Core Elements for Organizational Sustainability in Global Markets: Korean Public Relations Practitioners’ Perceptions of Their Job Roles

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Job Roles of Public Relations Practitioners

2.2. Job Roles of Public Relations Practitioners in Korea

3. Research Questions

4. Method

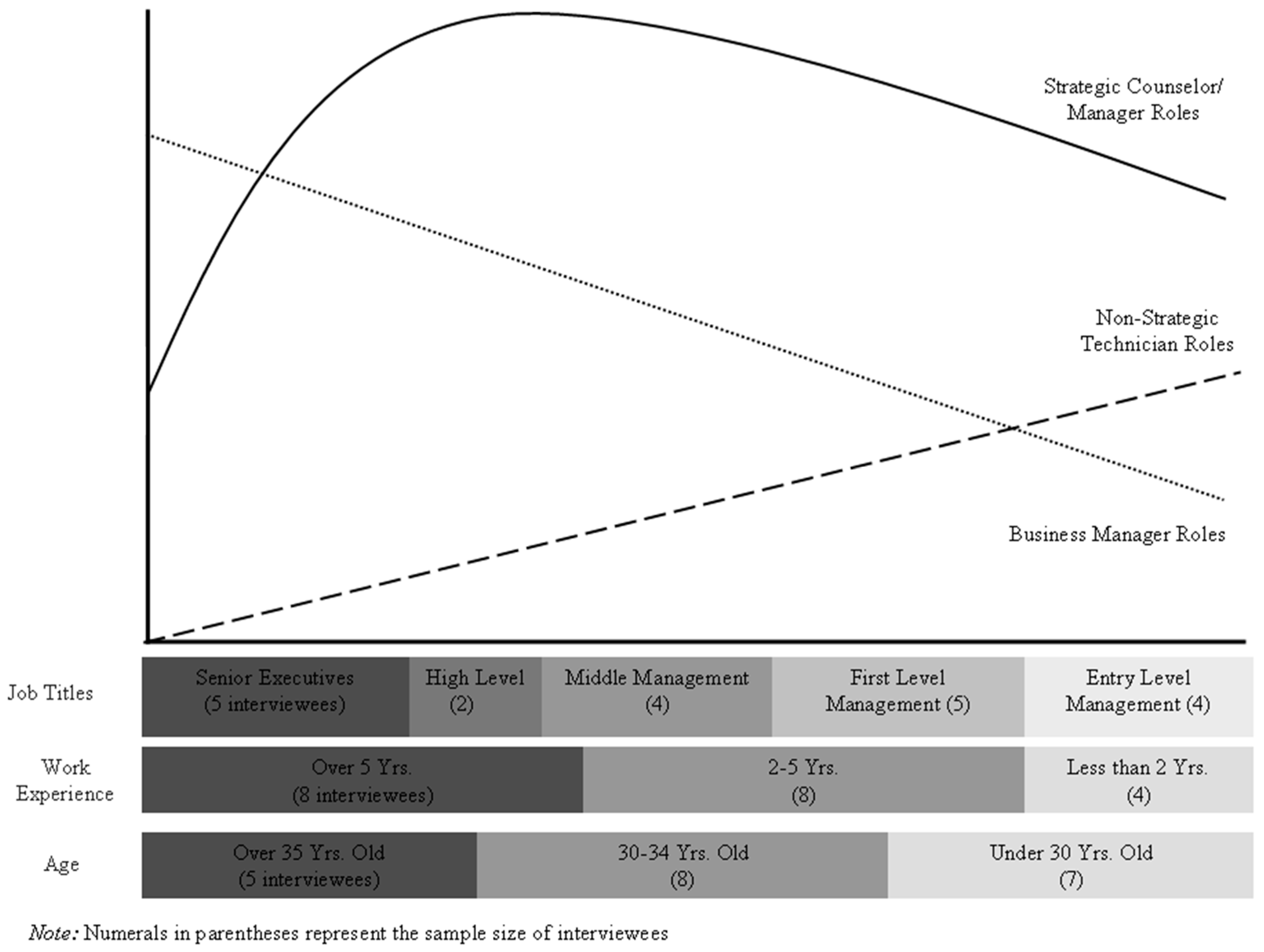

4.1. Participants

4.2. In-Depth Interview Procedures

4.3. Data Analysis Technique

5. Findings

5.1. Korean Public Relations Practitioners’ Perceptions of Their Job Roles

5.1.1. Strategic Counselor/Manager Role

5.1.2. Non-Strategic Technician Role

5.1.3. Business Manager Role for Practitioners’ Own Firms

5.1.4. The Relationship between Practitioners’ Backgrounds and Perceptions of Roles

5.2. Elements Affecting the Job Roles of Korean Practitioners in Global Public Relations Firms

5.2.1. Element 1: Cultural Characteristics

“In particular, providing clients or journalists with entertainment or gifts is a general business practice that is widely accepted in the Korean market. It represents relationship-oriented Korean culture. To build emotional intimate relationship with media or clients, practitioners have to provide entertainment and spend more time with them even after work time. You know Korean culture … it is not an overstatement that Koreans work better or more efficiently if there is an emotional bond. We feel a stronger bond when we find any connection … school ties, geographical ties and so on … with the business partner. For example, once I build a strong relationship with media personnel, the media personnel might help me when I ask for a positive press response regarding my clients’ issues because of Jeong. Of course, I should prepare some interesting news, too. Anyhow, one of the Korean practitioners’ jobs could be building personal relationships with clients or journalists, so to achieve that goal, practitioners serve them.”

“Young practitioners sometimes are limited in their work on government projects because young age is not trusted by old government officials. Young practitioners can’t be assigned responsible jobs but only assistant roles.”

5.2.2. Element 2: Media Environmental Specificity

“Media journalists, especially the journalists who are related to my clients’ industry and who request some information from me are like bosses over my work. Or, I would say they are king! They govern my roles at work. They have big power and we, PR practitioners are affected by them. In general people trust the information media release, so I should listen to media journalists’ every word as well as to their requests. Then I can have good results or achievement in my public relations practice. This is the reality!”

“Korea’s media-centered culture is related to Korea’s unique cultural specificity. Because of media’s special power in Korea, family ties, school ties, and geographical origin ties, which public relations practitioners have, are usually involved with media to control media. And monetary transactions and entertainment for media happen in public relations business.”

5.2.3. Element 3: The General Public’s Perception of Public Relations as Unprofessional

“I myself consider public relations to be a professional field, but most people do not share my opinion. I think the public’s general perception of public relations leads to my clients’ perceptions that public relations practitioners are secondary assistants. Clients’ perceptions affect my job role as a technician … which involves trivial errands, making simple invitation cards, or promoting specific events while having no power to make decisions.”

“Those who don’t know about public relations might perceive that practitioners’ jobs are cool because they think we do something creative. Those who know a little about public relations perceive practitioners’ job as tough because practitioners have to be the legs and arms of their clients. Those clients perceive practitioners as “cheap agent for them” and the media think practitioners are bothersome but necessary beings. This is a practitioners’ reality. The public’s different perceptions decide a practitioners’ work.”

“While a medical doctor, lawyer, or pharmacist, as it is called “professional” by social agreement, public relations practitioners are not perceived that way by the public. Still … many people don’t know what public relations is and what public relations practitioners do. Even my parents don’t know what it is and asked me … like … so what do you do at work? (laugh) … it is a pity.”

“I believe that public relations practitioners debase themselves by providing unlimited services ‘from A to Z’, a characteristic related to the subordinate relationship mentioned previously. Distinct definition of work areas will aid in public relations specialization.”

5.2.4. Element 4: Client Perceptions of Public Relations/Client Relationships

“I think many clients perceive public relations practitioners as their agents, lower class, or subordinate personnel who assist them in their jobs … jobs which they originally thought they could handle alone … but which they no longer can because they don’t have time to do everything. Because they think we are their assistants or secretaries, they ask practitioners to be their arms and legs. As clients make requests, I have no choice but to provide all kinds of services including some which are not part of my main roles. So … I think the relationship with clients and how they perceive public relations or practitioners’ roles determine my roles as a public relations practitioner.”

5.2.5. Element 5: Practitioners’ Own Firms’ Principles and Rules

“My firm has some special rules and policies. My firm’s policies have more influence than anything else has on my role as a practitioner. Sometimes, my clients ask me to do some work for them but I have to reject it based on my firm’s rules … well … for example, sometimes, I have a request from my clients to drink alcohol or enjoy entertainment with media people after my regular work time, but my firm has a rule that requires me to reject this kind of request from clients. Thank God!”

5.2.6. Element 6: Headquarters’ Principles and Rules

“As practitioners, who work in an international PR firm which has headquarters in America, we are obliged to comply with American concepts in determining what kind of job roles are acceptable and what are not. American standards, which are often regarded as global standards, usually do not allow us to follow Korean business practices. Therefore when we tried to establish relationships with stakeholders in the Korean style, it was rejected by our headquarters … so … we have to take much more time to build relationships with Korean stakeholders.”

5.2.7. Element 7: Business Contracts with Clients

“My firm has contracts with government and publicly held organizations. I do my work based on those contracts. It is a three-month project for research and some strategies regarding government issues. So I am like a researcher. … I don’t actually practice what I have suggested for the project. I also don’t do menial technical work because I just do consultant roles or researcher roles.”

5.2.8. Element 8: Practitioners’ Positions/Job Titles

“… my boss’ opinion or decision affects what I have to do. I should have my boss’ confirmation for all my documentation before I send it to my clients. If my boss does not agree with my work, I should change my work … I think it is partly related to Korean culture of hierarchy.”

5.2.9. Element 9: Practitioners’ Academic Qualifications

“My firm assigns practitioners who have master’s degrees in communication or public relations to consulting projects which mainly involve research, not practice. On the other hand, practitioners who have only bachelor’s degrees mostly are not involved with that kind of consulting project. Well, even though they are involved, it is rare or they are not responsible for the project. A consulting project requires professional research ability which can be acquired at the masters’ level in a communication major. Practically, if they don’t have specific research or analysis ability, it is hard to achieve certain roles.”

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

|

References

- Broom, G.M.; Smith, G.D. Testing the practitioner’s impact on clients. Public Relat. Rev. 1979, 5, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSanto, B.; Moss, D. Rediscovering what PR managers do: Rethinking the measurement of managerial behavior in the public relations context. J. Commun. Manag. 2004, 9, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSanto, B.; Moss, D.; Newman, A. Building an understanding of the main elements of management in the communication/public relations context: A study of U.S. practitioners’ practices. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2007, 84, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dozier, D.M. Program evaluation and the roles of practitioners. Public Relat. Rev. 1984, 10, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dozier, D.M.; Broom, G.M. Evolution of the manager role in public relations practice. J. Public Relat. Rev. 1995, 7, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauren, M.M. Public relations practitioner role enactment in issues management. J. Q. 1994, 71, 356–369. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, N.M.; Sha, B.-L.; Dozier, D.M.; Sargent, P. The role of new public relations practitioners as social media experts. Public Relat. Rev. 2015, 41, 411–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neil, M.S.; Moody, M. Who is responsible for what? Examining strategic roles in social media management. Public Relat. Rev. 2015, 41, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellado, C.; Barría, S. Development of professional roles in the practice of public relations in Chile. Public Relat. Rev. 2012, 38, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, T. The description of South African corporate communication practitioners that contribute to organizational performance. Public Relat. Rev. 2014, 40, 193–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, S.L.; Sriramesh, K. Adding value to organizations: An examination of the role of senior public relations practitioners in Singapore. Public Relat. Rev. 2009, 35, 422–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molleda, J.C.; Moreno, A.; Athaydes, A.; Suarez, A.M. Macroencuesta latinoamericana de comunicacion y relaciones publicas. Organicom 2010, 7, 119–141. [Google Scholar]

- Molleda, J.C.; Ferguson, M.A. Public relations roles in Brazil: Hierarchy eclipses gender differences. J. Public Relat. Rev. 2004, 16, 327–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, H.; Akel, D. Elections and earth matters: Public relations in Costa Rica. In International Public Relations. A Comparative Analysis; Culbertson, H.M., Chen, N., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1996; pp. 257–272. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, J.Y. Enhancing organizational survivability in a crisis: Perceived organizational crisis responsibility, stance, and strategy. Sustainability 2015, 7, 11532–11545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broom, G.M.; Sha, B.-L. Cutlip and Center’s Effective Public Relations, 11th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz, D.; Hristodoulakis, I. Practitioner roles, public relations education, and professional socialization: An exploratory study. J. Public Relat. Rev. 1999, 11, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauren, M.M.; Dozier, D.M. The missing link: The public relations manager role as a mediator of organizational environments and power consequences for the function. J. Public Relat. Rev. 1992, 4, 205–220. [Google Scholar]

- Leichty, G.; Springston, J. Elaborating public relations roles. J. Mass Commun. Q. 1996, 73, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, D.; Warnaby, G.; Newman, A.J. Public relations practitioner role enactment at the senior management level within U.K. companies. J. Public Relat. Rev. 2000, 12, 227–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, D.; Newman, A.; DeSanto, B. What do communication managers do? Defining and refining the core elements of management in a public relations/corporate communication context. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2005, 82, 873–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, E.L.; Serini, S.A.; Wright, D.K.; Emig, A.G. Trends in public relations roles: 1990–1995. Public Relat. Rev. 1998, 24, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broom, G.M.; Dozier, D.M. Advancement for public relations role models. Public Relat. Rev. 1986, 12, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Hon, L.C. The influence of gender composition in powerful positions on public relations practitioners’ gender-related perceptions. J. Public Relat. Rev. 2002, 14, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cline, C.G.; Toth, E.L.; Turk, J.V.; Walters, L.M.; Johnson, N.; Smith, H. The Velvet Ghetto: The Impact of the Increasing Percentage of Women in Public Relations and Business Communication; International Association of Business Communicators Research Foundation: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Creedon, P.J. Public relations and “women’s work”: Towards a feminist analysis of public relations roles. In Public Relations Research Annual; Grunig, L.A., Grunig, J.E., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1991; pp. 67–84. [Google Scholar]

- Dozier, D.M.; Grunig, L.A.; Grunig, J.E. Manager’s Guide to Excellence in Public Relations and Communication Management; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- International Association of Business Communicators. Available online: http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m4422/is_5_19/ai_91213364/ (accessed on 30 July 2017).

- Toth, E.L.; Cline, C.G. Beyond the Velvet Ghetto; International Association of Business Communicators Research Foundation: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Toth, E.L.; Grunig, L.A. The missing story of women in public relations. J. Public Relat. Rev. 1993, 5, 153–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanc, A.; White, C. Cultural perceptions of public relations gender roles in Romania. Public Relat. Rev. 2011, 37, 103–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J. A typological study on the PR practitioners’ perception toward their job roles and functions. Korean J. Mass Commun. Q. 2002, 46, 112–249. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, I.S. AQ study of practitioner perceptions about public relations practitioner’s role and expertise for U.S.—Based multinational corporations in Korea. Presented at the Thirteenth Annual Conference of the International Society for the Scientific Study of Subjectivity, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY, USA, October 23–25 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Korean Businessman Association. The Guideline for Public Relations Practitioners: How Businessman Can Handle Mass Media? Korean Businessman Association: Seoul, Korea, 1999.

- Kim, Y.; Hon, L. Craft and professional models of public relations and their relation to job satisfaction among Korean public relations practitioners. J. Public Relat. Rev. 1998, 10, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, C.; Rossman, G.B. Designing Qualitative Research, 6th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, SA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- The Korea PR Consultancy Association. Available online: http://www.kprca.or.kr/members/members1.asp (accessed on 30 July 2017).

- Edelman Korea. Available online: http://www.edelman.co.kr/web/insight/insights_view.php?class=&uid=15 (accessed on 30 July 2017).

- Lindlof, T.R. Qualitative Communication Research Methods, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 144, 548–549. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Cultures Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind; McGraw Hill: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Jeong, J.Y. A study on the influence of the organization-public relationships on the public’s perception during an organization’s crisis situations. Korean J. Journal. Comm. Stud. 2002, 46, 588–633. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, J.Y. PR practitioner’s perceptions of their ethics in Korean global PR. Public Relat. Rev. 2011, 37, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeong, J.; Park, N. Core Elements for Organizational Sustainability in Global Markets: Korean Public Relations Practitioners’ Perceptions of Their Job Roles. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1646. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091646

Jeong J, Park N. Core Elements for Organizational Sustainability in Global Markets: Korean Public Relations Practitioners’ Perceptions of Their Job Roles. Sustainability. 2017; 9(9):1646. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091646

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeong, JiYeon, and Nohil Park. 2017. "Core Elements for Organizational Sustainability in Global Markets: Korean Public Relations Practitioners’ Perceptions of Their Job Roles" Sustainability 9, no. 9: 1646. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091646