Effect of Ce/Y Addition on Low-Temperature SCR Activity and SO2 and H2O Resistance of MnOx/ZrO2/MWCNTs Catalysts

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. SCR Performance

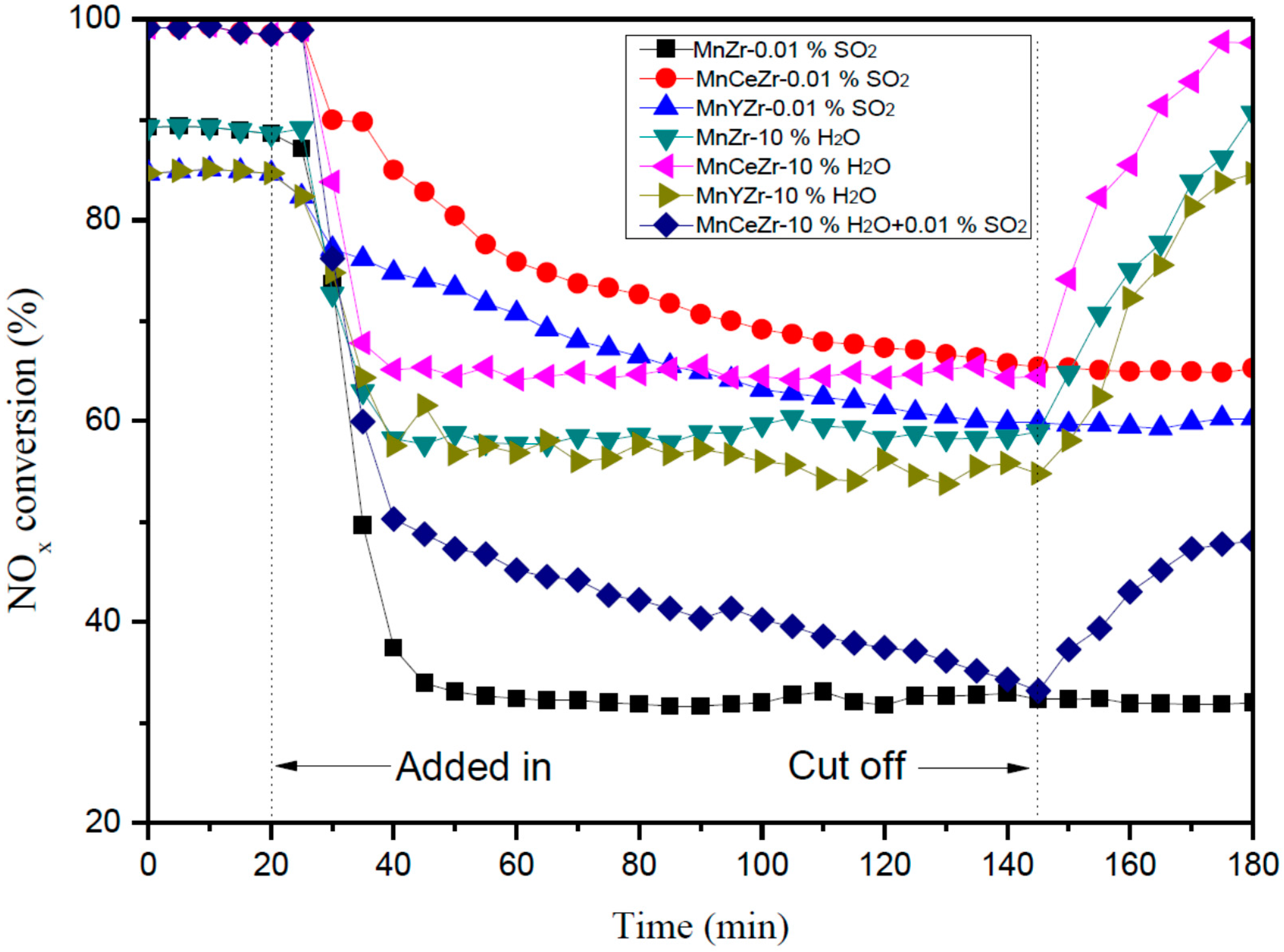

2.2. Effect of SO2 on SCR Catalytic Activity

2.3. Effect of H2O on SCR Catalytic Activity

2.4. Effect of H2O and SO2 on SCR Catalytic Activity

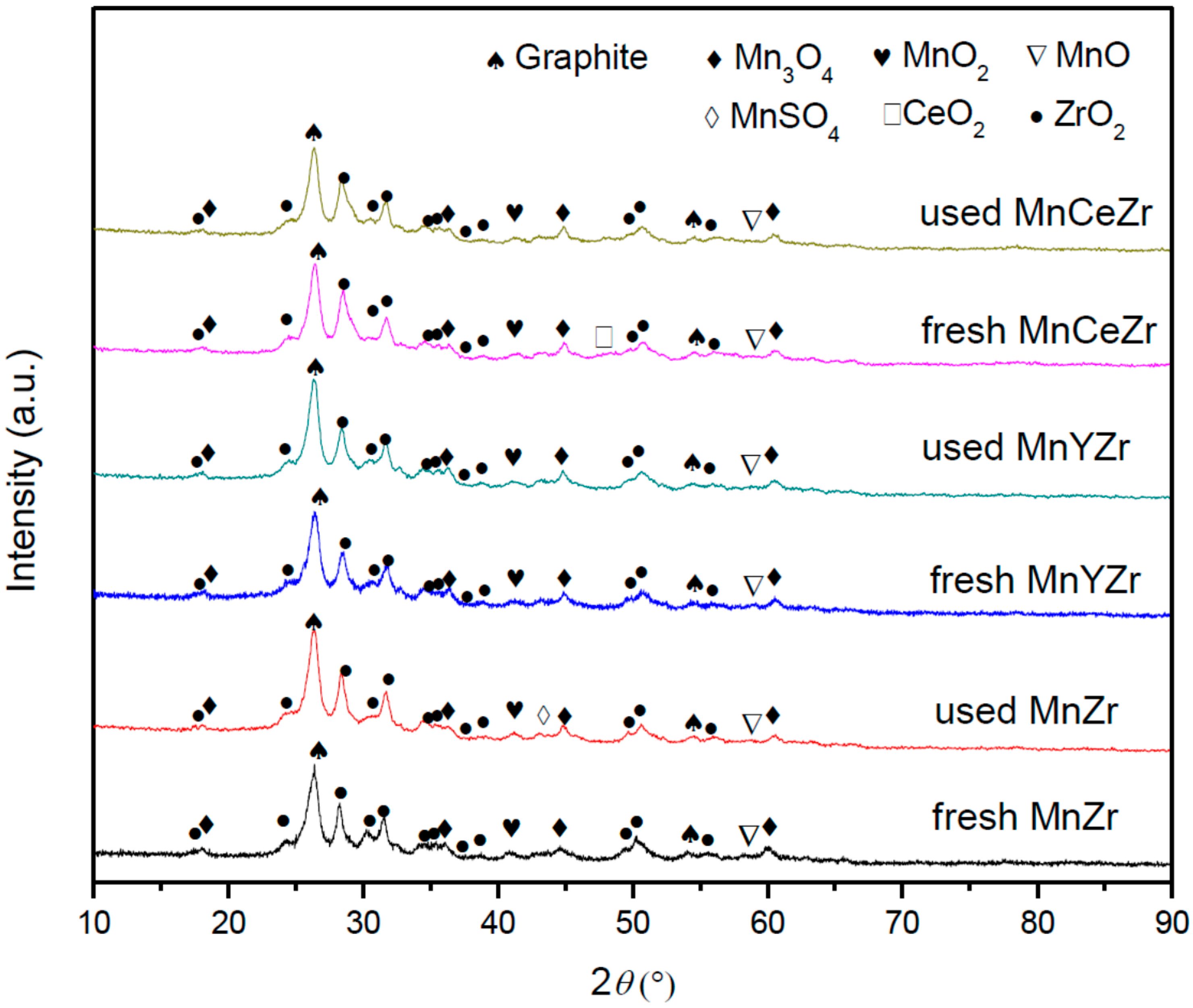

2.5. XRD Results

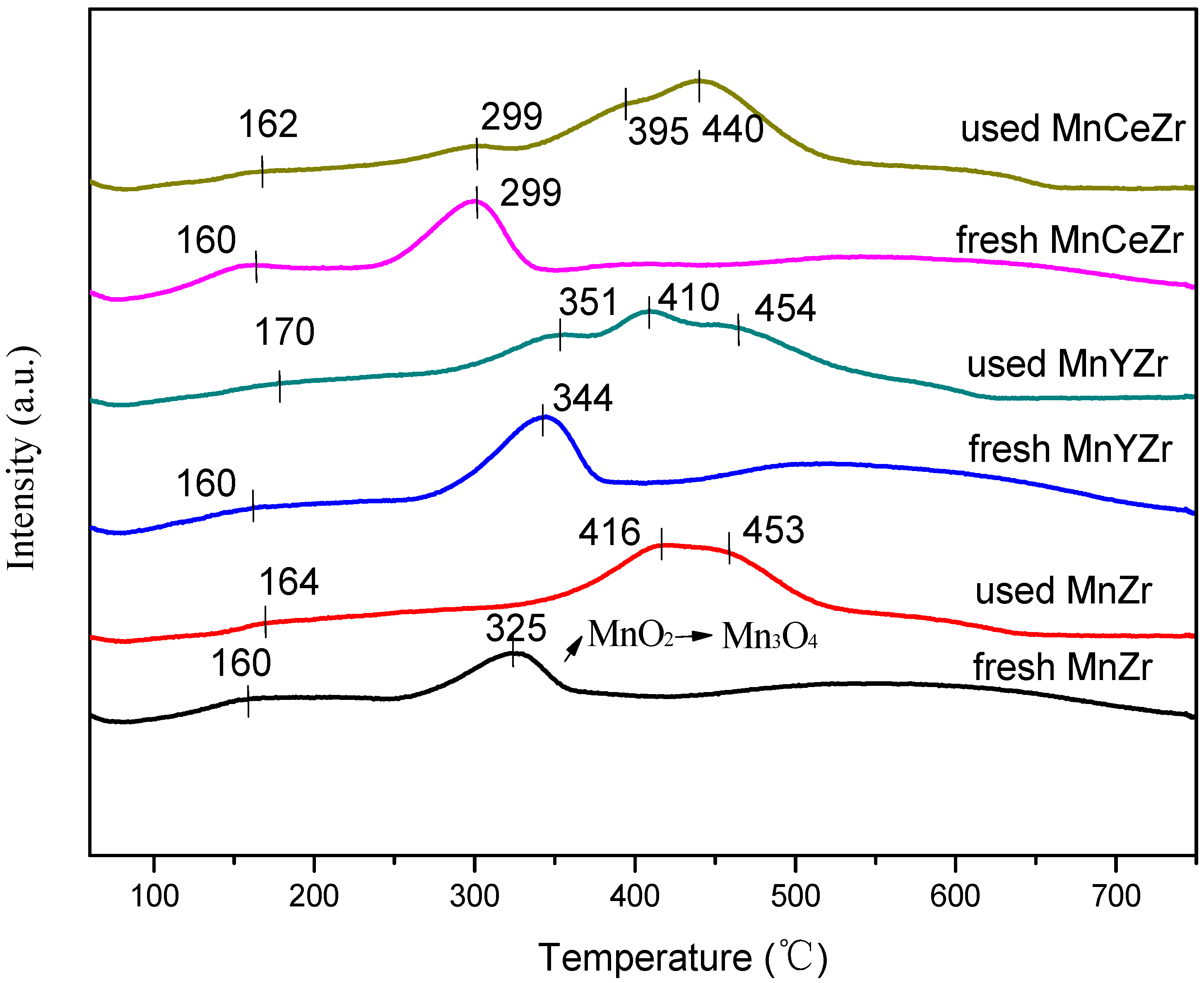

2.6. H2-TPR Results

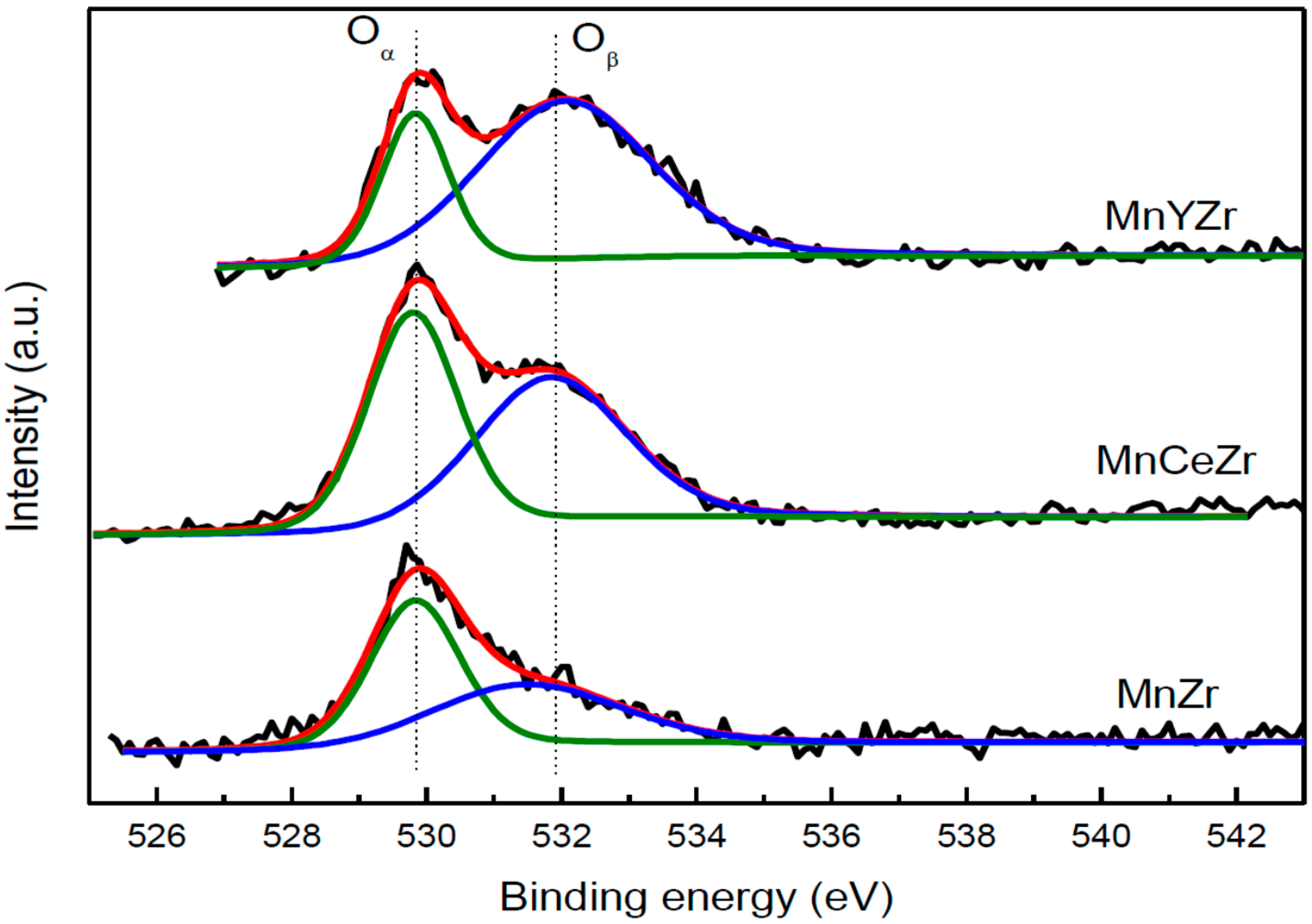

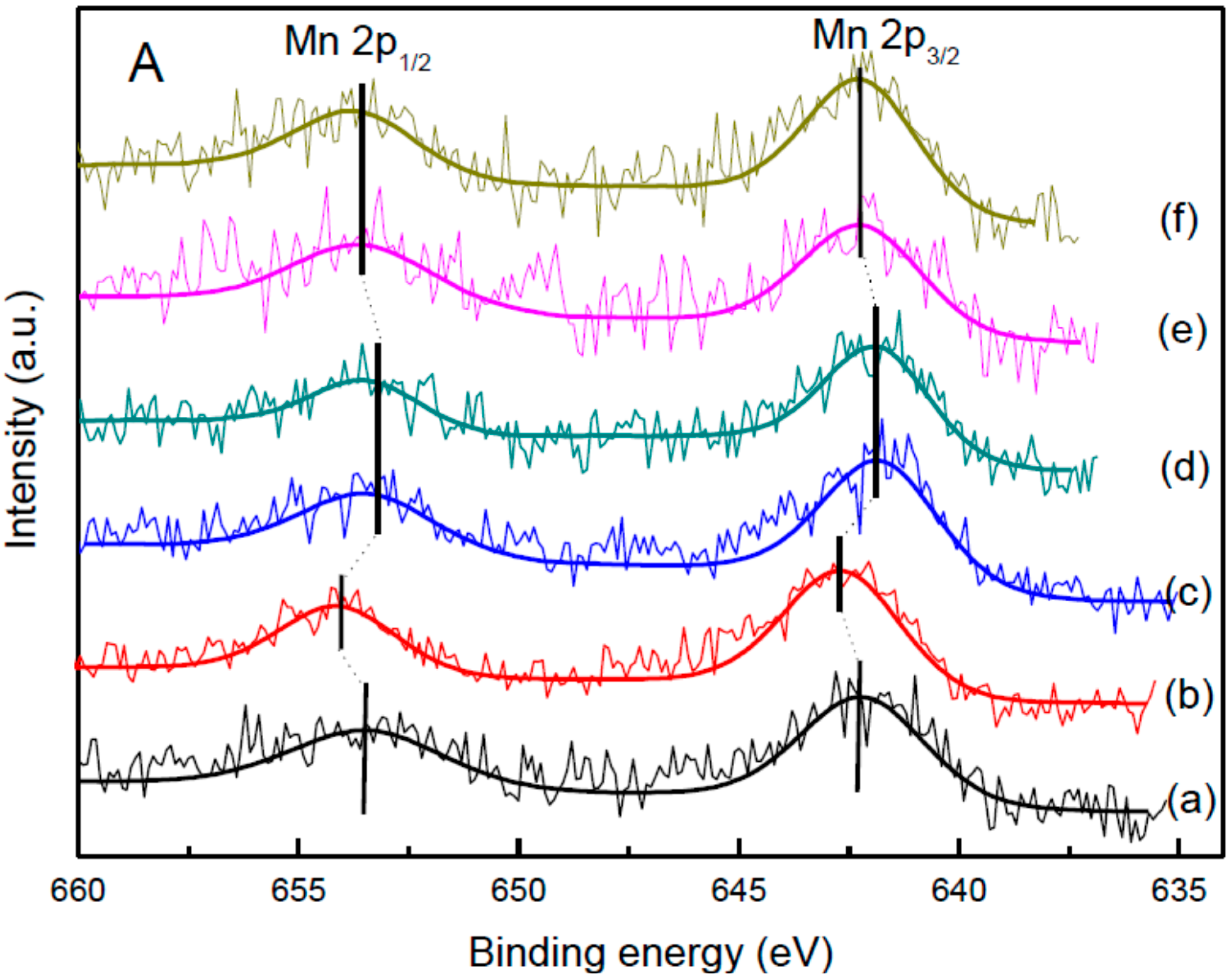

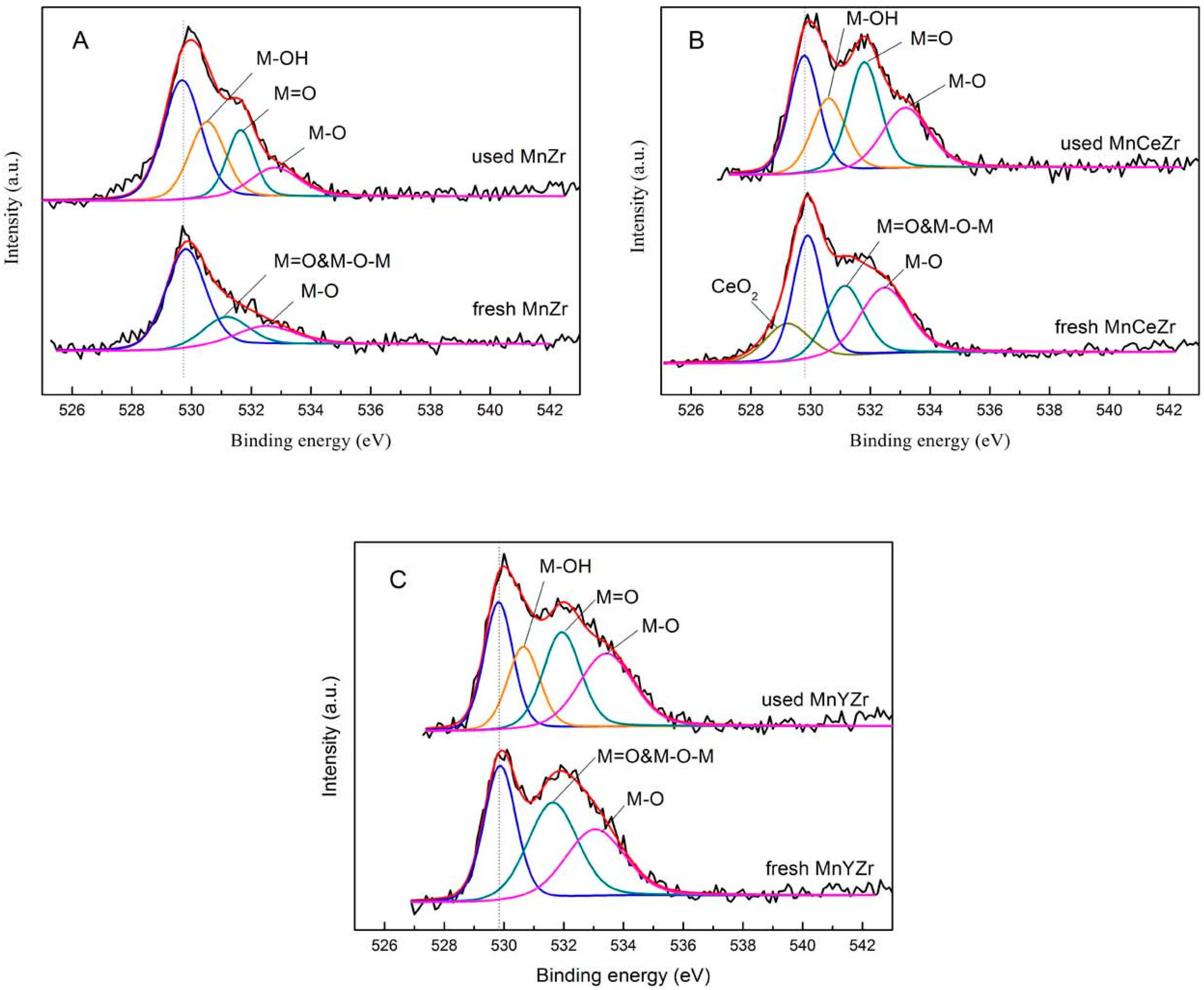

2.7. XPS Results

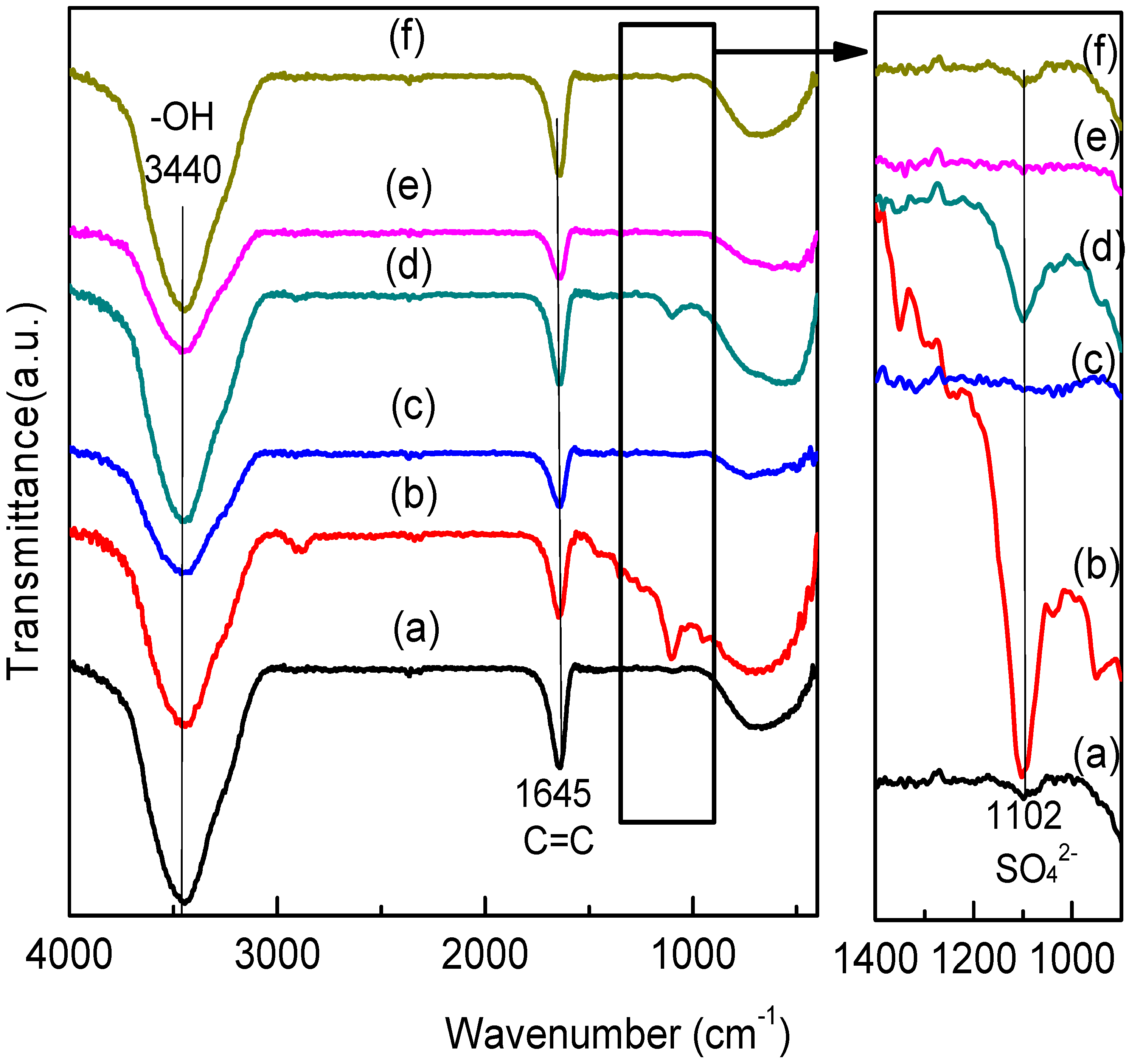

2.8. FTIR Analysis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Pretreatment of MWCNTs

3.2. Preparation of MnOx/ZrO2/MWCNTs

3.3. Preparation of Mn-CeOx(YOx)/ZrO2/MWCNTS

3.4. Catalytic Evaluations

3.5. Catalyst Characterization

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bosch, H.; Jamssen, F. Formation and control of nitrogen oxide. Catal. Today 1988, 2, 369–379. [Google Scholar]

- Nova, I.; Ciardelli, C.; Tronconi, E.; Chatterjee, D.; Bandl-Konrad, B. NH3-NO/NO2 chemistry over V-based catalysts and its role in the mechanism of the Fast SCR reaction. Catal. Today 2006, 114, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giakoumelou, I.; Fountzoula, C.; Kordulis, C.; Boghosian, S. Molecular structure and catalytic activity of V2O5/TiO2 catalysts for the SCR of NO by NH3: In situ Raman spectra in the presence of O2, NH3, NO, H2, H2O, and SO2. J. Catal. 2006, 239, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.Y.; Qiu, F.M.; Yang, H.S.; Tian, W.; Hou, T.F.; Zhang, X.B. Selective catalytic reduction of NOx with ammonia over Mn-Ce-Ox/TiO2-carbon nanotube composites. Catal. Commun. 2011, 12, 1298–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Park, E.D.; Kim, J.M.; Yie, J.E. Manganese oxide catalysts for NOx reduction with NH3 at low temperatures. Appl. Catal. A 2007, 327, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.H.; Tong, Z.Q.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, J.F. Selective catalytic reduction of NO with NH3 at low temperatures over iron and manganese oxides supported on mesoporous silica. Appl. Catal. B 2008, 78, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.H.; Li, X.H.; Gao, X.; Jiang, Y.B.; Lu, Y.X.; Wang, F.R.; Wang, L.F. Selective catalytic reduction of NOx with NH3 on a Cr-Mn mixed oxide at low temperature. Chin. J. Catal. 2009, 30, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.J.; Wang, X.Q.; Qi, G.S.; Wang, J.; Shen, M.Q.; Li, W. Characterization of copper species over Cu/SAPO-34 in selective catalytic reduction of NOx with ammonia: Relationships between active Cu sites and de-NOx performance at low temperature. J. Catal. 2013, 297, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.S.; Huang, B.C.; Su, Y.X.; Zhou, G.Y.; Wang, K.L.; Luo, H.C.; Ye, D.Q. Manganese oxides supported on multi-walled carbon nanotubes for selective catalytic reduction of NO with NH3: Catalytic activity and characterization. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 192, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasel, J.; Kaβner, P.; Montanari, B.; Gazzano, M.; Vaccari, A.; Makowski, W.; Lojewski, T.; Dziembaj, R.; Papp, H. Transition metal oxides supported on active carbons as low temperature catalysts for the selective catalytic reduction (SCR) of NO with NH3. Appl. Catal. B 1998, 18, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.L.; Hao, J.M.; Yi, H.H.; Ning, P. Low-temperature SCR of NO with NH3 on Mn-based Catalysts Modified with Cerium. J. Rare Earths 2007, 25, 240–243. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, B.Q.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Z.B. Low-temperature selective catalytic reduction of NO on MnOx/TiO2 prepared by different methods. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 162, 1249–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smirniotis, P.G.; Pena, D.A.; Uphade, B.S. Low-temperature selective catalytic reduction (SCR) of NO with NH3 by using Mn, Cr, and Cu oxides supported on hombikat TiO2. Ange. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 2479–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, D.K.; Boningari, T.; Boolchand, P.; Smirniotis, P.G. Novel manganese oxide confined interweaved titania nanotubes for the low-temperature Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) of NOx by NH3. J. Catal. 2016, 334, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boningari, T.; Ettireddy, P.R.; Somogyvari, A.; Liu, Y.; Vorontsov, A.; McDonald, C.A.; Smirniotis, P.G. Influence of elevated surface texture hydrated titania on Ce-doped Mn/TiO2 catalysts for the low-temperature SCR of NOx under oxygen-rich conditions. J. Catal. 2015, 325, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettireddy, P.R.; Ettireddy, N.; Boningari, T.; Pardemann, R.; Smirniotis, P.G. Investigation of the selective catalytic reduction of nitric oxide with ammonia over Mn/TiO2 catalysts through transient isotopic labeling and in situ FTIR studies. J. Catal. 2012, 292, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirupathi, B.; Smirniotis, P.G. Nickel-doped Mn/TiO2 as an efficient catalyst for the low-temperature SCR of NO with NH3: Catalytic evaluation and characterizations. J. Catal. 2012, 288, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Huang, R.; Jin, D.; Ye, D. Low temperature SCR of NO with NH3 over carbon nanotubes supported vanadium oxides. Catal. Today 2007, 126, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Miao, L.; Wang, H.; Fu, Q. Highly dispersed Fe2O3 on carbon nanotubes for low-temperature selective catalytic reduction of NO with NH3. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 956–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.B.; Jin, R.B.; Wang, H.Q.; Liu, Y. Effect of ceria doping on SO2 resistance of Mn/TiO2 for selective catalytic reduction of NO with NH3 at low temperature. Catal. Commun. 2009, 10, 935–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, R.B.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Wang, H.B.; Gu, T.T. Relationship between SO2 poisoning effects and reaction temperature for selective catalytic reduction of NO over Mn-Ce/TiO2 catalyst. Catal. Today 2010, 153, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Hou, X.X.; Yang, H.S.; Ma, Z.X.; Zheng, J.W.; Liu, F.; Zhang, X.B.; Yuan, Z.Y. Promotional effect of CeOx for NO reduction over V2O5/TiO2-carbon nanotube composites. J. Mol. Catal. A 2012, 356, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.X.; Yang, H.S.; Li, B.; Liu, F.; Zhang, X.B. Temperature-Dependent Effects of SO2 on Selective Catalytic Reduction of NO over Fe-Cu-Ox/CNTs-TiO2 Catalysts. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 3708–3713. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, S.W.; Luo, H.C.; Li, L.; Wei, Z.; Huang, B.C. H2O and SO2 deactivation mechanism of MnOx/MWCNTs for low-temperature SCR of NOx with NH3. J. Mol. Catal. A 2013, 377, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.S.; Zhang, L.; Shi, L.Y.; Fang, C.; Li, H.R.; Gao, R.H.; Huang, L.; Zhang, J.P. In situ supported MnOx-CeOx on carbon nanotubes for the low-temperature selective catalytic reduction of NO with NH3. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 1127–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, D.; Liu, Y.; Kamasamudram, K.; Li, J.H.; Epling, W. SO2 poisoning impact on the NH3-SCR reaction over a commercial Cu-SAPO-34 SCR catalyst. Appl. Catal. B 2014, 156–157, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busca, G.; Lietti, L.; Ramis, G.; Berti, F. Chemical and mechanistic aspects of the selective catalytic reduction of NOx by ammonia over oxide catalysts: A review. Appl. Catal. B 1998, 18, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirupathi, B.; Smirniotis, P.G. Co-doping a metal (Cr, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn, Ce, and Zr) on Mn/TiO2 catalyst and its effect on the selective reduction of NO with NH3 at low-temperatures. Appl. Catal. B 2011, 110, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.W. The thermal decomposition temperature of Sulphate of atomic steady potential scale. Chin. J. Chem. Rev. 1986, 11, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ettireddy, P.R.; Ettireddy, N.; Mamedov, S.; Boolchand, P.; Smirniotis, G.P. Surface characterization studies of TiO2 supported manganese oxide catalysts for low temperature SCR of NO with NH3. Appl. Catal. B 2007, 76, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, L.S.; Pan, S.W.; Wei, Z.L.; Huang, B.C. Effects of cerium on the selective catalytic reduction activity and structural properties of manganese oxides supported on multi-walled carbon nanotubes catalysts. Chin. J. Catal. 2013, 34, 1087–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koc, S.N.; Gurdag, G.; Geissler, S.; Muhler, M. Effect of nickel, lanthanum, and yttrium addition to magnesium molybdate catalyst on the catalytic activity for oxidative dehydrogenation of propane. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2004, 43, 2376–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.S.; Zhang, L.; Fang, C.; Gao, R.H.; Qian, Y.L.; Shi, L.Y.; Zhang, J.P. MnOx-CeOx/CNTs pyridine-thermally prepared via a novel in situ deposition strategy for selective catalytic reduction of NO with NH3. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 8811–8819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.C.; Huang, B.C.; Fu, M.L.; Wu, J.L.; Ye, D.Q. SO2 Deactivation Mechanism of MnOx /MWCNTs Catalyst for Low-Temperature Selective Catalytic Reduction of NOx by Ammonia. Acta Phys. Chim. Sin. 2012, 28, 2175–2182. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.Z.; Chen, X.Y.; Li, J.H.; Ma, L.; Wang, C.Z.; Liu, C.X.; Schwank, J.W.; Hao, J.M. Improvement of Activity and SO2 Tolerance of Sn-Modified MnOx-CeO2 Catalysts for NH3-SCR at Low Temperatures. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 5294–5301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, B.; Lin, H.; Zhu, L.; Huang, Z. Selective Catalytic Reduction of NOx with NH3 over Mn, Ce Substitution Ti0.9V0.1O2-δ Nanocomposites Catalysts Prepared by Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis Method. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 12850–12863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, R.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Wang, H.; Gu, T. Low-temperature selective catalytic reduction of NO with NH3 over Mn Ce oxides supported on TiO2 and Al2O3: A comparative study. Chemosphere 2010, 78, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupin, J.C.; Gonbeau, D.; Vinatier, P.; Levasseur, A. Systematic XPS studies of metal oxides, hydroxides and peroxides. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2000, 2, 1319–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, M.; Chopra, N.; Hinds, B.J. Effect of tip functionalization on transport through vertically oriented carbon nanotube membranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 9062–9070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.Q.; Gao, L. A study of the electrical properties of carbon nanotube-NiFe2O4 composites: Effect of the surface treatment of the carbon nanotubes. Carbon 2005, 43, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.L.; Wang, L.S.; Huang, B.C. In situ DRIFTS study of the low temperature selective catalytic reduction of NO with NH3 over MnOx supported on multi-walled carbon nanotubes catalysts. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2015, 15, 1017–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.Q.; Rochette, J.F.; Sacher, E. Spectroscopic evidence for π-π interaction between poly(diallyl dimethylammonium) chloride and multiwalled carbon nanotubes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 4481–4484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Jiang, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.J.; Song, D.; Li, F.S. Synthesis of Fe3O4/CNTs magnetic nanocomposites at the liquid-liquid interface using oleate as surfactant and reactant. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2009, 321, 408–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Cheng, J.P.; Liu, F.; Zhang, X.B. Controlling the size and size distribution of magnetite nanoparticles on carbon nanotubes. J. Alloys Comp. 2010, 502, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.X.; Zhang, X.P.; Ma, H.Q.; Yao, Y.; Liu, T. A comparative study of Mn/CeO2, Mn/ZrO2 and Mn/Ce-ZrO2 for low temperature selective catalytic reduction of NO with NH3 in the presence of SO2 and H2O. J. Environ. Sci. 2013, 25, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, R.B.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cen, W.L.; Wu, Z.B.; Wang, H.Q.; Weng, X.L. The role of cerium in the improved SO2 tolerance for NO reduction with NH3 over Mn-Ce/TiO2 catalyst at low temperature. Appl. Catal. B 2014, 148–149, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Liu, X.Q.; Huang, B.C.; Wu, Y.M. Structural properties and low-temperature SCR activity of zirconium-modified MnOx/MWCNTs catalysts. Acta Phys. Chim. Sin. 2014, 30, 1895–1902. [Google Scholar]

| Catalyst | Surface Atomic Concentration (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | O | Mn | Zr | Ce | Y | S | N | |

| Fresh MnZr | 88.25 | 8.14 | 1.6 | 2.01 | - | - | - | - |

| Fresh MnCeZr | 86.98 | 9.22 | 1.32 | 1.72 | 0.76 | - | - | - |

| Fresh MnYZr | 89.91 | 7.23 | 0.75 | 1.89 | - | 0.22 | - | - |

| Used MnZr | 88.82 | 7.54 | 1.38 | 1.61 | - | - | 0.14 | 0.51 |

| Used MnCeZr | 88.66 | 7.78 | 1.09 | 1.56 | 0.52 | - | 0.15 | - |

| Used MnYZr | 88.53 | 7.71 | 0.71 | 1.66 | - | 0.18 | 0.14 | 1.07 |

| Catalyst | O 1s 1 | O 1s 2 | O 1s 3 | O 1s 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MnZr | 0.62 | 0.21 | 0.17 | - |

| MnZr-SO2 | 0.43 | 0.26 | 0.18 | 0.13 |

| MnCeZr | 0.15 | 0.32 | 0.24 | 0.29 |

| MnCeZr-SO2 | 0.29 | 0.20 | 0.28 | 0.23 |

| MnYZr | 0.33 | 0.36 | 0.30 | - |

| MnYZr-SO2 | 0.27 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 0.28 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dong, L.; Fan, Y.; Ling, W.; Yang, C.; Huang, B. Effect of Ce/Y Addition on Low-Temperature SCR Activity and SO2 and H2O Resistance of MnOx/ZrO2/MWCNTs Catalysts. Catalysts 2017, 7, 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal7060181

Dong L, Fan Y, Ling W, Yang C, Huang B. Effect of Ce/Y Addition on Low-Temperature SCR Activity and SO2 and H2O Resistance of MnOx/ZrO2/MWCNTs Catalysts. Catalysts. 2017; 7(6):181. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal7060181

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Lifu, Yinming Fan, Wei Ling, Chao Yang, and Bichun Huang. 2017. "Effect of Ce/Y Addition on Low-Temperature SCR Activity and SO2 and H2O Resistance of MnOx/ZrO2/MWCNTs Catalysts" Catalysts 7, no. 6: 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal7060181