Conotoxin Interactions with α9α10-nAChRs: Is the α9α10-Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor an Important Therapeutic Target for Pain Management?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

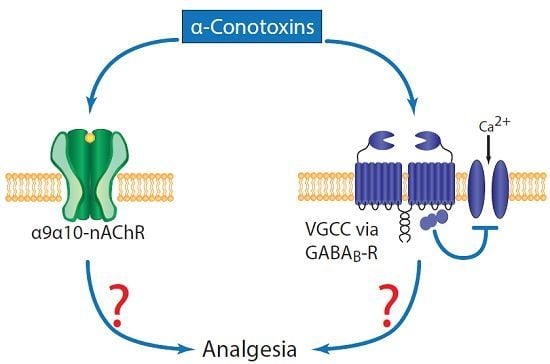

2. nAChRs Involved in Pain

3. α-Conotoxins and Pain

| Vc1.1

Conus victoriae |  | α9α10 | N-type VGCC via GABABR | Yes |

| RgIA

Conus Regius |  | α9α10 | N-type VGCC via GABABR | Yes |

| PeIA

Conus pergrandis |  | α9α10, α3β2 | N-type VGCC via GABABR | Not tested |

| AuIB

Conus aulicus |  | α3β4 | N-type VGCC via GABABR | Yes |

4. Evidence for α9α10-nAChR-Inhibition for Analgesia

4.1. Analgesic α-Conotoxins

4.2. Functional Recovery

4.3. Side Effects

4.4. Non-Peptide, Small-Molecule α9α10-nAChR Inhibitors

5. Evidence against α9α10-nAChR-Inhibition for Analgesia

5.1. Vc1.1 Analogue and Native Peptide

5.2. α9-nAChR KO Phenotype

| Compound Name | Analgesic? | Side Effects? | Functional Recovery? | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nerve Injury (PNL or CCI) | Formalin | Vincristine | ||||||

| Von Frey | R-S | Incap. | ||||||

| Vc1.1 | Yes | Yes | - | - | - | No | Yes | [38,50,56,57,58,59,60] |

| RgIA | Yes | Yes | Yes | - | - | N/R | - | [38,55] |

| vc1a | No | - | - | - | - | N/R | Yes | [56,60] |

| [P6O]Vc1.1 | No | - | - | - | - | N/R | - | [56] |

| cVc1.1 | Yes | - | - | - | - | N/R | - | [40] |

| ZZ-204G | - | Yes | - | Yes | - | Yes | - | [64] |

| ZZ1-61c | - | - | - | - | Yes | No | - | [65] |

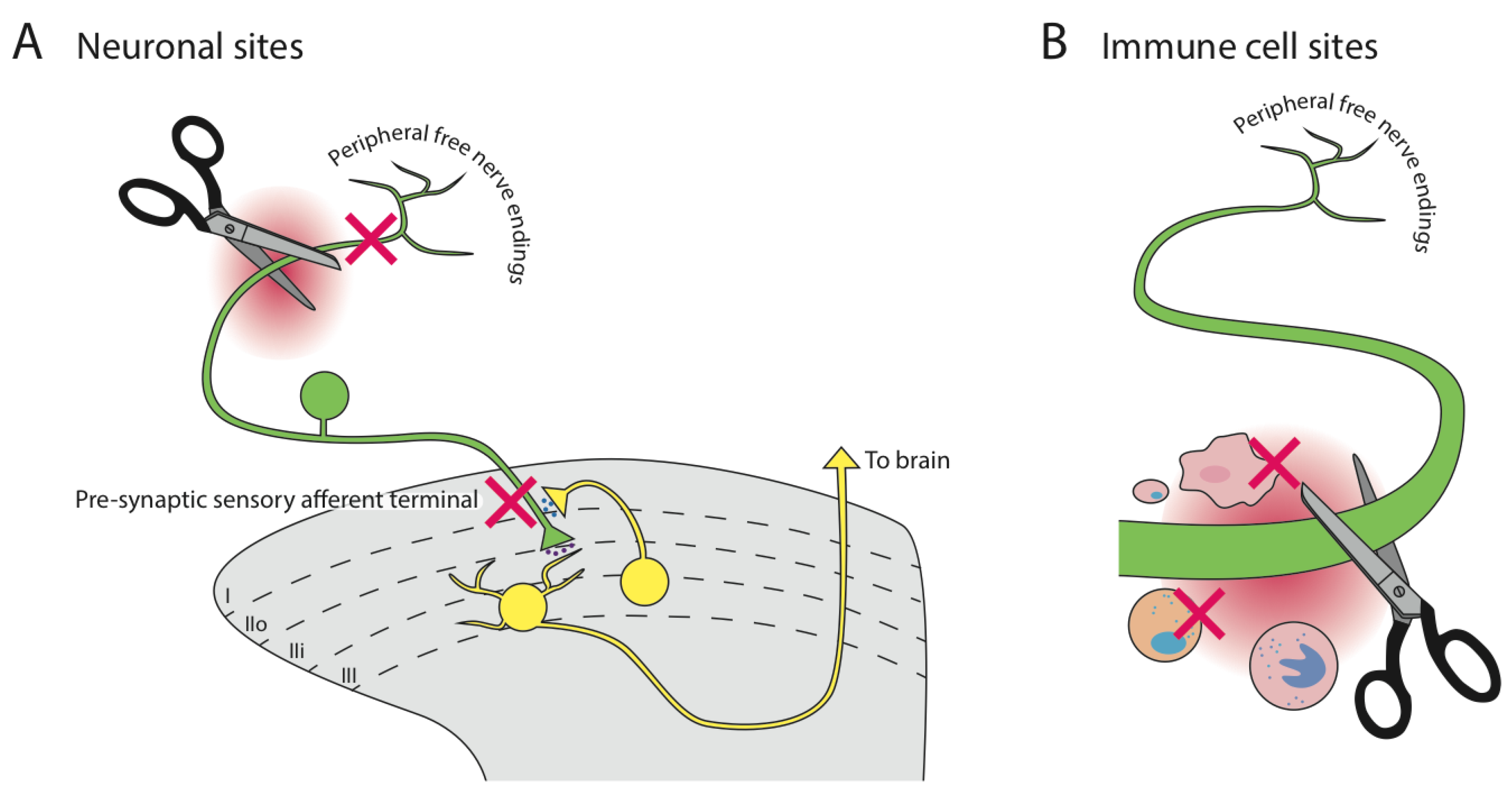

6. The Site(s) of Action of α9α10-nAChR Inhibiting Analgesics is Unknown

6.1. Immune Cells

6.2. Neuronal Cells

6.3. Acetylcholine Source

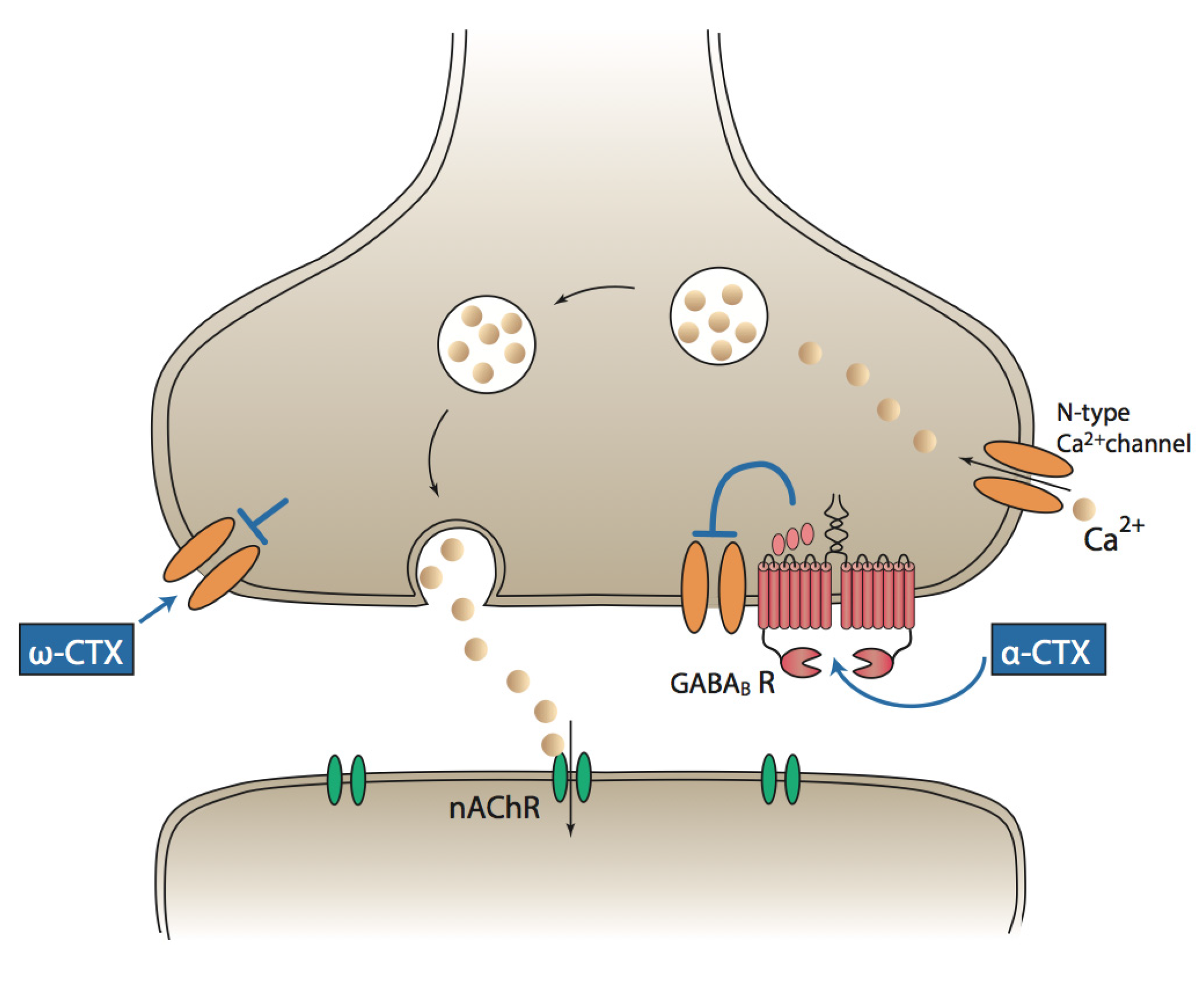

7. An Alternative Mechanism of α-Conotoxin Analgesia Is Known

8. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Merskeu, H.; Bogduk, N. Part III: Pain terms, a current list with definitions and notes on usage. In Classification of Chronic Pain, 2nd ed.; IASP Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 1994; pp. 209–214. [Google Scholar]

- Gureje, O.; Simon, G.E.; von Korff, M. A cross-national study of the course of persistent pain in primary care. Pain 2001, 92, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskin, D.J.; Richard, P. The economic costs of pain in the United States. J. Pain 2012, 13, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddall, P.J.; Cousins, M.J. Persistent pain as a disease entity: Implications for clinical management. Anesth. Analg. 2004, 99, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, I.; Bushnell, M.C. How neuroimaging studies have challenged us to rethink: Is chronic pain a disease? J. Pain 2009, 10, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, W.A.; Barkin, R.L. Dilemmas in chronic/persistent pain management. Am. J. Ther. 2008, 15, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levendoglu, F.; Ogun, C.O.; Ozerbil, O.; Ogun, T.C.; Ugurlu, H. Gabapentin is a first line drug for the treatment of neuropathic pain in spinal cord injury. Spine 2004, 29, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiffen, P.J.; Derry, S.; Moore, R.A.; Aldington, D.; Cole, P.; Rice, A.S.C.; Lunn, M.P.T.; Hamunen, K.; Haanpaa, M.; Kalso, E.A. Antiepileptic drugs for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia: An overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 11, CD010567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroeder, C.I.; Lewis, R.J. ω-conotoxins GVIA, MVIIA and CVID: SAR and clinical potential. Mar. Drugs 2006, 4, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, O.; McArthur, J.R.; Adams, D.J. Conotoxins targeting neuronal voltage-gated sodium channel subtypes: Potential analgesics? Toxins 2012, 4, 1236–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bautista, D.M.; Siemens, J.; Glazer, J.M.; Tsuruda, P.R.; Basbaum, A.I.; Stucky, C.L.; Jordt, S.E.; Julius, D. The menthol receptor TRPM8 is the principal detector of environmental cold. Nature 2007, 448, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caterina, M.J.; Schumacher, M.A.; Tominaga, M.; Rosen, T.A.; Levine, J.D.; Julius, D. The capsaicin receptor: A heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature 1997, 389, 816–824. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lapointe, T.K.; Altier, C. The role of TRPA1 in visceral inflammation and pain. Channels 2011, 5, 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, R.J.; Dutertre, S.; Vetter, I.; Christie, M.J. Conus venom peptide pharmacology. Pharmacol. Rev. 2012, 64, 259–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, A.; Denome, S.; Jiang, Y.Q.; Marangoudakis, S.; Lipscombe, D. Opioid inhibition of N-type Ca2+ channels and spinal analgesia couple to alternative splicing. Nat. Neurosci. 2010, 13, 1249–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altier, C.; Dale, C.S.; Kisilevsky, A.E.; Chapman, K.; Castiglioni, A.J.; Matthews, E.A.; Evans, R.M.; Dickenson, A.H.; Lipscombe, D.; Vergnolle, N.; et al. Differential role of N-type calcium channel splice isoforms in pain. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 6363–6373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vetter, I.; Lewis, R.J. Therapeutic potential of cone snail venom peptides (conopeptides). Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2012, 12, 1546–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millar, N.S.; Gotti, C. Diversity of vertebrate nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neuropharmacology 2009, 56, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, R.J.; Nielsen, K.J.; Craik, D.J.; Loughnan, M.L.; Adams, D.A.; Sharpe, I.A.; Luchian, T.; Adams, D.J.; Bond, T.; Thomas, L.; et al. Novel ω-conotoxins from Conus catus discriminate among neuronal calcium channel subtypes. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 35335–35344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.M.; Green, B.R.; Catlin, P.; Fiedler, B.; Azam, L.; Chadwick, A.; Terlau, H.; McArthur, J.R.; French, R.J.; Gulyas, J.; et al. Structure/Function characterization of μ-conotoxin KIIIA, an analgesic, nearly irreversible blocker of mammalian neuronal sodium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 30699–30706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotti, C.; Clementi, F. Neuronal nicotinic receptors: From structure to pathology. Prog. Neurobiol. 2004, 74, 363–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgoyhen, A.B.; Johnson, D.S.; Boulter, J.; Vetter, D.E.; Heinemann, S. α9: An acetylcholine receptor with novel pharmacological properties expressed in rat cochlear hair-cells. Cell 1994, 79, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotti, C.; Hanke, W.; Maury, K.; Moretti, M.; Ballivet, M.; Clementi, F.; Bertrand, D. Pharmacology and biophysical properties of α7 and α7-α8 α-bungarotoxin receptor subtypes immunopurified from the chick optic lobe. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1994, 6, 1281–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cepeda-Benito, A.; Reynoso, J.; McDaniel, E.H. Associative tolerance to nicotine analgesia in the rat: Tail-flick and hot-plate tests. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1998, 6, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umana, I.C.; Daniele, C.A.; McGehee, D.S. Neuronal nicotinic receptors as analgesic targets: It’s a winding road. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2013, 86, 1208–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, B.X.; Hierl, M.; Clarkin, K.; Juan, T.; Nguyen, H.; van der Valk, M.; Deng, H.; Guo, W.H.; Lehto, S.G.; Matson, D.; et al. Pharmacological effects of nonselective and subtype-selective nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonists in animal models of persistent pain. Pain 2010, 149, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, P.M.; Burgstahler, R.; Sippel, W.; Irnich, D.; Schlotter-Weigel, B.; Grafe, P. Characterization of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the membrane of unmyelinated human C-fiber axons by in vitro studies. J. Neurophysiol. 2003, 90, 3295–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, D.; Nakatsuka, T.; Papke, R.; Gu, J. Modulation of inhibitory synaptic activity by a non-α4β2, non-α7 subtype of nicotinic receptors in the substantia gelatinosa of adult rat spinal cord. Pain 2003, 101, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincler, M.; Eisenach, J. Plasticity of spinal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors following spinal nerve ligation. Neurosci. Res. 2004, 48, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arneric, S.P.; Holladay, M.; Williams, M. Neuronal nicotinic receptors: A perspective on two decades of drug discovery research. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2007, 74, 1092–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurst, R.; Rollema, H.; Bertrand, D. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: From basic science to therapeutics. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 137, 22–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivera, B.M.; Quik, M.; Vincler, M.; McIntosh, J.M. Subtype-selective conopeptides targeted to nicotinic receptors—Concerted discovery and biomedical applications. Channels 2008, 2, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias, H.R.; Blanton, M.P. α-Conotoxins. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2000, 32, 1017–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, A.H.; Vetter, I.; Dutertre, S.; Abraham, N.; Emidio, N.B.; Inserra, M.; Murali, S.S.; Christie, M.J.; Alewood, P.F.; Lewis, R.J. MrIC, a novel α-conotoxin agonist in the presence of PNU at endogenous α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutton, J.L.; Craik, D.J. α-Conotoxins: Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonists as pharmacological tools and potential drug leads. Curr. Med. Chem. 2001, 8, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebbe, E.K.M.; Peigneur, S.; Wijesekara, I.; Tytgat, J. Conotoxins targeting nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: An overview. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 2970–3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, R.J.; Fischer, H.; Nevin, S.T.; Adams, D.J.; Craik, D.J. The synthesis, structural characterization, and receptor specificity of the α-conotoxin Vc1.1. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 23254–23263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincler, M.; Wittenauer, S.; Parker, R.; Ellison, M.; Olivera, B.M.; McIntosh, J.M. Molecular mechanism for analgesia involving specific antagonism of α9α10 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 17880–17884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellison, M.; Haberlandt, C.; Gomez-Casati, M.E.; Watkins, M.; Elgoyhen, A.B.; McIntosh, J.M.; Olivera, B.M. α-RgIA: A novel conotoxin that specifically and potently blocks the α9α10 nAChR. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 1511–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, R.J.; Jensen, J.; Nevin, S.T.; Callaghan, B.P.; Adams, D.J.; Craik, D.J. The engineering of an orally active conotoxin for the treatment of neuropathic pain. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 6545–6548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halai, R.; Caaghan, B.; Daly, N.L.; Clark, R.J.; Adams, D.J.; Craik, D.J. Effects of cyclization on stability, structure, and activity of alpha-Conotoxin RgIA at the alpha 9 alpha 10 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor and GABA(B) receptor. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 6984–6992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Lierop, B.J.; Robinson, S.D.; Kompella, S.N.; Belgi, A.; McArthur, J.R.; Hung, A.; MacRaild, C.A.; Adams, D.J.; Norton, R.S.; Robinson, A.J. Dicarba α-conotoxin Vc1.1 analogues with differential selectivity for nicotinic acetylcholine and GABA(B) receptors. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 1815–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chhabra, S.; Belgi, A.; Bartels, P.; van Lierop, B.J.; Robinson, S.D.; Kompella, S.N.; Hung, A.; Callaghan, B.P.; Adams, D.J.; Robinson, A.J. Dicarba analogues of α-conotoxin RgIA. Structure, stability, and activity at potential pain targets. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 9933–9944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, E.G.; Cassels, B.K.; Zapata-Torres, G. Molecular modeling of the α9α10 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtype. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callaghan, B.; Adams, D.J. Analgesic α-conotoxins Vc1.1 and RgIA inhibit N-type calcium channels in sensory neurons of α9 nicotinic receptor knockout mice. Channels 2010, 4, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haberberger, R.V.; Bernardini, N.; Kress, M.; Hartmann, P.; Lips, K.S.; Kummer, W. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes in nociceptive dorsal root ganglion neurons of the adult rat. Auton. Neurosci. 2004, 113, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lips, K.S.; Pfeil, U.; Kummer, W. Coexpression of α9 and α10 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Neuroscience 2002, 115, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgoyhen, A.B.; Vetter, D.E.; Katz, E.; Rothlin, C.V.; Heinemann, S.F.; Boulter, J. α10: A determinant of nicotinic cholinergic receptor function in mammalian vestibular and cochlear mechanosensory hair cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 3501–3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vetter, D.E.; Liberman, M.C.; Mann, J.; Barhanin, J.; Boulter, J.; Brown, M.C.; Saffiote-Kolman, J.; Heinemann, S.F.; Elgoyhen, A.B. Role of α9 nicotinic ACh receptor subunits in the development and function of cochlear efferent innervation. Neuron 1999, 23, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satkunanathan, N.; Livett, B.; Gayler, K.; Sandall, D.; Down, J.; Khalil, Z. Alpha-conotoxin Vc1.1 alleviates neuropathic pain and accelerates functional recovery of injured neurones. Brain Res. 2005, 1059, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azam, L.; McIntosh, J.M. Molecular basis for the differential sensitivity of rat and human α9α10 nAChRs to α-conotoxin RgIA. J. Neurochem. 2012, 122, 1137–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metabolic discontinues clinical trial programme for neuropathic pain drug, ACV1. Available online: http://www.asx.com.au/asxpdf/20070814/pdf/313yjgpf7jl4lg.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2014).

- McIntosh, J.M.; Absalom, N.; Chebib, M.; Elgoyhen, A.B.; Vincler, M. Alpha9 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and the treatment of pain. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2009, 78, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, D.J.; Callaghan, B.; Berecki, G. Analgesic conotoxins: Block and G protein-coupled receptor modulation of N-type (CaV2.2) calcium channels. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 166, 486–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mannelli, L.D.C.; Cinci, L.; Micheli, L.; Zanardelli, M.; Pacini, A.; McIntosh, M.J.; Ghelardini, C. α-Conotoxin RgIA protects against the development of nerve injury-induced chronic pain and prevents both neuronal and glial derangement. Pain 2014, 155, 1986–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nevin, S.T.; Clark, R.J.; Klimis, H.; Christie, M.J.; Craik, D.J.; Adams, D.J. Are α9α10 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors a pain target for α-conotoxins? Mol. Pharmacol. 2007, 72, 1406–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klimis, H.; Adams, D.J.; Callaghan, B.; Nevin, S.; Alewood, P.F.; Vaughan, C.W.; Mozar, C.A.; Christie, M.J. A novel mechanism of inhibition of high-voltage activated calcium channels by α-conotoxins contributes to relief of nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain. Pain 2011, 152, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napier, I.A.; Klimis, H.; Rycroft, B.K.; Jin, A.H.; Alewood, P.F.; Motin, L.; Adams, D.J.; Christie, M.J. Intrathecal α-conotoxins Vc1.1, AuIB and MII acting on distinct nicotinic receptor subtypes reverse signs of neuropathic pain. Neuropharmacology 2012, 62, 2202–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, S.; Christie, M.J. α9-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors contribute to the maintenance of chronic mechanical hyperalgesia, but not thermal or mechanical allodynia. Mol. Pain 2014, 10, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livett, B.; Khalil, Z.; Gayler, K.; Down, J. Alpha Conotoxin Peptides with Analgesic Properties. Patent number WO 02/079236 A1; filed 28 March 2002 and issued 10 October 2002,

- Sandall, D.W.; Satkunanathan, N.; Keays, D.A.; Polidano, M.A.; Liping, X.; Pham, V.; Down, J.G.; Khalil, Z.; Livett, B.G.; Gayler, K.R. A novel α-conotoxin identified by gene sequencing is active in suppressing the vascular response to selective stimulation of sensory nerves in vivo. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 6904–6911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, S.; Christie, M.J.; The University of Sydney, NSW, Australia. Unpublished work. 2015.

- Vincler, M.; McIntosh, J.M. Targeting the α9α10 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor to treat severe pain. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2007, 11, 891–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holtman, J.R.; Dwoskin, L.P.; Dowell, C.; Wala, E.P.; Zhang, Z.F.; Crooks, P.A.; McIntosh, J.M. The novel small molecule α9α10 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist ZZ-204G is analgesic. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 670, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wala, E.P.; Crooks, P.A.; McIntosh, J.M.; Holtman, J.R. Novel small molecule α9α10 nicotinic receptor antagonist prevents and reverses chemotherapy-evoked neuropathic pain in rats. Anesth. Analg. 2012, 115, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawashima, K.; Fujii, T. Expression of non-neuronal acetylcholine in lymphocytes and its contribution to the regulation of immune function. Front. Biosci. 2004, 9, 2063–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinner, I.; Felsner, P.; Falus, A.; Skreiner, E.; Kukulansky, T.; Globerson, A.; Hirokawa, K.; Schauenstein, K. Cholinergic signals to and from the immune-system. Immunol. Lett. 1995, 44, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.Z.; Fujii, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Yamada, S.; Ando, T.; Kazuko, F.; Kawashima, K. Diversity of mRNA expression for muscarinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes and neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits in human mononuclear leukocytes and leukemic cell lines. Neurosci. Lett. 1999, 266, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.S.; Ferris, R.L.; Matthews, T.; Hiel, H.; Lopez-Albaitero, A.; Lustig, L.R. Characterization of the human nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit alpha (α) 9 (CHRNA9) and alpha (α) 10 (CHRNA10) in lymphocytes. Life Sci. 2004, 76, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genzen, J.R.; van Cleve, W.; McGehee, D.S. Dorsal root ganglion neurons express multiple nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes. J. Neurophysiol. 2001, 86, 1773–1782. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dubé, G.R.; Kohlhaas, K.L.; Rueter, L.E.; Surowy, C.S.; Meyer, M.D.; Briggs, C.A. Loss of functional neuronal nicotinic receptors in dorsal root ganglion neurons in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Neurosci. Lett. 2005, 376, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damaj, M.I.; Fei-Yin, M.; Dukat, M.; Glassco, W.; Glennon, R.A.; Martin, B.R. Antinociceptive responses to nicotinic acetylcholine receptor ligands after systemic and intrathecal administration in mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998, 284, 1058–1065. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kong, J.H.; Adelman, J.P.; Fuchs, P.A. Expression of the SK2 calcium-activated potassium channel is required for cholinergic function in mouse cochlear hair cells. J. Physiol. 2008, 586, 5471–5485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, T.; Wang, Y.; Guo, C.K.; Zhang, W.J.; Yu, H.; Zhang, K.; Kong, W.J. Two distinct channels mediated by m2mAChR and α9nAChR co-exist in type II vestibular hair cells of guinea pig. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 8818–8831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halai, R.; Clark, R.J.; Nevin, S.T.; Jensen, J.E.; Adams, D.J.; Craik, D.J. Scanning mutagenesis of α-conotoxin Vc1.1 reveals residues crucial for activity at the α9α10 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 20275–20284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesnage, B.; Gaillard, S.; Godin, A.G.; Rodeau, J.L.; Hammer, M.; von Engelhardt, J.; Wiseman, P.W.; de Koninck, Y.; Schlichter, R.; Cordero-Erausquin, M. Morphological and functional characterization of cholinergic interneurons in the dorsal horn of the mouse spinal cord. J. Comp. Neurol. 2011, 519, 3139–3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, M.; Xie, W.J.; Inoue, M.; Ueda, H. Evidence for the tonic inhibition of spinal pain by nicotinic cholinergic transmission through primary afferents. Mol. Pain 2007, 3, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dussor, G.O.; Jones, D.J.; Hulsebosch, C.E.; Edell, T.A.; Flores, C.M. The effects of chemical or surgical deafferentation on H-3-acetylcholine release from rat spinal cord. Neuroscience 2005, 135, 1269–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grando, S.A.; Kist, D.A.; Qi, M.; Dahl, M.V. Human keratinocytes synthesize, secrete, and degrade acetylcholine. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1993, 101, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawashima, K.; Fujii, T. Basic and clinical aspects of non-neuronal acetylcholine: Overview of non-neuronal cholinergic systems and their biological significance. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2008, 106, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihovilovic, M.; Denning, S.; Mai, Y.; Fisher, C.M.; Whichard, L.P.; Patel, D.D.; Roses, A.D. Thymocytes and cultured thymic epithelial cells express transcripts encoding α-3, α-5, and β-4 subunits of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors—Preferential transcription of the α-3 and β-4 genes by immature CD4+8+ thymocytes and evidence for response to nicotine in thymocytes. In Myasthenia Gravis and Related Diseases: Disorders of the Neuromuscular Junction; Richman, D.P., Ed.; New York Acad Sciences: New York, NY, USA, 1998; Volume 841, pp. 388–392. [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima, K.; Yoshikawa, K.; Fujii, Y.X.; Moriwaki, Y.; Misawa, H. Expression and function of genes encoding cholinergic components in murine immune cells. Life Sci. 2007, 80, 2314–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, B.; Haythornthwaite, A.; Berecki, G.; Clark, R.J.; Craik, D.J.; Adams, D.J. Analgesic α-conotoxins Vc1.1 and Rg1A inhibit N-type calcium channels in rat sensory neurons via GABA(B) receptor activation. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 10943–10951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grishin, A.A.; Cuny, H.; Hung, A.; Clark, R.J.; Brust, A.; Akondi, K.; Alewood, P.F.; Craik, D.J.; Adams, D.J. Identifying key amino acid residues that affect α-conotoxin AuIB inhibition of α3β4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 34428–34442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daly, N.L.; Callaghan, B.; Clark, R.J.; Nevin, S.T.; Adams, D.J.; Craik, D.J. Structure and activity of α-conotoxin PeIA at nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes and GABA(B) receptor-coupled N-type calcium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 10233–10237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, J.M.; Plazas, P.V.; Watkins, M.; Gomez-Casati, M.E.; Olivera, B.M.; Elgoyhen, A.B. A novel α-conotoxin, PeIA, cloned from Conus pergrandis, discriminates between rat α9α10 and α7 nicotinic cholinergic receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 30107–30112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, L.; Bennett, T.; Jung, H.H.; Ryan, A.F. Developmental expression of α9 acetylcholine receptor mRNA in the rat cochlea and vestibular inner ear. J. Comp. Neurol. 1998, 393, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.J.; Berecki, G. Mechanisms of conotoxin inhibition of N-type (Cav2.2) calcium channels. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1828, 1619–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mohammadi, S.A.; Christie, M.J. Conotoxin Interactions with α9α10-nAChRs: Is the α9α10-Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor an Important Therapeutic Target for Pain Management? Toxins 2015, 7, 3916-3932. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins7103916

Mohammadi SA, Christie MJ. Conotoxin Interactions with α9α10-nAChRs: Is the α9α10-Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor an Important Therapeutic Target for Pain Management? Toxins. 2015; 7(10):3916-3932. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins7103916

Chicago/Turabian StyleMohammadi, Sarasa A., and MacDonald J. Christie. 2015. "Conotoxin Interactions with α9α10-nAChRs: Is the α9α10-Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor an Important Therapeutic Target for Pain Management?" Toxins 7, no. 10: 3916-3932. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins7103916