1. Introduction

This research aims to better understand individuals’ perceptions of water and how it impacts individuals’ beliefs and actions toward water. Perceptions are the lens in which the participants identify water, and beliefs and actions are how the individuals react based on their perceptions; in this research, perceptions refers to how the individual perceives water i.e., as a commodity, a human right, private resource, public resource and/or natural resource. The authors asked the question: Does the way an individual perceives water influence consumption and conservation of water, and sentiments towards control and allocation of water? Our study differs from existing research by addressing perceptions of water itself, and comparing those perceptions/beliefs about water consumption, conservation and management.

Various studies have used surveys to collect information on public attitudes and perceptions of water [

1]. In regards to water quality, many studies have found that concern for pollution in water is increasing, particularly in drinking water [

2,

3]. This has led to a steady increase in the consumption of bottled water, as participants in these studies have indicated they are not happy with their tap water [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Doria found that perceptions of drinking water quality are highly influenced by organoleptic factors, such as taste and odour [

8]. Research on willingness to pay for improved water sources in order to get better quality water has found a range of results. People’s willingness to pay for improved water sources ranges from a distinct lack of willingness to pay [

9,

10] to the majority being willing to pay a good deal more than what is currently being charged [

11,

12]. Recycling waste water for direct use is not a new idea, nor are the studies that have looked at people’s perceptions of it. These studies have found that better understanding of how the water is recycled, including the treatment process and how it flows back into the system is crucial to uptake [

13,

14]. One example of a study that looked at attitudes towards water quality is by Syme and Williams, who compared attitudes to psychological and experiential factors, attitudes and demographics [

15].

However there are several topics related to public attitudes and perceptions of water that have not been well researched. These topics include people’s perceptions of the value of water, water consumption, water regulations, the water footprint, and water scarcity Although studies exist that covered attitudes these studies did not ask exactly how participants perceive water, meaning what they consider water to be (

i.e., a natural resource, a commodity, a public resource,

etc.). Instead, many surveys simply make assumptions about how an individual perceives water [

1]. Most of the surveys assume water is recognized as a natural resource. The following topics are inadequately covered in current water surveys.

Some surveys ask questions about the value of water [

12,

16,

17]. How people value water is an important concern, particularly when addressing mitigation of overconsumption of water. While there is willingness to pay for water surveys, the value of water does not necessarily fall within the measurements used in willingness to pay estimates. Evaluations of people’s perceptions of the value of water external to willingness to pay have not been well documented. In this research survey, the value of water was related to other values, such as aesthetic and health related values.

Surveys that inquire about the different uses of water do not include questions about what the individual thinks about the way he/she is using water, or the way he/she thinks it should be used. It is important to understand not only how individuals use water, but how they believe it should be used, and moreover, what they perceive as necessary (i.e., water for drinking, for sanitation, etc.) water use. Questions in the survey address this.

There has been some research regarding how water should be controlled and allocated. For example, surveys conducted for the European Union have focused primarily on private

versus a public water distribution system [

18]. However, there are many other questions related to the control and allocation of water that have not yet been addressed, such as who should be in control (

i.e., local

versus national governments). The survey used in this research addresses those questions, and relates them to the individuals’ perceptions of water.

Only one survey was found that included questions on the water footprint, and no surveys were found that looked at people’s perceptions or attitudes toward the water footprint [

19]. The water footprint is a measurement of water consumption akin to the carbon footprint [

20]. This survey includes an explanation and questions about the water footprint.

Water scarcity issues have been surveyed mostly in water scarce areas [

21]. In the RBC survey of Canadian water attitudes, there are only two questions related to water quantity, and neither addresses concern around running out of water [

22]. In Quebec, there has been several studies on people’s perceptions of water quality and consumption, including a study on fluoridated water [

23], and two studies that included the impact of taste and demographics on perceptions of water [

24,

25]. These studies address consumption, but are related more to water quality than to scarcity issues. In this research, individuals’ perceptions of water quantity were addressed.

The rationale for the study is to address the current literature gap between individuals’ perceptions of water and perceptions of the value of water, water consumption, water regulations, the water footprint, and water scarcity, and further our knowledge regarding people’s perceptions of water and our understanding about the different ways individuals use water. This is important in order to better understand the views of the public, the actions the public considers as necessary, and how the public would like to have water issues addressed, including elements such as who is seen to be the appropriate regulating body. Such knowledge will provide a foundation for further research and help to guide policy. Syme and Williams and, more recently, Hu

et al. concluded that perceptions of water influence the actions of individuals, particularly in regards to perceptions of water quality and consumption of bottled water [

3,

15]. Similar to an older study by Doria

et al. [

26], Hu

et al. suggest that when trying to understand people’s behaviour concerning water use, it is useful to first understand how people perceive their water [

3]. This study aims to discover how people perceive water and how it relates to their use of water.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics of the Sample

The final population of our study included 164 participants of that 75% completed the survey. Of the participants, 108 identified as being male and 49 identified as female; 45 indicated being under 18 years of age, 90 indicated being between 18 and 24 years old, 15 between 25 and 39 years old, and nine over 39 years old. Of the participants, 74 indicated that they currently live in Canada, 65 from the United States of America, and one from each of the following countries: Taiwan, France, Austria, UK, Norway, Finland, and Italy. This variety of participants offered a wide collection of responses, opinions and ideas, however the large majority of the participants were from younger age groups in Canada and the US. Based on the qualitative comments of participants the authors posit that the participants were from areas that are typically water abundant, for example, “seeing those who do not have instant access to clean water from a tap makes me feel instant gratitude for my access to clean water” and “For those of us who have unlimited access to water…”. The authors submit that a question around water climate in the area the research participant resides would add to better understand recipients’ answers on scarcity. This may be considered a limitation, as there may be little insight from participants residing in water scarce regions.

As well, there is potential bias within the results based on the respondents, as well as the non-response rate. Furthermore, over-reporting on good behaviour may also be a cause of bias in the results. The authors acknowledge these possible biases, and believe the results still offer insight to the research question.

3.2. Themes

The comment boxes provided participants with a chance to expand on their answers to the quantitative questions and offer further insight. The codes found in the comments revealed common themes: Education needed (n = 35), Free water (n = 20), Bottled water (n = 16), Government (n = 16), Conserving behaviour (n = 15) and Responsibility (n = 15), Accessibility (n = 11), Human right (n = 11), Life (n = 11), Knowledge gained (n = 9), Mitigate consumption (n = 9), Non-monetary cost (n = 9), Availability (n = 8), Affordability (n = 7), Monetary cost (n = 6), Increase the price of water (n = 5), First Nations (n = 2), Government control (n = 2), and Indirect use (n = 1). Over 430 comments provided a wealth of information, including more detailed answers to the question, questions about the question, and comments about the question.

3.2.1. Theme: Responsibility

Responsibility was discussed frequently in the comments, both in response to the questions about responsibility and in other contexts. The majority of respondents believed that it is the responsibility of the government to ensure access to clean water (78.6% = Local government and 71.4% = Federal government) and very few respondents thought that it is at all the responsibility of the individual (20.0%) (

Table 1). Many reacted to the question “Would you be in favour of putting restrictions on the amount of water an entire community is allowed to use on a daily basis?” by commenting that if there was a restriction on an entire community, individuals would act selfishly. For example, one participant responded “Only if house to house was also restricted, otherwise one house would obey the restrictions while another used the entire amount”. A fear of individuals acting solely for their own best interest resonated with the majority of the participants indicating that the government should be in charge.

Table 1.

Beliefs about responsibility for providing clean water: All participants.

Table 1.

Beliefs about responsibility for providing clean water: All participants.

| Responsible entity | Response rate (%) |

|---|

| The local government | 78.6 |

| The federal government | 71.4 |

| Non-governmental organizations | 15.7 |

| Trans/International bodies | 26.4 |

| It is the responsibility of the individual | 20.0 |

Scarcity was discussed in relation to the need for conservation and restrictions, and the general consensus is that water restrictions are only necessary in water scarce areas. Comments included: “In areas where water is less abundant, for example the Vegas area, restrictions should exist”, “I avoid beef as much as I can, particularly if it is produced in water poor regions”, and water should be “Free if abundant”. The sentiment of the respondents who were opposed to restrictions (48.61%) (based on responses to a Likert scale question) may be related to the lack of concern for running out of water in the participant’s community (61.4%) (

Table 2). Yet, while nearly half of the participants were opposed to restrictions, conservation efforts were still apparent: the majority of participants acknowledged making an effort to conserve water (54.75%).

Table 2.

Beliefs about water scarcity: All participants.

Table 2.

Beliefs about water scarcity: All participants.

| Level of concern | Response rate (%) |

|---|

| Yes, very concerned | 6.3 |

| No, not in this life time | 61.4 |

| Maybe, but not for a long time | 25.2 |

| Not sure | 7.1 |

3.2.2. Theme: The Value of Water

There were a wide variety of comments regarding the value of water. Many respondents commented that the value of water is best seen in non-monetary ways. In response to the question “The greatest way to appreciate the value of water is to… (a) Look at the price of a bottle of water in a convenience store; (b) Look at a waterfall; (c) Compare the condition of those who have clean water to those who do not have clean water; (d) Water does not have a value; (e) Other (

Table 3), no respondents indicated that the true value of water is reflected in the price of a bottle of water, and only one respondent commented that the value of water is reflected in the cost of obtaining it. Based on the results, the value of water is most commonly seen by comparing those who have clean water to those who do not (80.7%). This is reflected in the comments: four respondents commented that the value of water is truly appreciated when one becomes thirsty.

Table 3.

Beliefs about the value of water: All participants.

Table 3.

Beliefs about the value of water: All participants.

| Ways to value water | Response rate (%) |

|---|

| Compare the condition of those who have clean water to those who do not have clean water | 80.7 |

| Other | 8.6 |

| Water does not have a value | 6.4 |

| Look at a waterfall | 4.3 |

| Look at the price of a bottle of water in a convenience store | 0 |

On the other hand, the monetary value of water is also mentioned: “I would say the value of water is how much the average person would pay for water in an area i.e., the average water bill/ how many people purify their own water”. Comments such as “Just raise water rates” were found five times throughout the survey. This indicates that some participants thought that raising the price of water will encourage conservation. However, although some participants acknowledge the use of raising the price of water in order to promote water conservation, the majority indicated they were opposed to charging more money for water. This opposition is reflected in the question “Which do you prefer, a tax or a reimbursement?” in which the respondents had to choose between the two; 84.3% preferred a reimbursement, (n = 4) commented “neither”, and 43 respondents skipped the question. This illustrates opposition to paying more for water.

Yet when asked “Would you be willing to pay an additional amount on your monthly bill in order to ensure a sustained supply of water for yourself?” 37.1% of respondents indicated they would be willing to pay to guarantee a sustained supply of water (32.8% were Unsure and 30.2% said No). And when asked about putting a price on guaranteeing a sustained water supply (“Regardless of whether you are currently paying for your water, how much would you be willing to pay out of a pocket monthly in order to ensure a sustained supply of water for your household?”), 87.1% indicated they would be willing to pay some amount more than CAD$1.00 (

Table 4). This appears contradictory, as 30.2% of respondents indicated they would not be willing to pay an additional fee on a monthly bill, yet only 12.9% indicated “None” when asked how much they would be willing to pay.

Table 4.

Beliefs about payment for a guaranteed water supply: All participants.

Table 4.

Beliefs about payment for a guaranteed water supply: All participants.

| Amount individual is willing to pay | Response rate (%) |

|---|

| As much as is necessary to maintain a secure water supply | 37.9 |

| Between CAD $1.00–5.00 | 28.4 |

| Between CAD $5.01–7.50 | 20.7 |

| None | 12.9 |

3.2.3. Theme: Knowledge Gained

Several comments indicated that knowledge was gained during participation in the survey. One participant commented that “After completing this survey, I would try to make an effort to cut back regardless of a reimbursement”. In response to reading that it takes 15,400 L of water to produce one kilogram of beef [

20], a participant commented “I had no idea, that is unreal”. In response to the question of whether to add a water footprint label on consumer goods a participant commented “This is a really good idea.” Based on the comments, it seems that participants learned more about water issues.

3.2.4. Theme: Education Needed

However, a lack of knowledge on many water related issues also became apparent. Comments indicated that education is needed in the following areas: (1) water conservation actions, e.g., “How does the container you drink your water from have anything to do with water conservation?” (2) water recycling technology, e.g., “would toilet water be reused after flushing? you need a hell of a purification system for that.” and “Does it smell bad?” and most prominently; (3) awareness of the water consumption rates and the possibility of water scarcity, e.g., in response to a question regarding adding the water footprint label to consumer goods “Need to get the idea out there that this is important first before it will be beneficial putting them on consumer goods” and “I am not sure if it would influence the general public until more awareness is raised”. Another example of awareness issues became apparent in the responses to the question “Given what you know about water consumption, how many litres of water would you estimate you use in one day?” in which there were twelve comments akin to “I really have no idea”. Only 10.8% of the participants indicated they think they use over 100 L of water a day. The majority (50.8%) indicated that they think that they use between 20 and 50 L of water a day (

Table 5). In reality, the average Canadian uses 329 L of water a day [

40]. One respondent admitted: “Without knowing more about my current consumption level, I cannot judge what cutting back 10 litres would require”. Also related to consumption are the indirect uses of water, which many seemed to be unaware of: “Again, maybe I just don’t know the relation between eating beef and eating meat is to water consumption, but I don’t see the relevance”. These comments indicate that there is a lack of knowledge on water conservation, water reuse, and water consumption rates.

Table 5.

Beliefs about personal daily water consumption (in liters): All participants.

Table 5.

Beliefs about personal daily water consumption (in liters): All participants.

| Believed water daily consumption in litres | Response rate (%) |

|---|

| 20–50 | 50.8 |

| 50–100 | 22.5 |

| 10–20 | 15.8 |

| 100 or more | 10.8 |

3.3. Perceptions of Water versus Beliefs and Actions

The final results were cross tabulated using Survey Monkey data analysis tools, filtering for demographics, including gender, current country of residence and age, and for each perception of water (commodity, human right, private resource, public resource, natural resource).

As all participants did not answer all the questions, data is presented as percentages. The individual’s perception of water was addressed in the first question, in which the participant could select more than one response; all of the answers were chosen by at least fifteen participants. A natural resource was selected by 67.9% of the participants, a human right by 51.4%, a public resource by 40.7%, a commodity by 30.0%, and a private resource by 10.7% (

Table 6). We addressed how these perceptions are related to beliefs about the price of water, about whose responsibility it is to provide access to clean water, about the importance of conservation, and about personal consumption habits, in order to better understand the non-statistical association between perceptions and beliefs and actions.

Table 6.

Perceptions of water: All participants.

Table 6.

Perceptions of water: All participants.

| Water is seen as… | Response rate (%) |

|---|

| A natural resource | 67.9 |

| A human right | 51.4 |

| A public resource | 40.7 |

| A commodity | 30.0 |

| A private resource | 10.7 |

Several beliefs were found to be similar throughout the different perceptions. First was the sentiment that the government, both local and federal, should be in charge of ensuring the public has access to clean water. The only exception to this belief was within those who indicated that water is a private resource, where 86.7% thought it was the responsibility of the local government, but only 46.7% thought it was the responsibility of the federal government. Thus, in the case of those who perceived water to be a private resource it was still seen as the government’s responsibility, but specifically the local government. Furthermore, when asked “How much of an effort do you put into conserving water” on a scale of one to seven, seven being “I always make an effort”, the average among the different perceptions was between 4.00 and 4.44. As well, there was no difference in the water conserving behaviours between the groups; in all groups the majority take short showers and do only full loads of laundry.

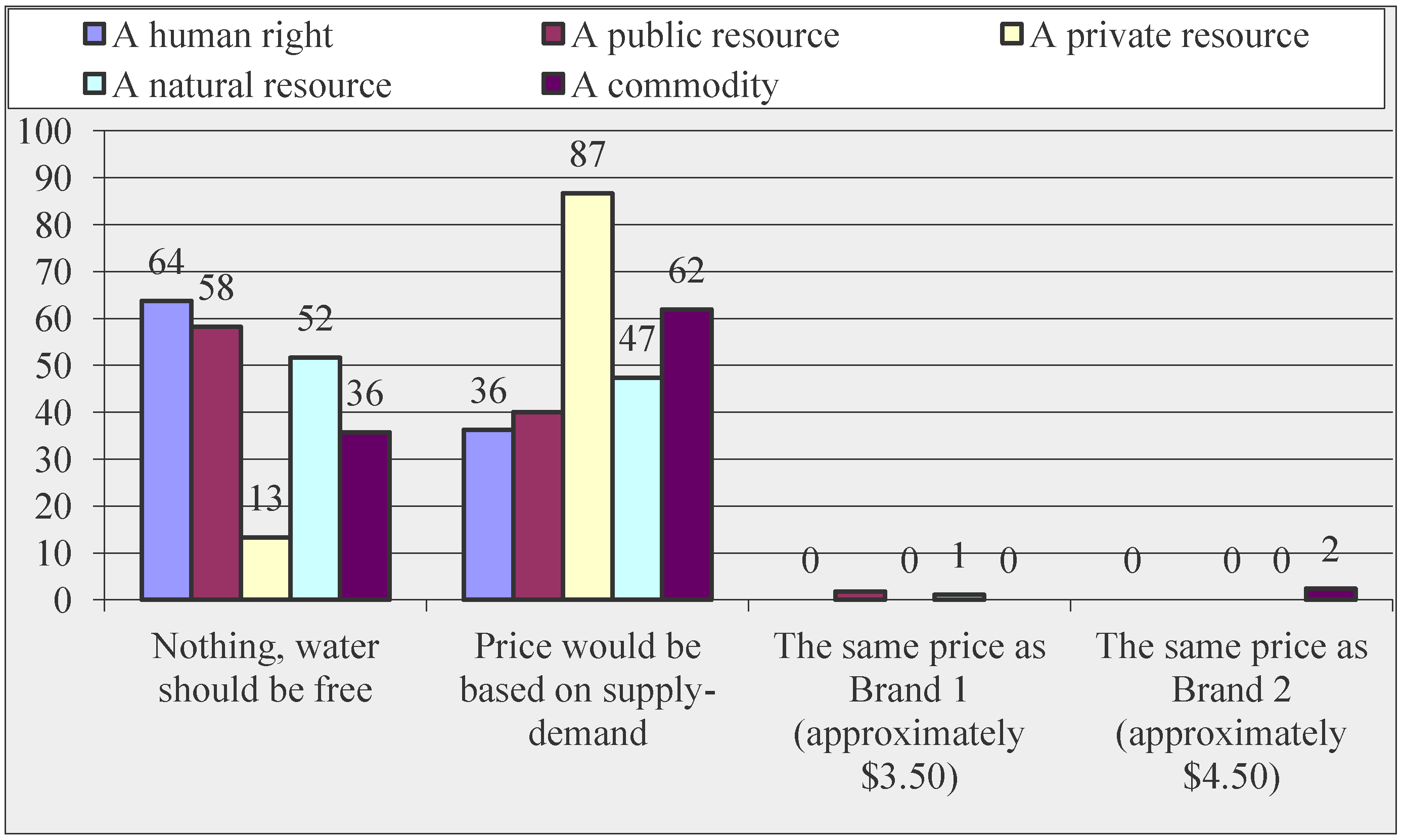

The difference amongst the perceptions was found in beliefs about the cost of water (

Figure 1). From highest to lowest number of participants who thought water should be free: #1. participants who perceived clean drinking water to be a human right (63.8%); #2. participants who perceived clean drinking water to be a commodity (61.9%); #3. participants who perceived clean drinking water to be a public resource (58.2%); #4. participants who perceived clean drinking water to be a natural resource (51.6%); and #5. participants who perceived clean drinking water to be a private resource (13.3%).

Figure 1.

Comparison of beliefs about the cost of water. If water was to be sold on a drop-by-drop basis, how much would you charge for one litre? (%)

Figure 1.

Comparison of beliefs about the cost of water. If water was to be sold on a drop-by-drop basis, how much would you charge for one litre? (%)

The beliefs of those who perceive water to be a private resource are particularly unique. Those believed water is a private resource felt differently about the importance of conserving water: when asked how important it is to conserve water on a Likert scale of one to seven, seven being “very important”, all the other participants indicated an average between 5.68 and 5.97 while the average response of those who perceived water as a private resource was 4.85 (

Table 7). More respondents (86.7%) think water should have a price based on supply and demand than those who think water should be free (13.3%). Of those who perceive water to be a private resource, 27% believe it is the responsibility of the individual to ensure access to clean water, which is the largest portion compared to the beliefs of the other perceptions.

Table 7.

Comparison of beliefs about the importance of conserving water.

Table 7.

Comparison of beliefs about the importance of conserving water.

| Those who believe water is primarily… | Importance of conserving water (1–7) |

|---|

| A public resource | 5.98 |

| A human right | 5.97 |

| A natural resource | 5.87 |

| A commodity | 5.68 |

| A private resource | 4.85 |