Aesthetic and Spiritual Ecosystem Services Provided by Urban Sacred Sites

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Study Area

3. Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Statistical Analyses

4. Results

4.1. Congregants’ Use of and Sentiments towards Urban Sacred Spaces

4.2. Appreciation of Urban Sacred Spaces by Congregants

4.3. Contributions to Spiritual, Cultural and Aesthetic Experience

4.4. Perceived Social, Ecological and Economic Benefits from Urban Sacred Places

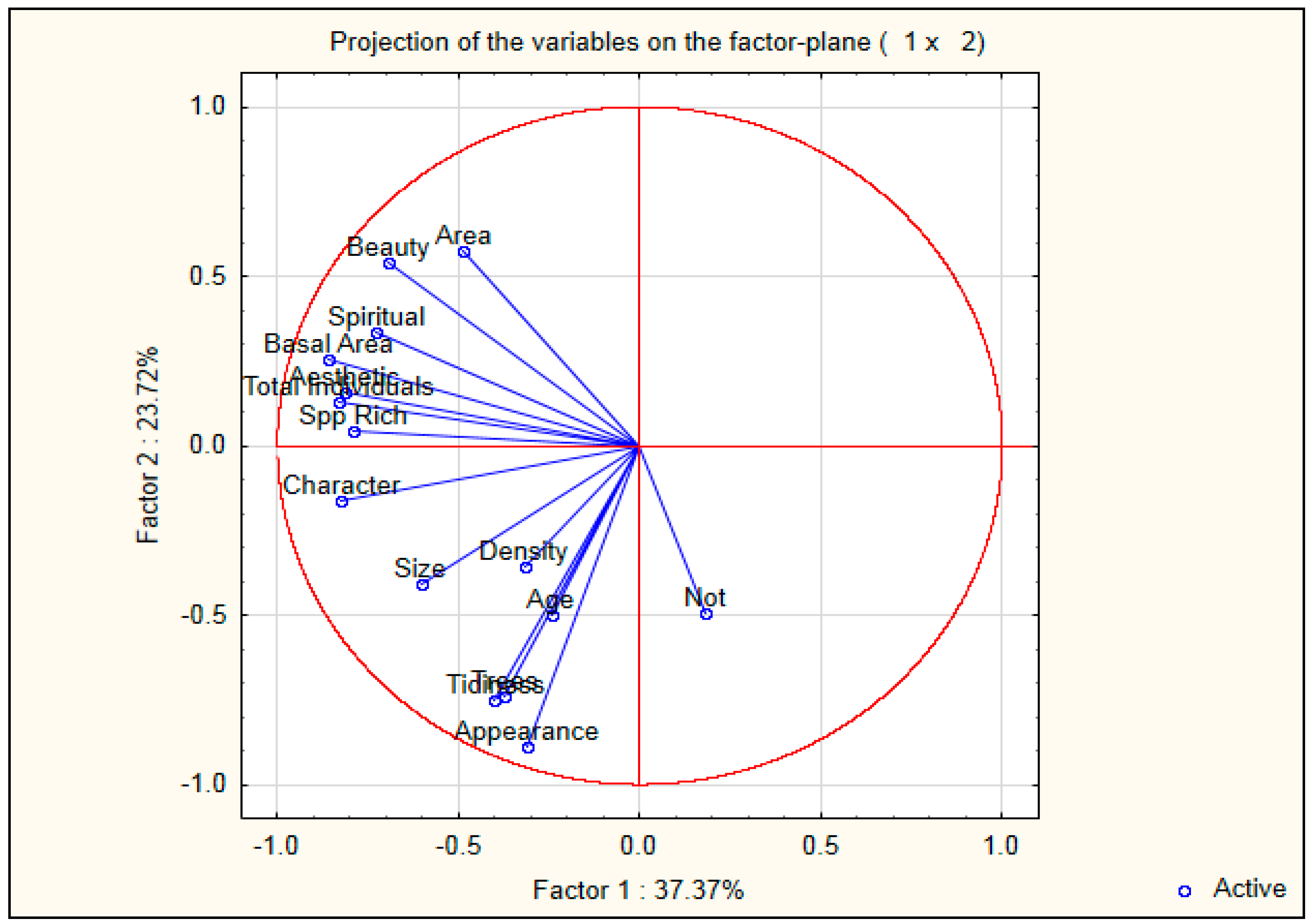

4.5. The Effect of Garden Attributes on User Perceptions

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; 155p. [Google Scholar]

- Convention on Biological Diversity Secretariat. Cities and Biodiversity Outlook: Action and Policy—A Global Assessment of the Links between Urbanization Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; CBD: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2012; 64p. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Barton, D.N. Classifying and valuing ecosystem services for urban planning. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 86, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livesley, S.J.; McPherson, G.M.; Calfapietra, C. The urban forest and ecosystem services: Impacts on urban water, heat, and pollution cycles at the tree, street, and city scale. J. Environ. Qual. 2016, 45, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickett, S.T.A.; Boone, C.G.; McGrath, B.P.; Cadenasso, M.L.; Childers, D.L.; Ogden, L.A.; McHale, M.; Grove, M.J. Ecological science and transformation to the sustainable city. Cities 2013, 32, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindley, S.; Pauleit, S.; Yeshitela, K.; Cilliers, S.; Shackleton, C. Rethinking urban ecosystem services and green infrastructure from the perspective of African cities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Tian, H.; Pan, S.; Liu, M.; Lockaby, G.; Schilling, E.B.; Stanturf, J. The effects of forest regrowth and urbanization on ecosystem carbon storage in a rural–Urban gradient in the southeastern United States. Ecosystems 2008, 11, 1211–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.C.; Maheswaran, R. The health benefits of urban green spaces: A review of the evidence. J. Public Health 2011, 33, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shackleton, C.M.; Blair, A. The abundance of urban public green space influences residents’ perceptions, uses and willingness to get involved in two small towns in South Africa. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 113, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Mitchell, R.; De Vries, S.; Frumkin, H. Nature and health. Ann. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Berg, A.E.; Maas, J.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P. Green space as a buffer between stressful life events and health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akpinar, A. How is quality of urban green spaces associated with physical activity and health? Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 16, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macintyre, S.; Ellaway, A.; Hiscock, R.; Kearns, A.; Der, G.; McKay, L. What features of the home and the area might help to explain observed relationships between housing tenure and health? Evidence from the west of Scotland. Health Place 2003, 9, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, W.C.; Kuo, F.E.; Depooter, S.F. The fruit of urban nature: Vital neighbourhood spaces. Environ. Behav. 2004, 36, 678–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemperman, A.; Timmermans, H. Green spaces in the direct living environment and social contacts of the aging population. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 129, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takano, T.; Nakamura, K.; Watanabe, M. Urban residential environments and senior citizens’ longevity in megacity areas: The importance of walkable green spaces. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2002, 56, 913–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, C.D.; Parker, C.M.; Shackleton, C.M. The use and appreciation of urban green spaces: The case of selected botanical gardens in South Africa. Urban For. Urban Green. 2010, 9, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tyrväinen, L.; Väänänen, H. Benefits and uses of urban forests and trees. In Urban Forests and Trees—A Reference Book; Konijnendijk, C.C., Nilsson, K., Randrup, T.B., Schipperijn, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2005; pp. 81–114. [Google Scholar]

- Keniger, L.E.; Gaston, K.J.; Irvine, K.N.; Fuller, R.A. What are the benefits of interacting with nature? Int. J. Environ. Res. Publc Health 2013, 10, 213–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byers, B.A.; Cunliffe, R.N.; Hudak, A.T. Linking the conservation of culture and nature: A case study of sacred forests in Zimbabwe. Hum. Ecol. 2001, 29, 187–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deil, U.; Culmsee, H.; Berriane, M. Sacred groves in Morocco: A society’s conservation of nature for spiritual reasons. Silva Carel 2005, 49, 185–201. [Google Scholar]

- De Lacy, P.; Shackleton, C.M. Woody plant species richness, composition and structure in urban sacred sites, Grahamstown, South Africa. Urban Ecosyst. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.L.; Khumbongmayum, A.D.; Tripathi, R.S. The sacred groves and their significance in conserving biodiversity an overview. Int. J. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2008, 34, 277–291. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.L.; Menon, S.; Bawa, K.S. Effectiveness of the protected area network in biodiversity conservation, a case study of Meghalaya, India. Biodivers. Conserv. 1997, 6, 853–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frosch, B. Characteristics of the vegetation of tree stands on sacred sites in comparison to well preserved forests in northwestern Morocco. Ecol. Mediterr. 2010, 36, 83–95. [Google Scholar]

- Gokhale, Y; Pala, N.A. Ecosystem services in sacred natural sites (SNSs) of Uttarakhand: A preliminary survey. J. Biodivers. 2011, 2, 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- McBarron, E.J.; Benson, D.H.; Doherty, M.D. The botany of old cemeteries. Cunninghamia 1988, 2, 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Gilfedder, L. Threatened species from Tasmania’s remnant grasslands. Tasmanian For. 1990, 2, 129–132. [Google Scholar]

- Betz, R.F.; Lamp, H.F. Species composition of old settler savannah and sand prairie cemeteries in northern Illinois and northwestern Indiana. In Proceedings of the Twelfth North American Prairie Conference, University of Northern Iowa, Cedar Falls, IA, USA, 6–9 August 1992; Smith, D.A., Jacobs, C.A., Eds.; pp. 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Orstan, A.; Kosemen, M. Graves and snails: Biodiversity conservation in an old cemetery in Istanbul, Turkey. Triton 2009, 19, 40–41. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, G.W.; Barrett, T.L. Cemeteries as repositories of natural and cultural diversity. Conserv. Biol. 2001, 15, 1820–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salick, J.; Amend, A.; Anderson, D.; Hoffmeister, K.; Gunn, B.; Zhendong, F. Tibetan sacred sites conserve old growth trees and cover in the eastern Himalayas. Biodivers. Conserv. 2007, 16, 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, H.T.; Manabe, T.; Ito, K.; Fujita, N.; Imanishi, A.; Daisuke, H.; Iwasaki, A. Integrating ecological and cultural values toward conservation and utilisation of shrine/temple forests as urban green space in Japanese cities. Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 2010, 6, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, N.S. The history of English churchyard landscapes illustrated by Rivenhall, Essex. In Sacred Species and Sites: Advances in Biocultural Conservation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, N.S. Wildlife conservation in churchyards: A case-study in ethical judgements. Biodivers Conserv. 1995, 4, 916–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrakanth, M.G.; Gilless, J.K.; Gowramma, V.; Nagaraja, M.G. Temple forests in India’s forest development. Agrofor. Syst. 1990, 11, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keswani, K. The practice of tree worship and the territorial production of urban space in the Indian neighbourhood. J. Urban Des. 2017, 22, 370–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafni, A. Rituals, Ceremonies and Customs Related to Sacred Trees with a Special Reference to the Middle East. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2007, 3, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, D.M.; Salick, J.; Noseley, R.K.; Xiaokun, O. Conserving the sacred medicine mountains: A vegetation analysis of Tibetan sacred sites in Northwest Yunnan. Biodivers. Conserv. 2005, 14, 3065–3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, N.; Higgins-Zogib, L.I.Z.; Mansourian, S. The links between protected areas, faiths, and sacred natural sites. Conserv. Biol. 2009, 23, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhagwat, S.A.; Ormsby, A.A.; Rutte, C. The role of religion in linking conservation and development: Challenges and opportunities. J. Study Rel. Nat. Cult. 2011, 5, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awoyemi, S.M.; Gambrill, A.; Ormsby, A.; Vyas, D. Global efforts to bridge religion and conservation: Are they really working? In Topics in Conservation Biology; Povilitis, T., Ed.; Intech: Vienna, Austria, 2012; pp. 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Mucina, L.; Rutherford, M.C. (Eds.) The Vegetation of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland. Strelitzia 19; South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI): Pretoria, South Africa, 2006; p. 816.

- Integrated Development Plan. Makana Local Municipality. 2011. Available online: http://goo.gl/dGSkhp (accessed on 2 September 2014).

- McConnachie, M.M.; Shackleton, C.M.; McGregor, G. Extent of public green space and alien species in ten small towns in the thicket biome, South Africa. Urban For. Urban Green. 2008, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer-Oatey, H. Culturally Speaking: Culture, Communication and Politeness Theory, 2nd ed.; Continuum: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Downs, R.M.; Stea, D. Maps in Minds: Reflections on Cognitive Mapping; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1977; pp. 264–276. [Google Scholar]

- Chinyimba, A. An assessment of Urban Residents’ Knowledge and Appreciation of the Intangible Benefits of Trees in Two Medium Sized Towns in South Africa. Master’s Thesis, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia: The Human Bond with Other Species; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, P.H.; Kellert, S.R. (Eds.) Children and Nature: Psychological, Sociocultural, and Evolutionary Investigations; Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R. The nature of the view from home: Psychological benefit. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 507–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldridge, J.; Sempik, J. Social and Therapeutic Horticulture: Evidence and Messages from Research; Evidence Issue 6; CCFR Loughborough University: Loughborough, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jackle, H.; Rudner, M.; Deil, U. Density, spatial pattern and relief features of sacred sites in northern Morocco. Landsc. Online 2013, 32, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Grant, M. Biodiversity and human health: What role for nature in healthy urban planning? Built Environ. 2005, 31, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, E.S.; Swasey, J.E. Perceived stress reduction in urban public gardens. HortTechnology 1996, 6, 125–128. [Google Scholar]

- Chiesura, A. The role of urban parks for the sustainable city. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 68, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafortezza, R.; Carrus, G.; Sanesi, G.; Davies, C. Benefits and well-being perceived by people visiting green spaces in periods of heat stress. Urban For. Urban Green. 2009, 8, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, R.; McLeod, C.; Valentine, P. (Eds.) Sacred Natural Sites: Guidelines for Protected area Managers; (No. 16); IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Catharine Ward Thompson. Urban Open Space in the 21st Century. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2002, 60, 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Özgüner, H.; Kendle, A.D. Public attitudes towards naturalistic versus designed landscapes in the city of Sheffield (UK). Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 74, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, H.; Hitchmough, J.; Jorgensen, A. All about the ‘wow factor’? The relationships between aesthetics, restorative effect and perceived biodiversity in designed urban planting. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 164, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, R.A.; Irvine, K.N.; Devine-Wright, P.; Warren, P.H.; Gaston, K.J. Psychological benefits of green space increase with biodiversity. Biol. Lett. 2007, 3, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowarik, I. Novel urban ecosystems, biodiversity, and conservation. Environ. Pollut. 2011, 159, 1974–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordh, H.; Hartig, T.; Hagerhall, C.M.; Fry, G. Components of small urban parks that predict the possibility for restoration. Urban For. Urban Green. 2009, 8, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flouri, E.; Midouhas, E.; Joshi, H. The role of urban neighbourhood green space in children’s emotional and behavioural resilience. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milton, K. Nature is already sacred. Environ. Var. 1999, 8, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J.; Adams, B.; Berkes, F.; de Athayde, S.F.; Dudley, N.; Hunn, E.; Maffi, L.; Milton, K.; Rapport, D.; Robbins, P.; et al. The intersections of biological diversity and cultural diversity: Towards integration. Conserv. Soc. 2009, 7, 100–112. [Google Scholar]

- Ormsby, A.A. Analysis of local attitudes toward sacred groves of Meghalaya and Karnataka, India. Conserv. Soc. 2013, 11, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, J. The purest of human pleasures: The characteristics and motivations of garden visitors in Great Britain. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| A Church Garden is Necessary Because | Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G | NG | G | NG | G | NG | G | NG | G | NG | |

| It reminds me of the beauty created by God | 61 | 48 | 27 | 32 | 12 | 18 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| It adds character to the site | 53 | 30 | 36 | 50 | 10 | 13 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 2 |

| It signifies tranquillity and peace | 63 | 35 | 32 | 53 | 5 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| It enhances ones religious experience | 27 | 10 | 29 | 33 | 32 | 35 | 9 | 17 | 3 | 5 |

| It promotes remembrance of departed ones | 17 | 5 | 17 | 23 | 40 | 52 | 20 | 20 | 5 | 0 |

| It provides reflection space | 39 | 18 | 42 | 70 | 15 | 12 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| It is not necessary at all | 1 | 0 | 5 | 18 | 17 | 35 | 23 | 30 | 53 | 17 |

| Garden Attribute | Aesthetic | Cultural | Spiritual |

|---|---|---|---|

| A garden view would greatly improve my aesthetic, cultural or spiritual experience | 68 | 35 | 54 |

| My aesthetic, cultural or spiritual experience would improve if the garden were larger | 36 | 4 | 18 |

| My aesthetic, cultural or spiritual experience would improve if the garden have a greater variety of plants | 42 | 12 | 18 |

| My aesthetic, cultural or spiritual experience would improve if it had specific tree species or amenities | 32 | 12 | 14 |

| Benefits | Provided (%) | Not Previously, Considered (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G | NG | G | NG | ||

| Social | • As a place to meet that promotes social interaction among congregants | 71 | 83 | 29 | 17 |

| • Improve an individual’s mood and relieves stress | 70 | 70 | 30 | 30 | |

| • Improve the aesthetic beauty of the religious area | 72 | 80 | 28 | 20 | |

| • Offer cultural, spiritual and aesthetic fulfilment | 57 | 50 | 44 | 50 | |

| Ecological | • Remove pollutants from the air | 63 | 73 | 37 | 27 |

| • Provide a home for birds, insects and small animals | 79 | 80 | 21 | 20 | |

| • Help to reduce excessive water loss and run-off from concrete areas and protect soils from erosion | 55 | 67 | 45 | 33 | |

| • Purify air and water of an area | 58 | 60 | 42 | 40 | |

| • Reduce temperatures by providing shade (regulate micro-climate) | 73 | 77 | 27 | 23 | |

| • Help reduce the noise levels | 50 | 43 | 50 | 58 | |

| • Mitigation of climate change | 38 | 63 | 62 | 38 | |

| • Diminish the intensity/force of strong winds | 45 | 43 | 55 | 37 | |

| Economic | • Increase house or rent price of houses near the area | 29 | 30 | 71 | 70 |

| • Make the area (and town) a tourist attraction, resulting in employment and revenues | 37 | 53 | 63 | 48 | |

| • Reduce energy use (air conditioners, etc.) through regulation of the micro-climate | 25 | 43 | 75 | 58 | |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Lacy, P.; Shackleton, C. Aesthetic and Spiritual Ecosystem Services Provided by Urban Sacred Sites. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1628. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091628

De Lacy P, Shackleton C. Aesthetic and Spiritual Ecosystem Services Provided by Urban Sacred Sites. Sustainability. 2017; 9(9):1628. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091628

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Lacy, Peter, and Charlie Shackleton. 2017. "Aesthetic and Spiritual Ecosystem Services Provided by Urban Sacred Sites" Sustainability 9, no. 9: 1628. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091628