How Do Gangliosides Regulate RTKs Signaling?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

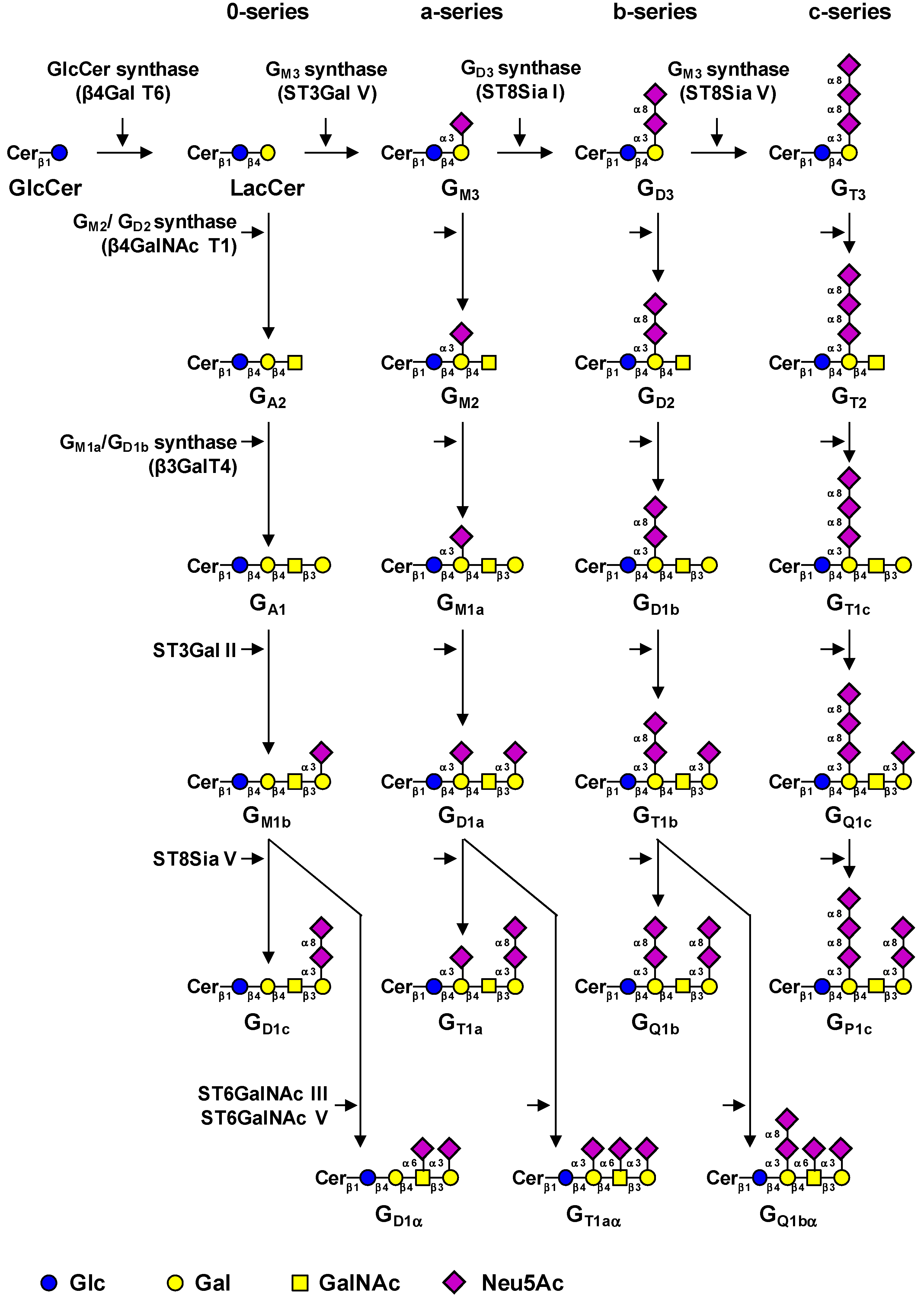

2. Biosynthesis of Gangliosides

| Gene | Common name | Main acceptors | Accession # | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UGCG | GlcCer synthase | Ceramide | NM_003358 | (12) |

| B4GALT6 | LacCer synthase | Glucosylceramide | NM_004775 | (13, 14) |

| ST3GAL5 | GM3 synthase | Lactosylceramide | NM_003896 | (16) |

| ST8SIA1 | GD3 synthase | GM3, GD3 | NM_003034.2 | (18) |

| ST8SIA5 | GT3 synthase | GD3, GM1b, GD1a, GT1b | NM_013305 | (21) |

| B4GALNACT1 | GM2/GD2 synthase | GA3, GM3, GD3, GT3 | NM_001478.2 | (22) |

| B3GALT4 | GM1a/GD1b synthase | GA2, GM2, GD2, GT2 | NM_003782.3 | (23) |

| ST3GAL2 | ST3Gal II | Galβ1-3GalNAc-R | NM_006927 | (26, 27) |

| ST6GALNAC3 | ST6GalNAc III | Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-3GalNAc-R | NM_152996 | (28) |

| ST6GALNAC5 | ST6GalNAc V | Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-3GalNAc-R | NM_030965.1 | (29) |

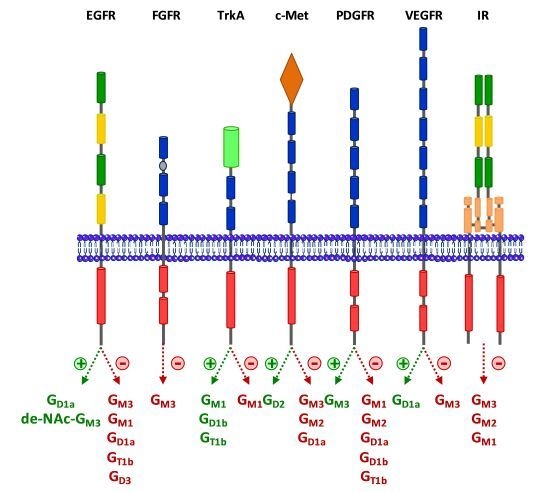

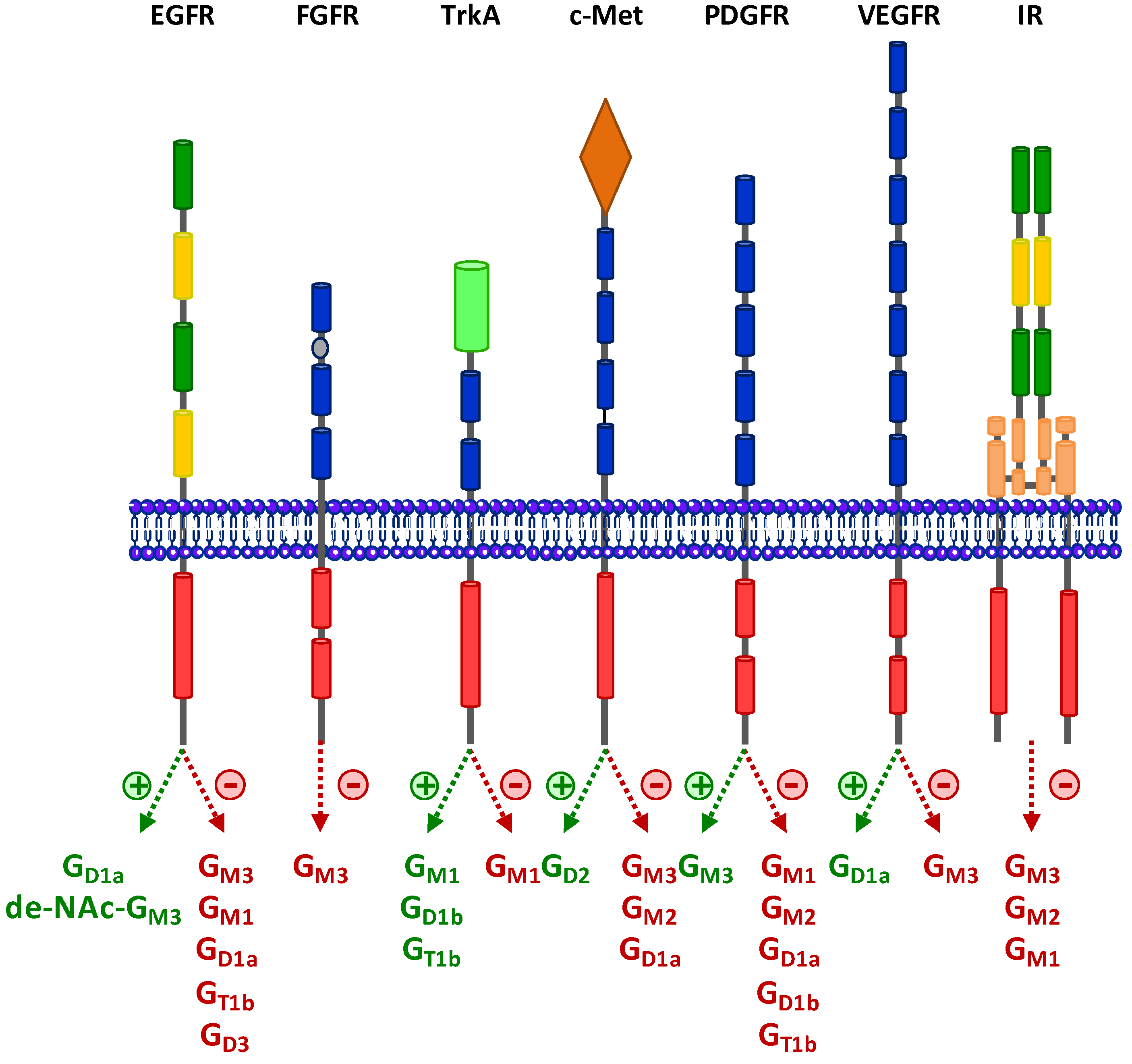

3. Regulation of RTKs Signaling by Gangliosides

3.1. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR)

3.2. Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor (FGFR)

3.3. Neurotrophins Receptors

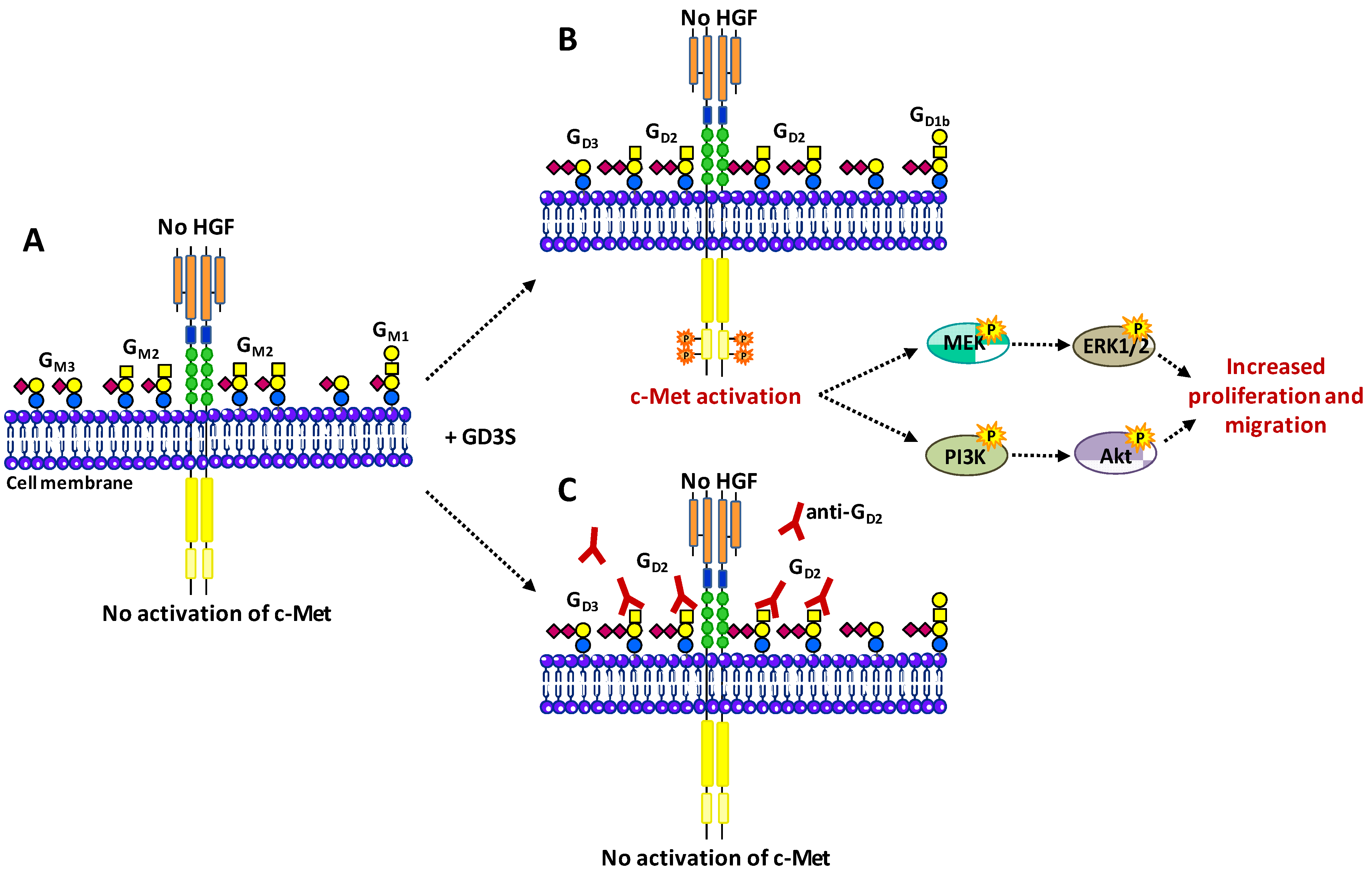

3.4. Hepatocyte Growth Factor Receptor c-Met

3.5. Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor (PDGFR)

3.6. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor (VEGFR)

3.7. Insulin Receptor

4. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Svennerholm, L. Ganglioside designation. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1980, 125, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, T.; Wada, R.; Sasaki, T.; Deng, C.; Bierfreund, U.; Sandhoff, K.; Proia, R.L. A vital role for glycosphingolipid synthesis during development and differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999, 96, 9142–9147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakomori, S.I. The glycosynapse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002, 99, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regina, T.A.; Hakomori, S.I. Functional role of glycosphingolipids and gangliosides in control of cell adhesion, motility, and growth, through glycosynaptic microdomains. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008, 1780, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariga, T.; McDonald, M.P.; Yu, R.K. Role of ganglioside metabolism in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease--a review. J. Lipid Res. 2008, 49, 1157–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrizaila, N.; Yuki, N. Guillain-Barré syndrome animal model: the first proof of molecular mimicry in human autoimmune disorder. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2011, 2011, 829129. [Google Scholar]

- Miljan, E.A.; Bremer, E.G. Regulation of growth factor receptors by gangliosides. Sci. STKE. 2002, 2002, re15. [Google Scholar]

- Ohmi, Y.; Tajima, O.; Ohkawa, Y.; Mori, A.; Sugiura, Y.; Furukawa, K.; Furukawa, K. Gangliosides play pivotal roles in the regulation of complement systems and in the maintenance of integrity in nerve tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009, 106, 22405–22410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birklé, S.; Zeng, G.; Gao, L.; Yu, R.K.; Aubry, J. Role of tumor-associated gangliosides in cancer progression. Biochimie. 2003, 85, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobowski, M.; Cazet, A.; Steenackers, A.; Delannoy, P. Role of complex gangliosides in cancer progression. Carbohydr. Chem. 2012, 37, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, A.S.; Hancock, J.F. Using plasma membrane nanoclusters to build better signaling circuits. Trends Cell Biol. 2008, 18, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichikawa, S.; Sakiyama, H.; Suzuki, G.; Hidari, K.I.; Hirabayashi, Y. Expression cloning of a cDNA for human ceramide glucosyltransferase that catalyzes the first glycosylation step of glycosphingolipid synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996, 93, 4638–4643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, T.; Takizawa, M.; Aoki, J.; Arai, H.; Inoue, K.; Wakisaka, E.; Yoshizuka, N.; Imokawa, G.; Dohmae, N.; Takio, K.; et al. Purification, cDNA cloning, and expression of UDP-Gal: glucosylceramide beta-1,4-galactosyltransferase from rat brain. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 13570–13577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takizawa, M.; Nomura, T.; Wakisaka, E.; Yoshizuka, N.; Aoki, J.; Arai, H.; Inoue, K.; Hattori, M.; Matsuo, N. cDNA cloning and expression of human lactosylceramide synthase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999, 1438, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.; Yu, R.K. Cloning and transcriptional regulation of genes responsible for synthesis of gangliosides. Curr. Drug Targets. 2008, 9, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, A.; Ohta, M.; Watanabe, Y.; Matsuda, K.; Ishiyama, K.; Sakoe, K.; Nakamura, M.; Inokuchi, J.; Sanai, Y.; Saito, M. Expression cloning and functional characterization of human cDNA for ganglioside GM3 synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 31652–31655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, M.A.; Cross, H.; Proukakis, C.; Priestman, D.A.; Neville, D.C.; Reinkensmeier, G.; Wang, H.; Wiznitzer, M.; Gurtz, K.; Verganelaki, A.; et al. Infantile-onset symptomatic epilepsy syndrome caused by a homozygous loss-of-function mutation of GM3 synthase. Nat. Genet. 2004, 36, 1225–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraguchi, M.; Yamashiro, S.; Yamamoto, A.; Furukawa, K.; Takamiya, K.; Lloyd, K.O.; Shiku, H.; Furukawa, K. Isolation of GD3 synthase gene by expression cloning of GM3 alpha-2,8-sialyltransferase cDNA using anti-GD2 monoclonal antibody. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994, 91, 10455–10459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, J.; Fukuda, M.N.; Hirabayashi, Y.; Kanamori, A.; Sasaki, K.; Nishi, T.; Fukuda, M. Expression cloning of a human GT3 synthase. GD3 and GT3 are synthesized by a single enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 3684–3691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenackers, A.; Vanbeselaere, J.; Cazet, A.; Bobowski, M.; Rombouts, Y.; Colomb, F.; Le Bourhis, X.; Guérardel, Y.; Delannoy, P. Accumulation of unusual gangliosides G(Q3) and G(P3) in breast cancer cells expressing the G(D3) synthase. Molecules. 2012, 17, 9559–9572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kim, K.S.; Do, S.; Kim, C.H.; Kim, S.K.; Lee, Y.C. Molecular cloning and expression of human alpha2,8-sialyltransferase (hST8Sia V). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997, 235, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, Y.; Yamashiro, S.; Yodoi, J.; Lloyd, K.O.; Shiku, H.; Furukawa, K. Expression cloning of beta 1,4 N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase cDNAs that determine the expression of GM2 and GD2 gangliosides. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 12082–12089. [Google Scholar]

- Amado, M.; Almeida, R.; Carneiro, F.; Levery, S.B.; Holmes, E.H.; Nomoto, M.; Hollingsworth, M.A.; Hassan, H.; Schwientek, T.; Nielsen, P.A.; et al. A family of human beta3-galactosyltransferases. Characterization of four members of a UDP-galactose: beta-N-acetyl-glucosamine/beta-N-acetyl-galactosamine beta-1,3-galactosyltransferase family. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 12770–12778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iber, H.; Zacharias, C.; Sandhoff, K. The c-series gangliosides GT3, GT2 and GP1c are formed in rat liver Golgi by the same set of glycosyltransferases that catalyse the biosynthesis of asialo-, a- and b-series gangliosides. Glycobiology. 1992, 2, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashiro, S.; Haraguchi, M.; Furukawa, K.; Takamiya, K.; Yamamoto, A.; Nagata, Y.; Lloyd, K.O.; Shiku, H.; Furukawa, K. Substrate specificity of beta 1,4-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase in vitro and in cDNA-transfected cells. GM2/GD2 synthase efficiently generates asialo-GM2 in certain cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 6149–6155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordanengo, V.; Bannwarth, S.; Laffont, C.; Van Miegem, V.; Harduin-Lepers, A.; Delannoy, P.; Lefebvre, J.C. Cloning and expression of cDNA for a human Gal(beta1–3)GalNAc alpha2,3-sialyltransferase from the CEM T-cell line. Eur. J. Biochem. 1997, 247, 558–566. [Google Scholar]

- Sturgill, E.R.; Aoki, K.; Lopez, P.H.; Colacurcio, D.; Vajn, K.; Lorenzini, I.; Majić, S.; Yang, W.H.; Heffer, M.; Tiemeyer, M.; et al. Biosynthesis of the major brain gangliosides GD1a and GT1b. Glycobiology. 2012, 22, 1289–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchida, A.; Ogiso, M.; Nakamura, Y.; Kiso, M.; Furukawa, K.; Furukawa, K. Molecular cloning and expression of human ST6GalNAc III: restricted tissue distribution and substrate specificity. J. Biochem. 2005, 138, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okajima, T.; Fukumoto, S.; Ito, H.; Kiso, M.; Hirabayashi, Y.; Urano, T.; Furukawa, K. Molecular cloning of brain-specific GD1alpha synthase (ST6GalNAc V) containing CAG/Glutamine repeats. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 30557–30562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccioni, H.J.; Daniotti, J.L.; Martina, J.A. Organization of ganglioside synthesis in the Golgi apparatus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999, 1437, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nairn, A.V.; York, W.S.; Harris, K.; Hall, E.M.; Pierce, J.M.; Moremen, K.W. Regulation of gly-can structures in animal tissues: transcript profiling of glycan-related genes. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 17298–17313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidari, J.K.; Ichikawa, S.; Furukawa, K.; Yamasaki, M.; Hirabayashi, Y. beta 1-4N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase can synthesize both asialoglycosphingolipid GM2 and glycosphingolipid GM2 in vitro and in vivo: Isolation and characterization of a beta 1-4N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase cDNA clone from rat ascites hepatoma cell line AH7974F. Biochem. J. 1994, 303, 957–965. [Google Scholar]

- Fukumoto, S.; Miyazaki, H.; Goto, G.; Urano, T.; Furukawa, K.; Furukawa, K. Expression cloning of mouse cDNA of CMP-NeuAc: Lactosylceramide alpha2,3-sialyltransferase, an enzyme that imitates the synthesis of gangliosides. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 9271–9276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Preuss, U.; Gu, T.; Yu, R.K. Regulation of sialyltransferase activities by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. J. Neurochem. 1995, 64, 2295–2302. [Google Scholar]

- Bieberich, E.; Freischütz, B.; Liour, S.S.; Yu, R.K. Regulation of ganglioside metabolism by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. J. Neurochem. 1998, 71, 972–979. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, R.K.; Bieberich, E. Regulation of glycosyltransferases in ganglioside biosynthesis by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2001, 177, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmon, M.A.; Schlessinger, J. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell 2010, 141, 1117–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremer, E.G.; Schlessinger, J.; Hakomori, S. Ganglioside-mediated modulation of cell growth. Specific effects of GM3 on tyrosine phosphorylation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1986, 261, 2434–2440. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Shao, H.; Cox, N.R.; Baker, H.J.; Ewald, S.J. Gangliosides enhance apoptosis of thymocytes. Cell. Immunol. 1998, 183, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremer, E.G.; Hakomori, S.I. Gangliosides as receptor modulators. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1984, 174, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakomori, S.; Igarashi, Y. Functional role of glycosphingolipids in cell recognition and signaling. J. Biochem. 1995, 118, 1091–1103. [Google Scholar]

- Kaucic, K.; Liu, Y.; Ladisch, S. Modulation of growth factor signaling by gangliosides: positive or negative? Methods Enzymol. 2006, 417, 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, A.Z.; Abella, J.V.; Park, M. Crosstalk in Met receptor oncogenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 2009, 19, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Yoon, S.J.; Freire-de-Lima, L.; Kim, J.H.; Hakomori, S.I. Control of cell motility by interaction of gangliosides, tetraspanins, and epidermal growth factor receptor in A431 versus KB epidermoid tumor cells. Carbohydr. Res. 2009, 344, 1479–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todeschini, A.R.; Dos Santos, J.N.; Handa, K.; Hakomori, S.I. Ganglioside GM2-tetraspanin CD82 complex inhibits met and its cross-talk with integrins, providing a basis for control of cell motility through glycosynapse. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 8123–8133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebbaa, A.; Hurh, J.; Yamamoto, H.; Kersey, D.S.; Bremer, E.G. Ganglioside GM3 inhibition of EGF receptor mediated signal transduction. Glycobiology. 1996, 6, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanai, N.; Dohi, T.; Nores, G.A.; Hakomori, S. A novel ganglioside, de-N-acetyl-GM3 (II3NeuNH2LacCer), acting as a strong promoter for epidermal growth factor receptor kinase and as a stimulator for cell growth. J. Biol. Chem. 1988, 263, 6296–6301. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q.; Hakomori, S.; Kitamura, K.; Igarashi, Y. GM3 directly inhibits tyrosine phosphorylation and de-N-acetyl-GM3 directly enhances serine phosphorylation of epidermal growth factor receptor, independently of receptor-receptor interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 1959–1965. [Google Scholar]

- Meuillet, E.J.; Mania-Farnell, B.; George, D.; Inokuchi, J.I.; Bremer, E.G. Modulation of EGF receptor activity by changes in the GM3 content in a human epidermoid carcinoma cell line, A431. Exp. Cell Res. 2000, 256, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miljan, E.A.; Meuillet, E.J.; Mania-Farnell, B.; George, D.; Yamamoto, H.; Simon, H.G.; Bremer, E.G. Interaction of the extracellular domain of the epidermal growth factor receptor with gangliosides. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 10108–10113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.J.; Nakayama, K.; Hikita, T.; Handa, K.; Hakomori, S.I. Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase is modulated by GM3 interaction with N-linked GlcNAc termini of the receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006, 103, 18987–18991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, N.; Yoon, S.J.; Itoh, K.; Nakayama, K. Tyrosine kinase activity of epidermal growth factor receptor is regulated by GM3 binding through carbohydrate to carbohydrate interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 6147–6155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, F.; Handa, K.; Hakomori, S.I. Regulation of epidermal growth factor receptor through interaction of ganglioside GM3 with GlcNAc of N-linked glycan of the receptor: demonstration in ldlD cells. Neurochem. Res. 2011, 36, 1645–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Ma, K. Ganglioside GM3 inhibits hepatoma cell motility via down-regulating activity of EGFR and PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. J. Cell. Biochem. 2013, 114, 1616–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Ma, K. Synergistic inhibition of cell migration by tetraspanin CD82 and gangliosides occurs via the EGFR or cMet-activated Pl3K/Akt signalling pathway. Int. J. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 2013, 45, 2349–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coskun, Ü.; Grzybek, M.; Drechsel, D.; Simons, K. Regulation of human EGF receptor by lipids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011, 108, 9044–9048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurita, A.R.; Maccioni, H.J.; Daniotti, J.L. Modulation of epidermal growth factor receptor phosphorylation by endogenously expressed gangliosides. Biochem. J. 2001, 355, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirkin, B.L.; Clark, S.H.; Zhang, C. Inhibition of human neuroblastoma cell proliferation and EGF receptor phosphorylation by gangliosides GM1, GM3, GD1A and GT1B. Cell Prolif. 2002, 35, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, R.; Ladisch, S. Exogenous ganglioside GD1a enhances epidermal growth factor receptor binding and dimerization. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 36481–36489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.J.; Jung, K.Y.; Kwak, D.H.; Lee, S.H.; Ryu, J.S.; Kim, J.S.; Chang, K.T.; Lee, J.W.; Choo, Y.K. Inhibition of ganglioside GD1a synthesis suppresses the differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells into osteoblasts. Dev. Growth Differ. 2011, 53, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudò, G.; Bonomo, A.; Di Liberto, V.; Frinchi, M.; Fuxe, K.; Belluardo, N. The FGF-2/FGFRs neurotrophic system promotes neurogenesis in the adult brain. J. Neural Transm. 2009, 116, 995–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuillet, E.; Cremel, G.; Dreyfus, H.; Hicks, D. Differential modulation of basic fibroblast and epidermal growth factor receptor activation by ganglioside GM3 in cultured retinal Müller glia. Glia. 1996, 17, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, M.S.; Suzuki, E.; Handa, K.; Hakomori, S. Cell growth regulation through GM3-enriched microdomain (glycosynapse) in human lung embryonal fibroblast WI38 and its oncogenic transformant VA13. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 34655–34664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, M.S.; Suzuki, E.; Handa, K.; Hakomori, S. Effect of ganglioside and tetraspanins in microdomains on interaction of integrins with fibroblast growth factor receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 16227–16234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutoh, T.; Tokuda, A.; Miyadai, T.; Hamaguchi, M.; Fujiki, N. Ganglioside GM1 binds to the Trk protein and regulates receptor function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995, 92, 5087–5091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabin, S.J.; Mocchetti, I. GM1 ganglioside activates the high affinity nerve growth factor receptor trkA. J. Neurochem. 1995, 65, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchemin, A.M.; Ren, Q.; Mo, L.; Neff, N.H.; Hajiconstantinou, M. GM1 ganglioside induces phosphorylation and activation of Trk and Erk in brain. J. Neurochem. 2002, 81, 696–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishio, M.; Fukumoto, S.; Furukawa, K.; Ichimura, A.; Miyazaki, H.; Kusunoki, S.; Urano, T.; Furukawa, K. Overexpressed GM1 suppresses nerve growth factor (NGF) signals by modulating the intracellular localization of NGF receptors and membrane fluidity in PC12 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 33368–33378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumoto, S.; Mutoh, T.; Hasegawa, T.; Miyazaki, H.; Okada, M.; Goto, G.; Furukawa, K.; Urano, T. GD3 synthase gene expression in PC12 cells results in the continuous activation of TrkA and ERK1/2 and enhanced proliferation. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 5832–5838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchemin, A.M.; Ren, Q.; Neff, N.H.; Hadjiconstantinou, M. GM1-induced activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase: Involvement of Trk receptors. J. Neurochem. 2008, 104, 1466–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todeschini, A.R.; Dos Santos, J.N.; Handa, K.; Hakomori, S.I. Ganglioside GM2/GM3 complex affixed on silica nanospheres strongly inhibits cell motility through CD82/cMet-mediated pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008, 105, 1925–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazet, A.; Lefebvre, J.; Adriaenssens, E.; Julien, S.; Bobowski, M.; Grigoriadis, A.; Tutt, A.; Tulasne, D.; Le Bourhis, X.; Delannoy, P. GD3 synthase expression enhances proliferation and tumor growth of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells through c-Met activation. Mol. Cancer Res. 2010, 8, 1526–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazet, A.; Groux-Degroote, S.; Teylaert, B.; Kwon, K.M.; Lehoux, S.; Slomianny, C.; Kim, C.H.; Le Bourhis, X.; Delannoy, P. GD3 synthase overexpression enhances proliferation and migration of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Biol. Chem. 2009, 390, 601–609. [Google Scholar]

- Cazet, A.; Bobowski, M.; Rombouts, Y.; Lefebvre, J.; Steenackers, A.; Popa, I.; Guérardel, Y.; Le Bourhis, X.; Tulasne, D.; Delannoy, P. The ganglioside G(D2) induces the constitutive activation of c-Met in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells expressing the G(D3) synthase. Glycobiology 2012, 22, 806–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyuga, S.; Kawasaki, N.; Hyuga, M.; Ohta, M.; Shibayama, R.; Kawanishi, T.; Yamagata, S.; Yamagata, T.; Hayakawa, T. Ganglioside GD1a inhibits HGF-induced motility and scattering of cancer cells through suppression of tyrosine phosphorylation of c-Met. Int. J. Cancer. 2001, 94, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremer, E.G.; Hakomori, S.; Bowen-Pope, D.F.; Raines, E.; Ross, R. Ganglioside-mediated modulation of cell growth, growth factor binding, and receptor phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 1984, 259, 6818–6825. [Google Scholar]

- Yates, A.J.; Saqr, H.E.; Van Brocklyn, J. Ganglioside modulation of the PDGF receptor. A model for ganglioside functions. J. Neurooncol. 1995, 24, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynds, D.L.; Summers, M.; Van Brocklyn, J.; O'Dorisio, M.S.; Yates, A.J. Gangliosides inhibit platelet-derived growth factor-stimulated growth, receptor phosphorylation, and dimerization in neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. J. Neurochem. 1995, 65, 2251–2258. [Google Scholar]

- Van Brocklyn, J.; Bremer, E.G.; Yates, A.J. Gangliosides inhibit platelet-derived growth factor-stimulated receptor dimerization in human glioma U-1242MG and Swiss 3T3 cells. J. Neurochem. 1993, 61, 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golard, A. Anti-GM3 antibodies activate calcium inflow and inhibit platelet-derived growth factor beta receptors (PDGFbetar) in T51B rat liver epithelial cells. Glycobiology 1998, 8, 1221–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooqui, T.; Kelley, T.; Coggeshall, K.M.; Rampersaud, A.A.; Yates, A.J. GM1 inhibits early signaling events mediated by PDGF receptor in cultured human glioma cells. Anticancer Res. 1999, 19, 5007–5013. [Google Scholar]

- Oblinger, J.L.; Boardman, C.L.; Yates, A.J.; Burry, R.W. Domain-dependent modulation of PDGFRbeta by ganglioside GM1. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2003, 20, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsuda, T.; Furukawa, K.; Fukumoto, S.; Miyazaki, H.; Urano, T.; Furukawa, K. Overexpression of ganglioside GM1 results in the dispersion of platelet-derived growth factor receptor from glycolipid-enriched microdomains and in the suppression of cell growth signals. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 11239–11246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brdicka, T.; Pavlistova, D.; Leo, A.; Bruyns, E.; Korinek, V.; Angelisova, P.; Scherer, J.; Shevchenko, A.; Hilgert, I.; Cerný, J.; et al. Phosphoprotein associated with glycosphingolipid-enriched microdomains (PAG), a novel ubiquitously expressed transmembrane adaptor protein, binds the protein tyrosine kinase csk and is involved in regulation of T cell activation. J. Exp. Med. 2000, 191, 1591–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veracini, L.; Simon, V.; Richard, V.; Schraven, B.; Horejsi, V.; Roche, S.; Benistant, C. The Csk-binding protein PAG regulates PDGF-induced Src mitogenic signaling via GM1. J. Cell Biol. 2008, 182, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; McCarthy, J.; Ladisch, S. Membrane ganglioside enrichment lowers the threshold for vascular endothelial cell angiogenic signaling. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 10408–10414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, Z.; Guerrera, M.; Li, R.; Ladisch, S. Ganglioside GD1a enhances VEGF-induced endothelial cell proliferation and migration. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001, 282, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfried, T.N.; Mukherjee, P. Ganglioside GM3 Is Antiangiogenic in Malignant Brain Cancer. J. Oncol. 2010, 2010, 961243. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, K.; Chava, A.K.; Mandal, C.; Dey, S.N.; Kniep, B.; Chandra, S.; Mandal, C. O-acetylation of GD3 prevents its apoptotic effect and promotes survival of lymphoblasts in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. J. Cell. Biochem. 2008, 105, 724–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, T.W.; Kim, S.J.; Choi, H.J.; Kim, K.J.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, H.J.; Ko, J.H.; Lee, Y.C.; Suzuki, A.; et al. Ganglioside GM3 inhibits VEGF/VEGFR-2-mediated angiogenesis: direct interaction of GM3 with VEGFR-2. Glycobiology 2009, 19, 229–239. [Google Scholar]

- Abate, L.E.; Mukherjee, P.; Seyfried, T.N. Gene-linked shift in ganglioside distribution influences growth and vascularity in a mouse astrocytoma. J. Neurochem. 2006, 98, 1973–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Sison, K.; Li, C.; Tian, R.; Wnuk, M.; Sung, H.K.; Jeansson, M.; Zhang, C.; Tucholska, M.; Jones, N.; et al. Soluble FLT1 binds lipid microdomains in podocytes to control cell morphology and glomerular barrier function. Cell 2012, 151, 384–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, R.; Jin, J.; Taylor, L.; Larsen, B.; Quaggin, S.E.; Pawson, T. Rapid and sensitive MRM-based mass spectrometry approach for systematically exploring ganglioside-protein interactions. Proteomics 2013, 13, 1334–1338. [Google Scholar]

- Tagami, S.; Inokuchi, J.; Kabayama, K.; Yoshimura, H.; Kitamura, F.; Uemura, S.; Ogawa, C.; Ishii, A.; Saito, M.; Ohtsuka, Y.; et al. Ganglioside GM3 participates in the pathological conditions of insulin resistance. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 3085–3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekimoto, J.; Kabayama, K.; Gohara, K.; Inokuchi, J. Dissociation of the insulin receptor from caveolae during TNFα-induced insulin resistance and its recovery by D-PDMP. FEBS Lett. 2012, 586, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabayama, K.; Sato, T.; Kitamura, F.; Uemura, S.; Kang, B.W.; Igarashi, Y.; Inokuchi, J. TNFalpha-induced insulin resistance in adipocytes as a membrane microdomain disorder: Involvement of ganglioside GM3. Glycobiology 2005, 15, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita, T.; Hashiramoto, A.; Haluzik, M.; Mizukami, H.; Beck, S.; Norton, A.; Kono, M.; Tsuji, S.; Daniotti, J.L.; Werth, N.; et al. Enhanced insulin sensitivity in mice lacking ganglioside GM3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003, 100, 3445–3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshizumi, S.; Suzuki, S.; Hirai, M.; Hinokio, Y.; Yamada, T.; Yamada, T.; Tsunoda, U.; Aburatani, H.; Yamaguchi, K.; Miyagi, T.; Oka, Y. Increased hepatic expression of ganglioside-specific sialidase, NEU3, Improves insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance in mice. Metabolism 2007, 56, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabayama, K.; Sato, T.; Saito, K.; Loberto, N.; Prinetti, A.; Sonnino, S.; Kinjo, M.; Igarashi, Y.; Inokuchi, J. Dissociation of the insulin receptor and caveolin-1 complex by ganglioside GM3 in the state of insulin resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007, 104, 13678–13683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, A.; Hata, K.; Suzuki, S.; Sawada, M.; Wada, T.; Yamaguchi, K.; Obinata, M.; Tateno, H.; Suzuki, H.; Miyagi, T. Overexpression of plasma membrane-associated sialidase attenuates insulin signaling in transgenic mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 27896–27902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rillahan, C.D.; Paulson, J.C. Glycan microarrays for decoding the glycome. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2011, 80, 797–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, M.R.; Whitman, C.M.; Kohler, J.J. Metabolically incorporated photocrosslinking sialic acid covalently captures a ganglioside-protein complex. Mol. Biosyst. 2010, 6, 1796–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Julien, S.; Bobowski, M.; Steenackers, A.; Le Bourhis, X.; Delannoy, P. How Do Gangliosides Regulate RTKs Signaling? Cells 2013, 2, 751-767. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells2040751

Julien S, Bobowski M, Steenackers A, Le Bourhis X, Delannoy P. How Do Gangliosides Regulate RTKs Signaling? Cells. 2013; 2(4):751-767. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells2040751

Chicago/Turabian StyleJulien, Sylvain, Marie Bobowski, Agata Steenackers, Xuefen Le Bourhis, and Philippe Delannoy. 2013. "How Do Gangliosides Regulate RTKs Signaling?" Cells 2, no. 4: 751-767. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells2040751