Neuropilins: A New Target for Cancer Therapy

Abstract

: Recent investigations highlighted strong similarities between neural crest migration during embryogenesis and metastatic processes. Indeed, some families of axon guidance molecules were also reported to participate in cancer invasion: plexins/semaphorins/neuropilins, ephrins/Eph receptors, netrin/DCC/UNC5. Neuropilins (NRPs) are transmembrane non tyrosine-kinase glycoproteins first identified as receptors for class-3 semaphorins. They are particularly involved in neural crest migration and axonal growth during development of the nervous system. Since many types of tumor and endothelial cells express NRP receptors, various soluble molecules were also found to interact with these receptors to modulate cancer progression. Among them, angiogenic factors belonging to the Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) family seem to be responsible for NRP-related angiogenesis. Because NRPs expression is often upregulated in cancer tissues and correlated with poor prognosis, NRPs expression might be considered as a prognostic factor. While NRP1 was intensively studied for many years and identified as an attractive angiogenesis target for cancer therapy, the NRP2 signaling pathway has just recently been studied. Although NRP genes share 44% homology, differences in their expression patterns, ligands specificities and signaling pathways were observed. Indeed, NRP2 may regulate tumor progression by several concurrent mechanisms, not only angiogenesis but lymphangiogenesis, epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis. In view of their multiples functions in cancer promotion, NRPs fulfill all the criteria of a therapeutic target for innovative anti-tumor therapies. This review focuses on NRP-specific roles in tumor progression.1. Introduction

Neuropilins (NRPs; previously known as A5 protein) were first identified by Takagi et al. in 1987 by immunofluorescent staining of frozen sections of Xenopus tadpole nervous system [1]. This glycoprotein of 130–140 kDa, highly conserved among vertebrates, was then isolated in the nervous developing system of a broad spectrum of animal species, such as chicken [2,3], mice [4], and rats [5,6]. While NRP1 was the first member of the NRP family to be described, NRP2 was rapidly isolated by Chen et al. in 1997, by RT-PCR and gene transfer [7].

A major distinction between these two members of the NRP family is based on their ligand specificities. NRPs were originally described as high-affinity cell-surface receptors for axon guidance molecules such as class-3 semaphorins (Sema) [6]. Indeed, NRP1 is a receptor for semaphorin-3A, 3C, 3F [5,6] while NRP2 preferentially binds Semaphorin 3B, 3C, 3D, 3F [7,8] (Figure 1).

Several analyses using mutant mice lacking NRPs function subsequently conferred to semaphorin/neuropilin an essential role in axon guidance during nervous system development [8-11].

In vivo models using NRPs transgenes also suggested other essential functions of NRPs. Indeed, overexpression of NRP1 in chimeric mice generated an excess of capillaries and blood vessels, suggesting an important role of NRP1 in angiogenesis and vasculogenesis [12]. In contrast, NRP1 null-mutant embryos showed severe types of vascular defects, especially in neuronal vasculature, yolk sac vessel network organization, aortic arch development [13] and in the cardiovascular system, resulting in death of homozygous embryos at E12.5 to E13.5 [13,14]. NRP2 knock-out mice are viable suggesting that NRP2 is not essential for vascular development, unlike NRP1 [9,11]. Moreover, NRP2 homozygous mutant mice are characterized by abnormal lymphatic and capillary development suggesting a selective requirement for NRP2 in the formation of lymphatic vessels [15]. However, double knock-out of NRPs genes (NRP1−/− NRP2−/−) constitutes the most severe phenotype observed, impairing any blood vessel development and causing earliest death in utero at E8.5 [14].

Because Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) plays a central role in the development of vascular network, interactions between NRPs and VEGF were rapidly considered. NRPs were indeed found to be receptors for several members of the VEGF family. NRP1 can effectively bind VEGF165, PIGF-2 (Placenta Growth Factor), VEGF-B, VEGF-C, VEGF-D and VEGF-E [16-21], whereas NRP2 is a receptor for VEGF145, VEGF165, PIGF-2 [18,22], VEGF-C [20,22], and VEGF-D [20]. NRPs are also reported to bind diverse heparin-growth factors, such as FGF (Fibroblast Growth Factor) and HGF (Hepatocyte Growth Factor) [23,24] (Figure 1).

2. NRPs: Structural Particularities

In humans, NRP1 and NRP2 genes map to two different chromosomes: Chromosomes 10p12 and 2q34, respectively [25]. Although NRPs share only 44% homology in their amino acid sequences, some similarities to known proteins can be observed in their structure. NRPs are composed of an extracellular domain, transmembrane domain and a short intracellular domain. Indeed, the extracellular domain is composed of two Complement Binding motifs (CUB), homologous to the C1r and C1s complement components (named domains a1 and a2), two domains b1 and b2 homologous to the coagulation factors V and VIII and one third domain, c, homologous to the meprim domain sharing a tyrosine phosphatase activity μ [4,26]. a1/a2 domains are responsible for semaphorin binding, whereas b1/b2 are suggested for both VEGF and semaphorin binding. c-domain is involved in dimerization of the receptor [8] (Figure 1). Because NRPs have a short intracellular domain of only 40 amino acids, it was assumed that they cannot transmit any signal on their own.

2.1. Isoforms

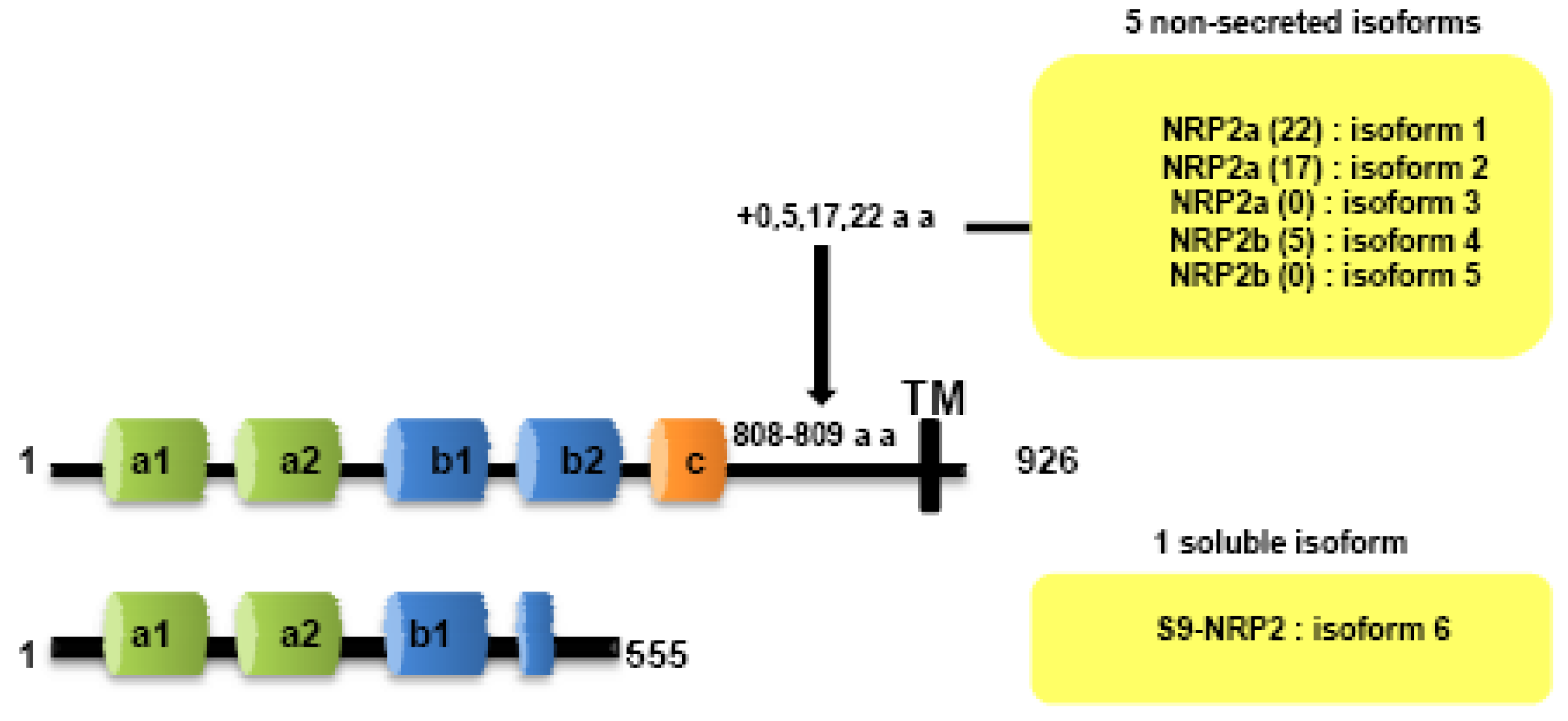

Both NRPs genes are composed of 17 exons. Contrary to NRP1, NRP2 is expressed as several alternatively spliced forms. In particularly, two isoforms of NRP2, NRP2a and NRP2b, that arise by alternative splicing, have been described subsequently in mouse [7] and humans [25]. Divergences between NRP2a and NRP2b are principally observed in the linker between transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains. NRP2 subisoforms were subsequently described by Chen [7] and Rossignol [25]. Insertions of 17 or 22 amino acids after amino acid 809 are described for NRP2a (NRP2a (17), NRP2a(22)) whereas NRP2b is characterized by insertions of 0 or 5 amino acids after amino acid 808 (NRP2b(0), NRP2b(5)) (Figure 2). NRP2a seems to be closer to NRP1 (44% homology) than NRP2b (11%) [25].

2.2. Soluble Forms

Two soluble forms of NRP1 (s11NRP1 and s12NRP1) and one of NRP2 (s9NRP2) were cloned by Rossignol and collaborators [25]. Later, two novel soluble forms of NRP1, sIIINRP1 and sIVNRPI were characterized [27]. While these soluble isoforms have conserved their extracellular domains responsible for ligand binding, c-domain, transmembrane and intracellular domains were lacking. Moreover, Gagnon et al., reported that s11NRP1 is capable of tumor cell apoptosis by antagonizing VEGF binding, suggesting that sNRPs and NRPs have opposite functions [28].

3. Neuropilins Expression Pattern

3.1. Embryogenesis

First reports limited NRPs expression in the nervous developing tissues [1,2,4,7,29]. Indeed, Chen et al. observed increased NRP2 expression in most components of the developing nervous system including spinal cord, sympathetic ganglia, olfactory system, neocortex, hippocamp [7].

NRP were also found in development of many non neuronal tissues such as bones, several muscles, intestinal epithelium, kidney, lung, dorsal aorta [7]. Moreover, knock-out studies have suggested an important role of the NRPs in the development of the vascular system during embryogenesis. While NRP1 is preferentially expressed in arteries during embryonic development, NRP2 is required for the formation of veins and lymphatic vessels [12,15].

3.2. Immune System

NRP1 was rapidly identified on various immune cells such as some subpopulations of T lymphocytes and on dendritic cells (DC) in vitro and in vivo [30]. In this immune context, NRP1 enhances cell-cell interaction, especially in mediating DC-induced proliferation of resting T cells [30]. NRP1 is expressed by CD4+CD25+ murine regulatory T cells but not by naive T cells [31]. When expressed on murine T reg cells, NRP1 inhibits T cell proliferation [32]. However, Milpied et al. observed in 2009 that NRP1 expression on murine T reg could not be extended in human [33]. On the other hand, NRP2's contribution in the immune system was only very recently studied. NRP2 is expressed on a polysialylated form on mature human DC [34]. Because polysialylation of proteins is a very rare phenomenon, its role has not been extensively characterized. However, polysialylation of NRP2 on DC seems to be essential for CCL21-dependent DC migration (CCL21: Chemokine C-C motif Ligand 21) to the lymph nodes during immune response [35,36].

3.3. Human Tumors

The contribution of NRPs in angiogenesis prompted the investigation of NRP's role in oncogenesis. Besides the presence of NRPs on tumor-associated vessels, authors have reported the wide expression of NRPs among different human tumors, suggesting a potential role of this molecular network in cancer progression. In 1998, Soker et al. isolated NRP1 from endothelial cells and tumor tissues [21]. Indeed, NRPs expression is not restricted in intra-tumoral vessels, but a large variety of cancer cells are reported to express one or both NRPs. Moreover, NRPs are often the only VEGF-receptors expressed by tumor cells [37,38], conferring an essential role of these glycoproteins as growth factor receptors. Although NRP1 is expressed by a large variety of tumors, even less is known concerning the expression of NRP2 (Table 1). However, NRP2 expression was found in osteosarcomas [39], melanomas [40], lung cancers [41,42], brain tumors [43,44] colon cancers [45], pancreatic cancers [46-49], breast cancers [50], myeloid leukemias [51], salivary adenoid cystic carcinomas (SACCs) [52], infantile hemangiomas [53], ovarian neoplasms [54] and bladder cancers [55] (Table 1).

3.4. Regulation of Neuropilins Expression

NRP1 expression was promoted by hypoxia in several models [78-80] and by ischemia in rats [81], and in mice [82]. Moreover, several growth factors and inflammatory cytokines are involved in NRP regulation too: In pancreatic cancer cells, IL-6 enhances NRP1 expression [60] whereas IL-8 increases NRP2 expression via activation of ERK1/2 pathway [83]. TNFα was shown to upregulate VEGFR2 and NRP1 in human vascular endothelial cells [84]. While TGF-β1 and IL-1β inhibit NRP1 expression, TGF-β1 stimulates NRP2 expression in human proximal tubular cells through activation of MEK1/2-ERK1/2 pathway [85]. Oncostatin M activates both NRP1 and NRP2 expression [85].

4. Neuropilins Role in Oncogenesis

NRPs display a short intracytoplasmic tail of 40 amino acids which does not contain any kinase domain, leading to the suggestion that neuropilins can not directly transmit intracellular signals. This led to the proposal that hetero-dimerization with other membrane receptors are required to mediate neuropilin-downstream signaling.

4.1. Interactions with Plexins/Semaphorins

Semaphorins (Sema, also known as collapsins) are subdivided into eight classes, on the basis of structural similarities. Class 1 and 2 constitutes invertebrate semaphorins, whereas classes 3 to 7 comprise vertebrate semaphorins [86]. All semaphorins are characterized by an identical N-terminal 500-amino-acid-long sema domain, which is essential for semaphorin signaling. The structure of the sema domain is a seven-blade β-propeller fold which presented similarities with extracellular domain of α-integrins [87]. Next to the sema domain, semaphorins contain several distinct domains in their structure, such as a plexin-semaphorin-integrin domain (PSI), an immunoglobulin-like, a thrombospondin and a basic-C domains [88]. Class-3 semaphorins are secreted semaphorins characterized by a basic-charged domain at the C-terminus. Class 4–7 semaphorins are membrane-bound semaphorins which are characterized by thrombospondin repeats (class-5 semaphorins) or glycophosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor (class-7 semaphorins). Membrane-bound semaphorins can be cleaved into soluble forms through proteolytic degradation [89]. Two high affinity receptors have been identified for semaphorins: Plexins and Neuropilins. Various studies indicate that plexins are required for class 3 semaphorin/neuropilins signaling pathway during both embryonic development and tumorigenesis.

Plexin family is the first class of co-receptor identified. Plexins have been identified like NRPs, from immunostaining of Xenopus tadpoles nervous tissue [1]. While plexins play an important role in axon guidance [90] by forming complexes with NRPs [91,92], plexins have been identified on various tumor tissues, suggesting a role in tumorigenesis [93,94]. Nine members of the plexin family have been identified, subdivided into four subfamilies comprising four type-A plexins, three type-B plexins, plexin C1 and plexin D1. Plexins can tranduce intracellular signals through activation of Rho-like GTPases, such as Rnd1 for plexin A1 and Rac1 for plexin B1 [95-97]. Moreover, type B plexins contain a binding site for a PDZ domain in the C-terminal domain [98-100]. The extracellular domains of all plexins are characterized by the presence of a sema domain, and by the presence of PSI and glycine-proline (G-P)-rich motifs [86]. Membrane-bound semaphorins can directly bind to the plexins, whereas secreted semaphorins such as class-3 semaphorins required NRPs as co-receptor to mediate the signal [86].

Like type-B plexins, NRPs contain a binding site for PDZ domains in the C-terminal domain. Indeed, the PDZ domain of NIP, also called GIPC (GAIP interacting protein at the C terminus), is thought to be implicated in interaction with NRPs and plexins, activating small GTPase-activating proteins [101]. In particular, the last three amino-acids SEA of the C-terminal sequence of NRPs seem to be responsible for interaction with G-interacting proteins [101] (Figure 3).

Semaphorins are reported to be very often down-regulated or mutated in human cancers, allowing massive VEGF/NRPs interactions. Because semaphorins are frequently inactivated by allele loss or promoter methylation, they have been rapidly considered to function as a TSG (tumor suppressor gene). Indeed, deletions occur in the region 3p21.3 of the short arm of chromosome 3, a region encoding for Sema3B and Sema3F in various cancers, including lung cancer and even ovarian cancer [102-104]. Moreover, semaphorin promoter hypermethylation and various mutations occur in lung and breast cancers [42,105-108].

4.1.1. Semaphorin 3A

First, Bagnard et al. reported that Semaphorin 3A (Sema3A) mediates cell repulsion and can even induce cell death in a neuroectodermal progenitor cell line, both effects depending on interactions with NRP1 [109].When Sema3A is added to the culture medium of Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVEC) cells for 48 h with VEGF165, cell survival decreases. NRP1 is implicated in this Sema3A-mediated apoptosis [110]. Moreover, Sema3A has been implicated directly in Fas-mediated apoptosis in a recent study [111]. After a stimulation of leukemic T cells by Sema3A, Fas localizes into the lipid rafts and sensitizes these T cells to FasL-mediated apoptosis [111] (Table 2).

In another study, Kigel and colleagues transfected breast cancer cells expressing NRP1 and-or NRP2 with each semaphorin to analyze their role in tumor progression in xenograft experiments [112]. Sema3A, sema3D, sema3E and sema3G overexpression in breast cancer cells significantly inhibits the development of tumor in xenograft models and decreases the number of intra-tumor blood vessels, suggesting an anti-angiogenic role of these molecules [112]. In this model, the anti-tumor effect of each of the semaphorins correlated very well with the expression of the related receptor on tumor cells [112]. Furthermore, in a very recent study using multiple murine models of tumorigenesis, Maione and collaborators showed that inhibition of sema3A in the later stages of carcinogenesis is responsible for enhanced angiogenesis and tumor progression [113]. By contrast, restoration of Sema3A expression in these cells normalizes intra-tumor vasculature, indicating that Sema3A could be used as a potential anti-angiogenic agent [113]. In another recent study, Sema3A role in tumor progression and in tumor angiogenesis was evaluated using three experimental approaches, using different systems for the release of the semaphorins [114]. In all experiments, NRP1 seems to be essential for Sema3 A-mediated inhibition of tumor growth, angiogenesis and metastasis [114] (Table 2).

4.1.2. Semaphorin 3B

In lung and ovarian cancer cells, Semaphorin 3B (Sema3B) expression decreases colony formation, proliferation, and even tumorigenicity in murine xenograft experiments [42,115]. Similarly, Sema3B was shown to induce apoptosis in cancer cells, in particularly by blocking VEGF-binding to the NRPs [116,117] (Table 2). Moreover, NRP1-Sema3B interactions induce high level of IL-8 in tumor cells, leading to a massive monocyte/macrophage recruitment, promoting invasion and metastasis formation [118]. As a consequence, when sema3B is inhibited using RNA interference and IL-8 neutralized with blocking monoclonal antibodies, a decrease of invasion and metastasis is observed in murine xenograft experiments [118] (Table 2).

4.1.3. Semaphorin 3F

First observations that Semaphorin 3F (Sema3F) might have a role in cell motility and cell invasion was suggested by Brambilla and colleagues, in lung cancer cells [119]. Then, some studies reported that Sema3F can even induce apoptosis in cancer cells as well as tumor suppression in various xenograft experiments. Indeed, transfection of Sema3F in the murine fibrosarcoma cell line A9 and in HEY ovarian cell line suppresses tumor formation in nude mice, whereas no effect was observed after transfection of Sema3F in the small cell lung cancer cell line GLC45 [120]. When nude rats were orthotopically implanted with lung cancer cells transfected or not with Sema3F gene, all animals injected with cells expressing sema3f survived to 100 days whereas all the other rats died [121] (Table 2).

A role of Sema3F in tumor angiogenesis was then suggested. Implantation of BHK-21 (Baby Hamster Kidney-21) cells transfected with Sema3F concomitantly with cells producing VEGF-165 inhibited tumor-related angiogenesis in mice whereas no effect on angiogenesis was observed when BHK-21 cells transfected with empty vector were implanted with the same VEGF-165 producing cells [122]. Moreover, Sema3F transfection in the renal cell line HEK293 induced smaller tumors and a poorly-vascularized phenotype in xenograft experiments [122]. As a consequence, Sema3F and VEGF were rapidly considered to generate opposite activities. In fact, in highly metastatic melanoma cells, Sema3F completely inhibits metastasis in vivo and decreased the number of intra-tumor vessels, suggesting that Sema3F has huge potential in anti-angiogenic and anti-metastasis therapies [123] (Table 2). In addition, Sema3F can represent a powerful inhibitor of melanoma cell proliferation through its relation with NRP receptors [124].

Moreover, Sema3F blocks cell attachment and spreading in MCF7 and C100 breast cell lines, this effect depending on its interactions either with NRP1 or NRP2 [125] (Table 2).

4.1.4. Semaphorin 3E

Although most class 3 semaphorins are considered to be TSG, it appears that others support opposite activities. Indeed, Semaphorin 3E (Sema3E) is described as an enhancer of tumor growth and metastasis in vitro and in vivo in xenograft experiments using breast cancer cells [126] (Table 2).

4.2. Cooperation with Growth Factor Receptors

4.2.1. VEGFRs

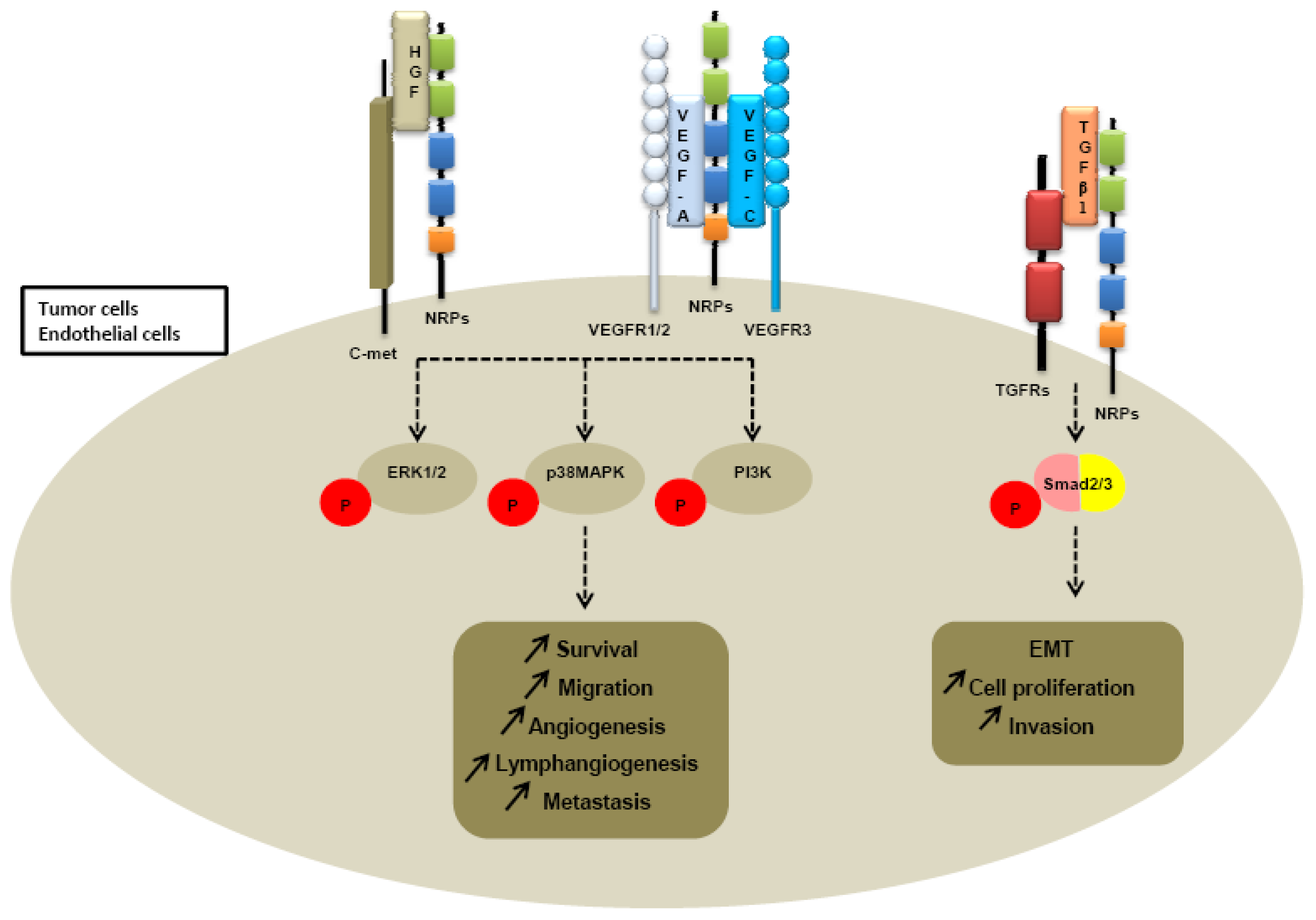

Further investigations of neuropilin-dependent molecular pathways suggested that neuropilins contribute to tumor growth and angiogenesis through their cooperation with both VEGFR receptors, VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 (Figure 4).

First, Soker et al. reported that coexpression of NRP1 and VEGFR2 on porcine aortic endothelial cells enhances at least four-times the VEGF binding to VEGFR2 and in this way modulates downstream signaling and biological responses [21]. Later, Biacore analysis revealed that NRP1 interacts with both VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 [19]. Moreover, NRP1 enhances binding of VEGF to these two high affinity receptors. Similar results were obtained for NRP2. Indeed, co-immunoprecipitation studies revealed that NRP2 and VEGFR1 associate with each other to tranduce intracellular signals [129]. NRP2 enhances VEGFR1 phosphorylation and subsequently activates multiple intracellular pathways like extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) or phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathways in colorectal cancer cells and pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells [45,46]. (Table 3) While NRP1 implication in the angiogenesis process has now considerable evidence, NRP2 appears to regulate lymphangiogenesis and metastatic processes. Indeed, NRP2 homozygous mutant mice are characterized by abnormal lymphatic and capillaries development proposing a selective requirement for NRP2 in the formation of lymphatic vessels [15]. Karpänen et al. propose that NRP2 contributes to lymphangiogenesis and metastastatic processes through direct interactions with VEGF-C, VEGF-D and VEGFR3 [20]. NRP2 increases VEGF-A and VEGF-C-induced survival and migration of endothelial cells [130]. Moreover, Caunt et al. recently reported that NRP2 blocking with a monoclonal antibody (anti-NRP2B) leads to a reduction of VEGFC-mediated migration of Lymphatic Endothelial cells (LEC) in vitro and to an inhibition of lymphangiogenesis in vivo [131]. Metastasis formation is found to be subsequently reduced in mice in xenograft models after anti-NRP2B treatment [131]. Double-heterozygous nrp2+/−vegfr2+/− mice have normal lymphatic development unlike double-heterozygous nrp2+/−vegfr3+/− mice, indicating that Nrp2 partners with VEGFR3 to modulate lymphatic vessel sprouting and lymphangiogenesis [132]. Finally, another recently published study has reinforced the essential role of NRP2 in lymphangiogenesis process. Indeed, NRP2 knockdown by RNA interference improves corneal graft survival by suppressing lymphangiogenesis in vascular beds in a murine model of corneal transplantation [133] (Table 3).

4.2.2. Integrins

Integrins have important roles in cell attachment, survival, migration, invasion and angiogenesis, which are all critical for carcinogenesis. Many integrins have been implicated in cancer progression. Indeed, Fukasawa and colleagues show that NRP1 interacts with integrin-β1 in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and in this way promotes tumor cell growth, survival and invasion [134]. NRP1 was suggested to interact with α5β1 integrin to regulate angiogenesis in endothelial cells [135]. In lung cancer cells, anti-tumor effect of Sema3F is associated with loss of activated α5β3 integrin [121]. However, some integrins can support opposite activities. For example, in breast tumor cells, Sema3A treatment reduces cell migration in increasing α2β1 integrin level [127]. In endothelial cells, β3 integrin inhibits VEGF-mediated angiogenesis by sequestering NRP1 and preventing it from interacting with VEGFR2 [136].

4.2.3. c-met

Because heparin growth factors FGF and HGF have been recently identified as NRPs ligands, they are believed to contribute to NRP-mediated angiogenesis too. Indeed, NRP1 potentiates HGF and FGF2 induced proliferation, survival, invasion in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC), glioma cells, pancreatic cancer cells [23,137,138]. It appears that NRPs can be a receptor for HGF but can also enhance c-met phosphorylation by activating the c-met receptor itself. Indeed, co-immunoprecipitation studies confirm that NRPs interact directly with c-met receptor [138] (Table 3). Sulpice et al. confirmed in 2008 that both NRPs participate to VEGF and HGF linked-angiogenic activity in endothelial cells through enhancing autocrine hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)/scatter factor (SF)/c-Met signaling [24,137]. NRPs generate activation of several signaling pathways through c-met interaction, including p38-mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38-MAPK), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), src, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) [24,137,138] (Figure 4).

4.2.4. TGFRs

More recently, a study suggested that NRP1 is a receptor for both active TGFβ1 and TGFβ1-LAP. In addition, NRP1-TGFβ1 interactions on T cells resulted in enhanced T regulator activity [139]. Then other reports confirmed that NRP1 promotes TGFβ1 signaling pathway. Indeed, in a recent study, Glinka et al. show that NRP1 associates with TGFRI and TGFRII to enhance TGFβ1 signaling in cancer cells [140] (Table 3). Moreover, NRP1 was shown to confer a myofibroblast phenotype by enhancing PDGF/TGFβ1 pathways in hepatic human cells [141] and in stromal fibroblasts [142]. Because NRPs are not tyrosine-kinase receptors, NRP1 was thought to cooperate with TGFRs to transduce the signal [142]. A similar role was attributed to NRP2. Indeed, we noticed that NRP2 expression enhances TGFβ1 signaling leading to constitutive Smad2/3 phosphorylation in colorectal cancer cells [143]. Biacore analysis revealed that NRP2, like NRP1, is a receptor for active TGFβ1 [143]. Moreover, NRP2 confered a fibroblastic-like shape to cancer cells, suggesting an involvement of neuropilin-2 in epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) [143] (Table 3). EMT is indeed characterized by a breakdown of cell junctions and the loss of epithelial characteristics and cell polarity, contributing to carcinoma progression. Besides the gain of mesenchymal markers, EMT endows cancer cells for migration, invasiveness and subsequent metastasis formation [144]. Indeed, the presence of neuropilin-2 in colorectal carcinoma cell lines is correlated with loss of epithelial markers such as cytokeratin-20 and E-cadherin and with acquisition of mesenchymal molecules such as vimentin [143].

In view of its implication in multiple processes such as angiogenesis, lymphangiogenesis, EMT, and metastasis, NRP2 fulfills all the criteria of a therapeutic target to disrupt multiple oncogenic functions in solid tumors.

5. Neuropilins: A Surrogate Marker for Cancer Progression

Because NRP2 is implicated in multiple processes including angiogenesis, lymphangiogenesis and metastasis, it became rapidly apparent that NRP2 detection constitutes a novel diagnostic and prognostic tool in a great majority of tumors.

NRP2 expression is correlated twith increased vascularity and poor prognosis in osteosarcomas [39] and non small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) [41]. Nrp2 was also detected in salivary adenoid cystic carcinomas (SACCs), and its expression level significantly correlated with microvessel density, tumor size, clinical stage, vascular invasion, and metastasis of SACCs [54]. In breast cancers, NRP2 expression is significantly correlated with lymph node metastasis, VEGF-C expression and cytoplasmic CXCR4 expression [50]. NRP2 expression is significantly upregulated in early and advanced stages of neuroblastomas [44]. Moreover, NRP2 is expressed by a vast majority of endocrines pancreatic tumors, suggesting that NRP2 can be used as a diagnostic marker for these tumors [47]. NRP2 was shown to be also a biomarker of potential clinical significance associated with bladder cancer progression [55].

6. Neuropilins Targeting

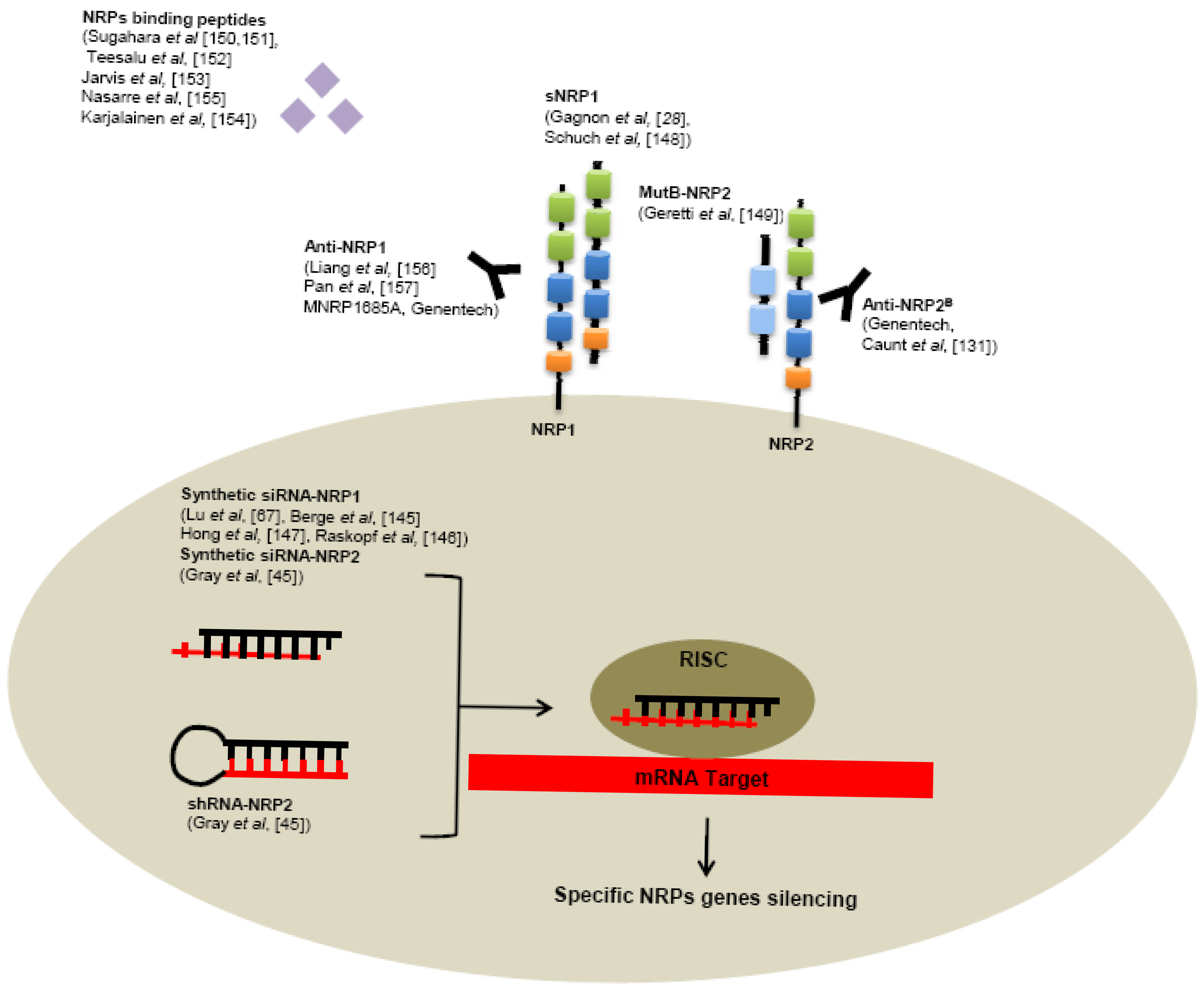

Several tools have been developed to neutralize NRPs receptors, targeting NRPs genes like RNA interference or receptors using specific monoclonal antibodies or small peptides (Figure 5).

6.1. RNA Interference

Use of siRNA targeting NRP1 significantly reduces tumor growth, angiogenesis, metastasis formation in various human cancer models, such as hepatocellular carcinoma [145,146], acute myeloid leukemia [67], lung cancer [147]. Also reduction of NRP2 expression by shRNA in colorectal cancer cells induces smaller tumors, decreased number of metastases and enhanced apoptosis in comparison with control shRNA in a murine xenograft model [45]. In addition, intraperitoneally treatment of tumor bearing mice with liposomes containing NRP2 siRNA reduces tumor growth and metastasis [45].

6.2. Small Molecules

As seen previously, alternative splicing generates naturally occurring soluble forms sNRP1 and sNRP2. These soluble sNRP are first described as inhibitory molecules, functioning as natural ligand trap, inhibiting their interaction with membrane receptors. Soluble neuropilins lack the transmembrane segment and intracellular domain. Gagnon et al. reported that overexpression of sNRP1 in Dunning rat prostate carcinoma cell lines AT2.1 and AT3.1 generates tumors with large and hemorrhagic center, with decreased proliferation and increased apoptosis in rats [28]. Moreover, sNRP1 inhibits the binding of VEGF165 to full-length NRP1 [28].

Schuch et al. confirmed these findings in a murine sarcoma model using NMuMG/VEGF and NMuMG/sNRP-1 cells that have been engineered to produce high levels of recombinant VEGF and sNRP1 [148]. VEGF treatment resulted in tumor growth and vascularization, whereas treatment with soluble NRP-1 (sNRP-1) inhibited tumor angiogenesis and growth. Moreover, in a systemic leukemia model, survival of mice injected with adenovirus (Ad) encoding for Fc-sNRP-1 (sNRP-1 dimer) was significantly prolonged as compared with control mice [148].

Since naturally occurring soluble forms of neuropilins are described to inhibit tumor progression, researchers tend nowadays to develop soluble peptides preventing VEGF-binding on neuropilins. For this purpose, Geretti et al. described very recently a mutant of the B-domain of NRP2 (MutB-NRP2) with 8-fold increased affinity for VEGF compared to wild-type B domain of NRP2 [149]. This MutB-NRP2 significantly inhibits tumor growth in a xenograft model using melanoma cells, alone and in combination with bevacizumab [149].

Furthermore, screening of phage libraries expressing random peptides binding to various cancer cells has allowed the identification of amino acid sequences especially binding NRPs. Indeed, Sugahara and collaborators reported two tissue-penetrating peptides binding human integrins and NRP1 capable of penetrating into tumor tissue and cells [150,151]. Conjugation of these peptides to anti-tumor drugs or imaging agents might enhance tumor imaging and the activity of anti-tumor therapies [150-152]. Since then, another peptide targeting NRP1 has been described in various model of cancers cell in vitro [153-155].

6.3. Monoclonal Antibodies

Genentech has very recently developed monoclonal antibodies targeting NRP1. In particularly, high-affinity monoclonal antibodies targeting either CUB domains (anti-NRP1A) or coagulation factors V/VIII domains (anti-NRP1B) of NRP1 have been first generated. [156] These anti-NRP1 antibodies induce reduction of VEGF-induced migration of HUVEC cells and inhibit tumor formation in animal models [156]. Later, anti-NRP1 monoclonal antibodies were shown to block VEGF-binding to NRP1 and to have an additive effect with anti-VEGF therapies to reduce tumor growth [157].

One of them, a full human antibody targeting NRP1, MNRP1685A is actually in phase-1 of development alone or in combination with bevacizumab with or without paclitaxel for treatment of advanced solid tumors [158].

Monoclonal antibodies targeting the b1/b2 domains of NRP2 have been recently developed. By blocking binding of VEGF and VEGFC to NRP2, these anti-NRP2B monoclonal antibodies decrease the number of tumor-associated lymphatic vessels and metastasis in sentinel lymph node and in distant organs in mice xenograft experiments [131].

6.4. Semaphorins

NRPs role in tumorigenesis is more complex than initially thought and appears to depend on the nature of the ligand. In the context of cancer, it appears that semaphorins and VEGF are competing for NRPs binding, although they bind different NRPs sub-units. While semaphorins are responsible for inhibition of tumor growth, proliferation and even induction of apoptosis in cancer cells, VEGF tends to oppositely enhance angiogenesis and tumor growth. As described above, some semaphorins such as Sema3B and Sema3F are considered as TSG and are very often downregulated in cancer cells [102,104,120]. Overexpression of Sema3 genes may represent a promising new type of therapy for preventing tumor angiogenesis, growth, and metastasis. Moreover, other semaphorins such as Sema3E or Sema4D function as pro-angiogenic and pro-oncogenic molecules [89,126,159,160]. Neutralization of these molecules or their relative receptors thus may represent a new therapeutic strategy for cancer treatment. In particular, one monoclonal antibody VX15/2503 binding to the sema4D is currently in phase-1 of development for the treatment of advanced solid tumors [161]. Therapeutic use of semaphorin pathway seems to represent one of the major therapeutic strategies considered, capable of antagonizing VEGF-mediated angiogenesis and tumor progression [88].

7. Conclusions

NRPs are multifunctional non-tyrosine kinase receptors for class-3 semaphorins and VEGF family members implicated in both physiological development and pathological situations. NRPs are expressed in endothelial cells and in many types of cancer cells. Through their direct interactions with plexins or growth factor receptors, NRPs have rapidly emerged as key regulators of angiogenesis, lymphangiogenesis, EMT and tumor progression. In many cancers, expression of one or both has been correlated with tumor progression and/or poor prognosis. As a consequence, several strategies have been used in pre-clinical studies to inhibit NRPs function, such as knockdown strategies with siRNAs, small peptide inhibitors, and blocking antibodies. However, the molecular mechanisms by which NRPs modulate cancer progression are still poorly understood. Understanding the interactions between VEGF, VEGFRs, semaphorins and NRPs should provide additional data for the rational development of novel anti-tumor strategies.

| Tumors | NRP1 | NRP2 | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain tumors | |||||||

| Astrocytomas | x | ND | Ding H et al., 2000 [56] | ||||

| Neuroblastomas | x | x | Fakhari M et al. [44] | ||||

| Gliomas | x | x | Rieger J et al., 2003 [43] | ||||

| x | ND | Osada H et al., 2004 [54] | |||||

| Glioblastomas | x | ND | Broholm H et al., 2004 [57] | ||||

| Pituitary tumors | x | ND | Onofri C et al., 2006 [58] | ||||

| Digestive tumors | |||||||

| Endocrine pancreatic tumors | ND | x | Cohen T et al., 2002 [47] | ||||

| Pancreatic adenocarcinomas | x | ND | Parikh AA et al., 2003 [59] | ||||

| x | x | Fukahi K et al., 2004 [48] | |||||

| x | x | Li M et al., 2004 [49] | |||||

| x | ND | Feurino LW et al., 2007 [60] | |||||

| x | x | Dallas NA et al., 2008 [46] | |||||

| Gastric cancer | x | ND | Akagi M et al., 2003 [61] | ||||

| x | ND | Hansel DE et al., 2004 [62] | |||||

| Colon cancer | x | ND | Parikh AA et al., 2004 [63] | ||||

| x | ND | Ochiumi T et al., 2006 [64] | |||||

| ND | x | Gray MJ et al., 2008 [45] | |||||

| Leukemias | |||||||

| Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) | x | ND | Kreuter M et al., 2006 [65] | ||||

| x | ND | Kreuter M et al., 2007 [66] | |||||

| x | x | Vales A et al., 2007 [51] | |||||

| x | ND | Lu L et al., 2007 [67] | |||||

| Chronic lymphocytic leukemia B | x | ND | Nowakowski GS et al., 2008 [68] | ||||

| Other solid tumors | |||||||

| Breast cancers | x | ND | Stephenson JM et al., 2002 [69] | ||||

| x | ND | Ghosh M et al., 2008 [70] | |||||

| NSCLC | x | x | Kawakami T et al., 2002 [41] | ||||

| x | x | Lantuejoul S et al., 2003 [71] | |||||

| Lung cancers | x | x | Tomizawa et al., 2001 [42] | ||||

| Melanomas | x | x | Lacal PM et al., 2000 [40] | ||||

| x | ND | Straume O et al., 2003 [72] | |||||

| Prostate cancers | x | ND | Latil A et al., 2000 [73] | ||||

| x | ND | Vanveldhuizen PJ et al., 2003 [74] | |||||

| Laryngeal carcinomas and papillomas | x | ND | Zhang S et al., 2006 [75] | ||||

| Salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma | ND | x | Cai Y et al., 2010 [52] | ||||

| Infantile hemangiomas | ND | x | Calicchio ML et al., 2009 [53] | ||||

| Ovarian carcinomas | x | ND | Hall GH et al., 2005 [76] | ||||

| x | x | Osada R et al., 2006 [54] | |||||

| x | ND | Baba T et al., 2007 [77] | |||||

| Bladder cancers | ND | x | Sanchez Carbayo M et al., 2003 [55] | ||||

| Osteosarcomas | ND | x | Handa et al., 2000 [39] |

| Semaphorins | Cells | Activity | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sema3A | Neural progenitor cells | Induction of cell repulsion and cell death | Bagnard D, 2001[109] |

| Endothelial cells | Induction of apoptosis | Guttmann-Raviv N, 2007 [110] | |

| Leukemic T cells | Relocalization of Fas into the lipid raft | Moretti S, 2008 [111] | |

| Breast cancer cells | Inhibition of tumor growth, of intra-tumor vasculature | Kigel B, 2008 [112] | |

| Breast tumor cells | Inhibition of cell migration, increase of alpha2beta1 integrin level | Pan H, 2009 [127] | |

| Sema3B | murine pancreatic cells | Inhibition of tumor growth, of intra-tumor vasculature | Maione F, 2009 [113] |

| murine mammary carcinoma cells | Inhibition of tumor growth, of intra-tumor vasculature and metastasis | Casazza A, 2011 [114] | |

| Lung cancer cells | Inhibition of growth and induction of apoptosis | Tomizawa, 2001 [42] | |

| Ovarian adenocarcinoma cell line | Diminution of tumorigenicity in xenografts experiments, diminution of colony formation and cell proliferation | Tse C, 2002 [115] | |

| Lung and breast cancer cells | Induction of apoptosis | Castro-Rivera E, 2004, 2008 [116, 117] | |

| Breast cancer cells | NRP1-sema3B interactions increase IL8 production in tumor cells, promoting invasion and metastasis | Rolny C, 2008 [118] | |

| Sema3D | Breast cancer cells | Inhibition of tumor progression | Kigel B, 2008 [112] |

| Sema3E | Breast cancer cells | Increase of tumor growth, metastasis | Christensen C, 2005 [126] |

| Sema3F | Lung cancer cells | Role in cell motility and cell adhesion | Brambilla E, 2000 [119] |

| Small cell lung cancer cells, ovarian adenocarcinoma | Diminution of tumorigenicity in xenografts experiments, induction of apoptosis | Xiang R, 2002 [120] | |

| Breast cancer cells | Inhibition of cell migration | Nasarre P, 2003 [128] | |

| Endothelial, renal cancer cells | Inhibition of cell proliferation, inhibition of angiogenesis in vivo | Kessler O, 2004 [122] | |

| Melanomas | Inhibition of metastasis, of intra-tumor vessels and induction of large areas of apoptosis in vivo | Bielenberg BR, 2004[123] | |

| Breast cancer cells | Induction of cell repulsion, inhibition of cell contacts and proliferation | Nasarre P, 2005 [125] | |

| Lung cancer cells | Enhances survival in xenografts experiment | Kusy S, 2005 [121] | |

| Melanomas | Inhibition of cell proliferation | Chabbert-de Ponnat I, 2006 [124] | |

| Breast and melanoma cancer cells | Inhibition of tumor progression in vivo | Kigel B, 2008 [112] |

| Complexes | Cells | Activity | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| NRP/VEGFR1 | Biacore analysis | NRP1 associates with VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 | Fuh et al., 2000 [19] |

| Endothelial Porcine Aortic Endothelial (PAE) cells | NRP2 co-immunoprecipitates with VEGFR1 | Gluzman-Poltorak et al., 2001 [129] | |

| Colorectal cancer cells | NRP2 enhances VEGFR1 phosphorylation, migration, invasion in tumor cells through PI3K and ERK activation. Targeting NRP2 with shRNA reduces tumor growth, metastasis formation in xenograft experiments. | Gray et al., 2008 [45] | |

| NRP/VEGFR2 | Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma cancer cells | NRP2 enhances VEGFR1 phosphorylation, migration, invasion in tumor cells through PI3K and ERK activation. Reduced NRP-2 expression decreases migration, invasion, and anchorage-independent growth. Targeting NRP2 with shRNA reduces tumor growth, tumor vasculature and metastasis formation in xenograft experiments. | Dallas et al., 2008 [46] |

| Endothelial Porcine Aortic Endothelial (PAE) cells | NRP1 enhances the binding of VEGF to VEGFR2 | Soker et al., 1998 [21] | |

| Biacore analysis | NRP1 associates with VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 | Fuh et al., 2000 [19] | |

| 293T, PAE, human microvascular endothelial cells | NRP2 interacts with VEGFR2 and VEGFR3 and enhances their activation. NRP2 overexpression enhances VEGF-A and VEGF-C induced survival and migration of human endothelial cells. | Favier et al., 2006 [130] | |

| Lymphatic endothelial cells | NRP2 interacts with VEGFR2 and VEGFR3, enhances their phosphorylation and activation. | Caunt et al., 2008 [131] | |

| NRP/VEGFR3 | Lymphatic endothelial cells and transfected 293T | NRP2 interacts with VEGFR3 in co-immunoprecipitation studies. | Karpänen et al., 2006 [20] |

| 293T, PAE, human microvascular endothelial cells | NRP2 interacts with VEGFR2 and VEGFR3 and enhances their activation. NRP2 overexpression enhances VEGF-A and VEGF-C induced survival and migration of human endothelial cells. | Favier et al., 2006 [130] | |

| Lymphatic endothelial cells | NRP2 interacts with VEGFR2 and VEGFR3, enhances their phosphorylation and activation. | Caunt et al., 2008 [131] | |

| NRP/c-met | HUVEC | HGF binds NRP1 and NRP2. NRP1 and NRP2 enhance c-met phosphorylation and migration through ERK activation. | Sulpice et al., 2008 [24] |

| Glioma | NRP1 promotes glioma progression through activation of HGF/SF autocrine pathway and ERK pathway activation. | Hu B et al., 2007 [137] | |

| Pancreatic cancer cells | NRP1 interacts with c-met, promoting invasion through ERK and p38MAPK activation. | Matsushita et al., 2007 [138] | |

| NRP/TGFR | Stromal fibroblasts | NRP1 enhances Smad activation and induces a myofibroblast phenotype. | Cao et al., 2010 [142] |

| Breast cancer cells | NRP1 and NRP2 associate with TGFRI and TGFRII and enhance Smad2/3 phosphorylation. | Glinka et al., 2010 [140] | |

| Colorectal cancer cells | NRP2 interacts with TGFRI and enhances Smad2/3 activation. NRP2 induces a TGFβi-dependant Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition in colorectal cancer cells. | Grandclement et al., 2010 [143] |

Acknowledgments

C.G. has received a fellowship from the “ANRT: Agence Nationale pour la Recherche Technologique”; This work has been supported by the “Ligue contre le cancer, comite du Doubs”, and by the University Hospital of Besançon.

References

- Takagi, S.; Tsuji, T.; Amagai, T.; Takamatsu, T.; Fujisawa, H. Specific cell surface labels in the visual centers of Xenopus laevis tadpole identified using monoclonal antibodies. Dev. Biol. 1987, 122, 90–100. [Google Scholar]

- Takagi, S.; Kasuya, Y.; Shimizu, M.; Matsuura, T.; Tsuboi, M.; Kawakami, A.H.F. Expression of a cell adhesion molecule, neuropilin, in the developing chick nervous system. Dev. Biol. 1995, 170, 207–222. [Google Scholar]

- Yamagata, M.; Herman, J.P.; Sanes, J.R. Lamina-specific expression of adhesion molecules in developing chick optic tectum. J. Neurosci. 1995, 15, 4556–4571. [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami, A.; Kitsukawa, T.; Takagi, S.H.F. Developmentally regulated expression of a cell surface protein, neuropilin, in the mouse nervous system. J. Neurobiol. 1996, 29, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kolodkin, A.; Levengood, D.; Rowe, E.; Tai, Yu-Tzu.; Giger, R.; Ginty, D. Neuropilin is a Semaphorin III receptor. Cell 1997, 90, 753–762. [Google Scholar]

- He, Z.; Tessier-Lavigne, M. Neuropilin is a receptor for the axonal chemorepellent Semaphorin III. Cell 1997, 90, 739–751. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Chedotal, A.; He, Z.; Goodman, C.S.; Tessier-Lavigne, M. Neuropilin-2, a novel member of the neuropilin family, is a high affinity receptor for the semaphorins Sema E and Sema IV but not Sema III. Neuron 1997, 19, 547–559. [Google Scholar]

- Giger, R.J.; Urquhart, E.R.; Gillespie, S.K.; Levengood, D.V.; Ginty, D.D.; Kolodkin, A.L. Neuropilin-2 is a receptor for semaphorin IV: Insight into the structural basis of receptor function and specificity. Neuron 1998, 21, 1079–1092. [Google Scholar]

- Giger, R.J.; Cloutier, J.F.; Sahay, A.; Prinjha, R.K.; Levengood, D.V.; Moore, S.E.; Pickering, S.; Simmons, D.; Rastan, S.; Walsh, F.S.; et al. Neuropilin-2 is required in vivo for selective axon guidance responses to secreted semaphorins. Neuron 2000, 25, 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kitsukawa, T.; Shimizu, M.; Sanbo, M.; Hirata, T.; Taniguchi, M.; Bekku, Y.; Yagi, T.; Fujisawa, H. Neuropilin-semaphorin III/D-mediated chemorepulsive signals play a crucial role in peripheral nerve projection in mice. Neuron 1997, 19, 995–1005. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Bagri, A.; Zupicich, J.A. Neuropilin-2 regulates the development of selective cranial and sensory nerves and hippocampal mossy fiber projections. Neuron 2000, 25, 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kitsukawa, T.; Shimono, A.; Kawakami, A.; Kondoh, H.; Fujisawa, H. Overexpression of a membrane protein, neuropilin, in chimeric mice causes anomalies in the cardiovascular system, nervous system and limbs. Development 1995, 121, 4309–4318. [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki, T.; Kitsukawa, T.; Bekku, Y.; Matsuda, Y.; Sanbo, M.; Yagi, T.; Fujisawa, H. A requirement for neuropilin-1 in embryonic vessel formation. Development 1999, 126, 4895–4902. [Google Scholar]

- Takashima, S.; Kitakaze, M.; Asakura, M.; Asanuma, H.; Sanada, S.; Tashiro, F.; Niwa, H.; Miyazaki Ji, J.; Hirota, S.; Kitamura, Y.; et al. Targeting of both mouse neuropilin-1 and neuropilin-2 genes severely impairs developmental yolk sac and embryonic angiogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 3657–3662. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L.; Moyon, D.; Pardanaud, L.; Breant, C.; Karkkainen, M.J.; Alitalo, K.; Eichmann, A. Abnormal lymphatic vessel development in neuropilin 2 mutant mice. Development 2002, 129, 4797–4806. [Google Scholar]

- Mäkinen, T.; Olofsson, B.; Karpanen, T.; Hellman, U.; Soker, S.; Klagsbrun, M.; Eriksson, U.; Alitalo, K. Differential binding of vascular endothelial growth factor B splice and proteolytic isoforms to neuropilin-1. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 21217–21222. [Google Scholar]

- Migdal, M.; Huppertz, B.; Tessler, S.; Comforti, A.; Shibuya, M.; Reich, R.; Baumann, H.; Neufeld, G. Neuropilin-1 is a placenta growth factor-2 receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 22272–22278. [Google Scholar]

- Gluzman-Poltorak, Z.; Cohen, T.; Herzog, Y.; Neufeld, G. Neuropilin-2 and neuropilin-1 are receptors for the 165-amino acid form of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and of placenta growth factor-2, but only neuropilin-2 functions as a receptor for the 145-amino acid form of VEGF. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 18040–18045. [Google Scholar]

- Fuh, G.; Garcia, K.C.; de Vos, A.M. The interaction of neuropilin-1 with vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptor flt-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 26690–26695. [Google Scholar]

- Kärpänen, T.; Heckman, C.A.; Keskitalo, S.; Jeltsch, M.; Ollila, H.; Neufeld, G.; Tamagnone, L.; Alitalo, K. Functional interaction of VEGF-C and VEGF-D with neuropilin receptors. FASEB J. 2006, 20, 1462–1472. [Google Scholar]

- Soker, S.; Takashima, S.; Miao, H.Q.; Neufeld, G.; Klagsbrun, M. Neuropilin-1 is expressed by endothelial and tumor cells as an isoform-specific receptor for vascular endothelial growth factor. Cell 1998, 92, 735–745. [Google Scholar]

- Karkkainen, M.J.; Saaristo, A.; Jussila, L.; Karila, K.A.; Lawrence, E.C.; Pajusola, K.; Bueler, H.; Eichmann, A.; Kauppinen, R.; Kettunen, M.I.; et al. A model for gene therapy of human hereditary lymphedema. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 12677–12682. [Google Scholar]

- West, D.C.; Rees, C.G.; Duchesne, L.; Patey, S.J.; Terry, C.J.; Turnbull, J.E.; Delehedde, M.; Heegaard, C.W.; Allain, F.; Vanpouille, C.; et al. Interactions of multiple heparin binding growth factors with neuropilin-1 and potentiation of the activity of fibroblast growth factor-2. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 13457–13464. [Google Scholar]

- Sulpice, E.; Plouët, J.; Bergé, M.; Allanic, D.; Tobelem, G.; Merkulova-Rainon, T. Neuropilin-1 and neuropilin-2 act as coreceptors, potentiating proangiogenic activity. Blood 2008, 111, 2036–2045. [Google Scholar]

- Rossignol, M.; Gagnon, M.L.; Klagsbrun, M. Genomic organization of human neuropilin-1 and neuropilin-2 genes: Identification and distribution of splice variants and soluble isoforms. Genomics 2000, 70, 211–222. [Google Scholar]

- Takagi, S.; Hirata, T.; Agata, K.; Mochii, M.; Eguchi, G.; Fujisawa, H. The A5 antigen, a candidate for the neuronal recognition molecule, has homologies to complement components and coagulation factors. Neuron 1991, 7, 295–307. [Google Scholar]

- Cackowski, F.C.; Xu, L.; Hu, B.; Cheng, S.Y. Identification of two novel alternatively spliced Neuropilin-1 isoforms. Genomics 2004, 84, 82–94. [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon, M.L.; Bielenberg, D.R.; Gechtman, Z.; Miao, H.Q.; Takashima, S.; Soker, S.; Klagsbrun, M. Identification of a natural soluble neuropilin-1 that binds vascular endothelial growth factor: In vivo expression and antitumor activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 2573–2578. [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa, H.; Takagi, S.; Hirata, T. Growth-associated expression of a membrane protein, neuropilin, in Xenopus optic nerve fibers. Dev. Neurosci. 1995, 17, 343–349. [Google Scholar]

- Tordjman, R.; Lepelletier, Y.; Lemarchandel, V.; Cambot, M.; Gaulard, P.; Hermine, O.; Roméo, P.H. A neuronal receptor, neuropilin-1, is essential for the initiation of the primary immune response. Nat. Immunol. 2002, 3, 477–482. [Google Scholar]

- Bruder, D.; Probst-Kepper, M.; Westendorf, A.M.; Geffers, R.; Beissert, S.; Loser, K.; von Boehmer, H.; Buer, J.; Hansen, W. Neuropilin-1: A surface marker of regulatory T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2004, 34, 623–630. [Google Scholar]

- Sarris, M.; Andersen, K.G.; Randow, F.; Mayr, L.; Betz, A.G. Neuropilin-1 expression on regulatory T cells enhances their interactions with dendritic cells during antigen recognition. Immunity 2008, 28, 402–413. [Google Scholar]

- Milpied, P.; Renand, A.; Bruneau, J.; Mendes-da-Cruz, D.A.; Jacquelin, S.; Asnafi, V.; Rubio, M.T.; MacIntyre, E.; Lepelletier, Y.; Hermine, O. Neuropilin-1 is not a marker of human Foxp3+ Treg. Eur. J. Immunol. 2009, 39, 1466–1471. [Google Scholar]

- Curreli, S.; Arany, Z.; Gerardy-Schahn, R.; Mann, D.; Stamatos, N.M. Polysialylated neuropilin-2 is expressed on the surface of human dendritic cells and modulates dendritic cell-T lymphocyte interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 30346–30356. [Google Scholar]

- Rey-Gallardo, A.; Delgado-Martín, C.; Gerardy-Schahn, R.; Rodríguez-Fernandez, J.L.; Vega, M.A. Polysialic acid is required for Neuropilin-2a/b-mediated control of CCL21-driven chemotaxis of mature dendritic cells, and for their migration in vivo. Glycobiology 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-Gallardo, A.; Escribano, C.; Delgado-Martín, C.; Rodriguez-Fernández, J.L.; Gerardy-Schahn, R.; Rutishauser, U.; Corbi, A.L.; Vega, M.A. Polysialylated neuropilin-2 enhances human dendritic cell migration through the basic C-terminal region of CCL21. Glycobiology 2010, 20, 1139–1146. [Google Scholar]

- Bielenberg, D.R.; Pettaway, C.A.; Takashima, S.; Klagsburn, M. Neuropilins in neoplasms: Expression, regulation, and function. Exp. Cell Res. 2006, 312, 584–593. [Google Scholar]

- Pellet-Many, C.; Frankel, P.; Jia, H.; Zachary, I. Neuropilins: Structure, function and role in disease. Biochem. J. 2008, 411, 211–226. [Google Scholar]

- Handa, A.; Tokunaga, T.; Tsuchida, T.; Lee, Y.H.; Kijima, H.; Yamazaki, H.; Ueyama, Y.; Fukuda, H.; Nakamura, M. Neuropilin-2 expression affects the increased vascularization and is a prognostic factor in osteosarcoma. Int. J. Oncol. 2000, 17, 291–295. [Google Scholar]

- Lacal, P.M.; Failla, C.M.; Pagani, E.; Odorisio, T.; Schietroma, C.; Falcinelli, S.; Zambruno, G.; D'Atri, S. Human melanoma cells secrete and respond to placenta growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2000, 115, 1000–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami, T.; Tokunaga, T.; Hatanaka, H.; Kijima, H.; Yamazaki, H.; Abe, Y.; Osamura, Y.; Inoue, H.; Ueyama, Y.; Nakamura, M. Neuropilin 1 and neuropilin 2 co-expression is significantly correlated with increased vascularity and poor prognosis in nonsmall cell lung carcinoma. Cancer 2002, 95, 2196–2201. [Google Scholar]

- Tomizawa, Y.; Sekido, Y.; Kondo, M.; Gao, B.; Yokota, J.; Roche, J.; Drabkin, H.; Lerman, M.I.; Gazdar, A.F.; Minna, J.D. Inhibition of lung cancer cell growth and induction of apoptosis after reexpression of 3p21.3 candidate tumor suppressor gene SEMA3B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 13954–13959. [Google Scholar]

- Rieger, J.; Wick, W.; Weller, M. Human malignant glioma cells express semaphorins and their receptors, neuropilins and plexins. Glia 2003, 42, 379–389. [Google Scholar]

- Fakhari, M.; Pullirsch, D.; Abraham, D.; Paya, K.; Hofbauer, R.; Holzfeind, P.; Hofmann, M.; Aharinejad, S. Selective upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors neuropilin-1 and -2 in human neuroblastoma. Cancer 2002, 94, 258–263. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, M.J.; Van Buren, G.; Dallas, N.A.; Xia, L.; Wang, X.; Yang, A.D.; Somcio, R.J.; Lin, Y.G.; Lim, S.; Fan, F.; et al. Therapeutic targeting of neuropilin-2 on colorectal carcinoma cells implanted in the murine liver. J. Nat. Cancer Inst. 2008, 100, 109–120. [Google Scholar]

- Dallas, N.A.; Gray, M.J.; Xia, L.; Fan, F.; van Buren, G., 2nd.; Gaur, P.; Samuel, S.; Lim, S.J.; Arumugam, T.; Ramachandran, V.; Wang, H.; Ellis, L.M. Neuropilin-2-mediated tumor growth and angiogenesis in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 8052–8060. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, T.; Herzog, Y.; Brodzky, A.; Greenson, J.K.; Eldar, S.; Gluzman-Poltorak, Z.; Neufeld, G.; Resnick, M.B. Neuropilin-2 is a novel marker expressed in pancreatic islet cells and endocrine pancreatic tumours. J. Pathol. 2002, 198, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Fukahi, K.; Fukasawa, M.; Neufeld, G.; Itakura, J.; Korc, M. Aberrant expression of neuropilin-1 and -2 in human pancreatic cancer cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 581–590. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Yang, H.; Chai, H.; Fisher, W.E.; Wang, X.; Brunicardi, F.C.; Yao, Q.; Chen, C. Pancreatic carcinoma cells express neuropilins and vascular endothelial growth factor, but not vascular endothelial growth factor receptors. Cancer 2004, 101, 2341–2350. [Google Scholar]

- Yasuoka, H.; Kodama, R.; Tsujimoto, M.; Yoshidome, K.; Akamatsu, H.; Nakahara, M.; Inagaki, M.; Sanke, T.; Nakamura, Y. Neuropilin-2 expression in breast cancer: Correlation with lymph node metastasis, poor prognosis, and regulation of CXCR4 expression. BMC Cancer 2009, 7, 220. [Google Scholar]

- Vales, A.; Kondo, R.; Aichberger, K.J.; Mayerhofer, M.; Kainz, B.; Sperr, W.R.; Sillaber, C.; Jager, U.; Valent, P. Myeloid leukemias express a broad spectrum of VEGF receptors including neuropilin-1 (NRP-1) and NRP-2. Leuk. Lymphoma 2007, 48, 1997–2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhao, Y.F.; Jia, J.; Sun, Z.J.; Chen, X.M. Expression of Neuropilin-2 in salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma: Its implication in tumor progression and angiogenesis. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2010, 206, 793–799. [Google Scholar]

- Calicchio, M.L.; Collins, T.; Kozakewich, H.P. Identification of signaling systems in proliferating and involuting phase infantile hemangiomas by genome-wide transcriptional profiling. Am. J. Pathol. 2009, 174, 1638–1649. [Google Scholar]

- Osada, R.; Horiuchi, A.; Kikuchi, N.; Ohira, S.; Ota, M.; Katsuyama, Y.; Konishi, I. Expression of semaphorins, vascular endothelial growth factor, and their common receptor neuropilins and alleic loss of semaphorin locus in epithelial ovarian neoplasms: Increased ratio of vascular endothelial growth factor to semaphorin is a poor prognostic factor in ovarian carcinomas. Hum. Pathol. 2006, 37, 1414–1425. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Carbayo, M.; Socci, N.D.; Lozano, J.J.; Li, W.; Charytonowicz, E.; Belbin, T.J.; Prystowsky, M.B.; Ortiz, A.R.; Childs, G.; Cordon-Cardo, C. Gene discovery in bladder cancer progression using cDNA microarrays. Am. J. Pathol. 2003, 163, 505–516. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, H.; Wu, X.; Roncari, L.; Lau, N.; Shannon, P.; Nagy, A.; Guha, A. Expression and regulation of neuropilin-1 in human astrocytomas. Int. J. Cancer 2000, 88, 584–592. [Google Scholar]

- Broholm, H.; Laursen, H. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor neuropilin-1's distribution in astrocytic tumors. APMIS 2004, 112, 257–263. [Google Scholar]

- Onofri, C.; Theodoropoulou, M.; Losa, M.; Uhl, E.; Lange, M.; Arzt, E.; Stalla, G.K.; Renner, U. Localization of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptors in normal and adenomatous pituitaries: detection of a non-endothelial function of VEGF in pituitary tumours. J. Endocrinol. 2006, 191, 249–261. [Google Scholar]

- Parikh, A.A.; Liu, W.B.; Fan, F. Expression and regulation of the novel vascular endothelial growth factor receptor neuropilin-1 by epidermal growth factor in human pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer 2003, 98, 720–729. [Google Scholar]

- Feurino, L.W.; Zhang, Y.; Bharadwaj, U.; Zhang, R.; Li, F.; Fisher, W.E.; Brunicardi, F.C.; Chen, C.; Yao, Q.; Min, L. IL-6 stimulates Th2 type cytokine secretion and upregulates VEGF and NRP-1 expression in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2007, 6, 1096–1100. [Google Scholar]

- Akagi, M.; Kawaguchi, M.; Liu, W.; McCarty, M.F.; Takeda, A.; Fan, F.; Stoeltzing, O.; Parikh, A.A.; Jung, Y.D.; Bucana, C.D.; et al. Induction of neuropilin-1 and vascular endothelial growth factor by epidermal growth factor in human gastric cancer cells. Br. J. Cancer 2003, 88, 796–802. [Google Scholar]

- Hansel, D.E.; Wilentz, R.E.; Yeo, C.J.; Schulick, R.D.; Montgomery, E.; Maitra, A. Expression of neuropilin-1 in high-grade dysplasia, invasive cancer, and metastases of the human gastrointestinal tract. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2004, 28, 347–356. [Google Scholar]

- Parikh, A.A.; Fan, F.; Liu, W.B. Neuropilin-1 in human colon cancer: Expression, regulation, and role in induction of angiogenesis. Am. J. Path. 2004, 164, 2139–2151. [Google Scholar]

- Ochiumi, T.; Kitadai, Y.; Tanaka, S.; Akagi, M.; Yoshihara, M.; Chayama, K. Neuropilin-1 is involved in regulation of apoptosis and migration of human colon cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 2006, 29, 105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter, M.; Woelke, K.; Bieker, R.; Schliemann, C.; Steins, M.; Buechner, T.; Berdel, W.E.; Mesters, R.M. Correlation of neuropilin-1 overexpression to survival in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2006, 20, 1950–1954. [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter, M.; Steins, M.; Woelke, K.; Buechner, T.; Berdel, W.E.; Mesters, R.M. Downregulation of neuropilin-1 in patients with acute myeloid leukemia treated with thalidomide. Eur. J. Haematol. 2007, 79, 392–397. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, L.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, Z.; Lu, S.; Yang, R.; Han, Z.C. Neuropilin-1 in acute myeloid leukemia: expression and role in proliferation and migration of leukemia cells. Leuk. Lymphoma 2008, 49, 331–338. [Google Scholar]

- Nowakowski, G.S.; Mukhopadhyay, D.; Wu, X.; Kay, N.E. Neuropilin-1 is expressed by chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. Leuk. Res. 2008, 32, 1634–1636. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, J.M.; Banerjee, S.; Saxena, N.K.; Cherian, R.; Banerjee, S.K. Neuropilin-1 is differentially expressed in myoepithelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells in preneoplastic and neoplastic human breast: A possible marker for the progression of breast cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2002, 101, 409–414. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, S.; Sullivan, C.A.; Zerkowski, M.P.; Molinaro, A.M.; Rimm, D.L.; Camp, R.L.; Chung, G. G. High levels of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors (VEGFR-1, VEGFR-2, neuropilin-1) are associated with worse outcome in breast cancer. Hum. Pathol. 2008, 39, 1835–1843. [Google Scholar]

- Lantuéjoul, S.; Constantin, B.; Drabkin, H.; Brambilla, C.; Roche, J.; Brambilla, E. Expression of VEGF, semaphorin SEMA3F, and their common receptors neuropilins NP1 and NP2 in preinvasive bronchial lesions, lung tumours, and cell lines. J. Pathol. 2003, 200, 336–347. [Google Scholar]

- Straume, O.; Akslen, L.A. Increased expression of VEGF-receptors (FLT-1, KDR, NRP-1) and thrombospondin-1 is associated with glomeruloid microvascular proliferation, an aggressive angiogenic phenotype, in malignant melanoma. Angiogenesis 2003, 6, 295–301. [Google Scholar]

- Latil, A.; Bièche, I.; Pesche, S.; Valéri, A.; Fournier, G.; Cussenot, O.; Lidereau, R. VEGF overexpression in clinically localized prostate tumors and neuropilin-1 overexpression in metastatic forms. Int. J. Cancer 2000, 89, 167–171. [Google Scholar]

- Vanveldhuizen, P.J.; Zulfiqar, M.; Banerjee, S.; Cherian, R.; Saxena, N.K.; Rabe, A.; Thrasher, J.B.; Banerjee, S.K. Differential expression of neuropilin-1 in malignant and benign prostatic stromal tissue. Oncol. Rep. 2003, 10, 1067–1071. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Kong, W. Expression of neuropilin-1 in human laryngeal carcinoma and cell lines. Lin Chuang Er Bi Yan Hou Ke Za Zhi 2006, 20, 634–635. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, G.H.; Turnbull, L.W.; Bedford, K.; Richmond, I.; Helboe, L.; Atkin, S.L. Neuropilin-1 and VEGF correlate with somatostatin expression and microvessel density in ovarian tumours. Int. J. Oncol. 2005, 27, 1283–1288. [Google Scholar]

- Baba, T.; Kariya, M.; Higuchi, T.; Mandai, M.; Matsumura, N.; Kondoh, E.; Miyanishi, M.; Fukuhara, K.; Takakura, K.; Fujii, S. Neuropilin-1 promotes unlimited growth of ovarian cancer by evading contact inhibition. Gynecol. Oncol. 2007, 105, 703–711. [Google Scholar]

- Ottino, P.; Finley, J.; Rojo, E.; Ottlecz, A.; Lambrou, G.N.; Bazan, H.E.; Bazan, N.G. Hypoxia activates matrix metalloproteinase expression and the VEGF system in monkey choroid-retinal endothelial cells: Involvement of cytosolic phospholipase A2 activity. Mol. Vis. 2004, 10, 341–350. [Google Scholar]

- Brusselmans, K.; Bono, F.; Collen, D.; Herbert, J.M.; Carmeliet, P.; Dewerchin, M. A novel role for vascular endothelial growth factor as an autocrine survival factor for embryonic stem cells during hypoxia. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 3493–3499. [Google Scholar]

- Jögi, A.; Vallon-Christersson, J.; Holmquist, L.; Axelson, H.; Borg, A.; Påhlman, S. Human neuroblastoma cells exposed to hypoxia: Induction of genes associated with growth, survival, and aggressive behavior. Exp. Cell Res. 2004, 295, 469–487. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.G.; Tsang, W.; Zhang, L.; Powers, C.; Chopp, M. Up-regulation of neuropilin-1 in neovasculature after focal cerebral ischemia in the adult rat. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2001, 21, 541–549. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, H.; Acker, T.; Püschel, A.W.; Fujisawa, H.; Carmeliet, P.; Plate, K.H. Cell type-specific expression of neuropilins in an MCA-occlusion model in mice suggests a potential role in post-ischemic brain remodeling. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2002, 61, 339–350. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Feurino, L.W.; Wang, H.; Fisher, W.E.; Brunicardi, F.C.; Chen, C.; Yao, Q. Interleukin-8 increases vascular endothelial growth factor and neuropilin expression and stimulates ERK activation in human pancreatic cancer. Cancer Sci. 2008, 99, 733–737. [Google Scholar]

- Giraudo, E.; Primo, L.; Audero, E.; Gerber, H.P.; Koolwijk, P.; Soker, S.; Klagsbrun, M.; Ferrara, N.; Bussolino, F. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha regulates expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 and of its co-receptor neuropilin-1 in human vascular endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 22128–22135. [Google Scholar]

- Schramek, H.; Sarközi, R.; Lauterberg, C.; Kronbichler, A.; Pirklbauer, M.; Albrecht, R.; Noppert, S.J.; Perco, P.; Rudnicki, M.; Strutz, F.M.; Mayer, G. Neuropilin-1 and neuropilin-2 are differentially expressed in human proteinuric nephropathies and cytokine-stimulated proximal tubular cells. Lab. Invest. 2009, 89, 1304–1316. [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld, G.; Kessler, O. The semaphorins: Versatile regulators of tumour progression and tumour angiogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2008, 8, 632–645. [Google Scholar]

- Gherardi, E.; Love, C.A.; Esnouf, R.M.; Jones, E.Y. The sema domain. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2004, 14, 669–678. [Google Scholar]

- Capparuccia, L.; Tamagnone, L. Semaphorin signaling in cancer cells and in cells of the tumor microenvironment—two sides of a coin. J. Cell Sci. 2009, 122, 1723–1736. [Google Scholar]

- Basile, J.R.; Holmbeck, K.; Bugge, T.H.; Gutkind, J.S. MT1-MMP controls tumor-induced angiogenesis through the release of semaphorin 4D. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 6899–6905. [Google Scholar]

- Winberg, M.L.; Noordermeer, J.N.; Tamagnone, L.; Comoglio, P.M.; Spriggs, M.K.; Tessier-Lavigne, M.; Goodman, C.S. Plexin A is a neuronal semaphorin receptor that controls axon guidance. Cell 1998, 95, 903–916. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, T.; Fournier, A.; Nakamura, F.; Wang, L.H.; Murakami, Y.; Kalb, R.G.; Fujisawa, H.; Strittmatter, S.M. Plexin-neuropilin-1 complexes form functional semaphorin-3A receptors. Cell 1999, 99, 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Rohm, B.; Ottemeyer, A.; Lohrum, M.; Püschel, A.W. Plexin/neuropilin complexes mediate repulsion by the axonal guidance signal semaphorin 3A. Mech. Dev. 2000, 93, 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Fazzari, P.; Penachioni, J.; Gianola, S.; Rossi, F.; Eickholt, B.J.; Maina, F.; Alexopoulou, L.; Sottile, A.; Comoglio, P.M.; Flavell, R.A.; Tamagnone, L. Plexin-B1 plays a redundant role during mouse development and in tumour angiogenesis. BMC Dev. Biol. 2007, 7, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Rieger, J.; Wick, W.; Weller, M. Human malignant glioma cells express semaphorins and their receptors, neuropilins and plexins. Glia 2003, 42, 379–389. [Google Scholar]

- Rohm, B.; Rahim, B.; Kleiber, B.; Hovatta, I.; Püschel, A.W. The semaphorin 3A receptor may directly regulate the activity of small GTPases. FEBS Lett. 2000, 486, 68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Vikis, H.G.; Li, W.; He, Z.; Guan, K.L. The semaphorin receptor plexin-B1 specifically interacts with active Rac in a ligand-dependent manner. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 12457–12462. [Google Scholar]

- Driessens, M.H.; Hu, H.; Nobes, C.D.; Self, A.; Jordens, I.; Goodman, C.S.; Hall, A. Plexin-B semaphorin receptors interact directly with active Rac and regulate the actin cytoskeleton by activating Rho. Curr. Biol. 2001, 11, 339–344. [Google Scholar]

- Aurandt, J.; Vikis, H.G.; Gutkind, J.S.; Ahn, N.; Guan, K.L. The semaphorin receptor plexin-B1 signals through a direct interaction with the Rho-specific nucleotide exchange factor, LARG. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 12085–12090. [Google Scholar]

- Perrot, V.; Vázquez-Prado, J.; Gutkind, J.S. ; Plexin B regulates Rho through the guanine nucleotide exchange factors leukemia-associated Rho GEF (LARG) and PDZ-RhoGEF. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 43115–43120. [Google Scholar]

- Swiercz, J.M.; Kuner, R.; Behrens, J.; Offermanns, S. Plexin-B1 directly interacts with PDZ-RhoGEF/LARG to regulate RhoA and growth cone morphology. Neuron 2002, 35, 51–63. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, H.B.; Reed, R.R. Cloning and characterization of neuropilin-1 interacting protein: A PSD-95/Dlg/ZO-1 domain-containing protein that interacts with the cytoplasmic domain of neuropilin-1. J. Neurosci. 1999, 19, 6519–6527. [Google Scholar]

- Roche, J.; Boldog, F.; Robinson, M.; Robinson, L.; Varella-Garcia, M.; Swanton, B.; Waggoner, B.; Fishel, R.; Franklin, W.; Gemmill, R.; Drabkin, H. Distinct 3p21.3 deletions in lung cancer, analysis of deleted genes and identification of a new human semaphorin. Oncogene 1996, 12, 1289–1297. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, R.H.; Hensel, C.H.; Garcia, D.K.; Carlson, H.C.; Kok, K.; Daly, M.C.; Kerbacher, K.; van den Berg, A.; Veldhuis, P.; Buys, C.H.; Naylor, S.L. Isolation of the human semaphorin III/F gene (SEMA3F) at chromosome 3p21, a region deleted in lung cancer. Genomics 1996, 32, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, D.; Ho, S.M.; Syed, V. Hormonal regulation and distinct functions of semaphorin-3B and semaphorin-3F in ovarian cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2010, 9, 499–509. [Google Scholar]

- Burbee, D.G.; Forgacs, E.; Zöchbauer-Müller, S.; Shivakumar, L.; Fong, K.; Gao, B.; Randle, D.; Kondo, M.; Virmani, A.; Bader, S.; et al. Epigenetic inactivation of RASSF1A in lung and breast cancers and malignant phenotype suppression. J. Nat. Cancer Inst. 2001, 93, 691–699. [Google Scholar]

- Dammann, R.; Li, C.; Yoon, J.H.; Chin, P.L.; Bates, S.; Pfeifer, G.P. Epigenetic inactivation of a RAS association domain family protein from the lung tumour suppressor locus 3p21.3. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25, 315–319. [Google Scholar]

- Kuroki, T.; Trapasso, F.; Yendamuri, S.; Matsuyama, A.; Alder, H.; Williams, N.N.; Kaiser, L.R.; Croce, C.M. Allelic loss on chromosome 3p21.3 and promoter hypermethylation of semaphorin 3B in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 3352–3355. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, M.; Ito, G.; Kondo, M.; Uchiyama, M.; Fukui, T.; Mori, S.; Yoshioka, H.; Ueda, Y.; Shimokata, K.; Sekido, Y. Frequent inactivation of RASSF1A, BLU, and SEMA3B on 3p21.3 by promoter hypermethylation and allele loss in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Lett. 2005, 225, 131–139. [Google Scholar]

- Bagnard, D.; Vaillant, C.; Khuth, S.T.; Dufay, N.; Lohrum, M.; Puschel, A.W.; Belin, M.F.; Bolz, J.; Thomasset, N. Semaphorin 3A-vascular endothelial growth factor-165 balance mediates migration and apoptosis of neural progenitor cells by the recruitment of shared receptor. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 3332–3341. [Google Scholar]

- Guttmann-Raviv, N.; Shraga-Heled, N.; Varshavsky, A.; Guimaraes-Sternberg, C.; Kessler, O.; Neufeld, G. Semaphorin-3A and semaphorin-3F work together to repel endothelial cells and to inhibit their survival by induction of apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 26294–26305. [Google Scholar]

- Moretti, S.; Procopio, A.; Lazzarini, R.; Rippo, M.R.; Testa, R.; Marra, M.; Tamagnone, L.; Catalano, A. Semaphorin3A signaling controls Fas (CD95)-mediated apoptosis by promoting Fas translocation into lipid rafts. Blood 2008, 111, 2290–2299. [Google Scholar]

- Kigel, B.; Varshavsky, A.; Kessler, O.; Neufeld, G. Successful inhibition of tumor development by specific class-3 semaphorins is associated with expression of appropriate semaphorin receptors by tumor cells. PLoS One 2008, 3, e3287. [Google Scholar]

- Maione, F.; Molla, F.; Meda, C.; Latini, R.; Zentilin, L.; Giacca, M.; Seano, G.; Serini, G.; Bussolino, F.; Giraudo, E. Semaphorin 3A is an endogenous angiogenesis inhibitor that blocks tumor growth and normalizes tumor vasculature in transgenic mouse models. J. Clin. Invest. 2009, 119, 3356–3372. [Google Scholar]

- Casazza, A.; Fu, X.; Johansson, I.; Capparuccia, L.; Andersson, F.; Giustacchini, A.; Squadrito, M.L.; Venneri, M.A.; Mazzone, M.; Larsson, E.; et al. Systemic and targeted delivery of semaphorin 3A inhibits tumor angiogenesis and progression in mouse tumor models. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, C.; Xiang, R.H.; Bracht, T.; Naylor, S.L. Human Semaphorin 3B (SEMA3B) located at chromosome 3p21.3 suppresses tumor formation in an adenocarcinoma cell line. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 542–546. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Rivera, E.; Ran, S.; Thorpe, P.; Minna, J.D. Semaphorin 3B (SEMA3B) induces apoptosis in lung and breast cancer, whereas VEGF165 antagonizes this effect. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 11432–11437. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Rivera, E.; Ran, S.; Brekken, R.A.; Minna, J.D. Semaphorin 3B inhibits the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway through neuropilin-1 in lung and breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 8295–8303. [Google Scholar]

- Rolny, C.; Capparuccia, L.; Casazza, A.; Mazzone, M.; Vallario, A.; Cignetti, A.; Medico, E.; Carmeliet, P.; Comoglio, P.M.; Tamagnone, L. The tumor suppressor semaphorin 3B triggers a prometastatic program mediated by interleukin 8 and the tumor microenvironment. J. Exp. Med. 2008, 205, 1155–1171. [Google Scholar]

- Brambilla, E.; Constantin, B.; Drabkin, H.; Roche, J. Semaphorin SEMA3F localization in malignant human lung and cell lines: A suggested role in cell adhesion and cell migration. Am. J. Pathol. 2000, 156, 939–950. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, R.; Davalos, A.R.; Hensel, C.H.; Zhou, X.J.; Tse, C.; Naylor, S.L. Semaphorin 3F gene from human 3p21.3 suppresses tumor formation in nude mice. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 2637–2643. [Google Scholar]

- Kusy, S.; Nasarre, P.; Chan, D.; Potiron, V.; Meyronet, D.; Gemmill, R.M.; Constantin, B.; Drabkin, H.A.; Roche, J. Selective suppression of in vivo tumorigenicity by semaphorin SEMA3F in lung cancer cells. Neoplasia 2005, 7, 457–465. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, O.; Shraga-Heled, N.; Lange, T. Semaphorin-3F is an inhibitor of tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 1008–1015. [Google Scholar]

- Bielenberg, D.R.; Hida, Y.; Shimizu, A.; Kaipainen, A.; Kreuter, M.; Choi, K.C.; Klagsbrun, M. Semaphorin 3F, a chemorepulsant for endothelial cells, induces a poorly vascularized, encapsulated, nonmetastatic tumor phenotype. J. Clin. Invest. 2004, 114, 1260–1268. [Google Scholar]

- Chabbert-de Ponnat, I.; Buffard, V.; Leroy, K.; Bagot, M.; Bensussan, A.; Wolkenstein, P.; Marie-Cardine, A. Antiproliferative effect of semaphorin 3F on human melanoma cell lines. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2006, 126, 2343–2345. [Google Scholar]

- Nasarre, P.; Kusy, S.; Constantin, B. Semaphorin SEMA3F has a repulsing activity on breast cancer cells and inhibits E-cadherinmediated cell adhesion. Neoplasia 2005, 7, 180–189. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, C.; Ambartsumian, N.; Gilestro, G.; Thomsen, B.; Comoglio, P.; Tamagnone, L.; Guldberg, P.; Lukanidin, E. Proteolytic processing converts the repelling signal Sema3E into an inducer of invasive growth and lung metastasis. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 6167–6177. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, H.; Wanami, L.S.; Dissanayake, T.R.; Bachelder, R.E. Autocrine semaphorin3A stimulates alpha2 beta1 integrin expression/function in breast tumor cells. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2009, 118, 197–205. [Google Scholar]

- Nasarre, P.; Constantin, B.; Rouhaud, L. Semaphorin SEMA3F and VEGF have opposing effects on cell attachment and spreading. Neoplasia 2003, 5, 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Gluzman-Poltorak, Z.; Cohen, T.; Shibuya, M.; Neufeld, G. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 and neuropilin-2 form complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 18688–18694. [Google Scholar]

- Favier, B.; Alam, A.; Barron, P.; Bonnin, J.; Laboudie, P.; Fons, P.; Mandron, M.; Herault, J.P.; Neufeld, G.; Savi, P. Neuropilin-2 interacts with VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-3 and promotes human endothelial cell survival and migration. Blood 2006, 108, 1243–1250. [Google Scholar]

- Caunt, M.; Mak, J.; Liang, W.C.; Stawicki, S.; Pan, Q.; Tong, R.K.; Kowalski, J.; Ho, C.; Reslan, H.B.; Ross, J.; et al. Blocking neuropilin-2 function inhibits tumor cell metastasis. Cancer Cell 2008, 13, 331–342. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Yuan, L.; Mak, J.; Pardanaud, L.; Caunt, M.; Kasman, I.; Larrivée, B.; Del Toro, R.; Suchting, S.; Medvinsky, A.; et al. Neuropilin-2 mediates VEGF-C-induced lymphatic sprouting together with VEGFR3. J. Cell. Biol. 2010, 188, 115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X.L.; Sun, J.F.; Wang, X.Y.; Du, L.L.; Liu, P. Blocking neuropilin-2 enhances corneal allograft survival by selectively inhibiting lymphangiogenesis on vascularized beds. Mol. Vis. 2010, 16, 2354–2361. [Google Scholar]

- Fukasawa, M.; Matsushita, A.; Korc, M. Neuropilin-1 interacts with integrin beta1 and modulates pancreatic cancer cell growth, survival and invasion. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2007, 6, 1173–1180. [Google Scholar]

- Valdembri, D.; Caswell, P.T.; Anderson, K.I.; Schwarz, J.P.; König, I.; Astanina, E.; Caccavari, F.; Norman, J.C.; Humphries, M.J.; Bussolino, F.; Serini, G. Neuropilin-1/GIPC1 signaling regulates alpha5beta1 integrin traffic and function in endothelial cells. PLoS Biol. 2009, 7, e1000025. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, S.D.; Reynolds, L.E.; Kostourou, V.; Reynolds, A.R.; da Silva, R.G.; Tavora, B.; Baker, M.; Marshall, J.F.; Hodivala-Dilke, K.M. Alphav beta3 integrin limits the contribution of neuropilin-1 to vascular endothelial growth factor-induced angiogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 33966–33981. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, B.; Guo, P.; Bar-Joseph, I.; Imanishi, Y.; Jarzynka, M.J.; Bogler, O.; Mikkelsen, T.; Hirose, T.; Nishikawa, R.; Cheng, S.Y. Neuropilin-1 promotes human glioma progression through potentiating the activity of the HGF/SF autocrine pathway. Oncogene 2007, 26, 5577–5586. [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita, A.; Götze, T.; Korc, M. Hepatocyte growth factor-mediated cell invasion in pancreatic cancer cells is dependent on neuropilin-1. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 10309–10316. [Google Scholar]

- Glinka, Y.; Prud'homme, G.J. Neuropilin-1 is a receptor for transforming growth factor beta-1, activates its latent form, and promotes regulatory T cell activity. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2008, 84, 302–310. [Google Scholar]

- Glinka, Y.; Stoilova, S.; Mohammed, N.; Prud'homme, G.J. Neuropilin-1 exerts coreceptor function for TGF-beta-1 on the membrane of cancer cells and enhances responses to both latent and active TGF-beta. Carcinogenesis 2010, 32, 613–621. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, S.; Yaqoob, U.; Das, A.; Shergill, U.; Jagavelu, K.; Huebert, R.C.; Routray, C.; Abdelmoneim, S.; Vasdev, M.; Leof, E.; et al. Neuropilin-1 promotes cirrhosis of the rodent and human liver by enhancing PDGF/TGF-beta signaling in hepatic stellate cells. J. Clin. Invest. 2010, 120, 2379–2394. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Szabolcs, A.; Dutta, S.K.; Yaqoob, U.; Jagavelu, K.; Wang, L.; Leof, E.B.; Urrutia, R.A.; Shah, V.H.; Mukhopadhyay, D. Neuropilin-1 mediates divergent R-Smad signaling and the myofibroblast phenotype. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 31840–31848. [Google Scholar]

- Grandclement, C.; Bedel, R.; Kantelip, B.; Bouard, A.; Mougey, V.; Klagsbrun, M.; Ferrand, C.; Tiberghien, P.; Pivot, X.B.; Borg, C. Neuropilin-2 and epithelial to mesenchymal transition in colorectal cancer cells. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28. Abstract 10628. [Google Scholar]

- Guarino, M. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and tumour invasion. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007, 39, 2153–2160. [Google Scholar]