Nerve Growth Factor in Cancer Cell Death and Survival

Abstract

: One of the major challenges for cancer therapeutics is the resistance of many tumor cells to induction of cell death due to pro-survival signaling in the cancer cells. Here we review the growing literature which shows that neurotrophins contribute to pro-survival signaling in many different types of cancer. In particular, nerve growth factor, the archetypal neurotrophin, has been shown to play a role in tumorigenesis over the past decade. Nerve growth factor mediates its effects through its two cognate receptors, TrkA, a receptor tyrosine kinase and p75NTR, a member of the death receptor superfamily. Depending on the tumor origin, pro-survival signaling can be mediated by TrkA receptors or by p75NTR. For example, in breast cancer the aberrant expression of nerve growth factor stimulates proliferative signaling through TrkA and pro-survival signaling through p75NTR. This latter signaling through p75NTR promotes increased resistance to the induction of cell death by chemotherapeutic treatments. In contrast, in prostate cells the p75NTR mediates cell death and prevents metastasis. In prostate cancer, expression of this receptor is lost, which contributes to tumor progression by allowing cells to survive, proliferate and metastasize. This review focuses on our current knowledge of neurotrophin signaling in cancer, with a particular emphasis on nerve growth factor regulation of cell death and survival in cancer.1. Introduction

Understanding the processes that regulate cell death and survival is essential for the development of therapeutic strategies for the treatment of cancer. In this regard, targeting growth factors has particular significance. Here we discuss evidence regarding the role of nerve growth factor (NGF), the first growth factor discovered, in cancer biology with particular focus on its role in the death and survival of cancer cells.

The balance between cell death and survival in an organism is key to maintaining tissue homeostasis. Cancers can arise as a result of many changes in the behavior of cells, one of which is their prolonged survival beyond normal limits, or their acquired ability to evade cell death in the face of stresses that would lead to the death and removal of a normal cell [1]. Some of the cell death pathways that are affected include apoptotic responses and autophagy. Apoptosis is a term coined in 1972 to describe a naturally occurring programmed cell death mechanism [2]. As well as its induction by cytotoxic stimuli, apoptosis normally helps to maintain a constant cell number in multicellular organisms. Some of the morphological characteristics of apoptotic cell death include cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation, nuclear fragmentation, membrane blebbing, formation of apoptotic bodies and finally, disposal of cellular debris by phagocytes. These steps are highly controlled and executed in an ordered fashion [3]. The morphological characteristics of apoptosis are largely mediated by caspases, a family of cysteine-dependent aspartic acid specific proteases, which cleave many different proteins to bring about controlled cell death [4,5]. These are activated in a cascade, with initiator caspases activating downstream effector caspases through proteolysis [4]. Autophagy can act as both a pro-survival and pro-death process in multicellular organisms. It is a normal response to nutrient deprivation and certain other stresses whereby cells initiate auto-digestion pathways to release alternative sources of energy and promote cell survival. However, excessive autophagy is linked to cell death and is sometimes called autophagic cell death [6,7]. Autophagic cell death can be utilized when apoptotic pathways are inaccessible [8-10]. Autophagic cell death is caspase-independent [11,12]. It involves engulfment of cellular components and organelles into double-membraned vesicles called autophagosomes which fuse with lysosomes to produce autophagolysosomes, where the contents are subsequently degraded [7,13].

Many growth factors and cytokines are important for cell death and survival signaling, and dysregulation of growth factor signaling often plays an important role in cancer development [1]. Moreover, progression of cancer, including development of metastasis and angiogenesis of tumors, is often found to be linked to altered expression of growth factors and their receptors, many of which are known oncogenes and tumor suppressors [14]. NGF is one such protein and during recent years, NGF signaling has been shown to alter cell death and survival in various cancer cells. Here we will describe the role of NGF in cell death and survival signaling with a particular focus on breast and prostate cancers, since most advances in this area have been made in these cancers.

2. Neurotrophins and Nerve Growth Factor (NGF)

The discovery by Rita Levi-Montalcini in the 1940s of the first growth factor pioneered the field of growth factor research. She identified NGF as a substance secreted from mouse sarcoma tissue that stimulated neuronal survival and neurite outgrowth from chicken ganglia. This provided some of the first evidence of paracrine signaling, whereby cells in one tissue secreted a protein which readily diffused to another tissue to elicit cellular changes in the target tissue [15]. NGF is the prototypic member of the small family of neurotrophins, which also includes brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), neurotrophin-3 (NT-3) and NT-4/5 [16,17]. The history of NGF and neurotrophin research is tightly woven into the field of neuroscience, where NGF has been shown to promote survival and differentiation of neurons, outgrowth of neurites, while BDNF is also involved in learning and memory [18-20]. A critical role for neurotrophins in development of the nervous system has been revealed by gene targeting in the mouse [21-23]. However, it is pertinent here to remember that NGF was first shown to be secreted from mouse sarcoma tissue and that neurotrophins are expressed in many areas of the body and frequently participate in signaling beyond the nervous system [18]. In fact, the non-neural functions of NGF have gained significant attention in recent years and NGF has been shown to have roles in development of the male and female reproductive systems, the endocrine, cardiovascular and immune systems [21]. It is recognized that dysregulation of neurotrophin signaling plays important roles in the pathogenesis of many tumors including several of non-neural origin [14,24]. In these cancers, NGF and other neurotrophins regulate cell proliferation and invasion as well as cell death and survival. These various responses are dependent on cell type and often reflect the expression of receptors and adaptor proteins by the cells.

2.1. Neurotrophin Receptors

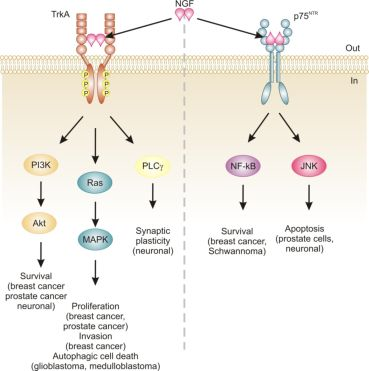

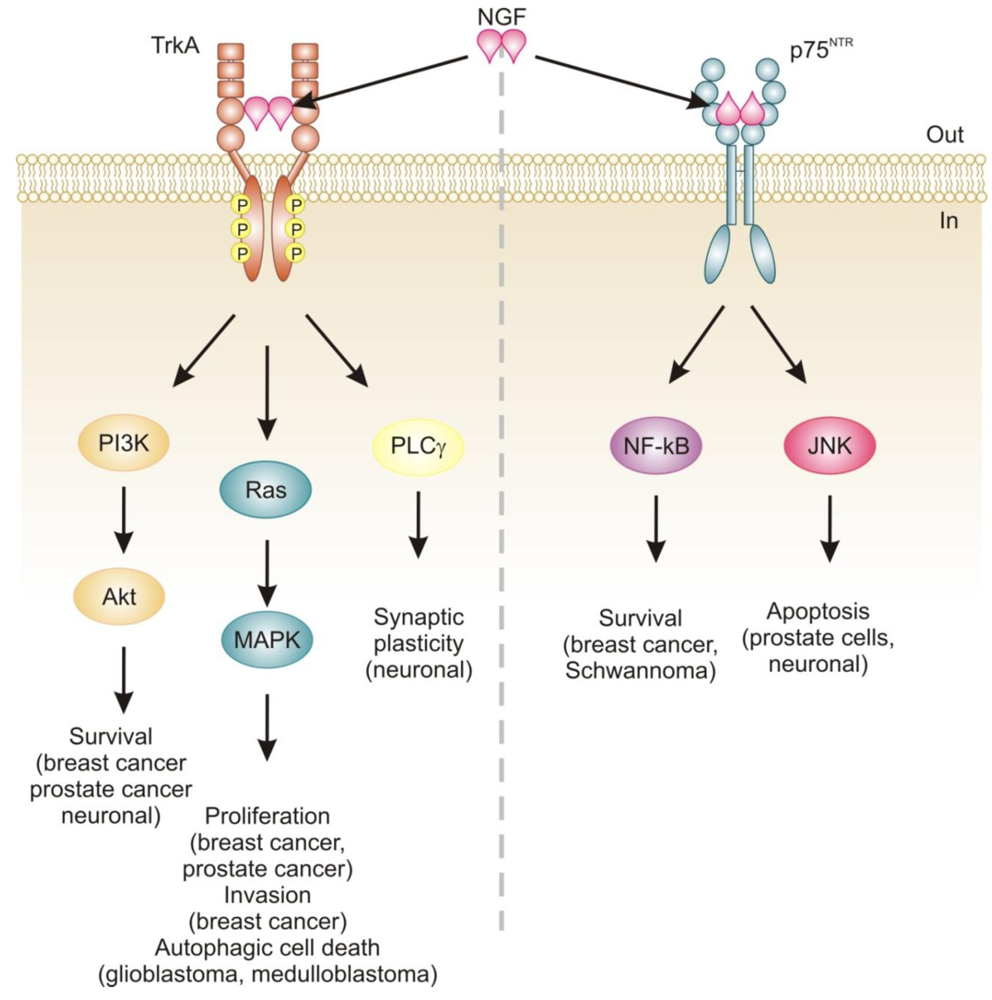

Neurotrophins mediate their diverse functions through two structurally distinct classes of transmembrane receptors; the ‘common’ p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR) which binds all of the neurotrophins with approximately equal affinity, and specific receptor tyrosine kinase receptors called tropomyosin related kinases (Trks) that exhibit specificity in neurotrophin binding (Figure 1) [18,25].

p75NTR is a member of the death-promoting tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNF-R) superfamily, which also includes the characteristic death receptors TNF-R apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-R and Fas/CD95 [26,27]. p75NTR is a 75 kDa glycoprotein with four extracellular cysteine rich repeats required for ligand binding [28,29]. It is a single pass type I transmembrane receptor, with an intracellular domain containing a juxtamembrane region and a type II consensus death domain (DD) sequence [18]. Although p75 binds dimeric neurotrophin ligands, there is some controversy over the oligomeric status of p75 and evidence indicates that it may signal as a monomer or as a dimer [30]. Recently, it was shown that p75 can form covalent homodimers through a disulphide bond in the transmembrane region. In this case, neurotrophin binding is understood to induce a conformational change in the receptor, such that it pivots on this disulfide bond at Cys257 to permit access of intracellular adaptor proteins to the intracellular domain in what is termed a snail-tong model [30-32]. The receptor does not possess intrinsic enzymatic activity and transduces signals through recruitment of a variety of adaptor proteins to the intracellular domain, leading to proliferation, survival, or cell death [18,33]. p75NTR-mediated downstream signal transduction pathways are extremely diverse, being heavily dependent on the cell context, availability of intracellular adaptor molecules and expression of interacting transmembrane co-receptors [34]. Interestingly, p75NTR also serves as a receptor for immature pro-neurotrophins which induce cell death in a manner that is dependent on binding to a co-receptor, sortilin [35]. Furthermore, p75NTR is capable of eliciting cellular signals in the absence of bound ligand [31]. p75NTR signaling can also lead to downstream activation of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) which promotes cell survival through upregulation of anti-apoptotic genes such as cFLIP, which interferes with the activation of initiator caspase-8, the Bcl-2 family member Bcl-XL, and inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) XIAP and cIAP1/2 [36-38]. Together with the pro-apoptotic effects of p75, these findings show that p75NTR can act as a bifunctional switch directing the cell down opposing paths of cell death or survival.

There is a wide array of proteins that have been demonstrated to interact with the intracellular domain of p75NTR. These include neurotrophin receptor-interacting MAGE homolog (NRAGE), p75NTR-associated cell death executor (NADE) and neurotrophin receptor-interacting factor (NRIF), which are all involved in mediating pro-apoptotic effects; FAP-1, receptor interacting protein 2 (RIP2) and tumor necrosis factor receptor associated factor 6 (TRAF6), which are involved in mediating pro-survival effects, while Schwann cell factor-1 (SC-1) is involved in mediating cell cycle effects and RhoA affects neuritogenesis [18]. In addition, p75 has been reported to interact with other TRAF family members, particularly TRAF2 and TRAF4, eliciting different effects on NF-κB activation and apoptosis [39].

Trk receptors are structurally unrelated to p75NTR and are receptor tyrosine kinases [40]. In contrast to p75NTR, Trk receptors are selective in which neurotrophins they will bind, with TrkA preferring NGF, TrkB preferring BDNF and NT-4/5 and TrkC preferring NT-3 [40]. Binding of their dimeric ligands induces receptor homodimerization and trans-autophosphorylation in the intracellular domain leading to activation of three well characterized intracellular signal transduction pathways, including Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt and phospholipase Cγ (PLCγ) [28,41]. These pathways are best studied in neuronal cells, where they are involved in neuronal growth, survival and differentiation [40]. In non-neuronal cells, activation of Trk receptors is linked to proliferation, survival, migration and increased invasiveness of cancer cells (Figure 1) [42,43].

In addition, TrkA signaling has also been linked to induction of autophagy in cancer cells. For example, autophagy was identified as a novel mechanism of NGF-induced cell death via TrkA in the human glioblastoma cell line, G55 [44]. Several characteristics of autophagy were observed, including autophagic vacuoles, acidic vesicular organelles (which could be prevented by bafilomycin A1), increased processing of LC3, lack of detection of caspase activation, and vacuolation was prevented by the autophagy inhibitor 3-methyladenine [44]. The authors also found that activation of ERK and c-Jun N-terminal kinase, but not p38, were involved in autophagic vacuolation [44]. Very recently, TrkA has been shown to induce cell death in medulloblastoma Daoy cells without caspase activation and demonstrating several clear signs of autophagy [45]. However, siRNA silencing of four proteins essential to autophagy (beclin-1, Atg5, LC3 and Atg9) neither blocked NGF-induced vacuole formation or cell death [45]. Instead, the authors revealed that it is the hyperstimulation of macropinocytosis, a form of bulk fluid endocytosis [46], that is responsible for their death and that it requires TrkA-dependent activation of casein kinase 1 [45]. In both of these studies, TrkA was ectopically expressed in the cells. In fact, a series of studies by Kim and colleagues demonstrates that overexpression of TrkA in U20S osteosarcoma and SK-N-MC neuroblastoma cells induces cell death even in the absence of NGF and that, at least in U2OS, a large portion of this cell death is caused by induction of autophagy [47]. Together, these studies suggest that TrkA expression might confer a growth disadvantage to certain cancerous cells, such as glioblastoma [44], medulloblastoma [45] and osteosarcoma [47]. However, further research is required to ascertain the precise mode of death. Nevertheless, TrkA activation may potentially provide a therapeutic avenue, particularly as several current chemotherapeutics also induce autophagic cell death, e.g., [48].

3. NGF Signaling in Cancers

The relevance of neurotrophins to tumor biology is not well-characterized, although there are clear links: NGF was originally purified from a sarcoma, TrkA was discovered in a human colon carcinoma biopsy and p75NTR was purified from a human melanoma cell line [49-51]. Altered neurotrophin signaling has since been implicated in the development and progression of a number of cancers, including neuroblastoma, medulloblastoma, melanoma, papillary thyroid carcinoma, pancreatic cancer, prostate cancer, and breast cancer (Table 1) [14]. Neurotrophin signaling in the pathogenesis of cancer has been linked to stimulation of mitogenesis, promotion of metastasis and invasiveness, and inhibition of apoptosis (Figure 1) [14,52-54]. Breast cancer and prostate cancer are notable because there is a large body of evidence demonstrating how NGF in particular is involved in disease development and progression [52,53]. In addition, neurotrophin signaling in these two cancers provides an example of how the same ligand/receptor interactions can stimulate different cellular outcomes depending on the cell type. Here we will discuss the current literature regarding the role of NGF in cell death and survival signaling in breast and prostate cancers.

3.1. NGF and Breast Cancer

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy in women, and is a major cause of cancer-related death in women, second in mortality only to lung cancer [80]. Advances in understanding of the disease, and development of therapeutics targeting estrogen and epidermal growth factor signaling, correlate with a notable reduction in breast cancer mortality levels during the past 10 years, with adjuvant chemotherapeutic agents such as anthracyclines, taxanes and cyclophosphamides also becoming intrinsic to cancer treatment regimes. Normal breast epithelial cells express TrkA and p75NTR [55]. The function of these receptors in breast development and physiology has not been studied and in fact, ligands for these receptors are not normally expressed by adult breast cells, although it is not clear whether the receptors are activated by NGF secreted in a paracrine fashion. In contrast, breast tumors have been shown to express NGF. For example, immunohistochemical analysis has shown that NGF is expressed in up to 80% of breast cancer tumor biopsies [81]. This expression does not discriminate between breast tumor subtype and NGF mRNA levels are expressed at levels comparable to those seen in the MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell line [81]. In another study, investigation of the expression of NGF and its receptors in breast cancer cells in effusions and solid tumors revealed that activated TrkA (i.e., phosphorylated TrkA) is upregulated in effusions compared to primary breast tumors and lymph node metastasis, with downregulation of p75 in effusions [82]. Another recent immunohistochemical analysis has shown expression of NGF in fat tissue extracts from high risk patients [83]. Thus far, NGF expression has not been associated with expression of any known prognostic factor, such as estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR) or human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). Anti-estrogens such as tamoxifen are used in approximately two thirds of breast cancers, while HER2 is overexpressed in 25–30% of human metastatic breast cancers [84]. Since NGF is expressed in 80% of breast cancers, this suggests that NGF signaling has a potentially broader target range than current therapies, which are directed against either estrogen signaling or HER2. Importantly, NGF can stimulate mitogenesis and pro-survival signaling in triple negative breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231) which lack ER, PR and HER2 and are the most difficult type of breast tumor to treat [42]. Importantly, a xenograft model of breast cancer using MDA-MB-231 cells is responsive to anti-NGF treatments, including antibody and siRNA downregulation of NGF [81].

NGF signaling has been implicated in the proliferation and survival of breast cancer cells and more recently, migration [42,43,85]. The proliferative effect is via TrkA signaling and can be inhibited by tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as the indolocarbazole K252a [42]. Interestingly, tamoxifen has also been reported to inhibit NGF mediated TrkA phosphorylation in an estrogen receptor-independent manner [86]. TrkA-induced proliferation of breast cancer cells proceeds through activation of MAP kinase signaling leading to ERK phosphorylation and an NGF-dependent decrease in cell cycle duration (Figure 2) [42]. In contrast, NGF does not activate MAP kinases in normal breast epithelial cells and is not mitogenic for these cells [55]. The reason for this lack of MAP kinase activation in normal breast epithelial cells is not clear, since these cells express TrkA [55]. Recently, TrkA signaling was also shown to play a role in breast cancer metastasis and angiogenesis, which expands the role of NGF signaling in this disease [43,58].

3.2. NGF Pro-Survival Signaling in Breast Cancer Is Mediated by p75NTR

NGF exerts pro-survival effects on a wide range of breast cancer cell lines (MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, T-47D and BT-20) and can protect them from C2-ceramide induced apoptosis [42,61]. In contrast to mitogenic signaling, NGF pro-survival effects in breast cancer cells are mediated by the p75NTR receptor [42]. The precise mechanism by which NGF signaling through p75NTR protects breast cancer cells is largely unknown but functional studies have shown that it is mediated by activation of NF-κB [42]. In breast cancer cells the adaptors that link NGF/p75NTR receptor activation to NF-κB and pro-survival signaling are largely unknown. In MCF-7 cells neurotrophin-dependent recruitment of TNF-R-associated death domain (TRADD) to p75NTR has been shown to be required for activation of NF-κB and pro-survival signaling (Figure 2) [60]. Other death receptors, such as TNF-R1 and TRAIL, which recruit TRADD to their DDs, use it as a platform for the recruitment of additional adaptor proteins including receptor-interacting protein 1 (RIP1), TNF-R-associated factor 2 (TRAF2) and Fas-associated death domain (FADD) to promote either cell survival or death [87]. In fact, knockdown of TRADD causes cells to be deficient in both TNFα-induced NF-κB activation and in caspase-8-dependent apoptosis [88]. Notably, there is currently no evidence that TRADD associated with p75NTR can recruit these or other adaptors in breast cancer cells or other cells. Instead, in Schwann cells, RIP2 has been shown to interact directly with the DD of p75NTR and to stimulate pro-survival signaling through activation of NF-κB [89]. In addition, certain members of the TRAF family (TRAF2, 4, 6) have been reported to interact directly with the p75NTR intracellular domain [39,90-92]. The role of TRAF proteins in p75NTR-mediated pro-survival signaling in breast cancer is not known and may be an avenue worthy of investigation.

In breast cancer cells, a novel adaptor Bex2 has recently been shown to be required for NGF/p75NTR-dependent NF-κB activation and prosurvival effects (Figure 2) [61,63]. BEX2 is a 15 kDa protein which is over-expressed in ER-positive breast cancer cells and is suggested to be an estrogen-regulated gene [61]. Although it has not been shown whether or not BEX2 interacts directly with p75NTR, it is reported to be necessary and sufficient for the anti-apoptotic function of NGF in breast cancer cells [61,62]. Furthermore, it has been shown to protect breast cancer cells from mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis, through modulation of Bcl-2 family member proteins, including up-regulation of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 and down-regulation of pro-apoptotic members Bad, Bak and PUMA [62]. Interestingly, the homologues BEX1 and BEX3 have also been shown to interact with p75NTR, and in neural tissues BEX1 inhibits NF-κB, links neurotrophin signaling to the cell cycle and may sensitize cells to apoptosis [93,94]. BEX2 has also been shown to be required for progression of MCF-7 breast cancer cells through the G1 phase of the cell cycle via its regulation of cyclin D1 and p21 [62,63].

3.3. Neurotrophin Signaling in Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed solid tumor in men and the second leading cause of male cancer related deaths [80]. Its incidence significantly increases with age, regardless of variables such as diet, occupation and life style [95]. The normal adult prostate is composed of ducts with epithelial cells associated with stromal cells. The epithelial cells are of three types; secretory luminal cells which line the lumen of the duct and are surrounded by a continuous layer, formed mainly by basal epithelial cells and a scattering of neuroendocrine cells. The stroma is separated from the epithelial cells by the basal lamina, and is mainly composed of smooth muscle cells. In human prostate cancer, there is progressive disorganization of luminal and basal epithelial cells, leading to breakdown of the basal lamina and eventual metastasis of the cells to other body sites [54]. While the tumor cells are initially dependent on androgen for their survival, this dependence is progressively lost leading to development of resistance to androgen-targeting therapies. Interestingly, the secretory luminal cells are androgen-sensitive, while the basal epithelial cells express low levels of androgen receptor and the neuroendocrine cells are androgen insensitive, [54].

After the central nervous system the human prostate is the next most abundant source of NGF [96], where it plays a role in normal prostate development [97]. Stromal cells secrete NGF which binds to TrkA and p75NTR present on prostate epithelial cells stimulating their growth [98-100]. It is of interest to note that BDNF, which can bind to p75NTR, has also been shown to be expressed by normal prostate stromal cells [101].

Progression of prostate cancer is accompanied by modifications in the expression of neurotrophins, including NGF, and neurotrophin receptors [95,102]. The most striking and important change in this regard is a reduction in p75NTR expression by the epithelial cells [73]. While there is no change in the expression of NGF or TrkA, the epithelial layer exhibits a reduction in p75NTR expression [73]. Immunocytochemical staining of both normal and malignant prostate epithelial tissue shows progressive loss of p75NTR expression is associated with tumor development [98]. Importantly, the loss of p75NTR is directly related to the grade of malignancy with early stages (prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia) still showing p75NTR, and poorly differentiated carcinomas having undetectable levels [103]. This is also seen in prostate cancer cell lines, where p75NTR is absent from cell lines derived from advanced metastatic prostate cancer [73,74,98]. These studies also show that TrkA receptor expression is unchanged, resulting in an overall decrease in the p75NTR:TrkA ratio during prostate cancer progression. This is also accompanied by an increase in the in vitro invasive capacity of human prostatic cancer cells in xenograft models [104]. This has been reported to involve increased expression of heparanase [103]. In contrast, the mitogenic action of NGF on prostate cancer lines is mediated by TrkA [105].

There is also some evidence to suggest that during progression of prostate cancer epithelial cells acquire the ability to express neurotrophins [101]. For example, the non-metastatic LNCaP cell line does not express neurotrophins, while metastatic lines DU145 and PC-3 secrete measurable amounts of NGF [99,104] and PC-3 secretes both NGF and BDNF [99]. This switch from paracrine to autocrine control of neurotrophin activity, as well as loss of p75NTR, could facilitate survival and proliferation of these cells upon metastasis to other regions of the body.

This acquired ability of prostatic cancer cells to evade cell death has lead to p75NTR being proposed as a tumor suppressor in prostate cancer cells [71,72,106]. In the absence of p75NTR, prostatic cancer cells respond to proliferative signals mediated by TrkA activation and proliferate. In fact, treatment of prostate tumor cells with pharmacological inhibitors of TrkA signaling, including K252a and CEP-701, reduces proliferation induced by NGF and leads to increased cell death [107,108]. When p75NTR is artificially reintroduced into prostate cancer cells, the cells exhibit cell cycle arrest, accumulating in S phase, and undergo an increase in spontaneous apoptosis [71,105,109]. The mechanism of induction of apoptosis by NGF/p75NTR has not been fully elucidated. However, reintroduction of p75NTR expression into PC-3 cells is accompanied by a decrease in activation of NF-κB and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), suggesting these signals mediate the anti-apoptotic effect in the absence of p75NTR [110]. Although pro-apoptotic signaling by p75NTR in prostate cells requires the DD [71], it does not involve activation of initiator caspases-8 or -10 which are activated by other death receptors such as TNF-R, TRAIL receptors and Fas [111,112].

The loss of p75NTR in prostate cancer does not appear to be due to errors or mutations in the genetic transcript coding for p75NTR. Rather, it has been linked to instability of the mRNA, which may be due to changes in the 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) of the p75NTR gene [73]. The 3′-UTR of genes generally contains several regulatory sequences involved in poly-adenylation, mRNA stability and binding sites for micro-RNAs (miRNAs) which are involved in controlling mRNA stability and translation [113,114]. Thus, for example, it is possible that enhanced expression of miRNAs that target the 3′-UTR of p75NTR could be responsible for downregulation of expression of the protein. Interestingly, gonadotrophin releasing hormone (GnRH) analogue therapy induces a significant increase in p75NTR protein expression (with no increase in TrkA expression) [115], prompting the question as to whether GnRH analogue increases the stability of p75NTR mRNA.

4. NGF Signaling as a Therapeutic Target in Cancer

Our knowledge of NGF signaling in various cancers suggest therapeutic opportunities. For example, in breast cancer therapies aimed at interfering with NGF/p75NTR pro-survival signaling could increase effectiveness of cyto/genotoxic drugs used as adjuvant therapies in breast cancer treatment, thus lowering the dose required and reducing side effects associated with this adjuvant therapy. This is important because current combination therapies often produce unwanted side effects, e.g., doxorubicin can cause myelosuppression and cardiomyopathies [116].

NGF signaling can be targeted in a number of ways, the most common methods employ mechanisms to interfere with NGF binding to its receptors or with subsequent activation of the receptors. In prostate cancer, where the p75NTR receptor is lost, there is emphasis on inhibition of TrkA proliferative signaling. In fact, strategies that are aimed at inhibiting NGF signaling are already in clinical trials for the treatment of prostate cancer [117]. In this context, pharmacological inhibitors of Trk signaling, such as derivatives of the pan-Trk inhibitor K252a, have proven interesting. One such compound, CEP-701, has been reported to block the invasive capability of prostate cancer cells in vivo [118]. The oral homologue, CEP-751, has been reported to induce apoptotic death of malignant cells, to decrease metastasis and to enhance host survival in in vivo experimental models of prostate cancer [119,120].

Small molecule inhibitors of p75NTR signaling have also been produced [121]. Pep-5 is an 11 amino acid peptide that targets the intracellular domain of p75NTR and inhibits it [122]. It is available as a Tat-fusion peptide which facilitates cellular entry. Also of interest are Ro-08 2750 and PD90780, small molecules that interact with NGF and prevent its binding to p75NTR, have proved useful in some research settings [123,124]. Thus far, these have not been fully investigated as a potential basis for therapeutic inhibition of NGF binding to p75NTR.

In a xenograft model of breast cancer, antibodies against NGF were successful in reducing tumor growth. This suggests that anti-NGF antibody therapies may prove useful in the treatment of breast cancer where overexpression of NGF is a factor. Furthermore, anti-NGF antibodies have been shown to reduce cell migration by up to 40% in two prostate cancer cell lines (DU-145 and PC-3), which have lost expression of p75NTR and retained TrkA tyrosine kinase activity [125]. Of relevance to this point is Tanezumab, a humanized recombinant anti-NGF. Tanezumab reached Phase III clinical trials, proving highly effective at blocking pain perception in patients with chronic pain from osteoarthritis of the knee [126]. Although the trial was prematurely halted in June 2010, because some participants presented with increased damage to joints, it has been suggested that the reason for these adverse effects was excessive use of the joints as a result of lack of pain sensation [127].

Rapid advances in drug design, particularly rational design, make it likely that other approaches will be used to interfere with aberrant NGF/TrkA/p75NTR signaling in cancers. For example, the development of small molecules to interfere with protein:protein interactions or of antibodies to target receptors may prove useful in treatment of these diseases. Furthermore, it is likely that new revelations regarding regulators of protein expression, such as miRNAs, or epigenetic modulators such as histone deacetylase inhibitors and DNA methyltransferase inhibitors, will reveal novel ways to target aberrant signaling due to altered expression of culprit proteins in cancers.

| Tissue type | Dysregulation in NGF signaling | Cellular response | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-neuronal carcinomas | |||

| Breast | Gain in NGF expression via autocrine and possibly paracrine mechanisms | TrkA signaling increased leading to proliferation, mitogenesis, invasion, metastasis, angiogenesis by activating MAPK, PI3K/Akt and PLCγ | [43,55-59] |

| p75NTR signaling leading to activation of NF-κB and increased survival of breast cancer cells | [42,60-63] | ||

| Melanoma | NGF-mediated paracrine signaling | NGF acts as a cytostatic or differentiation factor, promoting proliferation, migration and invasion of melanoma cells. | [64-66] |

| Malignant melanoma cells express p75NTR | Melanoma cells also express the p75NTR co-receptor sortilin which with pro-NGF stimulates migration | [66] | |

| Pancreatic | NGF expression is increased | NGF enhances proliferation invasion and tumorigenicity | [67,68] |

| Papillary thyroid carcinoma | Fusion of TrkA gene with various activating genes | Forms a chimeric receptor which displays constitutive activity, leading to transformation of cells | [69,70] |

| Prostate | Loss of p75NTR protein in basal epithelial cells due to mRNA instability leading to imbalance of TrkA:p75NTR ratio | p75NTR proposed to be a tumor suppressor in prostate cells, so its loss facilitates survival, proliferation and metastasis of tumor cells | [71-75] |

| Neuronal carcinomas | |||

| Neuroblastoma | Expression of different TrkA isoforms can have differing prognosis. | TrkA III isoform which is constitutively actively promotes survival via PI3K-AKT with resulting negative effects on prognosis. | [76] |

| Expression of full length TrkA has positive prognosis in neuroblastoma patients. | [77] | ||

| p75NTR can induce apoptosis in neuroblastoma cell lines | NGF can induce apoptosis via p75NTR in a human neuroblastoma cell line, seen with an increase in NF-κB p65 activity | [78] | |

| Glioblastoma | TrkA | Induction by NGF of autophagic cell death | [44] |

| Medulloblastoma | TrkA expression has good prognosis | NGF/TrkA signaling is found to correlate with apoptotic index in primary samples. NGF induces massive apoptosis in medulloblastoma cell lines expressing TrkA | [77,79] |

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge financial support from the Breast Cancer Campaign. We would also like to thank Sandra Healy for helpful comments.

References

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell 2000, 100, 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, J.F.; Wyllie, A.H.; Currie, A.R. Apoptosis: A basic biological phenomenon with wide- ranging implications in tissue kinetics. Br. J. Cancer 1972, 26, 239–257. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, R.C.; Cullen, S.P.; Martin, S.J. Apoptosis: Controlled demolition at the cellular level. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008, 9, 231–241. [Google Scholar]

- Luthi, A.U.; Martin, S.J. The CASBAH: A searchable database of caspase substrates. Cell Death Differ. 2007, 14, 641–650. [Google Scholar]

- Lamkanfi, M.; Declercq, W.; Depuydt, B.; Kalai, M.; Saelens, X.; Vandenabeele, P. The caspase family. In Caspases: Their Role in Cell Death and Cell Survival; Los, M., Walczak, H., Eds.; Landes Bioscience, Kluwer Academic Press: New York NY, USA, 2003; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Galluzzi, L.; Vicencio, J.M.; Kepp, O.; Tasdemir, E.; Maiuri, M.C.; Kroemer, G. To die or not to die: That is the autophagic question. Curr. Mol. Med. 2008, 8, 78–91. [Google Scholar]

- Gozuacik, D.; Kimchi, A. Autophagy and cell death. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2007, 78, 217–245. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, L.; Fletcher, G.C.; Tolkovsky, A.M. Autophagy is activated by apoptotic signalling in sympathetic neurons: An alternative mechanism of death execution. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 1999, 14, 180–198. [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu, S.; Kanaseki, T.; Mizushima, N.; Mizuta, T.; Arakawa-Kobayashi, S.; Thompson, C.B.; Tsujimoto, Y. Role of Bcl-2 family proteins in a non-apoptotic programmed cell death dependent on autophagy genes. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004, 6, 1221–1228. [Google Scholar]

- Canu, N.; Tufi, R.; Serafino, A.L.; Amadoro, G.; Ciotti, M.T.; Calissano, P. Role of the autophagic-lysosomal system on low potassium-induced apoptosis in cultured cerebellar granule cells. J. Neurochem. 2005, 92, 1228–1242. [Google Scholar]

- Lockshin, R.A.; Zakeri, Z. Apoptosis, autophagy, and more. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2004, 36, 2405–2419. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, B.; Yuan, J. Autophagy in cell death: An innocent convict? J. Clin. Invest. 2005, 115, 2679–2688. [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky, D.J.; Abeliovich, H.; Agostinis, P.; Agrawal, D.K.; Aliev, G.; Askew, D.S.; Baba, M.; Baehrecke, E.H.; Bahr, B.A.; Ballabio, A.; et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy in higher eukaryotes. Autophagy 2008, 4, 151–175. [Google Scholar]

- Kruttgen, A.; Schneider, I.; Weis, J. The dark side of the NGF family: Neurotrophins in neoplasias. Brain Pathol. 2006, 16, 304–310. [Google Scholar]

- Levi-Montalcini, R.; Hamburger, V. Selective growth stimulating effects of mouse sarcoma on the sensory and sympathetic nervous system of the chick embryo. J. Exp. Zool. 1951, 116, 321–361. [Google Scholar]

- Angeletti, P.U.; Liuzzi, A.; Levi-Montalcini, R.; Gandiniattardi, D. Effect of a nerve growth factor on glucose metabolism by sympathetic and sensory nerve cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1964, 90, 445–450. [Google Scholar]

- Levi-Montalcini, R. The nerve growth factor. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 1964, 118, 149–170. [Google Scholar]

- Roux, P.P.; Barker, P.A. Neurotrophin signaling through the p75 neurotrophin receptor. Prog. Neurobiol. 2002, 67, 203–233. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, M.E.; Xu, B.; Lu, B.; Hempstead, B.L. New insights in the biology of BDNF synthesis and release: Implications in CNS function. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 12764–12767. [Google Scholar]

- Szegezdi, E.; Herbert, K.R.; Kavanagh, E.T.; Samali, A.; Gorman, A.M. Nerve growth factor blocks thapsigargin-induced apoptosis at the level of the mitochondrion via regulation of Bim. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2008, 12, 2482–2496. [Google Scholar]

- Tessarollo, L. Pleiotropic functions of neurotrophins in development. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1998, 9, 125–137. [Google Scholar]

- Bartkowska, K.; Turlejski, K.; Djavadian, R.L. Neurotrophins and their receptors in early development of the mammalian nervous system. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. (Wars) 2010, 70, 454–467. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, E.J.; Reichardt, L.F. Neurotrophins: Roles in neuronal development and function. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2001, 24, 677–736. [Google Scholar]

- Schor, N.F. The p75 neurotrophin receptor in human development and disease. Prog. Neurobiol. 2005, 77, 201–214. [Google Scholar]

- Schecterson, L.C.; Bothwell, M. Neurotrophin receptors: Old friends with new partners. Dev. Neurobiol. 2010, 70, 332–338. [Google Scholar]

- Haase, G.; Pettmann, B.; Raoul, C.; Henderson, C.E. Signaling by death receptors in the nervous system. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2008, 18, 284–291. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood, Z.; Shukla, Y. Death receptors: Targets for cancer therapy. Exp. Cell. Res. 316, 887–899.

- Chao, M.V. Neurotrophins and their receptors: A convergence point for many signalling pathways. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2003, 4, 299–309. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, P.A. p75NTR is positively promiscuous: Novel partners and new insights. Neuron 2004, 42, 529–533. [Google Scholar]

- Vilar, M.; Charalampopoulos, I.; Kenchappa, R.S.; Simi, A.; Karaca, E.; Reversi, A.; Choi, S.; Bothwell, M.; Mingarro, I.; Friedman, W.J.; Schiavo, G.; Bastiaens, P.I.; Verveer, P.J.; Carter, B.D.; Ibanez, C.F. Activation of the p75 neurotrophin receptor through conformational rearrangement of disulphide-linked receptor dimers. Neuron 2009, 62, 72–83. [Google Scholar]

- Simi, A.; Ibanez, C.F. Assembly and activation of neurotrophic factor receptor complexes. Dev. Neurobiol. 2010, 70, 323–331. [Google Scholar]

- Vilar, M.; Charalampopoulos, I.; Kenchappa, R.S.; Reversi, A.; Klos-Applequist, J.M.; Karaca, E.; Simi, A.; Spuch, C.; Choi, S.; Friedman, W.J.; Ericson, J.; Schiavo, G.; Carter, B.D.; Ibanez, C.F. Ligand-independent signaling by disulfide-crosslinked dimers of the p75 neurotrophin receptor. J. Cell. Sci. 2009, 122, 3351–3357. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood, C.K.; Coulson, E.J. The p75 neurotrophin receptor. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2008, 40, 1664–1668. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, B.; Pang, P.T.; Woo, N.H. The yin and yang of neurotrophin action. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2005, 6, 603–614. [Google Scholar]

- Nykjaer, A.; Lee, R.; Teng, K.K.; Jansen, P.; Madsen, P.; Nielsen, M.S.; Jacobsen, C.; Kliemannel, M.; Schwarz, E.; Willnow, T.E.; Hempstead, B.L.; Petersen, C.M. Sortilin is essential for proNGF-induced neuronal cell death. Nature 2004, 427, 843–848. [Google Scholar]

- Karin, M. Nuclear factor-kappaB in cancer development and progression. Nature 2006, 441, 431–436. [Google Scholar]

- Baud, V.; Karin, M. Is NF-kappaB a good target for cancer therapy? Hopes and pitfalls. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2009, 8, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Karin, M.; Lin, A. NF-kappaB at the crossroads of life and death. Nat. Immunol. 2002, 3, 221–227. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, X.; Mehlen, P.; Rabizadeh, S.; VanArsdale, T.; Zhang, H.; Shin, H.; Wang, J.J.; Leo, E.; Zapata, J.; Hauser, C.A.; Reed, J.C.; Bredesen, D.E. TRAF family proteins interact with the common neurotrophin receptor and modulate apoptosis induction. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 30202–30208. [Google Scholar]

- Reichardt, L.F. Neurotrophin-regulated signalling pathways. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2006, 361, 1545–1564. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, R.; Jing, S.Q.; Nanduri, V.; O'Rourke, E.; Barbacid, M. The trk proto-oncogene encodes a receptor for nerve growth factor. Cell 1991, 65, 189–197. [Google Scholar]

- Descamps, S.; Toillon, R.A.; Adriaenssens, E.; Pawlowski, V.; Cool, S.M.; Nurcombe, V.; Le Bourhis, X.; Boilly, B.; Peyrat, J.P.; Hondermarck, H. Nerve growth factor stimulates proliferation and survival of human breast cancer cells through two distinct signaling pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 17864–17870. [Google Scholar]

- Lagadec, C.; Meignan, S.; Adriaenssens, E.; Foveau, B.; Vanhecke, E.; Romon, R.; Toillon, R.A.; Oxombre, B.; Hondermarck, H.; Le Bourhis, X. TrkA overexpression enhances growth and metastasis of breast cancer cells. Oncogene 2009, 28, 1960–1970. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, K.; Wagner, B.; Hamel, W.; Schweizer, M.; Haag, F.; Westphal, M.; Lamszus, K. Autophagic cell death induced by TrkA receptor activation in human glioblastoma cells. J. Neurochem. 2007, 103, 259–275. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Macdonald, J.I.; Hryciw, T.; Meakin, S.O. Nerve growth factor activation of the TrkA receptor induces cell death, by macropinocytosis, in medulloblastoma Daoy cells. J. Neurochem. 2010, 112, 882–899. [Google Scholar]

- Araki, N.; Hamasaki, M.; Egami, Y.; Hatae, T. Effect of 3-methyladenine on the fusion process of macropinosomes in EGF-stimulated A431 cells. Cell Struct. Funct. 2006, 31, 145–157. [Google Scholar]

- Dadakhujaev, S.; Noh, H.S.; Jung, E.J.; Hah, Y.S.; Kim, C.J.; Kim, D.R. The reduced catalase expression in TrkA-induced cells leads to autophagic cell death via ROS accumulation. Exp. Cell Res. 2008, 314, 3094–3106. [Google Scholar]

- Goussetis, D.J.; Altman, J.K.; Glaser, H.; McNeer, J.L.; Tallman, M.S.; Platanias, L.C. Autophagy is a critical mechanism for the induction of the antileukemic effects of arsenic trioxide. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 29989–29997. [Google Scholar]

- Shooter, E.M. Early days of the nerve growth factor proteins. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2001, 24, 601–629. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Zanca, D.; Hughes, S.H.; Barbacid, M. A human oncogene formed by the fusion of truncated tropomyosin and protein tyrosine kinase sequences. Nature 1986, 319, 743–748. [Google Scholar]

- Marano, N.; Dietzschold, B.; Earley, J.J., Jr.; Schatteman, G.; Thompson, S.; Grob, P.; Ross, A.H.; Bothwell, M.; Atkinson, B.F.; Koprowski, H. Purification and amino terminal sequencing of human melanoma nerve growth factor receptor. J. Neurochem. 1987, 48, 225–232. [Google Scholar]

- Dolle, L.; Adriaenssens, E.; El Yazidi-Belkoura, I.; Le Bourhis, X.; Nurcombe, V.; Hondermarck, H. Nerve growth factor receptors and signaling in breast cancer. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2004, 4, 463–470. [Google Scholar]

- Arrighi, N.; Bodei, S.; Zani, D.; Simeone, C.; Cunico, S.C.; Missale, C.; Spano, P.; Sigala, S. Nerve growth factor signaling in prostate health and disease. Growth Factors 2010, 28, 191–201. [Google Scholar]

- Montano, X.; Djamgoz, M.B. Epidermal growth factor, neurotrophins and the metastatic cascade in prostate cancer. FEBS Lett. 2004, 571, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Descamps, S.; Lebourhis, X.; Delehedde, M.; Boilly, B.; Hondermarck, H. Nerve growth factor is mitogenic for cancerous but not normal human breast epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1998, 273, 16659–16662. [Google Scholar]

- Descamps, S.; Pawlowski, V.; Revillion, F.; Hornez, L.; Hebbar, M.; Boilly, B.; Hondermarck, H.; Peyrat, J.P. Expression of nerve growth factor receptors and their prognostic value in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 4337–4340. [Google Scholar]

- Le Bourhis, X.; Romon, R.; Hondermarck, H. Role of endothelial progenitor cells in breast cancer angiogenesis: From fundamental research to clinical ramifications. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010, 120, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Romon, R.; Adriaenssens, E.; Lagadec, C.; Germain, E.; Hondermarck, H.; Le Bourhis, X. Nerve growth factor promotes breast cancer angiogenesis by activating multiple pathways. Mol. Cancer 2010, 9, 157. [Google Scholar]

- Com, E.; Lagadec, C.; Page, A.; El Yazidi-Belkoura, I.; Slomianny, C.; Spencer, A.; Hammache, D.; Rudkin, B.B.; Hondermarck, H. Nerve growth factor receptor TrkA signaling in breast cancer cells involves Ku70 to prevent apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2007, 6, 1842–1854. [Google Scholar]

- El Yazidi-Belkoura, I.; Adriaenssens, E.; Dolle, L.; Descamps, S.; Hondermarck, H. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated death domain protein is involved in the neurotrophin receptor- mediated antiapoptotic activity of nerve growth factor in breast cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 16952–16956. [Google Scholar]

- Naderi, A.; Teschendorff, A.E.; Beigel, J.; Cariati, M.; Ellis, I.O.; Brenton, J.D.; Caldas, C. BEX2 is overexpressed in a subset of primary breast cancers and mediates nerve growth factor/nuclear factor-kappaB inhibition of apoptosis in breast cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 6725–6736. [Google Scholar]

- Naderi, A.; Liu, J.; Bennett, I.C. BEX2 regulates mitochondrial apoptosis and G1 cell cycle in breast cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2010, 126, 1596–1610. [Google Scholar]

- Naderi, A.; Liu, J.; Hughes-Davies, L. BEX2 has a functional interplay with c-jun/JNK and p65/RelA in breast cancer. Mol. Cancer 2010, 9, 111. [Google Scholar]

- Brocker, E.B.; Magiera, H.; Herlyn, M. Nerve growth and expression of receptors for nerve growth factor in tumors of melanocyte origin. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1991, 96, 662–665. [Google Scholar]

- Lazar-Molnar, E.; Hegyesi, H.; Toth, S.; Falus, A. Autocrine and paracrine regulation by cytokines and growth factors in melanoma. Cytokine 2000, 12, 547–554. [Google Scholar]

- Truzzi, F.; Marconi, A.; Lotti, R.; Dallaglio, K.; French, L.E.; Hempstead, B.L.; Pincelli, C. Neurotrophins and their receptors stimulate melanoma cell proliferation and migration. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2008, 128, 2031–2040. [Google Scholar]

- Torrisani, J.; Buscail, L. Molecular pathways of pancreatic carcinogenesis. Ann. Pathol. 2002, 22, 349–355. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; Kleeff, J.; Kayed, H.; Wang, L.; Korc, M.; Buchler, M.W.; Friess, H. Nerve growth factor and enhancement of proliferation, invasion, and tumorigenicity of pancreatic cancer cells. Mol. Carcinog. 2002, 35, 138–147. [Google Scholar]

- Greco, A.; Miranda, C.; Pierotti, M.A. Rearrangements of NTRK1 gene in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2010, 321, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Pierotti, M.A.; Vigneri, P.; Bongarzone, I. Rearrangements of Ret and NTRK1 tyrosine kinase receptors in papillary thyroid carcinomas. Recent Results Cancer Res. 1998, 154, 237–247. [Google Scholar]

- Khwaja, F.; Tabassum, A.; Allen, J.; Djakiew, D. The p75(NTR) tumor suppressor induces cell cycle arrest facilitating caspase mediated apoptosis in prostate tumor cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 341, 1184–1192. [Google Scholar]

- Krygier, S.; Djakiew, D. Neurotrophin receptor p75(NTR) suppresses growth and nerve growth factor-mediated metastasis of human prostate cancer cells. Int. J. Cancer 2002, 98, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Krygier, S.; Djakiew, D. Molecular characterization of the loss of p75(NTR) expression in human prostate tumor cells. Mol. Carcinog. 2001, 31, 46–55. [Google Scholar]

- Pflug, B.R.; Onoda, M.; Lynch, J.H.; Djakiew, D. Reduced expression of the low affinity nerve growth factor receptor in benign and malignant human prostate tissue and loss of expression in four human metastatic prostate tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 1992, 52, 5403–5406. [Google Scholar]

- Rende, M.; Rambotti, M.G.; Stabile, A.M.; Pistilli, A.; Montagnoli, C.; Chiarelli, M.T.; Mearini, E. Novel localization of low affinity NGF receptor (p75) in the stroma of prostate cancer and possible implication in neoplastic invasion: An immunohistochemical and ultracytochemical study. Prostate 2010, 70, 555–561. [Google Scholar]

- Brodeur, G.M.; Minturn, J.E.; Ho, R.; Simpson, A.M.; Iyer, R.; Varela, C.R.; Light, J.E.; Kolla, V.; Evans, A.E. Trk receptor expression and inhibition in neuroblastomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 3244–3250. [Google Scholar]

- Harel, L.; Costa, B.; Fainzilber, M. On the death Trk. Dev. Neurobiol. 2010, 70, 298–303. [Google Scholar]

- Kuner, P.; Hertel, C. NGF induces apoptosis in a human neuroblastoma cell line expressing the neurotrophin receptor p75NTR. J. Neurosci. Res. 1998, 54, 465–474. [Google Scholar]

- Katsetos, C.D.; Del Valle, L.; Legido, A.; de Chadarevian, J.P.; Perentes, E.; Mork, S.J. On the neuronal/neuroblastic nature of medulloblastomas: A tribute to Pio del Rio Hortega and Moises Polak. Acta Neuropathol. 2003, 105, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Jemal, A.; Siegel, R.; Xu, J.; Ward, E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2010. caac.20073. [Google Scholar]

- Adriaenssens, E.; Vanhecke, E.; Saule, P.; Mougel, A.; Page, A.; Romon, R.; Nurcombe, V.; Le Bourhis, X.; Hondermarck, H. Nerve growth factor is a potential therapeutic target in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 346–351. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, B.; Reich, R.; Lazarovici, P.; Ann Florenes, V.; Nielsen, S.; Nesland, J.M. Altered expression and activation of the nerve growth factor receptors TrkA and p75 provide the first evidence of tumor progression to effusion in breast carcinoma. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2004, 83, 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Celis, J.E.; Moreira, J.M.; Cabezon, T.; Gromov, P.; Friis, E.; Rank, F.; Gromova, I. Identification of extracellular and intracellular signaling components of the mammary adipose tissue and its interstitial fluid in high risk breast cancer patients: Toward dissecting the molecular circuitry of epithelial-adipocyte stromal cell interactions. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2005, 4, 492–522. [Google Scholar]

- Slamon, D.J.; Clark, G.M.; Wong, S.G.; Levin, W.J.; Ullrich, A.; McGuire, W.L. Human breast cancer: Correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/neu oncogene. Science 1987, 235, 177–182. [Google Scholar]

- Dolle, L.; El Yazidi-Belkoura, I.; Adriaenssens, E.; Nurcombe, V.; Hondermarck, H. Nerve growth factor overexpression and autocrine loop in breast cancer cells. Oncogene 2003, 22, 5592–5601. [Google Scholar]

- Chiarenza, A.; Lazarovici, P.; Lempereur, L.; Cantarella, G.; Bianchi, A.; Bernardini, R. Tamoxifen inhibits nerve growth factor-induced proliferation of the human breast cancerous cell line MCF-7. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 3002–3008. [Google Scholar]

- Muppidi, J.R.; Tschopp, J.; Siegel, R.M. Life and death decisions: Secondary complexes and lipid rafts in TNF receptor family signal transduction. Immunity 2004, 21, 461–465. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.; Bidere, N.; Staudt, D.; Cubre, A.; Orenstein, J.; Chan, F.K.; Lenardo, M. Competitive control of independent programs of tumor necrosis factor receptor-induced cell death by TRADD and RIP1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006, 26, 3505–3513. [Google Scholar]

- Khursigara, G.; Bertin, J.; Yano, H.; Moffett, H.; DiStefano, P.S.; Chao, M.V. A prosurvival function for the p75 receptor death domain mediated via the caspase recruitment domain receptor-interacting protein 2. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 5854–5863. [Google Scholar]

- Zampieri, N.; Chao, M.V. Mechanisms of neurotrophin receptor signalling. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2006, 34, 607–611. [Google Scholar]

- Khursigara, G.; Orlinick, J.R.; Chao, M.V. Association of the p75 neurotrophin receptor with TRAF6. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 2597–2600. [Google Scholar]

- Kanning, K.C.; Hudson, M.; Amieux, P.S.; Wiley, J.C.; Bothwell, M.; Schecterson, L.C. Proteolytic processing of the p75 neurotrophin receptor and two homologs generates C-terminal fragments with signaling capability. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 5425–5436. [Google Scholar]

- Vilar, M.; Murillo-Carretero, M.; Mira, H.; Magnusson, K.; Besset, V.; Ibanez, C.F. Bex1, a novel interactor of the p75 neurotrophin receptor, links neurotrophin signaling to the cell cycle. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 1219–1230. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, K.; Su, Y.; Pang, L.; Lu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, S.; Mao, J.; Zhu, Y. Inhibition of apoptosis by downregulation of hBex1, a novel mechanism, contributes to the chemoresistance of Bcr/Abl+ leukemic cells. Carcinogenesis 2009, 30, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick, D.G.; Burke, H.B.; Djakiew, D.; Euling, S.; Ho, S.M.; Landolph, J.; Morrison, H.; Sonawane, B.; Shifflett, T.; Waters, D.J.; Timms, B. Human prostate cancer risk factors. Cancer 2004, 101, 2371–2490. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, R.A.; Watson, A.Y.; Rhodes, J.A. Biological sources of nerve growth factor. Appl. Neurophysiol. 1984, 47, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, A.A.; Timms, B.G.; Barton, L.; Cunha, G.R.; Grace, O.C. The role of smooth muscle in regulating prostatic induction. Development 2002, 129, 1905–1912. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, C.W.; Lynch, J.H.; Djakiew, D. Distribution of nerve growth factor-like protein and nerve growth factor receptor in human benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostatic adenocarcinoma. J. Urol. 1992, 147, 1444–1447. [Google Scholar]

- Djakiew, D.; Pflug, B.R.; Delsite, R.; Onoda, M.; Lynch, J.H.; Arand, G.; Thompson, E.W. Chemotaxis and chemokinesis of human prostate tumor cell lines in response to human prostate stromal cell secretory proteins containing a nerve growth factor-like protein. Cancer Res. 1993, 53, 1416–1420. [Google Scholar]

- Delsite, R.; Djakiew, D. Characterization of nerve growth factor precursor protein expression by human prostate stromal cells: A role in selective neurotrophin stimulation of prostate epithelial cell growth. Prostate 1999, 41, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Dalal, R.; Djakiew, D. Molecular characterization of neurotrophin expression and the corresponding tropomyosin receptor kinases (trks) in epithelial and stromal cells of the human prostate. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 1997, 134, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Djakiew, D. Dysregulated expression of growth factors and their receptors in the development of prostate cancer. Prostate 2000, 42, 150–160. [Google Scholar]

- Walch, E.T.; Marchetti, D. Role of neurotrophins and neurotrophins receptors in the in vitro invasion and heparanase production of human prostate cancer cells. Clin. Exp.Metastasis 1999, 17, 307–314. [Google Scholar]

- Geldof, A.A.; De Kleijn, M.A.; Rao, B.R.; Newling, D.W. Nerve growth factor stimulates in vitro invasive capacity of DU145 human prostatic cancer cells. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 1997, 123, 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Sortino, M.A.; Condorelli, F.; Vancheri, C.; Chiarenza, A.; Bernardini, R.; Consoli, U.; Canonico, P.L. Mitogenic effect of nerve growth factor (NGF) in LNCaP prostate adenocarcinoma cells: Role of the high- and low-affinity NGF receptors. Mol. Endocrinol. 2000, 14, 124–136. [Google Scholar]

- Krygier, S.; Djakiew, D. The neurotrophin receptor p75NTR is a tumor suppressor in human prostate cancer. Anticancer Res. 2001, 21, 3749–3755. [Google Scholar]

- Delsite, R.; Djakiew, D. Anti-proliferative effect of the kinase inhibitor K252a on human prostatic carcinoma cell lines. J. Androl. 1996, 17, 481–490. [Google Scholar]

- Dionne, C.A.; Camoratto, A.M.; Jani, J.P.; Emerson, E.; Neff, N.; Vaught, J.L.; Murakata, C.; Djakiew, D.; Lamb, J.; Bova, S.; George, D.; Isaacs, J.T. Cell cycle-independent death of prostate adenocarcinoma is induced by the trk tyrosine kinase inhibitor CEP-751 (KT6587). Clin. Cancer Res. 1998, 4, 1887–1898. [Google Scholar]

- Pflug, B.; Djakiew, D. Expression of p75NTR in a human prostate epithelial tumor cell line reduces nerve growth factor-induced cell growth by activation of programmed cell death. Mol. Carcinog. 1998, 23, 106–114. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, J.; Khwaja, F.; Byers, S.; Djakiew, D. The p75NTR mediates a bifurcated signal transduction cascade through the NF kappa B and JNK pathways to inhibit cell survival. Exp. Cell. Res. 2005, 304, 69–80. [Google Scholar]

- Troy, C.M.; Friedman, J.E.; Friedman, W.J. Mechanisms of p75-mediated death of hippocampal neurons. Role of caspases. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 34295–34302. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Bauer, J.H.; Li, Y.; Shao, Z.; Zetoune, F.S.; Cattaneo, E.; Vincenz, C. Characterization of a p75(NTR) apoptotic signaling pathway using a novel cellular model. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 33812–33820. [Google Scholar]

- Fabian, M.R.; Sonenberg, N.; Filipowicz, W. Regulation of mRNA translation and stability by microRNAs. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2010, 79, 351–379. [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder, B.; Seshadri, V.; Fox, P.L. Translational control by the 3′-UTR: The ends specify the means. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2003, 28, 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, C.; Clementi, M.; Benitez, D.; Contreras, H.; Huidobro, C.; Castellon, E. Effect of GnRH analogs on the expression of TrkA and p75 neurotrophin receptors in primary cell cultures from human prostate adenocarcinoma. Prostate 2005, 65, 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, L.W.; Haykowsky, M.; Peddle, C.J.; Joy, A.A.; Pituskin, E.N.; Tkachuk, L.M.; Courneya, K.S.; Slamon, D.J.; Mackey, J.R. Cardiovascular risk profile of patients with HER2/neu-positive breast cancer treated with anthracycline-taxane-containing adjuvant chemotherapy and/or trastuzumab. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2007, 16, 1026–1031. [Google Scholar]

- Miknyoczki, S.J.; Chang, H.; Klein-Szanto, A.; Dionne, C.A.; Ruggeri, B.A. The Trk tyrosine kinase inhibitor CEP-701 (KT-5555) exhibits significant antitumor efficacy in preclinical xenograft models of human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 1999, 5, 2205–2212. [Google Scholar]

- Festuccia, C.; Muzi, P.; Gravina, G.L.; Millimaggi, D.; Speca, S.; Dolo, V.; Ricevuto, E.; Vicentini, C.; Bologna, M. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor CEP-701 blocks the NTRK1/NGF receptor and limits the invasive capability of prostate cancer cells in vitro. Int. J. Oncol. 2007, 30, 193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Weeraratna, A.T.; Dalrymple, S.L.; Lamb, J.C.; Denmeade, S.R.; Miknyoczki, S.; Dionne, C.A.; Isaacs, J.T. Pan-trk inhibition decreases metastasis and enhances host survival in experimental models as a result of its selective induction of apoptosis of prostate cancer cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2001, 7, 2237–2245. [Google Scholar]

- George, D.J.; Dionne, C.A.; Jani, J.; Angeles, T.; Murakata, C.; Lamb, J.; Isaacs, J.T. Sustained in vivo regression of Dunning H rat prostate cancers treated with combinations of androgen ablation and Trk tyrosine kinase inhibitors, CEP-751 (KT-6587) or CEP-701 (KTt-5555). Cancer Res. 1999, 59, 2395–2401. [Google Scholar]

- Longo, F.M.; Massa, S.M. Small molecule modulation of p75 neurotrophin receptor functions. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2008, 7, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita, T.; Tohyama, M. The p75 receptor acts as a displacement factor that releases rho from Rho-GDI. Nature Neurosci. 2003, 6, 461–467. [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun, A.; Lawrance, G.M.; Shamovsky, I.L.; Riopelle, R.J.; Ross, G.M. Differential activity of the nerve growth factor (NGF) antagonist PD90780 [7-(benzolylamino)-4,9-dihydro-4-methyl-9-oxo-pyrazolo[5,1-b]quinazoline-2 -carboxylic acid] suggests altered NGF-p75NTR interactions in the presence of TrkA. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004, 310, 505–511. [Google Scholar]

- Niederhauser, O.; Mangold, M.; Schubenel, R.; Kusznir, E.A.; Schmidt, D.; Hertel, C. NGF ligand alters NGFsignaling via p75(NTR) and TrkA. J. Neurosci. Res. 2000, 61, 263–272. [Google Scholar]

- Warrington, R.J.; Lewis, K.E. Natural antibodies against nerve growth factor inhibit in vitro prostate cancer cell metastasis. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2010, 60, 187–195. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, N.E.; Schnitzer, T.J.; Birbara, C.A.; Mokhtarani, M.; Shelton, D.L.; Smith, M.D.; Brown, M.T. Tanezumab for the treatment of pain from osteoarthritis of the knee. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 1521–1531. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, J.N. Nerve growth factor and pain. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 1572–1573. [Google Scholar]

© 2011 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Molloy, N.H.; Read, D.E.; Gorman, A.M. Nerve Growth Factor in Cancer Cell Death and Survival. Cancers 2011, 3, 510-530. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers3010510

Molloy NH, Read DE, Gorman AM. Nerve Growth Factor in Cancer Cell Death and Survival. Cancers. 2011; 3(1):510-530. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers3010510

Chicago/Turabian StyleMolloy, Niamh H., Danielle E. Read, and Adrienne M. Gorman. 2011. "Nerve Growth Factor in Cancer Cell Death and Survival" Cancers 3, no. 1: 510-530. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers3010510