Genetic Dissection of Disease Resistance to the Blue Mold Pathogen, Peronospora tabacina, in Tobacco

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

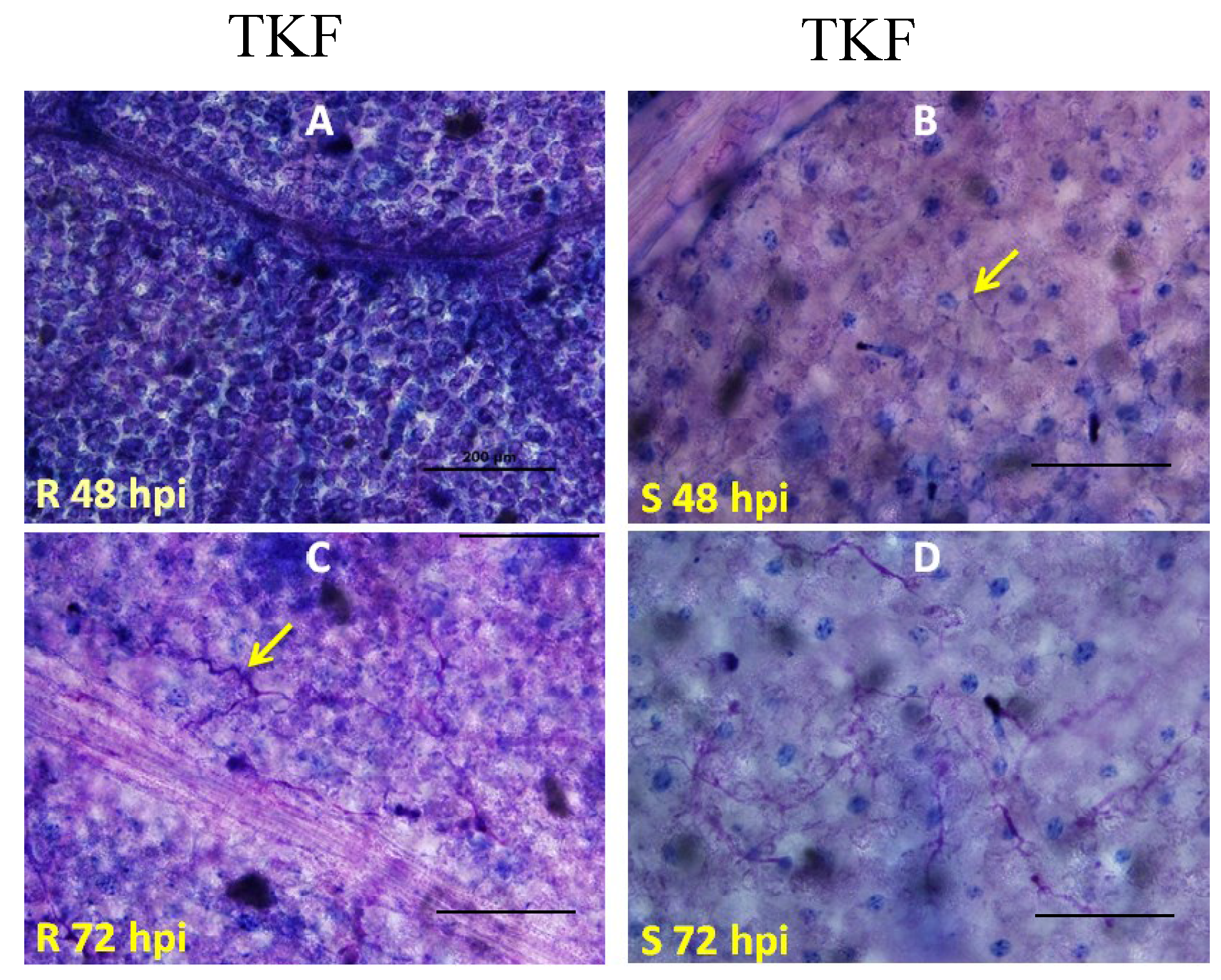

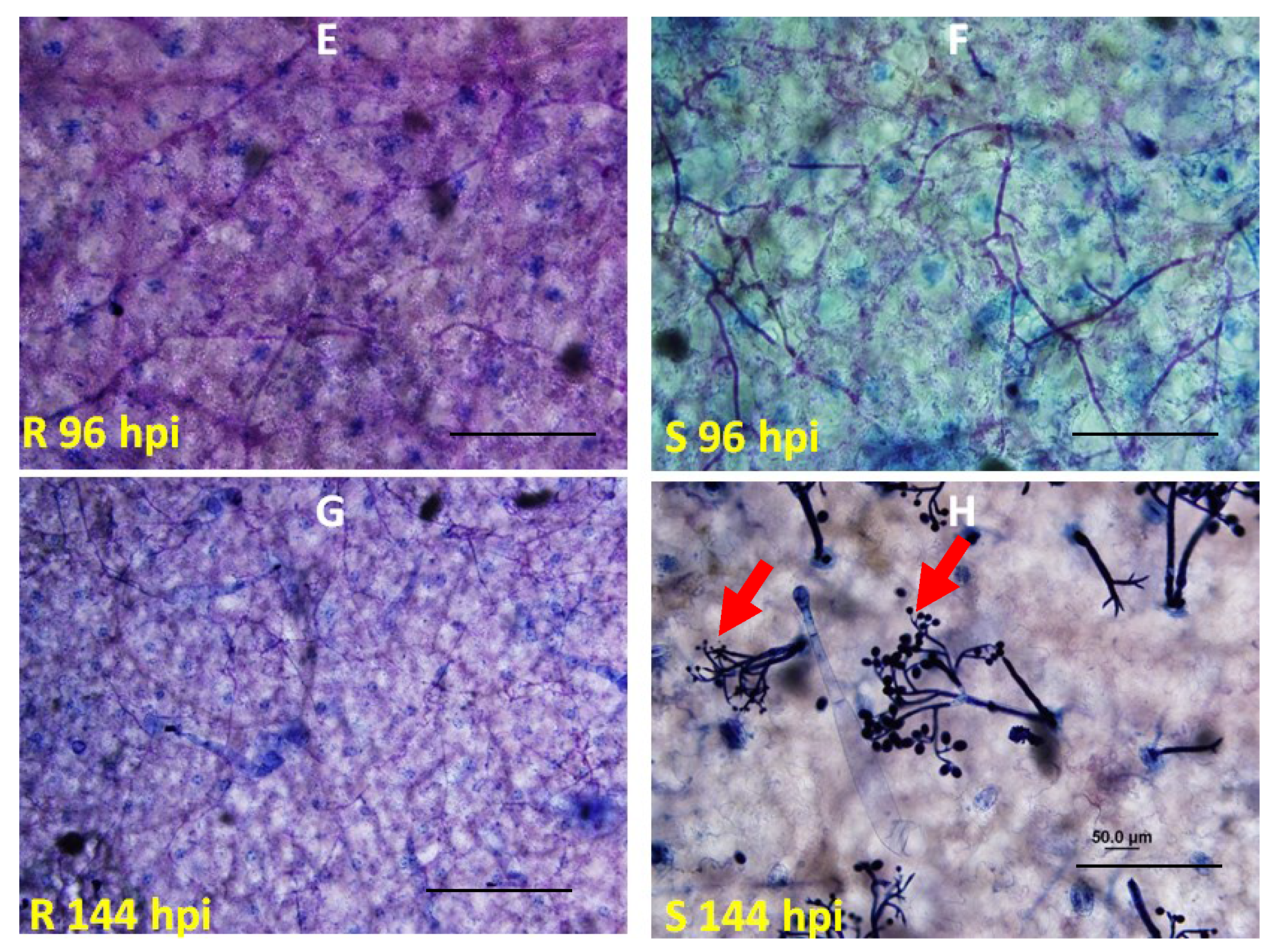

2.1. Disease Reaction Assay and Segregation Analysis

2.2. Genetic Mapping of RBM1

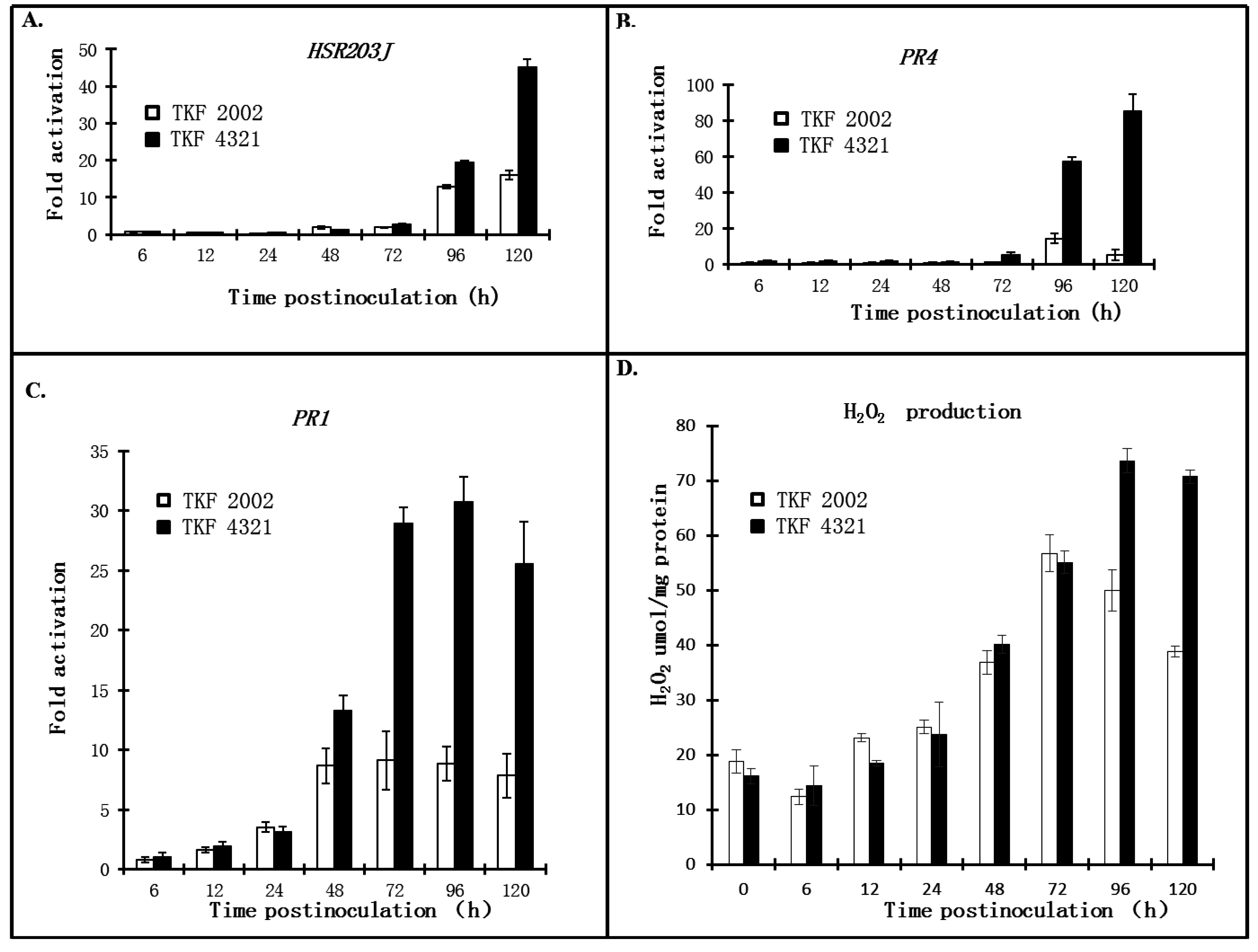

2.3. Quantitative Analysis of Defense Responses to Blue Mold Infection

3. Discussion

4. Experimental Section

4.1. The Mapping Population

4.2. P. tabacina Culture and Inoculation

4.3. Microscopic Analysis of Inoculated Leaves

4.4. Quantification of Endogenous Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in Tobacco Leaves

4.5. Real-Time PCR

4.6. Genetic Mapping and Marker Design

| Marker Name | Marker Type | Left Primer | Right Primer |

|---|---|---|---|

| PT53422 | SSR | CGCACATACGTACTGAGCATT | GGCTCGAACCCGTAACCTAT |

| PT61472 | SSR | TCCAATACCTTTAATGCATCTCC | GCATGACATGTTGAAGTGGG |

| PT61512Y | SSR | ATCGGACCCAAAGTTTAAGAAACAA | AGGCAAGGATAGGGATAGGAATAGC |

| PT51405 | SSR | AAGTTGGTTATAATCTCGATGCC | AATTCATCTCCAACGCAACTG |

| PT52753 | SSR | TTGGGCCTAGTTTCTACGGA | CAATGCTAACCTGTCACTACCA |

| PT60799 | SSR | GCCGCAGTACTAAAGCTCAGA | TGCACAATCTTCAGGTCAGC |

| PT54257 | SSR | GCAGCACCCAAGTTGCTTA | CCGTCTATTAGCATCAAGGCA |

| SCAR1 | SCAR | CTGAGTTTGGCCGAATAGCAT | CAAACGTCCTAAATGGGGTATAA |

| SCAR2 | SCAR | GTCTACGGCAAGGGGAGATATTA | GTCTACGGCAGCAATCAACATG |

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Files

Supplementary File 1Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sierro, N.; Battey, J.N.; Ouadi, S.; Bakaher, N.; Bovet, L.; Willig, A.; Goepfert, S.; Peitsch, M.C.; Ivanov, N.V. The tobacco genome sequence and its comparison with those of tomato and potato. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Du, Y.; Chen, S.; Tang, H. Dynamic metabonomic responses of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) plants to salt stress. J. Proteome Res. 2011, 10, 1904–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caplan, J.L.; Mamillapalli, P.; Burch-Smith, T.M.; Czymmek, K.; Dinesh-Kumar, S.P. Chloroplastic protein NRIP1 mediates innate immune receptor recognition of a viral effector. Cell 2008, 132, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitham, S.; Dinesh-Kumar, S.P.; Choi, D.; Hehl, R.; Corr, C.; Baker, B. The product of the tobacco mosaic virus resistance gene N: Similarity to toll and the interleukin-1 receptor. Cell 1994, 78, 1101–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heist, E.P.; Nesmith, W.C.; Schardl, C.L. Interactions of Peronospora tabacina with Roots of Nicotiana spp. in Gnotobiotic Associations. Phytopathology 2002, 92, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiltz, P. Downy mildew of tobacco. In The Downy Mildews; Spencer, D.M., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1981; pp. 577–599. [Google Scholar]

- Rufty, R.C. Genetics of host resistance to tobacco blue mold. In Blue Mold of Tobacco; McKean, W.E., Ed.; American Phytopathological Society: St. Paul, MN, USA, 1989; pp. 141–164. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, E.E. The transfer of blue mold resistance from Nicotiana debneyi. Part III. Development of a blue mold resistant cigar wrapper variety. Tob. Sci. 1967, 11, 107–110. [Google Scholar]

- Milla, S.R.; Levin, J.S.; Lewis, R.S.; Rufty, R.C. RAPD and SCAR markers linked to an introgressed gene conditioning resistance to Peronospora tabacina D.B. Adam. in tobacco. Crop Sci. 2005, 45, 2346–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wark, D.C. Nicotiana species as sources of resistance to blue mold (Peronospora tabacina Adam) for cultivated tobacco. In Proceedings of the 3rd World Tobacco Science Congress, Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia, 18–26 February 1963; Tobacco Research Board: Harare, Zimbabwe, 1963; pp. 252–259. [Google Scholar]

- Wark, D.C. Development of flue-cured tobacco cultivars resistant to a common strain of blue mold. Tob. Sci. 1970, 147–150. [Google Scholar]

- Rufty, R.C.; Main, C.E. Components of partial resistance to blue mold in six tobacco genotypes under controlled environmental conditions. Phytopathology 1989, 79, 606–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuttke, H.H. Blue mould resistance in tobacco. Aust. Tob. Grow. Bull 1972, 20, 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Julio, E.; Verrier, J.L.; Dorlhac de Borne, F. Development of SCAR markers linked to three disease resistances based on AFLP within Nicotiana tabacum L. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2006, 112, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bindler, G.; Plieske, J.; Bakaher, N.; Gunduz, I.; Ivanov, N.; van der Hoeven, R.; Ganal, M.; Donini, P. A high density genetic map of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) obtained from large scale microsatellite marker development. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2011, 123, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontier, D.; Gan, S.; Amasino, R.M.; Roby, D.; Lam, E. Markers for hypersensitive response and senescence show distinct patterns of expression. Plant Mol. Biol. 1999, 39, 1243–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tudzynski, P.; Heller, J.; Siegmund, U. Reactive oxygen species generation in fungal development and pathogenesis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2012, 15, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond-Kosack, K.E.; Tang, S.; Harrison, K.; Jones, J.D. The tomato Cf-9 disease resistance gene functions in tobacco and potato to confer responsiveness to the fungal avirulence gene product avr 9. Plant Cell 1998, 10, 1251–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, T.H.; Dahlbeck, D.; Clark, E.T.; Gajiwala, P.; Pasion, R.; Whalen, M.C.; Stall, R.E.; Staskawicz, B.J. Expression of the Bs2 pepper gene confers resistance to bacterial spot disease in tomato. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 14153–14158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thilmony, R.L.; Chen, Z.; Bressan, R.A.; Martin, G.B. Expression of the tomato Pto gene in tobacco enhances resistance to Pseudomonas syringae pv tabaci expressing avrPto. Plant Cell 1995, 7, 1529–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitham, S.; McCormick, S.; Baker, B. The N gene of tobacco confers resistance to tobacco mosaic virus in transgenic tomato. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 8776–8781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baudouni, E.; Charpenteau, M.; Roby, D.; Marco, Y.; Ranjeva, R.; Ranty, B. Functional expression of a tobacco gene related to the serine hydrolase family—Esterase activity towards short-chain dinitrophenyl acylesters. Eur. J. Biochem. 1997, 248, 700–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontier, D.; Tronchet, M.; Rogowsky, P.; Lam, E.; Roby, D. Activation of hsr203, a plant gene expressed during incompatible plant-pathogen interactions, is correlated with programmed cell death. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 1998, 11, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontier, D.; Balague, C.; Bezombes-Marion, I.; Tronchet, M.; Deslandes, L. Identification of a novel pathogen-responsive element in the promoter of the tobacco gene HSR203J, a molecular marker of the hypersensitive response. Plant J. 2001, 26, 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, Y.; Uehara, Y.; Berberich, T.; Ito, A.; Saitoh, H.; Miyazaki, A.; Terauchi, R.; Kusano, T. A subset of hypersensitive response marker genes, including HSR203J, is the downstream target of a spermine signal transduction pathway in tobacco. Plant J. 2004, 40, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Biezen, E.A.; Jones, J.D. Plant disease-resistance proteins and the gene-for-gene concept. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1998, 23, 454–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, J.M.; Woffenden, B.J. Plant disease resistance genes: Recent insights and potential applications. Trends Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Loon, L.C.; van Kammen, A. Polyacrylamide disc electrophoresis of the soluble leaf proteins from Nicotiana tabacum var. “Samsun” and “Samsun NN”. II. Changes in protein constitution after infection with tobacco mosaic virus. Virology 1970, 40, 190–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomma, B.P.; Eggermont, K.; Penninckx, I.A.; Mauch-Mani, B.; Vogelsang, R.; Cammue, B.P.; Broekaert, W.F. Separate jasmonate-dependent and salicylate-dependent defense-response pathways in Arabidopsis are essential for resistance to distinct microbial pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 15107–15111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, D.; Goodman, R.M.; Gut-Rella, M.; Glascock, C.; Weymann, K.; Friedrich, L.; Maddox, D.; Ahl-Goy, P.; Luntz, T.; Ward, E.; et al. Increased tolerance to two oomycete pathogens in transgenic tobacco expressing pathogenesis-related protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 7327–7331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lusso, M.; Kuc, J. The effect of sense and antisense expression of the PR-N gene for β-1,3-glucanase on disease resistance of tobacco to fungi and viruses. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 1996, 49, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Willits, M.G.; Glazebrook, J. Arabidopsis thaliana EDS4 contributes to salicylic acid (SA)-dependent expression of defense responses: Evidence for inhibition of jasmonic acidsignaling by SA. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2000, 13, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koornneef, A.; Leon-Reyes, A.; Ritsema, T.; Verhage, A.; Den Otter, F.C.; van Loon, L.C.; Pieterse, C.M. Kinetics of salicylate-mediated suppression of jasmonate signaling reveal a role for redox modulation. Plant Physiol. 2008, 147, 1358–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spoel, S.H.; Koornneef, A.; Claessens, S.M.C.; Korzelius, J.P.; van Pelt, J.A.; Dong, X.; Pieterse, C.M. NPR1 modulates cross-talk between salicylate- and jasmonate-dependent defense pathways through a novel function in the cytosol. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 760–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mur, L.A.; Kenton, P.; Atzorn, R.; Miersch, O.; Wasternack, C. The outcomes of concentration-specific interactions between salicylate and jasmonate signaling include synergy, antagonism, and oxidative stress leading to cell death. Plant Physiol. 2006, 140, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Gao, M.; Zaitlin, D. Molecular linkage mapping and marker-trait associations with NlRPT, a downy mildew resistance gene in Nicotiana langsdorffii. Front. Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Zaitlin, D. Genetic resistance to Peronospora tabacina in Nicotiana langsdorffii, a South American wild tobacco. Phytopathology 2008, 98, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heist, E.P.; Zaitlin, D.; Funnell, D.L.; Nesmith, W.C.; Schardl, C.L. Necrotic lesion resistance induced by Peronospora tabacina on Leaves of Nicotiana obtusifolia. Phytopathology 2004, 94, 1178–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reuveni, M.; Nesmith, W.C.; Siegel, M.R. Symptom development and disease severity in Nicotiana tabacum and N. repanda caused by Peronospora tabacina. Plant Dis. 1986, 70, 727–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh, R.C.; Deverall, B.J.; McLeod, S. Comparison of histological and physiological responses to Phakopsora pachyrhizi in resistant and susceptible soybean. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1980, 74, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, B.; Venugopal, S.C.; Kulshrestha, S.; Navarre, D.A.; Downie, B.; Vaillancourt, L.; Kachroo, A.; Kachroo, P. Glycerol-3-phosphate levels are associated with basal resistance to the hemibiotrophic fungus Colletotrichum higginsianum in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2008, 147, 2017–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lander, E.S.; Green, P.; Abrahamson, J.; Barlow, A.; Daly, M.J.; Lincoln, S.E.; Newburg, L. MAPMAKER: An interactive computer package for constructing primary genetic maps of experimental and natural populations. Genomics 1987, 1, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, X.; Li, D.; Bao, Y.; Zaitlin, D.; Miller, R.; Yang, S. Genetic Dissection of Disease Resistance to the Blue Mold Pathogen, Peronospora tabacina, in Tobacco. Agronomy 2015, 5, 555-568. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy5040555

Wu X, Li D, Bao Y, Zaitlin D, Miller R, Yang S. Genetic Dissection of Disease Resistance to the Blue Mold Pathogen, Peronospora tabacina, in Tobacco. Agronomy. 2015; 5(4):555-568. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy5040555

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Xia, Dandan Li, Yinguang Bao, David Zaitlin, Robert Miller, and Shengming Yang. 2015. "Genetic Dissection of Disease Resistance to the Blue Mold Pathogen, Peronospora tabacina, in Tobacco" Agronomy 5, no. 4: 555-568. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy5040555