Moral Education for Sustainable Development: Exploring Morally Challenging Business Situations within the Global Supply Chain Context

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainability Educaton in TA

2.2. Moral Responsibility Theory of Corporate Sustainability

2.3. Need for Moral Development Education for Corporate Sustainability

2.4. Kohlberg’s Moral Development Stage Theory

2.5. Research Gaps and Objectives

3. Methods

3.1. Two-Step Approach

3.2. Participants

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

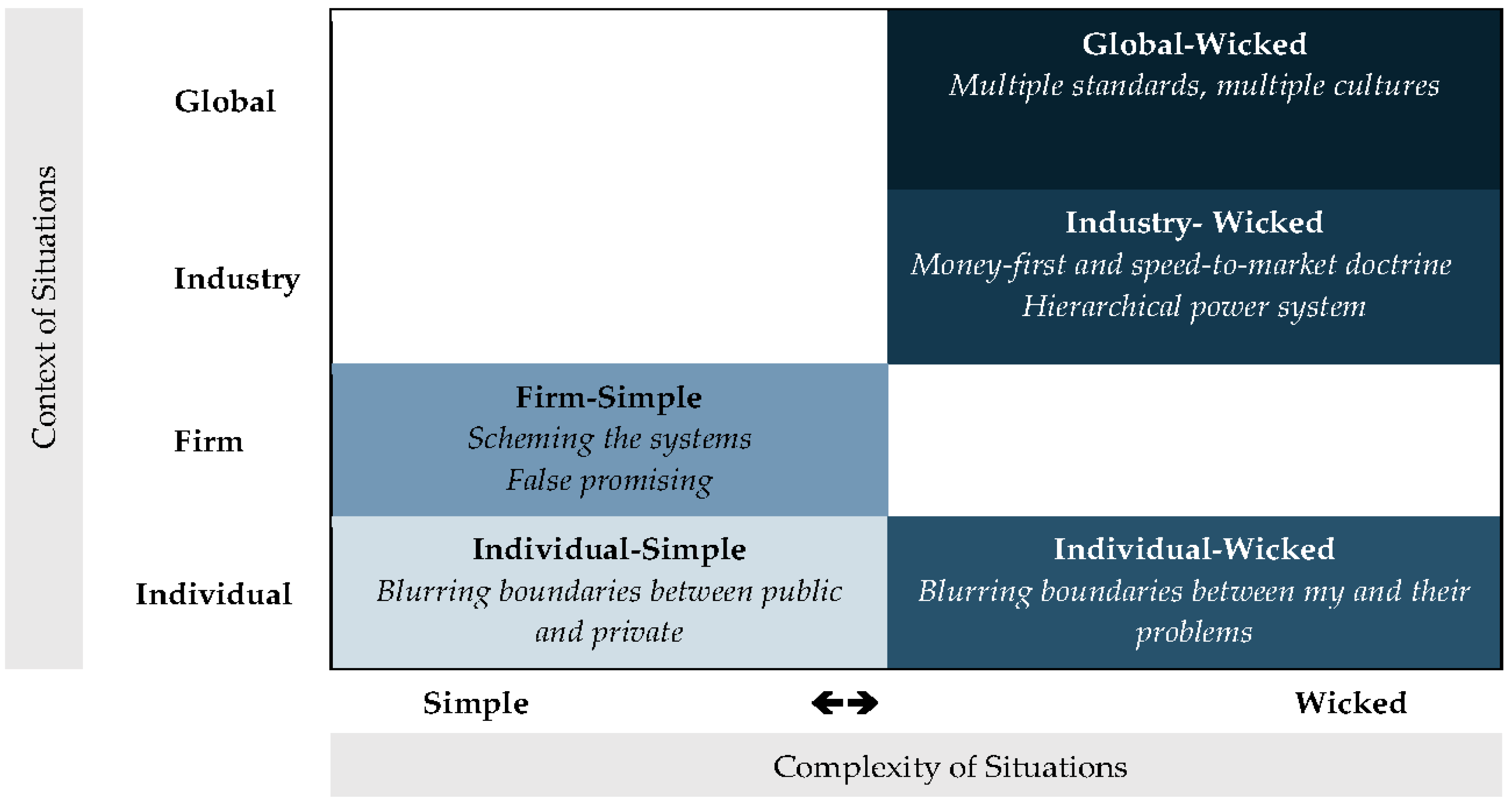

4. Interpretation

4.1. Morally Challenging Situations: Individual-Simple

I see that your scarf is a print, it could have possibly been purchased from a print studio by the scarf company and paid a very hefty price for one pattern, which would be somewhere in the neighborhood of $600. Pretty pricey, significant. At a meeting with the print artists, one of my print designers comes to me and says “Someone asked me to make a copy of this print, and I know I was not supposed to do this. What should I do?”

4.2. Morally Challenging Situations: Individual-Wicked

Rebate means an agreement, no matter how many orders I give, you have to meet the price, quality, whatever that is. But every piece I give you, you give me back 50 cents, personally. It becomes $40–50 K per year quickly. And you have to find a way to carry the cash to me because I don’t want that amount shown in my account. I was, like, why are you doing this? They [factory owners] said they have to give this to the buyer for future business. Nothing I can do.

4.3. Morally Challenging Situations: Firm-Simple

So it’s not really that my competition is cheating on this rule of origin on the yarn. It’s actually some of my potential customers playing games, like, import cheaper, way cheaper yarn and made of fabric but they still claim it’s made-in-the-U.S. yarn or made-in-the-region yarn. So that really gives all those players who wants to work by the rule, they get to really suffer because of that. In reality, they have to fight with those people who don’t play by the rules.

So, we went ahead and shipped it [to the retailer]. So, it essentially went right to their retail stores. So, we shipped it to them and we got nailed for it and so we took it all back. (…). I’m sure we still have some of it in our warehouse! It was such a large order. So, they [retailer] don’t pay for it. Then we’re stuck with all these products, and we already paid the factory (Julie).

4.4. Morally Challenging Situations: Industry-Wicked

Nike is the same way, Adidas, Nike. And I think Adidas and that group needs to make a moral decision as well because the polyester that they are using is internally getting into the food chain and I don’t know if you know, I’m sure you know a lot about that, the microfibers are breaking down and they get into the water which in turn are getting to your fish, into your food system. I think that’s a moral decision.

BCI has certified emerging countries, less developed countries whose production practices are far, far, far below ours. They use chemicals, insecticides, herbicides that are banned in the US. BCI has been going in and basically blindly certified some of these countries for small and one family operation where one person has an acre or two. They are not at the commercial scales. BCI’s message is wrong.

That’s one of the conversations I face on a daily basis with A-list customers (top buyers). Customers come in and say you got to help me, this came up and that came up. We have to have this yarn in 3 weeks or 4 weeks. Meanwhile, I’m quoting 6 weeks because I have other orders in line. In that case, you either lose that customer, or take the customer’s request and make everything bulge. And now, there is this domino effect, and if the business stays like this, it goes on eternally so there’s just no catching up. So there’s a moral decision with that.

The margin [is the key]. Sent through [issued] markdown paperwork to one of our suppliers. We charged back $5000 for a markdown which they [suppliers] didn’t agree to or will agree to. But, we just did so just to get the targeted margin for that quarter.

They [her company’s retail buyers] made them [suppliers] pay money for markdowns or those kind of things that wasn’t in the vendor’s best interest. And a lot of times I had bosses tell me to do illegal things and write chargebacks to a manufacturer that didn’t really owe me any money. I never did anything illegal, but I was asked to several times, but make the phone calls to say this is what I’m doing to you. I’m dropping your line, marking your line down, you know, those kinds of things the manufacturer didn’t want you to do but you needed to do to get your number.

But sometimes you’re the decision maker, so you are not influenced by somebody else, but some people, some companies, for example, the leader, the top executive has the mindset of “Let’s do it quickly, no matter what”. If a leader has done that, then people on a limb may think “Hey, I can do that because my leader, my boss, tells me I have to do that no matter what, then I can do under the table stuff” [referring to receiving bribes].

4.5. Morally Challenging Situations: Global-Wicked

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cambridge University Press; United Nations. Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. 1987. Available online: http://www.un-documents.net/our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2017).

- Armstrong, C.; LeHew, M.L.A. Barriers and Mechanisms for the Integration of Sustainability in Textile and Apparel Education: Stories from the Front Line. Fash. Pract. 2014, 6, 59–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicken, P. Global Shift: Mapping the Changing Contours of the World Economy, 7th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 1609180062. [Google Scholar]

- Ha-Brookshire, J.; Hawley, J. Envisioning the Clothing and Textile Discipline for the 21st Century: Discussion on its Scientific Nature and Domain. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2013, 31, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha-Brookshire, J. Toward Moral Responsibility Theories of Corporate Sustainability and Sustainable Supply Chain. J. Bus. Ethics 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, K.M. “If you tickle us...” How corporations can be moral agents without being persons. J. Value Inq. 2013, 47, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T. Nike Balks at Buying in Bangladesh Despite Margin Pressure. 2014. Available online: https://sourcingjournalonline.com/nike-balks-buying-bangladesh-despite-margin-pressure-td/ (accessed on 20 July 2017).

- Donaldson, T. H&M Plans to Buy More from Bangladesh. 2014. Available online: https://sourcingjournalonline.com/hm-plans-buy-bangladesh-td/ (accessed on 20 July 2017).

- Kenneally, I. Walmart Slammed for “Pathetic” Contribution to Rana Plaza Victims Fund: $2.2 Million. 2014. Available online: https://sourcingjournalonline.com/walmart-slammed-pathetic-contribution-rana-plaza-victims-fund-2-2-million/ (accessed on 20 July 2017).

- Barrow, H.S.; Tamblyn, R.M. Problem-Base Learning: An Approach to Medical Education; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.; Jonassen, D.H.; Liu, R. Problem-based Learning. In Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014; Volume 3, pp. 485–506. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlberg, L. A current statement on some theoretical issues. In Lawrence Kohlberg: Consensus and Controversy; Modgil, S., Modgil, C., Eds.; Falmer Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1986; pp. 485–546. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, C.; LeHew, M.L.A. Scrutinizing the Explicit, the Implicit and the Unsustainable: A Model for Holistic Transformation of a Course for Sustainability. J. Teach. Educ. Sustain. 2011, 13, 17–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leerberg, M.; Riisberg, V.; Boutrup, J. Design Responsibility and Sustainable Design as Reflective Practice: An Educational Challenge. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 18, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B.G.; LeHew, M.L.A.; Hiller Connell, K.Y.; Sutheimer, S.; Hustvedt, G. Professional Development and Education for Apparel and Textile Educators. 2016. Available online: https://athenas.ksu.edu/ (accessed on 7 July 2017).

- Dempsey, J. Corporations and Non-agential Moral Responsibility. J. Appl. Philos. 2013, 30, 334–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubbink, W. A Moral Grounding of the Duty to Further Justice in Commercial Life. Ethical Theory Moral Pract. 2015, 18, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaner, L.E. Educating for Personal and Social Responsibility: A Review of the Literature. Lib. Educ. 2005, 91, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, W.G., Jr. Forms of Ethical and Intellectual Development in the College Years: A Scheme, 1st ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1998; ISBN 0787941182. [Google Scholar]

- Passarella, E.T.; Terenzini, P.T. How College Affect Students: A Third Decade of Research; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2005; Volume 20, ISBN 0787910449. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, M.L. Empathy and Moral Development: Implications for Caring and Justice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; ISBN 052158034X. [Google Scholar]

- Noddings, N. Educating Moral People: A Caring Alternative to Character Education; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 080774168X. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory, 2nd ed.; Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Astin, A.W. What Matters in College? Four Critical Years Revisited; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lapsley, D.K. Moral Psychology; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013; ISBN 1412995302. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011; ISBN 1412974178. [Google Scholar]

- Rittel, H.W.; Webber, M.M. Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conklin, J. Dialogue Mapping: Building Shared Understanding of Wicked Problems; Wiley Publishing: Chichester, UK, 2006; ISBN 0470017686. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, L. Adidas Beats 2015 Better Cotton Target, 2016. Available online: https://sourcingjournalonline.com/adidas-beats-2015-better-cotton-target/ (accessed on 20 July 2017).

- WWD Staff, Chargebacks Crisis: Saks Inc. to Repay $21.5M to Vendors. 2005. Available online: http://wwd.com/business-news/financial/chargebacks-crisis-saks-inc-to-repay-21-5m-to-vendors-581255/ (accessed on 20 July 2017).

- Morais, T.; Silva, H.; Lopes, J.; Dominguez, G. Argumentative Skills Development in Teaching Philosophy to Secondary School Students through Constructive Controversy: An Exploratory Study Case. Curric. J. 2017, 28, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name a | Activities | Descriptions |

|---|---|---|

| Mark | Interview and Focus Group | A second generation cotton farmer with over 40 years of experience. The most difficult situation: following all current regulations and rules to continue his business in a challenging market environment. |

| James | Interview | A third-generation cotton farmer and gin owner of 40 years. The most difficult situation: major companies’ false claims about cotton and cotton industry. |

| Amanda | Interview and Focus Group | A global sourcing professional of uniform products with over 20 years of experience. The most difficult situation: not being able to keep the promises she made to her vendors. |

| Jean | Interview and Focus Group | A global sourcing professional of women’s intimate wear with over 20 years of experience. Currently residing in New York, trying to make the supply chain more sustainable. The most difficult situation: not being able to exercise her personal values in professional settings. |

| Sherry | Interview | A global sourcing professional of outdoor wear based in the Midwest with over 30 years of experience. Primarily works with vendors in China, Bangladesh, and some African countries. The most difficult situation: to watch U.S. professionals taking bribes as part of their regular income sources in developing countries. |

| Damien | Focus group | A retired executive from an accessory manufacturing company in the Southeast. The most difficult experience: false marketing claims that are out of control. |

| Sarah | Interview | A color analyst in an apparel company in the Southeast with 35 years of experience. She used to work in NYC for a large buying office. The most difficult experience: dealing with and honoring copyrights. |

| Scott | Interview | A communication specialist of 3 years in a marketing cooperative in the Midwest. The most difficult experience: being a young professional, questioning senior colleagues’ decisions and rules of negotiating with more experienced clients. |

| Derek | Interview | A VP of Sales for a yarn manufacturer with over 30 years of experience. The most difficult situation: to satisfy customers’ quick delivery requests without jeopardizing relationships on a daily basis. |

| Charles | Interview | A CEO of a yarn manufacturing mill with 50 years of experience. The most difficult situation: closing down plants and moving the facilities to another country. |

| Julie | Interview and Focus Group | A director of product development for an apparel company with 20 years of experience. The most difficult situation: not honoring contracts (e.g., shipping wrong goods to retailers) due to various circumstances. |

| Danielle | Interview | A designer for a women’s casual wear company with 15 years of experience. The most difficult situation: understanding that her work was contributing to water pollution in Bangladesh. |

| Sally | Interview | A VP of merchandising and design for a large apparel company with 30 years of experience. The most difficult situation: dealing with both factories and retailers when no one wants to compromise. |

| Sunny | Interview and Focus Group | A retired executive of a large accessory company with 40 years of experience. The most difficult situation: being threatened by retailers to issue unsubstantiated chargebacks to the vendors who had no faults. |

| Melanie | Interview | A retired executive of a large retail store chain with 40+ years of experience. The most difficult situation: dealing with “small” favors from vendors (e.g., expensive dinner, gifts, etc.). |

| Amy | Focus group | A logistics specialist for a large apparel company with 25 years of experience. The most difficult situation: colleagues used company’s resources for personal benefits (e.g., using company’s containers to import personal goods). |

| Danny | Focus group | A general manager for a uniform manufacturer with 30 years of experience. The most difficult situation: standing up for wrongdoings of his supervisor. |

| Jaime | Focus group | A retired sourcing professional with over 20 years of experience; used to work in New York City. The most difficult situation: realizing her supervisor had a mistress in Hong Kong who was supported by the company’s money. |

| Kris | Focus group | A retired executive of a large apparel brand with 40+ years of experience. The most difficult situation: copyright issues and marketing games. |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ha-Brookshire, J.; McAndrews, L.; Kim, J.; Freeman, C., Jr.; Jin, B.; Norum, P.; LeHew, M.L.A.; Karpova, E.; Hassall, L.; Marcketti, S. Moral Education for Sustainable Development: Exploring Morally Challenging Business Situations within the Global Supply Chain Context. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1641. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091641

Ha-Brookshire J, McAndrews L, Kim J, Freeman C Jr., Jin B, Norum P, LeHew MLA, Karpova E, Hassall L, Marcketti S. Moral Education for Sustainable Development: Exploring Morally Challenging Business Situations within the Global Supply Chain Context. Sustainability. 2017; 9(9):1641. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091641

Chicago/Turabian StyleHa-Brookshire, Jung, Laura McAndrews, Jooyoun Kim, Charles Freeman, Jr., Byoungho Jin, Pamela Norum, Melody L. A. LeHew, Elena Karpova, Lesya Hassall, and Sara Marcketti. 2017. "Moral Education for Sustainable Development: Exploring Morally Challenging Business Situations within the Global Supply Chain Context" Sustainability 9, no. 9: 1641. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091641