1. Introduction

Numerous epidemiological and clinical trials have suggested that regular nut consumption has a beneficial effect on many health outcomes such as coronary heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, gallstones, weight gain over time, obesity, visceral obesity, metabolic syndrome, cancer and total mortality [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. A number of studies have suggested significant protective effect of nuts against depression, mild cognitive disorders and Alzheimer’s disease [

1]. Nuts, alone or as part of healthy dietary patterns, may exert beneficial effects due to their richness in antioxidants, including vitamins, polyphenols and unsaturated fatty acids, that may be protective against the development of cognitive decline and depression [

8,

9]. Walnuts contain several neuroprotective compounds like vitamin E, folate, melatonin and several polyphenols [

10,

11] (

Table 1). Furthermore, walnuts also contain ω-3 α-linolenic acid (ALA; 18:3

n-3) that can directly interact with the physiology of the brain. ALA is the precursor of Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA; 20:5

n-3) and Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA; 22:6

n-3) [

12]. DHA is an important ω-3 fatty acid (FA) responsible, among others, for membrane stability, neuroplasticity, speed of signal transduction, and modulation of serotonin and dopamine concentrations [

13]. There is growing evidence that the synergy and interaction of all the nutrients and other bioactive components in nuts have beneficial effect on brain and cognition [

12]. Studies regarding the effects of nuts consumption on cognitive functions are scarce. Most of the research on the relationship between nut consumption and cognitive functions has been done using animals or pathological populations [

14,

15]. There are presently no studies that investigated whether nut intake could be differently associated with changes in mood in men and women. Our study is also the only intervention study so far performed on healthy subjects. Thus, we have designed our study to evaluate the effects of walnut consumption on mood in a population of healthy young volunteers. Results suggest that regular walnut consumption in young males could improve mood.

4. Discussion

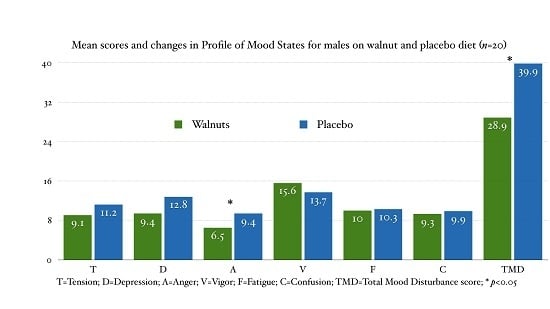

In this double-blind, randomized, placebo controlled, cross-over trial supplementation with walnuts for eight weeks we did not observe any improvement in mood in the combined analysis and in females. However, in young healthy males we have observed a significant, medium effect size improvement of the TMD score.

There are very few studies regarding nut consumption and depression. Pooled meta-analysis, synthesizing results of nine studies (one longitudinal cohort, one case-control and seven cross-sectional) examining the association between adherence to a Mediterranean diet (MD) and depression, showed a 32% reduction in the risk of depression (RR = 0.68, 95% CI 0.54–0.86) in individuals with high dietary adherence to the MD. The protective effect of high adherence to the MD was independent of age, whereas moderate adherence lost its protective properties in older age [

20]. MD is characterized by high intake of vegetables, fruits, cereals, pulses, nuts and seeds; moderate consumption of dairy products, fish, poultry and eggs; generous use of olive oil and moderate intake of wine with meals [

21]. In the PREDIMED trial, a nutritional intervention with the MD supplemented with nuts showed a 40% lower risk of depression in participants with type 2 diabetes (RR = 0.59, 95% CI 0.36–0.98). However, the inverse association with depression was not significant (RR = 0.78, 95% CI 0.55–1.10) in the whole cohort [

22]. However, the evidence for the protective effect of nuts from these studies is only indirect in the setting of a healthy MD.

There are several nutrients in walnuts that could be responsible for the reduced risk of depression and improved mood. Walnuts are different from other tree nuts because of their greater antioxidant capacity, polyphenols and ALA content. Walnuts are an excellent source of ω-3 FA; 28 g of walnuts (recommended daily dose) contains 2.6 g of ALA. ALA found in walnuts is associated with improved endothelial function and inflammation in animal models [

23]. Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFA) and Monounsaturated Fatty Acids (MUFA) content may contribute to the improvement in arterial stiffness [

24]. Still, PUFA and specifically ALA can also directly influence brain physiology including structural changes in brain areas associated with affective experiences [

25]. ALA is the precursor for DHA that can modulate serotonin and dopamine concentration known to influence mood and sleep [

13]. The present, available evidence provides some support that ω-3 PUFA intake is associated with reduced depressive symptoms particularly in females [

26,

27]. There are several factors that could contribute to sex-based differences in ω-3 PUFA intake and mood. DHA levels are higher in women than men due to sex hormones; estrogen increases DHA, while testosterone decreases DHA levels [

28]. Conversion of ALA to DHA is higher in women than men [

29]. But, some studies found no sex-based differences [

30], some found opposite sex effect [

31]. There have also been few studies that examined the effect of ω-3 PUFA supplementation on mood in young healthy populations. Fontani et al. reported that ω-3 PUFA supplementation (2.8 g/day) using POMS increased feelings of vigor and reduced feelings of anger, anxiety, fear, depression and confusion [

32]. But, Antypa et al. found that 2.3 g/day of ω-3 PUFA supplementation only reduced feelings of fatigue in POMS but not depression in POMS or Beck Depression Inventory [

33]. Young reported that ω-3 PUFA algae supplementation for eight weeks resulted in increased overall mood disturbance as measured by POMS and Depression Anxiety Stress Scale [

34]. Vitamin E and polyphenols can modify inflammatory mediators [

35,

36]. This vascular and anti-inflammatory benefit alone could contribute to improving cognitive functions including mood. Walnuts contain relatively high levels of food-based melatonin (3.5 ng/g), which can act as powerful antioxidant, and regulator of biological rhythmicity and sleep [

37]. Sufficient sleep has been associated with better mood [

38]. Lastly, walnuts are also rich source of folate. Folate sufficiency is associated with less cognitive impairment and depression [

39].

However, all these results do have only limited applicability because our study was a whole food study [

40]. We have measured the effects of the consumption of the whole walnut on mood with all the possible synergy and interactions between all the nutrients and compound found there.

This is the first intervention study in humans exclusively measuring the effect of walnut consumption on mood. Both males and females in our study scored around the 50th percentile at baseline, indicating that our population was not depressed. Walnut supplementation was able to improve mood only in males. It is not clear why we didn’t observe any mood changes in females.

The TMD score is computed by summing up the five negative domains and subtracting the vigor score. Male participants, when on the walnut diet, experienced non-significant improvements in: tension (−18.61%), depression (−26.52%), anger (−31.15%), vigor (13.42%) and confusion (−6.35%), with no changes in fatigue. When added up, this led to a significant medium size improvement in the TMD score (−27.49%,

p = 0.043, Cohen’s d = 0.708). Our results are intriguing because small improvements attributable to walnut consumption in healthy, cognitively intact young adults could translate into important outcomes in aging populations [

8]. This sex specific influence of walnuts on mood, we have observed, is far from understood and warrants more research.

There are several limitations to our study. The duration of the study may have been too short. We experienced unusually high drop-out rates because of the H1N1 flu epidemic. This attrition rate reduced the level of statistical power available for our analysis. However, the bias that would result from withdrawal of participants with different moods is likely to be negligible. Participant expectation of treatment effects could have altered the results.

Clinical trials often require multiple outcomes and multiple hypotheses to be tested. Such testing involves comparing treatments using multiple outcome measures (MOMs) with univariate statistical methods [

41]. Some researchers argue that if MOMs are tested, the

p-values should be adjusted upward because of the multiple testing problem [

42]. Applying this conservative approach, results for the TMD score for males would be insignificant because the reference

p value would be 0.05/2 = 0.025 (α divided by the two genders). However, objection to

p-values adjustments is that the significance of each test will be interpreted according to how many outcome measures are considered in the family-wise hypothesis and additionally while reducing type I error we increase the chance of making type II error. Therefore, we have used the following recommended strategy to reach reasonable conclusions [

41]: our study was a randomized double blind controlled trial that followed the CONSORT guidelines; the effect size on the TMD score for males was medium (Cohen’s d = 0.708); the focus of the publication are only the primary outcomes—the TMD scores. It is important that further research be done to replicate our results.