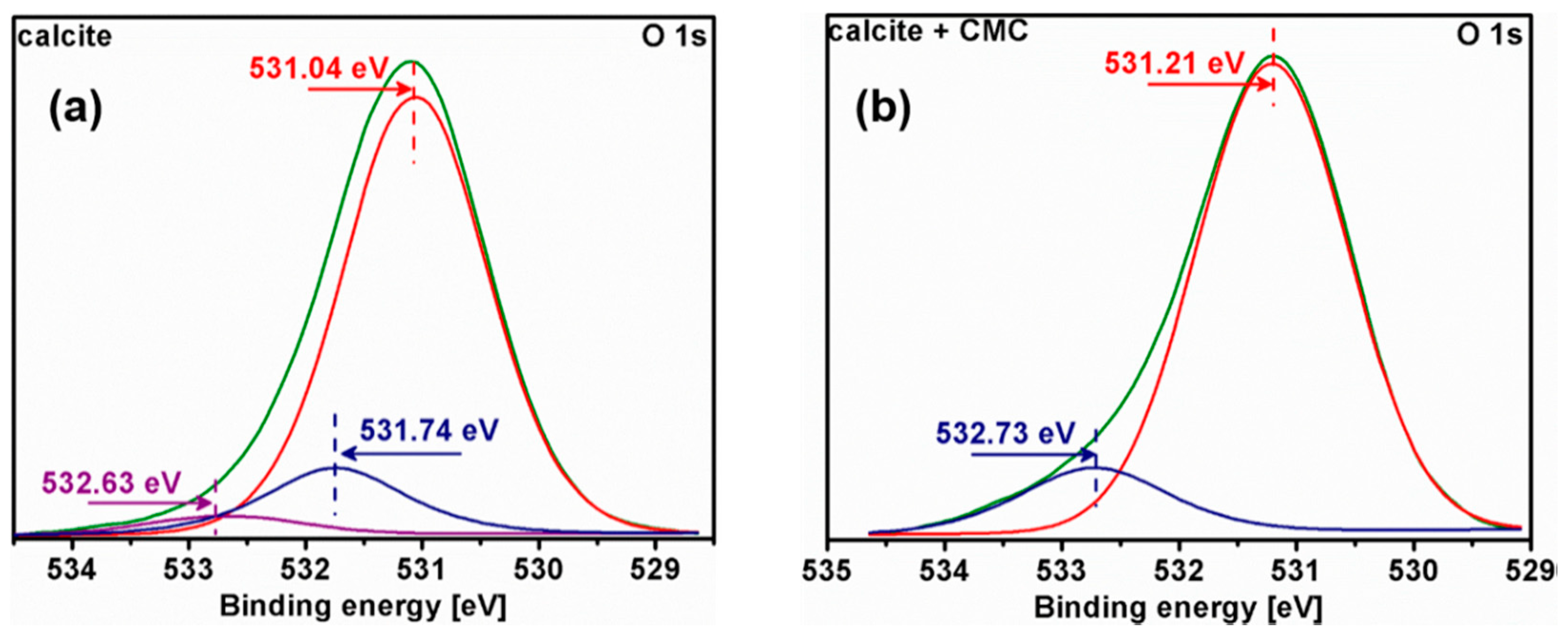

3.5. X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Spencer, M.J.S. Gas sensing applications of 1D-nanostructured zinc oxide: Insights from density functional theory calculations. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2012, 57, 437–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechthold, P.; Pronsato, M.E.; Pistonesi, C. DFT study of CO adsorption on Pd-SnO2 (110) surfaces. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 347, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, M.; Huang, F.; Cui, L.; Huang, P.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Y. Hydrothermal synthesis, structural characteristics, and enhanced photocatalysis of SnO2/alpha-Fe2O3 semiconductor nanoheterostructures. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhanjana, G.; Dilbaghi, N.; Kumar, R.; Umar, A.; Kumar, S. SnO2 quantum dots as novel platform for electrochemical sensing of cadmium. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 169, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angadi, S.I.; Sreenivas, T.; Jeon, H.S.; Baek, S.H.; Mishra, B.K. A review of cassiterite beneficiation fundamentals and plant practices. Miner. Eng. 2015, 70, 178–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, R.G.; Machunter, D.M.; Gates, P.J.; Palmer, M.K. Gravity separation of ultrafine (−0.1 mm) minerals using spiral separators. Miner. Eng. 2000, 13, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, J.S. Physical analysis and modeling of the falcon concentrator for beneficiation of ultrafine particles. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2013, 121, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gruner, H.; Bilsing, U. Cassiterite flotation using styrene phosphonic acid to produce high-grade concentrates at high recoveries from finely disseminated ores comparison with other collectors and discussion of effective circuit configurations. Miner. Eng. 1992, 5, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Wen, S.; Zhao, W.; Chen, Y. Effect of calcium ions on adsorption of sodium oleate onto cassiterite and quartz surfaces and implications for their flotation separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 200, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofor, O.; Nwoko, C. Oleate flotation of a Nigerian baryte: The relation between flotation recovery and adsorption density at varying oleate concentrations, pH, and temperatures. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1997, 186, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.; Xie, L.; Cui, X.; Hu, Y.; Sun, W.; Zeng, H. Probing anisotropic surface properties and surface forces of fluorite crystals. Langmuir 2018, 34, 2511–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Gao, Z. Effect of grinding media on the surface property and flotation behavior of scheelite particles. Powder Technol. 2017, 322, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenivas, T.; Padmanabhan, N.P.H. Surface chemistry and flotation of cassiterite with alkyl hydroxamates. Colloids Surf. A. 2002, 205, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.Q.; Zhu, J.G. Selective flotation of cassiterite with benzohydroxamic acid. Miner. Eng. 2006, 19, 1410–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.; Xu, Y.; Liu, H.; Ren, L.; Yang, C. Flotation and surface behavior of cassiterite with salicylhydroxamic acid. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2011, 50, 10778–10783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Liu, R.; Gao, Z.; Chen, P.; Han, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, C.; Sun, W.; Hu, Y. Activation mechanism of Fe (iii) ions in cassiterite flotation with benzohydroxamic acid collector. Miner. Eng. 2018, 119, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Zhang, C.; Han, H.; Liu, R.; Gao, Z.; Chen, P.; He, J.; Hu, Y.; Sun, W.; Yuan, D. Novel insights into adsorption mechanism of benzohydroxamic acid on lead (ii)-activated cassiterite surface: An integrated experimental and computational study. Miner. Eng. 2018, 122, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Hu, Y.; Sun, W.; Liu, R. Study on the mechanism and application of a novel collector-complexes in cassiterite flotation. Colloids Surf. A 2017, 522, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Gao, Z.; Sun, W.; Han, H.; Sun, L.; Hu, Y. Activation role of lead ions in benzohydroxamic acid flotation of oxide minerals: New perspective and new practice. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 529, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Hu, Y.-H.; Sun, W. Effect and mechanism of octanol in cassiterite flotation using benzohydroxamic acid as collector. Trans. Nonferrous Metal. Soc. 2016, 26, 3253–3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Zhao, W.; Wen, S.; Cao, Q. Activation mechanism of lead ions in cassiterite flotation with salicylhydroxamic acid as collector. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 178, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hu, Y.; Sun, W.; Li, X.; Cao, C.; Liu, R.; Yue, T.; Meng, X.; Guo, Y.; Wang, J. Fatty acid flotation versus bha flotation of tungsten minerals and their performance in flotation practice. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2017, 159, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Thyabat, S. Empirical evaluation of the role of sodium silicate on the separation of silica from jordanian siliceous phosphate. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2009, 67, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Hu, Y.; Han, H.; Sun, W.; Wang, R.; Wang, J. Selective flotation of scheelite from calcite using Al-Na2SiO3 polymer as depressant and Pb-BHA complexes as collector. Miner. Eng. 2018, 120, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Bai, D.; Sun, W.; Cao, X.; Hu, Y. Selective flotation of scheelite from calcite and fluorite using a collector mixture. Miner. Eng. 2015, 72, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Gao, Z.; Sun, W.; Hu, Y. Selective flotation of scheelite from calcite: A novel reagent scheme. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2016, 154, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gao, Z.; Gao, Y.; Hu, Y.; Sun, W. Flotation separation of scheelite from calcite using mixed cationic/anionic collectors. Miner. Eng. 2016, 98, 261–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Gao, Z.; Sun, W.; Yin, Z.; Wang, J.; Hu, Y. Adsorption of a novel reagent scheme on scheelite and calcite causing an effective flotation separation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 512, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parolis, L.A.S.; van der Merwe, R.; Groenmeyer, G.V.; Harris, P.J. The influence of metal cations on the behaviour of carboxymethyl celluloses as talc depressants. Colloids Surf. A 2008, 317, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Shi, Q.; Li, Q.; Ou, L.; Ouyang, K. Effect of calcium ionic concentrations on the adsorption of carboxymethyl cellulose onto talc surface: Flotation, adsorption and afm imaging study. Powder Technol. 2018, 331, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdukova, E.; Van Leerdam, G.C.; Prins, F.E.; Smeink, R.G.; Bradshaw, D.J.; Laskowski, J.S. Effect of calcium ions on the adsorption of CMC onto the basal planes of new york talc—A ToF-SIMS study. Miner. Eng. 2008, 21, 1020–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khraisheh, M.; Holland, C.; Creany, C.; Harris, P.; Parolis, L. Effect of molecular weight and concentration on the adsorption of CMC onto talc at different ionic strengths. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2005, 75, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parolis, L.A.S.; van der Merwe, R.; van Leerdam, G.C.; Prins, F.E.; Smeink, R.G. The use of ToF-SIMS and microflotation to assess the reversibility of binding of cmc onto talc. Miner. Eng. 2007, 20, 970–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Gao, Z.; Han, H.; Sun, W.; Hu, Y. Improved flotation separation of cassiterite from calcite using a mixture of lead (ii) ion/benzohydroxamic acid as collector and carboxymethyl cellulose as depressant. Miner. Eng. 2017, 113, 68–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Hu, Y.; Sun, W.; Gao, Z.; Tian, M. Selective recovery of mushistonite from gravity tailings of copper–tin minerals in tajikistan. Minerals 2017, 7, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuri, O.S.; Allahkarami, E.; Irannajad, M.; Abdollahzadeh, A. Estimation of selectivity index and separation efficiency of copper flotation process using ann model. Geosyst. Eng. 2016, 20, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Xu, L.; Deng, W.; Jiang, H.; Gao, Z.; Hu, Y. Adsorption mechanism of new mixed anionic/cationic collectors in a spodumene-feldspar flotation system. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2017, 164, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wang, L.; Gu, C.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Shim, J.J. Preparation of porous SnO2 microcubes and their enhanced gas-sensing property. Sens. Actuators B 2015, 207, 782–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwoka, M.; Waczyńska, N.; Kościelniak, P.; Sitarz, M.; Szuber, J. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy and thermal desorption spectroscopy comparative studies of l-cvd SnO2 ultra thin films. Thin Solid Films 2011, 520, 913–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, E.L.; Patthey, L.; Steinemann, S.G. Clean and hydroxylated rutile TiO2 (110) surfaces studied by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Surf. Sci. 1996, 352–354, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göpel, W.; Anderson, J.A.; Frankel, D.; Jaehnig, M.; Phillips, K.; Schäfer, J.A.; Rocker, G. Surface defects of TiO2 (110): A combined xps, xaes and els study. Surf. Sci. 1984, 139, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.H.; Park, J.Y.; Hwang, A.R.; Kang, Y.C. Spectroscopic and morphological investigation of Co3O4 microfibers produced by electrospinning process. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2012, 33, 1242–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punginsang, M.; Wisitsora-At, A.; Tuantranont, A.; Phanichphant, S.; Liewhiran, C. Effects of cobalt doping on nitric oxide, acetone and ethanol sensing performances of fsp-made SnO2 nanoparticles. Sens. Actuators B 2015, 210, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giudici, G.D.; Rossi, A.; Fanfani, L.; Lattanzi, P. Mechanisms of galena dissolution in oxygen-saturated solutions: Evaluation of PH effect on apparent activation energies and mineral-water interface. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2005, 69, 2321–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippova, I.V.; Filippov, L.O.; Lafhaj, Z.; Barres, O.; Fornasiero, D. Effect of calcium minerals reactivity on fatty acids adsorption and flotation. Colloids Surf. A 2018, 545, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stipp, S.L.S. Toward a conceptual model of the calcite surface: Hydration, hydrolysis, and surface potential. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1999, 63, 3121–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Li, C.; Sun, W.; Hu, Y. Anisotropic surface properties of calcite: A consideration of surface broken bonds. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2017, 520, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Gao, Z.; Khoso, S.A.; Gao, J.; Sun, W.; Pu, W.; Hu, Y. Selective adsorption of benzhydroxamic acid on fluorite rendering selective separation of fluorite/calcite. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 435, 752–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Q.; Hu, Y.; Tang, H.; Sun, W.; Gao, Z. Preparation of α-CaSO4·½H2O with tunable morphology from flue gas desulphurization gypsum using malic acid as modifier: A theoretical and experimental study. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 530, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Reagent Schedule | Salicylhydroxamic Acid | Benzohydroxamic Acid | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without CMC | With CMC | Without CMC | with CMC | |

| Selectivity index (SI) | 5.19 | 4.68 | - | 2.79 [34] |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tian, M.; Gao, Z.; Ji, B.; Fan, R.; Liu, R.; Chen, P.; Sun, W.; Hu, Y. Selective Flotation of Cassiterite from Calcite with Salicylhydroxamic Acid Collector and Carboxymethyl Cellulose Depressant. Minerals 2018, 8, 316. https://doi.org/10.3390/min8080316

Tian M, Gao Z, Ji B, Fan R, Liu R, Chen P, Sun W, Hu Y. Selective Flotation of Cassiterite from Calcite with Salicylhydroxamic Acid Collector and Carboxymethyl Cellulose Depressant. Minerals. 2018; 8(8):316. https://doi.org/10.3390/min8080316

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, Mengjie, Zhiyong Gao, Bin Ji, Ruiying Fan, Runqing Liu, Pan Chen, Wei Sun, and Yuehua Hu. 2018. "Selective Flotation of Cassiterite from Calcite with Salicylhydroxamic Acid Collector and Carboxymethyl Cellulose Depressant" Minerals 8, no. 8: 316. https://doi.org/10.3390/min8080316