Immobilization Effects on the Catalytic Properties of Two Fusarium Verticillioides Lipases: Stability, Hydrolysis, Transesterification and Enantioselectivity Improvement

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

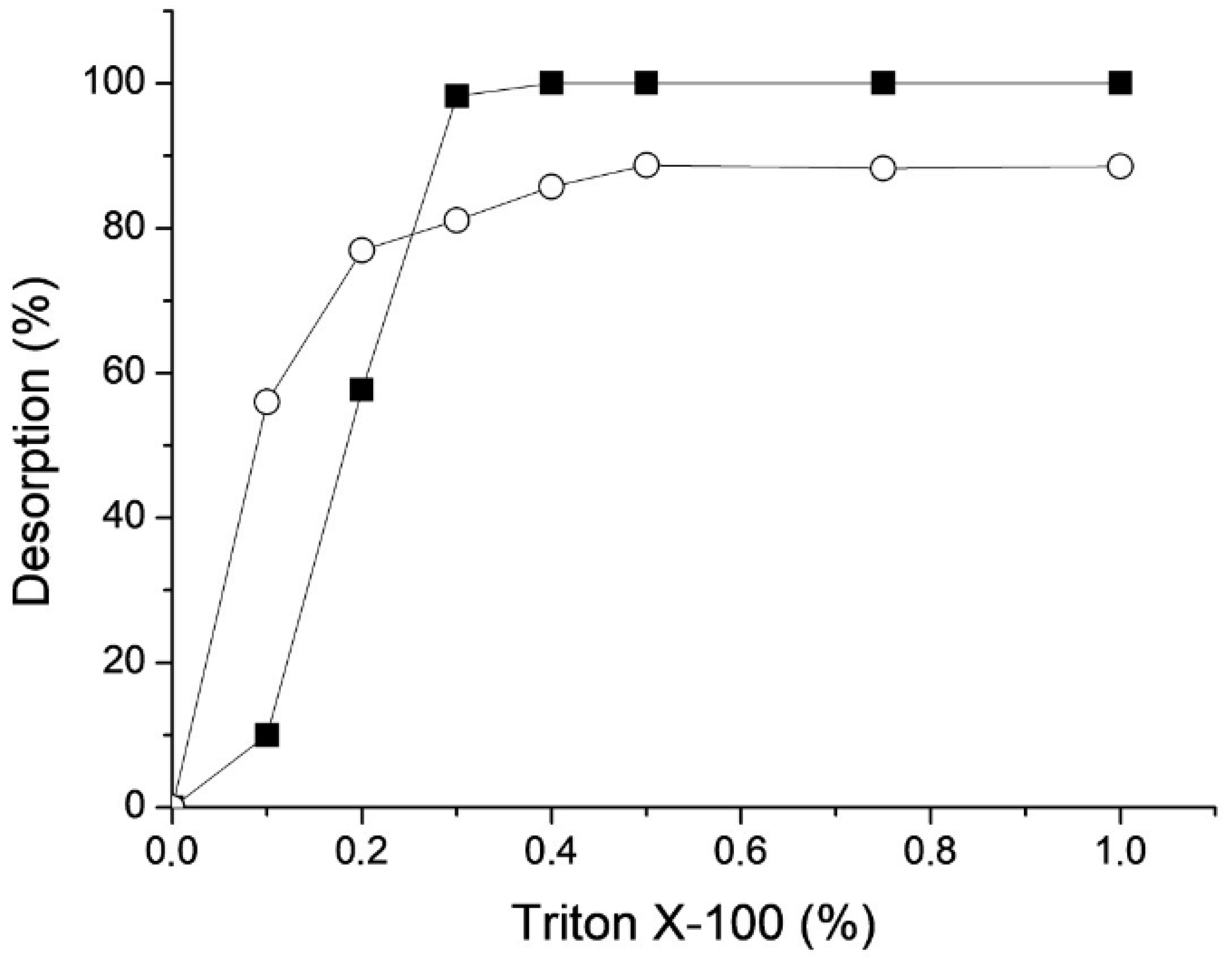

2.1. Hydrophobic Immobilization

2.2. Cascade Purification of Two Lipases

2.3. Thermal Stability of Derivatives

2.4. Biochemical Characterization of Purified and Free Lipases

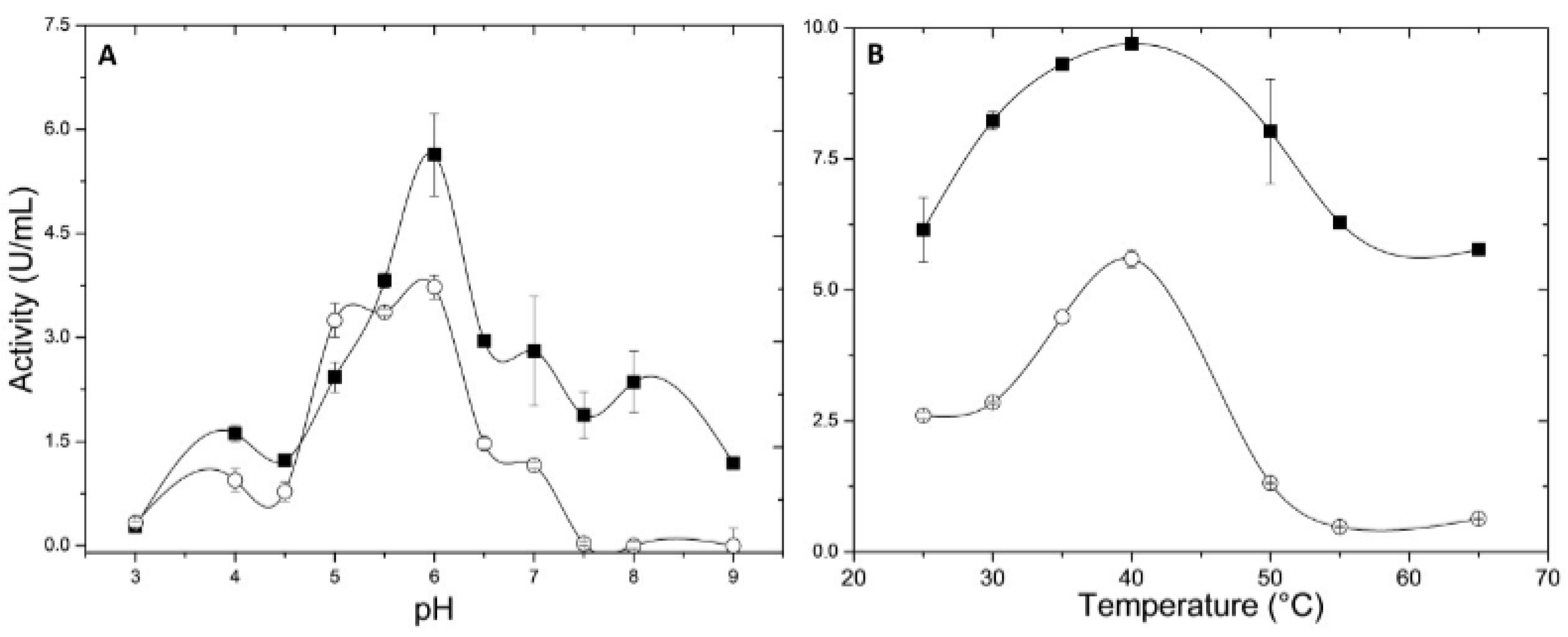

2.4.1. pH and Temperature Effects

2.4.2. Effect of Metallic Ions

2.4.3. Isoelectric Point and Kinetic Parameters

2.5. Lip1 and Lip 2 Biotechnological Applications

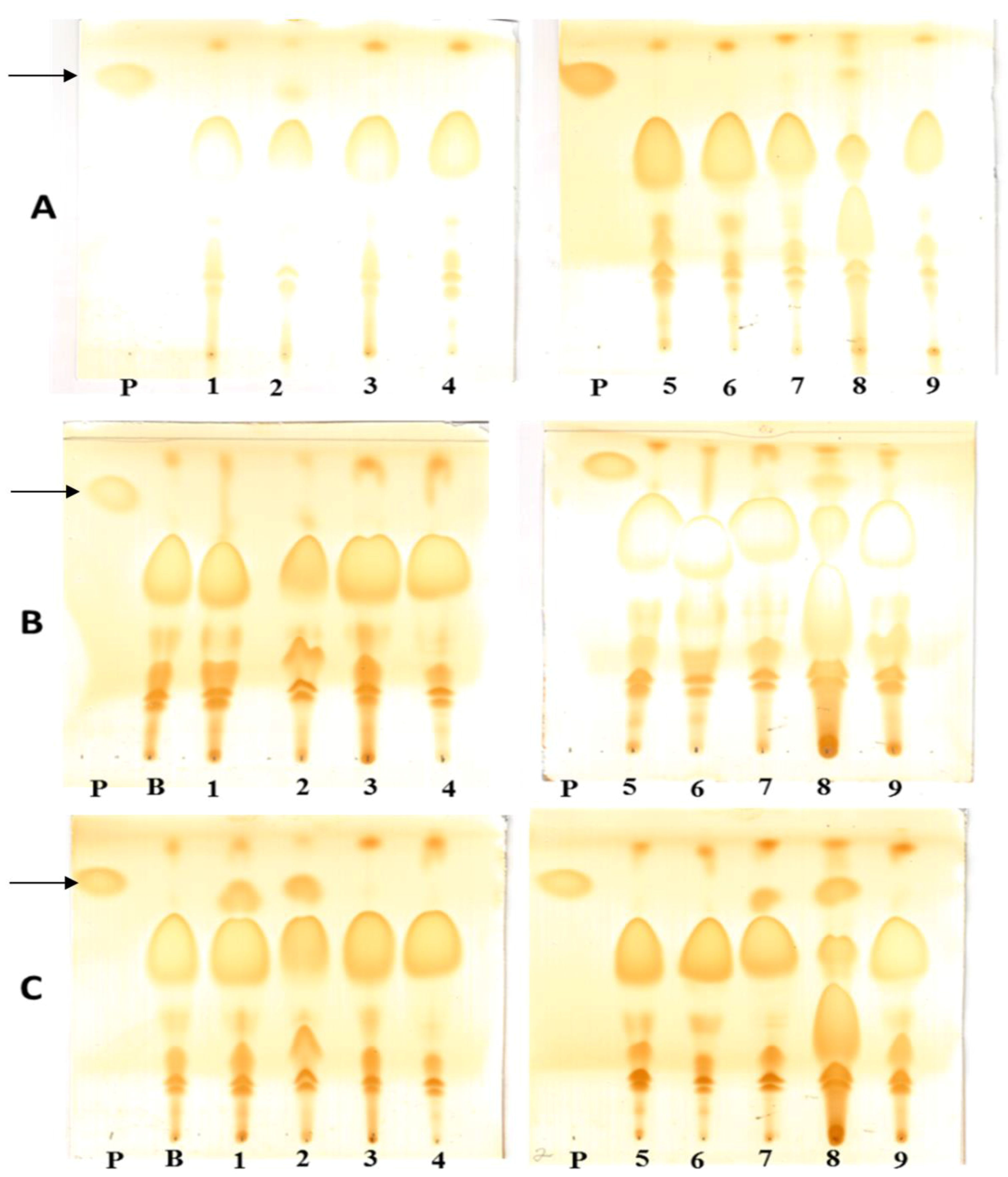

2.5.1. Transesterification Reaction Applications

2.5.2. Ethanolysis of Sardine Oil

2.5.3. Sardine Oil Hydrolysis

2.5.4. Hydrolysis of Racemic Mixtures

2-O-butyryl-2-phenylacetic

HPBE Hydrolysis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Microorganism and Culture Maintenance

3.2. Lipase Production

3.3. Measurement of Lipase Activity

3.3.1. p-Nitrophenyl Butyrate (pNPB)

3.3.2. p-Nitrophenyl Palmitate (pNPP)

3.4. Lipase Hydrophobic Immobilization

3.5. Hydrophobic Derivatives Thermal Stability

3.6. Cascade Purification

3.7. Enzyme Desorption

3.8. Immobilization of the Lipase on CNBr-Activated Support

3.9. Biochemical Characterization of Lipases

3.9.1. Temperature and pH Influence

3.9.2. Effect of Metallic Ions

3.9.3. Isoelectric Point and Kinetic Parameters

3.10. Hydrolysis of Sardine Oil

3.11. Ethanolysis of Sardine Oil

3.12. Hydrolysis of Racemic Mixtures

3.13. Transesterification Reaction

3.14. Thin Layer Chromatography Analysis (TLC)

3.15. Transesterification Assay by Gas Chromatography (CG-MS)

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cunha, A.G.; Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Gutarra, M.L.E.; Bevilaqua, J.V.; Almeida, R.V.; Paiva, L.M.C.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Guisan, J.M.; Freire, D.M.G. Separation and immobilization of lipase from Penicillium simplicissimum by selective adsorption on hydrophobic supports. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2009, 156, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Pizarro, C.; Lopez-Vela, D.; Betancor, L.; Carrascosa, A.V.; Pessela, B.; Guisan, J.M. Hydrolysis of fish oil by lipases immobilized inside porous supports. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2011, 88, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Betancor, L.; Carrascosa, A.V.; Palomo, J.M.; Guisan, J.M. Modulation of the selectivity of immobilized lipases by chemical and physical modifications: Release of Omega-3 fatty acids from fish oil. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2012, 89, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, Z.; Palomo, J.M. Enantioselective desymmetrization of prochiral diesters catalyzed by immobilized Rhizopus oryzae lipase. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2011, 22, 2080–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, A.; Filice, M.; Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Palomo, J.M.; Guisan, J.M. Kinetically controlled synthesis of monoglyceryl esters from chiral and prochiral acids methyl esters catalyzed by immobilized Rhizomucor miehei lipase. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Filice, M.; Lopez-Vela, D.; Pizarro, C.; Wilson, L.; Betancor, L.; Avila, Y.; Guisan, J.M. Cross-Linking of lipases adsorbed on hydrophobic supports: Highly selective hydrolysis of fish oil catalyzed by RML. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2011, 88, 801–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filice, M.; Marciello, M.; Betancor, L.; Carrascosa, A.V.; Guisan, J.M.; Fernandez-Lorente, G. Hydrolysis of fish oil by hyperactivated Rhizomucor miehei lipase immobilized by multipoint anion exchange. Biotechnol. Prog. 2011, 27, 961–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizarro, C.; Branes, M.C.; Markovits, A.; Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Guisan, J.M.; Chamy, R.; Wilson, L. Influence of different immobilization techniques for Candida cylindracea lipase on its stability and fish oil hydrolysis. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2012, 78, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.C.; Bolivar, J.M.; Palau-Ors, A.; Volpato, G.; Ayub, M.A.Z.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Guisan, J.M. Positive effects of the multipoint covalent immobilization in the reactivation of partially inactivated derivatives of lipase from Thermomyces lanuginosus. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2009, 44, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brabcova, J.; Demianova, Z.; Vondrasek, J.; Jagr, M.; Zarevucka, M.; Palomo, J.M. Highly selective purification of three lipases from Geotrichum candidum 4013 and their characterization and biotechnological applications. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2013, 98, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomo, J.M.; Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Mateo, C.; Ortiz, C.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Guisan, J.M. Modulation of the enantioselectivity of lipases via controlled immobilization and medium engineering: Hydrolytic resolution of mandelic acid esters. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2002, 31, 775–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomo, J.M.; Munoz, G.; Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Mateo, C.; Fuentes, M.; Guisan, J.M.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Modulation of Mucor miehei lipase properties via directed immobilization on different hetero-functional epoxy resins—Hydrolytic resolution of (R,S)-2-butyroyl-2-phenylacetic acid. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2003, 21, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Lozano, S.; Rodriguez-Gonzalez, J.A.; Mateos-Diaz, J.C.; Reyes-Duarte, D.; Favela-Torres, E. Catalytic profiles of lipolytic biocatalysts produced by filamentous fungi. Biocatal. Biotransform. 2012, 30, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Betancor, L.; Carrascosa, A.V.; Guisan, J.M. Release of Omega-3 fatty acids by the hydrolysis of fish oil catalyzed by lipases immobilized on hydrophobic supports. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2011, 88, 1173–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jallouli, R.; Khrouf, F.; Fendri, A.; Mechichi, T.; Gargouri, Y.; Bezzine, S. Purification and biochemical characterization of a novel alkaline (phospho)lipase from a newly isolated Fusarium solani strain. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2012, 168, 2330–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jallouli, R.; Fendri, A.; Mechichi, T.; Gargouri, Y.T.; Bezzine, S. Kinetic properties of a novel Fusarium solani (phospho)lipase: A monolayer study. Chirality 2013, 25, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tehreema, L. Process optimization for extracellular lipase production from Fusarium oxysporum (mbl21) through solid state fermentation technique. Clin. Biochem. 2011, 44, S243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastida, A.; Sabuquillo, P.; Armisen, P.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Huguet, J.; Guisan, J.M. Single step purification, immobilization and hyperactivation of lipases via interfacial adsorption on strongly hydrophobic supports. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1998, 58, 486–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomo, J.M.; Munoz, G.; Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Mateo, C.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Guisan, J.M. Interfacial adsorption of lipases on very hydrophobic support (octadecyl-Sepabeads): Immobilization, hyperactivation and stabilization of the open form of lipases. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2002, 19, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.G.; Facchini, F.D.A.; Polizeli, A.M.; Vici, A.C.; Guisan, J.M.; Jorge, J.A.; Pessela, B.C.; Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Polizeli, M.L.T.M. Stabilization of the lipase of Hypocrea pseudokoningii by multipoint covalent immobilization after chemical modification and application of the biocatalyst in oil hydrolysis. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2015, 121, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Cabrera, Z.; Godoy, C.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Palomo, J.M.; Guisan, J.M. Interfacially activated lipases against hydrophobic supports: Effect of the support nature on the biocatalytic properties. Process Biochem. 2008, 43, 1061–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adan Gokbulut, A.; Arslanoglu, A. Purification and biochemical characterization of an extracellular lipase from psychrotolerant Pseudomonas fluorescens KE38. Turk. J. Biol. 2013, 37, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.G.; Vici, A.C.; Facchini, F.D.A.; Tristão, A.P.; Cursino-Santos, J.R.; Sanches, P.R.; Jorge, J.A.; Polizeli, M.L.T.M. Screening of filamentous fungi for lipase production: Hypocrea pseudokoningii a new producer with a high biotechnological potential. Biocatal. Biotransform. 2014, 32, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhetras, N.C.; Bastawde, K.B.; Gokhale, D.V. Purification and characterization of acidic lipase from Aspergillus niger NCIM 1207. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 1486–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polizelli, P.P.; Antonio Facchini, F.D.; Cabral, H.; Bonilla-Rodriguez, G.O. A new lipase isolated from oleaginous seeds from Pachira aquatica (Bombacaceae). Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2008, 150, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jermsuntiea, W.; Aki, T.; Toyoura, R.; Iwashita, K.; Kawamoto, S.; Ono, K. Purification and characterization of intracellular lipase from the polyunsaturated fatty acid-producing fungus Mortierella alliacea. New Biotechnol. 2011, 28, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shangguan, J.J.; Liu, Y.Q.; Wang, F.J.; Zhao, J.; Fan, L.Q.; Li, S.X.; Xu, J.H. Expression and Characterization of a novel lipase from Aspergillus fumigatus with high specific activity. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2011, 165, 949–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharti, M.K.; Khokhar, D.; Pandey, A.K.; Gaur, A.K. Purification and characterization of lipase from Aspergillus japonicus: A potent enzyme for biodiesel production. Natl. Acad. Sci. Lett. 2013, 36, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vici, A.C.; Cruz, A.F.; Facchini, F.D.A.; Carvalho, C.C.; Pereira, M.G.; Fonseca-Maldonado, R.; Ward, R.J.; Pessela, B.C.; Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Torres, F.A.G.; et al. Beauveria bassiana Lipase A expressed in Komagataella (Pichia) pastoris with potential for biodiesel catalysis. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulla, R.; Ravindra, P. Immobilized Burkholderia cepacia lipase for biodiesel production from crude Jatropha curcas L. oil. Biomass Bioenergy 2013, 56, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salis, A.; Pinna, M.; Monduzzi, M.; Solinas, V. Biodiesel production from triolein and short chain alcohols through biocatalysis. J. Biotechnol. 2005, 119, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, P.; Meng, X.H.; He, J.Z.; Sun, P.L. Analysis of immobilized Candida rugosa lipase catalyzed preparation of biodiesel from rapeseed soapstock. Food Bioprod. Process. 2008, 86, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Perez, S.; Guisan, J.M.; Fernandez-Lorente, G. Selective ethanolysis of fish oil catalyzed by immobilized lipases. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2014, 91, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Ortiz, C.; Segura, R.L.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Guisan, J.M.; Palomo, J.M. Purification of different lipases from Aspergillus niger by using a highly selective adsorption on hydrophobic supports. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2005, 92, 773–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Palomo, J.M.; Cabrera, Z.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Guisan, J.M. Improved catalytic properties of immobilized lipases by the presence of very low concentrations of detergents in the reaction medium. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2007, 97, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Facchini, F.D.A.; Vici, A.C.; Pereira, M.G.; Jorge, J.A.; Polizeli, M.L.T.M. Enhanced lipase production of Fusarium verticillioides by using response surface methodology and wastewater pretreatment application. J. Biochem. Technol. 2015, 6, 996–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Pencreach, G.; Baratti, J.C. Hydrolysis of p-nitrophenyl palmitate in n-heptane by the Pseudomonas cepacia lipase: A simple test for the determination of lipase activity in organic media. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 1996, 18, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlvaine, T.C. A buffer solution for colorimetric comparison. J. Biolog. Chem. 1921, 49, 183–186. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M.M. Rapid and sensitive method for quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Farrel, P.Z.; Goodman, H.M.; O’Farrel, P.H. High resolution two dimensional electrophoresis of basic as acidic proteins. Cell 1977, 12, 1133–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, F.A.; Degreve, L.; Baranauskas, J.A. SIGRAF: A versatile computer program for fitting enzyme kinetics data. Biochemistry 1992, 20, 94–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, F.A.; Baranauskas, J.A.; Furriel, R.P.M.; Borin, I.A. SIGRAFW: An easy-to-use program for fitting enzyme kinetic data. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Educ. 2005, 33, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Terreni, M.; Mateo, C.; Bastida, A.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Dalmases, P.; Huguet, J.; Guisan, J.M. Modulation of lipase properties in macro-aqueous systems by controlled enzyme immobilization: Enantioselective hydrolysis of a chiral ester by immobilized Pseudomonas lipase. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2001, 28, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Sharma, S.; Gupta, M.N. Biodiesel preparation by lipase-catalyzed transesterification of Jatropha oil. Energy Fuels 2004, 18, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Derivatives | Immobilization (%) | Fold * |

|---|---|---|

| Butyl Sepharose | 28.2 ± 2.0 | 0.1 |

| Phenyl Toyopearl | 50.0 ± 2.0 | 3.7 |

| Hexyl Toyopearl | 59.6 ± 0.8 | 2.6 |

| Octyl Sepharose | 74.3 ± 1.0 | 2.4 |

| Octadecyl Sepabeads | 89.3 ± 0.5 | 2.6 |

| Enzyme | Volume (mL) | Mass (g) | Total Activity (U) | Immobilization (%) | SA * (U/mg) | Recuperation (%) | PF ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude extract | 10 | - | 21.8 | - | 90.8 | 100 | 1 |

| Octyl | - | 1.0 | 9.7 | 70 | 194.0 | 44.5 | 2.14 |

| Octadecyl | - | 1.0 | 5.6 | 100 a | 373.3 | 25.7 | 4.11 |

| Lipase | Time (min) | Immobilization (%) |

|---|---|---|

| FVL1 | 30 | 53.5 |

| FVL2 | 30 | 38.3 |

| Enzyme | KM (mM) | Vmax (U·mg·protein−1) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/KM (M−1·s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lip1 | 0.16 | 47.71 | 2.00 × 109 | 1.25 × 1013 |

| Lip2 | 0.26 | 37.4 | 3.53 × 109 | 1.35 × 1013 |

| Samples | Oils | Conversion (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Ethyl oleate 1% | 100 | |

| Controls | Soy oil | 0.0 |

| Macaúba pulp oil | 0.29 | |

| Macaúba almond oil | 0.13 | |

| Olive oil | 0.0 | |

| Octadecyl Sepabeads (Lip2) | Soy oil | 1.71 |

| Macaúba pulp oil | 3.62 | |

| Macaúba almond oil | 1.28 | |

| Olive oil | 1.18 |

| Derivative | Ester | Conversion (%) | Selectivity (EPA/DHA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | EPA | nd * | nd * |

| DHA | nd * | ||

| Lip1 | EPA | 2.1 | 1.25 |

| DHA | 1.7 | ||

| Lip2 | EPA | 5.5 | 1.15 |

| DHA | 4.8 |

| Enzyme | Derivative | Selectivity (EPA/DHA) | EPA (%) | DHA (%) | Total Conversion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lip1 | Octyl | 14.72 | 6.00 | 2.40 | 8.40 |

| CNBr-activated | 19.57 | 1.50 | 0.40 | 1.90 | |

| Lip2 | Octadecyl | 13.89 | 1.80 | 0.80 | 2.60 |

| CNBr-activated | 2.84 | 1.00 | 0.60 | 1.60 | |

| Control | - | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.07 |

| Lipase | Derivatives | Time (h) | Conversion (%) | SA * (U/mg) | Selectivity (E) | ee | Isomer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lip1 | CNBr-activated | 240 | 1.7 | 0.25 | 1.0 | 21.2 | S |

| Octyl | 144 | 4.8 | 1.15 | 3.4 | 54.5 | S | |

| Lip2 | CNBr-activated | 336 | 2.0 | 0.28 | 1.3 | 13.6 | S |

| Octadecyl | 144 | 10.3 | 4.51 | 2.6 | 44.3 | S |

| Lipase | Derivatives | Time (h) | Conversion (%) | SA * (U/mg) | Selectivity E | ee | Isomer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lip1 | CNBr-activated | 96 | 18 | 6.51 | 2.1 | 35.7 | S |

| Octyl | 1.5 | 6.9 | 159.7 | 3.7 | 57.6 | S | |

| Lip2 | CNBr-activated | 96 | 10.8 | 5.4 | 1.4 | 17.8 | R |

| Octadecyl | 96 | 10.8 | 7.13 | 3.6 | 56.2 | S |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Facchini, F.D.A.; Pereira, M.G.; Vici, A.C.; Filice, M.; Pessela, B.C.; Guisan, J.M.; Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Polizeli, M.D.L.T.d.M. Immobilization Effects on the Catalytic Properties of Two Fusarium Verticillioides Lipases: Stability, Hydrolysis, Transesterification and Enantioselectivity Improvement. Catalysts 2018, 8, 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal8020084

Facchini FDA, Pereira MG, Vici AC, Filice M, Pessela BC, Guisan JM, Fernandez-Lorente G, Polizeli MDLTdM. Immobilization Effects on the Catalytic Properties of Two Fusarium Verticillioides Lipases: Stability, Hydrolysis, Transesterification and Enantioselectivity Improvement. Catalysts. 2018; 8(2):84. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal8020084

Chicago/Turabian StyleFacchini, Fernanda Dell Antonio, Marita Gimenez Pereira, Ana Claudia Vici, Marco Filice, Benevides Costa Pessela, Jose Manuel Guisan, Glória Fernandez-Lorente, and Maria De Lourdes Teixeira de Moraes Polizeli. 2018. "Immobilization Effects on the Catalytic Properties of Two Fusarium Verticillioides Lipases: Stability, Hydrolysis, Transesterification and Enantioselectivity Improvement" Catalysts 8, no. 2: 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal8020084